Solothurn

| Solothurn | |

|---|---|

| State : |

|

| Canton : |

|

| District : | Solothurn |

| BFS no. : | 2601 |

| Postal code : | 4500 |

| UN / LOCODE : | CH SOO |

| Coordinates : | 607 573 / 228 576 |

| Height : | 435 m above sea level M. |

| Height range : | 424–500 m above sea level M. |

| Area : | 6.28 km² |

| Residents: | 16,777 (December 31, 2018) |

| Population density : | 2671 inhabitants per km² |

| City President : | Kurt Fluri ( FDP ) |

| Website: | www.stadt-solothurn.ch |

|

Solothurn |

|

| Location of the municipality | |

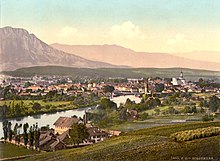

Solothurn (in the local Swiss-German dialect Soledurn [ˈsɔlədʊːrn] or [ˈsɔːlədʊːrn] , French Soleure, Italian Soletta, Rhaeto-Romanic , Latin Salodurum ) is a municipality and the capital of the canton of Solothurn . The city with its almost 17,000 inhabitants forms a district of its own.

Because of the former seat of the French embassy (16-18th centuries), Solothurn is traditionally called the “ambassador city”, and because of its patron saint and the name of the cathedral, it is also called “Sankt-Ursen-Stadt”. Most of the old town in its current state was built between 1520 and 1790 and accordingly shows a mixture of different architectural styles, especially the Baroque, which is why Solothurn is sometimes referred to as the “most beautiful Baroque town in Switzerland”.

geography

Solothurn is 430 m above sea level. M. at the southern foot of the Jura . The city is divided into northern and southern areas by the Aare . The smaller streams include the Brunngraben , Brühlgraben , Obach , Dürrbach and St. Katharinenbach (from west to east). To the north-east of the municipality, the Emme flows into the Aare at Emmenspitz .

From a topographical point of view, the Solothurn old town lies on a terminal moraine of the Rhone Glacier from the Würm glacial period , which is said to have dammed the Solothurnersee after the glacier near Wangen an der Aare had melted . To the north and on the other side of the Aare to the south, the area rises to 470 and 450 m above sea level. M. The community area is 629 hectares large, of which 66% to 1994 settlements, 25% in agriculture and just under 9% to forest trees and unproductive land.

About five kilometers north at 1395 m above sea level. M. is the Solothurn mountain Weissenstein , followed by 2009 from station Oberndorf from the chairlift Oberdorf-Weissenstein led that since December 2014 replaced by a gondola.

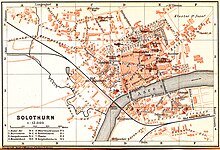

Adjacent communities

Neighboring communities of Solothurn in the West Bellach , north Langendorf and Rüttenen , on the east Feldbrunnen-St. Niklaus and in the south Zuchwil and Biberist . Today the settlement area of Solothurn has grown together almost completely with the development of Bellach, Langendorf, St. Niklaus and Zuchwil.

climate

Climatically, Solothurn is under continental European influence, whereby the parallel constellation Aare - Jura chain results in an above-average number of fog layers .

| Solothurn (Wynau) 1981-2010 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate diagram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Average monthly temperatures and precipitation for Solothurn (Wynau) 1981–2010

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

history

First settlement

In the area of the western old town, two excavations in 1962/63 and 1986 cut a settlement site from the Mesolithic Age . For a long time, the moraine ridge at the eastern end of the flood plain left by the Rhone Glacier offered a nomadic community a suitable resting place, which was abandoned in the early Neolithic .

There are hardly any finds from the Bronze Age and the Pre-Roman Iron Age . In particular, there are no finds from the La Tène period , with the exception of some Häduer coins . Although the place name Solothurn , which is first handed down as vicus Salodurum on an altar stone of the goddess Epona from the year 219 AD , clearly comes from the Celtic language (see following section), no Celtic settlement has been found in today's urban area.

Roman time

The Roman vicus was created on the green meadow during the reign of Tiberius - according to current research between 15 and 25 AD . The establishment of the settlement is likely to be related to the construction of a bridge for the road connection Aventicum - Vindonissa (Avenches-Windisch) and the construction of a simple port facility for shipping on the Aare . The solid banks at the breakthrough of the Aare through the terminal moraine of the Rhone Glacier were ideally suited for the construction of a solid bridge, and the current shadow immediately after this breakthrough for the construction of a landing stage for inland navigation . This view is also supported by the current interpretation of the settlement name: Celtic * Salódŭrōn, formed from the defining word sal "water, wave, surging" and the basic word * dŭrōn "door, gate, fenced in market place", can be translated as "water gate" or else Translate "Marktplatz am Wasser".

The extent of the Vicus Salodurum can only be roughly limited because of the poor archaeological sources. Settlement remains and individual finds from Roman times are concentrated north of the Aare on both sides of today's Hauptgasse, at Stalden and at Friedhofplatz. About 30 meters south of the main street, which leads in a slight curve from the Stalden to the St. Ursenkathedrale , in the courtyard of the Vigierhäuser a bank construction from the year 58 AD could be proven, a good 100 meters from today's bank of the Aare. To the south of it there are no more remains of Roman settlements. Obviously, today's Hauptgasse, the precursor of which may have already opened up the Vicus, follows the Roman bank of the Aare at a constant distance. In the suburb south of the Aare, settlement remains in the area of the Upper Angle were found. The parts of the vicus on both sides of the Aare were connected by a bridge at the site of today's Wengen Bridge or immediately to the west of it. The vicus cemetery was located in the area around St. Ursus Cathedral and in the northern area of the monastery square around St. Peter's Chapel .

Thanks to a considerable number of preserved or documented inscription stones, it is known that the Vicus Salodurum was administered by local chiefs («magistri»). There was a six-man college entrusted with the imperial cult, a Jupiter and a temple of Apollo, and a cult around the horse goddess Epona . The majority of the inscription stones still preserved today were found in 1762 during demolition work in the foundations of the old St. Ursus Cathedral. Today they are exhibited in the stone museum (behind the Jesuit church).

Nothing specific is known about the fate of the vicus in the time of crisis in the late 3rd century. Findings in neighboring villas indicate economic difficulties and a population decline. During the reign of Emperor Constantine , probably between 328 and 337, the remains of the vicus gave way to a castrum . The massive enclosing wall with a thickness of 2 to 3 meters enclosed an area of slightly more than 1.3 hectares and thus only a fraction of the former vicus, the remains of which were provided by the numerous spolia in the foundation area of the castrum wall.

During late antiquity, the city's first church, dedicated to St. Stephen , was built in northern Castrum (today Friedhofplatz) . The Legend of will around the year 300 Christian converted in Solothurn two Roman legionnaires of the Theban Legion have been beheaded: Ursus and Victor . Today's cathedral is named after them. The bones of Victor were transferred to Geneva by the Burgundian princess Sedeleuba in the 5th century , while the Ursus cult lived on in Solothurn.

Carolingians and Zähringer

During the 8th and 9th century Solothurn belonged to the administrative region of Vaud of under the Carolingian standing Frankish Empire . The first known Solothurn coins were minted under the East Carolingian ruler Ludwig IV (900–911).

In 932, the Burgundy Queen Bertha founded the St. Ursenstift at the site of today's St. Ursus Cathedral. Previously, the monastery was located near the bank of the Aare, which was threatened by flooding. During this time, the first city expansion from Castrum eastwards to Schaal- and Judengasse could have taken place. This was followed by the medieval city castle in the area of today's clock tower, naturally protected in the east by the moat of the Goldbach.

In the 11th century, during the reign of the last Burgundian kings , numerous diets were held in Solothurn , while the Stefanskapelle served as the coronation site. Along with Lausanne and Zurich , Solothurn was the only larger city in the Central Plateau .

With the death of Count Rudolf von Rheinfelden in 1080, new noble families moved into the country. Among them the Zähringer were the most important. They not only founded new cities, such as the neighboring cities of Bern and Freiburg , but also expanded numerous others, including Solothurn. In 1127, Duke Konrad von Zähringen received a legacy in the western Swiss plateau. This made the House of Zähringen the leading family in western Switzerland. In Solothurn, the Zähringers seem to have dictated the city constitution , in which the knightly ministerials were given a leading position. But also the rural area around Solothurn came under Zähring rule, for example the Landgraviate of Aarburgund , where counts were employed. In the countryside south of the city, the Lords of Halt , von Balmegg , von Lohn and von Stein bei Aeschi served as the Zähring ministerials .

The Zähringers left the most lasting traces in Solothurn in terms of urban development. The plan of the old town (including the suburb), which is still relatively easy to recognize today, is a result of the Zähringian city expansion, which they marked at the time with the construction of a new fortification wall. Remains of this wall can still be found in the backyard of the Prison House on Prisongasse (today the cantonal office for municipalities) and in the form of towers set into somewhat newer buildings on Nordringstrasse ( Ambassadorenhof and Franciscan monastery , also at Burrisgraben) and Westringstrasse. The lower part of today's clock tower (former market tower ) also comes from the Zähringer era.

So the church town around St. Ursen and the fortified settlement of the Castrum grew together. Gurzelngasse was initially rebuilt as a broad main artery, later Barfüsser-, Hinter- and Eselsgasse, and perhaps also the suburb, were added. This Zähring city wall was the focus of Solothurn life until the beginning of the 19th century.

Solothurn becomes an imperial-free city

After the death of the last, childless Zähringer, Solothurn, like Bern, was declared an imperial- free city in 1218 and henceforth had the status of an imperial city within the Holy Roman Empire . The governor, now called Reichs- Schultheiss , now assumed power (see Solothurn Schultheissen ). The city charter, which was obtained during the city’s continued efforts to achieve autonomy, brought in new funds. They gave Solothurn the opportunity to fortify and beautify the city: in 1230 the suburb (south of the Aare) and in 1296 the Aare bridge is mentioned. In 1280 the Franciscans settled in Solothurn and were able to complete their church in 1299 . The predecessor of today's St. Ursus Cathedral was also built at this time: the Gothic St. Ursen Minster was consecrated in 1294, but both towers fell victim to the Basel earthquake of 1356 and were later replaced by the Wendelstein . At the beginning of the 14th century the Gold- and Schaalgasse, the Eich- and Barfüssertor as well as the Tinkelmanns- and Nideckturm are mentioned in the sources for the first time. In 1378 some alleys were even paved.

Because of the difficult times for imperial-free cities in the 13th century, Solothurn also had to look for allies. In addition to some contracts with individual monasteries, the Berne Federation was concluded, which was to become important for Solothurn in the future. Ultimately, the Confederates of Central Switzerland as well as Solothurn and Bern refused to recognize the Habsburg Frederick the Beautiful . So in 1315 there was the Battle of Morgarten and in 1318 Solothurn was besieged by Friedrich's brother, Duke Leopold I , who, however, was defeated with the help of around 400 Bernese. Leopold, however, is probably due to the Solothurn coat of arms, which is in the cathedral treasury at St. Ursen. The city was also able to form important alliances with Biel (1334), Burgdorf (1377) and other cities and monasteries.

Entry into the Swiss Confederation

1393 began for Solothurn with the Confederates . This year the city was co-signer of the Sempacher letter . Solothurn also took part in the other battles and conquests of the Confederation, but was unable to join the Confederation twice (1411, 1459) because of the contradictions of the states and the envy of Bern. It was not until a few decades later that Solothurn joined the Swiss Confederation in 1481, together with Freiburg, although they were henceforth cities of second rank. More cities were added until 1513 and then together they formed the thirteen old towns . In 1530 the French ambassador also set up his seat here.

Expansion of the new canton

Medieval Solothurn initially ruled over an area that today is the municipalities of Rüttenen, Feldbrunnen-St. Niklaus, western Riedholz, Oberdorf, Langendorf, Bellach, Zuchwil, Luterbach, Biberist, Lohn, Derendingen and Messen. The Unterleberberg was added in 1362, Grenchen and Bettlach in 1389 and the Bucheggberg in 1391 . During a second expansion phase between 1402 and 1427, Thal and Gäu , together with the Basler Pfandschaft Olten, were added. The rule of Gösgen was added in 1458. With the purchase of the water authority (1466) and the conquest of Dorneck and Thierstein at the beginning of the 16th century, the canton took on its present form. The shredded outline of the state is illustrated by a popular saying:

« Little bacon and lots of rinds, lots of hag and little garden. »

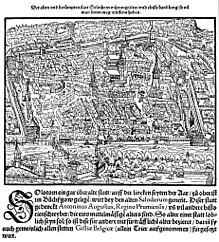

Cityscape in the 15th century

Due to the innovations in the art of war, the fortifications of Solothurn had to be expanded. In 1453, the construction of the curtain wall north of the Eichtor (Baseltor) began. In 1454 the Nydeck tower (Riedholzturm) was added, initially with a square floor plan, and in 1462 the Krummturm in the suburbs. At the end of the 1480s, the Hürlig, inner Bern and outer water gates were reinforced. Later, the Baseltor (1504 to 1508), the Burristurm (1534) and the new Riedholzturm (1548) were added on a circular floor plan. From 1467 the construction of the new town hall on Eselsgasse began, which was only fully completed in 1711 with a new double tower facade in the east. The clock tower got its astronomical clock from Winterthur Laurentius Liechti in 1545 .

When he passed through in 1418, Pope Martin V permitted the construction of the citizens' hospital and the associated Heiliggeistkapelle in the suburbs. The various figure fountains (St. Urs, Gerechtigkeit, Georg, Simeon and Mauritius), which were created during the 16th century, are decisive in the cityscape.

Image interpretation of the Stumpf Chronicle (left): The current buildings of the clock tower, town hall, Franciscan church, Baseltor, Burristurm and crooked tower are recognizable. No longer available today: the St. Ursen Minster Church, the two Bern gates, the Georgsturm in the southwest corner and the Nydeck powder tower in the northeast corner. The latter fell victim to a lightning strike with an explosion in 1546 and was immediately replaced by the Riedholzturm. The Petersturm at today's Ritterquai was also demolished in the 17th century and the Hürligturm south of the Aare in the 19th century. The three watchtowers on the northern fortress wall, however, have been preserved. There was no actual marketplace at that time, but today's Friedhofplatz is clearly recognizable. In the “Schänzli” district south of the Aare, the moat here and centuries later was flooded with Aare water, while this project north of the Aare apparently failed in part due to insufficient knowledge of physics.

Reformation and religious wars

- 1519–1533: The Reformation led to a split in faith in Solothurn; Even the Bern reformer Berchtold Haller preached at times in the Franciscan Church . During the later reformed uprising, the Solothurn mayor Niklaus Wengi the Younger prevented bloodshed. Solothurn remained Catholic. After the Reformation, the two bulky fortress towers in the west and east of the old town, the Burris and Riedholzturm , were built.

- From 1530–1792 the French embassy in Switzerland resided in Solothurn, which is why Solothurn is also called the ambassador city .

- In 1609 dark clouds of war were brewing over Europe: the alliances of the “ Protestant Union ” and the “ Catholic League ” were founded, which later fought the Thirty Years' War . It was probably no coincidence that the construction of the old armory (see under “Sights”) began in Solothurn in the same year .

science and technology

- On February 12th, 1784 the brothers Urs Jakob and Anton Tschan undertook the first Swiss unmanned hot air balloon flight from the Mutten. The flight lasted 45 minutes and there was a sheep on board with a parachute.

Time of democratization

- Around 1800 two linden trees , probably the oldest trees in the city today, were planted in front of the Capuchin Church.

- At the beginning of the 19th century, with the triumph of the liberal-democratic movement over the urban aristocracy , the previously merged institutions of the canton and municipality of Solothurn were split up. Solothurn thus became a municipality and the capital of the canton.

- Solothurn has been the seat of the Basel diocese since 1828 . The bishop resided in the Palais Besenval in the old town until the Kulturkampf

- 1819: The Savings Fund was founded as the oldest larger municipal company still in existence today in the form of the Regiobank Solothurn .

- In the wake of industrialization , Solothurn received its first rail connection in 1857, with steam trains from the Central Railway . Today's Solothurn West station building dates from that time.

- Electrification of the city began in 1895. The first transformer house at the time is still standing at St. Niklausstrasse 53.

Modern times

- The best-known and largest company ever established in Solothurn is Ascom AG. It began in 1922 as Autophon AG with around 15 employees. Today not many more people work at the Solothurn location than back then, the group has meanwhile largely left Solothurn. However, a Ypsomed branch was established at the same location , which created new jobs.

- After the First World War , the first cars appeared in the Solothurn townscape, and in 1930 the first public buses started running.

- In 1969 the first pizzeria was opened in Solothurn - a sign of the beginning integration of immigrant families.

- Until 1976 the city's rubbish was disposed of in landfills . As a result of the water pollution , the affected areas should be rehabilitated as soon as possible.

- In 1994, the heavily drug addicts received a contact point for controlled and “clean” drug consumption.

- The population grew in step with industrialization : in 1850 approx. 5,000 people, in 1900 10,100 people, today 15,400 people.

Urban development

Shortly after the liberal revolution of 1830 , Solothurn began to tear down the city walls and city fortifications from the Middle Ages and early modern times, as they - analogous to the various internal tariffs , units of measure and monetary currencies at the federal level - for the longed-for trade and industrialization - recovery were seen as a hindrance. Outside of these fortifications, there were only a few residences of the fallen aristocratic families, some farms and church institutions (e.g. monasteries, including the Capuchin monastery in Solothurn ).

In the period from 1850 to 1900, the population in the city of Solothurn doubled from around 5,000 to around 10,000 people. A watercolor by L. Wagner from 1884 shows that additional living space for the newcomers was created in advance in the Westring area up to the current central library. At that time, 10,000 people found accommodation in an area largely only in the old town and suburbs as well as the Westring district (compared to the size of the city today, for a population of around 15,500 people). At that time, the service sector was still very weak: Almost all of the space mentioned was used for residential purposes, there were hardly any offices and shops, not to mention department stores, etc. Also, the individual apartments were generally much smaller than they are today .

From 1900 to 1950, the urban population of Solothurn grew by almost 7,000 to 16,700. This was done in advance through the sustainable development of the Dilitsch, Allmendstrasse, Obere Steingruben, St. Kathrinen and Südstadt districts. The first zoning plan dates back to 1938 , which the city then created on its own and without any requirements from the federal government or the canton. However, it only contained very rudimentary requirements: apartment blocks were still allowed to be built in two-family quarters, and residential and industrial zones were not yet clearly separated from each other.

From 1950 to the present day, the population in Solothurn decreased somewhat, albeit with some fluctuations within this time window. The settlement area, on the other hand, grew steadily and significantly, due to the increasing share of single-family house construction, the ever-increasing need for individual living space, increased single-person households, expanding commercial and industrial buildings as well as the increasing demand for office and retail space. At the beginning of the 1970s, the "Brühl development plan" also tackled the development of the Weststadt in the narrower sense, with the initially controversial first high-rise buildings in the city, the Riedmatt blocks.

The Wasserstadt Solothurn project has been in the planning phase since 2006 .

The severe house fire in Solothurn in 2018 triggered a discussion about the duty of smoke detectors.

The old town today

On the occasion of a study week at the canton school in 2000, the development of Solothurn's old town , which was medieval in its floor plan and partly also in the building fabric, was examined (published by the Natural Research Society ). In 2000 there were still 1050 people living there, which corresponds to a decrease of 40% since 1971. According to the study, residential use is increasingly giving way to commercial use, with supra-regional and international chain stores increasingly forming the focus. The living space that is no longer available on the regular floors is partially offset by the expansion of attic floors. Due to the very high land prices, apartment rents have also reached a considerable level. On March 29, 2011, a fire that broke out in the attic at Hauptgasse 54 damaged five buildings in the roof area, some severely.

population

| year | Residents |

|---|---|

| 1850 | 5,000 |

| 1900 | 10,100 |

| 1950 | 16,700 |

| 2010 | 16'163 |

With 16,777 inhabitants as of December 31, 2018, Solothurn is the second largest city in the canton of Solothurn after Olten and one of the smaller cities in Switzerland. In 2009, 75,359 people lived in 24 communities in the Solothurn agglomeration , which also includes communities from the Lebern and Wasseramt districts. By 2018 the city of Solothurn wanted to merge with the four surrounding communities of Biberist , Derendingen , Luterbach and Zuchwil , which would have increased the city's population to around 42,000. Due to negative referendums, the merger did not take place.

Religions

Solothurn is traditionally Catholic . Due to the internal migration in recent centuries, however, a large Reformed community also emerged in Solothurn . The Christian Catholic community is based in the Franciscan Church (Solothurn) . Muslims and Buddhists came to the city for the first time in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s .

In 2000, 35.2% of the population was Roman Catholic (5,413 people), 29.6% was Protestant (4,551) and 5.9% (907) stated that they were Muslim. As a religious affiliation is indicated 20.2% (3'106) and 3.9% (599) did not specified.

immigration

The proportion of foreigners is 21.4 percent, which is above the cantonal average of 20 percent. The largest proportion are citizens from Italy , the former Yugoslavia , Turkey , Sri Lanka , Thailand , Germany and Spain .

politics

legislative branch

The legislative authority and supreme body of the municipality is the municipal assembly . It takes place two to four times a year in the Landhaus-Saal. It is formed from all members of the community who are entitled to vote, although usually only a small part of them visit it.

executive

The municipal council is the executive and administrative body of the municipality. It consists of 30 members and is elected by the people using proportional representation. The term of office is four years. It meets in the meeting room / council hall of the country house .

In the last election, the parties achieved the following number of seats:

| Political party | 1997 | 2001 | 2005 | 2009 | 2013 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDP | 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 8th |

| SP | 7th | 8th | 9 | 7th | 8th | 9 |

| CVP | 6th | 5 | 5 | 7th | 5 | 5 |

| Green | 3 | 3 | 4th | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| SVP | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| GLP | - | - | - | 0 | 1 | 1 |

There is also a local council commission, consisting of 7 members (3 FDP, 2 SP, 1 CVP and 1 Greens) who are elected by the local council from among its members. The city president is National Councilor Kurt Fluri ( FDP ), who is also the president of the GRK.

Judiciary

The Solothurn-Lebern judges' office is responsible for legal disputes . In addition, the cantonal higher court has its seat in the city of Solothurn.

National elections

In the 2019 Swiss parliamentary elections, the share of the vote in Solothurn was:

| SP | Green | FDP | SVP | glp | CVP | BDP | Hemp party |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24.9% | 20.6% | 19.7% | 12.3% | 9.6% | 8.8% | 1.8% | 1.1% |

coat of arms

The red and white shield was adopted from the city arms as the canton's coat of arms. It has been used by local authorities since 1394. The colors have been known since 1443.

Quarters

Solothurn is divided into 14 quarters:

- Obach

- Bruehl (Brueu)

- Segetz

- Wildbach / Weststadt / Touring

- Dilitsch

- Hermesbühl (Hermesbüeu) / Heidenhubel (Häidehubu)

- Old Town (Autstadt)

- Loreto / Graves (Graves)

- Dürrbach / Ziegelmatte (Zigumatt) / Steingrube West (Stäigruebe West)

- Steingrube Ost (Stäigruebe Ost) / Fegetz

- Hubelmatte (Hubumatt)

- Steinbrugg (Stäibrügg) / Forest / Schützenmatte (Schützematt)

- Suburb

- Beautiful green (beautiful green)

Twin cities

Heilbronn

After the First World War , there was great poverty and famine in Heilbronn . In order to take action against this misery, the pastor Anna Kopp-Sieber set up and ran the "Swiss Aid" in Heilbronn in 1924 . Through this facility, food and clothing were given out to those in need, creating the first connection between the two cities.

The merger to form twin cities came about when the mayor of Heilbronn Hans Hoffmann and the Solothurn city mayor Fritz Schneider sealed the twin city document in Heilbronn on September 19, 1981 . On May 7, 1982, this merger was confirmed again in Solothurn with the signature of the then Solothurn mayor Urs Scheidegger and Hans Hoffmann.

Krakow

Tadeusz Kościuszko was a Polish general and leader of the uprising of 1794 against the partitioning powers Russia and Prussia. After a defeat in the same year, he was captured, but was defeated by Tsar Paul I in 1796 . pardoned. He fled into exile, which brought him to the United States of America , later to Paris and finally to Solothurn. Here he continued his struggle for Polish independence in vain until he died on October 15, 1817. While his entrails (except for the heart, for which an urn was made) were buried in a cemetery in Zuchwil , the embalmed corpse was transferred from the Jesuit church in Solothurn to the royal crypt in Krakow . The city union was decided in 1990.

There are two monuments to Kościuszko in Solothurn .

Le Landeron

In 1449 the citizens of Le Landeron (NE) concluded a castle right with those of the city of Solothurn , which was confirmed several times until 1783. Although the federal government at that time went back a long way, it was not until 2003 that a town twinning was established. The community of Solothurn has always operated vineyards in Le Landeron and sells its community wine in the suburb of Solothurn.

Infrastructure

media

The most famous newspapers are the Solothurner Zeitung , the Azeiger , both of which are published by the Vogt-Schild company . In addition, the Solothurn Week is a popular Anzeiger newspaper . Radio 32 was the only radio station in town, and now another station has started operating with the radio station Radiologische.

traffic

Public transport

The main train station in Solothurn , the Westbahnhof and, since December 2013, the Allmend train station provide the train connection , with the last two only serving regional traffic. The Swiss Federal Railways (SBB) offer connections in the direction of Lausanne / Geneva or St. Gallen / Zurich and in the Bernese Jura via Moutier to Sonceboz-Sombeval . BLS AG also provides the connection to the Emmental to Burgdorf and Thun , while the Bern – Solothurn regional transport (RBS) operates the meter-gauge line to Bern . Another meter-gauge train connection is provided by the Aare Seeland mobil (ASm) between Solothurn and Niederbipp - Langenthal . This operates two more stops in the city. The Bielersee-Schifffahrts-Gesellschaft operates shipping from Solothurn via the Aare to Nidau and Biel.

The immediate vicinity can be reached through the Solothurn and Surroundings Bus Company (BSU). The first Jura chain can be reached with the PostBus route 40.012 Solothurn - Balmberg . Following the closure of the Oberdorf – Weissenstein chairlift , a post bus led to the Kurhaus on the Weissenstein mountain , initially on Wednesdays, Saturdays and Sundays , and since December 2014 a gondola lift.

Private transport

Since the completion of the A5 motorway section between Solothurn and Biel, there have been three exits (two full and one half connections) to the city of Solothurn.

Air traffic

The closest airfield is in Grenchen , which is mainly used by amateur pilots, parachutists, air taxis and other private individuals. There are no scheduled flights. The airports of Bern-Belp , EuroAirport Basel Mulhouse Freiburg and Zurich can be reached by train in 75–100 minutes.

education

There is a wide range of educational opportunities in Solothurn. All levels of compulsory elementary school are taught in seven municipal schools. There is also a special educational school, a speech therapy outpatient clinic and a music school. The Rudolf Steiner School is particularly well known among private schools .

The Solothurn Cantonal School is also located in the city . Other schools of importance are the Commercial Vocational School, the Commercial-Industrial Vocational School (GIBS), the FHNW University of Education (since 2006 part of the Northwestern Switzerland University of Applied Sciences ), the cantonal Health and Social Education Center (BZ-GS) and the adult education center .

Healthcare

Solothurn owns the Bürgerspital as the main hospital . For the city and canton, the Solothurn Citizens Hospital functions as a hospital with extended basic care. 1,200 employees work in the emergency ward, intensive care ward, all medical disciplines that are part of the fulfillment of the service mandate of a central hospital, as well as in various outpatient departments. The Bürgerspital has been completely smoke-free since 2005. It also has a blood donation center.

Until 1967, the civil parish of the city of Solothurn was the sponsor of the hospital, hence the name Bürgerspital. Since then, the Canton of Solothurn has also participated in the sponsorship. Today the modern citizens' hospital with around 300 beds serves as a central hospital for the upper part of the canton. The catchment area has around 80,000 inhabitants. The hospital has been operated by Solothurner Spitäler AG since 2006 .

There is also the Obach private clinic . All in all, there are well over 100 medical practices in the city, some of which are group practices. This above-average accumulation is explained by the central function of a main town.

Culture

Solothurn is a regional cultural center. Numerous institutions such as the city theater , the Kofmehl culture factory , the Altes Spital cultural center , the Altes Zeughaus Museum , Waldegg Castle , the Solothurn Nature Museum , the Solothurn Art Museum (Cezanne, Matisse, Renoir, Klimt, Holbein, all in individual works; Hodler, Amiet etc. .), the Blumenstein Historical Museum and the Kosciuszko Museum, which commemorates the Polish national hero Tadeusz Kościuszko , who died in Solothurn in 1817 , have a wide range of cultural activities. The city of Solothurn, together with the canton and all of the agglomeration communities, is the sponsor of the Solothurn Central Library Foundation . In Solothurn there is also the Solothurn City Orchestra.

Events

Several events take place in the city throughout the year. The best known are the Solothurn Film Festival , the Solothurn Literature Festival , the Solothurn beer days , Solothurn Classics (formerly. Classic Openair) and the carnival . At the beginning of December, the Solothurn Chlausemäret (Nikolausmarkt) takes place in the old town .

Culinary specialties

The “Solothurn Torte” is a culinary specialty of the city of Solothurn, made from ground hazelnuts, biscuit , meringue and cream. Confiserie Suter in the old town has been making this traditional specialty since 1915. The original name is: "Solothurn Cake". The biscuits are available under this name (or recently also as “Torte”) in numerous confectioneries and bakeries in the canton of Solothurn, but also from the wholesaler Coop . Another traditional specialty is Soledurner Wysüppli or Solothurn wine soup , which is prepared with bouillon and white wine .

The «Solothurn Number» 11

Solothurn has a special relationship with the number eleven , the origin of which may go back to the Middle Ages. The reason for this preference, however, is obscure. The town's citizenship was organized in eleven guilds and the first council that the people of Solothurn were allowed to provide had eleven members. After more and more such 11-way relationships appeared, the people of Solothurn began to consciously cultivate this number.

The city's landmark, St. Ursus Cathedral , has eleven altars and eleven bells. A staircase with eleven steps per section leads up to it. And the eleventh, black-painted, square floor slab in the main nave, counted from the main entrance, denotes the only place in the church from which all eleven altars or parts of them can be seen at the same time. The baroque city fortifications had eleven bastions before they were partially demolished. The city also has a “Solothurn clock” that only has eleven hours. The Foucault pendulum hanging in the Natural History Museum , which shows the earth's rotation, also rotates eleven degrees per hour relative to the earth.

A local brewery is called Öufi Bier ( Solothurn Swiss German for eleven) and produces a beer of the same name. The “Solothurn Battalion” of the Swiss Army (Infantry Battalion 11) also bears the number 11. This emerged in 2004 from Infantry Regiment 11, which was also assigned to the Canton of Solothurn.

There are many myths about the verifiable 11 relationships: Solothurn is not the eleventh canton of the Old Confederation , but the tenth. There were and are far more than eleven fountains and eleven churches and chapels in the city area. The medieval city fortifications once had more than eleven towers, but there were never more than seven city gates.

Carnival

The Solothurn Carnival does not begin on November 11th as elsewhere. ( Martin's Day ), but always on January 13th, Hilari Day . From this day on, Solothurn is called “ Honolulu ” and Rathausgasse is called “Eselsgasse”. Carnival week itself is the last week before Lent and is organized by the Honolulu Fools' Guild . The start is on « Dirty Thursday ». In the morning at 5 am, the starting signal for the « Chesslete » is given on Friedhofplatz and the old town is filled with the sounds of all kinds of noise tools. The tenue is a white nightgown, white pointed cap and a red scarf. Other highlights are the children's parade and two other carnival parades on the following Sunday and Tuesday. The Solothurn Carnival ends with the tattoo . Two blocks are created here. Each block is led by tambours from the Tamboureverein Solothurn and accompanied by «Guggenmusiken», while «I ma nüm» (I can no longer) is sung and thousands of carnival folk hop around the city in a long train. The carnival hustle and bustle is then finally ended with the traditional burning of the « Böögg » on Ash Wednesday.

"Être chargé pour Soleure"

This French saying ( "loaded for Solothurn"), which in the Romandie is widespread and a state of strong intoxication describes has its origins in the fact that Solothurn in the old Confederation residence of the French ambassador was ( "City of Ambassadors"). This led to a high consumption of wine , which is mainly from the vineyards of Lavaux was obtained. The transport took place by water over the Canal d'Entreroches . The skippers often grabbed their cargo during the voyage and therefore arrived drunk in Solothurn (where they unloaded their cargo at the former and from 1722 today's country house ).

Cooperative culture

The oldest self-managed pub in Switzerland, the Kreuz cooperative , has been located in Solothurn since 1973 . Other cooperative-oriented businesses also shape the city's flair in a special way. So z. For example, regional artists came together in the 1970s and the Künstlerhaus S11 was founded in the form of a sponsoring association, with a gallery and other joint activities. The Hotel-Restaurant Baseltor is also organized as a cooperative.

Attractions

One of the sights of Solothurn is the picturesque old town with its guild houses and figure fountains, in particular:

- The clock tower , built partly in the first half of the 12th century, is the oldest building in the city. The tower clock was made by Laurentius Liechti around 1545. Next to and under the roofed clock are colored figures with the character of a dance of death , which move with the clock, namely knight, king and death. Knight and king are dressed in the colors of the Solothurn coat of arms; the fletching of the death arrow is also in red and silver.

- The Bieltor with the Buristurm and the Baseltor with the Riedholzschanze and the Riedholzturm , which together with the Krummturmschanze testify to the former massive fortress.

- The town hall , starting with a core part from the 13th century, was constantly expanded and rebuilt into the 19th century.

- The Cathedral of St. Ursus , a 1,773 consummate Baroque-Classicist building.

- The baroque Jesuit church (built 1680–1689)

- The late medieval Franciscan Church (built 1426 to 1436)

- The St. Peter's Chapel

- The Marienkirche in Allmendstrasse

- A remnant part of the medieval fortress wall on the north side of Riedholzplatz. The other partial fortifications (entrenchments) are newer, from the 17th century. At Löwengasse there is also a stately remnant of the wall of the Roman castrum, which was built around 1700 years ago, and which encompassed an area significantly smaller than today's medieval old town.

- The 1363 first documented Schmiedsgasse, where iron was forged and the Nictumgasse, the territory of the former St. Ursen- canons .

- The country house, partly built in 1722

- In the almost traffic-free suburb, the old hospital and the Krummturm

- Various fountains, including the Schmiedengassbrunnen and the Gerbergassbrunnen .

Museums :

- The Altes Zeughaus Museum (built 1609–1614) with the largest collection of harnesses in Europe.

- The Solothurn Art Museum

- The Blumenstein Historical Museum

- The Solothurn Nature Museum

- The ENTER computer museum

- The cabinet for sentimental trivial literature (www.trivialliteratur.ch)

In 1980 the city was awarded the Wakker Prize for Swiss Homeland Security .

There are numerous church buildings in the city. Probably the most important and best known is the Roman Catholic St. Ursus Cathedral, which was completed in 1773. The diocese of Basel has had its seat here since 1828. The city is also the Roman Catholic center of the western Swiss cantons of Solothurn, Bern, Jura, both Basel, Aargau, Lucerne and Zug. Other Christian buildings are the churches of the Reformed Congregation , the Christian Catholic Congregation ( Franciscan Church ), the Methodist Church , the Salvation Army , the Vineyard Community and the Movement Plus Community. The Fatih Mosque of the Islamic Faith Community is another religious building and is located south of the main train station. Until 1983 there was also a prayer room for the Jewish religious community in the northern old town of Solothurn.

The Verena Gorge with the hermitage and Waldegg Castle are in the immediate vicinity .

Sports

The city of Solothurn offers a variety of excursions and sports. You can explore the Planet Trail on the Weissenstein local mountain or travel the Aare on an Aare ship operated by the Bielerseeschiffahrtsgesellschaft. Several major sporting events take place in Solothurn every year. B. Aare swimming and the swisswalking event. In Solothurn there is also the football club FC Solothurn and a rugby club (Rugby Club Solothurn), which plays in the National League C of the Swiss Rugby Association.

Personalities

To 1900

- Ursus († around 303), patron saint of the city

- Urs Graf the Elder (1485 / 90–1529), engraver

- Gregorius Sickinger (1558–1631), artist

- Georg Gotthart († 1619), iron merchant, guild master and poet (author of three plays)

- Johann König (1639–1691), organ builder

- Johann Wolfgang Frölicher (1652–1700) architect and sculptor

- Johann Rudolf Byss (1660–1738), painter

- Georg Gsell (1673–1740), painter

- Gaetano Matteo Pisoni (1713–1782), architect

- Franz Jakob Hermann (1717–1786), clergyman, librarian and local researcher

- Paolo Pisoni (born November 7, 1738 in Ascona ; † November 7, 1804 in Solothurn), architect in Solothurn, Kriegstetten and Basel

- Tadeusz Kościuszko (1746-1817), Polish national hero; lived in exile in Solothurn

- Viktor Franz Anton Glutz-Rüchti (1747–1824), auxiliary bishop

- Karl Ambros Glutz-Rüchti (1748–1825), abbot in the St. Urban monastery

- Augustin Keller (1754 – after 1799), one of the commanders-in-chief of the army of the Helvetic Republic

- Friedrich Pfluger (1772–1848), Dept.

- Alois Vock (1785–1857), dean of the cathedral diocese of Basel, educator and historian

- Robert Glutz von Blotzheim (1786-1818), writer

- Konrad Josef Glutz von Blotzheim (1789–1857), clergyman

- Charles Sealsfield (1793–1864), Austrian-American writer

- Karl Arnold-Obrist (1796–1862), Bishop of Basel

- Théodore Fix (1800–1846), political economist

- Johann Friedrich Dietler (1804–1874), painter and draftsman

- Joseph Anton Dollmayr (1804–1840), professor at the cantonal school

- Franz Krutter (1807–1873), writer, lawyer and politician

- Anna Martignoni (1820–1873), painter

- Wilhelm Vigier (1823–1886), liberal politician

- Otto Frölicher (1840–1890), painter

- Conradin Zschokke (1842–1918), civil engineer

- Ernst von Sury (1850–1895), neurologist and forensic doctor

- Eugen Dietschi-Kunz (1861–1951), printer and castle explorer

- Max Leu (1862–1899), sculptor

- Oscar Miller (1862–1934) art collector and patron, director of the Biberist paper mill

- Friedrich Schwendimann (1867–1947), provost of St. Ursus Cathedral and church historian

- Cuno Amiet (1868–1961), painter and sculptor

- Alfred Rudolf (1877–1955), lawyer and politician

- Gertrud Dübi-Müller (1888–1980), photographer, art collector and patron

- Albert Talhoff (1888–1956), writer and choreographer

- Richard Flury (1896–1967), composer and conductor

From 1901

- Walter Peter (1902–1997), sculptor and draftsman

- Max Brunner (1910–2007), glass painter

- Irma Tschudi-Steiner (1912-2003), pharmacist

- William A. de Vigier (1912–2003), entrepreneur

- Ruedi Walter (1916–1990), popular actor

- Agnes Gutter (1917–1982), fairy tale, children's and youth literature researcher

- Max Kohler (1919–2001), painter and graphic artist

- Elisabeth Pfluger (1919–2018), writer

- Franz Füeg (1921–2019), architect and numismatist

- Hans-Erich Keller (1922–1999), Romanist, Medievalist and university professor

- Fritz Haller (1924–2012), architect, designer

- Max Egger-Schnyder (1927–2019), politician, lawyer and writer

- Hans Oskar Kaufmann (1928–2014), archivist

- Herbert Meier (1928–2018), writer

- Otto F. Walter (1928–1994), writer and publisher

- Urs Jaeggi (* 1931), sociologist, writer and artist

- René Quellet (1931–2017), pantomime artist

- Fritz Glauser (1932–2015), archivist

- Gerhard Berger (* 1933), painter and graphic artist

- Schang Hutter (* 1934), sculptor

- Peter Bichsel (* 1935), writer

- Hugo Jaeggi (1936–2018), photographer

- Urs Joseph Flury (* 1941), musician, composer and conductor

- Martin Kohli (* 1942), sociologist

- Walter Bloch (* 1943), philologist, philosopher and writer

- Walter Schenker (1943–2018), writer

- Alfred Kölz (1944–2003), lawyer and university professor

- Hansruedi Jordi (* 1945), jazz musician

- Urs Peter Keller (* 1945), artist manager and music producer

- Anton Mosimann (* 1947), cook

- Aldo Solari (* 1947), painter, sculptor, installer

- Chris von Rohr (* 1951), rock musician

- Kurt W. Zimmermann (* 1951), journalist and publicist

- Ben Jeger (* 1953), musician and composer

- Alexander Frei (* 1954), Swiss entrepreneur and racing car driver

- Urs Frey (* 1954), documentary filmmaker

- Kurt Fluri (* 1955), politician (FDP), city president of Solothurn

- Jürg Dick (* 1963), curling player

- Barbara Wyss Flück (* 1963), councilor and canton councilor (Greens)

- Franco Supino (* 1965), writer

- Rosanna Rocci (* 1968), Italian pop singer

- Alexander Popov (* 1971), Russian swimmer; has lived in Solothurn since 2003

- Marc Schütrumpf (* 1972), director

- Martin Oeggerli (* 1974), scientist and science photographer

- Seppi Käppeli (* 1976), jazz musician

- Pascal Bader (* 1982), football player

- Christof Schauwecker (* 1986), City Council and Cantonal Council (Greens)

- Daniela Ryf (* 1987), triathlete

See also

literature

- Claudio Affolter: Solothurn: Architecture and Urban Development 1850–1920 . [Solothurn]: Lehrmittelverlag Kanton Solothurn, 2003, ISBN 3-905470-18-7 .

- Urs Amacher: Holy Bodies. The eleven catacomb saints of the Canton of Solothurn. Knapp Verlag Olten, 2016, ISBN 978-3-906311-29-6 .

- Bruno Amiet : History of Solothurn . Volume I. City and Canton of Solothurn from Prehistory to the End of the Middle Ages. Vogt-Schild AG, Solothurn 1952.

- Ylva Backman: Graves near St. Peter and St. Urs in Solothurn - from Roman times to the Middle Ages . In: Archeology and Monument Preservation in the Canton of Solothurn . Issue 16, pp. 61-70. Solothurn 2011, ISBN 978-3-9523216-6-9 .

- Stefan Blank, Markus Hochstrasser: The City of Solothurn II . Die Kunstdenkmäler des Kanton Solothurn, Volume II. Ed. By the Society for Swiss Art History GSK, Bern 2008 (Kunstdenkmäler der Schweiz Volume 113), ISBN 978-3-906131-88-7 .

- Julius Derendinger: History of the Canton of Solothurn from 1830–1841 . In: Basler Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Altertumskunde , Vol. 18, 1919, pp. 255-418 ( digitized version ).

- Felix C. Furrer (ed.): Solothurn: image of a city . Solothurn: Vogt-Schild, 1996. ISBN 3-85962-1069 .

- Rolf Max Kully: Solothurn place names. The names of the cantons, districts and municipalities . Solothurn name book 1. Printed matter management / teaching material publisher Canton Solothurn, 2003, ISBN 3-905470-17-9 .

- Andrea Nold: A quarter on the Aare in Solothurn, Rome . In: Archeology and Monument Preservation in the Canton of Solothurn . Issue 16, pp. 47-60. Solothurn 2011, ISBN 978-3-9523216-6-9 .

- Samuel Rutishauser: The city of Solothurn. (Swiss Art Guide, No. 912/913, series 93). Ed. Society for Swiss Art History GSK. Bern 2013, ISBN 978-3-03797-111-6 .

- Urs Scheidegger: It wasn't always like this ... - Leafed through the files of the city councilors of Solothurn . Volume I. Vogt-Schild Verlag, Solothurn 1985, ISBN 3-85962-073-8 .

- Urs Scheidegger: It wasn't always like this ... - Leafed through the files of the city councilors of Solothurn . Volume II. Vogt-Schild Verlag, Solothurn 1986, ISBN 3-85962-083-5 .

- Benno Schubiger: The city of Solothurn I . The Art Monuments of the Canton of Solothurn, Volume I. Ed. By the Society for Swiss Art History GSK. Wiese Verlag, Basel 1994, (Art Monuments of Switzerland, Volume 86), ISBN 3-909164-08-0 .

- Solothurn - Contributions to the development of the city in the Middle Ages . Colloquium from 13./14. November 1987 in Solothurn. Publications of the Institute for the Preservation of Monuments at the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich, Volume 9, Verlag der Fachvereine, Zürich 1990, ISBN 3-7281-1613-0 .

- City history of Solothurn, 19th and 20th centuries . Edited by the community of the city of Solothurn. Lehrmittelverlag des Kantons Solothurn, Solothurn 2020, ISBN 978-3-905470-81-9 .

- Stuart Morgan: Vauban's project to fortify a Swiss city. In: Cartographica Helvetica Heft 1 (1990) pp. 22–28 full text [concerns the city of Solothurn].

- Thomas Wallner: Solothurn - a beautiful story !: from the city to the canton. 3rd revised edition. [Solothurn]: State Chancellery of the Canton of Solothurn, 1993.

- Erich Weber (Ed.): Across the River - The Solothurn Aare Bridges . Series of publications Historisches Museum Blumenstein, No. 2. Solothurn, 2008.

Web links

- Website of the city of Solothurn

- Region Solothurn Tourism Accessed May 4, 2015

- Pierre Harb, Hans Braun, Erich Meyer, Erich Weber, Peter Michael Keller: Solothurn (community). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Burgenwelt: Solothurn city fortifications

Individual evidence

- ↑ Permanent and non-permanent resident population by year, canton, district, municipality, population type and gender (permanent resident population). In: bfs. admin.ch . Federal Statistical Office (FSO), August 31, 2019, accessed on December 22, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Lexicon of Swiss municipality names . Edited by the Center de Dialectologie at the University of Neuchâtel under the direction of Andres Kristol. Frauenfeld / Lausanne 2005, p. 839 f.

- ↑ Schubiger 1994: p. 51

- ↑ Solothurn 1990: pp. 12-13

- ↑ Solothurn 1990: p. 13

- ↑ Schubiger 1994: pp. 16-17

- ↑ a b Schubiger 1994: p. 52

- ↑ Nold 2011: p. 48

- ↑ Weber 2008: pp. 11-19

- ↑ Kully 2003: pp. 623-625

- ↑ Solothurn 1990: pp. 15-17 and Backman 2011: p. 68

- ↑ Solothurn 1990: pp. 13-14

- ↑ Schubiger 1994: p. 3

- ↑ Solothurn 1990: pp. 20-21

- ^ Matzke, Schweizer Münzblätter 241, March 2011

- ↑ Walter Herzog: The Gurzelngasse in Solothurn . In: Yearbook for Solothurn History . tape 41 , 1968, p. 353-366 , doi : 10.5169 / seals-324387 .

- ^ Stadtmist, Solothurn: The household garbage dumps of the city of Solothurn. In: Federal Office for the Environment . Retrieved March 24, 2020 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Wagmann: A conflagration that could hardly be stopped . In: Solothurner Zeitung . March 29, 2011. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ↑ permanent resident population. Taking into account the non-permanent resident population, Solothurn is in third place, behind Olten and Grenchen . Solothurn is growing - Grenchen is within reach. Solothurner Zeitung , February 5, 2013, accessed on June 11, 2013 .

- ↑ Urban population: agglomerations and isolated cities ( Memento from 23 September 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (analysis by the Federal Statistical Office)

- ↑ Five parishes are working out a merger proposal. Retrieved February 8, 2013 .

- ↑ Elections and Votes. Retrieved August 5, 2020 .

- ^ Federal Statistical Office : NR - Results parties (municipalities) (INT1). In: Federal Elections 2019 | opendata.swiss. August 8, 2019, accessed August 1, 2020 .

- ↑ Solothurn's coat of arms on the Heraldry of the world website, accessed January 28, 2015

- ↑ Hans Sigrist: From the Solothurn legal and cultural history. Chapter: Coat of arms and seal of the Solothurn estate . In: Yearbook for Solothurn History . tape 52 , 1979, pp. 197-207 , doi : 10.5169 / seals-324709 .

- ↑ Official homepage of the municipality of Zuchwil: Thaddäus Kosciuszko, 1746–1817 ( Memento of the original from January 19, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ SRF: Two new train stations for the Solothurn region inaugurated

- ^ Website of the Solothurn City Orchestra

- ↑ Magical Chlaus Maret in Solothurn . Association per cemetery space. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ↑ "Inventor of the Original Solothurner Torte®" , Land of Inventors, The Swiss Magazine for Innovations, 2010

- ↑ Soledurner Wysüppli . myswitzerland.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved on August 1, 2012.

- ↑ Amiet 1952: pp. 352-362

- ↑ Solothurn 1990: pp. 265-286

- ↑ Hans Georg Wehrens: The dance of death in the Alemannic language area. "I have to do it - and don't know what" . Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg 2012, p. 153, ISBN 978-3-7954-2563-0 .

- ^ Rudolf Walz: St. Peterskapelle in Solothurn. (Swiss Art Guide, No. 179). Ed. Society for Swiss Art History GSK. Bern 1975, ISBN 978-3-85782-179-0 .

- ^ Fabrizio Brentini: Marienkirche in Solothurn. (Swiss Art Guide, No. 750, Series 75). Ed. Society for Swiss Art History GSK. Bern 2004, ISBN 978-3-85782-750-1 .

- ^ Hans-Rudolf Heyer: Paolo Pisoni. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . February 3, 2010 , accessed February 17, 2020 .

- ↑ Martignoni, Anna. In: Sikart (status: 2011), accessed on March 21, 2017.