Transylvania

Transylvania , Transsilvanien or Transsylvanien ( Romanian Ardeal or Transilvania , Hungarian Erdély , Transylvanian Saxon Siweberjen , Greek Τρανσυλβανία , Turkish Erdel ) is a historical and geographical area in the south Carpathians with a varied history. Today Transylvania is in the center of Romania .

Designations

Transylvania is known by the following names:

- The Romanian country name is Ardeal , older Ardeliu (1432), borrowed from Hungarian, or Transilvania , taken from Middle Latin.

- The Hungarian name of the country is Erdély , older Erdeuelu ( Erdőelü ) (12th century), literally 'beyond the forest', composed of Hungarian erdő 'forest' and regional elü ( elv , el ) 'beyond, beyond, more distant side' . This "forest" refers to the densely wooded Apuseni Mountains , which separate the great Hungarian lowlands and the Kreisch area from the Transylvanian basin .

- The Middle Latin names are first terra ultra silvam (1075), ultrasylvania (1077), later Partes Transsylvana (12th century), both of which are composed of Latin ultra or trans 'beyond' and silva ' forest ' and translate the Hungarian country name.

- The designation Transylvania or Transylvania, which was Germanized on this basis, was in use in medieval documents.

The origin of the German name Siebenbürgen has not been conclusively clarified. It is presumed that it can be traced back to seven cities founded by the Transylvanian Saxons : Hermannstadt , Kronstadt , Bistritz , Schäßburg , Mühlbach , Broos and Klausenburg (in this series Mediasch is often incorrectly mentioned , but it was only raised from market to city in 1534). The seven chairs , units of their own jurisdiction - each chair had a royal judge who was solely subordinate to the Hungarian king - may also be part of the naming scheme. The name is initially recorded in German sources from the 13th century as Septum urbium , Terra septem castrorum and similar variants. In German records it was called Siebenbuergen for the first time at the end of the 13th century and at that time only referred to the area of the seven chairs as administrative units or regional authorities of the Sibiu province. Only later did the term expand spatially, finally encompassing the same space as Erdély and Ardeal , thereby replacing the earlier loan translation from Ultrasilvania Überwald (13th and 14th centuries).

location

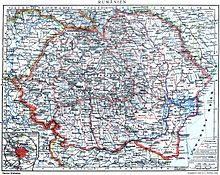

Geographically, Transylvania forms the center and north-west of Romania . Transylvania is separated from the southern ( Wallachia ) and eastern ( Moldova and Bukovina ) parts of the country by the Eastern Carpathians and the Transylvanian Alps (Southern Carpathians), which together form the southern Carpathian arch . To the west, part of the Western Romanian Carpathians , the Apuseni Mountains , separates Transylvania from the Kreisch area .

Also part of today's Romania, which until 1918/1920 to Hungary belonged (the Crisana, the region Satu Mare , the southern part of the former county of Maramures and the Romanian part of Banat ), sometimes erroneously Transilvania added, so that there is often greater than the historical area is represented.

The area of Transylvania is 59,651 km² . According to today's administrative units, all areas that belonged to Hungary until 1918 cover about 100,293 km². Transylvania is divided into the following Romanian districts :

- Alba (Karlsburg, Fehér)

- Bistrița-Năsăud (Bistritz, Beszterce-Naszód)

- Brașov (Kronstadt, Brassó)

- Cluj (Klausenburg, Kolozsvár)

- Covasna (Kovászna)

- Harghita (Szeklerburg, Hargita)

- Hunedoara (iron market, Hunyad)

- Mureș (Mieresch, Maros)

- Sibiu (Hermannstadt, Szeben)

as well as parts of the following circles:

- Bacău (the municipality of Ghimeş-Făget , the village of Poiana Sărată in the Oituz Pass , a mountain area with the Poiana Soarelui station , and the villages of Coşnea , Cădăreşti , Ciugheş and Pajiştea )

- Buzău (an uninhabited mountain area in the southeastern Carpathian arch )

- Caraș-Severin (the municipality of Băuțar )

- Maramureș (the city of Târgu Lăpuș and its surroundings)

- Neamț (the municipalities of Dămuc , Bicaz-Chei and Bicazu-Ardelean )

- Sălaj (the eastern half, east of the Meseș Mountains)

- Suceava (the villages of Cârlibaba Nouă and Dornișoara , the municipality of Coșna , as well as uninhabited mountain area southwest of the Golden Bistritz and in the source area of the Dorna , Neagra Șarului and Neagra )

- Vâlcea (a small uninhabited area north of the Lauterbach )

- Vrancea (an uninhabited mountain area in the southeastern Carpathian arch)

story

Antiquity to the time of the Great Migration

The area in which present-day Transylvania is located was the political center of the Dacian kingdom in ancient times . In the year 106 AD this was conquered by the Roman Empire under Trajan and incorporated into the Roman Empire as the province of Dacia . The capital was Ulpia Traiana Sarmizagetusa . After the withdrawal of the Roman troops under Emperor Aurelian in 272 AD, the region was a transit area and settlement area for various ethnic groups and tribal associations until the 11th century. One after another, Goths , Huns , Gepids , Avars , Bulgarians , Slavs and others appeared here . A well-known example of the archeology of the Migration Period are the Gepid tombs from Apahida .

Land conquest of the Magyars

The history during the early Middle Ages up to around 900 is characterized in Transylvania, as almost everywhere in Europe, by a lack of written sources and relatively few archaeological finds. From around 895 the Hungarians settled in the course of their conquest of the Carpathian Basin and thus also the area of today's Transylvania (see also: History of Hungary ) . Political power in the Carpathian region fell to the Hungarians with little resistance compared to other conquests of the people during the Migration Period, as the population groups encountered there formed only a few weak rulers. Presumably in the year 927 the areas south of the Mieresch were conquered by the Hungarians under the leadership of Bogát (Gyula tribal union).

Aid peoples were settled in these to secure the border areas. The most important group were the Szekler ( Székely; szék = "chair"). So-called "entanglement zones" were also created (Hungarian Gyepű ). This 10 to 40 km wide border strip was deliberately left desolate and was overgrown with thick undergrowth in order to block access to enemy armies or to make it difficult. The weak points were also secured with earth castles, the passages through gates.

The Hungarians, who still lived in tribal associations until their state was founded in 1001, did not always practice a uniform policy. After the battle on the Lechfeld near Augsburg in 955, the part of the Hungarians led by the Árpáden oriented themselves to the west, others - for example the Gyula in the area east of the Tisza (also in Transylvania) - more towards Byzantium .

Recruiting German settlers

Under King Géza II (1141–1162) the border was moved further east, from Mieresch to the Alt ; the borderland became usable. The Hungarian-speaking Szekler were resettled in today's Szeklerland, in the east of Transylvania. From around 1147 the settlement began with German settlers, who came mainly from the Middle Rhine and Moselle region, Flanders and Wallonia . The first 13 places were founded in the Sibiu area. The settlers should populate the areas, secure the borders against incursions from the east for Hungary and Europe and stimulate the economy.

In the course of the 12th and 13th centuries, settlement activity increased through internal colonization and probably also through further immigration from the Meuse - Moselle region , Flanders and the area of the archbishoprics of Cologne , Trier and Liège . In internal colonization, the Nösnerland in northern Transylvania, the area of the two chairs and the Burzenland were developed.

The term "axes" ( Saxons ) probably derives from the Latin stereotype that time Saxones for Western (mainly German) settlers. They then adopted this legal self-name themselves.

The majority of the German farmers and craftsmen enjoyed the privileges of a legal award from the Hungarian King Andreas II from 1224 ( golden license , Latin Andreanum, Hungarian Aranybulla ). This is the most extensive and best elaborated statute that has ever been granted to German settlers in Eastern Europe. The special rights were valid on the so-called royal soil , which they had settled, and were repeatedly confirmed and extended to them in documents in the following centuries. The settlers founded the most important cities in Transylvania to this day: Sibiu , Kronstadt , Klausenburg , Mühlbach , Schäßburg , Mediasch and Bistritz as well as many villages and market towns in three closed but not contiguous areas, a total of approx. 270 localities.

Further waves of immigration took place after the Counter-Reformation , as at that time there was freedom of belief in Transylvania . The so-called transmigration brought Protestants from different parts of the then Archduchy of Austria to Transylvania, who were settled there as rural residents (see below: 18th century). Between 1621/22 and 1767, larger groups of the Hutterites, who came from the radical Reformation Anabaptist movement , settled in Transylvania. The region around Unterwintz was a center of the Hutterite movement in Transylvania .

The Durlachers should be mentioned as an example of non-denominational immigration . These were people who were willing to emigrate from parts of the former margraviate of Baden-Durlach , especially from the area around Emmendingen and the Markgräflerland . Only poor subjects with many children were allowed to emigrate, but not the wealthy. The Durlacher settled in Mühlbach , among other places , of which a “Durlacher Vorstadt” and a “Durlacher Gasse” were reminiscent. Around 1770, numerous people emigrated from Hanauerland to Transylvania. The last major wave of immigration from southwest Germany to Transylvania took place between 1845 and 1848, when 1,500 to 1,800 citizens from various communities in the Kingdom of Württemberg emigrated.

Some of these immigrants remained as culturally independent groups and initially hardly mixed with the resident Transylvanian Saxons and Hungarians. The Durlachers and Hanauers in Mühlbach received their own bailiff, their own judge and their own school with a schoolmaster.

German medal

Between 1211 and 1225 the Teutonic Knight Order was also present, which the Hungarian King Andreas II had called into the country to protect against the Cumans in Burzenland . The order populated its area with German settlers. When the knights, encouraged by the Pope and Grand Master, tried to establish their own state, they were expelled and Burzenland was attached to the royal soil .

Form of government and nations

The Transylvania region developed as part of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary . The nobility with their seven counties formed an assembly of estates under the direction of a voivod ( Vajda ). The other two major regions of the country were the Königsboden (" seven chairs ": Broos , Mühlbach , Reussmarkt , Leschkirch , Hermannstadt , Schenk , Schäßburg , Reps ; later also the two chairs Mediasch and Schelk and the districts Nösnerland , Burzenland ) and the seven Szekler chairs .

The inhabitants of the Königsboden were mostly farmers, artisans, traders and some nobles who were called from the German countries, but they never played a major role and eventually became part of the people.

The Transylvanian Saxons on the royal soil enjoyed almost absolute independence, so they had their own jurisdiction ( Der Sachsen in Sybenbürgen STATUTA or Eygenlandrecht ) as well as their own political representation, called the University of Nations .

In general, there were only representations of the individual nations in medieval Transylvania , the estates . These represented the interests of the Hungarian nobles, the Transylvanian Saxons, the Szeklers and initially also the Romanians ( Universitas Valachorum ). In 1437, however, the Unio Trium Nationum was proclaimed as part of the Turkish defense , which affirmed the alliance and sole political entitlement of the estates of the Hungarian nobles, the Saxons and the Szeklers and thus excluded the Romanians.

The representatives of the three recognized nations met at state parliaments , which almost without exception took place in the German cities, and negotiated a common approach there. Most of the state parliaments took place in Medias , as it is located in the center of Transylvania and is approximately equidistant from the westernmost, easternmost and northernmost corners of the royal floor .

The Romanians, on the other hand, were excluded from political and social life: after 1437 they were no longer represented or had a say. Under constitutional law, they were only tolerated until the 19th century and were deliberately excluded. B. They were not allowed to settle in the German cities or buy houses there (although that was actually forbidden to all other nationalities except the Saxons), nor to join the local guilds . For example, in an old guild order from Schäßburg it says: "eyn Gesell should be honorable, pious and of German kind". Anyone who was not German was denied any access to trade and change in the up-and-coming Saxony cities in the medieval Sybenbuergen , which at that time were the only urban centers.

16th to 17th centuries

When the Hungarian army was defeated by Suleyman I in the Battle of Mohács on August 29, 1526 , a phase of constant threat to the country began for almost 200 years. Central Hungary in particular was devastated by the Turkish advance into Hungary (1526–1686). More than a hundred thousand prisoners were deported to the Ottoman Empire .

Hungary eventually broke into three parts. Most of Hungary came under Turkish rule, with the areas not yet conquered either coming under Habsburg rule (including the west of Upper Hungary or Royal Hungary ) or separated from Hungary and as a subordinate principality of Transylvania (Hungarian: Erdélyi Fejedelemség ) under the suzerainty of the Ottoman in 1541 Empire were put.

Suleyman I concluded a peace treaty with Johann Zápolya as early as 1528 , in which he relied on the weakening of the Habsburg Empire by the later principality of Transylvania . Transylvania remained a vassal state of the Sublime Porte until the end of the 17th century . Domestically, this meant freedom, but foreign-policy it meant Turkish control, approval of the prince elected by the estates (Hungarian rend , plural rendek ) by the High Porte, as well as annual tribute payments. However, it was exactly as before to Ottoman assaults and plundering in the area of Seven Chairs and beyond, where the Turks themselves as so-called. Renner and burner operated and devastation, murder and kidnapping ensured. Despite the Turkish sovereignty, Transylvania remained a Christian country in which not a single mosque was ever built. By 1568 the Transylvanian parliament adopted Edict of Torda religious freedom was first anchored and Catholics, Reformed, Lutherans and Unitarians alike legally recognized.

For Transylvania as a social and economic entity, the 17th century was a time of great upheaval and constant threats from outside and inside. The Hungarian magnates in Transylvania adopted the strategy of leaning against one or the other great power, depending on the situation, and trying to maintain their own independence. The Báthory family z. B., who came to power after the death of Johann Sigismund Zápolyas in 1571, placed the princes of Transylvania under Ottoman and brief Habsburg rule until 1602. Due to the precarious political constellation, the political and military interests of the Transylvanian princes differed from those of the royal Hungary fundamental at this time. The princes Gábor Bethlen and Georg I. Rákóczi sometimes even led regular campaigns against the Habsburg kings on the Hungarian throne.

The princes - above all Gabriel Báthory - and the Turkish invasions tormented the people without ceasing. Campaigns, looting and civil unrest devastated the country. Epidemics, famine and the Turkish raids, in which thousands of prisoners were taken each time, decimated the population. Horrific taxes, tributes to the Turks, billeting and supplying the armies that were passing through harassed the residents. In addition, the nations (see Nations University ) were divided, the government apparatus sank into corruption and so the principality became the plaything of the powerful.

In 1610, Prince Báthory convened the state parliament in Sibiu. He moved up with an army in front of the fortified city and, by means of a ruse, came into possession of the keys to the city gates. Thereupon he accused the citizens of treason, extorted a large ransom, had the capital plundered, the citizens' weapons collected on the Great Ring and chased the residents out of the city. From Sibiu he began a raid and desolation through the Königsboden , which finally ended only with his murder.

After the victory over the Ottomans in the second Turkish siege of Vienna in 1683 , Transylvania tried in vain to defend itself against the growing influence of Austria. The Habsburg rule was established in stages: in 1686 and 1687, Prince Michael I. Apafi , who was appointed by the Ottoman Empire in 1661, was forced to come to terms with the Habsburgs due to the advance of the Austrian troops and, in contracts with Emperor Leopold I, the suzerainty of the Emperor to recognize his status as King of Hungary ; In 1688 the agreement was confirmed by the Transylvanian state parliament. Apafi died in 1690. On December 4, 1691, the Leopoldine Diploma was issued, the country's basic contract with the House of Austria. In 1697, the 21-year-old son of Apafis, Michael II. Apafi , who had reigned as prince under Leopold I's guardianship since 1692, renounced the principality in return for compensation. In 1699, Transylvania was recognized as part of Austria by the Ottoman Empire in the Treaty of Karlowitz .

18th century

With the Peace of Sathmar in 1711, Austrian control over all of Hungary and Transylvania was finally established. Transylvania, which remained independent from the Kingdom of Hungary, was now administered by so-called gubernators under the supervision of the Viennese court . The proclamation of the Grand Duchy of Transylvania in 1765 and the conversion into an Austrian crown land were formal acts. Maria Theresa and her son Joseph II, who had been co-ruling since 1765 , endeavored to administer their territory uniformly, and to this end they set up a government in Vienna that overruled the special regulations of individual crown lands that had previously been enforced. Through a certificate from Maria Theresa dated November 2, 1775, Transylvania was largely autonomous and ruled by its own princes according to its own laws.

From 1733 the ethnic group of the so-called Transylvanian Landler was settled in southern Transylvania. She was under Charles VI. and Maria Theresa forcibly deported to Transylvania. Since the Protestant faith was forbidden in the Austrian hereditary lands, but individual convinced Protestant groups ( crypto- Protestants ) from the princely Salzkammergut , the Land ob der Enns (the "Landl"), Styria and Carinthia , they were banished to the easternmost corner of the Habsburg Empire. In a letter from the Transylvanian Court Chancellery, it says: "Your Imperial Majesty [meaning Maria Theresia] decided to isolate these people in the Principality of Transylvania, because the same thing that is most remote from the population suffers from a lack of correspondence ..." In Transylvania, which at that time was still on the military border with the Ottoman Empire , had always been Protestants with the Transylvanian Saxons and there was general tolerance . In addition, there were many orphaned farms on Königsboden in the Transylvanian-Saxon villages. Under the euphemistic name of " transmigration ", the Landler were brought across the Danube to Transylvania in several batches between 1734 and 1776 in Ulmer Schachteln .

In the under forest devastated and depopulated by the Turkish wars, as well as in the Sibiu area, the so-called “ exiles ” were allowed to settle in several villages in the middle of the Transylvanian Saxons who had been living here for centuries. Only in the three villages of Neppendorf , Großau and Großpold were they able to maintain themselves as a separate group in the long term.

The Romanians now made up the majority of the population of Transylvania. They did not have political rights. In particular, those of them who lived as serfs under the rule of Hungarian nobles on county soil were also in very difficult economic circumstances. The tensions erupted in 1784 in a great peasant revolt under Horea . In 1791 the Romanians asked Leopold II at the state parliament in Cluj in the Supplex Libellius Valachorum for the fourth time to be accepted as the fourth “natio” of Transylvania (alongside the Hungarian nobility, the Szeklers and the Transylvanian Saxons ) and for further political recognition. However, these demands were refused to them by the three other nations in the state parliament.

19th century

As part of the revolutions of 1848 against the Habsburg rule, the Hungarian insurgents proclaimed, among other things, the reunification of Transylvania with Hungary, the independence of the Kingdom of Hungary from Vienna, the abolition of serfdom and much more (see Hungarian Revolution 1848/1849 and Romanian Revolution of 1848 ). However, Austria was able to suppress the Hungarian striving for independence with Russian support in 1849. For the next five years (1849-1854) Transylvania was under Austrian military administration. As one of the few outcomes of the revolution, the abolition of serfdom remained in force throughout the empire as well as in Transylvania.

In 1866 the Magyar-dominated state parliament decided (to the detriment of the other nationalities) in favor of the union with Hungary, which was carried out with a royal rescript of January 1867 (in view of the compromise negotiations between the Viennese court and Hungary) ; with this the autonomous status of Transylvania, which had existed for more than 700 years, was abolished. With this act, the self-government of the Transylvanian Saxons , the national university and the old rights associated with it were abolished, the royal soil was abolished. The same applied to the special rights of the Szeklers.

In February and March 1867 there was an equalization and thus the establishment of the dual monarchy Austria-Hungary. Transylvania was confirmed as part of the Hungarian half of the empire .

In Hungary, which was now internally independent, the Hungarian people were a minority (albeit a large one), so that the royal government in Budapest feared that the state's integrity would be broken. Therefore, after the compromise, a rigid policy of Magyarization was started, which stipulated the exclusive use of the Hungarian language in all public life and led to constant conflicts with non-Hungarian sections of the population. The Transylvanian Saxons were, however, able to evade these constraints as much as possible through their denominational schools and a large number of associations and foundations - especially the Nations University Foundation . Other ethnic groups such as the Sathmar Swabians were far less successful in this regard. Because of their large number and their proximity to the Kingdom of Romania, the Romanians resisted Magyarization and saw themselves systematically and on many levels disadvantaged by the ruling Hungarians. The recognition of languages other than Hungarian as educational and official languages was of particular importance to many here.

20th and 21st centuries

In 1907 natural gas was discovered in Sărmășel (today a cadastral municipality of the small town of Sărmașu ) while mining for salt and in 1909 the first drilling rigs for natural gas production were erected. In the following years, further gas fields were drilled around Mediasch and in 1914 the first natural gas pipeline in Europe was put into operation. For the purpose of efficient prospecting and extraction of methane gas in Transylvania, an agreement was signed in 1915 between the Hungarian Ministry of Finance and Deutsche Bank , on the basis of which the Hungarian Methane Gas Company was founded. The natural gas deposits led to the rapid industrial development of Mediasch and Kleinkopisch , in the vicinity of which most of the natural gas probes were located. The methane gas was used as a raw material in glass production and the chemical industry; it was also used for lighting and as fuel for engines.

After the defeat of Austria-Hungary in the First World War , around 100,000 Romanians gathered in Alba Iulia (Karlsburg) on December 1, 1918 and proclaimed the unification of all Romanians from Transylvania, the Banat , the Kreischgebiet and Maramures with the Romanian Altreich . Some of these regions were inhabited by Hungarians to more than 90 percent (e.g. Szeklerland, Partium mit Großwardein, the Sathmar region), others predominantly by Transylvanian Saxons (here e.g. Sibiu area, wine country around Mediasch, Burzenland, Nösnerland).

In the Medias declaration of affiliation in February 1919, the Transylvanian Saxons welcomed the resolutions passed in Alba Iulia, in which the Transylvanian Saxons were guaranteed extensive minority rights, and the annexation to Romania. At the Saxon Day in Schäßburg , expectations of the new Romanian unified state were formulated, which, however, largely disappointed them.

The takeover of Transylvania by Romania was enshrined in the Treaty of Trianon in 1920 . The Romanian administration now operated everywhere in the country according to the logic of a centrally managed nation-state, just like the Hungarian state before. The particularism- based self-image of the many Transylvanian ethnic groups (Romanians, Szeklers, Transylvanian Saxons, Armenians, Jews) was severely impaired. In theory, minorities were granted more extensive rights than during Hungarian rule; however, these were not always used in practice.

The ethnic groups that had dominated politically, economically and culturally for centuries now lost their historical supremacy in favor of the Romanian majority population. The measures (including expropriations, confiscations, dismissals, discrimination and the dissolution of or forcing out of institutions) by the Romanian state and attacks against the Hungarian population group aimed at total control over Transylvania. Those affected perceived this policy as an affront, an injustice and an attempt at marginalization or assimilation.

The situation prompted not a few Magyars to emigrate to the new, smaller Hungarian state. At the same time, a targeted settlement of ethnic Romanians from the Old Reich (Regat) in Transylvania took place in the interwar period . This policy was continued on a massive scale after the Second World War and led in almost all districts of Transylvania to the reversal of the old majority in regions previously populated by a majority of Hungarian or German people in favor of ethnic Romanians. Exceptions to this day are the Szekler districts of Harghita and Covasna , in which the ethnic Hungarians still make up over three quarters of the population.

During the Second World War in 1940 in the so-called Second Vienna Arbitration under the direction of the German Reich, a crescent-shaped section along the north and north-east border of Transylvania, in which about the same number of Hungarians and Romanians lived, was transferred to Hungary. Southern Transylvania, predominantly inhabited by Romanians and Transylvanian Saxons, remained with Romania. On the occasion of the division, population movements also took place. At the end of 1944 the ceded territory came under Romanian control again after Romania changed sides to the Soviet Union . Most of the Transylvanian Saxons from northern Transylvania fled to Austria or Germany after the collapse of the German front. From the end of the war in 1945, there were attacks against the German and Hungarian populations throughout Transylvania, which lasted for several years.

The boundaries laid down in the Treaty of Paris in 1947 were identical to those of 1920 with regard to Transylvania and north-west Romania. The vast majority of Transylvanian Saxons emigrated since the 1970s, and in a major surge from 1990, mainly to the Federal Republic of Germany , but also to Germany Austria . The Transylvanian Saxon Klaus Johannis has been President of Romania since 2014 .

coat of arms

- The shield, divided by a narrow red crossbar , above in blue a growing black eagle with a golden beak and red tongue, accompanied by a golden sun and silver moon , below in gold seven towers (4: 3) placed. On the coat of arms the grand prince's hat .

The components of this coat of arms also form the seal and coat of arms of the three estate nations of Transylvania, namely the Magyars, the Szeklers and the Transylvanian Saxons.

The coat of arms of Transylvania consists of a shield, which is divided into two equal fields by a red, horizontal bar. In the upper field there is a black eagle on a blue background. He represents the Magyars (Hungarian nation). To the left and right of the eagle there is a white moon and a yellow sun, which symbolize the Szekler (Szekler Nation). In the lower field of the shield there are seven red castles on a yellow background, which represent the Transylvanian Saxons (Saxon nation).

What is striking about this coat of arms is that it does not contain a symbol for all ethnic groups in Transylvania. As an example, the Romanians of Transylvania, despite their non-negligible number, were not a class nation in the legal sense and therefore did not have the right to own a seal. The Romanians and the various ethnic minorities of Transylvania (including Armenians, Jews, Roma) had no political rights at the time.

As part of the coat of arms of Austria-Hungary from 1857 to 1919

As part of the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Hungary from 1867 to 1918

As part of the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Romania from 1922 to 1948

As part of the coat of arms of Romania from 1989 until now

population

Ethnic groups

Around 1930, Transylvania, in the narrower sense, had around 2.7 million inhabitants. Of these, 56.4 percent were Romanians , 23 percent Hungarians and 9.4 percent German . Other minorities are Roma , Ukrainians , Serbs , Croats , Slovaks , Armenians and Jews . The last two groups, however, have almost completely disappeared these days.

| year | Total | Romanians | Hungary | German | Roma | Ukrainians | Serbs | Slovaks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1869 | 4,224,436 | 59.0% | 24.9% | 11.9% | 1.3% | 0.4% | 1.1% | 0.5% |

| 1880 | 4,032,851 | 57.0% | 25.9% | 12.5% | 1.5% | 0.3% | 1.3% | 0.6% |

| 1890 | 4,429,564 | 56.0% | 27.1% | 12.5% | 1.4% | 0.3% | 1.1% | 0.6% |

| 1900 | 4,840,722 | 55.2% | 29.4% | 11.9% | 0.6% | 0.4% | 1.0% | 0.6% |

| 1910 | 5,262,495 | 53.8% | 31.6% | 10.7% | 1.2% | 0.4% | 1.0% | 0.6% |

| 1919 | 5,259,918 | 57.1% | 26.5% | 9.8% | - | - | - | - |

| 1920 | 5,208,345 | 57.3% | 25.5% | 10.6% | - | - | - | - |

| 1930 | 5,114,214 | 58.3% | 26.7% | 9.7% | 0.8% | 0.4% | 0.8% | 0.7% |

| 1941 | 5,548,363 | 55.9% | 29.5% | 9.0% | - | - | - | - |

| 1948 | 5,761,127 | 65.1% | 25.7% | 5.8% | - | - | - | - |

| 1956 | 6.232.312 | 65.5% | 25.9% | 6.0% | 0.6% | 0.5% | 0.7% | 0.3% |

| 1966 | 6,736,046 | 68.0% | 24.2% | 5.6% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.6% | 0.3% |

| 1977 | 7,500,229 | 69.4% | 22.6% | 4.6% | 1.6% | 0.6% | 0.4% | 0.3% |

| 1992 | 7,723,313 | 75.3% | 21.0% | 1.2% | 1.1% | 0.6% | 0.4% | 0.2% |

| 2011 | 6,789,250 | 70.6% | 17.9% | 0.4% | 3.9% | 0.6% | - | - |

In the 2002 census, Transylvania had a population of 7,221,733, of which 74.69 percent Romanians, 19.60 percent Hungarians, 3.39 percent Roma and 0.73 percent German (approx. 60,000).

Of the approximately 60,000 Germans in Romania, the Transylvanian Saxons now make up only around 14,000. Their emigration has now subsided, but the remaining German population is so aging that their number continues to shrink due to high death rates.

religion

These beliefs are mainly represented in Transylvania:

- Romanian Orthodox Church

- Romanian Greek Catholic Church

- Roman Catholic Church in Romania ( List of Bishops of Transylvania )

- Protestant churches:

- Calvinists / Reformed (Hungary), Reformed Church in Romania

- Lutherans (Hungarians, Germans and Slovaks), Evangelical Lutheran Church in Romania (mainly Hungarian-speaking) and Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession (German-speaking). The German-speaking Lutherans are referred to by the term Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession , which is also common in Austria .

- Unitarian (Hungarians / Szekler), Unitarian Church of Transylvania

Most of the members of the Protestant and Catholic churches are of German and Hungarian descent. There are also some small Jewish communities. Various free churches are also strongly represented, such as the Pentecostal movement , the Baptists , the Adventists and the Jehovah's Witnesses , which the other groups generally refer to as "converts" (Romanian: pocăiți ) and with support from Germany and the USA since the end of the Communism record strong growth. The radical Reformation Hutterites as well as the Sabbatars , who emerged from Unitarianism, are no longer represented in Transylvania today.

The most important pilgrimage sites in Transylvania are Șumuleu Ciuc (Hungarian Csíksomlyó , Franciscan monastery ), Nicula ( Basilian monastery , used by the Romanian Orthodox Church since 1948) and the Sâmbăta de Sus (Romanian Orthodox) monastery .

Organs

More than 1500 organs have been preserved in the churches of Transylvania , from small positive organs to representative instruments with several thousand pipes. Especially in the Evangelical Lutheran churches of the Saxons, but also in the worship service of the Reformed Church, the instrumentally accompanied parish singing played an important role. For centuries there was a living organ-building tradition in Transylvania. A number of regional organ workshops existed in the 19th and early 20th centuries. After 1945, organ building in communist-ruled Romania almost came to a complete standstill. The organ builder Hermann Binder has rendered outstanding services to the preservation and restoration of the Transylvanian organs . In 2007, on the initiative of the Swiss organ builder Barbara Dutli, an organ workshop was founded in Honigberg , which gradually restores organs that have been preserved and trains organ builders.

In some city churches such as the Black Church in Brașov or the Margaret Church in Mediaș , the restored and well-preserved organs can be heard regularly. In contrast, the organs in smaller village churches are often no longer playable: Due to the emigration of the Transylvanian-Saxon communities after 1990, many smaller village churches are orphaned. The temperature differences in the unheated buildings, rodent infestation and lack of maintenance endanger the preservation of the organs. Some of them were therefore moved to central locations - such as the churches in larger cities. Some of them have been restored and can be played there again, others are only kept in museums. Famous are the organs of the Black Church in Kronstadt , as well as the baroque organ of the Margaret Church of Mediasch , built in 1755 by Johannes Hahn. The great organ builders include Johannes Prause (1755–1800) and Samuel Joseph Maetz (1760–1826). Wilhelm Georg Berger wrote important organ works.

kitchen

A staple food in Transylvanian cuisine is maize , which is eaten mainly in rural areas as a porridge made from maize flour (palukes, polenta , mămăligă ) on many occasions and at all times of the day, sometimes with milk, as a casserole with sheep's cheese or as a side dish to meat , Cabbage or goulash.

Another important food is the potato , which is mainly prepared as jacket potatoes, boiled as sterz , fried as fried potatoes or mashed potatoes . Also typical of the Transylvanian cuisine is a dark, heavy brown bread that has to be kneaded for a long time, is extremely filling and is sometimes enriched with potatoes. It is baked in large, heavy loaves (from two kilograms, traditionally usually even larger) and often eaten as lard bread with salt, pepper and (spring) onions.

Originally, the kitchens of the three ancient ethnic groups differ considerably, but have in some parts become the same over time. Typical of the Romanian-Transylvanian cuisine are, for example, sour soups ( Ciorbă ), for the Hungarians hot spices with paprika and caraway seeds and for the Transylvanian Saxons meat soups with fruit (plum soup, grapevine soup, rhubarb soup etc.) and pastries.

Flora, fauna and landscape

Transylvania has a very high biological diversity . In particular, the cultural landscapes on which traditional small-scale agriculture is practiced are among the most biodiverse areas in Europe. The extensively used pastures and hay mowings are particularly rich in insects and amphibians, as well as typical meadow birds. Pastures and deciduous forests dominate the landscape. As in large parts of Transylvania, the wave of emigration by the German-speaking minority and the social upheaval after reunification led to land being set aside . This could also cause this traditional cultural landscape and its unique biodiversity to be lost if land use is intensified.

The diversity of the landscape in Transylvania is unique in Europe: there is an interplay of extensively farmed areas, "intact" villages and traditional agriculture, as existed in other parts of Europe in the 19th century. In addition to the rich flower meadows, wolves and bears are also found in the relatively low regions of Transylvania.

Conservation and sustainable development

The construction of roads and an intensification of agriculture are also promoted in Transylvania with EU agricultural subsidies and pose a threat to numerous species, especially amphibians . According to scientific studies, roads have the greatest impact on their populations. Other factors such as the size of the ponds, settlements, arable land, pasture land, forest or wetlands had a significantly lower impact.

The preservation of the traditional, extensive land management is seen by some scientists as the key factor for the protection of the high biodiversity. However, accession to the EU is likely to lead to more intensive land use and a growth in infrastructures in many regions. This in turn results in a fragmentation of the landscape and a general loss of quality from an ecological point of view, of the remaining habitats.

Personalities

writer

- Endre Ady (1877-1919), Hungarian poet

- János Arany (1817–1882), Hungarian poet

- Miklós Bánffy (1873–1950), Hungarian writer and politician

- Hans Bergel (* 1925), writer and journalist

- Lucian Blaga (1895–1961), philosopher , journalist, poet, translator, scientist and diplomat

- Ion Budai-Deleanu (1760-1820), writer, historian, linguist

- Emil Cioran (1911–1995), philosopher

- George Coșbuc (1866-1918), writer, poet

- Dan Dănilă (* 1954), poet and translator.

- Deak Tamas (1928–1986), Hungarian writer

- Jenő Dsida (1907–1938) Hungarian poet; Poems: Leselkedő Magány (1928), Jövendő havak himnusza (1923–1927) etc.

- Zsigmond Kemény (1814–1875) Hungarian writer, politician and journalist.

- Ferenc Kölcsey (1790–1838), Hungarian poet, language reformer, politician and creator of the Hungarian national anthem

- Georg Maurer (1907–1971), poet, essayist and translator

- József Nyírő (1889–1953), Hungarian writer, journalist and priest

- Octavian Goga (1881–1938), poet, dramaturge, politician

- Octavian Paler (1926–2007), writer, poet and publicist

- Oskar Pastior (1927-2006), poet

- Liviu Rebreanu (1885-1944), writer

- Sándor Reményik (1890–1941), Hungarian poet

- Eginald Schlattner (* 1933), novels: Red Gloves , The Beheaded Rooster , The Piano in the Fog

- Dieter Schlesak (1934–2019), writer, member of the PEN Center Germany

- Paul Schuster (1930-2004)

- Hellmut Seiler (* 1953), poet, translator and satirist

- Ioan Slavici (1848–1925), writer and journalist

- Gertrud Stephani-Klein (1914–1995), writer, publicist

- Áron Tamási (born: János Tamás) (1897–1966), Hungarian novels and short stories

- Albert Wass (Count of Szentegyed and Czege) (1908–1998), writer, poet

- Joachim Wittstock (* 1939), writer and essayist

- Iris Wolff (* 1977), writer

Visual artist

- Fritz Schullerus (1866–1898), painter, draftsman

- Eduard Morres (1884–1980), painter, draftsman, art teacher

- Hans Mattis-Teutsch (1884–1960), painter, graphic artist, sculptor, art theorist, art teacher

- Hermann Morres (1885–1971), painter, graphic artist, musician, art teacher

- Hans Hermann (1885–1980), painter, graphic artist, draftsman and art teacher

- Margarete Depner (1885–1970), sculptor, painter, draftsman

- Trude Schullerus (1889–1981), painter

- Henri Nouveau (Henrik Newborn) (1901–1959), painter, sculptor, composer, pianist, writer, art theorist

- Karl Hübner (1902–1981), painter and graphic artist

- Harald Meschendörfer (1909–1984), painter, graphic artist, art teacher

- Helfried Weiß (1911–2007), painter, draftsman and art teacher

- Friedrich von Bömches (1916–2010), painter, graphic artist and photographer

- Adelheid Goosch (* 1929), painter, graphic artist, sculptor, art teacher

- Juliana Fabritius-Dancu (1930–1986), painter, folklorist and art historian

Other personalities

Sorted by year of birth

- Johannes Honterus (1498–1549), humanistic scholar, reformer, printer (from 1539 operator of the first permanently important printing company in Transylvania), operator of a paper mill, school man and picture carver

- Johannes Caioni (1629–1687), Franciscan, composer, organ builder and printer

- Samuel von Brukenthal (1721–1803), politician, governor of Transylvania, art collector, founded the Brukenthal Museum in Sibiu

- Georgius Stephani (1740–1762), Transylvanian freedom fighter

- Lukas Joseph Marienburg (1770–1821), historian, teacher and pastor

- Johann Martin Honigberger (1795–1869), doctor, pharmacist and oriental researcher

- Stephan Ludwig Roth (1796–1849), pastor, teacher, school reformer, writer and politician

- Franz Conrad (1797–1846), politician, diplomat, court agent of the royal Transylvanian court chancellery in Vienna and authorized representative of the Saxon nation

- Josef Haltrich (1822–1886), teacher, collector of fairy tales, folklorist

- Franz Obert (1828–1908), parish priest of Kronstadt , writer, school reformer and politician.

- Carl Eduard Conrad (1830–1906), politician, member of the Royal Hungarian Diet in Budapest, public notary public in Kronstadt

- Eduard Gusbeth (1839–1921), doctor and medical historian in Kronstadt

- Christian Friedrich Maurer (1847–1902), historian, playwright and high school teacher

- Franz Karl Herfurth (1853–1922), Protestant theologian

- Arthur Arz von Straussenburg (1857–1935), 1917/1918 last Chief of Staff of the Austro-Hungarian Army

- Heinrich Siegmund (1867–1937), doctor, state consistory advisor and publicist

- Oswald Thomas (1882–1963), astronomer and university professor

- Hermann Oberth (1894–1989), physicist and space pioneer

- Alfred Csallner (1895–1992), pastor, from 1936 head of the State Office for Statistics

- Brassaï (civil Gyula Halász ) (1899–1984), photographer

- Samu von Borbely (1907-1984), mathematics professor

- Ernő Grünbaum (1908–1944 / 45), cubist and expressionist painter

- Arnold Graffi (1910–2006), doctor at the Charité in Berlin and scientific pioneer in the field of cancer research

- Richard Kepp (1912–1984), gynecologist and obstetrician, professor and from 1965 to 1966 rector of the Justus Liebig University in Giessen

- Ernst Wagner (1921–1996), author of fundamental regional studies on the history of Transylvania and the Transylvanian Saxons

- Helmut Plattner (1927–2012), organ virtuoso

- Peter Maffay (* 1949 as Peter Alexander Makkay ), singer and musician

- Josef Kappl (* 1950), musician, bassist and composer

- Ralph Gunesch (* 1983), ehm. Football professional, football commentator and football coach

places

Some major cities in Transylvania:

- Cluj-Napoca (German Klausenburg , Hungarian Kolozsvár )

- Brașov (German Kronstadt , Hungarian Brassó )

- Sibiu (Romanian Sibiu , Hungarian Nagyszeben )

- Târgu Mureș (German Neumarkt am Mieresch , Hungarian Marosvásárhely )

- Bistrița (German Bistritz , Hungarian Beszterce )

- Alba Iulia (German Karlsburg , formerly Weißenburg , Hungarian Gyulafehérvár )

- Deva (German Diemrich , Hungarian Déva )

- Hunedoara (German iron market , Hungarian Vajdahunyad )

- Turda (German Thorenburg , Hungarian Torda )

- Mediaș (German Mediasch, Hungarian Medgyes )

- Sighișoara (German Schäßburg , Hungarian Segesvár )

- Miercurea Ciuc (German Szeklerburg, Hungarian Csíkszereda )

- Sebeș (German Mühlbach , Hungarian Szászsebes )

For more places see category: Place in Transylvania

See also

- Transylvanian Saxony

- Magyars in Romania

- List of historical regions in Romania and the Republic of Moldova

- Dacia

- List of the Princes of Transylvania

- History of romania

- History of Hungary

- List of the historical counties of Hungary

- List of German and Hungarian names of Romanian places

- Screeching area

- Banat

- Máramaros county

- Burzenland

literature

Complete presentations on the history of Transylvania and the Transylvanian Saxons

in order of appearance

-

Georg Daniel Teutsch , Friedrich Teutsch (ed.): History of the Transylvanian Saxons for the Saxon people . Verlag Wilhelm Krafft , Hermannstadt

- Vol. 1: From the oldest times to 1699 . 1899.

- Vol. 2: 1700–1815: From the Kuruzzenkriegen to the time of the regulations . 1907.

- Vol. 3: 1816–1868: From the time of regulations to the introduction of dualism . 1910.

- Vol. 4: 1868-1919: Under the dualism . 1926.

- Constantin C. Giurescu: Transylvania in the history of Romania. An historical outline . Garnstone Press, London 1969. ISBN 0-900391-40-5 .

- Ludwig Binder, Carl Göllner , Elisabeth Göllner, Konrad Gündisch: History of the Germans on the territory of Romania , Vol. 1: 12th century to 1848 . Published by the Research Center of the Sibiu University Institute. Kriterion Verlag, Bucharest 1979.

- Ernst Wagner: History of the Transylvanian Saxons. An overview . Wort und Welt Verlag, Thaur near Innsbruck 1981 (and numerous other editions). ISBN 3-85373-055-8 .

- Milton G. Teacher: Transylvania. History and Reality . Bartleby Press, Silver Spring 1986. ISBN 0-910155-04-6 .

- András Mócsi, Béla Köpeczi (ed.): Erdély története , 3 volumes. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1986. ISBN 963-05-4203-X (translation of the Hungarian title: History of Transylvania).

- Béla Köpeczi, Gábor Barta (ed.): A short history of Transylvania . Published by the Institute of History of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1990. ISBN 963-05-5667-7 .

- Harald Roth : A Brief History of Transylvania . Böhlau, Köln / Weimar / Wien 1996 (1st edition), 2003 (2nd edition), 2007 (3rd edition), ISBN 978-3-412-13502-7 (3rd edition).

- Konrad Gündisch: Transylvania and the Transylvanian Saxons . Langen Müller, Munich 1998 (1st edition), 2005 (2nd edition), ISBN 3-7844-2685-9 (2nd edition).

-

Michael Kroner : History of the Transylvanian Saxons . Verlag Haus der Heimat, Nuremberg

- Vol. 1: From the settlement to the beginning of the 21st century . 2007, ISBN 978-3-00-021583-4 .

- Vol. 2: Economic and cultural services . 2008, ISBN 978-3-00-024223-6 .

- Michaela Nowotnick: Autumn over Transylvania - Only a few Romanian Germans stayed in their homeland after 1989 - it is important to secure their legacy . In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung, international edition, December 31, 2016, p. 20

- Andres Wysling, Gheorgheni: The German course on the roller - a development model emerges out of necessity . Young farmers from Transylvania travel to Switzerland for internships or seasonal work ... In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung, international edition, international section, October 5, 2016, p. 7

- Elmar Schenkel: Transylvania runs in his blood - salvation for an old world : Prince Charles' commitment in Transylvania. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, category literary life, November 12, 2016, No. 265, p. 18

- Christoph Strauch: The neglected people of Transylvania - in 1920 Hungary had to cede Transylvania to Romania - the Hungarian minority still does not feel at home there to this day. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Frankfurt am Main, Tuesday, July 25, 2017, No. 170, p. 3 under the heading "Politics".

Individual aspects of the Transylvanian history and culture

in alphabetical order of the authors

- Meinolf Arens: Transylvania - Transylvania, Marmarosch and Kreischgebiet. In: Thede Kahl, Michael Metzeltin, Mihai-Răzvan Ungureanu (eds.): Romania. Space and population - history and images of history - culture - society and politics today - economy - law - historical regions . LIT, Vienna 2006. ISBN 3-8258-0069-5 . Pp. 881-902.

- Elemér Bakó, William Sólyom-Fekete: Hungarians in Rumania and Transylvania. A bibliographical list of publications in Hungarian and West European languages . Compiled from the holdings of the Library of Congress, Washington DC 1969.

- Wilhelm Andreas Baumgärtner: In the sign of the crescent moon. Transylvania in the time of the Turkish wars. Schiller, Hermannstadt / Bonn 2009.

- Kai Brodersen : Dacia Felix. Ancient Romania in the focus of cultures. wbg Philipp von Zabern, Darmstadt 2020. ISBN 978-3-8053-5059-4 .

- Márta Fata: Migration in the cameralistic state of Joseph II. Theory and practice of settlement policy in Hungary, Transylvania, Galicia and Bukovina from 1768 to 1790 . Aschendorff, Münster 2014, ISBN 978-3-402-13062-9 .

- Cristina Fenean: Constituirea principatului autonomous al Transilvaniei . Bucurenti, 1997.

- Arne Franke: The defensive Sachsenland. Fortified churches in southern Transylvania , German Cultural Forum for Eastern Europe, Potsdam 2007 ( online ).

- Helmut Gebhardt: On the school history of Transylvania from the 15th to the 18th century . Einst und Jetzt , Vol. 23 (1978), pp. 322-326.

- Ion Grumeza: Dacia. Land of Transylvania, cornerstone of ancient Eastern Europe . Hamilton Books, Lanham 2009. ISBN 978-0-7618-4465-5 (on the history of Dacia in Roman times).

- Josef Haltrich : Saxon folk tales from Transylvania . Bucharest 1973. (importance for folklore and language)

- Arnold Huttmann : Medicine in old Transylvania. Contributions to the history of medicine in Transylvania. Edited by Robert Offner, Hermannstadt (Sibiu) 2000.

- Walter König: Contributions to the Transylvanian school history (= Transylvanian archive. 32). Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 1996.

- Walter König: Schola seminarium rei publicae. Essays on the past and present of the school system in Transylvania and Romania (= Transylvanian Archive. 38). Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 1996.

- János Michaelis: Austrian patriotism with special regard to the Crown Land of Transylvania . Filtsch, Hermannstadt 1858 ( digitized version ).

- Sorin Mitu (ed.): Interethnic and civilization relationships in Transylvania. Historical studies . Association of Historians from Transylvania and the Banat, Babes Bolyai University, Cluj 1996. ISBN 973-9261-11-6 .

- Robert Offner: The medical knowledge exchange between Transylvania and other European countries as reflected in the study abroad and the medical training of Transylvanians before the establishment of the University of Cluj (1872). In: Reports on the history of science. Volume 24, Issue 3, Weinheim 2001.

- Anselm Roth: Transylvanian guest houses. Schiller, Hermannstadt / Bonn 2007.

- Anselm Roth, Holger Wermke: World cultural heritage in Transylvania. Schiller, Hermannstadt / Bonn 2009.

- Gertrud Stephani-Klein: Sunken German villages in Transylvania (III). In: Südostdeutsche Vierteljahresblätter (Munich), Issue 26/1, 1977, pp. 1-7.

- Gertrud Stephani-KLein: Ten German settler groups still live in Romania today. In: Kulturpolitische Korrespondenz (Bonn), No. 424, November 5, 1980, pp. 3–6.

- Gertrud Stephani-KLein: Ten groups of settlers can still be identified today. Romania's German population. In: Structure. Deutsch-Judenische Zeitung (New York), 5/8, January 2, 1981, p. 15 ff.

- Fabian Törner, Andreas Heldmann : Dissertatio historica de origine septem castrensium Transilvaniae Germanorum . Werner, Uppsala 1726 ( digitized version ).

- Joseph Trausch : Writer's lexicon or biographical-literary thought sheets of the Transylvanian Germans. 3 volumes. Kronstadt 1868–1871; Unchanged reprint: Cologne / Vienna 1983.

- Michael Welder : Transylvania. A journey of discovery in pictures . Verlag Gerhard Rautenberg, Leer 1992, ISBN 978-3-7921-0485-9 .

- Ulrich A. Vienna, Krista Zach (ed.): Humanism in Hungary and Transylvania. Politics, Religion and Art in the 16th Century (= Transylvanian Archive. Volume 37). Cologne / Weimar 2004.

University theses

- Florian Kührer-Wielach: Transylvania without Transylvanians? State integration and new offers of identification between regionalism and national unitary dogma in the discourse of the Transylvanian Romanians. 1918–1933 (= Southeast European Works , Volume 153), de Gruyter, Berlin / Munich / Oldenburg / Vienna 2014, ISBN 978-3-11-037890-0 (Dissertation on Doctor of Philosophy (Dr. Phil.) University of Vienna 2013, Full text online PDF, free of charge, 206 MB).

- Margit Feischmidt: Ethnicity as construction and experience, symbolic dispute and everyday culture in Cluj, Transylvania (= time horizons , volume 8), Lit, Münster 2003, ISBN 978-3-8258-6627-3 (dissertation HU Berlin 2002).

Transylvania found its way into literature through Bram Stoker's vampire novel Dracula . The plot of this story is partly set in this region and is based on traditions relating to Prince Vlad III. Drăculea are supposed to turn, but actually have little in common with it.

Web links

- Heinz Heltmann: Transylvania (Romanian Transilvania, Hungarian Erdély)

- Brief history of Transylvania (book)

- Christian Agnethler: An overview of the history of Transylvania: AD 1100–2003 ( Memento from July 17, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- History of the Transylvanian Saxons on the website of the German Forum in Kronstadt .

- All former German locations in Transylvania or Romania . The historical German settlement area in over 1000 aerial photos.

- An outline of Transylvanian-Saxon history.

- Location of historical Transylvania.

- Historical securities from Transylvania, sorted by industry.

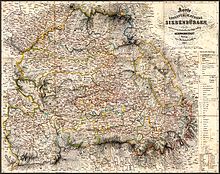

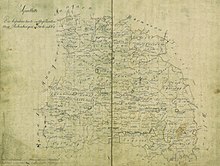

- Historical map of Transylvania around 1750.

- Historical map of Turkey-Hungary with Transylvania 1526–1699.

- Map of the Grand Duchy of Transylvania , 1862.

- Transylvania Institute at Heidelberg University .

- Ethnic map of Transylvania, Banat and Kreischgebiet .

- Seven chairs .

- Audio Atlas Transylvanian-Saxon Dialects (ASD) .

Individual evidence

- ^ Rupprecht Rohr: Small Romanian etymological dictionary: 1. Volume: AB . Keyword: "Ardeal". Haag + Herchen, Frankfurt am Main 1999. page 82.

- ^ Veno Verseck: Romania . 3rd revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 2007. p. 19.

- ↑ Anonymous Gestája, Kiadása: P. magistri, qui dicitur anonymous Gesta Hungarorum. Praefatus est texumque recensuit Aemilius Jakubovich. Annotationes exegeticas adiecit Desiderius Pais . ( Gesta Hungarorum for short ). SRH, Volume IS 32.

- ↑ Harald Roth: Brief history of Transylvania . Böhlau, Köhln / Weimar / Vienna 2003. p. 14f.

- ↑ Armin Hetzer: "Alloglotte speaker groups in the Romance language areas: Südostromania", in: Romance language history . 2nd partial band. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2006. S. 1843.

- ↑ Thomas Nägler: "The name 'Transylvania'". In: Forschungen 12 (1969) 2, pp. 63-71.

- ^ Robert Friedmann: Transylvania . In: Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online

- ↑ The emigration from southern Baden to Transylvania. In: Siebenbürgische Familienforschung, Köln - Wien 1986, 3rd year, No. 2, p. 51 ff. ( Memento from November 29, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Balduin Herter: Baden, Württemberg and the Transylvanian Saxons . ( Memento from August 13, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Transylvanian-Saxon localities: Mühlbach

- ^ Meyers Konversations-Lexikon , 5th edition, 15th volume, Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig and Vienna 1897, p. 996

- ^ Ludwig Albrecht Gebhardi : History of the Grand Duchy of Transylvania and the Kingdoms of Gallicia, Lodomeria and Rothreussen . Pest 1808, p. 3.

- ↑ ( page no longer available , search in web archives: State Government Gazette for the Grand Duchy of Transylvania 1850-1859 ) in Hungarian, German and Romanian.

- ↑ General German newspaper for Romania online from April 24, 2009 , accessed on April 25, 2009.

- ↑ In the Karlsburger decisions the Romanians guaranteed the Magyars and the Germans as minorities extensive equality, but did not comply with this later.

- ^ Johannis wins presidential election. In: Die Zeit vom November 17, 2014, accessed on November 27, 2014.

- ↑ Árpád Varga E., Hungarians in Transylvania between 1870 and 1995 , original title: Erdély magyar népessége 1870–1995 között , Magyar Kisebbség 3–4, 1998 (New series IV), pp. 331–407. Translation by Tamás Sályi, Teleki László Foundation, Budapest, 1999

- ↑ a b Erich Türk: A veritable “organ museum”. The organ landscape of Northern Transylvania between cosmopolitanism and provinciality . In: Organ Journal (1) . Schott, Mainz 2013, p. 21-23 .

- ↑ Ten years of training as a Swiss organ builder in Honigberg . ( Memento from April 29, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) In: evang.ro

- ^ Organ file of the Evangelical Church AB in Romania

- ↑ Allgemeine Deutsche Zeitung of September 28, 2014

- ^ Fundatia Michael Schmidt

- ↑ Organs in Transylvania (YouTube)

- ^ Biodiversity conservation and community development in Transylvania

- ↑ Modern EU agriculture also endangers biodiversity in the accession countries , on May 27, 2011 at agrar-presseportal.de

- ↑ Information on Jenő Dsida from mek.oszk.hu accessed on January 20, 2015 (Hungarian)

- ↑ Information on Zsigmond Kemény from mek.oszk.hu accessed on January 20, 2015 (Hungarian)

- ↑ Áron Tamási from pim.hu accessed on January 20, 2015 (Hungarian)

- ↑ Information on Franz Karl Herfurth at biographien.ac.at