European refugee crisis

The European refugee crisis (also European migration crisis or just asylum crisis ) is the sharp increase in the number of asylum seekers in the EU states associated with the entry and transit of 1–2 million refugees into the European Union in 2015/16 also understood in the following the ongoing migratory pressure on Europe and the overall social impact of this refugee movement .

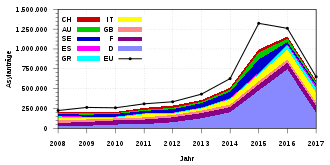

The number of asylum seekers who entered Europe had already reached 627,000 in 2014, almost doubled to over 1.3 million in 2015 and was again 1.26 million in 2016, a large proportion of whom had already arrived in 2015 but were recorded late has been. After the tightening of asylum law in the most important target states in autumn 2015, the establishment of border barriers on the Balkan route in March 2016 and the EU-Turkey agreement of March 18, 2016 , the number of new asylum seekers fell rapidly and was around 650,000 in 2017.

The events revealed various shortcomings in the EU's asylum system: in the course of the crisis, some EU states disregarded central agreements from the Schengen Agreement of 1985 and the Dublin Agreement of 1990 and refused to distribute the refugees. That called into question the viability of the EU treaties, the integrative power of the EU and intra-European solidarity . The asylum policy of the European Union , the European migration policy and the respective national immigration and refugee policies , as well as the position of Islam in Europe, became the subject of the most heated political disputes. At the national level, the crisis led to a strengthening of the political right as well as national conservative and Islamophobic forces.

Designations

"Refugees", "Refugees", "Asylum seekers", "Migrants"

“Refugees” or “refugees” and “asylum seekers” are not precisely differentiated from “migrants” in the general usage of the current crisis. Today the term includes those affected by forced, voluntary or involuntary migration, not only those persecuted by the state. Since the causes and motives of migration change and merge in a variety of ways, categories that are delimited from one another are usually external attributions on the part of the host countries.

"Refugee crisis"

Larger within and outside Europe refugee movements are colloquially long been known as "refugee crisis" means, the mass exodus from the GDR during the turn of the summer and autumn of 1989, which escapes from the disintegrating Yugoslavia in the 1990s, and others. The expression has been used in European politics and media since 2015 to increase previous names of the multiplied number of asylum seekers. He soon met with criticism because he ascribes a crisis to a group of people, not to the political treatment of them, and thus contextualizes the perception of the problem at the expense of the refugees. That is why the International Federation of Social Workers (IFSW) changed the expression Refugee Crisis in the title of its conference in March 2016 in Vienna to the Political Crisis Forcing People into Displacement and Refugee Status .

According to political scientist Julia Schulze Wessel, the “refugee crisis” can also be understood as the “refugee crisis”. Then the expression could point to the limitation of the previous term refugee, which does not capture the current causes of flight, and to the catastrophic situation of displaced persons , who mostly have to remain as internally displaced persons with no chance or protection or in camps or prisons, recently also in Europe. In fact, the term is used today in the context of negative consequences for the arrival and receiving countries. European and German politicians therefore usually only referred to the reduction in the number of refugees as the “solution to the refugee crisis”, not an improvement in the living conditions of refugees. The expression is therefore not consistent. The loss of control meant by the state could better be described as the “crisis of European refugee and migration policy”.

Social and political scientist Hannah von Grönheim criticizes the widespread terms "refugee crisis", "refugee problem" or "refugee problem" as "construction of a security requirement": The expressions suggest that Europe is threatened by refugees in order to avoid an already existing EU policy To legitimize and strengthen isolation and defense. Often the terms would be supplemented with expressions such as “drama” or (English) challenge , risk , large-scale humanitarian crisis , particularly strong and unforeseen pressure and with flood metaphors that acted as a dramatization. Politicians often linked the discourse about flight and migration directly with the discourse about European or national security needs and linguistically equated refugees and migrants with criminals. Von Grönheim referred to the anthropologist David Turton: He had already found in 2003 that Europeans often describe migration processes with flood metaphors and contrast refugees and immigrants with their own group (“they” versus “us”), even though their ancestors were migrants themselves. This is partly responsible for the fact that migration to Europe is perceived as something abnormal and migrants as a strange, threatening or even hostile group, excluded and dehumanized, with whose situation Europe historically has nothing to do.

"Migration crisis"

The term “Europe's migration crisis” is also used. Five migration researchers criticize the expression as ahistorical and narrowing: large-scale immigration is not historically new for Europe, the number of asylum seekers in summer 2015 was relatively low on a global scale and the mass exodus to southern European countries was predictable. The designation makes it easy to lose sight of the fact that this crisis was only one facet in a series of crises. This series actually began with the global financial crisis in 2007 , the consequences of which have already undermined social cohesion in Europe, revived right-wing populist forces and brought some illiberal governments in and outside Europe to power. The Arab Spring from 2011 was followed by the civil war in Syria since 2011 and the rise of the Islamic State , also because the international community was unable to resolve it . The EU's strict austerity policy contributed to the temporary collapse of the asylum systems in southern Europe and the humanitarian crises in Greece and along the Western Balkans route. It was only through the inability of the EU to manage arrivals via the Mediterranean routes that 2015 turned into a “migration crisis”. The sovereignty of the EU, weakened by going it alone, has encouraged further repressive policies and illiberal forces and thus caused a crisis for the entire EU. Other scholars and other experts on the subject describe the so-called refugee or migration crisis as one of many symptoms of a deep and persistent “solidarity crisis” across the EU that has affected refugees.

"Events of September 2015"

In September 2018, journalist Robin Alexander , author of the non-fiction bestseller Die Grittenen (2017), was interviewed by presenter Markus Lanz in his ZDF talk show of the same name about the third anniversary of the start of the refugee crisis. The Green politician Renate Künast interrupted the question with the objection that there had never been a refugee crisis. When Lanz suggested the term “migration crisis” as an alternative, Künast also disagreed, as the word “crisis” already had a negative connotation. From their point of view, those who use it run “the AfD's business”. Since Künast himself did not want to make a suggestion for a supposedly neutral term, the guests agreed to only speak of "the events of September 2015". However, since the term of the editorial appeared to be incomprehensible for viewers, the part of the discussion was cut out before the broadcast.

development

The refugee agency UNHCR registers people worldwide who are considered refugees according to the criteria of the Geneva Refugee Convention (GFK) of 1951, as well as internally displaced persons, war refugees, people forced to flee by environmental disasters and stateless people. Due to unreliable or missing information from many countries, the UNHCR only records part of the actual total. The vast majority of them have remained as internally displaced persons in their own country or in directly neighboring countries for decades. Only a small fraction of the refugees are state-registered asylum seekers . The UNHCR does not record refugee movements to Europe separately but as part of the global increase in the number of forcibly displaced people. Their number rose from 51.2 million (2013) through 60 (2014), 65.3 (2015) and 65.6 (2016) to 68.5 million by the end of 2017. Of these, 25.4 million were most recently registered Refugees. Only 2.643 million (10.4%) of them fled to or from Europe.

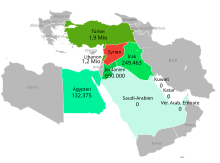

Countries of origin

In 2014, 53% of the UNHCR-registered displaced persons came from Syria , Afghanistan and Somalia . Larger proportions also came from Iraq , South Sudan , Nigeria , the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Ukraine . The Turkey , Pakistan , Iran and Lebanon (23.2% in relation to population) took world by far the most refugees. Between 2015 and 2016, Syrians made up almost a third of all asylum seekers in Europe, and Afghans and Iraqis together made up more than half.

| Country | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 14th | 15th | 7th |

| Albania | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Bangladesh | - | - | 3 |

| Ivory Coast | - | - | 2 |

| Eritrea | 3 | 3 | 4th |

| Guinea | - | - | 3 |

| Iraq | 10 | 11 | 7th |

| Iran | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Kosovo | 5 | - | - |

| Nigeria | 2 | 4th | 6th |

| Pakistan | 4th | 4th | 5 |

| Russia | - | 2 | |

| Syria | 29 | 28 | 16 |

| Turkey | - | - | 2 |

| Other | 26th | 28 | 40 |

Enter

For decades, the EU and the EU member states have made legal entry more and more difficult for refugees and those seeking protection, which has led to an ever increasing switch to unauthorized entry . They do not allow them to submit asylum applications in diplomatic missions of EU countries (embassy asylum) in their country of origin. War refugees from acute crisis regions also still need a visa to travel to the EU. In order to legally apply for asylum, most refugees are therefore forced to travel to Europe as so-called illegal migrants. Many come to Europe on a temporary visa and stay longer after their residence permit expires in order to go through an asylum procedure.

Refugees without a valid visa enter the EU via three main routes:

- the eastern Mediterranean route from Turkey to Greece, mostly by sea via the eastern Aegean Sea to Lesbos , more rarely by land to Bulgaria . From there they can travel via Romania or Serbia or the western Balkan route (Albania, Montenegro or North Macedonia ) to Hungary , Austria , Germany and, if necessary, further to western and northern Europe. In 2015, these routes were mainly used by Syrians, Afghans, Pakistanis and Sub-Saharan Africans, but also by North Africans from Tunisia and Morocco , for whom Turkey had waived the visa requirement in 2013.

- the central Mediterranean route from Libya to Italy ( Lampedusa , Sicily ) or Malta . In 2015, this route was mainly used by people from sub-Saharan Africa who came to the Mediterranean coast of North Africa via the Sahel zone . Syrians hardly used this route in 2015 because Egypt and Algeria had made it difficult for them to access Libya by requiring a visa.

- the western Mediterranean route from Morocco to Spain , either by sea or on the Spanish territory of Ceuta and Melilla . This escape route temporarily lost its importance due to the enormously increased border fences and border controls.

The EU border protection authority Frontex defines all these entries as illegal border crossings, regardless of the possible claim to asylum or protection of those who have entered and, according to their information, records them almost completely. It does not count illegal border crossings at internal European borders in order to exclude double counting and counting of intra-European migrant workers.

| year | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern Mediterranean route | 24,800 | 50,800 | 885,400 | 182,534 | 29,718 | 32,497 |

| Central Mediterranean route | 45,300 | 170,700 | 154,000 | 181.126 | 119,369 | 23,370 |

| Others | 8,600 | 9,300 | 10,000 | 10,658 | 18,738 | 58,569 |

| total | 78,700 | 230,800 | 1,049,400 | 374.318 | 172,301 | 138,882 |

As of December 2015, the EU registered around 913,000 irregular border crossings from Turkey to Greece. Almost 700,000 of them came to Central Europe via the Balkan route. After their closure and the EU-Turkey Agreement, 160,000 refugees arrived in Greece by July 2016, but only 2,000 of them in July. According to Frontex, almost two thirds fewer refugees came to the EU via the Mediterranean in 2016 than in 2015, but 20% more to Italy. In 2017, IOM counted 186,768 arrivals via the Mediterranean route. In the first half of 2018, Frontex counted 60,430 illegal border crossings (around half as many as in the first half of 2017), of which 16,100 went to Italy (81% fewer) and 14,700 to Spain (almost 100% more).

Fatalities

Neither the EU border surveillance systems (Frontex, Eurosur ) nor the EU states register the fatalities on the escape routes to Europe. Some NGOs counted the dead using different methods. The database project The Migrants' Files , which was run by journalists from major European newspapers until April 2014, collected and checked death and missing persons reports from government and media reports. According to this, 23,258 people died, drowned and / or were reported missing while fleeing to Europe from 2000 to 2013; at least 4000 more than previously assumed.

As of 2014, the International Organization for Migration (IOM), which works with UNHCR, took over the census of the dead. From January 2000 to June 30, 2017, the IOM recorded a total of 33,761 deaths or missing persons in the Mediterranean. From 2014 to the end of 2017, IOM registered more than 15,600 deaths in the Mediterranean and a further 6,042 deaths on land routes to and in Europe. Between 2014 and 2018, according to the IOM, an estimated 30,000 people disappeared while traveling through the Sahara desert . According to the IOM, at least twice as many migrants die in the Sahara desert as in the Mediterranean.

| year | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dead and missing | 3,303 | 3,919 | 5,143 | 3,235 | 2,297 |

According to UNHCR data, the proportion of those who died while crossing the Mediterranean rose from 1:38 in the first half of 2017 to 1:19 in the first half of 2018. In June 2018, Malta and Italy refused to allow private sea rescuers to call at their ports and confiscated some of their ships. After that the ratio increased to 1: 7. Although far fewer migrants than in the previous year used the central Mediterranean route, the proportion of fatalities increased sharply. As of August 3, the UNHCR registered 1,511 deaths, around 850 of them in June and July. It called the death rate "dramatic and extraordinary" and called on EU countries to guarantee the landing of migrants rescued from distress at sea.

The actual number of victims is estimated to be considerably higher, since many accidents and deaths are not observed, discovered and documented. In a single summer month of 2017, the sea rescue organization Sea-Eye found up to three capsized rubber dinghies with few or no bodies on the central Mediterranean route every day, without life jackets and other finders' markings. Based on the known occupancy of such boats with 150 to 200 people, the sea rescuer Johann Pätzold estimated the number of fatalities not found at more than 30,000 for 2017 alone. He wrote this in an open letter to the then Interior Minister Thomas de Maizière and Chancellor Angela Merkel . 2018 is underreporting of not found dead on the Mediterranean route up estimated to be four times as high as that of the reported deaths.

In addition, there are at least twice the estimated number of deaths and missing on the Sahara route. They perish there, also because the Niger government hardly provides any personnel or technology for search and rescue operations, but water points and villages in the desert have been militarily monitored under German and European pressure since 2016 and migrant transports have been punished with up to 30 years in prison.

Most of the dead are either nowhere to be found or cannot be identified. State authorities hardly care about the recovery and burial of the dead or the search for relatives; this is left to private initiatives. Examples of this kind of commitment can be found in Sfax and Zarzis , where a fisherman and a pastor, respectively, bury the dead washed up anonymously. On Lesbos, dead refugees were buried first in a soon-to-be-overcrowded poor cemetery, and since February 2016 in a new officially established cemetery.

Asylum applications

The number of refugees and migrants who entered Europe grew by around half in 2014, and in 2015 by more than double compared to the previous year. The number of registered asylum seekers is, however, an important indicator of the development, since many of those who have entered the country often applied for asylum for the first time in countries other than their arrival countries and were only recorded there.

| Country | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EU | 431.094 | 626.960 | 1,322,844 | 1,260,908 | 708.583 | 645.725 |

| Belgium | 21,029 | 22,710 | 44,662 | 18,278 | 18,342 | 22,530 |

| Bulgaria | 7.144 | 11,080 | 20,388 | 19,419 | 3,697 | 2,535 |

| Denmark | 7.169 | 14,680 | 20,937 | 6.178 | 3,220 | 3,570 |

| Germany | 126,705 | 202,645 | 476.508 | 745.154 | 222,562 | 184.180 |

| Estonia | 96 | 155 | 231 | 177 | 191 | 95 |

| Finland | 3,209 | 3,620 | 32,346 | 5,604 | 4,992 | 4,500 |

| France | 66,267 | 64,310 | 76.163 | 84,269 | 99,332 | 120,425 |

| Greece | 8,226 | 9,430 | 13.205 | 51,108 | 58,650 | 66,965 |

| Ireland | 946 | 1,450 | 3,276 | 2,244 | 2,930 | 3,670 |

| Italy | 26,620 | 64,625 | 83,540 | 122,959 | 128,848 | 59,950 |

| Croatia | 1,079 | 450 | 208 | 2.223 | 976 | 800 |

| Latvia | 193 | 375 | 330 | 351 | 357 | 185 |

| Lithuania | 399 | 440 | 317 | 432 | 543 | 405 |

| Luxembourg | 1,068 | 1,150 | 2,506 | 2.161 | 2,432 | 2,335 |

| Malta | 2,248 | 1,350 | 1,843 | 1.928 | 1,839 | 2.130 |

| Netherlands | 13,062 | 24,495 | 44,972 | 20,943 | 18,212 | 24,025 |

| Austria | 17,498 | 28,035 | 88,159 | 42,255 | 24,715 | 13,375 |

| Poland | 15,241 | 8,020 | 12,188 | 12.303 | 5,045 | 4.110 |

| Portugal | 502 | 440 | 895 | 1,462 | 1,752 | 1,285 |

| Romania | 1,493 | 1,545 | 1,260 | 1,882 | 4,817 | 2.135 |

| Sweden | 54,268 | 81,180 | 162,451 | 28,792 | 26,327 | 21,560 |

| Slovenia | 272 | 385 | 277 | 1,308 | 1,475 | 2,875 |

| Slovakia | 439 | 330 | 329 | 145 | 161 | 175 |

| Spain | 4,487 | 5,615 | 14,779 | 15,754 | 33,952 | 54,050 |

| Czech Republic | 694 | 1,145 | 1,515 | 1,473 | 1,445 | 1,690 |

| Hungary | 18,897 | 42,775 | 177.134 | 29,431 | 3,392 | 670 |

| United Kingdom | 30,586 | 32,785 | 40.159 | 39,737 | 33,781 | 37,730 |

| Cyprus | 1,257 | 1,745 | 2,266 | 2,938 | 4,598 | 7,765 |

| Non-members of the EU | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| Iceland | 127 | 170 | 369 | 1,124 | 1,085 | 775 |

| Liechtenstein | 54 | 65 | 150 | 81 | 149 | 165 |

| Norway | 11,931 | 11,415 | 31,112 | 3,487 | 3,519 | 2,660 |

| Switzerland | 21.304 | 23,555 | 39,446 | 27.141 | 18,013 | 15,160 |

From 2013 to 2014, first-time asylum applications in the EU rose by around 44%, the most in Italy (+ 143%), Hungary (+ 126%) and Denmark (+ 105%). At the same time, contrary to the trend, they decreased in Croatia (−58%), Poland, Malta, Slovakia, Portugal and France. Among the asylum seekers in Europe in 2015 were 88,300 unaccompanied minors .

State authorities often state the number of applications as evidence of disproportionate loads. However, the actual burdens only emerge from the consideration of the recognition rates, amounts and duration of deportation, naturalizations and relations to the number of inhabitants and average per capita income. An above-average number of asylum applications were made in eleven of the 28 EU countries, around a third of them in Germany. However, no European country was among the ten countries with the most asylum applications worldwide. In relation to the number of inhabitants, Sweden and Malta were in 9th and 10th place, Germany in 50th place in 2014. In relation to gross domestic product (GDP), 46 non-European countries, including some of the poorest countries in the world, took in more refugees than the EU countries. Germany was ranked 49th, in 2016 it was 63rd. In 2015, 2016 and 2017, asylum applications in the 28 EU countries and other European countries were distributed in per mille (per 1,000 inhabitants) as follows:

| Country | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|

| EU average | 2.47 | 2.36 | 1.27 |

| Belgium | 3.4 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Bulgaria | 2.8 | 2.6 | 0.4 |

| Denmark | 3.6 | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| Germany | 5.4 | 8.7 | 2.4 |

| Estonia | 1.7 | 1.1 | 1.3 |

| Finland | 5.8 | 0.9 | 0.7 |

| France | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.3 |

| Greece | 1.0 | 4.6 | 5.2 |

| Ireland | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| Italy | 1.3 | 1.9 | 2.0 |

| Croatia | 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| Latvia | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.18 |

| Lithuania | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.18 |

| Luxembourg | 4.1 | 3.5 | 3.9 |

| Malta | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.5 |

| Netherlands | 2.5 | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| Austria | 9.9 | 4.5 | 2.5 |

| Poland | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.07 |

| Portugal | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| Romania | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.2 |

| Sweden | 16.0 | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| Slovakia | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Slovenia | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| Spain | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Czech Republic | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Hungary | 17.7 | 2.8 | 0.3 |

| United Kingdom | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Cyprus | 2.4 | 3.3 | 5.2 |

| Iceland | - | 3.3 | - |

| Liechtenstein | - | 2.0 | - |

| Norway | 5.8 | 0.6 | - |

| Switzerland | 4.6 | 3.1 | - |

Causes of flight and handling of the crisis in the countries of origin

The European refugee crisis from 2015 is in the context of a global increase in the number of forcibly displaced persons. Migration research had predicted the increase for decades, citing population growth, economic inequality, low incomes, structural unemployment and protracted regional conflicts as contributing factors. According to Stefan Luft, acute violence against civilians by warring parties or paramilitary groups, including serious violations of human rights and international humanitarian law, as well as all kinds of persecution, economic and social impoverishment, man-made and natural disasters, climate change, and the consequences of Major projects or exploitation of natural resources. Today, many military groups use violence against individual population groups to destroy the rule of law and to create or maintain lawless conditions for undisturbed profit maximization.

The particular causes of the flight to Central Europe include the civil war in Syria , the advance and attacks of the Taliban in the context of the war in Afghanistan and the terrorist organization Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, humanitarian supply crises in Syria's neighboring states, armed conflicts and humanitarian crises in Somalia , Sudan, South Sudan, Eritrea, Nigeria, the war in Ukraine since 2014 as well as poverty and unemployment in many Western Balkan countries. The factors that gradually increased the flight to Central Europe include the collapse of “buffer states” such as Libya, the relative political stability in richer European countries and the temporary suspension of the Dublin rules in the EU.

The sharp increase in the summer of 2015 was largely due to acute supply bottlenecks in refugee camps around Syria: After states failed to keep their aid pledges to the UNHCR (Germany halved the relevant contributions in 2014), the UNHCR plan for Syrian refugees was set at 1.3 billion only 35% financed in spring 2015. As a result, the UNHCR had to cut the already modest payments to regional refugee camps, so that most of them went to neighboring countries. According to Paul Collier (economist) and Alexander Betts (migration researcher), the failure of the international community to provide the host states around Syria with adequate and timely aid has now (2017) been recognized as a grave moral and practical error.

On September 5, 2015, the German Chancellor decided, in consultation with the Hungarian and Austrian governments, to exceptionally allow refugees stuck or marching there to enter Germany without border controls, and assured Syrian civil war refugees a right to stay in Germany. TV reports and experience reports made the culture of welcome and recognition of many Germans known internationally. Political opponents presented the humanitarian exception as a personal invitation and the cause of the further increase in entries into the EU. Migration researcher Kirsten Hoesch, on the other hand, refers to a historically long-standing problem jam: legal entry routes and fair distribution of refugees in the EU are not least due to Germany's rejection failed. New armed conflicts had arisen in the last 15 years without existing conflicts having been resolved. For years, the richer states had provided insufficient aid to refugee camps, making living conditions there unsustainable. With globalization they would have opened their borders to capital and goods, but hardly to people outside the OECD . These have the digitization facilitates exchange of information on living conditions and opportunities in other states. "In addition to wars and conflicts, economic inequality is a main driver of international migration."

According to a study by the political scientist Arno Tausch (October 2015), the potential for “normal migration” from Arab and Muslim states, even without the civil war in Syria, comprised around 2.5 million Arabs and 6 million residents of the countries of Islamic cooperation . Angela Merkel underestimated this potential and largely redirected it to Europe through a "policy of invitation" in summer 2015.

Syria

In the civil war in Syria, all those involved committed serious war crimes and violations of human rights from the beginning (2011) . The Assad regime and up to 160 anti-government militias systematically cut off the population from supplies of food and medicine. Bombing attacks on residential areas, terrorist attacks, arbitrary arrests and torture became commonplace. There were also air strikes by the USA, Russia and Turkey, and indirect interventions by Iran and Saudi Arabia. By 2015 around 230,000 people were killed in the war. Over a million Syrians lost their houses and apartments. According to UNHCR, 12.2 million (almost 50% of the population) now needed survival aid; around eight million were displaced in the country, over four million (five million according to other information) had to leave it by 2015. Most Syrians have fled to neighboring Turkey since 2014. In 2015, the situation in the refugee camps in the Middle East (Syria, Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, Egypt) became life-threatening for 85% of those who had fled there. Loss of all savings, lack of work permits, food shortages and high prices left them with hunger, begging, indebtedness, violence, corruption and forced labor. The UNHCR relief plans were only 41% funded in 2015 because many states failed to keep their promises.

The UN's financial needs to supply the refugee camps in and around Syria managed by the UNHCR increased to 7.3 billion US dollars in 2016. The food rations in the refugee camps in Lebanon and Jordan were severely cut due to underfunding or failure to meet financial commitments.

In 2015, the Syrian government announced increased conscription to the Syrian armed forces , made it possible to buy oneself free from military service and made it easier to issue passports. This enabled opponents of the government and conscientious objectors to escape the civil war. It is believed that this is what the government intended. By April 2016, the fighting of all four major civil war parties around Aleppo caused an estimated 400,000 more people to flee to Turkey. After the Syrian government troops continued to gain ground, 28 lobby groups, aid and human rights organizations declared at the end of March 2017 that no one should be sent back to Syria at the moment, even if a region there seemed safe. The reasons for fleeing still exist. It is contrary to international law if a refugee is sent back against his will.

Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon

Iraq is considered a failed state as a result of three wars since 1980 and the civil war between 2003 and 2011. Since 2014, eight million Iraqis have again needed humanitarian aid, especially in the non-government-controlled north and west. Around seven million people lack medical care, clean water and sanitary facilities. Around three million (50% of them children) have been displaced in Iraq since 2014, for example by the Islamic State . At the same time, around 250,000 Syrians fled to Iraq. In autumn 2016, the battle for Mosul sparked further flight. The UNHCR estimated that around a million residents could be displaced.

In Jordan, the situation for Syrian refugees deteriorated significantly in 2015. Many only have the clothes that they wear. Power outages, water shortages, and expensive fees for visits to the doctor are an additional burden. 58% of the chronically ill no longer receive medical care. Competition in the labor market exacerbates tensions with Jordanians.

The Lebanon has four million inhabitants, granted in 2015 about one million registered refugees and asylum counted in 2016 with the arrival of a further million unregistered asylum seekers. At the UN refugee conference in Geneva at the end of March 2016, the government feared that this burden could lead to the collapse of the state. In 2015, it banned the UNHCR from registering new refugees, banned them from working, made access to camps more difficult, made residence permits, which had to be renewed annually, more expensive, required certified rental certificates and expensive health certificates. Many live in a confined space in a vulnerable position. 39% do not have clean drinking water. The state offers Syrian children free schooling, but around 20% have to drop out to earn a living. There is no access to vocational training. Many girls get into forced marriages or prostitution. 41% of Syrians live illegally in the country, many only cross it when fleeing to Turkey.

Afghanistan

In Afghanistan there has been almost uninterrupted war and civil war since 1980, so that around half of the population has left the country since then. Since the NATO- led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) expired in 2014, the number of civilians killed and injured (including many children) has risen sharply again. The Taliban and other armed Islamists are carrying out attacks. Humanitarian workers are also attacked, and their organizations fail to reach many regions of the country. In 2014, the second most refugees worldwide came from Afghanistan.

In 2015, the Taliban captured many more district centers. According to the UN, around 6.3 million Afghans were affected by fighting, and almost 196,000 people fled. At the beginning of 2016, the Afghan refugee minister Hossain Alemi Balkhi declared 31 of his country's 34 provinces to be too unsafe to carry out repatriations of the elderly, the sick and children.

In June 2016, Amnesty International and the UN estimated the number of internally displaced persons in Afghanistan at almost 1.2 million. Aid from the West has decreased significantly 15 years after the start of the war in Afghanistan . The neighboring states of Pakistan and Iran together are home to more than three million Afghans. According to a report by special instructor John Sopko in the US Senate, the Afghan government only controlled 233 (57.2%) of the 407 districts in mid-November 2016. 41 districts were in the hands of the Taliban, 133 districts were contested. About 9.2 million Afghans lived in the contested areas.

Pakistan

In parts of Pakistan , there is an internal conflict between the government and militant insurgents, including the Taliban, who control parts of the state's territory. In addition, the country was repeatedly hit by natural disasters (e.g. flood disaster in 2010 ). In addition, there is daily violence against women and religious minorities (such as Hindus, Sikhs, Christians and the Ahmadiyya ).

Since the beginning of November, Pakistan has refused to take back deported Pakistani refugees and has banned aircraft with refugees on board, with the exception of aircraft from Great Britain, from landing. Interior Minister Ali Khan justified the suspension of the existing readmission agreement on the claim that the European states schöben Pakistanis, because there lightly, insinuating them a terrorist background.

Sub-Saharan Africa

In Sub-Saharan Africa , around four million internally displaced persons have fled their regions of origin because of humanitarian emergencies and armed conflicts, mainly from Somalia, Sudan , South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Central African Republic . In the decades-long Somali civil war , all parties to the conflict (government troops, Islamist terrorist militia Al-Shabaab and the African Union ) commit serious human rights violations, kidnap, torture, rape and forcibly recruit people, including children as child soldiers . According to AI, over a million people were displaced from Somalia in 2014. 2.1 million need humanitarian aid, 100,000 civilians were injured or killed. A prolonged drought and blockades in aid supplies and access to those in need made the situation worse. The UN classifies the humanitarian crisis in Somalia as the worst in the world. Only the autonomous regions of Puntland and Somaliland in the north were considered relatively stable.

The civil war in southern Sudan since 2013 sales according to the UN about two million Sudanese, of which 500,000 in neighboring countries. Four million suffer from acute food shortages. 400,000 children are no longer allowed to attend school, and 70% of schools in contested areas have had to close. According to AI, all warring parties completely disregard human rights, also because there is no accountability. Eritrea is a military dictatorship with a planned economy and one-party regime and is one of the poorest countries in the world. The UN registers ongoing systematic violations of human rights in Eritrea . In 2014 around 340,000 Eritreans fled the country.

By 2016, over a million Eritreans had fled, although it is forbidden to flee from the country and soldiers with orders to shoot are guarding the borders. Around 28 criminal gangs of people smuggled the route between them and brought migrants for set prices (around 4,000 US dollars at the time) initially to Khartoum , for a further 3,000 dollars by delivery truck through the desert to the coast in Libya; the crossing costs another $ 3,000. Often they leave migrants to their own devices in Eastern Sudan, where armed gangs kidnap them, torture them for weeks and systematically extort high ransom money from their relatives (~ US $ 15,000 per person). Those who are not ransomed are either left disoriented in the desert or killed. The authorities of Sudan do not take action against the gang leaders they know because they benefit from them themselves. The business with migrants, along with drug and arms trafficking, has become the most profitable branch of the economy in Central Africa since the EU closed itself tightly and prevented legal entry. The main reasons given are unsatisfactory future prospects, unlimited military service, fear of arbitrary arrest or prison terms. Every Eritrean who now lives abroad has to pay a "development tax" of 2% of his gross income to the state retroactively from the date of departure.

Nigeria is one of the countries with the highest population growth in the world. Only a few benefit from the country's wealth of resources ( oil ) and the relatively high economic output; Corruption is widespread. The Islamist terrorist group Boko Haram is active in northern Nigeria, and its attacks and the government's response to them killed over 14,000 people between 2009 and 2014. In 2014, 6347 civilian deaths were counted.

In Niger , 10,500 people are on the urgency list for resettlement in the EU, in the central African state of Chad 83,500. In the past few years only 756 have been resettled in Canada and the USA, none in Europe.

In the Sahara in 2019, the small local private initiative Alarmphone-Sahara, which it claims to be dependent on support, offered help for people in need locally.

Maghreb states

In 2015, more refugees came from the Maghreb countries of Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia than before via the eastern Mediterranean route to Europe. According to Pro Asyl, the reasons for fleeing are poverty, high unemployment, a lack of freedom of the press, persecution of minorities, arbitrary detention and abuse. In the democracy index 2014 calculated by the business magazine The Economist , Algeria and Morocco are classified as authoritarian regimes .

According to Amnesty International (January 2016), an estimated 50% of young academics are unemployed; therefore, many people left Morocco. Algeria is suffering from the consequences of the Algerian civil war , low oil prices and the poor economic situation. In addition, dissidents and homosexuals are persecuted in both states.

In the summer of 2017, significantly more people from Morocco took boats to Spain than in the previous year. Frontex attributed the increase to growing instability in some countries of origin and transit and to the dismantling of some refugee camps in Morocco and Algeria. The majority of those arriving in Spain, according to a spokesman for the Red Cross in the province of Cadiz , come from Morocco and most of them are fleeing the unrest in the Rif Mountains . According to media reports, the protests in the Berber region of the Rif Mountains are "the worst unrest since the Arab Spring 2011". The correspondent Alexander Gschwind reported that the government under Mohammed VI. have announced new flows of refugees across the Strait of Gibraltar in the event that they are prevented from "restoring order" in the Rif. Gschwind saw this as a threat from the Moroccan government to Spain and Brussels.

Libya

After the civil war of 2011 , which ended with the overthrow of the dictator Muammar al-Gaddafi , Libya fell apart and was deeply divided. Large parts of the country are still ruled by various militias who fight each other. The collapse of the state opened new routes to Europe for refugees. In addition, thousands of Africans who had previously lived in Libya as migrant workers came to Italy as refugees via the Mediterranean route.

In autumn 2014, during the second civil war , Islamist militias drove the previously internationally recognized council of deputies to Tobruk and formed the New General National Congress (NGNC) in Tripoli . Both parties rejected a proposal by the UN to share government power in order to receive more aid for reconstruction and the fight against migration. In early November 2015, the NGNC threatened to rent ships and flood Europe with hundreds of thousands of migrants if the EU did not recognize it as the legitimate government of Libya. His representative pointed to costly measures against migrant crossings, including coastal surveillance, prison centers, feeding the captured migrants, and return programs. According to Libyan sources, around 8,000 militiamen were fighting people smuggling and illegal entry into Libya. Small patrols monitored the ports and collected bodies of drowned migrants. The Coast Guard brought captured migrants to Tripoli to collective prisons. Congress refused to increase staff because of the instability of the government and saw migration prevention as more of a problem for Europe. German diplomats described the conditions in Libyan refugee camps as " similar to concentration camps ".

A unity government mediated by the UN in December 2015, the Government of National Accord (GNA) under Fayiz al-Sarradsch , with a High Council of State appointed by the NGNC as the second chamber alongside the Council of Representatives, was unable to resolve the conflict. The council of deputies in Tobruk, with Khalifa Haftar as military leader, did not recognize the GNA, while various militias, including IS units, fought each other in Tripoli and other parts of the country.

In June 2018, the UN Security Council announced sanctions against six leaders of smuggling networks in Libya, of which Ermias Ghermay is considered the most important, and Abd Al Rahman al-Milad, who heads the coast guard in the Zawiya section and is said to be smuggling people himself. This decision was also a response to the global outrage that media reports sparked in late 2017. Among other things, film recordings by CNN from Libya had shown a slave market at which migrants were auctioned.

In Bani Walid , which is the place of residence for sub-Saharan migrants on their way to Europe and for their people smugglers , there is (as of 2019) a private aid initiative.

At the turn of the year 2019/2020, the persistently poor humanitarian situation threatened to worsen due to the ongoing civil war.

Turkey

Turkey has been the main transit country for Syrian and other refugees since 2011. Around 100,000 Syrians had already fled there in 2012; in August 2014 their number rose to around 1.4 million, and by November 2015 to over two million. According to Human Rights Watch , Turkey has only allowed refugees to enter in exceptional cases since March 2015. More than 600,000 refugees left Turkey for Europe in 2015. The migration researcher Murat Erdogan said that “many refugees who statistically continue to appear in Turkey have long been in Europe.” In September 2015, several thousand refugees attempted to collectively cross the Turkish-Greek or Turkish-Bulgarian land border from Istanbul , but were stopped by the Turkish police in Edirne . It is not known how many Syrians were still in Turkey at the beginning of March 2016. The Turkish government stated 2.7 million, but only 270,000 of them were camp residents. It is not known how many have left Turkey for Europe. The UNHCR registered a total of 5.52 million Syrian refugees from 2013 to the beginning of 2018, of which 1.46 million in Turkey, 997,552 in Lebanon, 655,524 in Jordan, 254,057 in Egypt, 126,688 in Egypt, 30,104 in Libya. Some Arab states also took in Syrian refugees, but gave them little financial support. There was a lack of resources in the UN refugee camps. More and more of the camp residents tried to get to Europe.

According to its own information, the United Nations World Food Program was only able to provide around 154,000 refugees in Turkey with food in the summer of 2015. According to its government, Turkey had spent seven billion euros on the accommodation and care of refugees by the end of 2015. However, most of the Syrian refugees did not receive any financial support and were not allowed to work legally in Turkey. In October 2015, the Greek authorities suspected Turkey of deliberately accelerating the refugee movement in order to obtain aid funds and visa relief for Turks from the EU. In addition, in 2014 Turkey only approved six of 9,000 Greek take-back requests, despite a return agreement with Greece.

According to the UNHCR, there were around 5.6 million war refugees in Syria's neighboring countries in September 2018, including more than 3.6 million in Turkey. Around 360,000 of the refugees and asylum seekers living in Turkey come from countries other than Syria, mainly Afghanistan , Iraq and Iran .

Bangladesh

In Bangladesh there is often violence against religious minorities and against women. In addition, there have been increasing attacks on secularists and members of religious minorities in Bangladesh since 2013 . In the first three months of 2016, only one person from Bangladesh was registered in Italy. Since 2017 people smugglers in Libya began to network better internationally. From January to March 2017, 2,831 registered refugees from Bangladesh came to Italy.

Russia and Ukraine

As a result of the war in Ukraine since 2014 , one million people are dependent on humanitarian aid such as shelter, food and medicine. 1.3 million were internally displaced in May 2015. 860,000 Ukrainians (33% of them children) fled to neighboring countries. The unstable security situation, destroyed infrastructure and bureaucratic obstacles make access difficult for aid organizations. Against the background of the human rights situation in Russia, there are still asylum-seeking Russian citizens.

Western Balkans

Most of the refugees within Europe came from the Western Balkans during the breakup process of Yugoslavia in the 1990s. The existing migration networks and the visa exemption for most of the Western Balkans, which was introduced in 2009/2010, caused a renewed increase in immigration to Central Europe. The push factors include the consequences of civil wars, high unemployment , impoverishment, lack of educational opportunities, weak social and health systems, corruption , nepotism , discrimination and persecution of minorities such as the Roma . From 2012 to 2015, 58% of asylum seekers from the Western Balkans submitted their applications in Germany.

According to the World Bank , one third of the population in Kosovo lives in existential poverty. Other reasons for fleeing are the shadow economy , organized crime and ethnic tensions (especially antiziganism against the Roma). In Albania, the common law of Kanun , blood vengeance , vigilante justice and violence against women also prevail .

Germany, Austria and Switzerland regard Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia and Serbia as safe countries of origin , and since October 24, 2015 Germany has also considered Kosovo and Montenegro.

EU migration policy

Dublin procedure

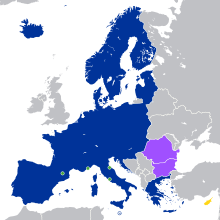

EU policy should balance the economic interest in the smoothest possible international trade and mobility with the interest in controlling and managing migration. For this, the EU Commission decided in the summer of 2013. Common European Asylum System (CEAS) with five revised guidelines: the Asylum Procedures Directive , the Qualification Directive , the Reception Conditions Directive , the Dublin III Regulation and the Eurodac Regulations . The CEAS decision emphasizes the shared responsibility of the EU states to guarantee the fundamental right to asylum according to uniform standards and procedures in order to reduce the unequal treatment of asylum seekers and to avoid shifting the asylum procedure to other EU states. These problems arose from contradictions between the dismantling of border controls in the Schengen area on the one hand and the obligation to accept first-time applicants on the other. In order to compensate for the opening of internal borders, the EU's external borders should be more strongly secured, more illegal entry into the EU should be prevented and asylum seekers who have entered EU territory should be better protected on a humanitarian basis. Standardized procedures and social benefits for asylum seekers were largely missed, however, as the density of rules is too complex and leaves too much scope for discretion. The migration of many asylum seekers to other EU countries could not be prevented either. Before and during the refugee crisis, there were many national solo efforts that undermined and endangered the legal standards already achieved.

According to the Dublin Convention of 1990, the state where a refugee first reaches Europe should register him and carry out his asylum procedure. That is why the southern European border states Greece and Italy had to take in the vast majority of incoming refugees. Even before the crisis, they allowed unregistered refugees to travel on to Central Europe ("wave them through") because the EU, including Germany, had blocked a fair distribution key until 2015. The Dublin III regulation of 2013, which came into force in 2015, only regulates responsibility for asylum procedures, not the Europe-wide distribution of asylum seekers. Due to the high number of refugees arriving, most of whom wanted to apply for asylum in other countries, and the lack of reception capacities, the border states responsible only registered some of them in the summer of 2015 and mostly allowed them to continue their journey directly. Other EU countries along the Western Balkans route then initially suspended border controls. The mandatory return transfers also only took place to a limited extent. The Dublin rules proved impracticable in this situation.

After the decline in the number of immigrants, the EU Commission recommended on December 8, 2016 that the asylum procedures should be carried out again in the countries of the asylum seekers' first entry in accordance with the Dublin rules from March 15, 2017. According to EU Migration Commissioner Dimitris Avramopoulos, “vulnerable” and underage asylum seekers should not be sent back there. The regulation should only apply to asylum seekers arriving in the future. The authorities and courts of the EU states would have to make a final decision.

In November 2017, the European Parliament proposed some changes to the EU Commission's draft law on Dublin reform. According to this, the EU state in which relatives of an asylum seeker live should possibly carry out the asylum procedure, and the family term in the asylum qualification directive should be extended to more distant relatives. Because asylum seekers traveled to their relatives anyway, families could also be brought together right away, thus saving procedural costs. States with external EU borders should remain responsible for security checks and prevent obvious economic refugees from continuing their journey. German government representatives feared, however, that in future it would be sufficient to simply claim a relationship. This will significantly expand family reunification to Germany. The European Council must reject the proposals. The parliamentary proposal did not provide for a punishment for asylum seekers who, after being assigned to one EU country, travel on to another.

Border security

The Schengen Borders Code (SGK, 2006) and the Schengen Information System (SIS, 2013) enable uniform visas for the Schengen area, searches, acquisition and exchange of biometric data. 90% of the accesses to the SIS database served to refuse entry to foreigners from third countries. The SGK amendment of 2013 allows border controls in the Schengen area limited to six months in defined exceptional cases, checked by EU bodies, of a “serious threat to public order” or if other EU states do not adequately secure their borders. On September 13, 2015, Germany introduced temporary identity checks at the border with Austria in order to register refugees upon entry. Federal Minister of the Interior Thomas de Maizière named urgent “security reasons” in order to regain “an orderly procedure” upon entry. The EU Commission legitimized the measure for an initial ten days, but warned of a domino effect. Shortly afterwards, Austria, Slovakia and the Netherlands also announced temporary border controls. Since March 2016, the 28 EU states have applied the SGK again to end the “irregular flow of migrants” on the Balkan route. On September 16, their heads of government called for the exclusion of uncontrolled migration flows, complete control of the external borders, a return to Schengen and a long-term joint migration policy characterized by responsibility and solidarity in the “ Bratislava Roadmap ”. On February 1, 2017, the EU Commission recommended that controls at certain internal borders be continued in order to preserve the Schengen area as a whole. Despite the decline in new arrivals, there is still considerable migratory pressure at the EU's external borders and many migrants are still in Greece. On May 2, 2017, the EU allowed border controls to be extended by six months; further extensions are illegal.

Between 2003 and 2010, the EU granted Morocco almost EUR 68 million in loans to secure borders. Spain had military barriers built around Ceuta and Melilla before 2015. Police patrols forcibly repel anyone who overcomes a fence there and applies for asylum. Greece and Bulgaria built walls and fences on their mainland borders with Turkey, Hungary from June 2015 border facilities on the border with Serbia and Croatia , Slovenia on the border with Croatia, Austria on the border with Slovenia, North Macedonia from November 2015 on the border with Greece. All new border installations are intended to prevent illegal crossings and facilitate controls at designated crossings, but have already been overcome by migrants. They are criticized for lack of effectiveness and incorrect prioritization. In 2015, Austria and Germany supplied surveillance technology to North Macedonia, Austria, Slovakia, the Czech Republic and Hungary also sent police officers there. In September 2017, the Hungarian government demanded half the costs (440 million euros) of the border construction from the EU, which the EU rejected.

From the summer of 2015, refugees often ran into police officers, especially at border crossings on the Balkan route and already in Turkey. In September 2015, many refugees walked from Istanbul to the Bulgarian border, 250 km away, and demanded legal access to EU territory in order not to risk their lives when crossing the sea. The Turkish police broke up a refugee camp near Edirne with tear gas and batons. Most of the camp residents returned after days of street fighting.

In 2004, the EU created the Frontex agency to protect its external borders more effectively, while preserving national sovereignty over border protection. Initially, Frontex was not a border police and was supposed to support the EU states with risk analyzes, information exchange, training of border officials and support staff in border protection and collective returns. Since 2006, your budget has increased from 19 million to 114 million euros per year. Frontex has emergency response teams to counter a “massive influx of third-country nationals”. Above all, they prevented boat refugees from reaching Europe, pushed them back and thus collectively prevented the filing of asylum applications. In doing so, they broke the principle of non-refoulement of the CSF (Article 33). That is why the EU Council committed Frontex in 2011 with an amendment to the founding regulation to comply with the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, the EU and the GRC. A fundamental rights officer should ensure this compliance. From January 2016, the EU wanted to upgrade Frontex to an independent police unit, initially in North Macedonia and then in particular to protect the Greek EU external border.

In September 2015, the German embassy in Kabul (Afghanistan) saw signs that the Afghan government had issued one million passports to travel to Europe. On December 20, 2015, Frontex head Fabrice Leggeri declared the “large flows of people who are currently entering Europe uncontrolled” a security risk. Terrorists could impersonate refugees and smuggle in with forged or machine-made passports. He referred to lists of serial numbers of lost passports from Syria and Iraq, which European authorities can use to detect forged passports. German police union representatives criticized the fact that not all refugees who entered Germany had their fingerprints taken and that not all of them had been recorded by the identification service. In hundreds of thousands of cases, the border guards on the German-Austrian border do not know who entered under what name and why. These conditions are "dangerous to the state". The security authorities in Europe cannot access fingerprint data of refugees in June 2017. There was a lack of uniform standards for the asylum procedure and rules to prevent recognized asylum seekers from moving to other EU countries.

Closure of the Balkan route and consequences

In the summer of 2015, the situation on the Western Balkans route worsened. Several thousand people passed through North Macedonia and Serbia every day, up to July a total of over 100,000. Hungary started building the border fence with Serbia. Both states were organizationally and economically overwhelmed. The humanitarian conditions were catastrophic; Refugees waited for escape helpers at illegal assembly points without any infrastructure.

On October 25, 2015, the heads of state and government of ten EU countries as well as Serbia, Albania and North Macedonia decided at a special summit on a 17-point plan for immediate measures to reduce the number of refugees on the Balkan route: 100,000 new reception places for refugees should be on the Balkan route created, of which 50,000 in Greece. 400 border guards should be dispatched to Slovenia within a week to relieve the burden. Frontex should better secure the border between Greece, North Macedonia, Albania and Serbia. A network of contact persons at the highest level should be created within 24 hours in order to achieve “a gradual, controlled and orderly movement” of the refugees on the Balkan route. Newcomers should be registered biometrically in the countries of first reception . Refugees who are not entitled to protection should be deported to their country of origin as soon as possible. Refugees should not be led to another state's border without the consent of another state.

During the “ Brexit ” negotiations on February 19, 2016, the Greek head of state demanded that the resolutions only be approved if the Balkan route remained open. On February 22, 2016, the Greek Vice Minister Ioannis Mouzalas said that the heads of state had agreed at the EU summit to keep the Balkan route open to Iraqis, Syrians and Afghans until March. Austria's Interior Minister confirmed that Germany had promised Greece a continuation of the “policy of open borders”.

On the initiative of Austria, a Western Balkans conference to reduce the number of refugees along the Balkan route was held in Vienna on February 24, 2016 . Greece was not invited. The conference participants agreed to alternately send police officers to control particularly affected border areas and to standardize the criteria for the registration and rejection of refugees. Austria, Slovenia, Hungary, Croatia, Serbia and North Macedonia closed their borders to almost all refugees who tried to immigrate via the western Balkan route. This caused a backlog in Greece and exacerbated the sometimes chaotic conditions there. The measures were planned as a "desired chain reaction of reason" to put the EU Commission and Greece under pressure and to reduce the number of asylum seekers in Austria. According to a Frontex report, the number of refugees on the Balkan route fell in spring 2016, mainly because of this. According to Austria's Foreign Minister at the time, Sebastian Kurz , there was “massive resistance” to the route being closed during the planning phase. In retrospect (May 2016), the step is correct and has now also been recognized as effective. It was “not going it alone, but a regional measure” as a result of “massive excessive demands”. North Macedonia in particular has taken on a very difficult task without benefiting from it itself. Positive consequences for Germany would have to be assessed there. The EU refused to close.

When North Macedonia closed its border with Greece at the end of February 2016 and, like other Balkan states, only allowed a few daily border crossings, around 8,500 Syrians and Iraqis were stranded in the Idomeni camp with the prospect of protection status . Because this only had space for a maximum of 2,500 people, a few hundred residents broke through Greek police chains and pried open a border gate. Macedonian police used tear gas against them; some migrants responded by throwing stones. Because of the feared border closure, many newcomers had rushed through Greece to the Macedonian border. The attempt to storm the border followed a rumor that the Macedonian border was open again. Arson attacks were carried out on newly built camps in northern Greece.

As early as 2015, Human Rights Watch recorded a lot of evidence and testimony of border guards violating the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. Afterwards, Croatian police immediately pushed asylum seekers back to Serbia unchecked, often stealing their money, destroying their smartphones and abusing those affected. Serbia did not accommodate those who had been rejected in a humane manner, so that children also had to spend the night outdoors. After the closure of the Balkan route, many smaller refugee camps were set up at the EU's external borders (such as Šid in Serbia), whose residents are mostly minors, have been walking for years and receive no state aid. They are exposed to the cold, lack of water, poor hygiene, infections and almost daily abuse by the border police in Hungary, Croatia and Bulgaria. 92% of the children and adolescents who received psychosocial help from Doctors Without Borders up to July 2017 reported deliberate police violence. By then, volunteer associations had documented 86 cases, including bite wounds from police dogs, severe bruises, injuries from pepper spray or tasers. According to Pro Asyl , states have effectively suspended European asylum law at these borders. Closing the Balkan route also strengthened gangs of smugglers and gangs. Only civil society engagement, not the EU, prevents humanitarian disasters in the refugee shelters.

Fight against human smugglers and rescue at sea

In the course of the refugee crisis, criminal networks of people smugglers emerged who sell refugees for large sums of money logistical aid for illegal border crossings, entry and residence. After many migrant families have sold all their property and gone into debt, migrants often do everything in their power not to have to turn back unsuccessfully. Organized smuggling networks are profit-oriented, use the dependency on migrants to increase sales and often put their lives at risk. The transitions to human trafficking are fluid, as smugglers-dependent customers can be easily defrauded, deprived of their funds, exploited, forced into prostitution and drug trafficking, or sold as slaves.

On the central Mediterranean route smuggle smugglers or tractor refugees often in small, overcrowded boats with just enough fuel from the Libyan territorial waters. After leaving the twelve-mile zone, many of them send an emergency call to the EU naval mission “Sophia” , whose ships are obliged by the international law of the sea to rescue them from the twelve-mile zone. Since September 2015, 13,000 refugees have been brought to EU territory in this way. Many of the unseaworthy and overloaded boats capsize, so that many people drown before they can be rescued.

After the two boat accidents off Lampedusa at the beginning of October 2013 (more than 600 deaths in total), the Italian Navy and Coast Guard expanded the ongoing surveillance operation Constant Vigilance in the Strait of Sicily into Operation Mare Nostrum , which was five times larger , and presented it as a humanitarian sea rescue operation. She saved around 150,000 people. Italy ended it after a year because the EU did not want to bear the costs (around 10 million euros per month). It was replaced by the Frontex Operation Triton , the goals and means of which were much more limited: it was supposed to work with the military and border protection authorities in the Mediterranean region, rescue refugees from distress in coastal waters, above all fight smugglers at sea and on land directly and destroy their transport boats.

In 2015, according to Europol, 90% of 1.2 million illegal border crossings took place with the support of smugglers. They earned an estimated three to six billion euros from it. Europol has set up a new center to combat people smuggling . In 2016, Europol identified people smuggling as the fastest growing criminal market in Europe. On EU decision of 18./19. In February 2016, a German-led NATO naval unit in the Aegean is expected to deliver results of reconnaissance to combat people smugglers. Four ships of the Standing NATO Maritime Group 2 report suspicious ship movements to the coast guards of Greece and Turkey. The crews are not allowed to stop refugee boats, but rescue refugees from distress at sea and bring them back to Turkey. which was later put into perspective. To reduce the number of refugees in the EU, Libya would have to allow EU-commanded warships to take action against smugglers directly in its territorial waters.

In June 2016, the EU Council decided to help build the Libyan coast guard's capacities against smugglers and for search and rescue operations.

According to the UN, 99,846 people were rescued from refugee boats from January 1 to September 3, 2017. From August 2017, the number fell sharply because the Libyan coast guard and the Italian navy stopped refugee boats and brought the passengers back to Libya. On August 10, the Libyan government declared its own rescue zone outside its own territorial waters and forbade NGOs to enter it without its permission. With Italian help, she also hired militias to interrupt the overland transport of refugees to Libya. The Libyan Coast Guard repeatedly shot at rescuers' ships to drive them away and intimidate them. Some experts criticized that this would lead to more deaths and violate the international law obligation to rescue at sea and to ensure free shipping.

In the summer of 2014, UN Commissioner for Refugees António Guterres asked the EU to take in more refugees from Syria, demanded legal entry routes and registration centers and warned against uncontrolled entry into Europe with the help of smugglers. EU representatives and authorities responsible for EU external borders such as Frontex assign the main blame for the deaths in the Mediterranean to the smugglers: They would use more and more unseaworthy boats out of greed for profit. The migration researcher Klaus Jürgen Bade , on the other hand, criticizes that the ongoing mass deaths in the Mediterranean are a consequence of EU migration policy: This lacks a sustainable and coherent immigration concept. It offers migrants from war and poverty regions hardly any legal access routes to Europe and only relies on their deterrence. In its increasingly effective defense measures against asylum seekers, refugees and other unwanted immigrants, the EU is accepting the death rates at its external borders. Nobody should accuse the EU of failing to provide assistance, but it is politically calculating the current death because it is overriding border security to sea rescue. He referred to SZ editor Heribert Prantl , who described the mass deaths of refugees after the boat accident off Lampedusa (2013) as “part of the EU's deterrent strategy”. Humanitarian organizations also criticize the EU's policy of isolation and demand safe escape corridors as well as a sea rescue coordinated and adequately equipped by the EU. The SZ commentator Andrea Bachstein fears that escape corridors could act as an “invitation to the greatest possible mass migration from the poor regions of the world”. Some humanitarian organizations criticize the fact that the Frontex contract, which is limited to smugglers near the coast, amounts to a fight against refugees. They also reject the rejection of refugees to Libya because of the serious human rights violations there, especially in refugee camps. According to Amnesty International , the conditions in Libya are characterized by unimaginable violence and hopelessness. AI therefore recommends an evacuation of all refugees imprisoned there.

Agreement with Turkey

In November 2015, the German federal government assigned Turkey a key role in dealing with the refugee crisis. For more cooperation in securing the EU's external borders, Chancellor Angela Merkel promised Turkey that it would make travel easier for its citizens, more money for refugee camps and a new dynamic in Turkey's accession negotiations with the European Union . Turkey asked the EU for a return agreement and a visa exemption for the Schengen area from July 2016.

The “hotspots” concept should be implemented by the end of November 2015. In return for Turkish reception camps, Turkey demanded that the EU support a militarily secured buffer and no-fly zone in northern Syria in order to prevent the Kurdish militias fighting against IS from expanding there and to enable Turkey to return around two million refugees to Syria . The EU and Turkey had agreed to pay three billion euros for two years. In November 2015, Erdogan instead demanded three billion euros per year. On November 30, 2015, the EU and Turkey agreed an action plan to limit immigration to the EU via Turkey. Whether this plan reduced the influx of refugees to Europe is controversial: While the EU Commission found a decrease of more than 50% in one week, according to the UNHCR the influx rose by 36% that week. At the turn of the year 2015-2016, government agencies in Greece continued to count up to 4,000 arrivals a day despite bad weather and heavy seas. They blamed Turkey for it. At the beginning of January 2016, the Bavarian Minister of the Interior identified around 3,000 refugees arriving every day.

On December 17, 2015, ten EU states agreed with Turkey on a “contingent plan” for the resettlement of refugees. Eleven EU countries, including Germany and Austria, wanted to take in refugees directly from Turkey; all 28 EU members could take part. Some Eastern European EU states, however, refused to accept Muslims on principle. The size of the refugee contingents was not disclosed. The Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu called for it to be measured generously. Resettlement should begin with Syrians.

From January 8, 2016, Syrians in Turkey were required to have a visa because, according to the Turkish government, more and more people with forged Syrian passports were entering the country via Egypt and Lebanon. At the same time, Syrian refugees in Turkey received work permits, free health care and schooling. A particularly large number of them moved to Gaziantep near the Syrian border, where there was a high demand for labor due to the booming export industries. After tens of thousands of Syrians fled the Aleppo region in February 2016, Turkey closed its borders and tried to help people in Syria together with aid organizations. At the same time, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan threatened that if the EU did not support Turkey more generously, its western borders would be opened.

The relocation concept was negotiated again at the EU-Turkey summit in early March 2016. The direct transport of refugees from Turkish camps to EU countries should curb the smuggling crime and reduce risky crossings to Greece. Human rights activists emphasized that the collective deportation of boat refugees to Turkey without individual assessment contradicts applicable international and European law, as does the deportation of non-Syrian refugees from Turkey to countries of origin that violate human rights or wage war. Politicians and human rights activists feared that concessions to Turkey would weaken the EU and strengthen Erdogan's autocratic rule.

On March 18, 2016, the European Council unanimously put the EU-Turkey Agreement into effect. This increased the EU aid funds by three to six billion euros and agreed to accelerate their disbursement. The EU has now transferred parts of the funds that had been promised for refugee aid projects in Turkey. The latter undertook to take back all persons who entered Greece illegally from now on, while the EU allowed legal asylum seekers to enter or relocate from Turkey. A refugee can only stay in Greece if he can prove that he is being persecuted in Turkey. That should cut human traffickers and smugglers' business foundation. Turkish citizens should be granted visa waiver to travel to the EU if Turkey met a number of conditions. After April 4, the resettlement of a maximum of 72,000 civil war refugees from Turkey to Europe began. These conditions are not met as of November 2018.

According to data from the EU Commission, since the contract was signed by the end of 2017, 35,000 and by January 2018 62,190 refugees from Turkey had entered Greek islands. 1,600 people were repatriated to Turkey. The abolition of the visa requirement remained controversial. After the attempted coup in Turkey in 2016 (July), EU politicians feared that the country would fall into an injustice regime that would induce many Turks to flee to the EU without a visa.

On February 27, 2020, a high-ranking Turkish official announced in the wake of the escalating Syrian-Turkish conflict that the Turkish police, coast guards and border guards had received orders not to stop refugees' land and sea routes to Europe. This marks the de facto end of the agreement. The European border protection agency Frontex has now set the alarm level to "high" for the EU borders with Turkey and has announced that it will send emergency services and equipment there as part of a "rapid reaction force". It is being discussed whether Frontex officials should be withdrawn from other borders for this purpose. On March 19, 2020, Turkey closed the borders with the EU again.

Distribution and relocation

In Europe, it is not the European Union that grants asylum, but the Member States. Member States can, however, close their borders to refugees without being able to be put under lasting pressure to do so. For decades, all attempts to achieve a solidarity distribution of refugees have failed. According to an analysis by migration researcher Stefan Luft, European distribution agreements have the advantage of preventing tension, chaos and overloading of individual states. In times of greater population movements, however, there is hardly any incentive to agree to European distribution procedures that are automatically set in motion and to which one is then at the mercy.

The Dublin rules exclude the equal distribution of asylum seekers and asylum seekers in the EU, because they oblige the first country of entry to accept, register and clarify responsibility for the asylum procedure, and then one country to carry it out. Germany in particular benefited from this and, since 2007, has deported more asylum seekers to other EU countries than it accepted from them. The EU Commission has long been calling for a distribution key to compensate for this, and in 2010 it examined the political, financial, legal and practical possibilities of redistributing asylum seekers between European countries. However, EU-wide takeover programs could not be implemented. In particular, the economically weaker Eastern European countries, which have hardly any experience with large-scale immigration, reject the admission of refugees and a quota system. Since 2014, many returns from Germany have not been carried out, mainly because first-entry states do not guarantee asylum seekers humane treatment. The ECHR and German courts temporarily suspended transfers to Greece, Hungary, Bulgaria, Italy, Malta and Cyprus because of “systemic deficiencies” in the asylum procedures there. The ECHR obliged all Dublin states to have Italy assure them humane treatment for each individual refugee. Nevertheless, only 17% of the approximately 28,000 approved transfers to another Dublin state were carried out in 2014 because many of those affected had previously gone into hiding, host states rejected their jurisdiction and failed to carry out the mandatory EURODAC screening. The harmonization of asylum law and living conditions in Europe had been neglected or hardly attempted since the first Dublin Treaty in 1985. The EU asylum directives are implemented very differently. The strong differences in approved initial applications (protection rates) favor further migration to those states with the best chance of success for asylum applications and tolerance. The most heavily burdened host countries, in turn, tightened their border controls to the point of inhuman measures, did not allow the refugees any legal entry options and thus increased illegal locks. Since the temporary suspension of the Dublin rules in the summer of 2015, the Dublin system has practically failed. Human rights organizations are therefore calling for the criterion of first entry to be dropped and for asylum seekers to be able to freely choose the destination country, also in order to strengthen the political will to harmonize asylum law, asylum procedures, social benefits and living conditions.

In June, the Eastern European countries of the Visegrád Group and Great Britain strictly rejected a quota system. In August 2015, referendums in those states confirmed the rejection. They also rejected a new proposal by the EU Commission from September 2015, which provided for compensation payments for unfulfilled admission quotas.

On July 20, 2015, the EU Council for Justice and Home Affairs decided to regulate the resettlement of 22,504 non-Europeans worthy of protection multilaterally and nationally. This happened from October 2015, with states associated with the EU also participating. By May 12, 2017, 16,163 people, including from Turkey, had been resettled in 21 EU countries.