Albert Einstein

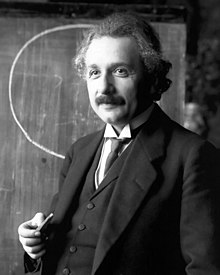

Albert Einstein (March 14, 1879 in Ulm – April 18, 1955 in Princeton, New Jersey ) was a German physicist with Swiss and US citizenship. He is considered one of the most important theoretical physicists in the history of science and the most famous scientist of modern times worldwide . His research into the structure of matter , space and time and the nature of gravitation significantly changed what had previously been validNewtonian worldview.

Einstein's main work, the theory of relativity , made him world famous. In 1905 his work entitled On the electrodynamics of moving bodies was published, the content of which is now referred to as the special theory of relativity . In 1915 he published the general theory of relativity . He also made significant contributions to quantum physics . "For his services to theoretical physics, especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect ," he received the 1921 Nobel Prize , which was presented to him in 1922. Contrary to popular belief, his theoretical work played only an indirect role in the construction of the atomic bomb and the development of nuclear energy .

Albert Einstein is considered the epitome of the researcher and genius . He also used his extraordinary reputation outside of the scientific community in his commitment to international understanding , peace and socialism .

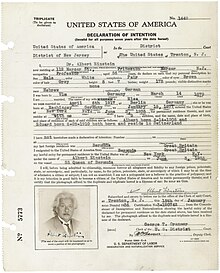

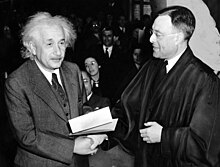

In the course of his life, Einstein was a citizen of several countries: by birth he held Württemberg citizenship . From 1896 to 1901 he was stateless because he did not want to do military service in Germany. From 1901 until his death he was a citizen of Switzerland , in 1911/1912 he was also a citizen of Austria in Austria-Hungary . From 1914 to 1932 Einstein lived in Berlin and, as a citizen of Prussia , was again a citizen of the German Reich . When Hitler seized power in 1933, he finally gave up his German passport and was deprived of his citizenship by the German Reich in 1934 . In addition to his Swiss citizenship , he acquired United States citizenship in 1940 .

Life

childhood and adolescence

ancestors and parental home

The parents , Hermann Einstein and Pauline Einstein , both came from Jewish families that had lived in Swabia for centuries. The maternal grandparents had changed their surname from Dörzbacher to Koch. The paternal grandparents still had traditional Jewish first names , Abraham and Hindel or Helene Einstein. That all changed with Albert Einstein's parents.

His father Hermann Einstein came from the small town of Buchau in Upper Swabia , where there had been a significant Jewish community since the Middle Ages within the territory of the free-world Buchau women's monastery (see also: Einstein family in Bad Buchau ). The first named ancestor of Albert Einstein, a horse and cloth dealer named Baruch Moses Ainstein from the Lake Constance area, was admitted to the community in the 17th century. The names of many of Einstein's relatives can still be found on the tombstones of the Buchau Jewish Cemetery ; including that of the last Jew in the city, Siegbert Einstein, a great-nephew of the physicist who had survived the Theresienstadt concentration camp and was temporarily the second mayor of Buchau.

Hermann Einstein moved to Ulm with his brothers in 1869. In Cannstatt near Stuttgart he married Pauline Koch in 1876 and lived at Bahnhofstraße 20 (B135), where Albert Einstein was born on March 14, 1879. Albert grew up in an assimilated , non - orthodox , middle -class German-Jewish family. Later, shortly after his 50th birthday, Einstein spoke to the Ulmer Abendpost about his hometown as follows:

“The city of birth clings to life as something as unique as coming from one's birth mother. We also owe a part of our character to our birthplace. So I think of Ulm with gratitude, as it combines noble artistic tradition with a simple and healthy nature.”

Albert Einstein kept in touch with his slightly older cousin Lina Einstein, who lived in Ulm. In 1940, at the age of 65, she was forcibly admitted to the Jewish retirement home in Oberstotzingen. Albert Einstein's attempts to get Lina an exit permit to the USA failed. In 1942 Lina Einstein was deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp and murdered in the Treblinka extermination camp in the same year .

Munich and school education until 1894

Shortly after Albert's birth in 1880, the family moved to Munich , where his father and uncle founded a small gas and water installation company in October 1880. Since this was economically satisfactory, they decided in 1885 and with the support of the entire family to set up their own factory for electrical equipment (Elektrotechnische Fabrik J. Einstein & Cie) . His father's company was successful and supplied power plants in Munich-Schwabing, Varese and Susa (Italy). Two and a half years after Albert, his sister Maja (* November 18, 1881 in Munich; † June 25, 1951 in Princeton, New Jersey, USA) was born. What is certain, however, is that the family lived in a building in the backyard of Adlzreiterstrasse 12, which today belongs to the property at Lindwurmstrasse 127 in the Munich district of Isarvorstadt .

Albert Einstein began speaking at the age of three. In 1884 he began playing the violin and received private lessons. The following year he went to elementary school, from 1888 he attended the Luitpold-Gymnasium (after various relocations it was given the name Albert-Einstein-Gymnasium in 1965 and should not be confused with today 's Luitpold-Gymnasium in Munich). At school he was a bright, sometimes even rebellious student, his grades were good to very good, not so good in languages, but outstanding in science. Einstein read popular science books and got an overview of the state of research. Aaron Bernstein 's natural science folk books in particular are considered to have had a significant impact on his interest and future career. This also includes Felix Eberty 's writing The Stars and World History. Thoughts about space, time and eternity, for the new edition of which Einstein wrote a foreword in 1923.

The father's and beloved uncle's company closed and the family moved to Milan in 1894 . Albert, who was fifteen at the time, was supposed to stay at the Luitpold-Gymnasium until he graduated from high school, but was insulted by the director and came into conflict with the school system of the German Empire , which was characterized by discipline and order - but he was open about it. Teachers accused him of rubbing off on classmates with his disrespect. Einstein defiantly decided at the end of 1894 to leave school without a degree and to follow his family to Milan. Another motive was obviously the intention not to have to do military service. If Einstein had stayed in Germany until the age of 17, he would have been called up for military service – a prospect that terrified him.

Switzerland 1895-1914

The way to study: Matura in Aarau

During the spring and summer of 1895 Einstein stayed in Pavia , where his parents lived temporarily, and helped out in the company. He made trips to the Alps and the Apennines and visited his uncle Julius Koch in Genoa . During this time, the 16-year-old Einstein wrote his first scientific work, an essay entitled On the investigation of the state of the ether in the magnetic field, and sent it to his uncle Caesar Koch (1854-1941), who lived in Belgium , for his approval. The work was never published as a scientific paper in a journal and remained in the form of a discussion paper.

Einstein did not follow his father's wish to study electrical engineering . Instead, he followed the advice of a family friend and applied for a place at the Swiss Federal Polytechnic School in Zurich, now ETH Zurich . Since he did not yet have a high school diploma or Swiss Matura , he had to take an entrance exam in October 1895, which he - as the youngest participant at the age of 16 - did not pass. He mastered the scientific part with flying colors and failed due to a lack of knowledge of French .

On the mediation of the mechanical engineering professor Albin Herzog , who was convinced by him , he then attended the trade school at the liberally run Aargau canton school in Switzerland to catch up on the Matura there. During this time in Aarau he stayed with the Winteler family . He moved there in October 1895 for a year; soon a liaison began with Marie Winteler, who was two years older than him. At the beginning of 1896, at the request of his father, Einstein was released from Württemberg and thus also from German citizenship . He registered as not belonging to any religious community. He remained stateless for the next five years.

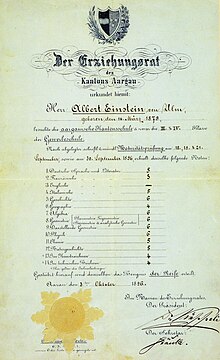

On Einstein's certificate of the "Maturitätsprüfung" issued on October 3, 1896, there were five times the best possible school grade , in Switzerland a six. The worst grade was a three in French. The rumor that Einstein was a bad student in general is false: it goes back to Einstein's first biographer, who confused the Swiss grading system with the German one.

Studies at the Polytechnic in Zurich

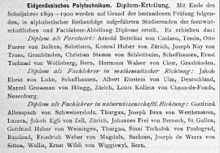

After Einstein had caught up on his Matura at the Kantonsschule Aarau, he began his studies at the school for subject teachers of the Swiss Federal Polytechnic in Zurich (today ETH Zurich ) at the beginning of the academic year 1896 .

Einstein was not just interested in learning formal knowledge ; rather, theoretical-physical thought projects stimulated him. With his idiosyncrasy, he often rubbed people the wrong way. The abstract mathematical education was a thorn in his side, he considered it a hindrance for the problem-oriented physicist. In the lectures, the teaching professor noticed him mainly because of his absence. For the exams, he relied on the notes of his fellow students. This ignorance not only blocked his career opportunities at his university, he regretted it at the latest when he developed the mathematically highly demanding general theory of relativity . His fellow student Marcel Grossmann was of great help to him later on.

Einstein left the university in 1900 with a diploma as a specialist teacher in mathematics , which also included physics. He completed his diploma thesis in physics with Heinrich Friedrich Weber . However, he did not succeed in getting a job as an assistant at the polytechnic after his studies.

From private tutor to patent office in Bern

His applications for assistant positions at the polytechnic and other universities were rejected. He worked as a tutor in Winterthur , Schaffhausen and finally in Bern . In 1901 his application for Swiss citizenship was granted. On June 16, 1902, on the recommendation of his friend Marcel Grossmann, Einstein received a permanent job: as a third-class technical expert at the Swiss Patent Office in Bern.

During his probationary period at the Patent Office began his regular meetings with philosophy student Maurice Solovine and mathematics student Conrad Habicht , dubbed the Olympia Academy , ending in 1904.

Family situation

During his studies, Einstein had met his fellow student and later wife, Mileva Marić from Novi Sad . After the death of his father at the end of 1902, the two married in Bern on January 6, 1903 – against the will of the families. With Marić, Einstein had a daughter and two sons, Hans Albert (1904–1973) and Eduard (1910–1965). The daughter Lieserl was born in 1902 before the marriage to Marić's parents in Novi Sad and either died early or was given to Belgrade for adoption in 1903. Despite an intensive search, the fate of the child is unknown. The existence of their daughter was kept secret even from their friends. Only in 1987, through the publication of Einstein's letters to Marić from 1897 to 1903, did it become known that their daughter had been born before their marriage. The marriage ended in divorce in 1919.

From October 1903 to May 1905, Einstein and Marić lived in the old town of Bern at Kramgasse 49, today 's Einsteinhaus Bern , which houses a museum.

From first publications to the famous formula E = mc² (1905)

In 1905, at the age of 26, Einstein published five of his most important works:

- On March 17, 1905 he finished his work on the photoelectric effect , which he subsequently published as On a heuristic point of view concerning the production and transformation of light .

- On April 30, 1905, he completed his dissertation A New Determination of Molecular Dimensions, with which he submitted his doctoral application to Professors Alfred Kleiner and Heinrich Burkhardt at the University of Zurich on July 20 . He chose the University of Zurich because there was no need for the rigorosum (oral examination) due to an agreement with the polytechnic where Einstein had studied. In his dissertation he calculated the size of sugar molecules in solution and from that a value for Avogadro's constant . It is related to his work on Brownian motion, which was published in the same year, and supported the atomic hypothesis, which at the time was still being disputed by leading physicists ( Wilhelm Ostwald , Ernst Mach ). The work was accepted relatively quickly by Burkhardt and Kleiner (the doctoral procedure was completed in July). However, Paul Drude , the editor of the Annalen der Physik to whom Einstein had sent the work, was not satisfied with the value found for Avogadro's constant and requested corrections, which Einstein also provided. This led to a six-month delay in publication and Einstein was therefore only formally awarded his doctorate on January 15, 1906. Four years later (1909), when Jean Perrin's experiments became known, Einstein approached Perrin with a request for experimental verification, and at the same time Ludwig Hopf , whom Einstein had asked for verification of his dissertation, found an error in his dissertation, affecting the result had falsified. Einstein then sent a correction to the Annals in 1911.

- On May 11, 1905 followed his publication on Brownian motion : About the motion of particles suspended in liquids at rest, which is required by the molecular-kinetic theory of heat.

- On June 30, 1905, Einstein submitted his treatise On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies . Shortly thereafter, Einstein delivered his addendum Does the inertia of a body depend on its energy content? The latter implicitly contains for the first time what is probably the world's most famous formula, E = mc² (energy equals mass times the speed of light squared, equivalence of mass and energy ). Both works together are now referred to as the special theory of relativity .

The year 1905 was therefore an extremely fruitful year, one also speaks of the annus mirabilis (miracle year). Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker later wrote:

"1905 an explosion of genius. Four publications on different topics, each of which is, as we say today, worthy of a Nobel Prize: the special theory of relativity , the light quantum hypothesis , the confirmation of the molecular structure of matter by 'Brownian motion', the quantum theoretical explanation of the specific heat of solid bodies.

The steps to the new theory of gravitation

When Einstein started the long journey from the special to the general theory of relativity in 1907, he was still a largely unknown employee in the patent office in Bern. At the end of the path, in 1915, he was already a highly respected professor in Berlin, who, as Max Planck later said, could only be “measured by the achievements of Johannes Kepler and Isaac Newton”.

The path to the general theory of relativity began in 1907 on the one hand with the flash of inspiration that Einstein described as "the happiest thought of my life" and on the other hand with a limitation of his previous work on relativity that was of a fundamental nature. The latter was the insight that the speed of light under the influence of gravity is not a constant, so that special relativity could only be valid under the condition that gravity did not exist, as Einstein repeated in a 1911 paper: "The theory of relativity has shown that the inertial mass of a body increases with the energy content of the same. (...) The so satisfying result of the theory of relativity, according to which the law of the conservation of mass merges into the law of the conservation of energy, could not be maintained.”

The flash of inspiration, on the other hand, concerned the equivalence between inertial and gravitational mass, i.e. the correspondence between the constant acceleration of a reference system and gravity: "I was sitting in my chair in the Bern patent office when the following thought suddenly came to me: 'When a person is in free fall , then she does not feel her own weight'. I was amazed. This simple thought made a deep impression on me. He pushed me towards a theory of gravity.”

However, it was still more than three years before the first writing in which this flash of inspiration led to a more detailed physical formulation, because "Einstein did not comment on questions of gravitation from December 1907 to June 1911 (...)", according to his friend and Biographer Abraham Pais .

In 1908, however, there was a groundbreaking innovation, which Einstein was initially skeptical about and which he even dismissed as "superfluous erudition": the mathematical formulation of space -time by his former teacher Hermann Minkowski , whose authorship of this revolutionary conception was later expressly recognized by Einstein and was appreciated.

In the Minkowski space , the relative relationship between the quantities of space and time in the special theory of relativity can be represented as a rotation by setting an imaginary unit of time. It was not until 1912 that Einstein was convinced of the advantages of the Minkowski space.

Some of the most important essays of the later general theory of relativity at a glance:

- On the principle of relativity and the conclusions drawn from it.

- On the influence of gravity on the propagation of light. Still according to Huygens' principle, Einstein only determined a deviation of the light rays from fixed stars in the vicinity of the sun of 0.83 arc seconds, the value calculated according to the field equations of 1915 was 1.7 arc seconds.

- Draft of a generalized theory of relativity and a theory of gravitation. I. Physical part of Albert Einstein. II. Mathematical part by Marcel Grossmann.

- Nordstrom's theory of gravitation from the point of view of the general differential calculus. With AD Fokker . A reaction to Gunnar Nordstrom 's alternative theory of gravitation and a "publication of considerable interest in the history of general relativity because it represents Einstein's first treatment of the theory of gravitation in which general covariance is strictly valid".

- On the general theory of relativity. November 4, 1915.

Since the still conventional definition of distance in flat (non-curved) Minkowski space does not hold equally well in curved space-time, it had to be replaced there by a more abstract expression, just as a geometry was required to extend Gauss's theory of areas to curved spaces could be expanded in four dimensions. Einstein's mathematical knowledge at the time was not sufficient for this, so in 1912 he turned to his former fellow student Marcel Grossmann , who was now a professor of mathematics in Zurich. Einstein "asked him to look in the library to see if there was a suitable theory for dealing with such questions. Grossmann came the next day (...) and said that such a geometry actually existed, namely Riemannian geometry.”

As a result, Grossmann not only sought out the works of Riemann , but also those of Christoffel , Ricci and his student Levi-Civita , some of whom were already doing research on the absolute differential calculus in curved spaces, the formulation of the Christoffel symbols for tensor analysis and the covariant derivation in the 19th, and partly only in the 20th century, had developed the mathematical tools that now proved to be indispensable for the formulation of the general theory of relativity.

However, it took another three years to formulate the idea of a gravitational field in which the metric of the four-dimensional, curved space-time continuum and the factors of energy and momentum are mutually dependent, which Einstein succeeded on November 4, 1915 .

professorship

Einstein's application for habilitation in 1907 at the University of Bern was initially rejected because he had not submitted his habilitation thesis, but he was only successful the following year. In 1909 he was appointed lecturer in theoretical physics at the University of Zurich , soon becoming an associate professor. In January 1911, as Minister of Education Stürgkh announced, he was appointed full professor of theoretical physics at the German University of Prague by Emperor Franz Joseph I. This made him an Austrian citizen. In October 1912 he returned to Zurich to do research and teach at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology ; he therefore returned to his place of study as a professor. Einstein considered Zurich his hometown and Switzerland the country he was drawn to throughout his life.

Berlin years 1914-1932

Professional encounters and family cuts

In 1913, Max Planck succeeded in persuading Einstein to become a full-time salaried member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin, where he arrived in April 1914. His wife accompanied him with the children, but soon returned to Zurich because of private differences. Einstein received the license to teach at the University of Berlin , but without any obligation to do so. Freed from all teaching activities, Einstein found time and peace in Berlin to complete his great work, the general theory of relativity. He was able to publish them in 1916, along with a paper on the Einstein-de-Haas effect . On October 1, 1917 he became director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics and remained in this position until 1933. From 1923 to 1933 Einstein was also a member of the Senate of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society .

Between 1917 and 1920 his cousin Elsa Löwenthal (née Einstein; 1876–1936) cared for the ailing Einstein; a romantic relationship developed. In view of this, Einstein divorced Mileva in early 1919 and married Elsa a little later. She brought two daughters into the marriage. That time was associated with further cuts: the political situation after the end of the First World War prevented contact with his sons in Switzerland. At the same time, his mother fell seriously ill in early 1919 and died the following year. In addition, Kurt Blumenfeld managed to get Einstein interested in Zionism just now .

The Berlin years were also characterized by close contact with Max Wertheimer , the founder of the Gestalt theory . There was a fruitful exchange between the two scientists. For example, Einstein wrote an introduction to Wertheimer's Essays on Truth, Freedom, Democracy , and Ethics . Increasingly, he also began to open up to political issues (see the section on political commitment ).

Along with Leopold Infeld , he was one of the frequent visitors to the family of Antonie "Toni" Mendel († 1956), Bruno Mendel 's aunt and mother-in-law , with whom he was a close friend. He had met them in the early 1920s through joint membership in the pacifist New Fatherland League .

Experimental confirmation of the predicted light deflection (1919)

During the solar eclipse of May 29, 1919 , observations by Arthur Eddington confirmed that the deflection of a star's light by the Sun 's gravitational field was closer to that predicted by general relativity than by Newton's corpuscle theory . Joseph John Thomson , President of the Royal Society , commented on the finding as follows:

"This result is one of the greatest achievements of human thought."

The experimental confirmation of Einstein's prediction, which seemed odd at the time, made headlines around the world. From then on, the sudden notoriety ensured that Einstein's lectures were extremely popular. Everyone wanted to see the famous scientist in person . The Einstein Tower in Potsdam was built between 1920 and 1924 on the initiative of Erwin Freundlich , a long-time collaborator . Since then it has been used for astronomical observations, not least for the purpose of further testing Einstein's theory.

Awarded the Nobel Prize (1922)

The 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics was only awarded on November 9, 1922: to Albert Einstein “for his services to theoretical physics, especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect ”. Einstein had embarked from Marseille on October 7th for a lecture tour to Japan, arriving there on November 17th, and was therefore unable to attend the award ceremony in Stockholm on December 10th, 1922. There the envoy of the German Reich Rudolf Nadolny took it upon himself to "receive his prize from the hands of H.M. the king" and at the evening banquet in the Grand Hôtel Stockholm to say words of thanks "also on his behalf". Einstein left the prize money to Mileva Marić and their sons , as was already stipulated in the divorce certificate.

Construction of the "Einstein House"

On the occasion of Einstein's 50th birthday in 1929, the city of Berlin felt the need to present its famous citizen with an appropriate gift. Lord Mayor Gustav Böß suggested that he bequeath a house. The press picked up the story. Over time, however, the discussion escalated into open controversy. Einstein and Elsa, meanwhile looking for a suitable piece of land at Waldstraße 7 in the village of Caputh near Potsdam , decided without further ado to accept the gift and financed what is now called the Einstein House out of their own pockets. Architect Konrad Wachsmann was commissioned to build the two-storey wooden house on the slope above the lake. It was the starting point for many sailing boat tours during the summer months up to 1932. This boat (a birthday present from friends) was a " 20er dinghy cruiser " named Tümmler, which was confiscated by the Nazis in 1933 along with Einstein's remaining belongings .

The confrontation with Niels Bohr

In 1930, at the sixth Solvay Conference , Albert Einstein surprisingly confronted Niels Bohr with his thought experiment of the photon balance , with which he wanted to prove the incompleteness of quantum theory . Just one day later, however, Bohr, together with Pauli and Heisenberg , was able to refute Einstein using considerations from the general theory of relativity .

Princeton 1932-1955

Traveling and German expatriation

Einstein took advantage of his increasing fame for a number of trips: With the permission of the Prussian Ministry of Education, he gave lectures all over the world. In 1921 he made his first trip to the USA, staying there for several months. He has received numerous honorary doctorates , including those from Princeton University , where he later taught. He soon made plans to spend half of the year in Princeton , New Jersey , and the other half in Berlin . In Berlin, he had increasingly become the subject of political debates because of his pacifist attitude. In December 1932 he traveled again to Pasadena (California) . Einstein traveled to Europe in March/April 1933 after the Nazi regime came to power (January 30, 1933); he returned his passport to the German embassy in Brussels.

On March 28, 1933, he wrote (with regret) to the Prussian Academy of Sciences, to which he had belonged for 19 years, and acknowledged the suggestions and human relationships there. In doing so, he forestalled an expulsion that loomed after the publication of a pacifist statement not intended for the press. At the same time, two other signatories to the urgent appeal against the Nazi regime's takeover of power ( Heinrich Mann and Käthe Kollwitz ) had already been forced to leave the academy. On March 20, Einstein's house in Caputh was searched, and in April his city apartment at Haberlandstrasse 5 in Berlin (today's new building, No. 8). On April 4, 1933, Einstein applied for expatriation (release from the Prussian state association). A four-page letter dated March 28, 1933 to Einstein's sister Maja, in which Einstein and his wife communicated their desire for expatriation, was auctioned off in 2018. The application was rejected; he was stripped of his citizenship by being expatriated (on March 24, 1934) and placed on the German Reich's second expatriation list.

On April 8, 1933, the Bavarian Academy of Sciences contacted him and asked him for an explanation regarding his attitude towards the Bavarian Academy, of which he had been accepted as a corresponding member in 1927. Einstein replied from the Belgian resort of De Haan on April 21 that the reasons for his departure from the Prussian Academy did not in and of themselves necessitate a severing of his ties with the Bavarian Academy. However, he wishes to be removed from the list of members. The German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina had already deleted Einstein as a member in early 1933 with a pencil entry in their register books. On May 10, 1933, the propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels proclaimed : “Jewish intellectualism is dead” and, as part of the public burning of “un-German writings” , had writings by Einstein also symbolically burned. Einstein also found that his name was on an assassination list with a $ 5,000 bounty on his head . A German magazine put his name on a list of enemies of the German nation with the comment: "not yet hanged".

Search for the world formula

In 1933 Einstein became a member of the Institute for Advanced Study , a private research institute that had recently been established near Princeton University . From August 1935 until his death, Einstein lived at 112 Mercer Street in Princeton. At that time, the city formed a microcosm of modern research. Einstein soon set about finding a unified field theory that would unify his field theory of gravitation (the general theory of relativity) with that of electromagnetism . Until his death, he tried in vain to find a universal formula - which no other researcher has succeeded in doing to this day.

Private situation in exile

Einstein undertook his last trip abroad outside the USA after moving there in 1935 to the Bermuda Islands, which belong to Great Britain, a forced stay for formal reasons, since he was not yet a US citizen at the time.

Einstein's wife Elsa died in 1936. In 1939 his sister Maja came to Princeton, but without her husband Paul, who had not received an entry permit. She lived with her brother until her death in 1951.

In 1938, together with Thomas Mann , he helped the writer Hermann Broch , who had been briefly imprisoned in previously “annexed” Austria, also to emigrate to the United States. Both remained friends in exile. Like him, Einstein also helped his Caputh architect Konrad Wachsmann and numerous other threatened Jewish artists and scientists to leave Germany and enter the USA by providing letters of recommendation and expert opinions.

On December 15, 1938, he resigned from the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei in Rome after it had previously expelled all 27 Jewish Italian members.

On October 1, 1940, Einstein received US citizenship . He retained his Swiss citizenship ( citizenship of Zurich) for the rest of his life.

Einstein's signature on the atomic bomb

The discovery of nuclear fission in December 1938 by Otto Hahn and Fritz Straßmann in Berlin brought about the realization of a nuclear threat in the scientific community. In August 1939, just before the start of World War II , Einstein signed a letter written by Leó Szilárd to American President Franklin D. Roosevelt , warning of the danger of a "bomb of a new type" that Germany might be developing and might even soon possess. In the face of secret service reports about corresponding German efforts, the appeal was heard, and additional research funds were made available: the Manhattan project with the declared goal of developing an atomic bomb was launched.

In his memoirs, Einstein argues that he was too easily persuaded of the need to sign this letter. On November 16, 1954, he said to his friend Linus Pauling :

“I made one great mistake in my life — when I signed the letter to President Roosevelt recommending that atom bombs be made; but there was some justification — the danger that the Germans would make them.”

“I made a grave mistake in my life—when I signed the letter to President Roosevelt recommending atomic bombs; but there was some justification for it – the danger that the Germans would build some.”

However, Einstein was completely uninvolved in the work. Although he was consulted by Vannevar Bush in December 1941 on an isotope separation problem, he was classified as a security risk by the FBI and Washington officials, partly because of his undisguised communist sympathies, and by the observed by US secret services. He was therefore not allowed to be initiated into the technical details of the Manhattan project and was even not allowed to officially receive knowledge of the existence of the top-secret project. However, he was interested in working with the US military and, from May 1943, advised the US Navy on explosives and torpedoes. As a contribution to the war effort, he donated his original 1905 manuscript on special relativity, which was auctioned in Kansas City in February 1944 for $6.5 million, which was invested in US war bonds.

In 1945, Leó Szilárd approached him again, this time to prevent the use of nuclear weapons after Germany's surrender , and Einstein wrote a letter of introduction for Szilárd to the President, which was ineffective after Roosevelt's death, so that Szilárd could express his concerns to him. After the atomic bomb was dropped, Einstein, who initially remained silent, was pressed to comment after his 1939 letter to Roosevelt was exposed by the Smyth Report . In an interview with a journalist from the New York Times in September 1945, he spoke out in favor of a world government to prevent future wars created the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists , but continued its commitment to international arms control even after it ended in 1948. In March 1947, in a Newsweek interview, he judged his own involvement in the initiation of the Manhattan Project that he would not have done so if he had known that the Germans had made little progress in their atomic bomb project, and that the development would have happened without it it would have happened.

retirement

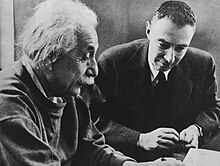

After the war, the image of the old, carelessly dressed professor at Princeton stuck in the public mind. He was frequently asked for his opinions and was visited by high-ranking guests of state such as Jawaharlal Nehru . Even after his retirement in 1946, he continued to work on his unified field theory with assistants at the Institute for Advanced Study. His last years were marred by the death of his sister Maja in 1951 and other friends. In May 1953, in a letter published in the New York Times , he opposed the McCarthy committees and called for them to remain silent. In 1954 he supported Robert Oppenheimer in his safety hearings.

attitude towards Germany

The extermination of the Jews carried out by the Germans during the National Socialist era was the reason for Einstein to maintain until the end of his life the general rejection he had expressed in a letter to Arnold Sommerfeld in December 1945: "After the Germans murdered my Jewish brothers in Europe, I don't want to have anything to do with Germans anymore, not even with a relatively harmless academy." Referring to Sommerfeld and a few others, he added: "It's different with the few individuals who have remained steadfast in the realm of possibility."

Even years after the war, he saw no pronounced feelings of remorse or guilt in Germany and continued to avoid any involvement with the local public institutions. He brusquely rejected Otto Hahn's request to become a member of the Max Planck Society, as did Sommerfeld's request to reinstate him in the Bavarian Academy of Sciences , and Theodor Heuss ' request for the Pour le Mérite Order . He also didn't want his books to be published in Germany in the future. He reacted with incomprehension to the news that his friend Max Born wanted to move back to Germany. However, he did not generally transfer his dislike of Germany to individuals or colleagues, especially not if they, like Sommerfeld, Max Planck and Max von Laue , had kept their distance from the National Socialists.

concern for peace

Despite his ailments, shortly before his death he found the strength he needed to stand up for his vision of world peace . On April 11, 1955, together with ten other well-known scientists, he signed the so-called Russell-Einstein Manifesto to sensitize people to disarmament . Einstein's final notes concern a speech he intended to give on the anniversary of Israeli independence. He was still working on the draft on April 13, 1955 together with the Israeli consul. Einstein collapsed that afternoon and was taken to Princeton Hospital two days later.

death

Einstein died in Princeton on April 18, 1955 at the age of 76 from internal bleeding caused by a ruptured aortic aneurysm . Einstein rejected the (at the time experimental) surgical treatment with the words:

“I want to go when I want. It is tasteless to prolong life artificially. I have done my share; it is time to go. I will do it elegantly."

"I'll go if I want to. It is distasteful to artificially prolong life. I have done my part; it's time to leave. I will do so gracefully.”

Einstein had suffered from the aneurysm for years. It was discovered and stabilized during a laparotomy in late 1948 after Einstein kept complaining of abdominal pain. Due to health problems, he had hardly left Princeton since the late 1940s. Princeton Hospital night nurse Alberta Rozsel was with Einstein when he died. She reported that shortly before his death he mumbled something in German. Pathologist Thomas Harvey took Albert Einstein's brain and eyes after the autopsy . His intention was primarily to preserve the brain for posterity for further investigation of its possibly unique structure. The surviving relatives gave him their consent retrospectively. Most of the brain is now preserved in the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Chicago , and the eyes in New York . In accordance with Einstein's wishes, his body was cremated and the ashes scattered at an undisclosed location.

Scientific discoveries and inventions

physics

theory of relativity

Albert Einstein founded the physical theory of relativity , which he (after important preliminary work by Hendrik Antoon Lorentz and Henri Poincaré ) published in 1905 as the special theory of relativity and for the first time in 1915 as the general theory of relativity . Einstein's works led to a revolution in physics; the special and general theories of relativity are still among the cornerstones of modern physics. In order to simplify the formulation, he introduced Einstein's summation convention in 1916 , which allows tensor products to be written more compactly.

subject of the Nobel Prize

Einstein was nominated for the Nobel Prize with increasing frequency from 1910 , especially from 1919 after the public sensation of the correct prediction of the deflection of light by gravitation. However, this met with persistent resistance in the Nobel Prize Committee, which also meant that the prize for 1921 was not awarded on schedule, but only a year later together with the prize for 1922. Many members of the Nobel Prize Committee were more inclined towards experimental physics than theoretical physics and suspected the theoretical developments on the quantum nature of light and on the two theories of relativity as too speculative. While Einstein's law of the photoelectric effect had now been verified by measurements, the observation reported by Arthur Stanley Eddington in 1919 during solar eclipse observations that the general theory of relativity predicted the deflection of light from stars near the sun ( gravitational lensing effect ) was further doubted due to a lack of measurement accuracy. Allvar Gullstrand in particular , who also believed to have found various errors in Einstein's theories, prevented Einstein's nomination as late as 1921, despite the strongest international support.

Einstein received the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics, but only a year later and neither for one of his theories of relativity nor for the light quantum hypothesis , with which he had found the law of the photoelectric effect, but only for the discovery of this law. For his Nobel Prize speech, he was ordered not to comment on the theory of relativity. Because of a stay in Japan, Einstein did not take part in the official state ceremony in December 1922, but accepted the award on July 11, 1923 at the 17th Nordic Naturalist Meeting (17:e Skandinaviska Naturforskarmötet) in Gothenburg and held it - to the delight of the Swedish king who was present and another thousand listeners - his speech entitled Basic ideas and problems of the theory of relativity. Anti-Semitic physicists from Germany, including Philipp Lenard , the 1905 Nobel Prize winner, had previously protested in vain.

quantum physics

Einstein's relationship to another pillar of modern physics, quantum physics, is remarkable : on the one hand, because some of his work, such as the explanation of the photoelectric effect, formed the basis for it; on the other hand, because he later rejected many ideas and interpretations of quantum mechanics . A famous discussion connects Einstein with the physicist Niels Bohr . The subject was the different interpretation of the new quantum theory that Heisenberg , Schrödinger and Dirac developed from 1925 onwards. Einstein was particularly critical of Bohr's concept of complementarity .

Einstein believed that the random elements of quantum theory would later be proven not truly random. This attitude caused him, for the first time in his argument with Max Born , to make the famous statement that the old man (or Lord God) does not throw dice:

“Quantum mechanics is very formidable. But an inner voice tells me that this is not yet the real Jacob. The theory provides a lot, but it hardly brings us any closer to the mystery of the old. In any case, I am convinced that the old man does not play dice.”

He supported his considerations with various thought experiments , including the much-discussed Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen experiment and the photon balance . In the discourse, however, Bohr and his followers were mostly victorious; Even from today's point of view, the experimental evidence speaks against Einstein's point of view.

laser

In 1916 he postulated the stimulated emission of light. This quantum-mechanical process is the physical basis of the laser , which was only invented in 1960 – i.e. after his death. Along with the transistor , the laser is one of the most important technical inventions of the 20th century that go back to quantum physics.

Bose-Einstein condensation

In 1924, together with Satyendranath Bose , he predicted a quantum-mechanical, but nevertheless macroscopic state of matter that should occur at extremely low temperatures. The phase transition , later known as the Bose-Einstein condensation , was observed in the laboratory for the first time in 1995. In August 2005, a 16-page manuscript by Einstein dealing with his last major discovery, the Bose-Einstein condensation, was discovered at Leiden University .

Unified Field Theory

In his late years Einstein dealt with the question of a unified field theory of all natural forces based on his general theory of relativity; an undertaking that was not crowned with success and is still unresolved today.

Einstein is often cited as one of those who rejected and wanted to abolish a hypothetical ether ; however, this was only the case to a limited extent, as becomes clear in one of his speeches, delivered on May 5, 1920 at the Reich University in Leiden :

“In summary, we can say: according to the general theory of relativity, space is endowed with physical qualities; in this sense an ether exists. According to the general theory of relativity, space without ether is unthinkable; because in such a space there would not only be no propagation of light, but also no possibility of the existence of scales and clocks, and therefore no spatio-temporal distances in the sense of physics. However, this ether must not be thought to be endowed with the property characteristic of ponderable media, to consist of parts that can be traced through time; the concept of movement must not be applied to it.”

In the sense of this summary, Einstein only allows a gravitational ether that is independent of electrodynamics, but not the electromagnetic ether of the 19th century with its necessary states of motion, which - as in 1905 - are still expressly excluded. This fact is also clearly expressed in the often quoted speech of 1920, a little before the above summary.

“If we consider the gravitational field and the electromagnetic field from the point of view of the ether hypothesis, there is a remarkable difference in principle between the two. No space and no part of space without gravitational potentials; for these give it its metric properties, without which it cannot be thought at all. The existence of the gravitational field is directly linked to the existence of space. On the other hand, a part of space can very well be imagined without an electromagnetic field.”

See also:

- Unified Field Theory

- Ether (physics) , especially gravitational ether

- Einstein sum convention

- Einstein coefficients

technology

Einstein is world famous as a theoretical physicist. However, a comprehensive picture of his scientific personality is missing one facet if one does not take into account his achievements as an experimental physicist and engineer.

Einstein-de-Haas effect

In 1915, Einstein conducted a difficult experiment with Wander Johannes de Haas . Through what is now known as the Einstein-de-Haas effect, he indirectly determined the gyromagnetic ratio of the electron . Since the spin was not yet known at that time, it was believed that ferromagnetism was based on the orbit of the electrons around the atomic nucleus (ampere molecular currents), which would have meant a Landé factor of 1. The difficulty of the experiment introduced larger statistical errors; however, a series of measurements came very close to the predicted value and was considered and published by Einstein and de Haas as experimental evidence of the model. However, later experiments with higher accuracy show that a Landé factor of about 2 follows for the spin of the electron from the Dirac equation. This shows that the ferromagnetism cannot arise from the orbital angular momentum of the electrons.

gyrocompass

Einstein contributed to the technology of the gyro compass with his inventions of the electrodynamic bearing and the electrodynamic drive for the gyroscope. Einstein had acquired relevant specialist knowledge when he was appointed as an expert in a patent dispute between Hermann Anschütz-Kaempfe and Elmer Ambrose Sperry in 1914 . Mechanical gyros are still built today using Einstein's patented technology.

coolant pump

It is reported that Einstein and his colleague Leó Szilárd were motivated by a tragic accident involving the toxic refrigerants that were common at the time to research safe refrigerators. One of the patents filed by Einstein and Szilárd was for an electrodynamic pump for a conductive refrigerant. In the United States, both were granted US Patent Number 1,781,541 on November 11, 1930 for the refrigerator. Although Einstein was able to sell several of his patents, including to AEG and Electrolux , his refrigerators were never built because the refrigerant Freon was introduced in 1929, making Einstein's patents suddenly obsolete. Einstein's invention survived at one point: The pumps for the coolant in fast breeder reactors , namely for liquid sodium, are still designed according to Einstein's principle.

cat hump wings

Presumably inspired by Ludwig Hopf , Einstein dealt with the flow properties of aircraft wings at the beginning of the First World War and designed a wing profile around 1916 in which he wanted to reduce the air resistance by dispensing with the angle of attack . In connection with this, he published the work Elementary Theory of Water Waves and Flight in August 1916. The airline in Berlin-Johannisthal implemented Einstein's design suggestions, and the wings were called cat 's hump wings because of their less than elegant shape. A test flight then showed, however, that the construction was unusable due to its poor flight characteristics. Test pilot Paul G. Ehrhardt had a hard time landing the plane, describing it as a "pregnant duck." Einstein himself was later, probably also with regard to possible military applications, glad that his suggestions had proved useless and was ashamed of his "foolishness from those days".

Political commitment

positioning

At the age of nineteen, during the era of Wilhelminism at the end of the 19th century , Einstein felt such disgust for militarism and the dependence on authority in the society of the German Empire that he renounced his German citizenship.

The beginning of the First World War caused an intensive preoccupation with political problems. Einstein joined the Bund Neues Vaterland (later the German League for Human Rights ) and supported its demands for an early, just peace without territorial claims and the creation of an international organization that would prevent future wars. In 1914 he wrote to his colleague Paul Ehrenfest :

“The international catastrophe weighs heavily on me as an international person. It is difficult to grasp, when experiencing this "great time," that one belongs to this crazy, depraved species that ascribes free will to itself. If only there were an island of the benevolent and level-headed! I also wanted to be an ardent patriot.”

In 1918, Albert Einstein was one of the signatories to the call to found the left-liberal German Democratic Party (DDP). Later, however, he no longer appeared publicly for this party, instead he increasingly approached a humanistic socialist body of thought. During the course of the Weimar Republic , he continued to be involved in the German League for Human Rights, in which he campaigned for political prisoners. In this context he also worked temporarily for the communist -dominated Red Aid .

In 1932, as a signatory of the Urgent Appeal , he joined Heinrich Mann , Ernst Toller , Käthe Kollwitz , Arnold Zweig and others in favor of an anti-fascist left- wing alliance of SPD , KPD and trade unions in order to still prevent the downfall of the Weimar Republic and the threatening rule of National Socialism .

pacifism

After Einstein had attracted attention during the First World War due to his anti-war position, he was a member of the Commission for Intellectual Cooperation at the then League of Nations from 1922 , at the suggestion of which he later discussed the question Why War? entered into an exchange of letters with Sigmund Freud in September 1932, which was published in 1933. In general, he repeatedly resorted to writing letters in order to achieve an effect:

In May 1931, for example, he and Heinrich Mann drew attention to the murder of the Croatian intellectual Milan Šufflay in an open letter to the New York Times . In 1935 he took part in the (successful) international campaign for the Nobel Peace Prize to be awarded to Carl von Ossietzky , who was in a concentration camp ; In 1953 he wrote a public letter calling for the defense of civil rights to the McCarthy Committee .

At the beginning of March 1933, during a stay in the USA, he made a statement to the League for Combating Anti-Semitism , which he said was not intended for the press, and which drew a great deal of attention in the international press. In it he wrote:

"As long as I have an opportunity, I will only stay in a country where political freedom, tolerance and equality of all citizens before the law prevail. Political freedom includes the freedom of oral and written expression of political convictions, tolerance respect for any conviction of an individual. These conditions are currently not met in Germany. ... I hope that healthy conditions will soon set in in Germany and that in future the great men like Kant and Goethe will not only be celebrated there from time to time, but that the principles they taught will also prevail in public life and in general consciousness .”

At the same time he modified his pacifist stance:

“Up until 1933, I advocated conscientious objection to military service. But when fascism arose, I realized that this position was unsustainable lest the power of the world fall into the hands of mankind's worst enemies. Against organized power there is only organized power; I see no other remedy, much as I regret it.”

The letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt that preceded the development of the atomic bomb also sprang from this attitude:

"I felt we had to avoid the possibility of Germany having sole possession of this weapon under Hitler. That was the real danger of that time.”

Accordingly, after the defeat of Nazi Germany , he became involved in a variety of ways for international arms control and cooperation, in the sense of the title of a speech he gave at a Nobel memorial dinner in New York in 1945 : The war is won, but peace is not. He created an Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists and proposed the formation of a world government .

Einstein was also opposed to violence towards animals and sympathized with the idea of vegetarianism . Presumably, however, he only became a vegetarian towards the end of his life.

Zionism

When he was appointed to Charles University in Prague (1911), Einstein initially described himself as “non-denominational”. Only after pressure from the Austro-Hungarian administration to declare his faith did he admit that he was a member of Judaism . Later, however, Einstein, affected by the situation of Eastern European Jewish refugees after World War I, showed increased commitment to a state of Israel. His participation in a provisional committee to prepare a Jewish congress in Germany is documented in 1918. At that time the German Reich was already experiencing an increasing permeation of anti-Semitism .

He broadly supported Zionist ideals, but never joined any Zionist organization. After initially leaving the Jewish religious community as a youth, he became a member of the Jewish community in Berlin in 1924, although he did not do so for religious reasons, but to demonstrate his solidarity with Judaism. His name is also strongly associated with the Hebrew University in Jerusalem . One of the purposes of his first trip to the USA was to collect donations for such a university. In 1923 he traveled to what was then Palestine to lay the foundation stone - during this trip he was also awarded the first honorary citizenship of the city of Tel Aviv . In 1925 he was appointed a member of the university's board of directors. Finally, in his will, Einstein decreed that his written estate be transferred to the Hebrew University.

Einstein's relationship to Judaism was apparently not religious in nature . As he wrote in 1946:

“Although I'm something of a Jewish saint, it's been so long since I've been to a synagogue that I fear God won't recognize me. But if he did, it would probably be worse.”

When Menachem Begin visited New York shortly after the independence of the State of Israel to collect donations for his newly founded Cherut party, Albert Einstein was one of the signatories to a letter to the editor of the New York Times on December 4, 1948 , which, in sharp language, of the Cherut party (which merged into today's Likud in 1973).

In 1952, after the death of Chaim Weizmann , Einstein was offered the position of second president of the newly founded State of Israel , which he turned down.

In December 1982, the Hebrew University in Jerusalem received Albert Einstein's private archive. The material dates from 1901 to 1955 and comprises 50,000 pages and up to 1982 around 33 unpublished manuscripts.

socialism

In 1949 Einstein wrote his little-known essay Why Socialism? (“Why Socialism ?”), in which he explained his political views: Although he admits that he is not an expert in the field of economics, he considers it permissible to state:

"[...] we should not assume that experts are the only ones entitled to speak out on issues affecting the organization of society."

He emphasized the dependence of the individual on society and the opportunity to shape society:

"Memory, the capacity to try new things, and the ability to communicate orally have made developments possible for humans that were not dictated by biological realities. Such developments manifest themselves in traditions, institutions and organizations, in literature, in scientific and technical achievements, in artistic works. This explains why people can in a certain sense influence their own lives and that conscious thinking and willing play a role in this process.”

He criticized capitalism for not doing justice to society's needs for the economy:

“Production is for profit – not for need. There is no provision that all those who are able and willing to work can always find work.”

This has an impact right into the education system:

“Unlimited competition leads to a huge waste of labor and to that crippling of the social consciousness of individuals that I mentioned earlier. I consider this paralysis of the individual to be the greatest evil of capitalism. Our whole education system suffers. The student is drummed into excessive competition and is trained to see rapacious success as a preparation for his future career [...] I am convinced that there is only one way to eliminate these grave evils, and that is to establish the socialist economy, combined with an on Education that meets social goals: The work equipment becomes the property of society and is used by it in a planned economy."

But he also demanded that the desired socialism must respect the rights of the individual :

“A planned economy as such can go hand in hand with the total enslavement of the individual. Socialism requires the solution of some extremely difficult socio-political problems: How is it possible to prevent a bureaucracy from becoming all-powerful and excessive in the face of far-reaching centralization of political and economic forces? How can the rights of the individual be protected and thereby ensure a democratic counterweight to bureaucracy? […] Clarity about the goals and problems of socialism is of the utmost importance in our time of transition. Unfortunately, in the current state of society, free discussion of these things is hampered by a powerful taboo.”

In doing so, he also raised questions that were relevant in the Eastern bloc ( Stalinism ). Unlike his other ideals , such a discussion went unnoticed in the West during the Cold War , which is why the text found little circulation outside of socialist circles. In the US, Einstein was under surveillance by the FBI because of his political views. Agents not only tapped his phone and checked his mail, they also went through his trash. The FBI file containing so-called "incriminating information" against Einstein totals 1,800 pages.

Einstein was a member of the Society of Friends of the New Russia , which propagated friendship between Germany and the Soviet Union. He was also honorary president of the Soviet-German Society "Culture and Technology" .

abortion, homosexuality and sex education

In 1929, the Neue Generation , organ of the German Federation for Maternity Protection , quoted a letter from Einstein dated September 6, 1929 to the World League for Sexual Reform, Institute for Sexual Science , Berlin:

"I do not have such rich human experience as to be entitled to speak publicly on these difficult social questions. I only have the feeling of a certain security in the following point: Abortion up to a certain stage of pregnancy should be allowed at the request of the woman. Homosexuality should go unpunished except for the necessary protection of young people. No secrecy regarding sex education .”

Later, Einstein was among the supporters or sympathizers of a committee for self-incrimination against Section 218 , see Abortion#First Half of the 20th Century .

attitude to religion

Einstein comes from a Jewish family. When he renounced German citizenship in 1896, however, his father noted, probably at his request, "no religious affiliation", which he repeated several times over the next two decades.

Up to the 21st century, there are different interpretations of Einstein's attitude towards religion, as he often expressed contradictory statements, including the aphorism : "Science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind." Einstein's privately owned letter to the esotericist Erich Gutkind , written on January 3, 1954. In this Einstein refers to his non-religious attitude. In doing so, he clearly distances himself from the biblical idea of a personal God, which he describes as “childlike superstition”:

"For me the word God is nothing but an expression and product of human weaknesses, the Bible a collection of venerable but rather primitive legends."

"To me, the unadulterated Jewish religion, like all other religions, is an incarnation of primitive superstition. And the Jewish people, to which I am happy to belong and with whose mentality I am deeply attached, has no different quality for me than all other peoples. As far as my experience goes, it is no better than other human groupings, albeit secured against the worst excesses by lack of power. Other than that, I don't see anything 'chosen' about him.”

In another letter he writes in 1954:

“Of course, what you read about my religious beliefs was a lie, a lie that is systematically repeated. I do not believe in a personal God and I have never denied this but have stated it clearly. If there is anything in me that could be called religious, it is an unbounded admiration for the structure of the world, as far as our science can reveal.”

In one of a total of 27 personal letters from Einstein that were auctioned by the Profiles in History auction house in Los Angeles in June 2015 , when history teacher Guy Raner was asked about his beliefs in 1949, Einstein replied that he had repeatedly said that the idea of a personal God in his opinion is a childlike. One might call him an agnostic , but he does not share the combative spirit of atheism, preferring a humble attitude corresponding to the weakness of our intellectual understanding of nature and our own existence:

“I have repeatedly said that in my opinion the idea of a personal God is a childlike one, […]. You may call me an agnostic, but I do not share the crusading spirit of the professional atheist … I prefer an attitude of humility corresponding to the weakness of our intellectual understanding of nature and of our own being.”

“I have said several times that I think the idea of a personal God is a child's, […]. You can call me an agnostic, but I don't share the fighting spirit of a professional atheist... I prefer a humble attitude towards the weakness of our intellectual understanding of nature and our essence.”

awards

- 1909 honorary doctorate from the University of Geneva .

- 1914: Full member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences . In 1933 Einstein announced his resignation from the Academy.

- 1915: Corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen (external member from 1923). In 1933 Einstein was expelled.

- 1917: Honorary award from the Peter Wilhelm Müller Foundation in the mathematics category, shared with David Hilbert .

- 1919: On November 12, Einstein was awarded an honorary doctorate (Dr. med. hc) at the suggestion of Moritz Schlick to mark the 500th anniversary of the University of Rostock ; the only German honorary doctorate that Einstein received.

- 1920: Member of the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and the Royal Netherlands Academy of Sciences

- 1920: Elected to the Order Pour le Mérite as its youngest member. When he emigrated in 1933, Einstein returned his medal to the Chancellor of the Order, Max Planck (1858–1947); he refused to re-enter in 1951.

- 1921: Barnard Medal .

- 1921: Honorary Doctorate from the University of Manchester

- 1921: Foreign member of the Roman Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei . Einstein resigned from membership in 1938 because of fascist racial legislation. In 1945 it was reactivated.

- 1921: Honorary doctorate from Princeton University

- 1922: On November 9, the award of the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics was announced "for his services to theoretical physics , particularly for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect ."

- 1922: Corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences (1926 honorary member)

- 1923: first honorary citizen of Tel Aviv .

- 1923: Honorary doctorate from the University of Madrid and member of the Real Academia de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales in Madrid.

- 1924: Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences .

- 1924: Honorary Member of the London Mathematical Society .

- 1925 Copley Medal from the Royal Society.

- 1926: Gold Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society .

- 1927: Appointment as corresponding member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences . Einstein terminated membership in 1933 and declined re-admission in 1946.

- 1927: Honorary Member of the Royal Society of Edinburgh .

- 1929 Honorary Doctorate from the Sorbonne .

- 1930: On November 7, Einstein was awarded an honorary doctorate (Dr. hc) from ETH Zurich to mark the 75th anniversary of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology .

- 1930: Member of the American Philosophical Society .

- 1931: Jules Janssen Prize of the French Astronomical Society.

- 1932: Honorary Doctorate from Oxford University

- 1932: Member of the Leopoldina .

- 1933: Member ( associé étranger ) of the Académie des sciences .

- 1934 honorary doctorate from Yeshiva College in New York.

- 1935 Benjamin Franklin Medal (Franklin Institute)

- 1935: Honorary doctorate from Harvard University

- 1942: Member of the National Academy of Sciences .

- In 1952, at the age of 73, Einstein was offered the office of President of Israel .

- 1979: On February 26, the GDR issued a commemorative coin for Einstein's 100th birthday.

- In 1984, Jürgen Goertz erected the Einstein fountain in Ulm.

- In 1999, 100 leading physicists voted Einstein the greatest physicist of all time.

- In 1999, Time magazine named him Man of the Century .

- 2005: 100 years after the publication of Einstein's four fundamental papers in the Annals of Physics in 1905, the year 2005 was proclaimed the World Year of Physics , also known as the Einstein Year. From April to September 2005, the so-called Einstein Mile was set up on Berlin 's Unter den Linden boulevard .

- The chemical element einsteinium , the auxiliary unit Einstein , a lunar crater , an asteroid and the space freighter ATV-4 were named after Albert Einstein .

- His bust was placed in the Walhalla near Regensburg at the suggestion of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences .

- The following awards bear his name: Albert Einstein Peace Prize , Albert Einstein Medal , Albert Einstein Award , Einstein Prize .

- One of the first new Intercity Express trains ( ICE 4 ) was named after Albert Einstein .

Depiction of Einstein in the visual arts (selection in alphabetical order of the artists)

- Hermann Hubacher : Bronze bust of Einstein in ETH Zurich , created in 1957

- Herbert Nitzschke : Portrait of Prof. Albert Einstein (chalk drawing, 1953)

- Arthur Sasse's photograph of Albert Einstein - sticking his tongue out at him - during his 72nd birthday in 1951 became a media icon .

- Hanfried Schulz : Albert Einstein (woodcut, c. 1957)

- Emil Stumpp : Albert Einstein (chalk lithograph, 1929)

Others

Impact on Family Members

On August 3, 1944, near Rignano sull'Arno , the wife and two daughters of Einstein's cousin Robert were shot by uniformed Germans, presumably because of their relationship to Albert Einstein. As a result of what is known as the Einstein case , Robert Einstein committed suicide on their wedding day in 1945 . On February 23, 2011, the State Criminal Police Office of Baden-Württemberg tried to solve the triple murder by broadcasting it on the program Aktenzeichen XY ... unsolved . Dozens of tips were received after the broadcast, but these proved to be ineffective. The proceedings against a suspected perpetrator living in Kaufbeuren, which were later initiated on the basis of a statement by the niece who was present at the time, were discontinued due to his inability to stand trial , without his possible involvement in the crime being publicly clarified. The deeds are not cleared up to this day.

Lasting memories of Albert Einstein

In December 2014, Princeton University (where Einstein once taught) put around 5,000 texts and documents online. The documents date from the first 44 years of his life.

A carriage of the Ulm tram bears his name. The Ulm Einstein Marathon is also named after him.

A plant genus Einsteinia from the Rubiaceae family was also named by Adolpho Ducke in 1934.

In the Einstein Tower in Potsdam, designed by Erich Mendelsohn and now a listed building , the validity of the theory of relativity was to be experimentally confirmed.

In Bern, within the Historical Museum , there is an Einstein Museum, an Einstein House, an Einstein Terrace and an Einstein Street, in other cities there are Einstein Streets such as in Radebeul and Albert Einstein Schools in numerous places.

Statues have been erected in his honor in various cities , such as the Albert Einstein statue in Washington, DC

handwriting

Albert Einstein's handwriting was digitized as a font in an art project by Elizabeth Waterhouse and the typographer Harald Geisler . This makes it possible to write texts in Einstein's handwriting on the computer or smartphone. The project was presented on the crowdfunding platform Kickstarter in 2015 in cooperation with the Albert Einstein Archive Jerusalem and was funded by 2334 backers. The font contains several variants of each letter, each based on templates from Einstein's manuscripts, these different letters are automatically adjusted as you write, creating a natural typeface.

The Albert Einstein font was used to recreate the correspondence between Einstein and Sigmund Freud . 2017 on the 85th anniversary of the exchange of letters, which was published in 1933 under the title Why War? was published, Harald Geisler presented the project on Kickstarter in cooperation with the Sigmund Freud Museum and the Albert Einstein Archive . Supporters received the letters in the author's handwriting or could send them to politicians of their choice. The letters were sent from the same place and day as in 1932, Einstein's letter on July 30 from Caputh and Freud's reply in September from his apartment in Vienna.

writings

work edition

- The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein. (CPAE) Editors John Stachel , Martin J. Klein , David C. Cassidy , Robert Schulmann , Ann M. Hentschel, Tilman Sauer , Anne J. Kox and others, overall direction Diana L. Kormos-Buchwald . Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1987-. Complete edition arranged chronologically; 16 volumes have been published by July 2021, including manuscripts and (in separate volumes) selected letters. The total volume is estimated at around 30 volumes.

Scientific essays

- A New Determination of Molecular Dimensions . Buchdruckerei KJ Wyss, Bern 1905, doi : 10.3929/ethz-a-000565688 (inaugural dissertation at the University of Zurich).

- On a heuristic point of view concerning the production and transformation of light . In: Annals of Physics . tape 322 ( Vol 17 of the 4th series), 1905, p. 132–148 , doi : 10.1002/andp.200590004 ( mpg.de ).

- On the movement of particles suspended in liquids at rest, as required by the molecular-kinetic theory of heat . In: Annals of Physics . tape 17 , 1905, p. 549-560 , doi : 10.1002/andp.19053220806 .

- On the electrodynamics of moving bodies . In: Annals of Physics . tape 17 , 1905, p. 891–921 , doi : 10.1002/andp.200590006 ( fu-berlin.de [PDF]). Digitized as Wikilivres: On the electrodynamics of moving bodies

- Does the inertia of a body depend on its energy content? In: Annals of Physics . tape 18 , 1905, p. 639–641 , doi : 10.1002/andp.200590007 ( uni-augsburg.de [PDF]).

- On the principle of relativity and the conclusions drawn from it . In: Yearbook of Radioactivity . tape 4 , 1907, p. 411–462 ( soso.ch [PDF]). Digitized as Wikilivres: On the principle of relativity and the conclusions drawn from it

- Development of our views on the nature and constitution of radiation . In: Phys. Z. _ tape 10 , 1909, p. 817–825 ( ucsc.edu [PDF]).

- Influence of gravity on the propagation of light . In: Annals of Physics . tape 35 , 1911, p. 898–908 , doi : 10.1002/andp.200590033 ( uni-augsburg.de [PDF]).

- The formal basis of general relativity . In: Prussian Academy of Sciences, session reports . 1914, p. 1030-1085 , doi : 10.1002/3527608958.ch2 .

- On the general theory of relativity . In: Prussian Academy of Sciences, session reports . 1915, p. 778-786, 799-801 , doi : 10.1002/3527608958.ch3 .

- Explanation of the perihelion motion of Mercury from the general theory of relativity . In: Prussian Academy of Sciences, session reports . 1915, p. 831–839 , doi : 10.1002/3527608958.ch4 .

- The field equations of gravitation . In: Prussian Academy of Sciences, session reports . 1915, p. 844–847 , doi : 10.1002/3527608958.ch5 .

- The basis of the general theory of relativity . In: Annals of Physics . tape 49 , 1916, p. 769–822 , doi : 10.1002/andp.200590044 ( uni-augsburg.de [PDF]).

- with Wander Johannes de Haas : Experimental proof of Ampère's molecular currents . In: Negotiations of the German Physical Society . tape 17 , 1915, p. 152-170 .

- with Wander Johannes de Haas: Experimental proof of Ampère's molecular currents . In: Natural Sciences . tape 3 , 1915, p. 237-238 , doi : 10.1007/BF01546392 .

- Albert Einstein: On the quantum theory of radiation. In: Announcements from the Physical Society of Zurich. 18/1916 and Physical Journal 18/1917, p. 121 ff.

- with Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen : Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete? In: Phys. Rev. _ tape 47 , 1935, p. 777–780 , doi : 10.1103/PhysRev.47.777 ( princeton.edu [PDF]).

other works

- On the special and general theories of relativity . O.A., 1916, ISBN 3-540-42452-0 - general essay.

- Why war? Correspondence between Albert Einstein and Sigmund Freud. O.A., 1933, ISBN 3-257-20028-5 .

- My world view. OA 1934, 31st edition. Frankfurt 2010, ISBN 978-3-548-36728-6 .

- With Leopold Infeld : The Evolution of Physics. From Newton to Quantum Theory. O. A., 1938. German: The Evolution of Physics. ISBN 3-499-19921-1 .

- Why socialism? In: Monthly Review . 1949 (Einstein's essay was published in the first issue of the journal). English: Why Socialism?

- Out of my later years. O.A., 1950. English: From my late years. ISBN 3-548-34721-5 .

- Dear present and absent! Original sound recordings 1921–1951. soup. 2004, ISBN 3-932513-44-4 . ( audio sample. )

Online sources for Einstein's publications

- All of Einstein's publications in the annals of physics. His documents in the Annals of Physics 1901–1922 in facsimile .

- Another link to Einstein's work in the Annals of Physics in the original text .

- All of Einstein's articles in the proceedings of the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin.

- Einstein's work at the Posner Memorial Collection.

- The Einstein Site at Princeton University Press.

- Why socialism? Einstein's Confession of Socialism 1949 (German translation). First English edition in: Monthly Review (1949).

More texts

-

Alice Calaprice (ed.): The quotable Einstein. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1996, ISBN 0-691-02696-3 . Current edition 2011: The Ultimate Quotable Einstein. Online at: books.google.de.

- Einstein says: Quotations, ideas, thoughts. Partial translation from the American and supervision of the German edition: Anita Ehlers . Piper Verlag, Munich/Zurich 1997, ISBN 3-492-03935-9 . Further German new and special editions 1999, 2001, 2005 and 2007.

- Otto Nathan, Heinz north (ed.): Peace - world order or end of the world. Documentation of all available and preserved writings by Einstein on the subject of peace and the abolition of war. Parkland Verlag, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-89340-070-2 .

- Carl Seelig (ed.): My world view. Texts, essays and speeches. 1953

- With Mileva Marić : I'll kiss you orally on Sunday. 2005, ISBN 3-492-22652-3 . The Love Letters of 1897-1903 edited by Jürgen Renn and Robert Schulmann.

- Albert Einstein's letter to US President Roosevelt dated August 2, 1939.

- Albert Einstein: Principles of the Theory of Relativity. Vieweg, 1963,

- Luce Langevin-Dubus: Paul Langevin et Albert Einstein d'après une correspondence et des documents inédits. In: La Pensee. 1972

- Robert Schulmann (ed.): Soulmates - The correspondence between Albert Einstein and Heinrich Zangger (1910-1947). NZZ Libro , Zurich 2012, ISBN 978-3-03823-784-6 .

literature

biographies

- Nandor Balasz: Albert Einstein. in Dictionary of Scientific Biography , Vol. 4, Charles Scribner's, pp. 312–333, and John Stachel in The New Dictionary of Scientific Biography, 2008, Vol. 2, pp. 363–373.

- Thomas Buehrke: Albert Einstein. dtv, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-423-31074-X . (A biographical overview of Einstein's life.)

- Alice Calaprice , Daniel Kennefick, Robert Schulmann: An Einstein Encyclopedia. Princeton University Press, 2015.

- Ronald W. Clark : Albert Einstein - life and work, 100 years of relativity theory. Tosa Verlag, Vienna 2005, ISBN 3-85492-604-9 (the paperback edition was published in the 8th edition in 1988 by Heyne Verlag).

- Banesh Hoffmann , Helen Dukas : Albert Einstein. creator and rebel. Dietikon-Zurich, Belser 1976.

- Albrecht Folsing : Albert Einstein. Suhrkamp Verlag, 1995, ISBN 3-518-38990-4 .

- Ernst Peter Fischer : Einstein for the pocket. 2nd Edition. Piper, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-492-04685-1 .

-