Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War from 1618 to 1648 was a conflict over hegemony in the Holy Roman Empire and in Europe that began as a religious war and ended as a territorial war . In this war the French-Habsburg antagonism erupted at the European level and the antagonism between the Emperor and the Catholic League on the one hand and the Protestant Union on the other. Together with their respective allies, the Habsburg powers supported Austria and SpainIn addition to their territorial as well as their dynastic conflicts of interest with France , the Netherlands , Denmark and Sweden, they predominantly took place on the soil of the Empire. As a result, a number of other conflicts were closely related to the Thirty Years War:

- the Eighty Years War (1568–1648) between the Netherlands and Spain,

- the Upper Austrian Peasants' War (1626)

- the Mantuan War of Succession (1628–1631) between France and Habsburg,

- the Franco-Spanish War (1635-1659)

- the war for supremacy in the Baltic Sea region ( Torstensson War ) (1643–1645) between Sweden and Denmark.

The fall of the window in Prague on May 23, 1618, with which the uprising of the Protestant Bohemian estates broke out openly, is considered to have triggered the war . The uprising was directed mainly against the new Bohemian King Ferdinand of Styria (who intended the re-Catholicization of all the countries of the Bohemian crown ), but also against the then Roman-German Emperor Matthias .

Overall, in the 30 years from 1618 to 1648, four conflicts followed each other, which historians termed the Bohemian-Palatinate, Danish-Lower Saxon, Swedish and Swedish-French wars after the respective opponents of the emperor and the Habsburg powers. Two attempts to end the conflict (the Peace of Lübeck in 1629 and the Peace of Prague in 1635) failed because they did not take into account the interests of all directly or indirectly involved. This only succeeded with the pan-European peace congress in Münster and Osnabrück (1641–1648). The Peace of Westphalia redefined the balance of power between the emperor and the imperial estates and became part of the constitutional order of the empire that was in force until 1806. In addition, it provided for territorial cessions to France and Sweden as well as the withdrawal of the United Netherlands and the Swiss Confederation from the Reichsverband.

On October 24, 1648, the war ended, the campaigns and battles of which had mainly taken place in the area of the Holy Roman Empire. The acts of war and the famines and epidemics they caused had devastated and depopulated entire regions. In parts of southern Germany only a third of the population survived. After the economic and social devastation, some of the war-hit areas took more than a century to recover from the aftermath of the war. Since the war took place predominantly in German-speaking areas, which are still part of Germany today, the experiences of the war, according to experts, led to the anchoring of a war trauma in the collective memory of the population.

History and causes

In the run-up to the Thirty Years' War, a diverse field of tension consisting of political, dynastic, denominational and domestic political contradictions had built up in Europe and the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. The causes go back a long way.

Power relations in Europe

In the period before the Thirty Years' War there were three main areas of conflict: Western and northwestern Europe, Northern Italy and the Baltic region . The dynastic conflicts between the Austrian and Spanish Habsburgs and the French king and the Dutch striving for independence took place in western and north-western Europe and northern Italy, while Denmark and Sweden, as possible great powers, fought for supremacy in the Baltic region.

The decisive factor in western and north-western Europe was the conflict between France and Spain , which in turn arose from the dynastic conflict between the Habsburgs and French kings. Spain was a major European power with possessions in southern Italy , the Po Valley and the Netherlands . The scattered Spanish bases meant that there could hardly be a war in western and north-western Europe that did not affect Spanish interests. France, on the other hand, was confronted with Spanish countries in the south, north and south-east, which led to the French “encirclement complex”. Because of their many violent clashes, France and Spain rearmed their armies. In addition to the financial difficulties, Spain also had to fight the uprising in the Netherlands from 1566 , which, however, ended de facto in 1609 with the independence of the United Netherlands and an armistice limited to twelve years.

The conflict in Western Europe could have escalated into a major European war in the Jülich-Klevian succession dispute , when the Duke of Jülich-Kleve-Berg died and the heirs made their claims, including Elector Johann Sigismund of Brandenburg and Count Palatine Wolfgang Wilhelm von Neuburg . The war gained international significance through the intervention of Henry IV of France , who supported the princes of the Protestant Union and in return demanded their help in a war against Spain. The murder of Henry IV in 1610 ended the French involvement in the Lower Rhine for the time being.

In northern Italy there was, in addition to many small principalities, the Duchy of Milan, which was ruled directly by the Spaniards . Neighboring powers of European rank were the Pope and the Republic of Venice , with the Curia in Rome being ruled by French, Spanish and imperial friendly cardinals, while Venice's interests lay more in the Mediterranean and the Adriatic coast than in Italy. The most influential forces in northern Italy were Spain and France, the latter trying to weaken Spanish power and gain supremacy in the region. Both powers tried to win over the local princes with their envoys. The Dukes of Savoy experienced this particularly clearly , as the duchy had a strategically important location: with the Alpine passes and fortresses of Savoy, the important supply route of the Spanish troops to the Netherlands could be controlled.

The three main actors in the wars in the Baltic Sea region were Poland , Sweden and Denmark . Poland and Sweden were temporarily in personal union of Sigismund III. ruled, which prevented the spread of Protestantism in Poland, which was therefore attributed to the allies of Habsburg during the Thirty Years' War. In 1599 he was deposed as King of Sweden due to a revolt of the nobility. As a result, the Lutheran faith established itself in Sweden and a long-term war between Poland and Sweden broke out. The first campaigns of the new Swedish King Charles IX. were initially unsuccessful and encouraged the Swedish rival Christian IV of Denmark to attack. Denmark was less populous than Sweden or Poland, but through the possession of Norway and southern Sweden in sole control of the Øresund , which it posted high tariff income. Charles IX von Sweden, on the other hand, founded Gothenburg in 1603 in the hope of being able to collect part of the customs income from the Oresund. When Christian IV began the Kalmark War in 1611 , Charles IX expected. hence the attack on Gothenburg, instead the Danish army marched surprisingly on Kalmar and took the city. Charles IX died in 1611. and his son Gustav II. Adolf had to pay a high price for peace with Denmark: Kalmar, Northern Norway and Ösel fell to Denmark, plus war contributions amounting to one million Reichsmarks. In order to be able to pay this sum, Gustavus Adolphus borrowed from the United Netherlands. These war debts weighed heavily on Sweden and weakened its foreign policy position. Denmark, on the other hand, had become a Baltic power through the war and Christian IV therefore considered himself a great general on the one hand and believed that he had enough money for further wars on the other.

Denominational contrasts

After the first phase of the Reformation , which divided Germany confessionally, the Catholic and Protestant rulers first tried to find a constitutional order that was acceptable to both sides and a balance of power between the denominations in the empire. In the Augsburg Religious Peace of September 25, 1555, they finally agreed on the Jus reformandi , the Reformation law (later summarized as cuius regio, eius religio , Latin for: whose territory, whose religion; "rule determines the creed"). As a result, the sovereigns had the right to determine the denomination of the resident population. At the same time, the Jus emigrandi , the right to emigrate, was introduced, which made it possible for people of another denomination to emigrate. However, the right of the free imperial cities to reformation remained unclear , because the Augsburg Religious Peace did not stipulate how they should change their confession. Since then, the Catholic and Lutheran creeds have been recognized as having equal rights, but not the Reformed creed .

Also included was the Reservatum ecclesiasticum ( Latin for: "spiritual reservation"), which guaranteed that the properties of the Catholic Church from 1555 should remain Catholic. Should a Catholic bishop convert, he would lose his bishopric and a new bishop would be elected. This regulation also secured the majority in the electoral college , in which four Catholic and three Protestant electors faced each other. The ecclesiastical reservation was only tolerated by the Protestant princes because the Declaratio Ferdinandea ( Latin for: "Ferdinandean declaration") assured that already Reformed cities and estates in ecclesiastical territories would not be forcibly converted or forced to emigrate.

Aggravation of the conflict situation and deterioration of the political order in the Reich

Although the regulations the Peace of Augsburg prevented for 60 years the outbreak of a major religious war , but there were disputes over its interpretation, and a confrontational attitude of a new generation of rulers was the political order in exacerbating the conflict situation and decay. However, because of the opposing parties' lack of military potential, the conflicts were largely non-violent for a long time .

One of the effects of the Augsburg Religious Peace was what is now known as “ denominationalization ”. The sovereigns tried to create religious uniformity and to shield the population from different religious influences. The Protestant princes feared a split in the Protestant movement, which might lose its protection through the Augsburg religious peace and used their position as emergency bishops to discipline the clergy and the population in the sense of their denomination ( social discipline ). As a result, there was bureaucratisation and centralization, the territorial state was strengthened.

In the decades after the Peace of Augsburg, peace in the empire came more and more into danger, when the rulers, theologians and jurists who had experienced the Schmalkaldic War resigned and their successors in office advocated a more radical policy and the consequences of an escalation of the conflict did not noticed. This radicalization was shown, among other things, in the handling of the “spiritual reservation”, because while Emperor Maximilian II still issued “feudal indulges” to Protestant nobles with Catholic bishops (provisionally enfeoffed them so that they could remain politically active, although they were not correct due to a lack of papal confirmation Were bishops), his successor Rudolf II ended this practice. As a result, the Protestant administrators were no longer entitled to vote at the Reichstag without lending or indulgence .

This became problematic in 1588 when the Reichstag was supposed to form a visitation deputation. The visitation deputation was a court of appeal: violations of imperial law (such as the confiscation of goods of the Catholic Church by Protestant sovereigns) were tried before the imperial court. The revision was negotiated before the Reich Chamber Court deputation, or visitation deputation for short. This deputation was filled according to schedule, and in 1588 the Archbishop of Magdeburg should have been a member. Since the Lutheran administrator of Magdeburg, Joachim Friedrich von Brandenburg , was not entitled to vote in the Reichstag without indult, he could not participate in the visitation deputation, which was therefore unable to act. Rudolf II therefore postponed the formation of the deputation until the next year, but no agreement could be reached in 1589 either, or in the following years, which is why an important auditing institution no longer functioned.

Because of the increasing number of revision cases, including above all confiscation of monasteries by territorial lords, the competence of the visitation deputation was transferred to the imperial deputation in 1594 . When a Catholic majority emerged in the Reich Deputation in four revision cases in 1600 (monastery secularizations by the free imperial city of Strasbourg , the Margrave of Baden , the Count of Oettingen-Oettingen and the Imperial Knight von Hirschhorn), the Electoral Palatinate , Brandenburg and Braunschweig left the committee and paralyzed the Reichdeputation thereby. The failure of the auditing institutions weakened the Reich Chamber of Commerce; the princes preferred to negotiate their disputes before the Reichshofrat , which was thereby strengthened. Due to its counter-Reformation attitude, the strengthening of the Reichshofrat also meant strengthening the Catholic side in the empire.

Because of the strengthening of the states, the confrontation policy of the new rulers, the paralysis of the Reich Chamber of Commerce as an instance of peaceful conflict resolution in the Reich and the strengthening of the Catholic princes by the Reichshofrat, rival groups of princes formed. As a result and as a reaction to the battle of the cross and the flag in the city of Donauwörth , the Electoral Palatinate withdrew from the Reichstag. As a result, the Reichstag passed on the Turkish tax and the Reichstag, as the most important constitutional body, was inactive.

On May 14, 1608, the Protestant Union was founded under the leadership of the Electoral Palatinate , to which 29 imperial estates soon belonged. The Protestant princes viewed the Union primarily as a protective alliance that had become necessary because all imperial institutions such as the Imperial Court of Justice were blocked as a result of denominational differences and they no longer took the protection of peace in the empire for granted. The Protestant Union only became politically influential through its connection to France, because the Protestant princes wanted to gain respect from the Catholic princes through a military coalition with France. For its part, France tried to make the Union an ally in the fight against Spain. After the death of the French King Henry IV in 1610, a coalition with the Netherlands was sought, but the States General did not want to be drawn into internal imperial conflicts and left it with a defensive alliance concluded in 1613 for 12 years.

As a counterpart to the Protestant Union, Maximilian I of Bavaria founded the Catholic League on July 10, 1609 , which was supposed to secure Catholic power in the empire. The Catholic League was in the better position, but in contrast to the Protestant Union, there was no powerful leadership figure, rather the battles for hierarchy, especially between Maximilian I of Bavaria and the Elector of Mainz, repeatedly hampered the Catholic League.

Course of war

Outbreak of war

The actual trigger for the war was the class uprising in Bohemia of 1618. It has its roots in the dispute over the letter of majesty , which was issued in 1609 by Emperor Rudolf II and which had guaranteed freedom of religion to the Bohemian estates. His brother Matthias , who ruled from 1612, recognized the letter of majesty when he took office, but tried to reverse the concessions made by his predecessor to the Bohemian estates. When Matthias ordered the closure of the Protestant church in Braunau , forbade the practice of Protestant religion altogether, intervened in the administration of the cities and answered a protest note from the Bohemian estates in March 1618 with a ban on assembly by the Bohemian state parliament, they stormed along on May 23, 1618 The Bohemian Chancellery in Prague Castle was armed with swords and pistols . At the end of a heated discussion with the imperial deputies Jaroslav Borsita von Martinic and Wilhelm Slavata , these two and the office secretary Philipp Fabricius were thrown out of the window ( second Prague lintel ). This act was supposed to work spontaneously, but it was planned from the start. Although the three victims survived, the attack on the imperial representatives was also a symbolic attack on the emperor himself and therefore amounted to a declaration of war. The emperor's subsequent punitive action was thus deliberately provoked.

Bohemian-Palatinate War (1618–1623)

Pilsen - Vražda - Sablat - White Mountain - Mingolsheim - Wimpfen - Höchst - Fleurus - Stadtlohn

War in Bohemia

After the revolt, the Bohemian estates in Prague formed a thirty-member directory that was supposed to secure the new power of the nobility. Its main duties were drafting a constitution, electing a new king and providing military defense against the emperor. The first skirmishes in South Bohemia began in the summer of 1618, while both sides sought allies and prepared for a major military strike. The Bohemian rebels could Friedrich V of the Palatinate , the head of the Protestant Union and the Duke of Savoy Charles Emmanuel I win them over. The latter financed the army under Peter Ernst II von Mansfeld in support of Bohemia.

The German Habsburgs, on the other hand, hired the Count of Bucquoy , who marched on Bohemia at the end of August. The campaign to Prague was stopped for the time being by Mansfeld's troops, who conquered Pilsen at the end of November . The imperial family had to retreat to Budweis .

At first it seemed that the uprising of the Bohemian estates would be successful. The Bohemian army under Heinrich Matthias von Thurn initially forced the Moravian estates to join the uprising, then penetrated into the Austrian homeland of the Habsburgs and stood before Vienna on June 6, 1619 . But the Count of Bucquoy succeeded in defeating Mansfeld near Sablat , so that the Directory in Prague had to call Thurn back to defend Bohemia. In the summer of 1619 the Bohemian Confederation was founded; the Bohemian assembly of estates deposed Ferdinand as King of Bohemia on August 19th and elected Frederick V of the Palatinate as the new king on August 24th . At the same time, Ferdinand traveled to Frankfurt am Main to vote , where the Electors unanimously elected him Roman-German Emperor on August 28th .

With the Treaty of Munich of October 8, 1619, Emperor Ferdinand II managed, with great concessions, to persuade the Bavarian Duke Maximilian I to enter the war, but Ferdinand came under pressure in October when Gabriel , Prince of Transylvania , who was allied with Bohemia Bethlen besieged Vienna. However, Bethlen soon withdrew again, fearing that an army recruited by the emperor in Poland might stab him in the back. In the following year, the lack of support for the Protestant insurgents became apparent, as they were increasingly on the defensive. A meeting of all Protestant princes convened by Friedrich in Nuremberg in December 1619 was only attended by members of the Protestant Union, while in March 1620 the emperor was able to bind the Protestant princes who were loyal to the emperor. Electoral Saxony was assured the Lausitz for his support . With the Ulm Treaty , the Catholic League and the Protestant Union concluded a non-aggression agreement , so that Frederick could no longer expect any help. Therefore, in September the League army was able to march into Bohemia via Upper Austria , while Saxon troops occupied Lusatia. Bethlen's soldiers could not stop the enemy either. On November 8, 1620, the battle of the White Mountain broke out near Prague , in which the Bohemian estates were severely defeated by the generals Buquoy and Johann T'Serclaes von Tilly . Friedrich had to flee from Prague via Silesia and Brandenburg to The Hague and looked for allies in northern Germany. Silesia, on the other hand, broke away from the Bohemian Confederation. In January Emperor Ferdinand imposed the imperial ban on Frederick. Most recently, the Danish king Christian IV invited the Protestant dukes of Lüneburg, Lauenburg and Braunschweig, the ambassadors from England, Holland, Sweden, Brandenburg and Pomerania as well as the expelled Winter King to the “Segeberger Convent” in Holstein's Siegesburg between January and March 1621 to decide joint measures against the Catholic Emperor. After unsuccessful deliberations, the Protestant Union finally dissolved itself in April 1621.

After the victory at Prague, the emperor held a criminal court in Bohemia: 27 people were subsequently charged with lese majesty and executed. In order to push back Protestantism in Bohemia, Ferdinand drove 30,000 families and confiscated 650 aristocratic goods as reparations , which he distributed to his Catholic creditors to repay his debts.

War in the Electoral Palatinate

As early as the summer of 1620, the Spanish military leader Ambrosio Spinola , coming from Flanders , conquered the Palatinate on the left bank of the Rhine, but withdrew to Flanders again in the spring of 1621. A garrison of 11,000 soldiers remained in the Palatinate. The remaining Protestant military leaders Christian von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel , known as the “great Halberstädter” , and Ernst von Mansfeld and Margrave Georg Friedrich von Baden-Durlach moved to the Palatinate from different directions in the spring of 1622. In the Palatinate hereditary lands of the “Winter King”, the Protestant troops initially won the battle of Mingolsheim (April 27, 1622). In the following months, however, they suffered heavy defeats because they outnumbered the loyalists, but they failed to unite. The Baden troops were defeated in the Battle of Wimpfen (May 6, 1622), in the Battle of Höchst Christian von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel was defeated by the League Army under Tilly. Christian von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel then entered service with Ernst von Mansfeld in the Netherlands, where the two armies withdrew. On the march they met a Spanish army, over which they were able to win a Pyrrhic victory in the Battle of Fleurus (August 29, 1622) . From the summer of 1622 the Palatinate on the right bank of the Rhine was occupied by league troops and on February 23, 1623 Friedrich V lost the electoral dignity, which was transferred to Maximilian of Bavaria. Christian von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel suffered another devastating defeat at Stadtlohn and from then on his decimated troops were no longer a serious opponent for the imperial family. The Upper Palatinate fell to Bavaria and was catholicized until 1628. Also in 1628 the electoral dignity of the Bavarian dukes became hereditary, as did the possession of the Upper Palatinate. In return, Maximilian Emperor Ferdinand waived the reimbursement of 13 million guilders for war costs. The territorial expansion of Bavaria and the transfer of a Protestant electoral dignity to a Catholic power changed the power structure in the empire profoundly and laid the foundation for the subsequent expansion of the war.

Restart of the Eighty Years War

When the twelve-year armistice between the Netherlands and Spain expired in 1621 , the Dutch War of Independence began again. Spain had used the peacetime to strengthen its military strength so that it could threaten the Netherlands with an army of 60,000 men. In June 1625, after almost a year of siege , the Dutch city of Breda was successfully forced to surrender, but a renewed financial shortage of the Spanish crown hampered further operations by the Flemish army and thus prevented the complete conquest of the Dutch republic.

Danish-Lower Saxon War (1623–1629)

After the Emperor's victory over the Protestant princes in the empire, France again pursued an anti-Habsburg policy from 1624. In addition, the French King Louis XIII. not only an alliance with Savoy and Venice , but also initiated an alliance of the Protestant rulers in Northern Europe against the Habsburg emperor. In 1625 the Hague Alliance was founded between England, the Netherlands and Denmark. The aim was to jointly maintain an army under the leadership of Christian IV of Denmark , with which northern Germany should be secured against the emperor. Christian IV promised that he would only need 30,000 soldiers, the majority of whom were to be paid for by the Lower Saxony Reichskreis , in which Christian, as Duke of Holstein, was a member with voting rights. In doing so, he prevailed against the Swedish King Gustav II Adolf , who demanded 50,000 soldiers. Christian's main motivation for entering the war was to win Verden , Osnabrück and Halberstadt for his son.

Christian immediately recruited an army of 14,000 men and tried at the district council in Lüneburg in March 1625 to move the district estates to finance a further 14,000 mercenaries and to elect him as district bishop . But the estates did not want a war and therefore made it a condition that the new army only serve to defend the district and therefore not be allowed to leave the district area. The Danish king did not abide by the regulation and occupied Verden and Nienburg cities that belonged to the Lower Rhine-Westphalian Empire .

In this threatened situation, the Bohemian nobleman Albrecht von Wallenstein offered the emperor to initially raise an army at his own expense. In May and June 1625 the imperial councils discussed the offer. The main concern was to provoke a new war by raising an army. However, since the majority of the councilors considered an attack by Denmark to be likely and wanted to arm themselves against it, Wallenstein was made duke in the Moravian Nikolsburg in mid-June 1625 . In mid-July he received his patent for the first generalate and the order to raise an army of 24,000 men, which was reinforced by other regiments from other parts of the empire. By the end of the year Wallenstein's army had grown to 50,000 men. Wallenstein moved into his winter quarters in Magdeburg and Halberstadt , thus blocking shipping traffic on the Elbe , while the League army under Tilly camped further in eastern Westphalia and Hesse.

With his ally Ernst von Mansfeld, Christian planned a campaign that was to be directed first against Thuringia and then against southern Germany. Like the Bohemians and Friedrich von der Pfalz before, Christian waited in vain for significant support from other Protestant powers and in the summer of 1626 was confronted not only with the army of the League, but also with Wallenstein's army. On August 27, 1626, the Danes suffered a crushing defeat against Tilly in the Battle of Lutter am Barenberge , which cost them the support of their German allies.

As early as April 25, 1626, Wallenstein had defeated Christian's ally Ernst von Mansfeld in the battle of the Dessau Elbe bridge . Mansfeld then succeeded again in raising an army with which he dodged south. In Hungary he intended to unite his troops with those of Bethlen in order to subsequently attack Vienna. But Wallenstein pursued the mercenary leader and finally forced him to flee. Shortly afterwards, Mansfeld died near Sarajevo. In the summer of 1627, Wallenstein reached northern Germany and the Jutland peninsula in just a few weeks . Only the Danish islands remained unoccupied by the imperial because they did not have ships. In 1629 Denmark signed the Treaty of Lübeck and withdrew from the war.

The Protestant cause in the empire seemed lost. Like Frederick of the Palatinate in 1623, the Dukes of Mecklenburg, allied with Denmark, were now declared deposed. The emperor transferred their sovereignty to Wallenstein in order to settle his debts with him. Also in 1629, Ferdinand II issued the edict of restitution , which provided for the restitution of all spiritual property confiscated from Protestant princes since 1555. The edict simultaneously marked the climax of imperial power in the empire and the turning point of the war, because it rekindled the resistance of the Protestants, which had already broken, and brought them allies who were ultimately no match for the emperor and the league.

Swedish War (1630-1635)

Frankfurt (Oder) - Werben - Breitenfeld - Rain - Wiesloch - Zirndorf - Lützen - Hessisch Oldendorf - Regensburg - Nördlingen

The widely used designation of the relatively short phase of the war as the “Swedish War” chosen here is strictly speaking arbitrary. The Swedish War actually dragged on for about 20 years, counted from the arrival of the Swedes in 1630 until their departure in 1650. This long period was only briefly interrupted for the Swedes after the Battle of Nördlingen in 1634. when the position of the Swedes collapsed for a few months. There were also similar collapses in other warring parties - on the imperial side even several times - without changing the terms used to describe the phases of the war.

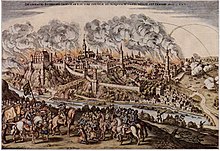

After Denmark, a Baltic power, had left the Thirty Years' War, Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden saw the opportunity to assert his hegemonic claims in north-eastern Europe. On July 6, 1630 he landed on Usedom with an army of 13,000 men and increased his troops to 40,000 men with recruiting. In lengthy negotiations with France, with the Treaty of Bärwalde concluded in January 1631, he secured a basis for financing the planned campaign. Further months of threats and the conquest of Frankfurt an der Oder in April 1631 were necessary to induce Pomerania , Mecklenburg , Brandenburg and Saxony to sign alliances with Sweden. During this time, in May 1631, the city of Magdeburg , which had been besieged for months by the Catholic league troops under Tilly, was conquered. The city was largely destroyed by fire and was almost completely depopulated after more than 20,000 deaths. The event, known as the Magdeburg Wedding , was the greatest massacre of the Thirty Years War and, through hundreds of pamphlets and leaflets, became an effective tool of anti-Catholic propaganda for Protestants.

On September 17, 1631, the Swedish army under Gustav Adolf met the troops of the Catholic League under Tilly in the battle of Breitenfeld north of Leipzig . Tilly was defeated and could no longer stop the advance of the Swedes into southern Germany. He was wounded in the Battle of Rain am Lech (April 14/15, 1632) and retired to Ingolstadt , where he died on April 30 of a serious wound with the word "Regensburg" on his lips. The Swedes tried to take the heavily fortified Ingolstadt, but did not succeed in spite of high losses. After the siege was broken off, a Swedish army group under Horn chased Bavarian troops on their way to Regensburg. Elector Maximilian had the city surprisingly forcibly occupied on April 27, 1632 and thus started the fight for Regensburg . A Swedish attack was expected, because the Protestant imperial city of Regensburg was considered a key fortress on the Danube, which was supposed to protect Vienna and thus Austria from the Swedish attack already feared by Tilly. Instead of attacking Regensburg, the main Swedish army under Gustav Adolf pursued the Bavarian Elector Maximilian, who fled from Ingolstadt to Munich and then on to Salzburg. In mid-May 1632, the barely defended royal seat of Munich was captured by the Swedish army. By paying a high tribute of 300,000 thalers, the city was able to save itself from being plundered. While Gustav Adolf did not tolerate looting in the city of Munich, he had cleared the rural regions of Bavaria for systematic looting by his soldiers on his way to Munich and during his 10-day stay.

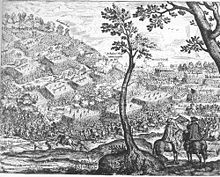

Already at the beginning of 1632, Emperor Ferdinand II had reappointed Wallenstein, who had been dismissed at the Regensburg Electoral Congress in 1630 , as commander-in-chief of the imperial troops, because after the great victory of the Swedes at Breitenfeld, it was to be expected that Swedish and allied Saxon troops would now be in Bohemia and Would threaten Bavaria. Wallenstein had quickly set up a new army in Bohemia, had moved with the army to Nuremberg and had set up a large, strongly fortified and well-supplied camp there . For Gustav Adolf's army in Munich in June 1632, this and the fickleness of his Saxon allies threatened the routes of retreat to the north. Gustav Adolf was forced to retreat from Munich to Nuremberg and put Wallenstein there to fight. However, in the battle of the Alte Veste west of Nuremberg near Zirndorf on September 3, 1632, Wallenstein succeeded in inflicting no defeat on the Swedish army, but so considerable losses that Gustav Adolf was forced to withdraw. When the Wallenstein Army withdrew to winter quarters in Saxony , Gustav Adolf was forced to stand by the allied Saxons. He pursued the withdrawing Wallenstein army, was able to catch up with it near Leipzig at Lützen, but the unexpected attack he had hoped for failed. The Battle of Lützen , which began late on the following day, November 16, 1632, due to fog , initially went well for Gustav Adolf. That changed, however, when the cavalry troops, who had already been released into quarters by Wallenstein, but then ordered back, arrived on the battlefield under Pappenheim , although Pappenheim was killed soon after their arrival. Gustav Adolf also lost his life in a confusing situation. After his death became known, Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar took command of the initially shocked troops on the battlefield and ended the battle successfully for the Swedes.

The death of Gustav Adolf was a grave loss for the Protestants. The Swedish Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna took over the reign over Sweden and also the military command. In order to continue the fight, new army structures and new alliances were required. Oxenstierna concluded the Heilbronner Bund (1633–1634) with the Protestants of the Franconian , Swabian and Rhenish districts . The death of Gustav Adolf also led to considerable restructuring of the Swedish army units and to disputes between the military leaders, under whom Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar was able to achieve a leading position as German imperial prince. He occupied Bamberg in February 1633 and intended to occupy the Upper Palatinate with his new "Frankish Army" and to conquer this key city in the battle for Regensburg in order to advance to Austria from there. Because the troops failed to pay their wages, the plans were delayed and Regensburg was not conquered and occupied until November 1633. Wallenstein had failed to prevent the conquest of Regensburg from Bohemia. This ultimately led to the Bavarian Elector Maximilian and especially Emperor Ferdinand II completely losing confidence in Wallenstein and finding ways to have Wallenstein murdered in Eger on February 25, 1634 .

After Wallenstein's death, the emperor's son, who later became emperor Ferdinand III. , the supreme command of the imperial army. In a joint operation with the Bavarian elector and the Bavarian-led army of the Catholic League under the command of Johann von Aldringen , he was able to recapture this city, which was occupied by the Swedes in November 1633, in July 1634 in the battle for Regensburg . The loss of Regensburg , which was almost prevented by a relief attack by two Swedish armies, which, however, lost a lot of time due to the excessive looting of Landshut , marked the beginning of further military failures for the Swedes. Both Swedish armies had to follow the imperial Bavarian armies that had already withdrawn to Württemberg in forced marches and reached Württemberg exhausted in the rain. There the Swedish generals Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar and Gustaf Horn got into a dispute over the strategic question of how the city of Nördlingen , besieged by the enemy troops , could be liberated. In addition, a Spanish army under the Cardinal Infante had succeeded in penetrating south-west Germany from the south and uniting with the imperial army in front of Nördlingen. There it came to the decisive battle in September 1634 , in which the Protestant Swedish troops under Horn and Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar suffered a devastating defeat, which led to the end of this phase of the war.

After the heavy defeat of the Swedes in 1635, with the exception of the Calvinist Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel, almost all Protestant imperial estates under the leadership of Electoral Saxony broke out of the alliance with Sweden and concluded the Peace of Prague with Emperor Ferdinand II . In the peace treaty, the emperor had to allow the Protestants to suspend the edict of restitution of 1629 for forty years. The Bavarian Elector Maximilian I was also urged to join the alliance and agreed, although he had to integrate his army of the Catholic League into the new Imperial Army. The aim of the imperial princes and the imperial army was to act together and with the support of Spain against France and Sweden as the enemies of the empire. With that the Thirty Years War finally ceased to be a war of denominations. In response to the Peace of Prague, the Protestant Swedes allied themselves with the Catholic French in the Treaty of Compiègne in 1635 in order to also jointly curb the Spanish-imperial power of the Habsburgs.

Swedish-French War (1635-1648)

The widely used designation of the final phase of the war as the "Swedish-French War" reproduced here is slightly misleading. After the accession of Emperor Ferdinand III. in 1637, this phase of the war was marked to a large extent by fighting between imperial-Habsburg and Swedish troops. But that was not the intention of the emperors, because his guiding principle was actually the cooperation with Spain and the common struggle against France, as the "source of all evil".

Wallerfangen - Dömitz - Haselünne - Wittstock - Rheinfelden siege - Rheinfelden battle - Breisach Siege - Witten Weiher - Vlotho - Ochsenfeld - Chemnitz - Bautzen siege - Freiberg sieges - Riebel Dorfer Mountain - Dorsten - Preßnitz - La Marfée - Wolfenbüttel siege - Kempen Heath - Swidnica - Breitenfeld - Klingenthal - Tuttlingen - Freiburg - Jüterbog - Jankau - Herbsthausen - Alerheim - Korneuburg - Totenhöhe - Hohentübingen - Triebl - Zusmarshausen - Wevelinghoven - Dachau - Prague siege

France enters the war

After the heavy defeat in the Battle of Nördlingen , the Swedes found themselves in a military crisis situation. Your negotiations with Protestant military leaders and with Saxons remained unsuccessful because the Swedish needs and demands were not accepted. Instead, the Saxon elector and the emperor concluded the peace in Prague in 1635 , which was then joined by almost all of the Protestant imperial princes and imperial cities that had been allied with Sweden. This strengthened the emperor and the Electorate of Saxony in the conviction that with the Prague peace treaty they had laid the basis for ending the conflict with Sweden.

This hope turned out to be an illusion, because now France, as the previous financial supporter of Sweden, had to fear that the war could end to the advantage of the Habsburg emperor. France, which had previously only been indirectly involved in the war through a proxy war, decided to become active with its own troops. First, on May 19, 1635, France declared war on Spain. In March 1635, Spanish troops conquered the city of Trier, which had been occupied by French troops since 1632 , and captured the Elector von Sötern . France's demanded release of the ally elector was refused, and the elector remained in custody until April 1645.

France declared war on the Habsburg Emperor in Vienna on September 18 and only shortly before a planned preventive strike by the Emperor. The declaration of war had only indirect but serious consequences for the emperor. So far, French financial contributions to the Swedes and Spanish contributions to the emperor had roughly balanced each other out. Now, however, as an official participant in the war, Spain was faced with difficult challenges. This inevitably had a negative effect on the financial contributions from Spain to the emperor, while France was not additionally financially challenged.

Before France entered the war, the French army had 72 regiments of infantry . In the year the war began, the number increased to 135 regiments, reached 174 regiments in 1636 and peaked in 1647 with 202 regiments. After an army reform in 1635, each line regiment numbered 1,060 men. In 1635 the French infantry numbered about 130,000 men, in 1636 there were about 155,000 men and in 1647 about 100,000 men. At the start of the war, the French army was considered to be in poor condition and consisted of soldiers who were inexperienced in relation to the imperial and Swedish soldiers who had been battle-tested in the war.

Stabilization of Sweden

In the interplay of France and Sweden, operational boundaries were made on the theater of war in the Holy Roman Empire. France took over the southern Germany operational zone , which had been abandoned by Sweden . This also included the takeover of fortified places and entrenchments on the Upper Rhine from the Swedes. The Swedes withdrew completely to northern Germany on the coast of the Baltic Sea, to Mecklenburg and the Elbe region. The supplies coming from Sweden by ship across the Baltic Sea were secured there. From there, Saxony and Bohemia could be threatened, because Brandenburg was a militarily weak enemy.

Since Sweden no longer supported Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar , he took up his own alliance negotiations with Richelieu. In October 1635 an alliance and cooperation agreement was concluded. The former Swedish Southern Army under the command of Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar was placed under the French High Command and the commander was guaranteed territory in Alsace . Bernhard von Weimar was guaranteed four million French pounds annually as a disposition budget to pay officers and men and to pay for equipment, quarters, horses, ammunition and food. The southern army had a strength of 18,000 men, made up of former mercenaries from the Swedish army (so-called St. Bernard or Weimaraner ) and French mercenaries. The political leadership under Axel Oxenstierna withdrew to Magdeburg from June 6 to September 19, 1635 and the military commander-in-chief Johan Banér also relocated the last Swedish army on German soil to Magdeburg. The contractual basis for this was the Wismar Treaty concluded in March 1636 on the basis of the Compiègne Treaty . After that, Sweden was to relocate the war via Brandenburg and Saxony to the Habsburg hereditary lands in Bohemia and Moravia, and France was to seize the territory of the Austrian Habsburgs on the Rhine.

When French troops tried to conquer the Spanish Netherlands in May 1635 and the southern Rhineland in September 1635, the project failed in the Netherlands due to the relief of lions by the imperial auxiliary corps for the Spaniards under Octavio Piccolomini and on the Rhine by the imperial main army Matthias Gallas . Gallas was able to push the allied armies from France and from Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar to Metz , but the latter was able to hold the positions on the Upper Rhine . After the dissolution of the Heilbronn Confederation , the Saxon Army formally opened war against its former ally Sweden in October 1635 and blocked Magdeburg from November 1635 . The Swedish soldiers became restless and generals also suspected peace negotiations over their heads. After the heavy defeat of the Swedes at Nördlingen , a mutiny in the Swedish army threatened and in August 1635 the Swedish Chancellor Oxenstierna was detained by mutinous groups. He secretly evaded the troops' grasp in September because he feared for his life. In October 1635 the successes of the Swedes under Banér in the battle of Dömitz and then at Kyritz against a Brandenburg army put an end to the danger of a Swedish collapse.

The Swedes are now doing everything in their power to expand their power base, which has shrunk in Pomerania and Mecklenburg . This was possible because the Imperialists initially concentrated on France and left the expulsion of the Swedes from the imperial territory to Electoral Saxony. Imperial and Bavarian troops under Piccolomini and Johann von Werth support the Spanish troops in the southern Netherlands in 1636. Together they invaded northern France from Mons in early July . After conquering La Capelle and advancing along the Oise towards Paris, they turned west in the expected direction of the French army, captured Le Catelet and crossed the Somme from the north in early August . Riots broke out in Paris after the attackers captured the French border fortress of Corbie , just 100 km north of the city, in mid-August . In the collaboration of Richelieu and King Louis XIII. a people's army was formed, which succeeded in averting the threat to Paris.

In the south, Gallas was to advance with another army to France, for which he gathered his troops in northern Alsace. First, however, he had to send equestrian associations to the Spanish Franche-Comté , whose capital Dole was besieged by a French army. The relief was successful and Imperial Lorraine horsemen subsequently devastated the area as far as Dijon . The only possible direction of attack for Gallas' army was Burgundy, as his cavalry was already there. However, the army of Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar at Langres blocked an advance from there in the direction of Paris . In the north, Corbie was recaptured after a siege by the French army in November 1636. The Spaniards under the Cardinal Infante decided too late for a relief, as they saw their operations as completed. The Spanish military leadership was ultimately satisfied with the acquisition of a few French border fortresses, which Piccolomini saw as a missed opportunity. At the same time, the Swedes succeeded in the battle of Wittstock in a victory against an imperial-Electoral Saxon army. This turned out to be so extensive that the imperial troops were needed as reinforcements in the north-east of the empire for the next year. Before that, Gallas tried one last offensive into the interior of France to win winter quarters in enemy territory and devastate less defended areas, but failed at the beginning of November due to bad weather and the bitter defense of the border town of Saint-Jean-de-Losne . Since the Franche-Comté did not grant the imperial quarters any winter quarters, Gallas had to retreat his troops against the intentions of the imperial military leadership again the long way to the Rhine. Barely half of Gallas' army ended up staying there to safeguard the free county, while the rest were emaciated by a long retreat.

After the win at Wittstock, the situation for Sweden had improved significantly. Kurbrandenburg was under Swedish control again and the Brandenburg elector had to flee to Königsberg in Prussia . In the spring of 1637 the Swedes invaded Electoral Saxony under Banér. The siege of Leipzig failed, however, and after the Saxon troops and the main imperial army returned from Burgundy forced Banér to retreat to Pomerania, the Swedes were again locked in their coastal base. The war was now again on the spot and the number of operations decreased. The degree of devastation, however, had risen sharply, because entire regions were already deserted.

Crisis and intermediate high of the Habsburgs

The direct war intervention by the French and their subsidy payments had meant that the Swedish phase of weakness after 1634 was overcome. The emperor died in 1637. His successor Ferdinand III. pressed for a compromise, but the peace of Prague was already history by then. All other peace initiatives such as that of Pope Urban VIII ( Cologne Peace Congress ) or the Hamburg Congress of 1638 had failed. France itself did not want to make peace before restituting the Palatinate , Hesse-Kassel, Braunschweig-Lüneburg and other Protestant imperial estates and receiving war reparations. Ultimately also represented Ferdinand III. the interests of the old church relations, but tried more to reach a consensus among the empire classes.

The direct participation in the war had so far not been very successful for the French themselves, who were just able to avert a catastrophe in the Année de Corbie in 1636 and had lost their bridgeheads on the Rhine ( Philippsburg and Ehrenbreitstein ) to the imperial by 1637. Only the relief in the fight against the Spaniards through Dutch successes such as the conquest of Breda in 1637 and the advances of Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar on the Upper Rhine successfully brought France back into the war. Bernhard's army first defeated the Duke of Lorraine in the north of Franche-Comté in 1637 and then moved to the Upper Rhine. After he was pushed back across the Rhine by Johann von Werth at the end of 1637, his army inflicted several defeats on the imperial troops in the next year. In January 1638 the Weimar army opened a winter campaign on the left bank of the Rhine and took the forest towns of Säckingen and Laufenburg . Then the army besieged the strategically important city of Rheinfelden and, after a first failure on February 28, defeated the Imperial relief army under Savelli and Werth in the battle of Rheinfelden in a second attempt on March 3, which was completely surprised by its return . After taking over the city of Freiburg in April 1638, the Weimar army began the siege of Breisach in May 1638 . The strongly defended imperial fortress of Breisach had to capitulate in December 1638 despite two attempts at relief by the imperial Bavarian armies. A campaign planned for 1639 did not take place because Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar died unexpectedly on July 18, 1639.

In the spring of 1638, Richelieu feared that the Swedish Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna would increasingly want a separate peace and therefore pushed for the Hamburg Treaty to be passed . In it, Sweden and France extended their alliance against the emperor and ruled out a separate peace with him. Another 14,000 Swedish soldiers reached northern Germany. The Banér, which had previously been included in Pomerania, was able to go back on the offensive, while the Imperialists suffered from increasingly poor supplies in the northern German war zone. They received insufficient support against the Swedes from the weak Brandenburg army, and their own reinforcements were diverted to relieve Breisach. When a Palatine army, financed with English funds, penetrated Westphalia, the Commander-in-Chief Gallas had to withdraw his own troops from Pomerania to defend himself. In October 1638, the imperial army under Melchior von Hatzfeldt smashed the Palatinate-Swedish army under Hereditary Prince Karl Ludwig in the battle of Vlotho . In the north-east, however, the inclusion of the Swedes in Pomerania finally failed because the supply and wintering of the imperial in the area was no longer possible. Gallas withdrew his weakened army into the hereditary lands in the winter of 1638, while the Swedes under Johan Banér moved across the emaciated area to Saxony. In April 1639 they defeated a Saxon army near Chemnitz and pushed on to Bohemia as far as the walls of Prague. The enemies of Habsburg in the empire attentively registered how the overwhelming power of the imperial military melted away. Amalie Elisabeth von Hessen-Kassel broke off negotiations to join the Peace of Prague and concluded an alliance with France in the late summer of 1639. The Guelph Dukes of Wolfenbüttel and Lüneburg , who were included in the Peace of Prague , formed an alliance with Sweden.

In 1640 the emperor convened the Regensburg Reichstag and thereby set a trend-setting signal on the long road to peace. The Reichstag returned its forum to the estates opposition. The dominance of the monarchical system was broken. Since a peace agreement was not possible without the involvement of France and Sweden, neither the imperial estates nor the emperor could determine an imperial peace . Militarily, the Swedish successes led to the recall of Gallas as commander-in-chief and to the recall of Piccolomini's auxiliary corps for the Spaniards in the Austrian hereditary lands. With a well-organized winter campaign, Piccolomini succeeded in driving the Swedes out of Bohemia in early 1640. In the spring and summer the Imperial and Swedes faced each other several times without result, but the Imperial succeeded in slowly pushing back their opponents. After the conquest of Höxter at the beginning of October, the imperial commander-in-chief Archduke Leopold Wilhelm suddenly broke off his own campaign. At the end of 1640, Swedish troops operated together with the now French former army of Bernhard, known as the Weimaraner ; together they advanced to Regensburg in January 1641 in one of the typical Swedish lightning campaigns . However, the Allies could not blow up the Reichstag, which was meeting there, because the ice of the frozen Danube broke in time and Bavarian cavalry arrived to protect the city.

After Banér's surprise attack, which took him to the gates of Regensburg, he had to flee from superior imperial and Bavarian troops under Piccolomini and Geleen and could only save his army with heavy losses to Saxony, where he arrived terminally ill in Halberstadt. Banér's imminent death led to the disintegration of the Swedish army. That seemed to open a window for the Swedes to leave the war permanently for the last time. In the summer of 1641 the war between Brandenburg and Sweden ended, which was another major blow to the Prague peace system. In negotiations with the Swedes, the emperor had to take less account of the Brandenburg claims to Pomerania, but the Swedes were granted passage rights in Brandenburg, which the imperialists were not always granted as a matter of course. The main Imperial Army, which continued to operate jointly with the Bavarians, advanced at the same time across the Saale into Halberstadt . From there they moved to Wolfenbüttel to relieve the fortress besieged by Lüneburg troops and the remaining army of Sweden. An attack on the positions of the besiegers failed, but in the end they withdrew unsuccessfully from the fortress. At the same time, Hatzfeldt achieved success with the capture of Dorsten , the main Hessian fortress in Westphalia. After successes against the German allies of the Swedes, the imperial army did not manage to break up the Swedish army, which was successfully reorganized by its new Commander-in-Chief Lennart Torstensson from the end of 1641 and would deliver a momentous counter-attack in the coming year.

First of all, the imperial auxiliary troops for the Spaniards under Lamboy lost the battle near Kempen on the Lower Rhine against Hessen-Kassel and the Weimaraner in early 1642 . The Bavarian army therefore separated from the imperial in order to support Kurköln against the Hessians and the French. Then Torstensson moved with the Swedish army via Silesia to Moravia and conquered Glogau and Olomouc on the way . Imperial troops maneuvered against the Swedish army and eventually pushed them back into Saxony. The Swedes under Torstensson then besieged Leipzig, and the Imperialists presented him in the Second Battle of Breitenfeld . It ended in a debacle almost as bad for the Austrians as the famous first battle of Breitenfeld.

Fighting in the west, Torstensson War, beginning of peace negotiations

From 1643 the warring parties - the Reich, France and Sweden - negotiated a possible peace in Münster and Osnabrück. The negotiations, always accompanied by further struggles to gain advantages, continued for another five years.

The worsening crisis in Spain after the uprisings on the Iberian Peninsula in 1640 and the lost battle of Rocroi against France in 1643 also had an impact on the situation in the empire. Madrid no longer saw itself in a position to financially support the Vienna Hofburg and was largely militarily tied to the Iberian Peninsula. From then on, Vienna could no longer count on Spanish rescue operations if it got into a military emergency in the empire, as happened in 1619, 1620 and 1634. After the death of Bernhard von Weimar, the French did not succeed in making any further progress on the right bank of the Rhine. Only the enormous losses of the Spanish Flanders Army at Rocroi made an invasion of the Spanish into northern France unlikely. This allowed France to operate with larger contingents on the Rhine front. But here Bavaria stood in their way. The Bavarian Army was able to hold its own against the Royal French Army in southern Germany. They had better provisions than the imperial army and, with Franz von Mercy from Lorraine and equestrian general Johann von Werth, they had very capable military commanders. Together with Lorraine and Spanish troops and an imperial corps under Melchior von Hatzfeldt , they managed to almost completely destroy a Franco-Weimaran army in the battle of Tuttlingen . In the meantime France too showed signs of war weariness. There were unrest there due to the war-related increased tax burden. A peace party developed in the closer circle of power in France. Before his death, Richelieu had become an unpopular person because of his war politics. The successor to the French Prime Minister was Jules Mazarin . The French King Louis XIII. died shortly after Richelieu. The Bavarian Imperial Army succeeded in retaking Freiburg in 1644 and inflicting heavy losses on the French under General Turenne in the Battle of Lorettoberg . In return, Condé occupied several cities on the Rhine, including Speyer, Philippsburg, Worms and Mainz.

At the end of 1643, after a renewed penetration into Moravia, the Swedish military surprisingly withdrew to attack Denmark in the Torstensson War. The imperial responded with their own offensive to support the Danes as far as Jutland , which, however, was unsuccessful. The imperial march back from Holstein turned into a catastrophe. Blocked by the Swedish army of Torstensson in Bernburg in the autumn of 1644 , many soldiers deserted. After Gallas was able to break through to Magdeburg with the remaining troops, he was trapped there. After an outbreak with heavy losses, Gallas' troops made their way to Bohemia. A newly formed army under the command of Hatzfeldt opposed the Swedes who had invaded Bohemia on March 6, 1645 in the battle of Jankau , only to be crushed. The remaining imperial troops then withdrew to Prague to protect the Bohemian capital from further attacks by the Swedes. However, the Swedes decided to advance towards Vienna with their approximately 28,000-strong army. In July 1645 Rákóczi led his troops to Moravia to support Torstensson in the siege of Brno . Ferdinand III. recognized the danger of a joint military advance by Torstensson and Rákóczi against Vienna. On December 13, 1645 between Emperor Ferdinand III. and Prince Georg I. Rákóczi of Transylvania concluded the Peace of Linz . With Saxony, however, an ally of the emperor had previously signed the Kötzschenbroda armistice with the Swedes and had left the war. After the defense of the Swedish advance on the Danube and the successful defense of Brno, the Swedes had to withdraw from Lower Austria, where they still maintained Korneuburg until mid-1646 , and were also pushed back from Bohemia.

In the west Turenne had invaded Württemberg in the spring of 1645 and was defeated by Mergentheim 's army on May 5th near Mergentheim-Herbsthausen . In August 1645, however, with the lost battle of Alerheim, a decisive turning point against Bavaria followed, which Mercy and many soldiers lost. The French also suffered heavy losses and initially had to retreat across the Rhine, but in the summer of 1646 an Allied armies of the French and Swedes operating in unity succeeded in invading Bavaria. These took their quarters in Upper Swabia in winter . Elector Maximilian therefore distanced himself from the emperor and concluded the Ulm armistice with France, Sweden and Hesse-Kassel in March 1647 . But just six months later, Bavaria rejoined the imperial family.

The fighting continued on German soil without any major shifts in force or a decisive battle. In May 1648, the last major battle between the French-Swedish and the imperial-Bavarian armies broke out near Augsburg . The Imperial Bavarian troops lost their entourage and their commander Peter Melander von Holzappel in a battle of retreat , but were able to withdraw to Augsburg in good order. Weakened by losses and desertions, the allies had to give up the line of defense on the Lech and retreat to the Inn . This enabled a further devastation of spa Bavaria. A small Swedish army then invaded Bohemia, where in July 1648 they took the Lesser Town in a flash and then besieged the old and new towns together with advancing reinforcements. In the meantime, under the orders of the recalled Piccolomini, the imperial and Bavarians slowly pushed the opposing armies out of Bavaria and achieved a smaller victory in the battle of Dachau . In the south of Bohemia, the imperial relief troops gathered for the besieged Prague. A decisive battle for the fate of the city, in which the conflict had started 30 years earlier, was not to come. Until the conclusion of the "Peace of Westphalia", with which Europe was reorganized territorially among the warring powers, the Swedes did not succeed in conquering. It was not until the beginning of November 1648 that they broke off the siege, shortly before the arrival of the imperial relief army, which had already brought with them the news of the peace treaty.

Westphalian Peace and the Consequences of War

As part of the Hamburg preliminaries , it was finally agreed at the end of 1641 to hold a general peace congress in the cities of Münster (for the Catholics) and Osnabrück (for the Protestant side). Previously, Cologne and later Lübeck and Hamburg had been thought of as congress venues. After the chief negotiator, Count Maximilian von Trauttmansdorff, left Münster in the summer of 1647 after his failed attempt at arbitration, Reichshofrat Isaak Volmar and the imperial ambassador, Count (later Prince) Johann Ludwig von Nassau-Hadamar, finally brought the peace negotiations to a successful conclusion.

In the Peace of Westphalia, in addition to the Catholic and Lutheran denominations , the Reformed denomination was recognized as having equal rights in the empire. Denominational parity was set for the four equal imperial cities of Augsburg , Biberach , Dinkelsbühl and Ravensburg . Extensive regulations related to the religious issues. In doing so, solutions were found that were partly pragmatic and partly also curious. An alternating government of Protestant bishops (from the House of Braunschweig-Lüneburg) and Catholic bishops was created for the bishopric of Osnabrück . The prince-bishopric of Lübeck was retained as the only Protestant prince-bishopric with a seat and vote in the Reichstag in order to provide the Gottorf family with a secondary education . For the Catholic monasteries in the extinct dioceses of Halberstadt and Magdeburg , which fell to Brandenburg from 1680 , special regulations were made.

The new great power Sweden received in 1648 at the expense of Brandenburg Western Pomerania including Stettin with the entire mouth of the Oder, the city of Wismar and its new monastery as well as the Archdiocese of Bremen and the Diocese of Verden as an imperial fief. Denmark, which claimed the so-called Elbe duchies , was passed over.

Spain agreed with the States General on state independence. The Archduchy of Austria ceded the Sundgau to France . Catholic hegemony over the empire was not achieved.

Otherwise, comparatively little changed in the empire: the power system between the emperor and the imperial estates was rebalanced without significantly shifting the balance compared to the situation before the war. Reich policy was not de-denominationalized, only the way in which the denominations were dealt with was regulated anew. France, on the other hand, became the most powerful country in Western Europe. The peace treaties also granted the Swiss Confederation independence from the jurisdiction of the imperial courts (Art. VI IPO = § 61 IPM) and thus de facto recognized its state independence, which, however, is only the de jure determination of a de facto since the end of the Swabian War of 1499 was established circumstance. With the recognition of the independence of the States General, a development that had begun a century earlier and was de facto completed long before that was ratified. With the Burgundian Treaty in 1548 , the Spanish Netherlands had already been partially detached from the imperial union, and the northern part had finally declared itself independent in 1581 .

Questions that remained unanswered, in particular on the issue of troop withdrawal, were clarified in the following months at the peace enforcement congress in Nuremberg. The transfer of soldiers to civilian life was problematic in many places. Some previous mercenaries formed gangs who marauded through the country, while others were used as guards to ward off those gangs. A certain advantage of the failed agreement between France and Spain was that the soldiers were able to find employment in the ongoing war between the two countries. Venetian advertisements for the war for Crete against the Ottomans also offered many mercenaries an opportunity to continue their military service.

Parts of the Holy Roman Empire had been badly devastated. The extent of the decline in the total population in the Reich area from around 16 million previously is not precisely known. The estimates range from 20 to 45%. According to a widespread statement, around 40% of the German rural population fell victim to the war and epidemics. In cities, the loss is estimated to be less than 33%. The distribution of the population decline was very different: the losses were greatest where the armies passed through or camped. In the areas of Mecklenburg, Pomerania, the Palatinate and parts of Thuringia and Württemberg, which were particularly affected by the chaos of war, losses of well over 50% and in some places up to more than 70% of the population occurred. The north-west and south-east of the empire, on the other hand, were hardly affected by depopulation as a result of the war.

The city of Hamburg was one of the winners of the conflict . The goal of gaining recognition of their imperial status was not achieved, but they were able to concentrate large parts of trade with Central Germany on themselves and develop into one of Europe's leading trading and financial centers. For the large Upper German trading metropolises, the war once again accelerated the downturn at the end of the 16th century. By contrast, the residential cities, which were able to direct large consumption flows in their direction, profited from their decline.

Little attention has been paid to the fact that with the independence of the Netherlands and the loss of important coastal regions and Baltic Sea ports to Sweden, practically all of the major estuaries were under foreign influence. The German states had only a few accesses to the high seas and were thus partially excluded from overseas trade. The possibilities of the empire to benefit from the resurgent maritime trade were thereby limited. The economic aftermath of the Thirty Years War such as B. for colonization , which subsequently led to large territorial gains in other European countries, are controversial in research. In any case, Bremen and Hamburg, the most important German port cities, continued to have free access to the North Sea and world trade. Imperial colonial projects such as the Brandenburg-African Compagnie from Pillau and later from Emden , on the other hand, were unsuccessful due to their poor financial base.

France, England, Sweden and the Netherlands were able to develop into nation states after the Thirty Years' War . The flourishing trade in these countries was accompanied by an upswing in the liberal bourgeoisie. What is controversial is what historical and social consequences this had for the Reich and later for Germany.

Financing the war

At the beginning of the 17th century, the early modern states of Europe had neither financial nor administrative structures that would have been efficient enough to support standing armies of the size required by the Thirty Years' War. The financing of the huge mercenary armies plunged all warring parties into constant financial difficulties, especially the German princes, whose territories were soon largely bled out due to the length and intensity of the conflict (see also Kipper and Wipper times ).

The supposed solution was described by the slogan " War feeds war ". The armies collected taxes and contributions in the form of money and payments in kind from the areas they had traversed. In other words, the country in which the fighting was taking place or which was being occupied had to pay for the costs of the war. The generals took care to strain the areas of opposing parties as much as possible. The longer the war lasted, the more this practice grew into arbitrary looting with all the concomitants of robbery and murder. Wallenstein is credited with saying that a large army is easier to finance than a small one, as it can exert greater pressure on the civilian population.

Troops with semi-regular salaries, such as the Wallensteins or Gustav Adolfs, were more disciplined in collecting money and materials - at least in the first years of the war - than the free mercenary troops, who sometimes joined one party or the other depending on the war situation. They included mercenaries from almost every country in Europe.

Reception history

The war in collective memory and in literature

The historian Friedrich Oertel wrote in 1947 about the effects of the Thirty Years War on the German national character: “German characteristics, however, remain the lack of feeling for the 'liberalitas' of people who are sovereign from within and the lack of feeling for 'dignitas'. The aftermath of the Thirty Years' War still weighs tragically on the history of our people and has stopped the process of maturation. When will the shadows finally disappear, will the omitted be made up? "

The Thirty Years' War left many traces in art and everyday life, as in the nursery rhyme Maikäfer fly with its assigned rhyme: Bet, children, bet, / Tomorrow comes the Swede, / Tomorrow comes the ox star / He will teach the children to pray. / Bet, children, bet. According to Bazon Brock, the cockchafer song is symbolic of a collective defeat of the Germans and stuck in the cultural memory.

In his picaresque novel Der adventurliche Simplicissimus , published in 1669, Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen (1625–1676) described the turmoil and atrocities of war and thus created the first important novel in German literature . The mercenary and later mayor of Görzke , Peter Hagendorf , left an eyewitness report in his chronicle.

The experience of never-ending war, hunger, disease and general destruction gave rise to a poetry of hitherto unknown urgency, in which the certainty of death and transience was combined with baroque lust for life. Andreas Gryphius wrote the sonnet " Tears of the Fatherland Anno 1636", which is still one of the most cited anti-war poems to this day. It begins with the verses:

- We are now whole, even more than completely, devastated!

- The cheeky crowd, the raging trumpet

- The sword fat with blood, the thundering cardoon,

- Has consumed all sweat and industry and supplies.

Martin Rinckart , celebrated as a folk hero and savior in need, wrote “ Now thank all God ” and the Leipzig contemporary witness Gregor Ritzsch wrote “I saw the Swedes with eyes; I must have liked it ”.

The Murrmann treatsthe siege of Geiselwind as a legend .

In the 18th century, Friedrich Schiller dealt with the war as a historian and playwright . In 1792 he published a "History of the Thirty Years War". Seven years later he completed his three-part drama Wallenstein .

As time passed, writers increasingly saw the great conflict of the 17th century as a metaphor for the horrors of war in general. For this, the resulting in the early 20th century historical episode novel is The Great War in Germany by Ricarda Huch an example. The best-known example from the middle of the 20th century is Bertolt Brecht's play " Mother Courage and Her Children ", which is set in the Thirty Years' War, but makes it clear that the brutalization and destruction of people through violence is possible anywhere and at any time .

The Term "Thirty Years War"

After the Second World War , various concepts and approaches in historical studies led to the concept of the “Thirty Years War” being fundamentally questioned. In 1947, the historian Sigfrid Heinrich Steinberg opposed its use for the first time in an article for the English journal History . Later, in 1966, in The Thirty Years War and the Conflict for European Hegemony 1600–1660, he came to the conclusion that the term was merely a “product of retrospective imagination”. Accordingly, "neither Pufendorf nor any other contemporary used the expression 'Thirty Years War'."

At first only a few other historians turned against this statement. In the end, however, the German historian Konrad Repgen disproved Steinberg's thesis, initially in a few articles and later in an extensive essay. Using numerous sources, he proved that the term "Thirty Years' War" had already arisen around the time of the Peace of Westphalia. The contemporary witnesses would have stated its duration in years from the beginning of the war; the humanistic scholars were also inspired by the example of ancient writers. Repgen attributed the name to the need of contemporaries to express the completely new experience that the war had represented for them. This interpretation has been largely adopted by other historians.

Johannes Burkhardt nonetheless pointed out that the term, although contemporary, could nevertheless have denoted a construct, since the Thirty Years' War was in reality a multitude of parallel and successive wars. He attributed the name to the fact that the "war compression" had reached such proportions that it was almost impossible for contemporaries to differentiate between the individual conflicts. This assumption was supported by a 1999 study by Geoffrey Mortimer of contemporary diaries. To this day, other historians have followed Steinberg's tradition of viewing the “Thirty Years War” as an afterthought by German historians.

Reception in museums

In Vienna Museum of Military History of the Thirty Years' War is dedicated to a large area. All kinds of armaments are on display this time, such as muskets , matchlock - wheel lock - and flintlock muskets . Figurines of imperial pikemen , musketeers , cuirassiers and arquebusiers show the protective weapons and equipment of the time. Numerous armor , cutting , stabbing and thrusting weapons round off the area of the Thirty Years' War. The work and fate of the generals , such as Albrecht von Wallenstein , is also illustrated. A special exhibit is Wallenstein's handwriting to his Field Marshal Gottfried Heinrich zu Pappenheim on November 15, 1632, which was written on the eve of the Battle of Lützen and which still has extensive traces of blood from Pappenheim to this day, and Wallenstein's letter is still with him the next day when he was fatally wounded in battle. The so-called “Piccolomini series” by the Flemish battle painter Pieter Snayers is particularly impressive . These are twelve large-format battle paintings that were created between 1639 and 1651 and show Octavio Piccolomini's campaigns in Lorraine and France in the last years of the Thirty Years' War.

In Wittstock an der Dosse , in the tower of the Old Bishop's Castle, the Museum of the Thirty Years' War has been located since 1998 , which documents the causes, the course, the immediate results and consequences as well as the aftermath of the war. In Rothenburg ob der Tauber , in the so-called “historical vault with state dungeon”, you can see a smaller exhibition about the overall situation of the city during the war, including weapons, artillery, military equipment and military equipment of the time.

The upper floor of the Zirndorf Municipal Museum is dedicated to the history of Zirndorf during the Thirty Years' War. In 1632, near the Alte Veste , where Commander-in-Chief Albrecht von Wallenstein had set up a camp, there was a warlike encounter with Gustav II Adolf of Sweden . Dioramas and models as well as contemporary descriptions of camp life, the fate of the soldiers and the civilian population illustrate this chapter in Franconian war history.

Historical sources

The Hessian State Archives in Marburg keep a large number of cards related to the Thirty Years' War in the “Wilhelmshöher War Cards” collection. The maps document theaters of war and war events. They also provide insights into the changes in the landscape, cities, roads and paths, etc. The individual maps are fully accessible and can be viewed online as digital copies. The Stausebach local chronicle of the Caspar Prize is also kept there, which describes the course of the war in Hesse from his peasant perspective. The Mainz historian Josef Johannes Schmid brought out a source collection in 2009.

See also

- Timeline for the Thirty Years War

- List of envoys to the Peace of Westphalia

- Little ice age

- Second Thirty Years War

Movies

- The forgotten valley (GB / USA 1971). Directed by James Clavell .

- Christoffel von Grimmelshausen's adventurous simplicity (ZDF, D 1975). Director: Fritz Umgelter .

- The Iron Age - Loving and Killing in the Thirty Years War (ZDF, Arte; D 2018). Directed by Philippe Bérenger, Yury Winterberg. Six-part television documentary.

- The souls in fire (TV film, Germany 2014). Director: Urs Egger.

- Gustav Adolfs Page (D / AUT 1960). Director: Rolf Hansen .

- Wallenstein (ZDF, D 1978). Director: Franz Peter Wirth. Four-part television film based on the biography of Golo Mann .

- The Thirty Years War (1/2) - Diaries of Survival (Documentation Terra X, ZDF, 2018) by Ingo Helm and Volker Schmidt-Sondermann

- The Thirty Years War (2/2) - Devastation and Reconciliation (Documentation Terra X, ZDF, 2018) by Ingo Helm and Volker Schmidt-Sondermann

literature

Overall presentation

- Johannes Arndt : The Thirty Years War 1618–1648. Reclam, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-15-018642-8 .

- Günter Barudio : The German War 1618–1648. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-10-004206-9 .

- Friedemann Needy : Pocket Lexicon Thirty Years' War. Piper, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-492-22668-X .

- Johannes Burkhardt: The Thirty Years War. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1992, ISBN 3-518-11542-1 .

- Axel Gotthard : The Thirty Years War. An introduction. (= UTB. 4555). Böhlau Verlag, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2016, ISBN 978-3-8252-4555-9 .