History of the Grand Prix before 1950

The history of the Automobile Grand Prix did not just begin with the introduction of the Automobile World Championship , which was held according to the rules of Formula 1 , in 1950 , but much earlier. As early as the mid-1890s, the Automobile Club de France (ACF), founded in 1895 as the first automobile club in the world, organized a “big” race once a year, which was the highlight of the season. These were still so-called "city-to-city" races on public country roads, in which the participants were sent out one by one at time intervals. These events were subsequently declared Grands Prix by the ACF .

With the races for the Gordon Bennett Cup , which are also held annually, there was also a first attempt to hold a kind of automobile world championship from 1900 to 1905 . In view of constantly increasing speeds, the ACF issued technical regulations in the form of a so-called racing formula for the first time in 1902 , which the participating cars had to comply with. Nevertheless, the frequency of accidents continued to increase so that from 1903 only circuit races could be carried out on closed courses. In that year, fixed national colors were also introduced, which were essentially retained in motorsport until the sponsorship was approved at the end of the 1960s.

As the successor to the Gordon Bennett Races, the main race organized by the ACF ran for the first time in 1906 under the name Grand Prix (in German: "Großer Preis"). The first Grand Prix winner in history was the Hungarian-born driver Ferenc Szisz in a Renault . In retrospect, however, the ACF also retrospectively awarded the city-to-city races held between 1895 and 1903 the designation Grand Prix , which is why the race from 1906 to this day is still officially known as “9. Grand Prix de l'ACF ”.

After attempts had initially been made to establish counter-concepts to the Grand Prix with the Targa Florio in Italy and the Kaiserpreis race in Germany , in the 1920s the automobile clubs of other countries gradually began to organize Grand Prix races. so that the name of the country was added to distinguish it (e.g. “Gran Premio d'Italia”, “Grand Prix of Germany” etc.). The 1922 Italian Grand Prix was also the first Grand Prix to be held on a purpose-built permanent circuit, the Autodromo di Monza . In order for the automobile manufacturers to be able to take part in all of these races, it was also necessary to pass the technical and sporting regulations that had previously been independently laid down by the ACF for its races in the form of the respective Grand Prix formula through the International Automobile Association (at that time still under the Designation AIACR) now to be regulated across countries. For this purpose, the Sports Commission (CSI) was set up in 1922 , from which the International Grand Prix formulas were subsequently adopted, from which Formula 1 ultimately emerged. Further milestones in the development were the introduction of mass starts in 1922 , in which the cars were sent into the race simultaneously from a common rolling or standing starting formation , the increasing use of supercharged engines from 1923 and the approval of single-seat racing cars (so-called monopostos in 1927 ), after a mechanic had previously been mandatory on board the racing cars in addition to the drivers.

In the mid-1920s, the idea of a world championship was also taken up again, for which the results of the international Grand Prix races of one year were added together. As with the Grand Prix races themselves, this was a pure competition between the automobile manufacturers, but there was no driver classification. The first world champion was Alfa Romeo in 1925 , followed by Bugatti in 1926 and Delage in 1927 . At the end of the 1920s, however, the Grand Prix sport fell into a crisis because, in view of the enormous increase in technical complexity and finally also under the impact of the global economic crisis, hardly any manufacturer could afford to develop special Grand Prix racing cars based on the given racing formula . Instead, a heyday of so - called formula - free races began , in which the numerous private drivers who were represented provided impressive starting fields that were interesting for the spectators. The participants financed themselves mainly through inaugural bonuses negotiated with the organizers (so-called “ entry fees ”), the amount of which usually depends on the attractiveness of the respective audience. The CSI finally bowed to this development and from 1931 largely dispensed with any technical specifications in its official racing formula, so that the Grand Prix participants could now compete with practically any type of racing car that was accepted by the respective organizer. Another development towards greater proximity to the people was the increasing spread of races on street circuits . The first such event was the Monaco Grand Prix in 1929 , which was raised to the rank of Grande Épreuve from 1933 (the distinction had become necessary due to the inflationary use of the term Grand Prix even for less important races).

However, the technical development soon afterwards again led to such a rapid increase in mileage that the CSI was again forced to react through technical restrictions in 1934 . By setting an upper weight limit, engines that are too large and powerful should be prevented. This so-called "750 kg formula" benefited above all the two German automobile companies that had just entered Grand Prix racing, Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union , which, in view of their technical and financial possibilities and not least with support from the Nazi Regime in terms of lightweight construction and chassis technology were able to achieve a technological lead. Grand Prix racing in the second half of the 1930s was characterized by the complete dominance of the German Silver Arrows , while at the same time automobile racing in the other traditional motorsport nations was increasingly being pushed into other racing categories. In France, for example, interest turned primarily to sports car races with large-volume naturally aspirated engines up to 4.5 liters, while in Great Britain and finally also in Italy the so-called Voiturette class with turbocharged engines up to 1.5 liters became more popular from year to year .

After the end of the Second World War , automobile sport had to be completely reorganized with the loss of the German Grand Prix racing teams. For this purpose, the International Grand Prix Formula adopted for 1947 was heavily geared towards the available vehicles. The result was essentially a combination of the Italian and British Voiturettes with French sports cars converted into makeshift racing cars, in which Alfa Romeo soon dominated the action. At the same time, a second Grand Prix formula was officially introduced for the first time in 1948 as the successor to the previous Voiturette class, which had been upgraded in this way, and the organizers of races below the Grandes Épreuves could now opt for it. In order to be able to differentiate between the two formulas by name, designations such as “Formula A” and “Formula B” were used at the beginning until the terms Formula 1 and Formula 2 gradually became established in common parlance .

For 1950 , the international automobile umbrella organization , which has meanwhile been renamed FIA , finally announced the renewed introduction of an automobile world championship (see history of the automobile world championship ).

Origins (1867-1894)

The first documented races for vehicles without wind or muscle power drive from around the second half of the 19th century were about performance comparisons between self-propelled steam tractors , the main aim of which was to demonstrate the usefulness of such machines. Only with the appearance of the first vehicles designed for individual transport towards the end of the 19th century did the sporting aspect become increasingly important, with the early events closely related to cycling, which was also quite young. In any case, "automobiles" were initially only viewed as another type of "horseless vehicle" and it was initially not foreseeable which drive concept would ultimately prevail.

For example, in 1894 for the trip from Paris to Rouen , which is generally regarded as the first major competition in motor sport history, in addition to automobiles equipped with internal combustion engines, according to today's conception, two- and three-wheelers, as well as vehicles with steam, electric or even spring or Muscle power drive registered. Although this event was not yet a "race" in the modern sense of the word, because it was not the speed achieved alone that was decisive for the award of the winner's prize, but above all criteria such as ease of use and economic efficiency in operation Distance, Count Albert de Dion on his steam wagon , received the greatest public attention among the participants.

The Era of the Great City-to-City Races (1895-1903)

This set the course and in 1895 the first “real” automobile race took place with the race from Paris to Bordeaux and back , in which the aim was to cover a given distance in the shortest possible time. The fastest over the distance was Émile Levassor on Panhard-Levassor , whose car, however, did not comply with the regulations. Paul Koechlin on a Peugeot was therefore declared the first official racing winner in the history of motor racing . In the same year, the Automobile Club de France (ACF), the first automobile club in the world, was founded, whose primary objective was to organize further such racing events every year from now on. Also in 1895, the Chicago Times-Herald Contest was the first major car race in the USA. The winner under adverse conditions was James Frank Duryea , who thus established the history of American motor racing.

These first major automobile races were held on public roads, with the participants being sent out individually and at predetermined intervals. The distances to be covered were enormous, and there were no paved roads or any barriers or any other safety precautions. Internal combustion engines had already become generally accepted as the only drive source usable for racing events, but from a modern point of view, the cars were still primitive and very prone to defects, required constant lubrication and technical care in operation, and tire damage or broken wheels were practically the order of the day for the participants. In order to repair the damage and to be able to maintain the journey at all, there was always another mechanic on board in addition to the driver. And although the through-town passages were usually "neutralized" (ie not timed), as the speed increased, people on the lane and in particular the risk of collision with animals moving around became an almost constant threat, especially since the development of chassis technology and brakes clearly lagged behind those of Year on year the engine performance rose sharply. In 1895, the first race from Paris to Bordeaux and back was completed with an average of less than 25 km / h, whereas in 1903 the fastest participants achieved over 100 in the last big city-to-city race from Paris to Madrid on the same route section km / h is more than four times the average speed. With engine sizes of regularly around 15 liters displacement, performance values of around 100 hp have already been achieved. Even the interim introduction of a first racing formula, with which the curb weight of the car was limited to 1000 kg (plus 7 kg extra for vehicles with magneto ignition) from 1902 onwards , had not been able to slow down this development in the long term, which was mainly due to the increasing spread of engines controlled valves played a decisive role. Instead - often with a very generous interpretation of the term "empty" - all possibilities of weight saving were used by reducing the car to its absolutely necessary components at least during vehicle acceptance, often without any form-giving body, passenger seat or other similarly "superfluous" Facilities. In parallel to the ongoing increase in performance, there was also a general change in the design principles. While in the early races the vehicles were still largely reminiscent of motorized horse-drawn carriages, by the turn of the century the long-term “modern” form of the automobile with front-engine and rear-wheel drive had already established itself.

Almost as quickly as the technical development, the change in automobile sport from the curious public spectacle and pastime of technology-loving members of the upper class to a tough competition among automobile manufacturers for success and market shares took place. Race victories were synonymous with brand prestige and successful cars could often be sold directly on site to exclusive customers, sometimes even at a multiple of the actual list price. As a result, in addition to the development of increasingly sophisticated racing cars designed solely for competitive use, the participating automobile companies also made increasing use of contractually bound professional racing drivers. In this way, a certain long-standing gap soon developed between the so-called “amateur” or “ gentlemen's drivers ” and the “works” or “factory drivers” , who are often former racing cyclists or personnel recruited from mechanics acted. This even went so far that individual events were expressly reserved for one or the other group of participants.

All in all, motorsport also experienced increasing spread internationally. The ACF, founded in 1895, was followed in 1896 by the Belgian, 1897 by the British and in 1898 by the automobile clubs of Austria, Italy and Switzerland, and from 1898 onwards , the annual Grand Race organized by the ACF also regularly connected European capitals. Also in the German Reich in 1899 the efforts, which at first diverged in the individual states, were so oriented that a common umbrella organization could be founded with the "German Automobile Club" (DAC; today AvD ). Nevertheless, the ACF remained practically the only one to set the tone when it came to organizing important - and at least rudimentary "international" - races.

In view of the impossibility of adequately cordoning off the stages that stretched over hundreds of kilometers, there was considerable resistance from the beginning, especially among the rural population, to the implementation of automobile races. With the increase in speed, the number of incidents increased to the same extent, often with fatal results, so that after such incidents there were increased difficulties in the approval of such events. After all, the tragic course of the "death race" from Paris to Madrid in 1903, which had to be prematurely stopped after eight deaths on the way, also meant the end of the era of great city-to-city motor racing.

→ Seasonal reports: 1895 , 1896 , 1897 , 1898 , 1899 , 1900 , 1901 , 1902 , 1903

Trailblazer for the Grand Prix : The Gordon Bennett Cup and the first circuit races (1900–1905)

The idea for the first international automobile competition in history stems from an unsuccessful challenge to the winner of the Paris – Bordeaux 1899 race, Fernand Charron , by the American racing driver Alexander Winton . Until then, all races had been national events in principle, in which at most a few foreign guest starters had participated. James Gordon Bennett , the publisher of the New York Herald newspaper , took up the idea of a competition between the automobile nations and donated a challenge prize for 1900 with the Coupe Internationale , for which the name Gordon Bennett Cup soon became common. The regulations provided for a race to be held once a year, with the victorious automobile club then having the right to organize events for the following year. A certain minimum distance was stipulated for the races and a maximum of three cars per nation were allowed to compete, all of which had to be manufactured in the respective country.

The first editions of the Gordon Bennett Cup turned out to be a farce. The superiority of the French cars was overwhelming and the response abroad was little or no response, especially since smaller countries in particular had major problems with completely producing racing cars at all. H. including all accessories such as tires and ignition - to be manufactured in your own country. At the first event in 1900 with representatives from Belgium and the United States, at least according to paper, there was still international participation, in 1901, for example, the French team was even completely among themselves. A chance arose for the sparsely represented foreign competition if the cars from France were canceled, as in 1902 , when the trophy went to a foreign club for the first time after the victory of the British Selwyn Edge on Napier . Instead of a real “race”, in these first editions of the Gordon Bennett Cup , given the small fields of participants and the high dropout rate at the same time, it was primarily just a matter of overcoming the distance somehow in order to achieve success. Attractive independent competitions that justified the organizational effort could not be achieved in this way. If the first edition in 1900 was at least an independent event - albeit largely unnoticed by the public - the Coupe Internationale was wisely recognized by the ACF in the following years in the form of special ratings in other important races ( Paris-Bordeaux 1901 and Paris- Vienna 1902 ), whereby the winners of the Gordon Bennett Cup did not reach a position in the middle of the overall ranking.

Of all things , the last of the great city-to-city races from Paris to Madrid in the spring of 1903, which went down in history as the death race, made a decisive contribution to an unlikely upswing in the Gordon Bennett Cup. After this catastrophe, a general ban on all speed competitions on public roads that were not cordoned off put an abrupt end to the previous format, but the solution that saved the day was to switch to the new type of circuit racing .

Even in the early years of motorsport there were competitions on horse races or other stadium-like facilities, but this form of "oval race" prevailed above all in the United States. In Europe, such events were seen as undemanding spectacle for the public, only races on "real" roads over corresponding distances were viewed as true sport. The right way out was found in 1902 when, at the instigation of the Belgian racing driver Baron Pierre de Crawhez, a really important race was held for the first time on a demanding road circuit on the 85.4 km long Circuit des Ardennes (Ardennes circuit ) near Bastogne, which was a total of six times . In contrast to the classic city-to-city races over hundreds of kilometers, this offered the opportunity to temporarily block the race track from general traffic and at least to secure it in basic features with a manageable number of stewards and marshals, without any major losses having to accept the total distance. For the spectators, this also had the advantage that they could now see the participants in the race several times and thus better follow the action.

After the British Automobile Club had decided inevitably for a road circuit near the Irish city of Athy for the 1903 Gordon Bennett Race to be organized by it, due to the lack of a suitable cross-country route , the event remained the only major motor sport event of the year after the "city races" were banned left. The participation was accordingly, and with teams from Great Britain, France, Germany and the USA, the Gordon Bennett Cup really lived up to its claim as an international competition for the first time. From now on, the Gordon Bennett Races represented the absolute highlight of the season, accompanied by a correspondingly large media presence. There was no longer any shortage of car manufacturers willing to take part, and with the participation of all the major automobile nations, motorsport was increasingly caught in the widespread national fever. In the public perception, racing victories were equated with national prestige, especially since the racing cars now also had to be painted in dedicated national colors, which were essentially retained until the sponsorship was approved at the end of the 1960s. Especially between France and Germany, whose team won the Gordon Bennett trophy at the first attempt in 1903 with the victorious Mercedes racing car of Belgian Camille Jenatzy , a particularly pronounced rivalry developed in the period that followed, which was not least fueled by that the German imperial family made the race, which was held in Germany in the following year, a national matter through its official presence and participation.

From France in particular, however, there was now increasing criticism of the competition mode, although Léon Théry with Richard-Brasier was last able to beat the German Mercedes racing cars both times in 1904 and 1905 . In the meantime, however, up to ten French automobile manufacturers were pushing for their participation, so that separate national elimination races had to be held there to determine the three representatives for the official international competition. There were up to thirty participants at the start, so that the competition in the French preliminary rounds was sometimes even tougher than in the actual Gordon Bennett races. It was felt all the more unfair that, in stark contrast to this, Mercedes, taking advantage of a loophole in the regulations, was able to compete with up to six cars in the Cup, i.e. twice as many as the entire French automotive industry put together. The "trick" was to declare three of the cars as vehicles from German production and three from the Austrian branch ( Austro-Daimler ). Although the trophy was subsequently won twice by French cars (in 1904 on German soil), this ultimately led to the ACF defending the Cup in 1906 no longer being willing to host another race for the Coupe Internationale . He replaced the Grand Prix de l'ACF , in which the French automobile club was now again sole director and could decide on the conditions of participation.

→ Seasonal reports: 1900 , 1901 , 1902 , 1903 , 1904 , 1905

Birth of the Grand Prix -race (1906-1911)

Due to the reservations about the existing regulations, the demand arose from the ranks of the French automobile industry as early as 1904 to combine the French elimination race with the Coupe Internationale (in the form of a special ranking). The new big race that emerged in this way was to run under the title Grand Prix de l'Automobile Club de France and give all manufacturers equal opportunities to participate, regardless of their national origin. The ACF took up this idea willingly, but wanted to continue to allocate different contingents of participants to the individual countries according to the “importance” of the respective automotive industry. Naturally, this proposal met with the resistance of the other nations, so that at a congress of the recently founded International Automobile Association AIACR ( Association Internationale des Automobile Clubs Reconnus ) in early 1905 the compromise was reached, the Gordon Bennett Cup and the Grand Prix in to run in two separate races this year. However, this again met with strong rejection of the French automobile companies, who wanted to see “their” Grand Prix as a kind of world championship in the form of a stand-alone season highlight. The result was that the ACF postponed the hosting of the Grand Prix to 1906, but at the same time announced that it would no longer hold a race for this competition if France won the Gordon Bennett Cup in 1905.

So finally in 1906 with the race for the Grand Prix de l'ACF the first official Grand Prix in automobile history was organized. Regardless of the country of origin, up to three racing cars per automobile manufacturer were admitted, as was originally requested by the representatives of the French industry. In accordance with its rank as the most important of all competitions, the race was held over a track length of over 1200 km and on two consecutive days. For the first time, a parc fermé was set up because, according to the regulations, it was not allowed to work on the cars between the two runs. The most important technical innovation was the introduction of removable rims with pre-assembled tires, which enabled the participants equipped with them to achieve a decisive time advantage for the extremely frequent tire damage.

Otherwise a certain uniformity had developed in the racing cars. With a few exceptions, the cars were equipped with four-cylinder cylinders, each with a cylinder capacity of between 12 and 18 liters cast in pairs, with some aimed solely at maximum power output through the greatest possible engine volume (e.g. Panhard, Lorraine-Dietrich), while other manufacturers ( e.g. Brasier, Renault, Darracq) accepted somewhat smaller cylinder dimensions in favor of a little more leeway in terms of chassis strength and optimization of load distribution.

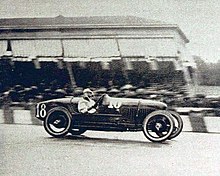

The undisputed first Grand Prix winner in history was Ferenc Szisz in a Renault, who comes from Hungary but lives in France, with an average speed of around 101 km / h, followed by Felice Nazzaro in a Fiat and Albert Clément in Clément-Bayard . Szisz, who drove in the great city-to-city races of 1902 and 1903 as a mechanic in the Louis Renault car, was thus also a prime example of the progressive professionalization of Grand Prix sport. In 1903 the German Automobile Club refused, for professional reasons, to start with Wilhelm Werner , the recognized best German driver, and Otto Hieronimus as “employees” in the German Gordon Bennett team, and instead preferred foreign gentlemen's drivers such as the Belgians Camille Jenatzy, Baron Pierre de Caters and the American Foxhall-Keene , son of the President of the San Francisco Stock Exchange, were given preference, industrial drivers employed by the automobile manufacturers - mostly former mechanics and chauffeurs - soon set the tone.

After French cars had been successful in all other important races in addition to the Grand Prix in 1906 (Renault had almost doubled its sales figures from 1,600 cars in 1906 to 3,000 the following year), the decision of the ACF to take the Grand Prix as its successor was an easy one to firmly establish its former big city races again in the future. This also began a process of identification, from which a standardized event format gradually developed over the years. In the first few years in particular, the Grand Prix races were subject to numerous changes. In the second edition, for reasons of practicality, they returned to the one-day race. At the same time, the Grand Prix found a new home at Dieppe with a significantly shorter but also more curvy triangular course .

Another expression of the search for suitable event modalities was the now beginning annual change of the racing formula. If the technical regulations had remained stable for five years in the form of the "1000 kg formula" introduced in 1902, this was replaced by a consumption formula for 1907 according to which each participant was entitled to 30 l of fuel per 100 km of route. This should actually reduce the existing over-motorization and ultimately also the tire wear, so that the cars should be more suitable for everyday use and races could be won more “on the track”. However, the formula missed its target, as the top teams had already stayed below this limit in 1906. At the second Grand Prix , the majority of “one-tonne vehicles” took to the starting line, albeit mostly with reinforcements on the chassis and further increased engine power due to the elimination of the weight limit.

The classic Grand Prix teams from Fiat, Darracq , Renault, Brasier and Lorraine-Dietrich decided the outcome of the race again. After a varied race, Nazzaro won in a Fiat ahead of last year's winner Szisz in a Renault and Paul Baras in a Brasier. None of the participants had any serious problems with fuel consumption. After the Targa Florio and the Kaiserpreisrennen, Fiat had won the third important race of the season - and thus among all three racing formulas used.

With the Coupe de la Commission Sportive , which was held at the same time , the ACF also defined a second car category, the race of which led over a shorter distance and for which fuel consumption was limited to 15 l per 100 km. The winner was a certain de Langhe on Darracq. At the same time, however, efforts were made in other countries to counter the Grand Prix with its own racing formats and formulas. In the USA, the races for the Vanderbilt Cup had been going on in front of an initially enormous crowd in front of the gates of New York City since 1904 , conceived as a kind of comparison between the continents with the aim of spurring the American automotive industry to better performance, and the Italian one With the limitation of the cylinder bore, the Targa Florio from 1907 was the first direct control of engine dimensions as the subject of a racing formula. In Germany, too, where an annual touring car race has been held since 1905 with the Herkomer competitions , the Kaiserpreis race of 1907 attempted a real alternative to the Grand Prix , with an impressive field of no less than 77 cars and of course also with its own racing formula, which with a displacement limit of 8 liters, a wheelbase of at least 3 meters and a minimum weight of 1175 kg should steer the direction more towards everyday touring cars. This development finally led to the Prince Heinrich rides from 1908 and further to the later rallies , but also had an impact on Grand Prix racing at least insofar as z. For example, separate runs for Grand Prix and Kaiserpreis cars were carried out both at the subsequent Ardennes race and at the Coppa Florio.

In order to put a stop to the impending fragmentation, the Grand Prix formula for 1908 was no longer adopted by the ACF alone. Instead, the representatives of the international automobile clubs agreed for the first time on a real "international" racing formula at a congress in the Belgian seaside town of Ostend . With this step, the role of the "Grand Prix races" as the epitome of the highest motorsport category was finally secured. Only in America has a racing car category established itself permanently against it with the Indy Cars , but at the American Grand Prize , the "European" Grand Prix rules were also used here.

In the racing formula that went down in automotive history as the Ostend formula , the cylinder bore was limited to 155 mm for four-cylinder engines (or 127 mm for six-cylinder engines) in addition to the specification of a minimum weight of 1100 kg. This should leave the designers free to choose between slow-running long-stroke engines with a large displacement and high-speed short-stroke engines. The limiting factors turned out to be the piston speed and the problems with cooling cylinders that were too long, so that the formula achieved its purpose of preventing further growth in engine size, which eventually leveled off at around 12 to 13 liters displacement.

After the race of 1907 - despite the success of a foreign racing team - was again a great public success, hardly any well-known automobile manufacturer could afford to stay away for 1908 . Even months before the race, extensive press coverage of the preparations of the individual manufacturers and the creation of their new racing cars began. Numerous models were specially developed for this competition and the teams traveled to the track weeks before the actual race date to complete an intensive program of training and test drives. The trend clearly pointed away from side-controlled engines towards OHV valve control , and there were even the first engines with overhead camshafts in the field.

No less than 51 cars from 17 manufacturers from six nations finally gathered for the start, with the foreign participants outweighing the number of locals for the first time. The intention of the racing formula was apparently also in this respect to make the Grand Prix a truly international event. On the other hand, the idea of the Grand Prix as a stage for the presentation of the products of the superior French automotive industry was lost. Ironically, the German arch-rivals - above all Mercedes - set new standards in terms of tactical preparation, organization and fine-tuning and the race even ended, to the general shock, with a German triple victory by Christian Lautenschlager in a Mercedes ahead of Victor Hémery and René Hanriot in a Benz . Mercedes had succeeded in compensating for the performance disadvantage of the still side-controlled engines with a particularly light and compact design, balanced weight distribution and optimal coordination of the car with the conditions on the route.

For 1909 , a further tightening of the racing formula was originally planned by limiting the bore to 130 mm while reducing the minimum weight to 900 kg. After two years in Dieppe, the venue for the Grand Prix should now have changed to the Circuit d'Anjou near Angers . But after the defeat of 1908, which was perceived as a humiliation, the established French automobile companies - who were also involved in internal quarrels among each other - shied away from participating in the face of the risk of further loss of face. In any case, the market for luxury vehicles was currently largely saturated, so that the trick of boosting sales through Grand Prix victories is no longer correct for traditional manufacturers such as Panhard, Mors or Lorraine-Dietrich, but also for top foreign brands such as Mercedes or Fiat worked. An agreement between the manufacturers finally resulted in the cancellation of the race for 1909, just as the Grand Prix activities in Europe practically came to a complete standstill for a while.

On the other hand, it was precisely at this stage that Grand Prix races flourished briefly but intensely in the United States. American designs had taken part in the Gordon Bennett and Grand Prix races again and again since 1900, but neither there nor in the races for the Vanderbilt Cup on Long Island had they presented any serious competition for the European makes. Most of them were more or less modified production models that were no match for the thoroughbred racing cars from Europe. Nevertheless, it was in the USA at the end of 1908 on the Savannah-Effingham Raceway , a road circuit near Savannah in the state of Georgia with the Grand Prize of the Automobile Club of America (often referred to as the American Grand Prize in literature) for the first time the term Grand Prix in the title carried out outside France. Due to the attractive prize money, practically the entire European elite had come and accordingly the local representatives were once again lost from the start, although among them the Chadwick Six , driven by Willie Haupt, was the first racing car with a supercharged engine at a Grand Prix race started. The victory went to Fiat driver Louis Wagner in front of Victor Hémery and Felice Nazzaro. In 1909 the race was canceled due to disputes in the association and in 1910 the event was only secured so late that only Fiat and Benz were able to send cars from Europe in time. In the end, however, the driver of a European make, the American David Bruce-Brown , to whom Benz had provided a car this time, won again. It is reported that the runner-up, Bruce-Brown's team-mate Hémery, is said to have poured champagne over the American at the award ceremony; this was possibly the first case of such a “champagne ceremony” in a Grand Prix race. Bruce-Brown was again the winner of the American Grand Prize in 1911 , this time - in the absence of any restriction by a racing formula - on a Fiat with gigantic dimensions. In general, the European companies had meanwhile started more and more to only bring their cars to America and then make them available to local drivers there.

In the meantime, however, a development had helped to slowly put an end to the brief heyday of the American Grand Prix races in those early years. After the first permanent racetrack opened in Brooklands in Great Britain in 1907, the first such “racetrack” opened in the USA in 1909, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway . In contrast to the classic circuits on public roads, these were stadium-like systems, where the spectators could see large parts of the mostly quite simple route from fixed stands (although the shape of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, strictly speaking, was more like a rectangle or Trapezoid with rounded corners, the term oval has become common for such routes ). This new form of motorsport quickly gained popularity, especially in the United States, so that the 500-mile race in Indianapolis , which had been held since 1911, quickly became the main event of the year there and the Grand Prize more and more overtook the rank. When, a short time later, Grand Prix races were held again in Europe, it only led a shadowy existence for a few years without significant European participation and was finally stopped entirely in 1917 with the entry of the USA into the First World War .

→ Seasonal reports: 1906 , 1907 , 1908 , 1909 , 1910 , 1911

Resumption of Grand Prix races (1911–1914)

In the history of Grand Prix racing, it has often been the case that in times of crisis other, supposedly “subordinate” racing categories came to the fore all the more successfully. The first "Grand Prix-free" period from 1909 to 1911 was an early example and the first heyday of the so-called Voiturette class developed in these three years . At the same time, this was also a reflection of a general development in which the automobile increasingly lost its exclusivity as a toy for wealthy rulers and, in contrast, smaller and therefore more economical models in everyday use for working medium-sized companies - doctors, sales representatives, etc. - more and more in the Moved to the fore. In 1906, the magazine l'Auto organized the Coupe de l'Auto (often referred to as Coupe des Voiturettes ), the first major race for this vehicle category. Compared to the Grand Prix class, the participating cars were lighter and less motorized, but high-performance models specially developed for racing. Despite a few excesses in the regulations - the initially only limited bore with an approved stroke soon led to sometimes extremely long-stroke, sometimes tower-like cylinder designs - this race, as well as its new edition in the following year, were so successful that in 1908 the ACF itself finally also devoted itself to this car category and held a Grand Prix des Voiturettes on the day before its real big race .

In this way, from 1909 the races for the Coupe de l'Auto became the new highlight of every racing season. At the same time, completely new automobile brands such as Lion or Lion-Peugeot (Peugeot's brand for light automobiles), Sizaire & Naudin , Delage , or soon Hispano-Suiza came to the fore, while already among the established Grand Prix manufacturers such legendary names as Panhard & Levassor, Mors, Clément-Bayard or Renault disappeared from the Grand Prix stage for good. An interesting development was that many of the new companies refrained from designing their own motors and instead relied on third-party products - primarily built-in motors from de Dion-Bouton . In a way, this represented an anticipation of the use of Coventry-Climax or Ford-Cosworth engines by numerous Formula 1 teams in the 1960s and 1970s.

In the meantime, however, the ACF came under increasing pressure, as its actual task was seen in the implementation of the annual "big race". After a three-year break, the club announced a new Grand Prix formula for the first time in 1911 , in which the cylinder dimensions were limited to 110 mm bore and 200 mm stroke for a total displacement of approximately 7600 cm³. However, the response from the manufacturers remained very low and so under the title Grand Prix de France (not to be confused with the Grand Prix de l'ACF ) only a formula-free race took place, that of the Automobile Club de l'Ouest - and thus without direct involvement of the ACF - at the location of the first Grand Prix of 1906 at Le Mans. The racing cars based on the new Grand Prix formula only formed their own sub-category, which was, however, sent into the race together with cars of all classes. The questionable importance of this event is underlined by the fact that in second place was the Bugatti of the Alsatian driver Ernest Friderich with an almost tiny engine of 1.3 liters displacement - about a tenth of the engine size of the victorious Fiat by Victor Hémery - came to the finish.

In 1912 the ACF made another attempt, this time wisely without any given racing formula. As if that weren't enough, the race was merged with this year's Coupe de l'Auto (for so-called "light cars" up to 3 liters as the successor category of the Voiturettes ) due to concerns about insufficient participation . In view of such fears, it seems almost ironic that from now on up to five cars per team have been admitted to the Grands Prix, but this quota was not fully used by any of the manufacturers. The overall sizeable field of over 40 cars ultimately conceals the fact that the actual Grand Prix class with 14 participants was actually only very weak. Nevertheless, this still rather timid new beginning heralded the first fundamental generation change in racing car construction. While the established manufacturers still competed with cars of the tried and tested design - four-cylinder with over 14 liters displacement - a new challenger entered the Grand Prix stage with Peugeot, who brought with him the latest state of engine technology when he rose from the voiturette category: The Peugeot EX1 or L-76 with a displacement of "only" 7.6 liters is considered to be the first "modern" Grand Prix construction in history, whose construction principle - spherical combustion chambers with four positively controlled valves per cylinder and valve train via two overhead camshafts - has since been found in practically all racing engines. Georges Boillot succeeded at the end of the race again (as last in 1906) over two days as the first French Grand Prix winner ever to win over the comparatively powerful Fiat, even if they had initially determined the course of the race.

This began a period of Peugeot dominance, whose cars also won the second race of the year for Grand Prix cars with the Coupe de la Sarthe (in the context of which the second Grand Prix de France was held this year as a special rating for Voiturettes ) and in the following year became the first European team to win in Indianapolis. During this time, Peugeot also introduced other innovations in Grand Prix racing, such as the conversion of the engines to dry sump lubrication , the use of a wind tunnel to optimize the vehicle's aerodynamic shape and, in particular, the introduction of four-wheel brakes (until then, the cars were mostly just over gear brakes acting on the drive wheels are braked). In general, the racing cars were now aerodynamically better designed and now had real bodies that were more than the rudimentary fairings of the early Grand Prix models. In addition, removable wheels were now also permitted, which significantly accelerated the pit stops, and an expression of the further increasing internationalization and professionalization was that the teams no longer proceeded primarily according to national criteria when selecting tire manufacturers, but now also select the best across national borders Contract offers followed. For example, in 1913 Peugeot switched from “German” Continental tires to “Italian” Pirellis and then in 1914 to the British brand Dunlop .

After the very interesting course of this first new edition, the ACF slowly took more courage and wrote the Grand Prix of 1913 as an independent race again, which for the first time since 1907 no longer in Dieppe, but on a new course, the Circuit de Picardie in was held near Amiens. For a change, the Commission Sportive of the ACF once again relied on a consumption formula that was combined with a weight restriction. With a permissible car weight between 800 and 1100 kg, the participants were not allowed to use more than 20 liters of fuel per 100 kilometers of racing - a reduction of 33% compared to the 1907 formula. This was intended to prevent oversized engines on the one hand and overly fragile constructions on the other.

Naturally, under these regulations, the more efficient modern engine concepts had an advantage over the traditional "displacement monsters", whose days were now finally numbered. Peugeot meanwhile achieved performance values of 20 hp per liter displacement, while z. B. the victorious Fiat of 1907 only had 8 hp per liter. The "traditional companies" left the field completely to the "upstarts", of whom Delage, Peugeot's toughest competitor in the Voiturette class, has now made the rise to become a Grand Prix manufacturer. With Sunbeam , a reasonably competitive British racing team was added for the first time. With a total of 20 cars from eight different manufacturers from five nations, the field of participants was rather average because, not least because of the absence of Fiat and Mercedes, the big foreign names were missing. Nevertheless, there was an exciting battle for the top between the two leading French brands, which in the end was again last year's winner Boillot with a full 15 seconds ahead of his teammate Jules Goux in the narrowest outcome of a Grand Prix race to date for Peugeot. Boillot was thus also the first driver to record two Grand Prix victories, and thus finally became a folk hero in his homeland, one of the first superstars of Grand Prix sport.

With this success, Peugeot was of course again clearly favored for 1914 , even if the two main foreign opponents, Mercedes and Fiat, who had caused the two most painful defeats of the French Grand Prix companies in 1907 and especially in 1908, were again involved . The ACF had also reshuffled the cards and, in addition to another change of the venue ( Lyon ), now for the first time set a general displacement limitation to 4.5 liters as a racing formula with otherwise completely approved cylinder dimensions and a weight limit of 1100 kg. 14 automobile manufacturers from the six traditional European automobile nations (France, Germany, Belgium, Italy, Great Britain and Switzerland) answered the call and submitted entries for a field of no less than 41 participants, among them practically all the big names in automobile sport - including also all four previous Grand Prix winners - were represented. In a tense atmosphere on the eve of the First World War - just a week earlier , the Austrian heir to the throne Franz Ferdinand had been murdered in Sarajevo - and in front of an impressive backdrop of 300,000 spectators, the stage was set for a new high point in Grand Prix history, which took place in the episode was often referred to as the "greatest" race ever.

While Peugeot, like Delage and Fiat, once again seemed to have a technical advantage through the use of four-wheel brakes for the first time, Mercedes, for its part, relied on consistent lightweight construction while at the same time dispensing with the last technical refinements, as well as particularly careful tactical preparation for the race - virtues that had already led to success in 1908. For the first time, scheduled tire changes were planned from the outset in order to avoid tire damage on the route - and thus a correspondingly greater loss of time - as far as possible. In the end, this calculation worked out perfectly and so the Mercedes team - this time with Christian Lautenschlager, Louis Wagner and Otto Salzer even with a triple victory - the French manufacturers once again suffered another major defeat. Less than four weeks later, however, the war broke out and completely pushed motorsport out of the general perception. Only in the United States were racing operations continued until they entered the war in 1917.

→ Seasonal reports: 1911 , 1912 , 1913 , 1914

The rise of the Italians (1919–1924)

While Indianapolis was already driving again in May 1919, motor racing in badly shaken Europe only got back on track very slowly after the First World War . As the first major race, the Targa Florio was not driven again until over a year after the end of the war in far-away Sicily , just as a notable racing operation was initially started mainly in Italy. In France, on the other hand, only the Coupe des Voiturettes (with Ernest Friderich in a Bugatti as the winner) took place as a kind of “test run” in 1920 . However, it took until 1921 for the ACF to host a real Grand Prix again . There were starting this year, now even a second such major event: As part of the race weekend of Brescia also a race for the first time became the Gran Premio d'Italia down.

During the Grand Prix de l'ACF was initially in the almost annual exchange continues to take place on traditional road courses, his Italian counterpart found from the following year his - with a few exceptions - permanent home to the newly created race track of Monza . The Autodromo di Monza is thus the first specially built for Grand Prix races and thus also the oldest still in use facility of this type and at the same time was also the first race track ever used for a Grand Prix with a completely paved surface. This gave the Italian Grand Prix a completely different character in terms of infrastructure and spectator-friendliness, but last but not least, the racing itself, because the short distance of just 10 km lap length with its comparatively high proportion of straights and fast corners completely different requirements of people and material than was the case on the classic street courses. Only gradually were further, more or less similarly designed permanent Grand Prix circuits added, which were, however, repeatedly criticized because of their supposedly insufficient driving demands. However, the ACF now also chose significantly shorter circuits, so that the lap lengths leveled off at the (from 1922) generally prescribed total distance of 800 km at 10 to 25 km.

One of the most groundbreaking innovations in the conduct of the Grand Prix was the transition to the mass start for the first time at the French Grand Prix of 1922 was applied. In contrast to the previous practice of starting the racing cars individually or in pairs at certain time intervals, all participants were now sent into the race simultaneously from a common starting formation, albeit initially in the form of a "rolling" start . It was only with this change that circuit races got their format, which is still used today, in which the fight for positions is comprehensible at all times for both participants and spectators, even without a stopwatch, and the first at the finish is automatically the winner of the race. The positions on the starting grid were initially usually determined by drawing lots.

Of course, the introduction of a second Grand Prix was also an expression of a certain loss of status for the ACF, which soon became just a national automobile association among several peers. Accordingly, the need arose to regulate the racing formula, uniform racing distances and, above all, the scheduling from now on on an international level. For this purpose, the AIACR founded the Commission Internationale Sportive (CSI) in December 1922, chaired by the racing driver pioneer Baron René de Knyff . As one of its first decisions, this commission decided to award one of the Grands Prix the honorary title of a Grand Prix of Europe every year from now on . As a kind of race of the year, this should take the rank that had previously been awarded to the Grand Prix de l'ACF alone. The first choice was the Italian Grand Prix in 1923 , followed by France (1924) , Belgium (1925) and Spain (1926) .

Unlike in the pre-war period, the holding of such large racing events was no longer called into question from year to year. Instead, Grand Prix races have been an annual normal since 1921, which so far has only been interrupted once by the Second World War. With a general increase in racing, also at the local and regional level, the grand prizes in the early 1920s were still the absolute highlights of the season, despite the occasional sparse starting fields, which were accompanied by months of extensive reporting. Nationalism was still very pronounced, although France's arch-rival Germany had not yet been re-accepted into the AIACR after the end of the First World War. The national automobile clubs were therefore able to decide for themselves when organizing their Grands Prix whether they would allow racing cars from Germany or not. France and later Belgium in particular remained very restrictive for a long time, while Mercedes was allowed to take part in the Targa Florio again in spring 1922 and entries from German manufacturers were also accepted for the Italian Grand Prix .

Overall, however, the Grand Prix participation of European automobile companies remained significantly lower than in the pre-war period. The starting fields were usually between 10 and 20 participants, at the 1921 Italian Grand Prix there were only two teams with three cars each. A major reason for this was the technical and industrial progress triggered by the war. On the one hand, many armaments companies set up for mass production switched to the series production of primarily cheap, easy-to-manufacture car models for everyday use, on the other hand, a rapid technical development had taken place, especially in aircraft engine construction, which now also led to extremely complex and expensive high-performance designs in racing car construction . As a result, participation in Grand Prix races was only of interest to a few automobile manufacturers who were willing to bear the development costs. High-compression six and eight-cylinder engines that easily reached speeds of over 4000 revolutions per minute were now standard. The compressor supercharging, which Mercedes used for the first time in the 1922 Targa Florio, also took over from aircraft engine manufacturing, led to another real leap in performance. After the first victory of Fiat with supercharged engines at the Italian Grand Prix in 1923, there was no Grand Prix success for a racing car with an uncharged naturally aspirated engine until the beginning of the Second World War. The triumphant advance of the compressor also meant the end of some interesting aerodynamic and chassis technology approaches, such as the Bugatti Type 32 "Tank" with a fully clad, streamlined body , the Voisin Laboratoire with an early wooden monocoque construction taken from aircraft construction, or the Benz teardrop car , the first Grand Prix racing car with a mid-engine . However, none of these designs were able to compensate for the power boost of the supercharged engines, as was the Delage 2LCV , the first twelve-cylinder in Grand Prix history, whose impressive V12 DOHC engine, which was highly complex for the time, was regarded as a masterpiece of engineering has been.

While the European manufacturers were initially reluctant, teams from the United States also started more frequently in the early 1920s. This was made possible because the racing formula introduced for Indianapolis in 1920 with a displacement of 3 liters and a minimum weight of 800 kg had also been adopted for the European races in 1921. With Jimmy Murphy on Duesenberg , an American driver was able to compete for the first time at the first Grand Prix de l'ACF of the post-war period (and for a long time only for a long time until Dan Gurney in an AAR Eagle at the Belgian Grand Prix in 1967 ) add an American brand to the list of winners. Against the American eight-cylinder racing cars with their hydraulic brakes, the bolides of the French Ballot racing team, developed by the former Peugeot designer Ernest Henry , to the disappointment of the local audience on the new circuit of Le Mans, came up short after the Americans followed had left again, finally to success at the first Italian Grand Prix in Brescia over the Fiat team, which was participating there for the first time again.

Its heyday began with the introduction of the new racing formula in 1922 , in which the displacement and minimum weight were now reduced to 2 liters and 650 kg, respectively. This meant that the engine size was more than halved compared to 1914, while at the same time the minimum distance for the Grands Prix was set at 800 km. As a result, 15 manufacturers registered for one of the two Grand Prix races of the year, including for the first time Bugatti , which had now become a purely French brand after the transfer of Alsace-Lorraine . At the season opener in Strasbourg , Fiat's new six-cylinder model Tipo 804, despite some technical problems and despite the fatal accident of Biagio Nazzaro (nephew of the winner Felice Nazzaro), was so oppressive that most companies immediately decided to take part in the Italian Grand Prix canceled again. A Fiat victory was practically certain there, too, before the inauguration race in Monza. Pietro Bordino , who is regarded as one of the best racing drivers of this era, won by a large margin over his team-mate Nazzaro and the Bugatti driver Pierre de Vizcaya . A special feature of this race was that, contrary to the usual practice, all participants were flagged immediately after the winner had crossed the finish line, even if they had not yet covered the full race distance.

Despite the somewhat disappointing course of the 1922 season, the CSI apparently viewed the existing 2-liter formula as a success and made the decision to extend it up to and including 1925 . For the first time, manufacturers were offered the security of being able to use the increasingly expensive and complex racing car designs over a longer period of time instead of just once or twice. For the French Grand Prix of 1923 , Fiat returned with a groundbreaking new design, the Tipo 805 , the first supercharged Grand Prix car. However, the Italian racing cars, which for a long time looked like certain winners, were all thrown out of the race on the new circuit near Tours due to engine defects because their compressors were not adequately protected against the intake of dust and stones. This cleared the way for the first - and for many years only - victory by a British driver on a British make, Henry Segrave on Sunbeam, which was essentially a copy of the Fiat design from the previous year. The racing cars from Bugatti and Voisin with their revolutionary vehicle concepts, which were very futuristic at the time , remained far behind due to their inadequate engine power.

Until the home race in Monza Fiat had but get the problems by using other compressors under control and since both Sunbeam after the victory at the French Grand Prix and Bugatti were virtually certain defeat out of the way and also the first time An incoming team of Alfa Romeo to After the fatal training accident of Ugo Sivocci withdrew his model P1 racing car , which was also equipped with compressors, Carlo Salamano's Fiat victory in the first European Grand Prix was no longer in danger. Sunbeam, on the other hand, took the opportunity and came a little later at the first edition of the Spanish Grand Prix at the new Autodrom of Sitges-Terramar near Barcelona (whose status as a Grande Épreuve in literature is, however, controversial) after a lap-long thrilling Fight against the American Miller racing car designed for such oval courses by Louis Zborowski , an Englishman of Polish descent, to yet another success of the season.

In 1924 , however, Fiat domination was abruptly ended. The main reason for this was the constant departure of key personnel, which was increasingly being lured away by competing companies. In the previous year, the former Fiat engineer Vincenzo Bertariore had already put the successful copy of the Tipo 804 from 1922 on the wheels for Sunbeam. In 1923, not least at the instigation of the then Alfa Romeo driver and later company founder Enzo Ferrari , who thus appeared for the first time in Grand Prix history, Fiat chief designer Luigi Bazzi , but above all the highly talented, changed later star designer Vittorio Jano to Alfa Romeo , where they put the new Alfa Romeo P2 , of course also with an in-line eight cylinder and compressor, on the wheels. Fiat, on the other hand, had no choice but to start the season with practically unchanged models from the previous year.

At the Grand Prix de l'ACF of 1924 , which was once again held near Lyon, but now for the first time on roads with paved roads throughout, the competition among the participants was higher than it has been in a long time. The cars from Sunbeam, Fiat and Alfa Romeo were alternately in the lead, with slight advantages for the cars from Milan , and Delage was also able to keep up with the uncharged V12 engine despite the power deficit. After an exciting seven-hour race, in which Fiat and Sunbeam were increasingly experiencing technical problems, Alfa Romeo driver Giuseppe Campari finally crossed the finish line for his first Grand Prix success two days ago. Fiat director Giovanni Agnelli was so angry about the circumstances of the defeat that he finally announced the complete withdrawal of his company from the Grand Prix sport in the run-up to the Italian Grand Prix. Alfa Romeo only encountered relatively weak competition at its home race, mainly from the Mercedes team, which was participating again for the first time after the war. The new eight-cylinder racing cars designed by Ferdinand Porsche , however, still showed considerable deficits in handling and were finally taken out of the race after Louis Zborowski's fatal accident. Alfa Romeo came to the end of a triumphant season with Antonio Ascari , Louis Wagner, Giuseppe Campari - who was replaced at the wheel during the race by Cesare Pastore - and Ferdinando Minoia to the first quadruple victory of a brand in Grand Prix history.

Below the Grand Prix level, a displacement limit of 1.5 liters became the de facto standard for the Voiturette category in the 1920s . Analogous to the real Grand Prix sport, the factory racing teams set the tone here too and the races, which were very popular in France in particular, were dominated by Talbot and Bugatti, with the exception of individual appearances by Fiat , whereby the manufacturers also meet here directly if possible avoided. One class lower, two other French companies fought for supremacy in the so-called cycle car class up to 1.1 liters displacement: Amilcar and Salmson . In Italy in particular, another trend developed, which had its origins not least in the Targa Florio . Many older Grand Prix racing cars were now in private hands here, and they regularly competed with the works teams in the classic racing in Sicily. Little by little, a series of “Everyman” races developed in which the participants could compete against each other with cars of all categories and cubic capacities that they could get their hands on. In the heyday of these so-called Formula Libre - that is, formula- free - races, from 1923 onwards, drivers increasingly began to acquire racing cars of foreign origin, so that the level of these events increased significantly.

→ Seasonal reports: 1919 , 1920 , 1921 , 1922 , 1923 , 1924

The first world championships (1925–1927)

As with many other disciplines, the idea of international championships had come up several times in automobile sport in the early 20th century. In February 1925 , at the instigation of the Automobile Club of Italy - the Italian racing teams were now clearly setting the tone in international races - the AIACR announced the introduction of an official world championship. As with the Grand Prix in general, only automobile companies could participate, so it was a brand world championship . From the combination of compulsory events (different depending on the manufacturer's country of origin), deletion results and a point system that took some getting used to - in principle, the best placements of a brand were added together so that the lowest total number of points was decisive for the awarding of the title - a complex and Opaque championship regulations that motorsport historians have so far not been able to fully understand in view of the scarce public relations work of the AIACR.

Of course, the three official Grand Prix of the season ( France , Italy and, for the first time, Belgium and Europe ) were designated for the races , and - to do justice to the name World Championship - the Indianapolis 500-mile race was the most important American racing event, which is why it was often referred to as the "Grand Prix" in press coverage. After all, in the applied since 1923 in the United States International Formule (the International Grand Prix Formula ) fixed displacement limit of 2 liters, while in return, now the Europeans taking along a mechanic on board (in this case still remains two-seater) racing cars waived. Despite this alignment of the regulations, only a few racing teams on both continents were still willing to undertake the time-consuming voyage to the other side of the Atlantic.

In addition, there were more and more races in Europe that had the title “Grand Prix” in their title, but otherwise had little in common with the objective of the official International Grand Prix as a competition for the automotive industry. These were mostly events with a more or less regional reference ( Grand Prix de Provence , Grand Prix de la Marne , Gran Premio di Milano , etc.), which were also available as formula -free races ("Formula Libre") for the increasing number of private drivers were open to racing cars of all kinds, or, like the Grand Prix des Voiturettes, were only reserved for subordinate vehicle categories. The organizers were free to decide on the format of the event, the class division and all other provisions, as well as who they invited to participate in their races. Grand Prix races in countries that were not considered to be among the “big” automobile nations (Sweden, Switzerland, Poland, Brazil, the North African colonies, etc.) were also not yet considered to be of equal rank. The German Grand Prix, which was also held for the first time in 1926, was regularly held as a sports car race in its early years , not least to protect German manufacturers from competition from highly developed foreign racing cars. With the Nürburgring , inaugurated in 1927 , a permanent racetrack was opened here, which, in contrast to other artificially created racetracks (Monza, Montlhéry , Brooklands , Indianapolis, or the Berlin Avus , which opened in 1921 ), has the route of a classic street course with numerous "natural" curves, Inclines and declines.

To distinguish it from such a proliferation of event titles and sets of rules, the generic term Grandes Épreuves (in German Great Examination ) developed for the classic Grand Prizes officially approved by the AIACR from around the mid-1920s , with certain privileges - in particular, priority over all other motor sport events in the calendar adopted annually by the CSI - but also the obligation to hold the races according to the applicable International Grand Prix racing formula ("Formule Internationale") and still only allow works teams to participate. The growing number of Grand Prix races, as well as the increase in racing operations as a whole, inevitably led to a certain decrease in attention to the respective individual event. The racing teams now usually no longer had time for weeks of test and training programs on the various Grand Prix tracks, especially when the races were taking place abroad, and sometimes only traveled with very small delegations or, in individual cases, even left local private drivers Start up “on behalf” of the plant.

There were few changes, especially in the last season of the 2-liter formula, which expired in 1925. The clear aspirant for the world championship title was Alfa Romeo with last year's successful model, the Alfa Romeo P2 , with which the team then also won the two Grand Prix in Belgium and Italy . The only serious competitor would have been Delage , where the V12 engine was finally also equipped with a compressor over the course of the season and thus penetrated into previously unattained performance regions. Despite the "given" victory in the French Grand Prix (after Alfa Romeo had taken the car out of the race there after Antonio Ascari's fatal accident), and although they were even at the top of the intermediate championship standings before the last race, However, the team finally fell completely out of the classification due to the fact that they did not compete in the mandatory Italian Grand Prix. Behind world champion Alfa Romeo, second place went to the US manufacturer Duesenberg, who had also won the race in Indianapolis. Third was Bugatti , where they still refused to use the compressor and did not really take part in this first world championship. Instead, the focus was now on the marketing of the Bugatti Type 35 , the world's first freely available Grand Prix car. Private owners soon drove from success to success at countless smaller events all over Europe on this model, which was soon to be available with various engine variants and was characterized primarily by simple handling and easy maintenance.

Grand Prix racing , on the other hand, headed towards a new low point in 1926 with the switch to the new 1.5-liter formula. It was precisely the reduction in displacement that meant that more effort was made in engine development to achieve a performance advantage, and not all of the automotive companies involved so far were prepared to practically start all over again in such an arms race. Above all, Alfa Romeo found itself in economic difficulties and after winning the world championship actually had nothing more to prove, so that in Grand Prix racing there were only three manufacturers left with Delage, Bugatti and Talbot . Worse still, both Talbot - which had previously represented the Franco-British STD group very successfully in the Voiturette class and now consequently replaced Sunbeam as the in-house Grand Prix brand - and Delage reached their limits with their extremely sophisticated models economic opportunities. Not only did this delay the car's readiness for racing for months, but in the end the development of the racing car even put the existence of both companies in serious danger.

What was particularly striking about the new racing cars from both companies was the extremely low chassis construction. Without the need to accommodate a passenger on board, the drive train could now be moved sideways past the driver so that a lower seating position was possible. In addition to lowering the center of gravity, this also led to a significant reduction in the frontal area and thus the air resistance. In addition, with the newly developed short-stroke inline eight-cylinder, with which the magical value of 100 hp per liter displacement was exceeded for the first time, a real leap in speed and performance was achieved again, so that the new racing cars were practically as fast again as their larger displacement cars Predecessor.

Bugatti, on the other hand, chose a simple but pragmatic approach and presented the Type 39A, a version of the tried and tested Type 35 that is now finally also compressor- charged and reduced to 1.5 liters . At the beginning of the 1926 season, it was the only team ever able to compete in the 1926 Grand Prix de l'ACF . The race on the Miramas oval course, which is not particularly demanding in itself, is therefore considered to be a low point in Grand Prix history, in which Jules Goux did his laps practically all the time due to technical problems of his two teammates and in the end he was the only one came into the evaluation. At least the European Grand Prix in San Sebastián , Spain , went a little better , with at least a second team at the start, even if the new Delage Type 15 S 8 was slowed down by a serious design error. The incorrectly positioned exhaust caused the cockpits to heat up to such an extent that the drivers regularly even suffered burns and constantly had to come to the pits to change drivers. Goux on Bugatti achieved a second win in a row ahead of Delage , who was driven alternately by Edmond Bourlier and Robert Sénéchal . The Spanish automobile club had prudently decided beforehand to hold the actual Spanish Grand Prix as a Formula Libre race a week later in order to get a reasonably adequate field of participants. With the victory of the later team boss Bartolomeo "Meo" Costantini, this race also became a clear Bugatti affair, with at least ten cars at the start, the European Grand Prix as the official Grande Épreuve was clearly surpassed.

For the British Grand Prix on the venerable Brooklands track, Talbot also brought his team to the start for the first time this season, but all three racing cars were slowed down due to a design fault on the front axle and retired from the race prematurely. Delage, on the other hand, finally achieved its first success of the season, but although the drivers suffered less from the conditions in the cooler English climate than in the heat of Spain, Sénéchal and Wagner had to take compulsory breaks at the wheel of the victorious car again and again to cool their feet . In view of these circumstances, both Delage and Talbot subsequently decided not to make the season finale at the Italian Grand Prix in Monza, especially since Bugatti was already world champion based on the results so far. Here too, with only six participants - including two racing cars from the new Maserati brand for the first time at a Grand Prix - a completely safe Bugatti victory was achieved. After all opponents were canceled , “Sabipa” , who started under a pseudonym, and Bartolomeo Costantini were able to do their laps on their own for almost the entire second half of the race. In retrospect, it seems astonishing that the Grand Prix races were still followed with great interest by the spectators despite such disappointing performances.

In 1927, the year of the last fully played World Championship for the time being, Delage finally got the problem of cockpits overheating under control. Chief designer Albert Lory had quickly turned the cylinder head of the engine so that the exhaust could now be routed along the opposite side of the vehicle, further away from the pilot's feet. Now the real potential of the car could finally come into its own and Robert Benoist was successful in all four grand prizes of the season. Right at the start of the season at the French Grand Prix as well as at the final in Great Britain , the team was even able to record a triple victory. After Talbot had previously stopped racing during the season for financial reasons and Bugatti also mostly avoided direct confrontation, the world championship was decided early in the season. Having reached the goal of his long-term endeavors, Louis Delage announced the withdrawal of his factory, so that not only the 1.5-liter formula, but also the Grand Prix sport in its previous form no longer had any prospects.

→ Seasonal reports: 1925 , 1926 , 1927

The "formulaless" years (1928–1933)

The period between 1928 and 1933 marks one of the most drastic upheavals in Grand Prix racing. After Talbot and Delage had withdrawn, only Bugatti remained as the last well-known manufacturer in the 1928 season , which meant that the concept of competition among automobile companies that had been the basis since the first Grand Prix in 1906 could practically no longer be maintained. Instead, in a conversion process lasting several years, in which there were three unsuccessful attempts until 1930 to somehow continue the old-style brand world championship, the completely contrary idea of the so-called "free formula" ("Formula Libre") finally prevailed. This type of race had its origins in events such as the Targa Florio and enjoyed steady popularity from around the mid-1920s - as the crisis in official Grand Prix sport progressed - initially primarily in Italy, but increasingly also in France, both the number of races, as well as the size and composition of the starting fields and, last but not least, the audience interest. Soon races like the Coppa Acerbo in Pescara, the Coppa Montenero in Livorno, the Premio Reale di Roma , or the Grand Prix de la Marne in Reims developed into real classics with fixed dates in the annual racing calendar. With the Grand Prix of Tripoli on the specially built Mellaha racetrack , the leap to the North African colonies was made, which was soon followed by the Grands Prix of Tunis and Algiers on the French side .

Participation in such races was practically possible for anyone who had a suitable racing vehicle, as was the case above all with the various versions of the Bugatti Type 35, which is freely available for sale. Maserati soon followed suit and began to manufacture small series racing cars for paying customers. In addition, there were the former Grand Prix racing cars from Delage, Talbot and Alfa Romeo, which now increasingly also came into private hands, since the factories no longer had any use for them. The fields were completed by a hodgepodge of voiturettes , self-made racing cars, makeshift converted sports cars and other vehicle models of all types and engines. In order to create a certain equality of opportunity in view of such diversity, there were usually class divisions according to cubic capacity (usually up to 1100 cm³, 1500 cm³, 2000 cm³, 3000 cm³ and above) for which, in addition to the overall classification of a race, separate ratings were usually made .

After some hesitation, this principle of success finally became - after only a corridor for minimum and maximum weight had already been specified in the International Racing Formula for 1928, the old idea of a consumption formula was once again clung in vain for 1929 and 1930 - also by the AIACR as accepted the new Grand Prix format, and even if the national organizers of the Grand Prix continued to handle the admission of “independents” very differently, it should essentially remain in place for the next 50 years. Only with the transformation of Formula 1 into a closed racing series reserved for the “constructors” organized by the FOCA did they finally return a little to the original approach at the beginning of the 1980s, even if the image of automobile racing has of course changed fundamentally in the meantime would have. With the introduction of Formula Libre , the paths separated again between Grand Prix racing, which was predominantly European in character, and racing in the USA, where Indianapolis initially continued with the previous 1.5-liter racing cars and soon afterwards was completely independent Racing formulas was driven.