Moravia

Moravia (rarely also Moravia ; from Czech , Slovak Morava [ ] or Latin Moravia ) is (next to Bohemia and Austrian-Silesia or Czech-Silesia ) one of the three historical countries of the Czech Republic , located in its east and south-east . In the 9th century Moravia (as well as the adjacent western parts of Slovakia ) was the core area of the Moravian Empire . At the beginning of the 11th century Moravia became one Country of the Bohemian Crown . As the Margraviate of Moravia , the area was administered as part of the Habsburg Monarchy for centuries . In the Czech Republic, to which it belongs today, Moravia is a historical landscape , provides since 1949 thus no separate administrative unit longer represents.

The indigenous name of Moravia, Morava , originates from that of the main flow of the area, the Danube creek March (Czech / Slovak Morava ).

On its western flank, Moravia is bordered by Bohemia , the largest historical country in the Czech Republic, and on its northern flank by Czech Silesia , the smallest historical Czech country. Moravia borders Slovakia to the east and Austria to the south .

geography

Moravia forms the eastern third of the Czech Republic. The source areas of the Oder from Krnov and Opava towards Ostrava , which historically belong to the Czech part of Silesia, do not belong to the actual Moravia .

The Statistical Yearbook of the Austrian Monarchy for the year 1864 gives an area of 403.77 geographic square miles for the country of Moravia , which corresponds to 22,233 km².

Moravia borders in the north on Poland and the Czech part of Silesia , in the east on Slovakia, in the south on Lower Austria and in the west on Bohemia. The northern border is formed by the Sudetes , which merge into the Carpathian Mountains to the east and south-east . The historical triangle with Bohemia and Austria is located at the top of the Bohemian Saß am Hohen Stein near Staré Město pod Landštejnem ( Dreiländerstein ). The strongly meandering Thaya flows on the border with Austria ; The bilateral Thayatal National Park is located in the vicinity of Hardegg .

The core of the country (altitude 180–250 m) is formed by the sedimentary basin of the March and partly the Thaya. In the west ( Bohemian-Moravian Highlands ) the land rises to over 800 m, but the highest mountain is Altvater (1490 m) in the north-west in the Sudetes. To the south of it lies the Lower Jeseníky highlands (600–400 m), which sinks to 310 m as far as the upper reaches of the Oder ( Moravian Gate near Hranice na Moravě ) and continues to rise to the Beskids at 1,322 m ( Kahlberg ). These three mountain ranges, with the gate between the last two, are part of the European watershed . The eastern border is formed by the White Carpathians with a maximum of 970 m nm ( Velká Javořina ).

population

Some of the Moravians consider themselves an independent ethnic group with Czech citizenship. According to the last survey in 2011, 630,897 people profess the Moravian people (108,423 of them in a linguistic combination, the majority as "Moravian-Czech"). There are also Roma , Slovaks and the long-established Poles . Almost all members of these ethnic minorities have Czech citizenship.

Until 1945 the population of Moravia consisted of a little more than a quarter of German Moravians . According to the results of the Austro-Hungarian census of 1910, the Czech share of the then total population of Moravia (2,622,000 inhabitants) was 71.8% and the German population was 27.6%. The German Moravians were largely expropriated and expelled in 1945/46 as a result of the so-called Beneš decrees .

language

In the colloquial language of Moravia, a distinction is made between various dialects, which differ characteristically from the Bohemian dialects or from the written Czech language.

Ethnographic areas

- Moravian Horakland ( Horácko )

- Thayaland ( Podyjí )

- Brno Surroundings ( Brněnsko )

- Hanna ( Haná )

- Lachei ( Lašsko )

- Moravian Slovakia ( Moravské Slovácko )

- Moravian Wallachia ( Valašsko )

- Kuhländchen ( Kravařsko )

- Schönhengstgau ( Hřebečsko )

history

prehistory

An essential aspect that largely dominated the changes in living conditions in Central Europe was the great expansion phases of the glaciers, which are known as ice or cold ages. During the long cold phases, Moravia lay on the edge of a corridor between Asia and Western Europe that was still difficult to live in, a tundra-like area by today's standards in which the hunting of big game dominated. At the same time, Moravia represented a connection between today's Poland, particularly Silesia , and Lower Austria in the less cold phases . Archaeological research began in 1867.

Early Paleolithic

The oldest ancient Paleolithic site in Moravia is Stránská skála near Brno , which is assigned to the Cromer warm period , which is dated to 850,000 to 475,000 years ago. However, the status of the stone tools as artefacts is partly controversial, so that the presence of humans at this time can only be assumed.

Middle Paleolithic

On the other hand, settlement in the Middle Paleolithic , namely in the Saale glacial period , more precisely in the Intra-Saale interglacial (around 200,000 years ago) is considered certain . Initially, the camps were mostly outdoors, and it was only at the beginning of the Würm glacial period , around 115,000 years ago, that people retreated into caves. The Kúlna Cave and the Moravský Krumlov Cave were inhabited for a long time . The tools discovered there belong to the Taubachian , Moustérien and Micoquien industries . From the Middle Paleolithic there are first indications of raw materials that came from a greater distance and that indicate non-utilitarian activities (paint residues, symmetrical engravings or a hand ax made of rock crystal). At the transition from the Middle to the Upper Palaeolithic, there are two industries that were particularly found in Moravia: the Szeletien , which was dated to 40,000–35,000 BP in Vedrovice , and the Bohunicien from Stránská skála (43,000–35,000 BC).

Layers 3 and 4 in the Šipka Cave are also assigned to the Middle Paleolithic . The Šipka lower jaw discovered in this cave in 1880, the remains of an approximately ten-year-old child, is assigned to the late Neanderthal . It has been dated to be older than 40,000 BP . Traces of the Neanderthal man have also been discovered in the Kúlna cave. The lower jaw of Ochoz, discovered in 1905, was also classified in this epoch, although Šipka and Ochoz show signs that may indicate anatomically modern humans ( Homo sapiens ).

Upper Paleolithic

The first archaeological culture of the hunters and gatherers who immigrated from Africa, known as Homo sapiens , also shows that they were widely involved in exchange relationships. At the same time, regional peculiarities formed, which earned the devices of the time the designation Morava River type (Klima, 1978) or Miškovice type (Oliva, 1990). The concentration of sites in Moravia is unusually high, but it occurred comparatively late and probably initially in interaction with the Neanderthal culture of Szeletia . Realistic representations of animals were first created in the Aurignacien.

Numerous works of art have been preserved from Gravettia , which in Moravia is called Padovia , which at the same time represent works of the symbolic sphere. Two crossed fox teeth were placed on the head of the Dolní Věstonice child. In addition, they found sets decorated cylinders and platelets in Dolní Věstonice I, double pearl in Předmostí and Pavlov, as well as finely carved rings, finger rings, perhaps, in Pavlov I . In addition, some artefacts were given the status of works of art, such as the zoomorphic discs with openings, moon-shaped pendants, fibulae and so-called “headbands” from Pavlov, or ornate pendants from Předmostí. Overall, such works of art were only found in Předmostí, Dolní Věstonice I, Pavlov I and Petřkovice I. Thereby extensive exchange relationships could be proven. In Dolní Věstonice, Cherts were found that came from a mining site in southern Poland, 180 km away, and obsidian from a Hungarian site 500 km away was found in Moravia.

Moravia has peculiarities of eastern Gravettia, but also peculiarities such as the aforementioned headbands or figurines such as the Venus of Věstonice , whose style only appears there. Numerous figurines made of fired clay can only be found in Dolní Věstonice I and Pavlov I. A very complex engraving on the mammoth tusk from Pavlov was interpreted by Bohuslav Klìma as a kind of "map" of the landscape under the Pollau Mountains , but this has been questioned. In the animal representations, mammoths or horses are shown, but never hares, wild boars or bovids, which represented the most important hunting animals. In the remains of a hut one found false fires of figurines; Similar findings came to light in Alberndorf, Lower Austria . Apparently burned animal and woman figurines only occurred northeast of the Alps. These are the oldest ceramic pieces known to man. When burned at 500 to 800 ° C, they were apparently ritually broken.

Moravia is located on the eastern edge of the Magdalenian complex, its sites are concentrated in the caves of the Moravian Karst. There are 25 known sites in Moravia (as of 2016), above all the Pekárna cave ( layers G and H, 12,940 ± 250 BP and 12,670 ± 80 BP). The number of artifacts considered as works of art is small and limited to five sites. Jewelry made of shells, pierced animal teeth, bones, stone and lignite occurs in Moravia as well as in other areas of the hunter-gatherer cultures. Engravings were found on bones, antlers, slate and, in exceptional cases, mammoth ivory, mostly depictions of horses, bison, bears, reindeer and saiga antelopes. Depictions of very common small animal prey are rare, but also depictions of plants and women, the latter in very rare cases as figurines (Pekárna cave), which are then more geometrically laid out, an element that also appears in slate engravings. There are similarities with the depictions of women at the Gönnersdorf site (Lalinde-Gönnersdorf type), but also with finds from the Danube region. They are headless and footless, often worked in the form of pendants.

Neolithic

In Moravia from around 5700 BC For the first time BC peasant cultures, which are assigned to the linear ceramic band (up to 4900 BC). This was followed by stitch band ceramics (4900-4700 BC), then the so-called Moravian painted ceramic culture (4700-4000 BC), a group of the overarching Lengyel culture . In 2008, more than 300 Neolithic settlements were known in Moravia.

The earliest Neolithic offers the greatest density of finds with quite large cemeteries (Vedrovice– Široká u lesa and Za Dvorem or Kralice na Hané– Kralický háj ), burial groups within settlements, but also isolated individual graves (Brno– Starý Lískovec , Nový Lískovec , Bohunice ) , Burial forms associated with rural culture. In Široká u lesa , women accounted for 45% of the 81 deaths, and 30% for men. In cemeteries of ceramics, the proportion of men and women was 25% each. Linear ceramic men were about 1.65 m tall, the women 1.55 m. The stitch band ceramists were about two centimeters shorter. The men of the Lengyel culture were on average 162.1 cm tall, the women were 153.3 cm. Most of the Neolithic individuals were 20 to 35 years old; Signs of prolonged periods of malnutrition were evident. The consequences of hard or one-sided physical work could also be seen on the skeleton.

Metal age

Moravia developed on both sides of the Amber Road in prehistoric times . Around 60 BC The Celtic Boier withdrew from the area and were replaced by Germanic Marcomanni and Quadi , who moved on to the foothills of the Alps with the Rugians around 550 AD .

Middle Ages and Early Modern Times

Great Moravian Empire

The Slavic Moravians settled the region in the 6th century . In the 7th century, Moravia was part of the Samo Empire . At the beginning of the 8th century, the southern part was under the influence of the Avars . After Charlemagne had expelled the Avars, the Moravian Principality emerged towards the end of the 8th century in what is now southeastern Moravia, parts of southwestern Slovakia ( Záhorie ) and later in parts of Lower Austria . With the conquest of the Principality of Nitra (present-day Slovakia and parts of northern Hungary) in 833, it became the Empire of Greater Moravia , which later also ruled various large neighboring areas (parts of Bohemia , Hungary , the Vistula region, etc.). In 863 the Moravian ruler Rastislav summoned the two Byzantine monks Cyril and Method , who introduced Christianity .

The Great Moravian Empire was defeated around 907 in the fight against the invading Hungarians. Today's Slovakia was incorporated into the Hungarian principality (later kingdom) ruled by the Arpad dynasty and remained a land of St. Stephen's Crown until 1918 under the name of Upper Hungary .

Under bohemian power

Today's Moravia was still independent for a short time after the devastating defeat against the Hungarians and came under Bohemian sovereignty around 955. After being ruled briefly by Poland's ruler Boleslaw Chrobry from 999 to 1019 , Moravia finally became Bohemian in 1031. The principality and later Kingdom of Bohemia was ruled by the Přemyslid dynasty until it died out in the male line in 1305 (murder of King Václav III ). For a long time there were three regional principalities in Moravia, the rulers of which all came from the Přemyslid dynasty. The centers of these principalities were Brno ( Brno ), Olomouc ( Olomouc ) and Znojmo ( Znojmo ).

Moravian history has been parallel to the history of Bohemia almost continuously since 1031. In 1182 Moravia was raised to margraviate and thus immediately under the rule of the empire , but in 1197 it was again subject to the Bohemian fiefdom . After the Přemyslids died out, the kingdom was ruled by the House of Luxembourg until 1437 . The Přemyslid and Luxembourg dynasties also included the Moravian margraves, so u. a. the later King Ottokar II. Přemysl , the later King and Emperor Charles IV. and his nephew, the largely independent Margrave Jobst of Moravia . During the eventful Hussite period , most of the Moravian nobles remained faithful to the Catholic faith and to the Bohemian and Hungarian king and later emperor Sigismund of Luxembourg .

Even during the reign of the underage Bohemian King Ladislaus Postumus (a Habsburg , 1440-1457) and the reign and subsequent reign of the utraquist King George of Podebrady (1420-1471), Moravia remained more on the Catholic side.

In 1469, the Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus advanced with his armed forces to Moravia to overthrow his father-in-law Georg von Podiebrad, whose daughter Katharina he married in 1461, as King of Bohemia. At the request of the Grünberger Alliance , he was elected Bohemian rival king in Olomouc in 1469. Pope Paul II supported his struggle against the Turks and the Bohemian "heretics". The sudden death of Podiebrad in 1471 came to Matthias Corvinus' help in achieving his goals. Matthias could never conquer the actual Bohemia, his rule only extended over the Bohemian neighboring countries Moravia, Silesia (with Breslau ), Upper and Lower Lusatia . Nevertheless, he called himself King of Bohemia from 1469 and was crowned in 1471. The struggle for the Bohemian throne was not ended until 1479 with the Peace of Olomouc , in which the Kingdom of Bohemia was temporarily divided between Vladislav II and Matthias Corvinus. In Bohemia itself, Vladislav II Jagellonský, who was elected by the local estates and who was later to succeed Matthias Corvinus in Hungary, asserted himself.

It was still the far-sighted George of Podebrady who paved the way to the Bohemian throne for the two Jagiellonians , the kings Vladislav II and his son Ludwig Jagellonský . After the long years of the rule of Vladislav II, however, the sudden death (drowning in a river) of Ludwig II came after the defeat of the Hungarian army in the battle of Mohács (1526) against the Ottomans . On the basis of the previously concluded treaties, the House of Habsburg now assumed power in the Kingdom of Bohemia with all its neighboring countries as well as in Hungary. The Kingdom of Bohemia and with it the Margraviate of Moravia were ruled almost continuously from this house until 1918. Initially, Prague was still an effective seat of government, especially during the time of King and Emperor Rudolf II , who himself resided in Prague. After 1621, most of the Bohemian and Moravian government were relocated to Vienna .

Anabaptist Movement and Lutherans, Catholic Reform, Jewish Policy

As early as 1526, one of the first communities of property of the radical Reformation Anabaptist movement was formed in the Nikolsburg area around Balthasar Hubmaier . The impending dissolution of the Anabaptist community after the execution of Hubmaier in 1528 was prevented by Jakob Hutter , who came from Tyrol . The Anabaptists were also called Hutterite Brothers after him . Up to 60,000 Anabaptists lived in Moravia, 12,000 of them in Nikolsburg. Shortly after the Anabaptists and supported by the local nobility, the Reformation teachings of Martin Luther also found their way into South Moravia. The church split into Catholics and the Evangelical Lutheran and other churches.

During the Catholic Reform and Recatholization , which were carried out by the Jesuits in particular , many churches were able to be consecrated as Catholics again. After the persecution of the Anabaptists in Moravia from 1535 to 1767 by Catholics, Protestants and Turks, a remnant fled to Russia.

Emperor Charles VI. 1726 set the maximum number of Jewish families for all of Moravia at 5,106. Jewish marriages were only permitted in such a way that only the eldest son could enter into a valid marriage after the death of the father. At the same time, the Jewish population was separated from the Christian population and their own Jewish quarters were systematically set up. In some places entire streets and parts of the city were only inhabited by Jews, a cornerstone for the Jewish communities.

The capital of Moravia and the seat of the margraves was the centrally located Olomouc from the rule of the Luxembourgers until 1641 . After that, the larger Brno became the capital of the country.

19th century

As the margraviate of Moravia , it formed its own crown land in the Austrian Empire and, from 1867, in the western half of Austria-Hungary . After Hungary left the empire and the real union Austria-Hungary was created in 1867, the remaining crown lands were officially referred to as Cisleithania or the kingdoms and countries represented in the Imperial Council .

Moravia elected members of the Vienna Reichsrat and had its own parliament and a regional government called a regional committee. In 1905 a compromise was made between the two strongest ethnic groups in Moravia, which went down in history as the Moravian Compromise , according to which the members of the German and Czech state parliament were elected in ethnically separate constituencies . This compromise aimed at a conflict-free coexistence of the two peoples in Moravia in the sense of a desired Austro-Czech balance . Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk said:

"My homeland was never as happy as when it was part of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy."

Czechoslovakia from 1918 to 1992

With the establishment of Czechoslovakia on October 28, 1918, Moravia became part of the new state, which on the one hand saw itself as the successor state of the Kingdom of Bohemia with its neighboring countries, and on the other hand had the idea of Czechoslovakism in the cradle. In its border areas, however, the German-speaking population initially made efforts to separate these regions from Czechoslovakia and to the neighboring states, i. H. to join the German Empire and the Republic of Austria ( German Austria ). All of these areas, including the South Moravian areas populated by German Moravians, were quickly occupied by Czechoslovak troops. Participation in the election of the Constituent National Assembly of German Austria in early 1919 was prevented by the Czechoslovak Republic in South Moravia. Ultimately, the hope that the right of peoples to self-determination promoted by US President Woodrow Wilson would prevail in the peace negotiations of 1919 (see: Peace Treaty of Saint-Germain ) in favor of the German South Moravians. The efforts to enlarge the territory of the Republic of Austria de facto to include historical areas of Moravia were hostile to the two European victorious powers, the United Kingdom and especially France .

In the Czechoslovak Republic, Moravia retained its position as a country. The western part of Czechoslovakia was formed by the predominantly Czech-populated countries of Bohemia and Moravia, whose border areas, however, had a high proportion of German-Bohemian and German-Moravians, as well as the country of Moravian-Silesia , which is predominantly populated by German-speaking people . The area of the last-mentioned, relatively small country corresponded to the majority of the former Austrian Silesia . Moravian Silesia, in which many ethnic Czechs and Poles also lived, was incorporated into the Moravian regional administration after a few years. The German-speaking population of Bohemia, Moravia and Moravian-Silesia as well as Slovakia received, like most of the other inhabitants who did not belong to the officially proclaimed Czechoslovak people , the Czechoslovak citizenship. The German-speaking population remained largely intact in numbers until they were expelled (so-called odsun ) in 1945 and 1946. There are still controversial judgments about their civil, cultural and other rights and their protection in the so-called First Czechoslovak Republic.

time of the nationalsocialism

During the Nazi era , on October 1, 1938, due to the Munich Agreement concluded at the expense of Czechoslovakia, predominantly German-populated areas in north and south Moravia were transferred to the German Reich and were occupied by the military until October 10. These areas were then (and are often also today in the literature outside of the Czech Republic) subsumed together with the German-populated peripheral areas of Bohemia under the term Sudetenland . The remaining areas of Bohemia and Moravia, which were predominantly populated by Czechs, were occupied by the German Wehrmacht on March 15, 1939 and declared a Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia by Nazi Germany .

On April 14, 1939, the north Moravian annexation area was assigned to the newly formed Reichsgau Sudetenland . The South Moravian area was added to the Reichsgau Niederdonau , the former Lower Austria. In the north-east of the Czechoslovakian country of Moravia-Silesia, a small part of the area ( Olsa area ) , which historically belonged to Austrian Silesia, was attached to Poland in 1938 , and after its occupation in the autumn of 1939, to German Upper Silesia . The Sudeten Germans and German Moravians had been German citizens since 1938 through collective naturalization . and had to serve in the armed forces; In 1945, among other things, this served as an argument for their expulsion .

The Moravian resources and industries were used for the German war economy. After the war, the Czech population was to be partly Germanized and partly resettled. The Czech Protectorate Government in Prague was completely dependent on the "Reich Protector", as the top German functionary in the area was called. Even before the assassination attempt on the deputy Reich Protector Reinhard Heydrich , very repressive measures were taken against the Czech population of the Protectorate. After this successful assassination attempt, several hundred people throughout the protectorate who were unrelated to the assassination attempt were illegally sentenced to death and executed.

The Czech universities and colleges in the entire Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia were banned and dissolved by the occupying powers as early as 1939. The Czech grammar schools and other educational institutions below the university level were allowed to remain in existence until 1945. On the other hand, z. B. the German Technical University of Brno during the entire protectorate period up to 1945.

After 1945

After the Second World War on 8 May 1945 were caused by the Munich Agreement of 1938 to the German Reich back (or 1938 to Poland and then in 1939 to the German Reich) came territories back to Czechoslovakia.

In 1945 and 1946 the tension between the Czech and German populations, which had grown steadily during the protectorate period, was released. Except for a relatively small number of people, such as in ethnically mixed marriages or important professions that German Moravian citizens, starting already in mid-May 1945, both spontaneous and intentional wild across the border into Austria and Germany expelled . Others fled from the abuse and violence . On August 2, 1945, the Allies did not take a specific position in the Potsdam Protocol , Article XIII, on the wild and collective expulsions of the German population. However, they explicitly called for an "orderly and humane transfer" of the "German population segments" that "remained in Czechoslovakia". Between February and October 1946 the official, orderly and humane forced evacuation of the German citizens from Moravia took place. In Francis E. Walter's report to the House of Representatives, it was noted that the transports were by no means in accordance with this provision. All private and public property of the German Moravians was confiscated by the Beneš Decree No. 108 , the property of the German Evangelical Church was liquidated by the Beneš Decree No. 131.

The number of expellees whose names and fate are known is given as 637 people for South Moravia. Furthermore, the “ Brno Death March ” (May 30, 1945) claimed the lives of between 1,700 and 5,200 people, at least 890 of them are said to have died in the Pohořelice camp . A legal processing of the event has not taken place. The Beneš Decree No. 115/1946 declared actions committed in the struggle to regain freedom ... or which aimed at just retaliation for acts of the occupiers or their accomplices ... not unlawful until October 28, 1945 .

The members of the German minority in the Czech Republic who still live in Moravia today , for whom the umbrella term Sudeten Germans is often used, often do not identify themselves with this name.

The Roman Catholic Church , which was run exclusively by the Czech clergy after 1945, was largely expropriated in all parts of Czechoslovakia during the communist era . The Czech Republic has not yet made any compensation for their property. However, after long parliamentary deliberations, it was enshrined in law in 2013 for all recognized ecclesiastical communities, so that the return of the confiscated property of the churches is often expected.

Since January 1, 1993, Moravia has been an integral part of the Czech Republic , one of the two successor states of the Czechoslovak Federal Republic , which was dissolved by mutual agreement and under international law at the end of 1992 .

Administrative division

Old Moravian Districts

The Bohemian king , who was also Margrave of Moravia and Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV, began dividing his kingdom into large administrative units in the middle of the 14th century. Such an administrative unit was called in the documents in German circle , in Czech kraj and in Latin circulus . There were between two and six such circles in Moravia.

The number of circles and thus their size changed several times. This district division was in place until 1862, but shortly after the revolution of 1848 it played practically no role in the administration.

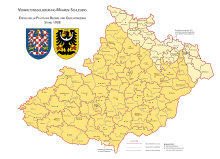

Political and judicial districts from 1850

From 1850, in all areas of the monarchy except Hungary, the old large districts were replaced by political districts (the executive), each of which consisted of one or more judicial districts (the judiciary). This classification still exists in the Austrian federal states . Usually a political district (Czech: politický okres ) was smaller than a former old district, and a judicial district (Czech: soudní okres ) is smaller than a political district. Moravia had 32 political districts.

The following division of districts continued to apply in the First Czechoslovak Republic , apart from minor changes and the creation of three new districts (Bärn, Mährisch Ostrau and Wesetin) :

| German name | Czech name | Administrative unit | Judicial district (s) | Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auspitz | Hustopeče | political district | Auspitz , Klobouk , Seelowitz | 1862-1938 |

| Boskowitz | Boskovice | political district | Blanz , Boskowitz , Kunstadt | 1862-1938 |

| Brno | Brno | political district | Brno , Eibenschütz | 1862-1938 |

| Datschitz | Dačice | political district | Datschitz , Telsch | 1862-1938 |

| Gaya | Kyjov | political district | Gaya , Steinitz | 1862-1938 |

| Goeding | Hodonín | political district | Göding , Lundenburg , Strasbourg | 1862-1938 |

| Great Meseritsch | Velké Meziříčí | political district | Groß Bittesch , Groß Meseritsch | 1862-1938 |

| Hohenstadt | Zábřeh | political district | Hohenstadt , Müglitz , Schildberg | 1862-1938 |

| Holleschau | Holešov | political district | Bystritz a. H. , Holleschau , Wisowitz | 1862-1938 |

| Iglau | Jihlava | political district | Iglau | 1862-1938 |

| Kremsier | Kroměříž | political district | Kremsier , Zdounek | 1862-1938 |

| Littau | Litovel | political district | Konitz , Littau | 1862-1938 |

| Moravian Budwitz | Moravské Budějovice | political district | Jamnitz , Mährisch Budwitz | 1896-1938 |

| Moravian Kromau | Moravský Krumlov | political district | Hrottowitz , Moravian Kromau | 1862-1938 |

| Moravian Schönberg | Šumperk | political district | Moravian old town , Mährisch Schönberg , Wiesenberg | 1862-1938 |

| Moravian Trübau | Moravská Třebová | political district | Gewitsch , Mährisch Trübau , Zwittau | 1862-1938 |

| Moravian Weisskirchen | Hranice na Moravě | political district | Leipnik , Mährisch Weißkirchen | 1862-1938 |

| Mistek | Místek | political district | Frankstadt , Mistek | 1862-1938 |

| Neustadtl in Moravia | Nové Město na Moravě | political district | Bistritz ob Pernstein , Neustadtl in Moravia , Saar | 1862-1938 |

| Neutitschein | Nový Jičín | political district | Freiberg , Fulnek , Neutitschein | 1862-1938 |

| Nikolsburg | Mikulov na Morave | political district | Nikolsburg , Pohrlitz | 1862-1938 |

| Olomouc | Olomouc | political district | Olomouc | 1862-1938 |

| Prerau | Přerov | political district | Kojetein , Prerau | 1862-1938 |

| Prossnitz | Prostějov | political district | Plumenau , Prossnitz | 1862-1938 |

| Roman city | Rýmařov | political district | Roman city | 1862-1938 |

| Sternberg | Šternberk | political district | Moravian Neustadt , Sternberg | 1862-1938 |

| Tischnowitz | Tišnov | political district | Tischnowitz | 1862-1938 |

| Trebitsch | Třebíč | political district | Namiest on the Oslawa , Trebitsch | 1862-1938 |

| Hungarian Brod | Uherský Brod | political district | Bojkowitz , Hungarian Brod , Wall. Klobouk | 1862-1938 |

| Hungarian Hradish | Uherské Hradiště | political district | Napajedl , Hungarian Hradisch , Hungarian Ostra | 1862-1938 |

| Wallachian Meseritsch | Valašské Meziříčí | political district | Rosenau under the Radhoscht , Wallachian Meseritsch | 1862-1938 |

| Wischau | Vyškov | political district | Austerlitz , Butschowitz , Wischau | 1862-1938 |

| Znojmo | Znojmo vankov | political district | Frain , Joslowitz , Znaim | 1862-1938 |

| Brno | Brno-město | Statutory city | Brno | 1862-1938 |

| Iglau | Jihlava | Statutory city | Iglau | 1862-1938 |

| Kremsier | Kroměříž | Statutory city | Kremsier | 1862-1938 |

| Olomouc | Olomouc | Statutory city | Olomouc | 1862-1938 |

| Hungarian Hradish | Uherské Hradiště | Statutory city | Hungarian Hradish | 1862-1938 |

| Znojmo | Znojmo | Statutory city | Znojmo | 1862-1938 |

| Bear | Moravský Beroun | political district | Hof , City of Liebau | 1920-1938 |

| Moravian Ostrava | Ostrava | political district | Moravian Ostrava | 1920-1938 |

| Wesetin | Vsetín | political district | Wesetin | 1920-1938 |

For the simultaneous development in Bohemia and Slovakia, see Okres .

Counties and districts under German occupation

Due to the Munich Agreement of September 29, 1938, the predominantly German-speaking part of northern Moravia was added to the Reichsgau Sudetenland of the German Reich , and southern Moravian areas with a German majority were incorporated into the Reichsgau Niederdonau . The annexed area was divided into urban and rural districts; overriding were administrative districts . The remaining part of Moravia in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia remained divided into political districts and judicial districts, although an Oberlandrats district was introduced over each group of political districts.

In the entire Reichsgau Sudetenland there were five urban districts and 52 rural districts. There were 67 Czech and 30 Moravian political districts in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. This administrative structure was in place until the end of the Second World War .

Current state

The areas of today's Czech Okresy (these were formally dissolved and only play a role in the NUTS breakdown) and Kraje only partially reflect the areas of the historical countries. From a historical point of view, some districts include both Moravian and Silesian areas or, in many cases, Moravian and Bohemian areas. Today, historical Moravia is divided into the following districts (from west to east and north to south): Eastern part of Pardubice District , southeast part of South Bohemian District , eastern half of Vysočina District , entire South Moravian District , majority of Olomouc District , parts of Moravian - Silesian District as well as the entire Zlín District .

economy

In the south near Hodonín and Břeclav , Moravia has a share in the Vienna Basin , in the deeper sediments of which drilling is carried out for oil , natural gas and lignite . It gave the Moravic its geological name. In Ostrava (northeast) hard coal was mined intensively until around 1995 .

The iron and steel industry , mechanical engineering , chemical industry and the manufacture of clothing, leather and building materials are important branches of industry in Moravia . Important economic centers are Brno (formerly called Moravian Manchester ), Olomouc , Ostrava and Zlín . The modern city of Zlín was shaped by the Tomáš Baťa works in the first half of the 20th century . The north Moravian heavy industry and mining area was already one of the most important industrial regions in Europe at the time of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. In one of the most modern car factories in the world, located in the Nošovice industrial zone ( Frýdek-Místek district ), passenger cars for the Korean Hyundai Motor Company have been manufactured since September 2009, mainly for export to Western European markets.

Since the extensive privatizations and restitutions of the early 1990s, the economy of the Czech Republic and thus also Moravia has been organized almost exclusively on the private sector. It is primarily geared towards the markets in the European Union , of which a considerable part is directed towards the markets of Germany and Austria . This is also due to the fact that numerous companies are owned by companies from EU countries.

In addition to the intensive, partly large-scale agriculture (grain, rape, sugar beet, etc.) in the Hanna (Moravia) region , in Moravian Slovakia and in other regions, Moravia is known for its viticulture and fruit and vegetable growing . The South Moravian wine-growing region produces around 90% of the wine produced in the Czech Republic. In the past 23 years, i. H. Since the privatization of the entire economy, great advances have been made in viticulture with regard to the quality of the mainly white and red wines produced.

See also

- List of Moravian rulers

- List of judicial divisions in Moravia

- Moravian State Library in Brno

- Moravian State Museum in Brno

- Moravian-Silesian Museum in Klosterneuburg

- Moravian eagle

literature

prehistory

- Martin Oliva: Art and jewelry of Gravettien in Moravia , in: Leif Steguweit (Hrsg.): People of the Ice Age. Jäger - Handwerker - Künstler , Erlangen 2008, pp. 60–73.

- Martina Lázničková-Galetová: The Magdalenian art in Moravia , in: Leif Steguweit (Hrsg.): People of the Ice Age. Jäger - Handwerker - Künstler , Erlangen 2008, pp. 74–81.

- history

- Manfred Alexander: Small history of the bohemian countries . Reclam, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-15-010655-6 ( table of contents [PDF; 288 kB ] current overview).

-

Karl Bosl , Karl Richter, Gerhard Mildenberger , Ferdinand Seibt , Heribert Sturm , Gerhard Hanke and others. a .: Handbook of the History of the Bohemian Lands . Ed .: Karl Bosl. 4 volumes. Anton Hiersemann Verlag, Stuttgart, ISBN 978-3-7772-6602-2 ( table of contents - former standard work, based on the research status of the 1960s).

- Volume 1: The Bohemian Lands from the Archaic Period to the Outcome of the Hussite Revolution in 1967. 1967, OCLC 873270139 .

- Volume 2: The Bohemian countries from the heyday of the class rule to the awakening of a modern national consciousness. 1974, ISBN 3-7772-7414-3 .

- Volume 3: Bourgeois Nationalism and Formation of an Industrial Society 1968. 1967/68, OCLC 873270172 .

- Volume 4: The Czechoslovak state in the age of modern mass democracy and dictatorship. 1970, ISBN 3-7772-7012-1 .

- Jan Filip : Bohemia and Moravia. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 3, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1978, ISBN 3-11-006512-6 , pp. 129–157.

- Jutta Franke, Reiner Franke, Eva Schmidt-Hartmann u. a .: Biographical lexicon on the history of the Bohemian countries . Ed .: Heribert Sturm , Ferdinand Seibt , Hans Lemberg , Helmut Slapnick, Ralph Melville a. a., Collegium Carolinum . 4 volumes (three published so far). Oldenbourg, Munich ( collegium-carolinum.de [PDF] partial directory).

- Volume 1: A-H. 1979, ISBN 3-486-49491-0 .

- Volume 2: I-M. 1984, ISBN 3-486-52551-4 .

- Volume 3: N-Sch. 2000, ISBN 3-486-55973-7 .

- Volume 4: Sci-Z.

- Heribert Sturm , Collegium Carolinum (Hrsg.): Ortlexikon der Bohemian Lands . Oldenbourg, Munich / Vienna 1983, ISBN 3-486-51761-9 .

- Walter Kosglich, Marek Nekula, Joachim Rogall (eds.): Germans and Czechs. History - Culture - Politics (= Beck's series . No. 1414 ). 2nd revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-45954-4 .

- Jan Křen : The conflict community. Czechs and Germans 1780–1918 . Ed .: Collegium Carolinum (= Publications Collegium Carolinum . No. 71 ). 2nd Edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-486-56449-8 (Czech: Conflictní společenství. Češi a Němci 1780–1918 . Prague 1986. Translated by Peter Heumos, study edition, standard work).

- Lumtr Polaeek: Great Moravian Empire. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 13, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1999, ISBN 3-11-016315-2 , pp. 78-85.

- Friedrich Prinz : German history in Eastern Europe. Bohemia and Moravia . Siedler, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-88680-202-7 (popular science, but on a broad scientific basis).

- Bernd Rill: Bohemia and Moravia. History in the heart of Central Europe . Two volumes. Katz, Gernsbach 2006, ISBN 3-938047-17-8 (detailed, popular science).

- František Josef Schwoy: Topographical description of the Margraviate of Moravia

- Ferdinand Seibt: Germany and the Czechs. History of a neighborhood in the middle of Europe . 3rd updated edition. Piper, Munich / Zurich 1997, ISBN 3-492-21632-3 (Piper series number 1632, standard work on neighborly relations).

- Cultural history

- Ingeborg Fiala-Fürst (Ed.): Lexicon of German-Moravian Authors . Loose-leaf collection , two deliveries so far. Univerzita Palackého, Olomouc.

- Volume 1: (= contributions to Moravian German-language literature. 5). 2002, ISBN 80-244-0477-X .

- Volume 2: Supplements (= contributions to Moravian German-language literature. 7). 2006, ISBN 80-244-1280-2 .

- Jiří Holý: History of Czech Literature in the 20th Century . Edition Praesens, Vienna 2003, ISBN 3-7069-0145-5 (Original title: Dějiny české literatury v 20. století . Translated by Dominique Fliegler and Hanna Vintr).

- Antonín Měšt'an: History of Czech Literature in the 19th and 20th Centuries . In: Building blocks for the history of literature among the Slavs . tape 24 . Böhlau, Cologne / Vienna 1984, ISBN 3-412-01284-X .

- Hugo Rokyta: Moravia and Silesia . In: The Bohemian Lands. Handbook of monuments and memorials of European cultural relations in the Czech lands. Three volumes . 2nd (revised and expanded) edition. Vitalis, Prague 1997, ISBN 80-85938-17-0 .

- Lillian Schacherl: Moravia . Prestel, Munich / New York 1998, ISBN 3-7913-2029-7 (completely revised new edition).

- Walter Schamschula: History of Czech Literature . 3 volumes. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna, OCLC 24037802 .

- Volume 1: From the Beginnings to the Age of Enlightenment. 1990, ISBN 3-412-01590-3 .

- Volume 2: From Romanticism to the First World War. 1996, ISBN 3-412-02795-2 .

- Volume 3: From the founding of the republic to the present. 2004, ISBN 3-412-07495-0 .

- Jiří Sehnal, Rudolf Flotzinger : Moravia. In: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon . Online edition, Vienna 2002 ff., ISBN 3-7001-3077-5 ; Print edition: Volume 3, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-7001-3045-7 .

- Jan Sapák, Stephan Templ : Moravia - buildings, people, roads . Ed .: Adolph Stiller. Salzmann, Salzburg / Vienna 2014, ISBN 978-3-99014-102-1 .

- Jürgen Serke : Bohemian Villages. Walks through an abandoned literary landscape . Zsolnay, Vienna / Hamburg 1987, ISBN 3-552-03926-0 (popular scientific standard work on the German-language literature of the Bohemian countries).

Web links

- State Law and Ordinance Gazette for the Margraviate of Moravia 1849–1918.

- Robert Luft: The limits of regionalism: The example of Moravia in the 19th and 20th centuries. In: Regional movements and regionalisms in European spaces since the middle of the 19th century. [Ed.]: Philipp Ther , Holm Sundhaussen . Herder-Institut, Marburg 2003, pp. 63-88 ( herder-institut.de PDF; 4.3 MB).

Individual evidence

- ↑ K moravské národnosti se při sčítání přihlásilo přes půl milionů lidí na Tiscali.cz ( Memento of the original from December 26, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Hans Chmelar: Highlights of the Austrian emigration. The emigration from the kingdoms and countries represented in the Imperial Council in the years 1905–1914. (= Studies on the History of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. Volume 14) Commission for the History of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1974, ISBN 3-7001-0075-2 , p. 109.

- ↑ Karel Valoch: Palaeolithic archeology in the former Czechoslovakia and its contribution to Central European research , in: Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Urgeschichte 19 (2010) 71–115.

- ↑ Petr Neruda: Neandertálci na Kotouči u Štramberka , Archeologické centrum Olomouc, 2006, p. 64 ( online , PDF).

- ^ Emanuel Vlček: Neanderthals of Czechoslovakia , Academia, 1969, p. 35.

- ↑ On the Paleolithic in Moravia, albeit no longer up-to-date, cf. Jiří Svoboda, Vojen Lozek, Emanuel Vlcek: Hunters between East and West. The Paleolithic of Moravia , Plenum Press, 1996.

- ↑ On the transition phase between the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic cf. Petr Neruda, Zdeňka Nerudová: The Middle-Upper Palaeolithic transition in Moravia in the context of the Middle Danube region , in: Quaternary International 294 (2013) 3–19 (published digitally in 2011).

- ↑ Martin Oliva: Art and jewelry des Gravettien in Moravia , in: Leif Steguweit (Hrsg.): People of the Ice Age. Jäger - Handwerker - Künstler , Erlangen 2008, pp. 60–73, passim.

- ↑ Brooke S. Blades: Aurignacian Lithic Economy. Ecological Perspectives from Southwestern France , Springer, 2006, p. 18 f.

- ↑ Martin Oliva: Art and jewelry des Gravettien in Moravia , in: Leif Steguweit (Hrsg.): People of the Ice Age. Jäger - Handwerker - Künstler , Erlangen 2008, pp. 60–73, here: p. 64.

- ↑ Martin Oliva: Art and jewelry des Gravettien in Moravia , in: Leif Steguweit (Hrsg.): People of the Ice Age. Jäger - Handwerker - Künstler , Erlangen 2008, pp. 60–73, here: p. 65.

- ↑ Hermann Parzinger: The children of Prometheus. A history of humanity before the invention of writing , C. H. Beck, 2015, p. 82.

- ↑ Martina Lázničková-Galetová: The Magdalenian art in Moravia , in: Leif Steguweit (Ed.): People of the Ice Age. Jäger - Handwerker - Künstler , Erlangen 2008, pp. 74–81, here: p. 75.

- ↑ Marta Dočkalová, Zdenék Čižmář: Neolithic settlement burials of adult and juvenile individuals in Moravia (Czech Republic) , in: Anthropologie 46,1 (2008) 37–76, here: p. 38 ( online , PDF).

- ↑ Marta Dočkalová, Zdenék Čižmář: Neolithic settlement burials of adult and juvenile individuals in Moravia (Czech Republic) , in: Anthropologie 46,1 (2008) 37–76, here: pp. 70–74.

- ^ František Palacký: Archive český .

- ^ Anton Kreuzer: History of South Moravia Volume 1. P. 62. Publishing house of the South Moravia Landscape Council Geislingen / Steige. 1997. ISBN 3-927498-20-3 .

- ^ Gregor Wolny : The Anabaptists in Moravia, Vienna 1850.

- ↑ Peter Hoover: Baptism of Fire. The radical life of the Anabaptists - a provocation , Down to Earth, Berlin 2006, ISBN 978-3-935992-23-7 , pp. 20-25 and pp. 161-185

- ^ Jews in Moravia, Jewish communities in South Moravia. Retrieved March 29, 2020 .

- ^ Heinrich von Kadich, Conrad Blažek: Der Moravian Adel , Bauer & Raspe, Nuremberg 1899, p. III f.

- ^ Lothar Selke : The Technical University of Brno and its corporations . Einst und Jetzt , Vol. 44 (1999), p. 106.

- ↑ Detlef Brandes : The way to expulsion 1938-1945. Oldenbourg, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-486-56731-4 .

- ↑ Cornelia Znoy: The expulsion of the Sudeten Germans to Austria 1945/46 , diploma thesis to obtain the master’s degree in philosophy, Faculty of Humanities at the University of Vienna, 1995.

- ^ Charles L. Mee : The Potsdam Conference 1945. The division of the booty . Wilhelm Heyne Verlag, Munich 1979. ISBN 3-453-48060-0 .

- ↑ Emilia Hrabovec: Expulsion and Deportation. Germans in Moravia 1945–1947. Frankfurt am Main / Bern / New York / Vienna (= Vienna Eastern European Studies. Series of publications by the Austrian Institute for Eastern and South Eastern Europe), 1995 and 1996.

- ↑ Mikulov Archives: Odsun Nĕmců - transport odeslaný dne 20. kvĕtna 1946 .

- ↑ Francis E. Walter: expellees and refugees of German ethnic origin. Report of a Special Subcommittee of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, HR 2nd Session, Report No. 1841, Washington March 24, 1950.

- ↑ Ignaz Seidl-Hohenveldern : International Confiscation and Expropriation Law. Series: Contributions to foreign and international private law. Volume 23. Berlin / Tübingen 1952.

- ^ Alfred Schickel, Gerald Frodl: History of South Moravia. Volume III. Maurer, Geislingen / Steige 2001, p. 244, ISBN 3-927498-27-0 , p. 206.

- ^ Alfred Schickel, Gerald Frodl: History of South Moravia . Volume III. Maurer, Geislingen / Steige 2001, ISBN 3-927498-27-0 .

- ↑ Emilia Hrabovec: Expulsion and Deportation. Germans in Moravia 1945–1947 , Frankfurt am Main / Bern / New York / Vienna (= Vienna Eastern European Studies. Series of publications by the Austrian Institute for Eastern and South Eastern Europe), 1995 and 1996.

- ^ Konrad Badenheuer : The Sudeten Germans. An ethnic group in Europe. Sudeten German Council, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-00-021603-9 .