Metz

| Metz | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Motto: “Si nous avons paix dedans, nous aurons paix au-dehors. »(German translation: If we keep peace inside, we will also have peace outside.) |

||

| region | Grand Est | |

| Department | Moselle | |

| Arrondissement | Metz | |

| Canton | Metz-1 , Metz-2 , Metz-3 | |

| Community association | Metz Métropole | |

| Coordinates | 49 ° 7 ' N , 6 ° 11' E | |

| height | 162-256 m | |

| surface | 41.94 km 2 | |

| Residents | 116,429 (January 1, 2017) | |

| Population density | 2,776 inhabitants / km 2 | |

| Post Code | 57000 | |

| INSEE code | 57463 | |

| Website | metz.fr | |

Pont Moyen (German Mittelbrücke ) over the right arm of the Moselle |

||

Metz (French [ mɛs ] or [ mɛːs ]; French out of date, German and Lorraine [ mɛts ]) is a town on the Moselle with 116,429 inhabitants (French Messins [ mɛsɛ̃ ] or Messines [ mɛsiːn ]; as of January 1, 2017) ) in north-eastern France . It is the capital of the Moselle department and was previously the capital of the former Lorraine region , which has been part of the Grand Est region since 2016 .

Metz was a center of the Merovingian and Frankish empires and the place of origin of the Carolingians . Between 1180 and 1210 it became an imperial city . In 1552 the French King Henry II occupied the city republic, which also fell de jure to France in the Peace of Westphalia in 1648.

geography

Metz is located at the mouth of the Seille in the Moselle .

history

Beginnings and first development

The first traces of settlement can be found from 3000 BC. Chr. Metz, whose old Celtic-Latin name is Divodurum Mediomatricorum ( Mediomatric Castle of the Gods), was named in the late Roman period after the Celtic tribe Mediomatricum (in the high medieval form Mettis or Metis ). The Celtic settlement was founded in 52 BC. It was conquered by the Romans in BC and developed into one of the largest cities in Gaul - located at the important intersection of the roads to Reims , Lyon , Trier , Strasbourg and Mainz . In the 2nd century the city had 40,000 inhabitants, making it larger than Lutetia ( Paris ). The first Christian communities were founded in the 4th and 5th centuries, with Clemens von Metz as the first bishop in the 4th century - the bishop's seat ( belonging to the Archdiocese of Trier ) from 535 onwards is certain . In 451, Metz became part of the army of the Hun King Attila destroyed.

In the Merovingian - Frankish times the city was the capital of the Frankish Eastern Empire, also known as Austrasia . During this time, the city of Metz flourished in cultural and religious areas. Sankt Chrodegang , Abbot of Gorze and Bishop of Metz, developed the first rules of life for the canonically living clerics or canons. The new plain-chant church chant was created at Gorze Abbey , later named Gregorian chant after Pope Gregory the Great .

Metz is the original headquarters of the Carolingians . Various family members of Charlemagne such as his wife Hildegard, his sisters, Emperor Ludwig the Pious and Karl's own son Drogo were buried in the monastery church of the Abbey of Sankt Arnulf . The great-grandfather of Charlemagne, Sankt Arnold (Saint Arnoul), and Charles's son Drogo also had offices as bishops of Metz.

During the Carolingian division of the empire after the death of Louis the Pious , Metz came to Lotharii Regnum in 843 and then to Eastern Franconia in 870 . The city made itself independent of the bishop in 1189.

Metz as a free imperial city

Between 1180 and 1210 Metz became an imperial city , created a domain, the Pays Messin, which rose to become the largest imperial city by area in the 14th century, and successfully repelled all attacks by the Dukes of Lorraine on their territory. The only thesis supported by a handwritten chronicle written in the 15th century , according to which firearms were first used by the city of Metz in 1324 , is controversial because the chronicler uses the words collevrines and, which were not used until the 15th century serpentines (German: Feldschlange ), and corresponding references in earlier sources such as the poem La guerre de Metz (1326) are missing. On the other hand, can not from these facts basically be concluded that in Metz not had firearms in use.

As in the neighboring free imperial city of Strasbourg , a city republic developed that was led by the richest patrician families (the Paraiges in the local Lorraine language , from Latin "Parentela" or "Paragium": clan). They formed a college of thirteen representatives, commonly called les Treize (the thirteen). The inhabitants of the free imperial city of Metz called themselves citains , whereby one can clearly recognize the Italian model of the autonomous Città . At that time, Metz maintained lively contact with the Italian trading cities and was home to numerous so-called "Lombard offices" that brought the money and credit business from northern Italy to Metz. The Jewish Ashkenazi community of Metz was one of the oldest in the Holy Roman Empire and later in France and for a long time played a decisive role in the exchange of money between the people and the authorities, but no Jews lived in Metz between around 1200 and 1550. The Bishop of Metz formally remained the head of the free city, but escaped the hustle and bustle of the rebellious city by settling in the residence of Vic-sur-Seille .

As early as the 9th century, the city of Metz had 39 churches and chapels and numerous monasteries and monasteries . The former Roman basilica of Saint-Pierre-aux-Nonnains is considered the oldest church in France. Beginning in the 12th and 13th centuries, orders of mendicants and knights were added, making Metz a predominantly spiritual city. The octagon of a Templar church from the 12th century with a Templar cross above the gate is still preserved . The cityscape of Metz remained largely dominated by monasteries until the 16th century. The arrival of the French from the 16th century put an end to this period. The city with a religious character was now transformed into a French fortress against the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation , to which it still belonged.

Metz under French rule

On April 10, 1552, with the consent of the Protestant imperial princes oppressed by Emperor Charles V , the French King Heinrich II occupied “the cities that have belonged to the empire from ancient times and are not German” ( Treaty of Chambord ), including alongside Metz also Toul , Verdun and Cambrai were counted. The citizens of Metz resisted in vain for eight days. The French king called this entry la chevauchée d'Austrasie (the ride to Austrasia), because he viewed this political success as a revenge for the loss of the Lorraine part of the empire by his Carolingian and Capetian ancestors. Henry II actually got the vicariate or protectorate over the so-called " three dioceses " Metz, Toul and Verdun (trois évêchés) . Although Catholicism was the state religion of the French kingdom, France often made pacts with the Protestant German princes in order to somehow dispute the European supremacy of the Catholic Habsburg "hereditary enemy". The same thing happened with Metz: only with the silent agreement of the Protestant imperial princes (the so-called prince conspiracy ) could the French king move into the free city of Metz, under the pretext of protecting the city from the Lorraine duke, who was the Roman-German emperor was devoted. Every attempt by Charles V to recapture the city of Metz failed. The French stayed in Metz until the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 officially and definitively granted them the three dioceses.

The fortress of Metz was considerably enlarged by Vauban in the 17th century and served as a hub for all of Louis XIV's campaigns in his reunification policy towards the east. In order to be able to occupy the fortress Metz with troops, the Caserne Coislin was built between 1726 and 1730 on the Champ à Seille. Medieval Metz was forgotten.

During the Franco-Prussian War , General François-Achille Bazaine withdrew to Metz with the French Army on the Rhine . After several weeks of siege by Prince Friedrich Karl's army, the army capitulated on October 27, 1870 and was taken prisoner two days later.

It was provisionally Lieutenant General v. Kummer appointed the fortress in command and the 26th Infantry Brigade appointed to garrison it. Shortly afterwards, Lieutenant General von Löwenfeld took their place as governor, Colonel von Brandenstein as commandant of Metz, and Count Henckel von Donnersmarck became civil governor.

History since 1871

From 1871 to 1918 in the time of the imperial monarchy and de facto again during the time of National Socialism from 1940 to 1944, Metz belonged to the German Empire .

1871-1914

Metz became the administrative seat of the newly created district of Lorraine within the realm of Alsace-Lorraine (with the capital Strasbourg ) and developed into the strongest fortified city in the German Empire. Before the Franco-Prussian War , Metz had 47,242 inhabitants, of whom only 1952 had given German as their mother tongue. The majority of the population was of the Catholic denomination, the Protestant community had around 1,000 members and the Jewish community had 1952 members. The residents of Metz, as part of the newly founded realm of Alsace-Lorraine, were given Alsace-Lorraine citizenship in accordance with the provisions of the Peace Treaty of Frankfurt , but had the option of retaining French citizenship until October 1, 1872. The original plan was that those who chose French citizenship (so-called optanten ) would have to leave the country. They were allowed to take their property with them or to sell them freely. According to the population census of 1872, Metz only had about 33,000 inhabitants, which means that around 15,000 Metzers had emigrated as a result of the annexation. A total of 160,878 inhabitants of the new Reichsland, i.e. around 10.4% of the total population, opted for French citizenship. The proportion of optants was particularly high in Upper Alsace, where 93,109 people (20.3%) said they wanted to keep French citizenship, and significantly lower in Lower Alsace (6.5%) and Lorraine (5.8%). Metz thus far exceeded the other areas with 31.75% emigrants. By 1873, 2000 people moved from the old German states, so that the city population rose again to 35,000.

| year | Civilians |

Catholics |

Protestants |

Jews |

Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 41,056 | 32,663 | 7045 | 1339 | 9 |

| 1885 | 42,555 | 32,837 | 8263 | 1397 | 58 |

| 1895 | 45,480 | 34,483 | 9609 | 1324 | 64 |

| 1905 | 47,384 | 36,185 | 9504 | 1622 | 73 |

| 1910 | 54,965 | 41,290 | 11,486 | 1849 | 340 |

For 1910, 13,633 military personnel in the city of Metz must be added, so that the city had a total of 68,598 inhabitants that year. The population growth between 1905 and 1910 was also a result of the 1908 incorporation of Plantières-Queuleu and Devant-les-Ponts, which together contributed 7,639 inhabitants. With regard to the population of 1910, only 20,932 people were born in Metz itself, 15,432 came from the rest of the Reich, 14,521 had moved from old Germany and 4080 came from abroad.

As a result of the emigration of some of the residents to France and above all through immigration and the stationing of German officials and military, the previously mostly French-speaking Metz temporarily became mostly German-speaking. The "old Germans" who moved in made up about half of the city's population in 1895. In the 1900 census, 78% of the Metz urban district gave German and 22% French as their mother tongue. In the district of Metz , however, the city has always remained a language island without even a single language corridor to the coherent German-speaking area in the east and north. In the district, 57.1% said French and 42.9% German as their mother tongue. In 1910, 13,731 of the city dwellers of Metz stated that they were French as their mother tongue (25%), 40.051 stated that they were German (73%) and 300 people stated that they grew up bilingual (0.54%). Church services were held in separate languages, there were German and French charitable associations, scientific societies, and theater and concert events with separate languages. The municipal council had protested massively against the annexation of the city in 1871. The mayoral election of 1871 resulted in the election of the Metz merchant Bezanson, who, after some hesitation, recognized the new balance of power. Nevertheless, his re-election was canceled by the German government in 1876 and in 1877 the then district director Julius von Freyberg-Eisenberg was appointed mayor's administrator, who was succeeded in 1880 by the previous district and police director Alexander Halm . It was not until 1886 that the old German Neu-Metzers were able to break the French majority in the municipal council elections. This made German the official language in the Council, and the minutes only had a French translation comment.

1914-1918

For Metz, which was only a few kilometers away from the German western front, the outbreak of the First World War became a particular burden due to the political differences in the city. In the years before the war, the city had become the most important outpost of the German Empire in the west. According to the Schlieffen Plan , the fortress of Metz was to secure the left wing against an attack by France as a central point within the German warfare on the western front. Mighty forts were built within a radius of 20 km and the new Metz train station ensured the relocation of entire divisions within a short time. As a result, the previous defensive walls around the city center were laid down, a new infrastructure laid out and the area rebuilt for residential and commercial purposes.

However, the city also retained its military character inside. 13,000 military personnel lived in the city alone, or about 25% of the total city population. The economy of the city of Metz depended heavily on the military. Numerous conscripts from all over the Reich served their time in Metz. The massive presence of old Germans and soldiers was felt by many long-time residents as a provocation and as a cementing of the city's affiliation to the unloved realm, so that in the irritable mood there were constant rivalries and conflicts. The writer Liesbet Dill writes about the contrast between old and new citizens: “The sharp contrasts prevailed there: German military, French bourgeoisie , Prussian officials, French old Lorraine clergy , fortress and old bishopric , on whose walls the war raged almost incessantly. And if it was n't an external war with mobilization and deployment , an internal struggle was constantly waged here, the result of which was only external war. ”The impending war caused an unbearable conflict of loyalty among the old Lorraine population. With the outbreak of war on August 1, 1914, the question of identity arose in all massiveness. It was clear to all of the city's residents that the outcome of the war would radically determine both the political future of Metz and individual lifestyles. Numerous old Metzgers hoped for a return to France, while the new Metzgers hoped that a victory for Germany would end once and for all the uncertain status of belonging to the city and the Lorraine region.

The city's French-language newspapers had to cease publication with effect from August 1, 1914, and the editors were expelled from the city. Foreign language newspapers were no longer available, allowing the military to manipulate public opinion in an uncontrolled manner. The German newspapers in Metz were careful not to run anti-French propaganda in view of the divided readership. In addition, they were subject to strict prior censorship.

With the outbreak of war, all civil authorities in the city were placed under the military. Basic rights were also restricted. Around 200 Metzgers classified as pro-French were immediately interned at the Ehrenbreitstein fortress in Koblenz , including prominent members of the Reich and Landtag. Entry and exit to and from the fortress city was only possible with a permit. All French street and authority names in Metz fell victim to a Germanization campaign in August 1914. Immediately after the outbreak of war, around 15,000 residents left the city in panic, suspecting a siege like in the war of 1870/1871. The Metz writer Adrienne Thomas has her fictional character Katherine write in her diary on the occasion of the outbreak of war in Metz: “Metz has lost its mind. Many families flee quickly. If you stay here, you buy everything you can find without a plan. "

The city administration promoted the wave of emigration by assuming the travel and accommodation costs. To the astonishment of many, the mobilization of soldiers from old Lorraine families or from long-established Metz families took place without incident and there were only a few desertions.

In the course of the war, statements interpreted as anti-German were severely punished. Even public conversation in French had been a criminal offense since July 1, 1915, which resulted in a penalty. The building up pressure on the population was to be released after the occupation of the city by France at the end of 1918.

The city was only threatened by the French military in the first few weeks of the war, when the front line on the western border of Lorraine was strengthened. Nevertheless, the city was threatened by French fighter pilots. Since the barracks were insufficient for the advancing soldiers, private houses were rededicated as quarters. The city's hospitals and educational institutions were also filled with wounded soldiers. In order to raise the morale of the city population, even the smallest reports of victory were read out publicly every evening from the balcony of the town hall on Paradeplatz by the mayor Roger Joseph Foret , who came from an old Lorraine family . In addition, the cathedral's Mütte bell rang solemnly every evening. At the same time, the municipal council felt called to publicly express its loyalty to “Kaiser and Reich” several times.

As the war progressed, the black market expanded rapidly because the administration had set maximum prices for the goods. From 1915 onwards, food had to be rationed and the population was called on to make savings, provide services and donate materials. There was an increasing number of women employed. From 1916, French property in the city was placed under compulsory administration. This involved around 900 houses and properties, the proceeds of which now flowed to the German state. In the same year, the city erected a memorial entitled “ The gray field in iron ”, in whose wooden base plates patriotic citizens could drive nails for a fee. The names of the donors were published in the local newspapers and the money raised went to the city's war welfare organization. All of these measures had the consequence that even the last sympathy for the German side disappeared in the long-established population. When it became clear in the late summer of 1918 that the war could no longer be won for the German Reich, many Neu-Metzers hoped for the promise of US President Woodrow Wilson that the population would benefit from the 14-point program of January 8, 1918 the right to shape the future political situation in the city of Metz.

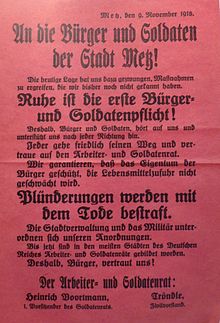

On November 9th , a workers 'and soldiers' council was formed in Metz, as in the neighboring city of Saarbrücken . The red flag was raised on the Metz town hall and the administrative tasks were taken over by the new council. When the French troops marched in on November 19, 1918, the councils in Metz and Saarbrücken were deposed. All previous elected officials were forced to resign. Pro-French people immediately took over the official business and organized the reception of the victorious Allied troops in Metz. Several truckloads of French tricolors were brought into the city from central France and the singing of the Marseillaise was rehearsed. All the German monuments in the city were hastily razed. The metals obtained in this way were poured into victory medals. The entry of the victorious troops, the French heads of state and the important French military was enthusiastically celebrated by many old butchers, while the new butchers hid in their apartments.

1918-1940

After the armistice in November 1918, the occupation by French troops and the signing of the Versailles Treaty in 1919, the city returned to France. The new balance of power led to a pogrom-like anti-German mood in the city, which was massively fueled by the new mayor Charles Victor Prevel, who threatened the German-speaking butchers with draconian punishments. As a result, many so-called old Germans, i.e. immigrants from the rest of Germany since 1871, were expelled from the city and the country and the leadership positions were filled with French. The old Germans had to leave the territory of the former Reichsland for Germany within 24 hours; each adult was allowed to take 30 kg of luggage with them and each family was allowed to take 2,000 marks in cash . The remaining possessions were confiscated by the French state and sold cheaply by the authorities to other Metz citizens. The Metz writer Ernst Moritz Mungenast lets his fictional character Andreas Muzot characterize the situation of such a war profiteer in a bitter and polemical way: “He slept in the beds of the displaced, wore their shirts and underpants, ate from their plates with their cutlery, slumbered on their sofas and divans and went through the streets with their walking sticks, occasionally checking their clocks or blowing their nose on their handkerchiefs. "

A plebiscite like in the year 1871/1872 there was not, as it officially forward the slogan: Pas de plebiscite! On ne choisit pas sa mère (German translation: No referendum! You don't vote for your mother). In addition, a vote appeared superfluous, as the cheers at the greeting of the French troops were interpreted as testimony to the deep desire of the Lorraine and Alsatians to become French again. On December 5, 1918, the French National Assembly finally passed the "inviolable right of the Alsace-Lorraine people to remain members of the French family". At the solemn handover ceremony on the occasion of the reintegration of the city of Metz into French territory, the French President Raymond Poincaré made it clear on December 8, 1918, in the presence of Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau , Marshals Ferdinand Foch and Philippe Pétain and the American General John J. Pershing that a plebiscite did not take place, proclaiming: “Your reception proves to all the Allied nations how right France was when it asserted that the heart of Lorraine and Alsace has not changed.” After an intervention by American President Wilson , they returned after a year many of those who had previously been deported returned. A total of 20,000 people had to leave the city of Metz. In Lorraine there were a total of around 100,000. The language relationship was reversed after the French conquest of Metz in the interwar period . For the 1920s, a German-speaking population in the city of about 30% is assumed.

1940-1945

On June 14, 1940, Metz was declared an open city ; On the afternoon of June 17, a motorized patrol of the 379th Infantry Regiment of the Wehrmacht drove into the deserted city. Troops of the 16th Infantry Division occupied Metz without a fight. After the surrender-like armistice of Compiègne , Alsace-Lorraine was effectively annexed to the National Socialist German Reich . Adolf Hitler demonstratively celebrated the first Christmas after the victory over France in Metz in 1940. As early as September 10, 1940, the surrounding communities were Montigny-lès-Metz, Longeville-lès-Metz, Le Ban-Saint-Martin, Saint-Julien-lès-Metz, Vallières, Borny, La Maxe, Magny, Moulins, Plappeville, Scy -Chazelles, Sainte-Ruffine and Woippy have been incorporated into the municipal area of Metz. As head of civil administration in Lorraine, Josef Bürckel acted from Saarbrücken.

In November 1944, the liberation of Metz by troops of the 3rd US Army marked the climax of the Battle of Lorraine.

From 1945

The Moselle canalisation (1958 to 1964) made the Moselle navigable for ships up to 1500 tons as far as Metz.

In 1961, Metz merged with the neighboring communities of Borny , Magny and Vallières-lès-Metz .

Demographics

| year | population | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1871 | 51,388 | with the garrison; Civilians on December 1: 39,993 in 11,285 households, including 35,982 Catholics, 2502 Protestants, 13 other Christians and 1496 Jews |

| 1872 | 54,817 | |

| 1880 | 53,131 | with the military; According to other data, 41,056 civilians, including 32,663 Catholics, 7045 Evangelicals, 1339 Jews , nine others |

| 1885 | 54,072 | with the military; 42,555 civilians, including 32,837 Catholics, 8,263 Protestants, 1,397 Jews, 58 others |

| 1890 | 60.186 | with the military, of which 17,183 Protestants, 41,693 Catholics, 1434 Jews |

| 1895 | 45,480 | Civilians, including 34,483 Catholics, 9609 Protestants, 1,324 Jews, 64 others |

| 1900 | 58,462 | with the military, including 16,480 Evangelicals, 40,444 Catholics |

| 1905 | 60,791 | with the garrison ( infantry regiments No. 67, 98, 130, 131, 145 and 174, as well as No. 4 and 8 from the Bavarian Army, two dragoon regiments No. 9 and 13, two field artillery regiments No. 33 and 34 and a field artillery division No. 70, two foot artillery regiments No. 8 and 12 and two battalions of Bavarian foot artillery No. 2, two engineer battalions No. 16 and 20, a machine gun division No. 11, a total of approx. 900 officers and 24,000 men), of which 17,452 Evangelicals, 41,805 Catholics, 1466 Jews; According to other information, 47,384 civilians, including 36,185 Catholics, 9504 Evangelicals, 1622 Jews, 73 others |

| 1910 | 68,598 | with the military, including 18,748 Evangelicals, 47,575 Catholics; according to other data 54,965 civilians, including 41,290 Catholics, 11,486 Evangelicals, 1,849 Jews, 340 others |

| year | 1962 | 1968 | 1975 | 1982 | 1990 | 1999 | 2007 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residents | 102,771 | 107,537 | 111,869 | 114,232 | 119,594 | 123.704 | 123,580 | 117,492 |

politics

mayor

The last mayors of Metz were:

- Raymond Mondon, 1947 to 1970

- Jean-Marie Rausch, 1971 to 2008

- Dominique Gros, since 2008

Twin cities

-

Gloucester ( United Kingdom ) (1967)

Gloucester ( United Kingdom ) (1967) -

Kansas City ( USA , Missouri ) (2004)

Kansas City ( USA , Missouri ) (2004) -

Karmi'el ( Israel ) (1987)

Karmi'el ( Israel ) (1987) -

Königgrätz (Hradec Králové) ( Czech Republic ), since December 1, 2001

Königgrätz (Hradec Králové) ( Czech Republic ), since December 1, 2001 -

Luxembourg ( Luxembourg ) (1952)

Luxembourg ( Luxembourg ) (1952) -

Saint-Denis ( Réunion , France ) (1986)

Saint-Denis ( Réunion , France ) (1986) -

Trier ( Germany ), since October 13, 1957; see also: Quattropole

Trier ( Germany ), since October 13, 1957; see also: Quattropole

-

Yichang ( PR China ) (1991)

Yichang ( PR China ) (1991) -

Djambala ( Republic of the Congo ) since May 2012

Djambala ( Republic of the Congo ) since May 2012

badges and flags

Blazon : " Split silver and black."

Motto: “Si nous avons paix dedans, nous aurons paix au-dehors. »-“ If we have peace inside, we will have peace outside. ”The city motto was originally carved over the tower-flanked gateway of the barbarian. The inscription, which is currently in the Cour d´Or city museum in Metz after the city gate was demolished in 1904, was created in connection with a medieval popular uprising. In the years 1324 to 1326 there was a conflict between the patrician city government, the Paraiges, with the Count of Luxembourg, John of Bohemia , the Archbishop of Trier, Baldwin of Luxembourg , the Count of Bar, Edward I , and the Duke of Lorraine, Friedrich IV. , Come. The so-called " War of the Four Lords " was contractually ended on March 3, 1326, but as a result of the devastating economic situation, a popular uprising broke out in August 1326, in which the patrician upper class of the Free Imperial City of Metz was expelled. They then besieged the city and were able to force the restitution of the old balance of power through starvation. The inscription demonstratively affixed above the barbarian should call every city citizen to reason and lead to the acceptance of the balance of power.

A small poem from 1541 in French and Latin explains the white and black city arms as follows:

Qui les couleurs voudra savoir

De nos armes? C'est blanc et noir.

C'est que par blanc: "Vita bonis"

Et par le noir: "Mors est malis"

(German translation: Who would like to know the colors of our coat of arms? It is white and black. White stands for: "Life for the good" and black for: "Death for the bad".)

Culture and sights

The years of membership in the German Empire up to 1918 had a strong impact on the Metz cityscape and were particularly evident in military and civil architecture (e.g. train station , today still medallions of the Hohenzollern emperors). To this day one can easily distinguish the “German” or “Prussian” from the “French” Metz. This duality is part of the history of the city, similar to Strasbourg . In contrast to Strasbourg, where the majority of German was spoken, Metz was and remained a predominantly French-influenced city.

Churches

- Sainte-Glossinde Abbey

- former Abbey of Sankt Arnulf

- Gothic cathedral Saint-Étienne de Metz (St. Stephen's Cathedral) (with 6500 m² church windows, designed by Marc Chagall , among others )

- Monastery of the Recollects in Metz

- Reformed Church: Temple Neuf (Protestant City Church Metz)

- Notre-Dame de l'Assomption

- Saint-Eucaire

- Saint-Livier

- Sainte-Lucie (with the 12th century choir tower )

- Saint Martin

- Saint-Maximin (with windows by Jean Cocteau )

- Saint-Pierre-aux-Nonnains (also Saint-Pierre-de-la-Citadelle , St. Peter on the Citadel or St. Peter to the Nuns in the Rue de la Citadelle ), basilica from the 4th century

- Saint Vincent

- Sainte-Ségolène (13th / 14th / 19th centuries)

- Templar Chapel

Places

- 13./15. Century: Place Saint-Louis, Place Sainte-Croix, Place Saint-Jacques

- 18th century: Place de la Comédie, Place d'Armes , Place Saint-Thiébault, Place de France

- Provision magazine

Townhouses

- Hôtel de Gargan , historical building complex from the 15th century

- Hôtel Saint-Livier , from the 13th and 16th / 17th centuries century

- Hôtel de Ville (town hall), from the 18th century

Public buildings from the period between 1871 and 1918

- Palais du Gouverneur, built 1902–1905

- Poste centrale (main post office), built 1905–1911, architect Jürgen Kröger

- Gare de Metz-Ville (main station), built 1905–1908, architect Jürgen Kröger

Remains of the city fortifications

- Porte des Allemands (German Gate)

- Porte Serpenoise (Roman Gate)

- Tour Camoufle (Camuffel Tower)

Theater and function rooms

- Grand Théâtre

- Quartier Impérial , Wilhelmine district of the early 20th century.

- Les Arènes, modern event hall for sporting events and rock concerts, built 2000–2001, architect Paul Chemetov

- Arsenal de Metz, a large modern concert hall in the old armory, also regularly offers art exhibitions, built 1987–1989, architect Ricardo Bofill

Museums

- Art History Museum - Musée d'Art et d'Histoire

- Municipal Museum - Cour d'Or

- Regional contemporary art collection - Fonds Régional d'Art Contemporain (49 Nord 6 Est - Frac Lorraine) in the Hôtel Saint-Livier

- The Center Pompidou-Metz is a contemporary art center and was opened in May 2010.

Every summer Metz hosts the literary festival L'Été du Livre.

Economy and Infrastructure

Metz is the seat of the Chambre de Commerce et d'industrie de la Moselle , the Chamber of Commerce and Industry for the Moselle department.

traffic

In terms of road traffic, Metz is on the important north-south and east-west connections: Metz is crossed by the (former) Route nationale 3 Paris - Saarbrücken, from which the (former) Route nationale 53 (to Luxembourg [City]), route National 55 (to Saarburg) and Route nationale 57 (to Besançon) branch off.

Since the Moselle canalisation, the port through which the export of grain is handled (the most important inland port for the handling of grain in France) has been of greatest importance for Metz . For industry and trade, the connection to the rail network and the connection to the road traffic routes are also very important.

Metz is well connected to the European rail network. The TGV Est runs from Paris between Metz and Nancy ( Lorraine TGV train station , only bus connection) and on to Strasbourg . Metz was the end point of a strategic railway line , the so-called Kanonenbahn , from Berlin via Wetzlar and Koblenz . The Metz train station was built for this purpose .

The Aéroport Metz Nancy Lorraine is located about 30 km south of the city of Metz on the A31 . The civil airport of Metz is not of great importance as its catchment area is relatively small. From here, mainly domestic French destinations and holiday destinations in the Mediterranean area are served. In the past, the nearby Metz-Frescaty military airfield was used for civilian purposes.

In October 2013, the new Mettis traffic system with two diameter lines was put into operation. Diesel-electric double articulated buses run on separate concrete lanes. The vehicles have a capacitor store to recover energy when braking.

Established businesses

Ikea France has its main distribution center in Metz.

The Metz trade fair hosts several trade fairs every year on 34,000 square meters.

Public facilities

The Lorraine regional parliament has its seat in Metz. The city has been the seat of the diocese of Metz since 535 .

university

The central campus of the Université Paul Verlaine de Metz is located on the Île du Saulcy and has been part of the Université de Lorraine since January 2012 . The Faculties of Mathematics, Computer Science and Mechanics, Social Sciences and Arts, Literature and Linguistics, and Law, Economics and Administration are located here, as well as several smaller institutes, the Arts et Métiers ParisTech , the CentraleSupélec , the École supérieure d'électricité , the Ecole nationale d'Ingénieurs de Metz , the university administration, a library and a theater.

Further university facilities are located in the Bridoux district (Faculty of Biology and Environmental Studies) and in the Technopôle district (Faculties of Management, Applied Sciences, Physics, Electrical Engineering and Metrology, individual departments of the Faculty of Social Sciences).

The university also has branches in Thionville , Sarreguemines , Saint-Avold and Forbach .

graveyards

- War cemetery Metz (French: Nécropole nationale de Metz-Chambière) with war graves of several nations from the wars Franco-German War , First World War , Second World War .

- Cimetière de l'Est

tourism

In addition to the sights mentioned above, several parks invite you to relax. The largest local recreation area is the Parc de la Seille , which stretches along the small river Seille in the south of the city. On the Plan d'Eau, a former branch of the Moselle on the Île du Saulcy not far from the old town, pedal boats, canoes and rowing boats are for hire. Many tame swans also live there.

The old fortifications are ideal for walks, on the one hand along the Moselle near the Porte des Allemands, on the other hand the fortress of Queuleu.

Every year in August, the city of Metz holds the traditional Mirabelle Festival (Fête de la Mirabelle).

Sports

Metz is represented in French football by FC Metz . Between 1967 and 2002, the club always played in the top French division, Ligue 1 . Since then, the Grénats have mostly played in Ligue 2 . In 2016, the club rose again to Ligue 1. The club has its own stadium with a capacity of around 25,000 in the western suburb of Longeville-lès-Metz , the Stade Saint-Symphorien .

In women's handball , Metz Handball plays in the first French league.

Every year an ATP tournament of the 250 class takes place in Metz.

The central sports facility is the Palais Omnisport les Arènes , which is located in the Parc de la Seille in the immediate vicinity of the new Center Pompidou-Metz. The large hall is used for sporting events, but also for non-sporting major events.

Culinary specialties

- Mirabelle plums , processed in various ways: sweets, schnapps, jams, cakes, etc.

- Boulets de Metz , a confectionery specialty (actually nothing more than two macaroons with mirabelle ice cream in between)

Idioms

In the Saarland-Luxembourg region, the phrase “drive snails to Metz” means “ to carry owls to Athens ”, ie to do something useless.

Another saying goes "... as solid as Metz". With reference to the strong fortress ring that surrounded Metz, the phrase expresses the firmness or immobility of a thing.

Another saying in Saarland for bustling activity is the common expression "It's like the Metz train station!"

Personalities

literature

(in alphabetic order)

- Johann H. Albers: The siege of Metz. Events and conditions inside the fortress from August 19 to October 28, 1870, according to French sources and verbal reports . Two lectures. Along with a map of the Metz area. Scriba, Metz 1896 ( digitized version ).

- Sylvie Becker, Francis Kochert: Metz and the surrounding area. Hachette tourisme, 2009, ISBN 978-2-01-244787-5 .

- René Bour: Histoire de Metz. Éditions Serpenoise, Metz 1990, ISBN 2-901647-08-1 .

- Aurélien Davrius: Metz in the 17th and 18th centuries, Towards urban planning of the Enlightenment. German Transfer from Margarete Ruck-Vinson (Èditions du patrimoine, Center des monuments nationaux), Paris 2014.

- Guy Halsall: Settlement and Social Organization, The Merovingian Region of Metz. Cambridge 1995.

- François-Yves Le Moigne: Histoire de Metz. Private, Toulouse 1986.

- Philippe Martin: Metz 2000 years of history. Éditions Serpenoise, Metz 2007, ISBN 978-2-87692-739-1 .

- Christiane Pignong-Feller: Metz 1900–1939, an imperial architecture for a new city. German Transfer from Margarete Ruck-Vinson (Èditions du patrimoine, Center des monuments nationaux), Paris 2014.

- Horst Rohde and Armin Karl Geiger: Military history travel guide Metz. Hamburg 1995.

- Matthias Steinbach: Abyss Metz. War experience, everyday siege life and national education in the shadow of a fortress 1870/71 . (Paris Historical Studies; 56). Oldenbourg, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-486-56609-1 ( digitized ).

- Pierre-Édouard Wagner: The medieval Metz. A patrician republic. German Transfer from Margarete Ruck-Vinson (Èditions du patrimoine, Center des monuments nationaux), Paris 2014.

- Westphal (without first name): History of the city of Metz. I. Part, Up to the year 1552, II. Part, Up to the year 1804, III. Theil, Until the Peace of Frankfurt in 1871. German bookstore (Georg Lang), Metz 1875-1878 ( digitized version ).

- Niels Wilcken: From the Graully Dragon to the Center Pompidou-Metz, Metz, a cultural guide. Merzig 2011.

- Gaston Zeller: La Réunion de Metz à la France. 2 volumes, Strasbourg 1926.

- Older descriptions

- Georg Lang: The government district of Lorraine. Statistical-topographical handbook, administrative scheme and address book , Metz 1874, pp. 71–79 and p. 354 ( online )

- Eugen H. Th. Huhn: German-Lorraine. Landes-, Volks- und Ortskunde , Stuttgart 1875, pp. 171–260 ( online ).

- Metz , in: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon . 6th edition, Volume 13, Leipzig / Vienna 1908, pp. 722–725 ( Zeno.org )

Web links

- Metz . In: Meyers Konversations-Lexikon . 4th edition. Volume 11, Verlag des Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1885–1892, p. 551.

- Metz. In: Johann Heinrich Zedler : Large complete universal lexicon of all sciences and arts . Volume 20, Leipzig 1739, column 1403-1407.

- Office du Tourisme

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ville de Metz: Histoire de la ville ( Memento of the original from August 17, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed April 7, 2013.

- ^ Cf. Mémoires de la Société d'Archéologie et d'Histoire de la Moselle, Librairie de l'Académie Impériale, Rousseau-Pallez Editeur, 1860 Paris, and James Riddick Partington : A history of Greek fire and gunpowder W. Heffer & Sons Ltd., Cambridge 1960; Reprint Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999 Baltimore, Maryland, ISBN 0-8018-5954-9 .

- ^ Westphal, above given name: History of the city of Metz. Deutsche Buchhandlung (G. Lang), Part I, Until 1552. Metz 1875, p. 119.

- ↑ http://www.xn--jdische-gemeinden-22b.de/index.php/gemeinden/mo/2393-metz-lothringen

- ↑ Sophie Charlotte Preibusch: Constitutional developments in Alsace-Lorraine from 1871 to 1918. In: Berliner Juristische Universitätsschriften, Fundamentals of Law. Volume 38. ISBN 3-8305-1112-4 , p. 96; ( Google digitized version ).

- ^ Folz, above surname: Metz as the German district capital (1870–1913). In: A. Ruppel (Ed.): Lothringen and his capital. A collection of orienting essays. Metz 1913, pp. 372-383.

- ^ Thomas Nipperdey: German history. 1866-1918. Volume 2: Power state before democracy. Beck, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-406-34801-7 , p. 72.

- ↑ Many German generals were born here. Among them Hans von Salmuth , Rudolf Schmundt , Eugen Müller and Edgar Feuchtinger .

- ↑ Christophe Duhamelle, Andreas Kossert, Bernhard Struck (eds.): Grenzregionen. A European comparison from the 18th to the 20th century. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 3-593-38448-5 , p. 66.

- ^ Folz, above surname: Metz as the German district capital (1870–1913). In: A. Ruppel (Ed.): Lothringen and his capital. A collection of orienting essays. Metz 1913, pp. 372-383.

- ↑ Rolf Wittenbrock: The city expansion of Metz (1898-1903). National interests and areas of conflict in a fortified town near the border. In: Francia, 18/3 (1991), pp. 1-23.

- ↑ Christiane Pignong-Feller: Metz 1900–1939. An imperial architecture for a new city. German Transfer from Margarete Ruck-Vinson (Èditions du patrimoine, Center des monuments nationaux), Paris 2014.

- ↑ Strasbourg Citizens' Newspaper, July 7, 1914.

- ↑ Archives Départementales de la Moselle, 3 AL 323, letter from the local SPD association to the mayor of Metz dated November 17, 1913.

- ^ Liesbet Dill: Lothringer Grenzbilder. Leipzig undated (1919/1929), p. 8.

- ↑ Rolf Wittenbrock: “The mightiest bulwark in our Westmark.” Saarbrücken's neighboring city of Metz during the war. In: "When the war came over us ..." "The Saar region and the First World War. Catalog for the exhibition of the Regional History Museum in Saarbrücken Castle. Saarbrücken 1993, Merzig 1993, pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Rolf Wittenbrock: “The mightiest bulwark in our Westmark.” Saarbrücken's neighboring city of Metz during the war. In: "When the war came over us ..." The Saar region and the First World War. Catalog for the exhibition of the Regional History Museum in Saarbrücken Castle. Saarbrücken 1993, Merzig 1993, p. 112.

- ^ François Roth: La Lorraine annexée (1870-1918). Nancy 1976, p. 595.

- ^ Archives Municipales, Metz, 4 H, 57, order of August 24, 1914.

- ↑ Adrienne Thomas: The Katherine becomes a soldier. A novel from Alsace-Lorraine. Berlin 1920, p. 130.

- ^ Laurette Michaux: La Moselle pendant la guerre (1914-1918). Metz 1988, p. 29.

- ↑ Bruno Weil: Alsace-Lorraine and the war. Strasbourg and Leipzig 1914, p. 47.

- ^ François Roth: La Lorraine annexée (1870-1918). Nancy 1976, p. 597.

- ^ François Roth: La Lorraine annexée (1870-1918). Nancy 1976, p. 597.

- ^ Archives Municipales, Metz, Metz Municipal Council, minutes of the meeting of August 3, 1914, p. 198.

- ^ Archives Municipales, Metz, 4 H, 65.

- ↑ Archives Municipales, Metz, Metz Municipal Council, minutes of the meeting of August 14, 1914, p. 204.

- ^ Laurette Michaux: La Moselle pendant la guerre (1914-1918). Metz 1988, p. 157.

- ^ Archives Municipales, Metz, 4 H, 65.

- ^ François Roth: La Lorraine annexée (1870-1918). Nancy 1976, p. 629.

- ^ François Roth: La Lorraine annexée (1870-1918). Nancy 1976, p. 608.

- ↑ Rolf Wittenbrock: “The mightiest bulwark in our Westmark.” Saarbrücken's neighboring city of Metz during the war. In: "When the war came over us ..." The Saar region and the First World War. Catalog for the exhibition of the Regional History Museum in Saarbrücken Castle. Saarbrücken 1993, Merzig 1993, p. 119.

- ↑ Archives Municipales, Metz, 4 H, 2.

- ^ François Roth: La Lorraine annexée (1870-1918). , Nancy 1976, p. 647 f.

- ↑ Metz - goodbye. In: Saarbrücker Zeitung from November 19, 1918.

- ↑ Rolf Wittenbrock: “The mightiest bulwark in our Westmark.” Saarbrücken's neighboring city of Metz during the war. In: "When the war came over us ..." The Saar region and the First World War. Catalog for the exhibition of the Regional History Museum in Saarbrücken Castle. Saarbrücken 1993, Merzig 1993, pp. 109-123.

- ^ Proclamation du Maire de Metz, November 25, 1918. In: Laurette Michaux: La Moselle pendant la guerre (1914-1918). Metz 1988, p. 189.

- ↑ Ernst Moritz Mungenast: The magician Muzot. Dresden 1939, p. 753.

- ^ Jean-Claude Berrar: Memoire en Images. Metz / Saint-Avertin 1996, pp. 109-114.

- ↑ Philippe Wilmouth: Images de Propagande. L'Alsace-Lorraine de l'annexion à la Grande Guerre 1871-1919. Vaux 2013, pp. 164–166.

- ^ Suzanne Braun: Metz, Portrait d'une ville. Metz 2008, p. 9.

- ↑ Rolf Wittenbrock: “The mightiest bulwark in our Westmark.” Saarbrücken's neighboring city of Metz during the war. In: "When the war came over us ..." The Saar region and the First World War. Catalog for the exhibition of the Regional History Museum in Saarbrücken Castle. Saarbrücken 1993, Merzig 1993, pp. 109-123.

- ^ Philippe Schillinger: Metz, de l'Allemagne à la France 1918-1919. In: Annuaire de la Société d'Histoire et d'Archéologie de la Lorraine 74, 1974, pp. 123-131.

- ↑ Philippe Wilmouth: Images de Propagande. L'Alsace-Lorraine de l'annexion à la Grande Guerre 1871-1919. Vaux 2013, pp. 164–166.

- ↑ Christian Fauvel: Metz 1940–1950. De la tourmente au renouveau. Metz 2017, pp. 56, 82-83.

- ^ Georg Lang (ed.): The government district of Lorraine. Statistical-topographical manual, administrative schematic and address book , Metz 1874, p. 72 ( online ).

- ^ Complete geographic-topographical-statistical local lexicon of Alsace-Lorraine. Contains: the cities, towns, villages, castles, communities, hamlets, mines and steel works, farms, mills, ruins, mineral springs, etc. with details of the geographical location, factory, industrial and other commercial activity, the post, railway u. Telegraph stations and the like historical notes etc. Adapted from official sources by H. Rudolph. Louis Zander, Leipzig 1872, Sp. 39 ( online )

- ↑ a b c d e M. Rademacher: German administrative history from the unification of the empire in 1871 to the reunification in 1990. (Online material for the dissertation, Osnabrück 2006)

- ^ Meyer's Large Conversational Lexicon . 6th edition, Volume 13, Leipzig / Vienna 1908, pp. 722–725 ( Zeno.org )

- ↑ Pierre-Édouard Wagner: The medieval Metz, Eine Patrizier Republik, German translation by Margarete Ruck-Vinson (Èditions du patrimoine, Center des monuments nationaux), Paris 2014, p. 11.

- ↑ Magnus-Henry Will: Metz et ses environs, Metz 1919, p. 3.

- ↑ http://opera.metzmetropole.fr/ ( Memento of the original from June 15, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ http://tout-metz.com/

- ↑ www.arenes-de-metz.com

- ↑ www.arsenal-metz.fr ( Memento of the original dated September 23, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ "Journées inaugurales" (opening days) . ( Memento from July 14, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (German / French / English)

- ↑ A city is on the track ( Memento from October 15, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), DRadio Wissen on June 25, 2013.

- ↑ [1]

- ^ Saarpfalz-Kreis (Ed.): Saarpfalz - Blätter für Geschichte und Volkskunde (1993), Issue 36, p. 43.

- ^ Niels Wilcken: From the dragon Graully to the Center Pompidou-Metz, Metz - a cultural guide. Merzig 2011, p. 16.

- ^ Niels Wilcken: From the dragon Graully to the Center Pompidou-Metz, Metz - a cultural guide. Merzig 2011, p. 16.