Sonneberg district

| coat of arms | Germany map |

|---|---|

|

Coordinates: 50 ° 25 ' N , 11 ° 8' E |

| Basic data | |

| State : | Thuringia |

| Administrative headquarters : | Sonneberg |

| Area : | 433.61 km 2 |

| Residents: | 57,717 (Dec. 31, 2019) |

| Population density : | 133 inhabitants per km 2 |

| License plate : | SON, NH |

| Circle key : | 16 0 72 |

| NUTS : | DEG0H |

| Circle structure: | 8 municipalities |

| Address of the district administration: |

Bahnhofstrasse 66 96515 Sonneberg |

| Website : | |

| District Administrator : | Hans-Peter Schmitz (independent) |

| Location of the district of Sonneberg in Thuringia | |

The district Sonnenberg is a district in the Franconian dominated south of the Free State of Thuringia . It is the smallest district in the Free State of Thuringia in terms of both area and population. Neighboring districts in the Sonneberger Oberland to the north and northeast are the districts of Saalfeld-Rudolstadt and Kronach , in the Sonneberger Unterland the districts of Kronach and Coburg and in the Sonneberg hinterland the districts of Coburg and Hildburghausen . In terms of spatial planning , the district belongs to the Southwest Thuringia planning region and is a member of the Southwest Thuringia planning community . On December 12, 2013, the district council of the district of Sonneberg voted unanimously for the application for admission to the metropolitan region of Nuremberg (in April 2014 the council of the metropolitan region in Bamberg decided on admission). On April 2, 2014, the association assembly of the metropolitan region voted unanimously for the district of Sonneberg to join.

geography

The district of Sonneberg is divided into different landscapes:

- the Oberland with the Thuringian Slate Mountains in the north and the Franconian Forest in the northeast,

- the Unterland with the Upper Main Hills in the southeast and south,

- the hinterland with the Schalkau plateau in the west.

history

Early and High Middle Ages

In its current extent, the district of Sonneberg includes territories whose historical development took place over centuries in different states. The largest part is occupied by areas that emerged from the former principality of Saxony-Coburg . During the early Middle Ages in the area around Coburg and Sonneberg there were not only larger imperial estates complexes , which were included in the form of the Radaha royal court (today Bad Rodach, Coburg district), but also larger allodial lords of the Counts of Schweinfurt and the Counts of Sterker-Wohlsbach . Until the late Middle Ages, the southeastern part of the district was still under the influence of the Bamberg diocese . In 1012 the remnants of the imperial property around Saalfeld and Coburg came into the hands of Count Palatine Ezzo of Lorraine , whose daughter, the Polish Queen Richeza , bequeathed these areas to Archbishop Anno of Cologne in 1056 . After Richeza's death in 1069, Anno founded a Benedictine monastery in Saalfeld , which he equipped with the Ezzonian possessions around Saalfeld and Coburg.

Territory formation

On the southern edge of the Thuringian Slate Mountains, the noble lords of Sonneberg and von Schaumberg established their own lords . The Lords of Sonneberg were ministerials from the Dukes of Andechs-Meranien . At the beginning of the 13th century several members of this sex were mentioned; an indication that the family named themselves after their newly built castle Sonneberg . The acquisition of larger estates around Sonneberg from the Benedictine monastery Saalfeld (1252) and the establishment of the Cistercian monastery Sonnefeld near Coburg by Heinrich von Sonneberg mark the high point in the history of the family. During the second half of the 13th century, the family began to decline economically, which died out in the male line after 1310.

The origin of the Messrs. Von Schaumberg is uncertain. Possibly it was a question of noble freemen, who, however, were in a ministerial relationship with the Counts of Sterker-Wohlsbach around 1200 and who followed them in the possession of Schaumberg Castle . In 1216 they first called themselves "von Schaumberg" after their newly acquired castle. The possessions of the Lords of Schaumberg comprised imperial fiefs that reached from Schalkau to Rennsteig . After the Lords of Sonneberg, who were related to them, died out in 1310, they expanded their possessions to include Sonneberg Castle and the surrounding properties.

The formation of territories in the Coburg-Sonneberg area began under Count Hermann I von Henneberg , who, after the Dukes of Andechs-Meranien died out in 1248, in the power vacuum that had arisen, began to build up regional rule around the center of Coburg. After the rule of Coburg had come to the Margraves of Brandenburg in the meantime , Berthold VII. (The great) of Henneberg-Schleusingen succeeded in reacquiring this "new rule" in 1315. Berthold was the new strong man in the region, to whom the nobility resident in the country also submitted. In 1315 the lords of Schaumberg gave their castles Schaumberg, Sonneberg and Neuhaus Berthold to fiefdoms. Sonneberg was completely sold to the Henneberger in the following decades. In 1317 - and after his death in 1340 his son Heinrich - Berthold had property registers ( Urbare ) drawn up of his new estates .

The rule or care of Coburg , as this area was also called, did not remain in the hands of Henneberg for long. After the death of Heinrich in 1347 and his wife Jutta in 1353, rule came to the Wettin margraves of Meissen (later also dukes) and the Electorate of Saxony . After 1353, Margrave Friedrich the Strict also succeeded in acquiring Schaumberg Castle and half of the Schalkau court from the Lords of Schaumberg. The von Schaumbergs could only claim the remains of their imperial fiefs around Rauenstein Castle, built in 1349, as an independent court and half of the Schalkau office.

Once at between Neustadt located and Sonnenberg burned bridge has long bridge court was held, Sonnenberg was since the mid-14th century part of the centering Neustadt , within it formed its own Supreme Court. The center of Neustadt, on the other hand, had been part of the Coburg office since the 14th century, which also included half of the office in Schalkau and the Neuhaus court, which was created before 1355. In 1534, a Sonneberg office was founded - mainly because of the large, lordly forest forests - which, however, was reintegrated into the Coburg office as early as 1572. In 1669 the two courts of Sonneberg and Neustadt were spun off from the Coburg office and merged into one Neustadt office. Neuhaus became an independent office in 1611.

Early modern age

The care of Coburg was part of the Wettin state and came after the "Leipzig division" in 1485 to the Ernestine line of this house. After Coburg had already been an Ernestine secondary school between 1542 and 1553 under Duke Johann Ernst of Saxony , this territory was separated from the entire Ernestine state in 1572, and a principality of Saxony-Coburg was created, which was ruled jointly by the Dukes Johann Casimir and Johann Ernst . In 1596 both divided this principality into Saxe-Coburg and Saxe-Eisenach . After the death of Johann Casimir in 1633 briefly reunited under Johann Ernst, after his death in 1638 it was transferred to Saxe-Altenburg and in 1672 to Saxe-Gotha . In the course of the "Gotha partition" in 1680, another principality of Saxe-Coburg emerged under Duke Albrecht , although it was considerably smaller than its predecessor.

Half of the office of Schalkau was added to the newly created principality of Saxony-Hildburghausen in 1680 . In 1699 Albrecht von Sachsen-Coburg died without an heir, and protracted inheritance disputes ensued, which were only ended in 1735/1742. Sachsen-Meiningen had already acquired the Saxon half of the Schalkau office in 1723, the Schaumberg half of this office in 1729 and the Schaumberg judicial district of Rauenstein in 1732 . In 1735 Sachsen-Meiningen was also awarded the Sonneberg court and the Neuhaus office. Further claims by the Meininger to the entire Neustadt office, to which the Sonneberg court had belonged up to then, were rejected in 1742 after an attempt to occupy Neustadt militarily had failed. In 1742, the Sonneberg court was transformed into a Sonneberg office, which, together with the offices of Schalkau and Neuhaus and the Rauenstein court, formed an area that was spatially separated from the core area of Saxony-Meiningen around the residential town of Meiningen , for which the name Meininger Oberland became naturalized.

Modern times

In 1770 the offices of Sonneberg, Schalkau and Neuhaus as well as the Rauenstein court were subordinated to a senior bailiff, but remained independent. The Rauenstein court was merged with the Schalkau office in 1808. After the "Gothaischen inheritance" in 1826 the villages Mupperg , Mogger , Oerlsdorf , Liebau , Lindenberg and Rotheul , which until then belonged to Saxe-Coburg, were affiliated to the office of Sonneberg. With the administrative reform in Sachsen-Meiningen in 1829, the existing offices were dissolved and merged into an administrative office in Sonneberg. With the formation of districts in Sachsen-Meiningen in 1869, the Sonneberg district emerged from the administrative office. The district was expanded in 1900 through the assignment of the village of Ernstthal , which until then had belonged to the Saalfeld district. For the district area around the former city of Sonneberg, sometimes extending beyond the district boundary, the terms Unterland in the south and southeast, Oberland in the north and northeast and Hinterland in the west were introduced.

Saalfeld areas

The villages in the northern part of the district had developed a little differently. The villages of Hasenthal , Hohenofen , Spechtsbrunn and Ernstthal originally belonged to the territory of the Gräfenthal rule . Originally part of the Orlagau , this area was still in the High Middle Ages within the dominion of the Benedictine monastery Saalfeld. Starting from Lauenstein Castle in today's Kronach district , however, they began as early as 11/12. Century the Lords of Koenitz with the establishment of a state rule. In 1250 they were followed by the Counts of Orlamünde in possession of the castle. In the middle of the 13th century, the Orlamünder had already largely driven the monastery out of the possession of the Lauenstein rulership. In 1414 they divided their territory into the dominions of Lauenstein, Lichtenberg (district of Kronach) and Graefenthal ( district of Saalfeld-Rudolstadt ). The area around Hasenthal and Spechtsbrunn came under the rule of Gräfenthal. Increasing economic decline forced the Orlamünder 1394 Gräfenthal Castle with all associated places and rights to the Wettin fiefs and finally sold in 1426 to Duke Friedrich I of Saxony . In 1438 the Wettins sold this new acquisition to the Reichserbmarschalls von Pappenheim without giving up their feudal sovereignty. It was not until 1621 that the Gräfenthal rule fell back to Sachsen-Altenburg and in 1672 it came to Gotha. With the "Gothaische Teilung" a principality of Saxony-Saalfeld was created , which came to Saxony-Coburg in 1735, but was only united with this state under constitutional law in 1805. Through the "Gothaische inheritance" also the former principality of Saxony-Saalfeld fell to Saxony-Meiningen. The Gräfenthal office, which had existed since the 17th century, became an administrative office in 1829 and was added to the Saalfeld district in 1868.

Schwarzburger areas

The villages of Neuhaus am Rennweg, Scheibe-Alsbach and Goldisthal were in the territory of the Principality of Schwarzburg . The Counts of Käfernburg-Schwarzburg had extended their domain into the upper Schwarzatal during the 11th century and were owned by the Schwarzburg (district of Saalfeld-Rudolstadt) in 1123. After the contract of Stadtilm (1599) and the final separation of the house of Schwarzburg into a line between Schwarzburg-Sondershausen and Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt , the upper Schwarzatal fell to Rudolstadt. The ridge area of the slate mountains originally belonged to the Schwarzburg office, whose official seat was moved to Königsee in 1668 ; In 1868 a district administration office in Königsee was established , to which the villages in the ridge area of the slate mountains belonged.

Latest time

While after the reorganization of the Thuringian districts on October 1, 1922, the Sonneberg district remained in existence due to a guarantee of existence, the Königsee district was dissolved and incorporated into the Rudolstadt district. The municipality of Hohenofen, which was formerly part of the Saalfeld district, was incorporated into Haselbach and thus incorporated into the Sonneberg district. On April 1, 1923, the villages of Neuhaus am Rennweg and Schmalenbuche were combined with the neighboring Hedgehog - formerly belonging to Sachsen-Meiningen - to Neuhaus am Rennweg-Igelshieb (from 1933 town of Neuhaus am Rennweg ) and also incorporated into the Sonneberg district.

The district reform of July 1, 1950 brought further changes, in which the villages of Hasenthal and Spechtsbrunn , which had previously belonged to the district of Saalfeld , were incorporated into the district of Sonneberg. With the formation of the district of Suhl , the district of Neuhaus am Rennweg was created on July 25, 1952 , which was formed from parts of the districts of Sonneberg, Saalfeld and Rudolstadt. Spechtsbrunn, Lauscha, Ernstthal, Neuhaus am Rennweg, Steinheid and Siegmundsburg were assigned to the new district by the district of Sonneberg. After the district reform in Thuringia in 1994, the districts of Sonneberg and Neuhaus am Rennweg were dissolved and a new district of Sonneberg was formed, which was made up of the old district of Sonneberg and parts of the Neuhaus district. In addition to the villages that were annexed by Sonneberg to the Neuhaus district in 1952, Scheibe-Alsbach and Goldisthal, which had belonged to the Rudolstadt district before 1952, also became part of the Sonneberg district.

In the run-up to a planned second district reform in Thuringia , a commission of experts proposed in January 2013 to merge the district with the Hildburghausen district , the city of Suhl and parts of the Schmalkalden-Meiningen district to form a large district. In protest against these plans, District Administrator Christine Zitzmann brought up a change of the district, which has been a member of the European metropolitan region of Nuremberg since October 2013 , to Bavaria.

In the legislative period from 2014 onwards, the regional reform of Thuringia in 2018 and 2019 with the coalition agreement was set as a goal to be pursued by the state government. After the preliminary law for functional and territorial reform was passed by the state parliament in June 2016, the interior minister presented the government proposal on October 11, 2016 for the reorganization of the districts and independent cities, which would allow the districts of Sonneberg, Hildburghausen and Schmalkalden-Meiningen to merge with independent city of Suhl. In the district, especially in the district town of Sonneberg, voices for a change of country to Bavaria were again loud. In Sonneberg, therefore, on May 8 and May 15, 2017, more than 3,000 demonstrators protested against the planned regional reform. The demonstrating Sonneberg city and district administrators received on-site support from the entire city council of the neighboring town of Neustadt in Upper Franconia . Further proposals for district mergers followed, but the territorial reform failed in November 2017.

Following the conclusion of the integration contracts between the communities of Lichte and Piesau, which originally belonged to the Saalfeld-Rudolstadt district, with the city of Neuhaus am Rennweg, the Sonneberg district was expanded to include these two places on January 1, 2019.

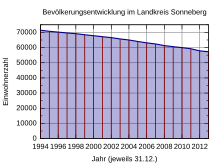

Population development

Development of the population:

|

|

|

|

|

|

politics

On September 23, 2008, the district received the title “ Place of Diversity ” awarded by the federal government .

District council

The 40 seats in the district council have been distributed among the individual parties as follows after the previous local elections since 1994:

| Political party | 1994 | 1999 | 2004 | 2009 | 2014 | 2019 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | |

| CDU | 32.1 | 14th | 36.5 | 15th | 43.6 | 18th | 40.2 | 16 | 42.3 | 17th | 37.3 | 15th |

| AfD | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 24.0 | 10 |

| The left 1 | 16.3 | 7th | 20.9 | 8th | 28.6 | 12 | 29.3 | 12 | 28.1 | 11 | 19.9 | 8th |

| SPD | 34.3 | 15th | 24.3 | 10 | 19.2 | 8th | 15.4 | 6th | 12.6 | 5 | 8.7 | 3 |

| FDP | 9.4 | 4th | 8.2 | 3 | 6.1 | 2 | 8.6 | 3 | 4.4 | 2 | 4.6 | 2 |

| GREEN 2 | 3.5 | 0 | 1.3 | 0 | 2.5 | 0 | 2.4 | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 4.1 | 2 |

| NPD | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4.1 | 2 | 4.9 | 2 | 1.4 | 0 |

| FW-SON 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4.7 | 2 | - | - |

| UNTIL 4 | - | - | 8.9 | 4th | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| DSU | 3.2 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| FORUM | 1.4 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| total | 100 | 40 | 100 | 40 | 100 | 40 | 100 | 40 | 100 | 40 | 100 | 40 |

| voter turnout | 75.2% | 58.7% | 48.4% | 50.5% | 47.2% | 56.1% | ||||||

District Administrator

Hans-Peter Schmitz (non-party) has been the district administrator of the Sonneberg district since 2018 . He replaced the district administrator Christine Zitzmann , who had been in office since 2006 and who had no longer stood as a candidate.

Former district administrators

Since the founding of the district of Sonneberg, the district had a number of district administrators, whose functional titles and electoral institutions, however, differed over time. The following people have been district administrators since the district was founded:

District executive , from 1872 ducal district administrator ; appointed by the Ministry of State:

- 1868–1874: Rudolf von Ziller

- 1874–1878: Gustav Julius Berlet

- 1878–1890: Karl Baumbach

- 1890–1901: Hermann Götting

- 1901–1912: Karl Marr

- 1913–1922: Arnold Creutzburg

District director or district administrator ; used by the country:

- 1922–1924: Karl Knauer

- 1925–1945: Max Hartung

- 1945–1948: Hans Weinland

District administrator ; Election from the district council:

- 1948–1950: Theo Gundermann (SED)

- 1950–1951: Rudolf Rost (SED)

- 1951–1952: Olga Brückner (SED)

For the period between 1952 and 1994 see Chairwoman of the Council of the District of Sonneberg .

District administrator ; direct choice:

- 1994–2006: Reiner Stuhlmann (supported by SPD)

- 2006–2018: Christine Zitzmann (CDU, later independent)

partnership

A district partnership with the Eifelkreis Bitburg-Prüm has existed since 1990 . A district partnership with the Polish district of Ostrow has existed since 2010 .

coat of arms

The district has had this four-part coat of arms since October 3, 1990.

|

|

|

|

An overview of the coats of arms of the towns and municipalities in the district can be found in the list of coats of arms in the Sonneberg district .

Economy and Infrastructure

In the Future Atlas 2016 , the Sonneberg district was ranked 341 out of 402 districts, municipal associations and independent cities in Germany, making it one of the regions with “future risks”.

Agriculture

Due to the not particularly favorable agro-ecological situation (poorly productive soils, climatic situation in the low mountain range), the region was largely settled only during the high medieval development of the country , the areas in the Thuringian Slate Mountains only in the modern era. During the late Middle Ages , a small and medium-sized peasant structure had developed in the low mountain range. Larger manorial farms and manors hardly played a role after the 17th century and, with a few exceptions, were destroyed in the course of the agricultural reforms of the 19th century. Of the former knights' estates, only the Schaumberg estates near Schalkau , Katzberg, Almerswind and Langemüß near Rotheul survived .

The agricultural constitution was shaped by the three-field economy until the first half of the 19th century . The associated Flurzwang existed not only in the districts of the villages of the low mountain range, but also in the cities of Sonneberg and Schalkau. Until the beginning of the agricultural reforms, mainly rye , wheat and spelled were grown in the fields . Since the 16th century, the cultivation of barley played a not insignificant role in the very extensive brewing industry ( beer brewing ). Rye and oats predominated in the vicinity of the early modern settlements in the low mountain range . More important than the agriculture was animal husbandry , which was operated during the 17th and 18th centuries in the highlands. At times, milk products in particular were exported to the Coburg area. Sheep breeding played an important role until the middle of the 19th century. There were larger sheep farms in Sonneberg, Effelder and Schalkau .

The first turning point in premodern agriculture was the introduction of the potato in the 18th century. Potato cultivation is documented for Neuhaus am Rennweg in 1721 and for Effelder in 1734. The potato prevailed particularly during the famine of 1770–1773. The potato became the dominant field crop, especially in the low mountain range.

The agricultural reforms of the 19th century intervened in the structures of agriculture through the abolition of the compulsory land, the introduction of more efficient cattle breeds and the replacement legislation . The replacement in particular strengthened the ownership of small and medium-sized farmers at the expense of the larger goods as well as the rural lower classes. Since the middle of the 19th century, the focus of the full-time farmers shifted to a strong dairy farming with root crops . At the same time, part-time farming expanded, especially in the low mountain range, which was a livelihood security for many families employed in the house industry until the 20th century. The state supported this part-time farming by spreading an improved meadow culture and promoting goat breeding .

The land reform implemented in the Soviet occupation zone from 1945 onwards had hardly changed the ownership structures because of the small proportion of larger - subject to expropriation - goods. This only changed with the establishment of the Agricultural Production Cooperatives (LPG) from 1952. The collectivization of agriculture in the district was largely complete in 1960. This change in ownership structures was linked to a changed management structure. Small-scale agriculture was replaced by large-scale agriculture in the low mountain range, while a large part of the agriculturally used areas in the low mountain range were abandoned.

The structural changes after 1990 led to a downsizing of agricultural enterprises. Few agricultural cooperatives and some resettlers have taken their place today . Dairy farming and the cultivation of feed grain and root crops are decisive in the foothills of the low mountain range. Potato growing has completely disappeared. Some companies are very successful in self-marketing. In addition to classic agriculture, there is also landscape maintenance , especially in the area of the Green Belt and in the Thuringian Slate Mountains. In this context, there is also an increase in sheep breeding.

forestry

With more than 60 percent forest area, the district of Sonneberg is one of the most wooded districts in Thuringia. For a long time, the forest was also the basis of many trades in the region. Since the late Middle Ages, the state, as the largest forest owner, has determined forest history . The forest areas in the Thuringian Slate Mountains, which are still closed today, go back to the once lordly forest ownership of the sovereigns , the so-called Franconian Forests , and are still exclusively state-owned. In contrast, private, corporate and church forests played only a subordinate role in the district. In addition to the fragmented, smallest forest parcels in the vicinity of several villages, there were larger private and corporation forests only near Bachfeld , Heinersdorf , Jagdshof , Schwärzdorf , Eichitz and Mürschnitz ; only the church forests near Heinersdorf and Meschenbach were significant as church forests .

The autochthonous beech-oak-fir forest (in the low mountain range) and the beech-fir-spruce forest (in the low mountain range) had already been largely displaced in the foreland during the high medieval development of the country. There were only closed forest areas on some mountain ranges or on low-yield sandy soils. The decline of the forest was largely stopped by the tighter forest supervision from 1555. In the stately forests , forest renovation began in the 16th century. Instead of arbitrary logging or clearing for glassworks , iron smelting , wood carving or ancillary forestry ( charcoal-burning , pitch extraction, etc.), there was a systematic clear-cutting economy with natural rejuvenation that favored the spruce . At the same time this intensified forest management went with the development of the manorial forests by rafting . The rafting for blocks and logs on the Steinach and Tettau was operated on a larger scale . In contrast, the log rafting in the area of the Röthen and Grümpen was of subordinate importance . The strongly fiscally motivated forest policy in Saxony-Coburg and from 1735 in Saxony-Meiningen - the forests provided an important part of the state income - led in the middle of the 18th century to the manorial forests being managed according to a strict sustainability principle . While, on the one hand, forest management was made more effective in favor of the chamber income, the wood procurement from glassworks and iron hammer works as well as the rights of use of the residents ( firewood equities , litter use , forest pasture ) were pushed back.

Particularly due to the introduction of the artificial foundation (around 1800), pure spruce forests had prevailed within the forests in the low mountain ranges from the middle of the 19th century. Hardly anything changed in this form of management in the state forests until the end of the 20th century. The spruce has retained its importance as the “bread tree” of the Thuringian Forest to this day. However, in addition to the classic management with clear-cut management and artificial stand foundations, alternatives are increasingly appearing that rely on a stronger mix of the stands and natural regeneration .

The state forests in the district are managed by the two Thuringian forest offices, Sonneberg and Neuhaus am Rennweg, both of which are also responsible for enforcing the forest law in non-state forests. In the smaller private, corporate and church forests, the older forest structures (deciduous and mixed forest) have been preserved to the present day. The forest cooperatives in Bachfeld , Mürschnitz and Heinersdorf could be restored from the corporation forests expropriated after 1945 . Much of the private forest owners has become single forest enterprise communities together (FBG).

Mining and raw material extraction

In the past, mining for gold , iron ore , colored earth ( ocher ), hard coal and slate were of greater importance .

The basis of the late medieval and early modern gold mining was the weak gold content of quartz veins on the southeast flank of the Schwarzburger saddle . Possibly motivated by the introduction of gold coins from the middle of the 13th century. Gold panning on the Schwarza and Grümpen rivers can be expected in the 19th century . In the 14th century the transition to gold mining probably took place. In 1362 Margrave Friedrich III. a mountain freedom for the gold mine near Steinheid . Gold mining was also mentioned in 1335 for the Apelsberg near Neuhaus am Rennweg , 1355 near Neuhaus-Schierschnitz and 1490 near Goldisthal . However, the gold mines near Steinheid and Goldisthal, some of which were operated with considerable technological effort between the 16th and 19th centuries, had no notable success.

Of greater importance than gold mining was the mining of Ordovician iron ores ( Ordovician ) on the south-eastern edge of the Schwarzburg saddle. The existence of iron hammers on the upper reaches of the Effelder , documented in 1441, presupposes this type of mining. Until the middle of the 19th century, iron ore mining was the basis for iron smelting in several steelworks . The mines were located at Mengersgereuth-Hammern , Steinach , Haselbach , Hasenthal and Spechtsbrunn . In 1868, when iron smelting was no longer competitive, iron ore mining in the district of Sonneberg was also discontinued.

Between the 18th and 20th centuries, the mining of colored earth (ocher) on the basis of iron-containing carbonates of the Silurian ( ocher lime ) was important at Mengersgereuth-Hammern, Steinach and Spechtsbrunn. Coal seams of the permosile were the basis for a coal mining operated between the 18th and 20th centuries near Neuhaus-Schierschnitz and Stockheim in Upper Franconia. Although the hopes of using hard coal for iron smelting were not fulfilled, mining continued into the 20th century. The coals were mainly sold for heating purposes and as forged coal . While this area was mined at Stockheim until 1968, coal mining was stopped at Neuhaus-Schierschnitz as early as 1912. In times of need, peat mining was important in Heubisch , Oberlind , Bettelhecken and Steinheid.

From 1949 to 1954, uranium mining was carried out by SDAG Wismut between Mengersgereuth-Hammern and Steinach . Similar efforts did not go beyond exploration in the Neuhaus-Schierschnitz area.

While ore and hard coal mining was only of secondary importance in the region, the mining of stone and earth played a much larger role. Already during the early Middle Ages, whetstones were extracted from suitable quartzites and quartzite slates from the Ordovician on Rennsteig and from Grauwacken in the Lower Carboniferous ( Dinant ) near Sonneberg and shipped to northern Germany. Later were shales of Devonian processed. The trade in whetstones from mining sites near Sonneberg, Mengersgereuth-Hammern, Siegmundsburg and Goldisthal has formed the basis of long-distance trade since the 16th century , which was concentrated in Sonneberg. The last whetstone quarries were closed in the middle of the 20th century.

The favorable structure of Ordovician slate (cleavage in two directions) formed the basis of style slate production since the 17th century. In place of small, individual mining sites and the in-house processing of the raw material, with the nationalization of the stylus quarries in 1891 there was mining in large open-cast mines and processing in central production facilities, so-called large smelters . The large penis slate quarries were near Steinach, Haselbach, Hasenthal and Spechtsbrunn. After underground mining was also started in 1935, pen slate mining was discontinued in 1968.

Also in the 17th century and in connection with the production of slate pens, Mengersgereuth-Hammern and Steinach began mining flat slate from lower carbon ( roof slate ), which was processed into slates . In the 18th century, slate production relocated to the Ludwigsstadt area . At times, the deposits near Steinach and Mengersgereuth-Hammern were also used for roofing slate production, but without ever being competitive with the large roofing slate quarries in Lehesten.

Sandstones of the middle red sandstone near Sonneberg, Mengersgereuth-Hammern, Schalkau and Steinheid were used for the extraction of stone between the 16th and 20th centuries. At the Sandberg near Steinheid, suitable sandstones were mined in the 18th and 19th centuries to be used as fire-resistant frame stones for blast furnaces. Kaolinized sandstones from the red sandstone near Steinheid (am Sandberg) and Neuhaus-Schierschnitz temporarily formed the basis of the local porcelain industry . A break at Mengersgereuth-Hammern yielded marble in the 18th century , which was also used in the Theres monastery church and the Saalfeld / Saale palace chapel .

The mining of Grauwacken for further processing into road construction material in the hard stone works Hüttengrund is still in operation today (as of 2013) .

Commercial and industrial

Assembly industry

Iron ore smelting

In addition to deposits of raw materials ( iron ore ), the main prerequisites for the development of a mining industry ( mining industry ) were primarily the resources of wood and watercourses suitable for driving hammer mills . Tied to the Ordovician iron ore deposits of the Thuringian Slate Mountains , an iron trade was established during the late Middle Ages. In 1441 there were several hammer mills on the rivers of Effelder near Mengersgereuth-Hammern and on the Steinach near Oberlind (Sonneberg) . These iron hammers may have been preceded by smelting near the ore deposits in the form of forest forges . Around 1460 an iron hammer was built near Blatterndorf ( Effelder-Rauenstein ), before 1464 there was also one in Hüttensteinach , in 1519 a racing fire was built in Steinach (Thuringia) , which was expanded into a hammer mill before 1528. Until the 17th century, the hammer mills were mainly geared towards supplying the Coburg care . A restrictive forest policy and the exhaustion of ore deposits near the surface led to the abandonment of some hammer mill sites in the 16th and early 17th centuries, such as Oberlind in 1578 and Blatterndorf (Effelder-Rauenstein) in 1653. The iron industry was modernized between 1604 and 1612 under Thomas Paul from Nuremberg . He had the existing hammer mills in the upper Steinach valley renewed, new hammer mills built at Blechhammer and a high furnace at Lauscha . In 1661 another hammer mill was built in Friedrichshöhe near Eschenthal . Further modernizations were carried out after the Thirty Years War in 1699 at the hammer mill in Obersteinach ( Steinach ) by Johann von Uttenhoven from Eibenstock in the Erzgebirge and in 1727 at the Augustenthal near Mengersgereuth-Hammern, where Georg Christoph von Uttenhoven took over a high furnace built in 1719 and expanded it into an iron and steel mill . The new plants built after the Thirty Years' War were geared towards export and, in addition to semi-finished products such as bar and line iron , also supplied sheet metal and cast iron products. The heyday of these works was in the 18th century.

Then a decline set in, which was determined equally by competition from other regions and by the scarcity of wood as a resource . In 1815 the hammer mill in Hüttensteinach and in 1836 the hammer mill in Friedrichsthal near Eschenthal ceased operations. The iron and steel works in Steinach and Augustenthal near Mengersgereuth-Hammern were taken over by the State of Saxony-Meiningen in 1844 , but operations in Augustenthal were discontinued in 1851. In Steinach, iron smelting was discontinued in 1867 and the company switched to the manufacture of cast iron products. The smelting works and rolling mills based on the use of hard coal , those in Blechhammer in 1836 and in Neuhaus-Schierschnitz in 1841 , could not hold their own and ceased operations in 1864 and 1868, respectively.

Copper ore smelting

Saigerhütten for the smelting of copper ore from Mansfeld existed between 1485 and 1518 in Hasenthal and between 1464 and 1561 in Hüttensteinach . The Saigerhütten had Nuremberg merchants built, for whom the region was attractive because of its wood stocks as well as the development through trunk roads ( Sattelpassstrasse ).

Glass industry

Glassworks

The basis for the location of the glassworks , which had been localized since the late Middle Ages, were large closed forests, the existence of sand and limestone deposits and the development of the region through national highways. During the 14th and 15th centuries, glassworks were concentrated in the low mountain range and in the southern edge of the low mountain range. The glassworks, which were only operated for a short time due to the enormous amount of wood used, are documented in writing for Judenbach (1418) and Rabenüßig (1455) as well as at several locations near Sonneberg , Mengersgereuth-Hammern and Siegmundsburg on the basis of archaeological finds.

The early modern glassworks were founded in connection with technological innovations, in particular a new type of furnace that enabled a higher output of glass, but at the same time had a higher demand for firewood. These new glassworks were permanently located and led to the emergence of glassworks settlements in 1595/97 Lauscha , 1607 Schmalenbuche , 1707 Ernstthal , 1711 Alsbach , 1728 Siegmundsburg, 1731 Limbach , 1736 Habichtsbach near Scheibe-Alsbach , 1736 Glücksthal near Neuhaus am Rennweg . The cooperative operation through the glass championship was characteristic of these village glassworks. Initially, only hollow glass was produced, which was sold throughout Europe. Since the middle of the 18th century, glass tubes were also manufactured as semi-finished products for glassblowers .

In the course of industrialization and a changed forest policy , the village glassworks fell into a crisis as early as the first half of the 19th century, which ultimately led to the closure of all village glassworks by 1900. In contrast, from the middle of the 19th century, modern, industrially oriented glassworks were built, based on coal-fired firing. Between 1853 and 1856 three modern glassworks were built in Lauscha. Further glassworks were built in Haselbach in 1896 and in Ernstthal in 1923. In addition to classic products such as hollow glass and tubes, glass fibers and container glass appeared from the end of the 19th century . Hollow glass and tubes are currently manufactured in Lauscha, glass fibers in Lauscha and Haselbach and container glass in Ernstthal.

traffic

Old streets

The area of today's district of Sonneberg was crossed by old streets in prehistoric times . This was once a north-south connection between the upper main valley around Bamberg and the Saale valley near Saalfeld , which ran east of the Steinach and reached the low mountain range at Hüttensteinach and crossed the slate mountains along the route of the late medieval saddle pas road via Judenbach and Graefenthal . Another old road crossed the region from southeast to northwest. This route came from the Kronach area , overcame the plain south of Sonneberg and reached the Werra valley via Neustadt near Coburg , Effelder and the ridges south of Schalkau near Eisfeld . A use of both old streets can be made likely for the younger Bronze Age due to archaeologically documented cultural connections between northeast Bavaria, eastern Thuringia and the Werra Valley in southern Thuringia .

The most important traffic connection in the late Middle Ages and early modern times was the Sattelpasstraße, which was mentioned in writing in 1394 as “straße above den Judenbach ” and in 1414 as “ Judenstraße ”. Since the end of the 15th century part of the escort road Nuremberg - Leipzig , the Sattelpasstraße was one of the most important long-distance roads of the Coburg up until the mid-16th century . Of national importance was also for the region in addition to the semi-pass road Rennsteig , 1394 as "road above Gräfenthal after Steynen Gentile" ( Steinheid called), is to address also the old route in its eastern part.

Streets

The construction of modern art roads , so-called Chausseen , was intensively pursued by the Principality of Saxony-Coburg-Meiningen from the end of the 18th century. In 1807 the Chaussee Eisfeld - Sonneberg was completed. As further road construction works followed Sonneberg- Steinach (Thuringia) through the Röthengrund (1811), Sonneberg- Neustadt near Coburg (1821–1826), Eisfeld- Steinheid - Neuhaus am Rennweg (1823–1829), Sonneberg- Kronach (1838–1849), Sonneberg- Mupperg (1838–1840), Sonneberg- Gräfenthal (1843–1850) and Schalkau - Limbach (1853). With the Reichsfernstraßengesetz (1934) the connections Meiningen - Burggrub (district Kronach) as Reichsfernstrasse 89 (today federal highway 89 ) and Eisfeld (district Hildburghausen ) - Mittelpöllnitz (district Saale-Orla-Kreis ) as Reichsfernstrasse 281 (today federal highway 281 ) became part of national trunk road network of Germany. Both federal roads are still the most important road connections in the district.

railroad

First efforts to develop the Sonneberg area by railways date back to the 1830s. The Coburg – Sonneberg railway line was built in 1858 through the Werra Railway project operated by Joseph Meyer . This section and the extension to Lauscha, which went into operation in 1886, were operated by the Werra Railway Company , which was taken over by the Prussian State Railway (KPStE) in 1895 . In 1896, with the construction of the Probstzella – Bock-Wallendorf line , the Prussian State Railroad connected today's district to the Frankenwald Railway . The Prussian State Railways also extended the Sonneberg-Stockheim (Upper Franconia) (1900/01), Sonneberg-Eisfeld (1910) and the extension of the Coburg-Lauscha to Ernstthal (1911-1913) line, where connection to the Bock- Wallendorf to Neuhaus am Rennweg extended route from Probstzella existed, planned and built. The Bavarian State Railway touched the area of the district with its branch line from Pressig-Rothenkirchen to Tettau near Heinersdorf, which opened in 1903 . Soon after the establishment of the Deutsche Reichsbahn , the Heubisch-Mupperg station was served by the Steinachtalbahn in 1920 .

With the very extensive route network (1920: 83 kilometers), Sonneberg had become a railway junction. When the local train station went into operation (1907), Sonneberg became a locomotive station that remained subordinate to the Coburg depot .

As a result of the division of Germany , several lines were shut down, for example in 1945 parts of the Steinach Valley Railway between Sonneberg and Mupperg and the Sonneberg-Stockheim (Upper Franconia) line between Neuhaus-Schierschnitz and Burggrub (Stockheim) Neuhaus-Schierschnitz-Burggrub. 1951 ended the traffic between Sonneberg and Neustadt bei Coburg . In 1952, traffic on the Pressig-Rothenkirchen-Tettau railway was also interrupted. On the remainder of the Sonneberg- Neuhaus-Schierschnitz line , passenger traffic was discontinued in 1967 and freight traffic in 1970. The Sonneberg train station remained a locomotive operating site after 1945 and was subordinate to the Probstzella depot. Due to the sharp increase in freight traffic in the Sonneberg area, a container railway station was built in Sonneberg East (1970), but it ceased operations in 1995.

In 1991, after extensive construction work, the interrupted traffic between Sonneberg and Neustadt bei Coburg was resumed. In 1997, the traffic on the routes Sonnenberg Probstzella and Sonneberg- were ice rink by the German train set. After major renovation work, the South Thuringia Railway resumed on the Sonneberg-Eisfeld and Sonneberg-Neuhaus routes on Rennweg (64 kilometers) in 2002 . The Sonneberg-Coburg-Lichtenfels line is operated by Deutsche Bahn. Today Sonneberg can also be reached with the Bayernticket .

In 2005, construction work began on the new Ebensfeld-Erfurt line in the district of Sonneberg .

Protected areas

There are 19 designated nature reserves in the district (as of January 2017).

Healthcare

- REGIOMED-Klinikum Sonneberg : with houses in Sonneberg and Neuhaus am Rennweg as part of REGIOMED-Kliniken

- The district of Sonneberg is the only district outside of Bavaria that belongs to the health region Erlangen NeuroRegioN - TelemedNordbayern

Communities

Neuhaus am Rennweg / Lauscha (functionally divided) and Sonneberg are designated as medium-sized centers according to the regional plan.

The basic centers are the cities of Schalkau and Steinach .

(Residents on December 31, 2019)

|

community-free municipalities |

|

For the terms "administrative community" and "fulfilling community" see administrative community and fulfilling community (Thuringia) .

Territorial changes

Communities

The following communities in the district of Sonneberg lost their independence by 1994:

|

|

Since 1995 there have been further incorporations and new formations:

- Dissolution of the Ernstthal community - incorporation into the city of Lauscha (November 17, 1995)

- Dissolution of the communities Engnitzthal and Haselbach - new formation of the community Oberland am Rennsteig (January 1, 1997)

- Dissolution of the Heinersdorf community - incorporation into the Judenbach community (January 1, 1997)

- Dissolution of the Steinheid community - incorporation into the town of Neuhaus am Rennweg (December 1, 2011)

- Dissolution of the municipalities of Effelder-Rauenstein and Mengersgereuth-Hammern - new formation of the municipality of Frankenblick (January 1, 2012)

- Dissolution of the communities Scheibe-Alsbach and Siegmundsburg - incorporation into the city of Neuhaus am Rennweg (December 31, 2012)

- Dissolution of the municipality of Oberland am Rennsteig - incorporation into the city of Sonneberg (December 31, 2013)

- Dissolution of the communities of Föritz , Judenbach and Neuhaus-Schierschnitz - merger to form the community of Föritztal (July 6, 2018)

- Dissolution of the communities of Lichte and Piesau from the district of Saalfeld-Rudolstadt - incorporation into the city of Neuhaus am Rennweg (January 1, 2019)

- Dissolution of the Bachfeld community - incorporation into the city of Schalkau (December 31, 2019)

Administrative communities and fulfilling communities

- Dissolution of the administrative community Schalkau - Schalkau becomes a fulfilling municipality for Bachfeld (July 27, 1995)

- The town of Neuhaus am Rennweg becomes a fulfilling municipality for Goldisthal , Scheibe-Alsbach and Siegmundsburg (January 1, 1997)

- The city of Steinach becomes a fulfilling municipality for Steinheid (January 1, 1997)

- The city of Steinach is no longer a fulfilling municipality for Steinheid (November 30, 2011)

- The city of Neuhaus am Rennweg is no longer a fulfilling municipality for Scheibe-Alsbach and Siegmundsburg (December 31, 2012)

- The city of Schalkau is no longer a fulfilling municipality for Bachfeld (December 31, 2019)

Dialects in the district area

A Main Franconian dialect, Itzgründische , is predominantly spoken in the district. In the cities and towns on Rennsteig is Ilmthüringisch and Südostthüringisch spoken. The border between the Itzgründisch and the Thuringian dialects runs along the Rennsteig, but extends beyond it in the area of the district to the south. The so-called Bamberg barrier , which separates the Upper Franconian from the Main Franconian language area, largely coincides with the eastern border with the Kronach district . Only the places Heinersdorf (community Judenbach ) and Rotheul (community Neuhaus-Schierschnitz ) are beyond the Bamberg barrier and thus in the Upper Franconian-speaking area.

License Plate

At the beginning of 1991 the district received the distinctive sign SON . It is still issued today. The distinguishing mark NH (Neuhaus am Rennweg) has been available since November 24, 2012 .

literature

- Between Rennsteig and Sonneberg (= values of our homeland . Volume 39). Akademie Verlag, Berlin 1983, DNB 840099045 .

- Denny Jahn: District of Sonneberg. In: Peter Sedlacek (Ed.): The districts and independent cities of the Free State of Thuringia (= Thuringia yesterday & today, 14). State Center for Political Education Thuringia, Erfurt 2001, ISBN 3-931426-58-0 , pp. 207–215.

- Thomas Schwämmlein: District of Sonneberg (= monument topography of the Federal Republic of Germany. Cultural monuments in Thuringia 1). E. Reinhold Verlag, Altenburg 2005, ISBN 3-937940-09-X , pp. 563-588.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Population of the communities from the Thuringian State Office for Statistics ( help on this ).

- ↑ radioeins.com ( Memento from December 19, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Radio Eins: Clear vote in favor of Franconia.

- ↑ MDR: April 2, 2014: Also the district of Sonneberg in the metropolitan region of Nuremberg ( Memento from April 7, 2014 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Walter Heins: royal estate and landlords in the eastern grave field during the Carolingian era. In: Friedrich Schilling (Ed.): Coburg in the middle of the realm. Volume I, Kallmünz 1956, pp. 91-116; Rainer Hambrecht: The first mention of Rodach in the context of state and imperial history. In: Rodacher Almanach 1986. Special contributions to the local history of the Coburg country. (= Writings of the Rodacher Rückert-Kreis. 10). Rodach 1986, pp. 9-29.

- ↑ Helmut Demattio: Kronach. The Altlandkreis. (= Historical Atlas of Bavaria. Part Franconia. I / 32). Munich 1998, pp. 34-37; Helmut Demattio: The Sterkere - Counts of Wohlsbach. In: Ferdinand Kramer, Wilhelm Störmer (Hrsg.): High Middle Ages noble families from Old Bavaria, Franconia and Swabia. (= Studies on Bavarian Constitutional and Social History. 20). Munich 2005, pp. 241-270; Rainer Hambrecht: Contributions to the founding, ownership and economic history of the Mönchröden Monastery. In: Reinhard Butz, Gerd Melville (ed.): 850 years of Mönchr-öden. The former Benedictine abbey from the first documentary mention in 1149 until the Reformation. (= Series of publications of the Historical Society Coburg. 13). Coburg 1999, pp. 65-118.

- ↑ Walter Heins: royal estate and landlords in the eastern grave field during the Carolingian era. In: Friedrich Schilling (Ed.): Coburg in the middle of the realm. Volume I, Kallmünz 1956, pp. 91-116; Friedrich Schilling: The Ur-Coburg and its surrounding area in the light of the late Tonic empire history. In: Friedrich Schilling (Ed.): Coburg in the middle of the realm. Volume I, Kallmünz 1956, pp. 117-183; Helmut Talazko: Moritzkirche and Propstei Coburg. A contribution to the history of spiritual fortunes in the late Middle Ages. (= Individual works on the church history of Bavaria. 2). Nuremberg 1971.

- ↑ Erich Fhr. Von Guttenberg: The formation of territories on the Obermain. (= Report of the Bamberg Historical Society. 79). Bamberg 1926, p. 437 f .; Walter Lorenz: Campus solis. History and property of the former Cistercian abbey of Sonnefeld near Coburg. (= Writings of the Institute for Franconian State Research at the University of Erlangen. Historical series. 6). Kallmünz 1955; Thomas Schwämmlein: On the first mention of the name "Sonneberg". Source, tradition, historical context. In: Yearbook of the Hennebergisch-Franconian History Association. 22 (2007), pp. 43-59.

- ^ Oskar Frhr. von Schaumberg, Erich Freiherr von Guttenberg: Regesten of the Franconian family von Schaumberg. A contribution to the history of the Itz and Obermainlande. I. part. 1216-1300. (= Coburg local history and local history. Second part. Local history. 12). Coburg 1930; Regest of the Franconian family von Schaumberg. A contribution to the history of the Itz and Obermainlande. Part II. 1301-1400. (= Coburg local history and local history. Second part. Local history. 17). Coburg 1939; Thomas Schwämmlein: Schaumberg and Schalkau. Castle, town and center in the Middle Ages. In: Schaumberg-Schalkau. Castle, town, church. Schalkau 2000, pp. 11-58.

- ↑ Wilhelm Füßlein: Hermann I. Graf von Henneberg (1224-1290) and the upswing in Henneberg politics. From the emancipation of the Henneberger from burgrave office to their participation in the anti-kingship. In: Journal of the Association for Thuringian History and Archeology. 19 (1899), pp. 56-109, 151-224, 295-342; Wilhelm Füßlein: The acquisition of the lordship of Coburg by the House of Henneberg-Schleusingen in the years 1311-1316. In: Writings of the Henneberg Historical Society. 15: 51-132 (1928); Eckart Henning: The new rule Henneberg 1245-1353. In: Yearbook of the Coburg State Foundation. 26, pp. 43-70 (1981); Johannes Mötsch: The Counts of Henneberg and the Coburg region in the 13th and 14th centuries. In: Reinhard Butz, Gerd Melville (eds.): Coburg 1353. City and Country Coburg in the Late Middle Ages. Festschrift for the connection of the Coburg country with the Wettins from 650 years ago until 1918. (= series of the historical society Coburg. 17). Coburg 2003, pp. 129-138.

- ↑ Wilhelm Füßlein: The transition of the rule Henneberg Coburg from the house of Henneberg-Schleusingen to the Wettiner 1353. In: Journal of the association for Thuringian history and antiquity. 36: 325-434 (1929); Reinhardt Butz: The Wettin and the Coburg country from 1351 until the death of Margrave Friedrich III. von Meißen 1381. In: Reinhardt Butz, Gerd Melville (Hrsg.): Coburg 1353. City and country of Coburg in the late Middle Ages. Festschrift for the connection of the Coburg country with the Wettins from 650 years ago until 1918. (= series of the historical society Coburg. 17). Coburg 2003, pp. 139–157.

- ^ Walter Lorenz: The history of the large parish Fechheim in the Middle Ages. In: North Franconian monthly sheets. (1954) H. 9, pp. 453-471.

- ↑ Ulrich Heß: History of the organization of the authorities of the Thuringian states and the state of Thuringia from the middle of the 16th century to 1952. (= publications of the historical commission for Thuringia. Small series. 1). Jena / Stuttgart 1993, p. 39.

- ↑ Wolfgang Huschke: Political history from 1552 to 1775. In: Hans Patze, Walter Schlesinger (Hrsg.): Geschichte Thüringens. Volume 5: Political History in Modern Times. Volume 1. (= Central German Research. 48). Cologne / Vienna 1985, pp. 1-614; Schwämmlein, district of Sonneberg, p. 25.

- ↑ Huschke, Politische Geschichte, p. 469 f.

- ↑ Ulrich Heß: The enlightened absolutism in Saxony-Meiningen. In: Research on the Thuringian regional history. (= Publications of the Thuringian Main State Archives Weimar. 1). Weimar 1958, pp. 1-42, here p. 21; Katharina Witter: On the administrative organization of the Sachsen-Coburg-Meiningischen Land towards the end of the 18th century. In: Duke Georg I of Saxony-Meiningen. A precedent for enlightened absolutism? (= South Thuringian Research. 21). Meiningen 2004, pp. 55–67, here p. 58 f.

- ↑ Hess, Organization of Authorities, p. 43.

- ^ Hess, organization of the authorities, p. 100.

- ↑ Helmut Demattion: The rule of Lauenstein until the end of the 16th century. The historical and constitutional development of a clearing rule in the Thuringian Forest. (= Publications of the Historical Commission for Thuringia. Small series. 3). Jena 1997.

- ↑ Huschke, Politische Geschichte, p. 60.

- ↑ Huschke, Politische Geschichte, p. 526 ff .; Hans Tümmler: The Age of Carl August von Weimar 1775-1828. In: Hans Patze, Walter Schlesinger (Hrsg.): History of Thuringia. Volume 5: Political History in Modern Times. Volume 2. (= Central German Research. 48). Cologne / Vienna 1984, pp. 615–780, here pp. 697 ff.

- ^ Immo Eberl: The early history of the Schwarzburg house and the formation of its territorial rule. In: Thuringia in the Middle Ages. The Schwarzburger. (= Contributions to the Schwarzburg art and cultural history. 3). Rudolstadt 1995, pp. 79-130.

- ^ Ulrich Heß: History of the state authorities in Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt. (= Publications of the Historical Commission for Thuringia. Large series. 2). Jena / Stuttgart 1994, p. 3.

- ↑ Hess, State Authorities, Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt, pp. 39 ff., 87 ff.

- ^ Frank Boblenz: City and rural districts in Thuringia 1920–1998. In: Bernhard Post (ed.): Thuringia manual. Territory, constitution, parliament, government and administration in Thuringia 1920–1995. (= Publications from Thuringian state archives. 1). Weimar 1999, p. 474-539, here p. 526 f.

- ↑ Boblenz, Stadt- und Landkreise, p. 527.

- ↑ Boblenz, Stadt- und Landkreise, p. 526 f .; Thomas Schwämmlein: July 25, 1952 - the Neuhaus am Rennweg district is established. Prehistory, emergence and beginnings of an administrative structure in the context of national and regional history. In: District of Sonneberg. Tradition and future. 8 (2003), pp. 136-144.

- ^ Thuringian territorial reform ( Memento from November 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on February 5, 2013.

- ↑ Bayerischer Rundfunk, May 23, 2014: Metropolitan Region Nuremberg. Sonneberg becomes a member outside of Bavaria

- ↑ Sonneberg and Hildburghausen threaten to flee to Franconia. on: insuedthueringen.de , February 2, 2013, accessed on February 5, 2013.

- ↑ preliminary law on functional and territorial reform on thueringen.de, accessed on June 16, 2019

- ↑ thueringen.de , accessed on October 11, 2016

- ↑ Article in the Ostthüringer Zeitung , accessed on October 19, 2016

- ↑ 3,000 people demonstrate against territorial reform. (No longer available online.) MDR Thuringia, May 8, 2017, archived from the original on May 26, 2017 ; Retrieved May 19, 2017 .

- ↑ Demo in Sonneberg: Why Francs are also against the territorial reform. Thuringia 24, 16 May 2017, accessed on 19 May 2017 .

- ↑ Bill of June 19, 2018 , accessed December 15, 2018

- ↑ administrative history.de: District of Sonneberg

- ↑ 1946 census

- ↑ Data source: from 1994 Thuringian State Office for Statistics - values from December 31st

- ↑ a b District election 2019 in Sonneberg . In: wahlen.thueringen.de

- ↑ District election 1994 in Sonneberg . In: wahlen.thueringen.de

- ↑ District election 1999 in Sonneberg . In: wahlen.thueringen.de

- ↑ District election 2004 in Sonneberg . In: wahlen.thueringen.de

- ↑ District election 2009 in Sonneberg . In: wahlen.thueringen.de

- ↑ District election 2014 in Sonneberg . In: wahlen.thueringen.de

- ^ Traveling exhibition 150 years of the Sonneberg district. (PDF; 6.8Mb) District of Sonneberg, accessed on July 31, 2019 .

- ↑ Jochen Lengemann (Ed.): Parliaments in Thuringia 1809–1952. Thuringian state parliaments 1919–1952. Biographical manual. (= Publications of the Historical Commission for Thuringia. Volume 1. Part 4). Cologne 2014, p. 390 f.

- ↑ Jochen Lengemann (Ed.): Parliaments in Thuringia 1809–1952. Thuringian state parliaments 1919–1952. Biographical manual. (= Publications of the Historical Commission for Thuringia. Volume 1. Part 4). Cologne 2014, p. 195 f.

- ↑ Free word

- ↑ Zukunftsatlas 2016. Archived from the original ; accessed on March 23, 2018 .

- ↑ Sponge: District of Sonneberg. P. 29 f.

- ^ Simone Müller: Sheep farming in Thuringia and Franconia. In: Wolfgang Brückner (Ed.): Home and work in Thuringia and Franconia. On the folk life of a cultural region. Würzburg / Hildburghausen 1996, pp. 93-97.

- ^ Friedrich Timotheus Heim: Topography of the Parish Game Effelder 1808–1814. Effelder 1993, p. 54; Andrea Jakob: Insights into the beginnings of potato cultivation in Thuringia. In: Frau Holle. Myth, fairy tale and custom in Thuringia. Meiningen 2010, pp. 202-214.

- ^ Thomas Schwämmlein: Modern Agricultural Funding in South Thuringia. In: Wolfgang Brückner (Ed.): Home and work in Thuringia and Franconia. On the folk life of a cultural region. Würzburg / Hildburghausen 1996, pp. 75-79; Schwämmlein, Economic Policy Fields of Action, pp. 78–80.

- ↑ Thomas Schwämmlein: The southern Thuringian agriculture after 1945. In: Wolfgang Brückner (Hrsg.): Home and work in Thuringia and Franconia. On the folk life of a cultural region. Würzburg / Hildburghausen 1996, pp. 89-92.

- ↑ Thomas Schwämmlein: Forest and Forest in the Principality of Coburg and in the "Franconian Forests" during the high and late Middle Ages. (= Publication series history and charcoal burner association Mengersgereuth-Hammern. 16). Mengersgereuth hammers 2006.

- ↑ August Freysoldt: The Franconian forests in the 16th and 17th centuries. A contribution to the forest history of the Meininger Oberland. Steinach 1904; Hans von Minckwitz: The influence of humans on the forest image of the Thuringian slate mountains up to the beginning of the 18th century. In: Archives for Forestry. 11 (1962), pp. 919-979.

- ↑ Max Volk: The rafting from the Franconian forests. In: Yearbook of the Coburg State Foundation. 12 (1967), pp. 43-104.

- ↑ Ulrich Heß: The Oberland forests in the 18th and 19th centuries. In: monthly program. Kulturbund for the democratic renewal of Germany. Sonneberg district. District of Neuhaus / Rwg. (1954), H. 2, pp. 1-14; Hans von Minckwitz: On the forest history of the state forestry enterprise Sonneberg up to the middle of the 19th century. In: Archives for Forestry. 5 (1956), pp. 457-486; Thomas Schwämmlein: Fields of economic policy in enlightened absolutism. The small state of Saxony-Meiningen under Georg I. In: Duke Georg I of Saxony-Meiningen. Eon precedent for enlightened absolutism? (= South Thuringian research. 33). Meiningen 2004, pp. 68–95, here pp. 75–78.

- ↑ thueringen.de

- ↑ Hans Hess von Wichdor: The gold deposits of the Thuringian Forest and Franconian Forest and the history of Thuringian gold mining and gold washing. Berlin 1914; Herbert Kühnert: Some new documentary statements about the former gold mining and gold panning in the Schwarza river basin. In: The Thuringian Flag. 2 (1933), H. 11, pp. 650-654; Herbert Kühnert: Old and new on the history of gold mining near Steinheid in the Thuringian Forest. In: The Thuringian Flag. 5 (1936), H. 11, pp. 513-528; Thomas Schwämmlein: Technological innovations in gold mining in Thuringia in the 16th century. In: Sheets of the Association for Thuringian History. 8 (1998), H. 1, pp. 17-21; Markus Schade: Gold in Thuringia. Thuringian Forest, Slate Mountains, Franconian Forest. Origin, creation, points of discovery. Weimar 2001; Thomas Schwämmlein: Gold panning and gold mining in the Grümpen river area, district of Sonneberg. Results of a mining archaeological survey. In: Old Thuringia. 27 (2001), pp. 284-303; Thomas Schwämmlein: The resumption of the Steinheider gold mining in the context of the Coburg regional, financial and economic history at the end of the 17th century. In: Coburg history sheets. 11 (2003), H. 1/2, pp. 29-37; Egon Krannich among others: Gold on the Steynernen Heide. 475 years of the free mountain town of Steinheid. Grimma 2005.

- ↑ Herbert Kühnert: A foray into the older history of mining and metallurgy in the former Coburg nursing home. In: Yearbook of the Coburg State Foundation. 10, pp. 211-264 (1965); Peter Lange: The end of iron smelting in today's district of Sonneberg (1830–1870). (= Series of publications Museumsverein Schieferbergbau Steinach. 72). Steinach 1998; Peter Lange: The development of iron metallurgy with special consideration of the conditions in Mengersgereuth hammers. (= Series of history and charcoal burners. 6). Mengersgereuth hammers 2002; Thomas Schwämmlein: The beginnings of iron ore mining and smelting in the area of the Sonneberg district. On the problem of medieval mining history in southern Thuringia. In: Yearbook of the Hennebergisch-Franconian History Association. 9 (2004), pp. 37-71.

- ↑ Jochen Vogel: The real Vettersche Goldocker. 220 years of earth color extraction and processing in the Hammern-Steinach area. Mengersgereuth hammering 2001.

- ^ Rudolf Herrmann: On the history of the Neuhaus-Stockheimer hard coal mining. In: Journal of Applied Geology . 2: 483-488 (1956); Ulrich Heß: The last decade of hard coal mining in Neuhaus near Sonneberg. In: Culture mirror for the districts of Sonneberg and Neuhaus / Rwg. (1958), H. 12, pp. 251-258, (1959), H. 1, pp. 275-280; Walter Heinlein among others: Coal mining around Stockheim 1756–1968. Stockheim 1989; Gerd Fleischmann: Coal mining. Stockheim, Neuhaus, Reitsch. Stockheim 1990.

- ^ Adolf Hoßfeld: The peat extraction in and around Sonneberg between 1840 and 1950. (= series of publications Sonneberger Museums- und Geschichtsverein. 3/97). Sonneberg 1997.

- ↑ Jochen Vogel: Why did the SAG / SDAG Wismut come to Steinach? (= Series of publications Museumsverein Schieferbergbau Steinach, 149). Steinach 2009.

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Bautsch, Josef Rieder: On the origin of the whetstones from the excavation on the castle wall in Berlin-Spandau. In: Peter Dilg ua (Ed.): Rhythm and Seasonality. Congress files of the 5th symposium of the Medievalist Association in Göttingen 1993. Sigmaringen 1995, pp. 423–432; Thomas Schwämmlein: Manufacture and trade in whetstones in the area of the Thuringian Slate Mountains during the early and high Middle Ages. Facts and hypotheses. (= Publication series history and charcoal burner association Mengersgereuth-Hammern, 21). Mengersgereuth hammering 2008.

- ↑ Max Volk: Whetstones. In: Hallesches Jahrbuch für Mitteldeutsche Erdgeschichte. 3 (1958) H. 1, pp. 61-67; Max Volk: The slate layers of the upper Kulm and their industrial importance. In: Journal of Applied Geology . 6: 58-63 (1964); Max Volk: The whitish slate deposits in the phycode series from Mengersgereuth-Hammern, Steinach and Graefenthal (Thuringian Forest). In: Hallesches Jahrbuch für Mitteldeutsche Erdgeschichte. 7: 61-67 (1965); Max Volk: The Hiftenberger whetstone quarries. In: Hallesches Jahrbuch für Mitteldeutsche Erdgeschichte. 8, pp. 92-96 (1966); Thomas Schwämmlein: Whetstone mining and whetstone production in the Sonneberg district. (= Publication series history and charcoal burner association Mengersgereuth-Hammern, 8). Mengersgereuth hammers 2003; Gerhard Weise: The use of Thuringian stones for the production of whetstones. In: Contributions to the geology of Thuringia. NF 12 (2005), pp. 71-97.

- ^ Alfred Weidmann: The German natural slate industry and its sales organization. Lippstadt 1929; Max Volk: History of the pen industry. Steinach 1948; Schwämmlein, District of Sonneberg, pp. 141–145.

- ↑ Peter Lange, Heinz Pfeiffer: The slate mining on the western edge of the Teuschnitzer Mulde (South Thuringia-Upper Franconia). In: Memorial colloquium for the 100th birthday of Bruno von Freyberg. (= Sonneberger contributions to applied geosciences. 1). Steinach 1994, pp. 35-48.

- ↑ Max Volk: The rock deposits in the Sonneberg district and their significance for the development of the branches of industry. In: Material for home studies. Sonneberg district (Suhl district). Part 2. Sonneberg 1955, pp. 13-15; A. Kaiser: The porcelain sand pit. In: Material for home studies. Sonneberg district (Suhl district). Part 1. Sonneberg 1955, p. 28 f .; Ottomar Kröckel: The use of local raw materials. Basis for the production of electro-ceramic products. In: Hermsdorfer Technische Mitteilungen. 15 (1975), H. 42, p. 1324 f.

- ↑ Joachim Kern: The hard stone factory Hüttengrund HWH. In: District of Sonneberg. Tradition and future. 9 (2004), p. 174 f.

- ↑ Kühnert, A foray through the older history of mining and metallurgy; Little sponges, beginnings of iron ore mining and smelting; Lange, development of ferrous metallurgy.

- ↑ Lange, End of the iron smelting.

- ^ Horst Wagenblass: The Deutsche Eisenbahnschienen-Compagnie and its founder Carl Joseph Meyer. A contribution to the history of the great bad investments in early German industrialism. In: Tradition. Journal for company history and entrepreneur biography. 17 (1972), H. 5/6, pp. 233-255; Stefan Löffler: Joseph Meyer and Neuhaus-Schierschnitz. (= Series of publications Sonneberger Museums- und Geschichtsverein. 1/96). Sonneberg 1996.

- ↑ Kühnert, A foray through the older history of mining and metallurgy; Peter Lange: The Steinacher Saiger trading company under the Judenbach. (= Series of publications Heimatstube Schieferbergbau. 11). Steinach 1989; Helmut Demattio: The large-scale economic development and use of remote forest areas in the late Middle Ages and at the beginning of the modern era. The establishment of so-called Saigerhütten in the south-eastern Thuringian Forest and its consequences for forestry. In: Egon Gundermann, Karl-Reinhard Volz (Ed.): Forest research reports. (1997), pp. 1-17.

- ^ Herbert Kühnert: Document book on the Thuringian glassworks history. (= Contributions to Thuringian history. 2). Jena 1934, pp. 1-20.

- ^ Kühnert, document book; Rudolf Hoffmann: Thuringian glass from Lauscha and the surrounding area. Leipzig 1993, pp. 14-24; Helena Horn: 400 years of glass from Thuringia. The collection of the Museum for Glass Art Lauscha. A selection. Lauscha 1995, pp. 25-29.

- ↑ Hoffmann, Thüringer Glas from Lauscha, pp. 24–28.

- ^ Julius Rebhan: The saddle pass road. A section of the Nuremberg-Leipzig military and trade route between Obermain and the upper Saale valley near Saalfeld. (= Series of publications by the German Toy Museum in Sonneberg). Sonneberg 1966; Schwämmlein, district of Sonneberg, pp. 20–22; Thomas Schwämmlein: Ice field and its traffic routes. From the old road to the motorway. In: Eisfeld in the past and present. Ceremony for the 1200th anniversary of the first mention of Asifeld-Eisfeld. Eisfeld 2001, pp. 18-28.

- ↑ Schwämmlein, district of Sonneberg, pp. 145–147.

- ^ Deutsche Bahn

- ^ Wolfgang Beyer: Railway in the Sonneberger Land. Coburg 1997; Konrad Schliephake: Transport development by rail. In: Wolfgang Brückner (Ed.): Home and work in Thuringia and Franconia. On the folk life of a cultural region. Würzburg / Hildburghausen 1996, pp. 51-56; Schwämmlein, District of Sonneberg, pp. 147–155.

- ↑ Bavarian State Ministry for Environment and Health - Health Region Erlangen NeuroRegioN - TelemedNordbayern ( Memento from November 27, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Regional plan Southwest Thuringia from February 22, 2011 , accessed on October 16, 2016

- ↑ Heinz Rosenkranz: The Thuringian language area. Investigations into the dialect geographical situation and the linguistic history of Thuringia. (= Central German Studies. 26). Hall / S. 1964, pp. 195-198; Heinz Rosenkranz: The linguistic basics of the Thuringian area. In: Hans Patze, Walter Schlesinger (Hrsg.): History of Thuringia. Volume 1: Basics and the Early Middle Ages. (= Central German research. 48 / I). Köln / Wien 1985, pp. 113–173, here pp. 126–132; Emil Luthardt: Dialect and folk from Steinach, Thuringian Forest, and dialect geographic studies in the Sonneberg district, in the Eisfeld district court, Hildburghausen district, and in Scheibe in the Oberweißbach district court, Rudolstadt district. Diss. Hamburg 1963 [MS]; Heinz Sperschneider: vernacular. In: Frankdieter Grimm among others: Between Rennsteig and Sonneberg. Results of the local history inventory in the areas of Lauscha, Steinach, Schalkau and Sonneberg. (= Values of our homeland. 39). Sonneberg 1983, pp. 27-31; Monika Fritz-Scheuplein, Almut König: Linguistic unity of the region. In: Wolfgang Brückner (Ed.): Home and work in Thuringia and Franconia. On the folk life of a cultural region. (= Country and people). Würzburg / Hildburghausen 1996, pp. 33-37; Heinz Sperschneider: The dialects of our homeland in the German language landscape. (= Series of history and charcoal burners. 1). Mengersgereuth hammering 2000.