St. Polten

|

Statutory city St. Polten

|

||

|---|---|---|

| coat of arms | Austria map | |

|

|

||

| Basic data | ||

| Country: | Austria | |

| State : | Lower Austria | |

| Political District : | Statutory city | |

| License plate : | P | |

| Surface: | 108.44 km² | |

| Coordinates : | 48 ° 12 ' N , 15 ° 38' E | |

| Height : | 267 m above sea level A. | |

| Residents : | 55,514 (January 1, 2020) | |

| Postcodes : | 3100, 3104, 3105, 3107, 3140, 3151, 3385 | |

| Area code : | 02742 | |

| Community code : | 3 02 01 | |

| NUTS region | AT123 | |

| Address of the municipal administration: |

Rathausplatz 1 3100 St. Pölten |

|

| Website: | ||

| politics | ||

| Mayor : | Matthias Stadler ( SPÖ ) | |

|

Municipal Council : (2016) (42 members) |

||

| Location of St. Pölten | ||

St. Polten |

||

| Source: Municipal data from Statistics Austria | ||

St. Pölten (official name, also written Sankt Pölten , pronounced Bavarian-Austrian St. Pödn ) has been the state capital since 1986 and, with 55,514 inhabitants (as of January 1, 2020), the largest city in Lower Austria . In terms of population, St. Pölten ranks ninth on the list of cities in Austria .

The city in the foothills of the Alps on the Traisen River has an area of 108.44 km² and, as a statutory city, is both a municipality and a district . The area of St. Pölten has been inhabited since the Stone Age, the city is - depending on the definition - referred to as the or at least one of the oldest cities in Austria . On November 17, 2016, St. Pölten was awarded the title of “ Reformation City of Europe ” as the seventy-fifth city by the Community of Evangelical Churches in Europe . In September 2017, the application for European Capital of Culture 2024 was made in cooperation with the state of Lower Austria .

geography

The city is located in the northern Alpine foothills south of the Wachau . It is therefore part of the Mostviertel , the southwest of the four quarters of Lower Austria.

City structure

|

structure

|

||||||

|

Legend for the breakdown table

|

St. Pölten is divided into eleven districts, which are divided into a total of 42 cadastral communities.

- Harland : Altmannsdorf, Windpassing

- Ochsenburg : Dörfl near Ochsenburg

- Pottenbrunn : Pengersdorf, Wasserburg, Zwerndorf

- Radlberg : Oberradlberg, Unterradlberg

- Ratzersdorf ( KG : Ratzersdorf an der Traisen )

- Spratzern : Matzersdorf, Pummersdorf, Schwadorf, Völtendorf

- Stattersdorf

- St. Georgen am Steinfelde : Eggendorf, Ganzendorf, Hart, Kreisberg, Mühlgang, Reitzersdorf, Steinfeld, Wetzersdorf, Wolfenberg, Wörth

- St. Pölten : Hafing, Nadelbach, Teufelhof, Waitzendorf, Witzendorf

- Viehofen : Ragelsdorf, Weitern

- Wagram : Oberwagram, Ober Zwischenbrunn, Unterwagram, Unter Zwischenbrunn

With the exception of the districts of Wagram and Radlberg, there are also cadastral communities with the same names.

The municipality includes the following 42 localities (population in brackets as of January 1, 2020):

- Altmannsdorf (127)

- Dörfl (19)

- Eggendorf (1206)

- Ganzendorf (81)

- Hafing (33)

- Harland (1571)

- Hard (1227)

- Kreisberg (25)

- Matzersdorf (29)

- Mill passage (535)

- Nadelbach (76)

- Oberradlberg (498)

- Oberwagram (4139)

- Ober Zwischenbrunn (65)

- Ochsenburg (333)

- Pengersdorf (52)

- Pottenbrunn (2414)

- Pummersdorf (99)

- Ragelsdorf (781)

- Ratzersdorf an der Traisen (1680)

- Reitzersdorf (3)

- St. Georgen am Steinfelde (391)

- St. Poelten (22,352)

- Schwadorf (28)

- Spratzern (6507)

- Stattersdorf (1899)

- Steinfeld (116)

- Teufelhof (547)

- Unterradlberg (783)

- Unterwagram (2301)

- Unter Zwischenbrunn (38)

- Viehofen (4564)

- Voeltendorf (132)

- Waitzendorf (334)

- Moated castle (77)

- Next (169)

- Wetzersdorf (12)

- Windpassing (57)

- Witzendorf (75)

- Wolfenberg (17)

- Worth (64)

- Zwerndorf (58)

Neighboring communities

The municipalities border on St. Pölten (clockwise from the north):

- Herzogenburg , Kapelln , Böheimkirchen , Pyhra , Wilhelmsburg , Ober-Grafendorf , Gerersdorf , Neidling , Karlstetten and Obritzberg-Rust .

Neighboring district

Only the district of St. Pölten borders the statutory city of St. Pölten .

climate

The extra-alpine climate of St. Pölten is determined by moderately cold, rather cloudy winters with little snow and summers with a lot of sun and little precipitation.

The long-term monthly mean temperature fluctuates between −1.0 ° C in January and 19.1 ° C in July, the annual mean is 9.2 ° C. The average amount of precipitation is lowest at 29.5 mm in January and increases to 88.1 mm in July. Most rainy days are recorded in the summer months of June and July with 10.5 and 10.7 days, while October only rains 6.5 days. July is the sunniest month with an average of 7.6 hours of sunshine per day , while December only shines for 1.5 hours.

| St. Polten | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate diagram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Monthly average temperatures and precipitation for St. Pölten

Source: Climate data from Austria 1971–2000. ZAMG , St. Pölten station .

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

history

Stone Age to Iron Age

The area of today's St. Pölten was already in the Neolithic , around the 3rd millennium BC. BC, settled; there are numerous finds of the painted ceramic culture. Traces of the Bronze Age , the Iron Age and the Celts have also been found.

The Roman city of Aelium Cetium

From the end of the 1st century AD until around 450 the Roman city of Aelium Cetium was located exactly where the old town of St. Pölten was built in the Middle Ages. Aelium Cetium was one of the most important civil supply towns in the Roman province of Noricum , from which one could reach several border towns on the Danube occupied by soldiers in a day's march. Archaeologists have been able to document numerous finds since 1988. The outline of the Roman city map is also known; the position of today's Wiener Strasse / Heßstrasse coincides with that of the Roman main street. The history of the Roman city is also roughly known.

During the second half of the 4th century, the inhabited area of the Roman city began to shrink. In the first half of the 5th century, most of the population left the city, possibly to find shelter in safer settlements on the Danube. The latest evidence of ancient life - a grave with a bowl - dates back to around 450. Aelium Cetium was therefore abandoned and settlement was interrupted for centuries in its place.

Settlement interruption

From the 5th to the 8th century, the later city of St. Pölten was uninhabited, but there are finds from the time of the Great Migration in nearby villages that are now incorporated . In the northern villages of Pottenbrunn and Unterradlberg, for example, between 500 and 550 settlements of small Langobard clans have been documented. The reason why the Germanic peoples left the decaying remains of the empty Roman city unused could have been their literary city shyness.

Foundation of St. Pöltens

Political history: Avar Empire and Frankish Empire

The prerequisite for the development of a settlement in the area of today's St. Pölten were political upheavals on a larger scale. Since the end of the 6th century, the immigrant Avars (together with the ancestral population) had been living in Central Europe , and the area of today's Lower Austria was also part of their empire before St. Pölten was founded. To the west of the Avar Empire was the Frankish Empire , which expanded under Charlemagne , also to the east. After there had already been armed conflicts between Avars and troops fighting for the Frankish Empire, Charles's first major campaign against the Avars took place in 791 . As a result, the Avars were defeated and even disappeared completely from history around 822 - at least as an independent people. The rulership by the Franconian Empire and the Christian church organization began in Lower Austria in 791 and in the following years. At that time, new settlements and monasteries emerged in Lower Austria, including probably St. Pölten, which has been inhabited since then.

The foundation

Many of the questions about the founding of St. Pölten are still unanswered according to the current state of research. It is certain that in the early Middle Ages there was both a monastery (the Hippolytus Monastery ) and a secular settlement in the area of the city center, which is now surrounded by the promenades . The archaeologically proven monastery was built by the Tegernsee monastery possibly after the Avar campaigns of Charlemagne (from 791), but at the latest around 850. The settlement has not yet been proven archaeologically ; The name, time of origin and location within the old town are disputed in research. Possibly it is identical with the place Treisma , which is mentioned several times in texts of the 9th century. In any case, a document from the year 976 speaks of the “Treisma” settlement at the “Monastery of St. Hippolytus”.

The city got its name from this monastery: "Pölten" is a Germanized form of the male given name "Hippolyt". The namesake of the city was the western church father and first antipope in history, Hippolytus of Rome (approx. 170-230).

The medieval history of St. Pölten probably began at the end of the 8th century with the construction of the Hippolyt monastery, which was located where the diocese of St. Pölten is today. According to the most common thesis, the early medieval place was located west of the Hippolytkloster on the ground which is now surrounded by Klostergasse, Grenzgasse, Domgasse and Kremser Gasse. Presumably it was a typical early medieval cluster and alley village. What is remarkable is the fact that in early St. Pölten there were probably two manorial domains in a small area: the Hippolytkloster belonged to the Tegernsee monastery, the Treisma settlement belonged to Passau .

Hippolytus Monastery

The St. Pölten Hippolytkloster in the northeast corner area of the former Roman city was built by the Bavarian monastery Tegernsee probably after 791. Since Charlemagne gave the territories conquered by the Avars to participants in the campaigns, it can be assumed that the Bavarian monastery Tegernsee came to its possessions in the St. Pölten area in this way.

The Hippolytus monastery was a Benedictine monastery and equipped with relics of the eponymous Hippolytus of Rome . So far, only a few structural remains of the Hippolytus Monastery have been found, but none from the pre-Romanesque period (before 1000). Ceramic fragments exhibited in today's Diocesan Museum, on the other hand, were found from the time the monastery was founded, in 1949 in the Kapitelgarten and 1951 and 1988 in the Kapitelgarten of today's diocese building in St. Pölten. Early medieval accounts mentioning the Hippolytus Monastery date from the 10th century. It is disputed whether the founding story in the Historia Canoniae Sand-Hippolytanae published in 1779 , according to which the two brothers Adalbert and Otkar founded the monastery, is true. In any case, Adalbert was abbot of Tegernsee from 765 to 803/4.

The place Treisma

In addition to the founding of the monastery, medieval texts also speak of a place called Treisma , which was not owned by Tegernsee, but by Passau . Research largely agrees that Treisma was the old name of the emerging St. Pölten, i.e. that at least in some of the texts in question, Treisma stands for St. Pölten.

The place Treisma was first mentioned in passing in a document for the year 799. In other mentions of the two following centuries, Passau possessions in Treisma are mentioned, which the bishops of Passau had secular rulers confirm in documents. In the second quarter of the 9th century, Tegernsee became a commander of the Diocese of Passau, which is why Bishop Pilgrim von Passau had Emperor Otto II confirm the possession of the St. Pölten Hippolytkloster in 976 .

Urban development

The Hippolytus monastery and the settlement separated from it were the nucleus of the medieval city. The development of St. Pölten's old town, which was surrounded in the High Middle Ages by the St. Pölten city wall, which was built around 1253 to 1286 , did not come to an end until 1367. Around this time, the area within the city wall was largely built up for the first time. Despite the long pause in settlement after the fall of the Roman city, the medieval urban development was strongly influenced by the Aelium Cetium complex. Not only that the dilapidated ruins were removed and their material used for construction, some of the old Roman buildings - for example on Domplatz - have been adapted and continued to be used. Some of the streets and squares that were newly laid out in the Middle Ages are also exactly where Roman streets and squares used to be.

High Middle Ages

St. Pölten was granted market rights around 1050. St. Pölten was elevated to a town in 1159 by Bishop Konrad von Passau . This makes it the oldest city in Austria , ahead of Enns and Vienna , but this is not undisputed. Today's Raizinsberg desert is mentioned in 1180.

Late Middle Ages

In the 13th century, the city was expanded as planned by a western part with the broad market (today Rathausplatz) and surrounded by a city wall. The quarter around the monastery was subordinated to the provost of the monastery, while the Passau part was given municipal administration with a judge and council.

The first news about Jews in St. Pölten comes from around 1300 . In 1306 and 1338 there were pogroms against St. Pölten Jews.

In 1338 a new town charter was granted by Bishop Albrecht II of Passau .

Until the end of the Middle Ages, St. Pölten remained Passau and only became a princely rule as a result of the town being pledged to King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary. In 1481, Bishop Friedrich Mauerkircher pledged the city to the Hungarian king, who made it one of his most important bases in Lower Austria in the fight against Emperor Friedrich III. made and greatly encouraged. In 1487 he awarded St. Pölten a letter of arms, shortly afterwards extensive toll and transport privileges. After the expulsion of the Hungarian king, Maximilian I claimed the city as spoils of war in the Peace of Pressburg in 1491 and did not give up his claims against the actual city lord, the Bishop of Passau. As a sovereign city, St. Pölten was represented in the state parliament and received a new coat of arms from Ferdinand I in 1538 , which expressed his new position.

Reformation and Counter Reformation

As early as 1522, the St. Pölten citizen Philipp Hueter had to appear before the council and the city judge as a supporter of the Reformation . Dealers, especially booksellers, had brought the new ideas from southern Germany to St. Pölten. But it was not until after 1550 that the Lower Austrian Landtag was shaped by the Protestant faith after the reformer Martin Luther , and so the Lower Austrian cities tried to defend their religious freedom against the Catholic Habsburg ruler and Emperor Maximilian II . Against the will of the Canons' monastery, the council of St. Pölten, led by councilor and city judge Martin Zandt, got the former Premonstratensian and Lutheran pastor Conrad Lindemayer to come to the parish church of Our Lady in 1559 . The preacher Sigmund Süß was appointed to the parish church in 1568. In 1569 St. Pölten had become a predominantly Protestant town. A German citizens 'school, which all residents could attend, was founded, as was a new “citizens' hospital”.

The Counter-Reformation had already started elsewhere when Georg Huber became the new canon of the monastery in 1569, who was completely against the Evangelicals. He resigned the preacher Suss, so that the council took over his wages. Then Huber had the parish church blocked. The church was forcibly opened under the leadership of Zandt. This conflict came before the sovereign Emperor Maximilian, who found the councils involved guilty, and Preacher Suss had to leave the city. The supporters of the Reformation now attended the Protestant church service in the manor house of St. Pölten's Franz von Prösing or in chapels and churches of aristocratic landowners such as Schloss Kreisbach in Wilhelmsburg. In 1578 an imperial decree forbade the city council from all innovations in religion, closed the city schools and declared the Corpus Christi procession binding for everyone. The visible evangelical life disappeared from the city by 1623. On March 20, 1625, houses were searched and 220 " heretical " books were confiscated.

Only in 1781 were Protestant churches allowed again under Emperor Joseph II with the Tolerance Patent . From 1856, the Lutheran preacher of the Oldenburg Imperial Count Gustav Adolf Bentinck led Protestant services in Fridau Castle near Ober-Grafendorf . In the city itself, Protestant services were held again from 1877 onwards, and in 1892 a Protestant church was built for the community, which had since grown to 170 people. The Baudissin-Zinzendorf family from Wasserburg Castle supported the construction.

Early modern age

The St. Pölten city wall proved to be effective protection against the Turks in the course of the First Austrian Turkish War in 1529 and the Great Turkish War in 1683.

St. Pölten experienced a particular heyday in the 17th and 18th centuries. Jakob Prandtauer and Joseph Munggenast made the city a center of baroque architecture, which stood almost on a par with the school grouped around the Viennese court. At that time, the cityscape with the cathedral, the Carmelite Church, the Institute of the English Misses, the town hall facade and several aristocratic palaces received its charming baroque appearance. Renowned artists such as Daniel Gran , Bartolomeo Altomonte and Tobias Pock worked on the cathedral church (1722–1750) . In the course of the Catholic reform, new monasteries were founded, so that around 1770 the town of only 29 hectares had a total of six religious settlements, of which, as a result of the abolition of the monastery under Emperor Joseph II, only the Institute of the English Fräulein (since 1706) and the Franciscan monastery (today Philosophical-Theological University) remained. The Josephine reforms made St. Pölten an ecclesiastical center: in 1785 the diocese of Wiener Neustadt was transferred to St. Pölten and the previously dissolved canon monastery was designated as the bishopric. The first bishop was Johann Heinrich von Kerens until 1792 .

After the medieval pogroms, Jews did not return to St. Pölten (as traders) until the 17th century. In 1863, the St. Pölten religious community with around 800 members was founded. About half of the members lived in the city.

After the march on St. Pölten , Napoleon I entered without a fight on November 11, 1805 and plundered the city. The city was also occupied by French troops in 1809.

Industrialization and first half of the 20th century

St. Pölten in the Franziszeischen Cadastre , 1821

St. Pölten and the surrounding area in the Franziszeische Landesaufnahme , between 1806 and 1869

With the opening of the Kaiserin-Elisabeth-Bahn in 1858, later the Westbahn , and the later construction of additional branch lines, St. Pölten developed into an industrial city. Since the 18th century, in the course of industrialization, smaller businesses began to settle, including hammer mills, paper mills, cloth makers and a calico factory. After 1903, important large companies were founded, such as the Salzer paper factory , the Voith machine factory , the 1st Austrian Glanzstoff-Fabrik AG and the railway workshops . The population rose sharply (1848: 4500, 1880: 10,000, 1922: almost 22,000), and new settlements were built in the villages of Viehofen, Ober- and Unterwagram, Teufelhof and Spratzern, which were incorporated in 1922.

- St. Pölten emergency money from 1920

With the granting of its own statute in 1922, the new economic importance of St. Pölten was taken into account.

The economic crisis of 1930 turned the hope area into a disaster area with thousands of unemployed.

After the collapse of the KuK monarchy in 1918, St. Pölten was affected by the political turmoil in Austria after the war, such as the civil war in 1934 and the annexation of Austria in 1938.

National Socialism and World War II 1938–1945

Seizure of power

On March 11, 1938, there were pro-Austria rallies in St. Pölten and the armed forces were preparing against the invasion of German troops. In the evening, after the resignation of the Austrian Chancellor Schuschnigg , thousands of people from St. Pölten were celebrating with swastika flags in the streets. The St. Pölten National Socialists gathered, appointed Hans Doblhofer as district leader, Franz Pfister as district leader and Franz Hörhann as mayor. The NSDAP and SA occupied the town hall before midnight . One day later the armed forces invading Austria came to St. Pölten on their way to Vienna, where they were received with jubilation. On March 14, the day before his speech at Heldenplatz , Adolf Hitler visited St. Pölten and had lunch with Heinrich Himmler , Wilhelm Keitel and Martin Bormann at the Hotel Pittner.

Groß-St. Pölten

Although Krems became the district capital of Lower Austria, which had been renamed " Niederdonau ", St. Pölten was supposed to become a "Gauwirtschaftsstadt" according to Nazi planners because it had industry, rail connections and large available areas. One spoke of “Groß-St. Pölten ”and incorporated numerous localities into the city. Under National Socialist rule, not only was the huge air force base built in nearby Markersdorf , but also the “Spratzern Camp” (later the Kopal barracks ) and other army facilities. Furthermore, the construction of a Reichsautobahn from Salzburg via St. Pölten to Vienna began and the railway network was expanded. Residential buildings such as the "Volkswohnhausanlage" (also: Südtirolersiedlung) built from 1938 to 1940 were built. During the Nazi era , the Rathausplatz was called “ Adolf-Hitler-Platz ”, the new building area was called “Platz der SA”.

Persecution of the Jews

In 1938 the Jewish community in St. Pölten had 1200 members, 400 of whom lived in the city itself. Organizations like the SD soon began to arrest Jews, there were evictions, professional bans (for doctors, veterinarians, pharmacists and lawyers), verbal abuse and Humiliation. During the November pogrom of 1938 on the night of November 9th, around 350 uniformed men and civilians devastated the St. Pölten synagogue and shops; numerous Jewish citizens were arrested. From May 1940 there were hardly any Jews left in St. Pölten, and those who had not been arrested and could not emigrate were made to register in Vienna. On October 7, 1941, the mayor announced that St. Pölten was free of Jews and Gypsies. Three cases are known in which Jews managed to survive undetected in St. Pölten until 1945.

In financial terms, the state, the municipality and private individuals benefited from the expulsion of the Jews. Numerous shops, businesses such as the Schüller factory, apartments and other property were expropriated . The synagogue served as a camp for Soviet prisoners of war and the SA Standard 21, one Jewish cemetery was completely destroyed, and another, which still exists today, was left neglected. The number of mass murders in the concentration camps of the Third Reich rose in particular from 1941 onwards, at least 300 of the 1200 members of the St. Pölten religious community have been shown to have been murdered, and almost none returned to St. Pölten after the war.

Armaments factories

In the course of the war, St. Pölten also saw a large degree of industrial production being converted to armaments. Numerous companies, including the largest, increased their production and employee numbers considerably. Since not only the Jews had disappeared from the city, but also large parts of the rest of the male population had been drafted into the Wehrmacht, not only women but also forced laborers ( prisoners of war , prisoners) began to be deployed in St. Pölten on a large scale . This happened in almost all of the city's businesses, and there were at least 400 deaths or murders - as in the camp for Jews deported from Hungary in the Viehofner Au.

resistance

The resistance against the Nazi regime in St. Pölten assumed significant proportions in comparison with Austria, even if it had no political or military concrete successes. The Catholic resistance was mainly limited to illegal religious instruction, the Jehovah's Witnesses refused to use the weapon and towards the end of the war the couple Trauttmansdorff organized a non-partisan resistance group ( Kirchl-Trauttmansdorff resistance group ). The 400 or so conspirators included mainly members of the upper class; The aim was to hand over the city to the Soviet troops without a fight. However, the group was infiltrated by a V-Person and betrayed. On April 13, 1945, twelve members were sentenced to death and shot in Hammerpark , where a memorial today commemorates them. Most important were the resistance groups that emerged from the already strong labor movement and largely originated from the illegal KPÖ and its environment.

In the larger businesses in the city (railway workshops, post offices, Voith, Glanzstoff, Salzer), groups were organized that printed propaganda material against the regime and carried out strikes and acts of sabotage (explosions, damage to machines, theft). Following persecution by the Gestapo , there were 123 court cases and 28 death sentences against railway workers in 1941, 11 Voith employees were also executed and 37 of the Post Office were arrested.

war

In June 1944 the first air raids by Allied bomber groups took place. The main destination was the train station. The heaviest bombings took place at Easter 1945. 591 people died, 142 of the 4,260 houses were completely destroyed, 233 more than half, and a further 2701 light to medium. 3,500 people were homeless and large parts of the infrastructure (such as gas and water supply) were hit. Protection was provided by numerous bunkers that were built at the time or by fleeing to the countryside.

In the early months of 1945, St. Pölten Nazi leaders were still talking about fighting to the last man, so prisoners, deserters and resistance members were killed right up to the end. On April 14, 1945 the Red Army attacked St. Pölten. After the rapid capture of the city on April 15, the front ran for three weeks in the west of St. Pölten. During the conquest, around 600 civilians died, 24,000 fled and only around 8,000 people remained in the city. According to their own statement, the Soviet troops had tried to do as little damage as possible to the city; which has also succeeded comparatively well. The contact between the St. Pölten and the Soviet soldiers is said to have been friendly on the one hand - after all, it was about liberation from the Nazi regime and the end of the war - on the other hand, it was overshadowed, especially at the beginning, by food lootings and numerous rapes. After the fighting ended, large parts of the Red Army stationed in the city withdrew.

Overall, the war destroyed or severely damaged 39% of St. Pölten's buildings.

Soviet occupation and reconstruction 1945–1955

Political reorganization

On April 16, 1945, the 24-year-old iron goods dealer Günther Benedikt , who came from a Jewish family, was appointed provisional mayor by the Soviet troops, but only for a short time. Franz Käfer , stoker in the Glanzstoff and former commandant of the Wagram Schutzbund, switched from the Social Democrats to the KPÖ in 1935. On the orders of the Russian city commander Chomaiko, he became mayor of St. Pöltens on May 13, 1945 and remained so for the first five years of the city's rebuilding. Ten representatives of the KPÖ, 10 of the SPÖ and 6 of the ÖVP sat on the municipal council. For a new beginning, Käfer called for people to work together and put personal and political things to one side. The local council minutes of the first post-war years give the general impression of an objective and constructive working atmosphere and it was only towards the end of the reconstruction that the party differences became more noticeable again.

In the state elections in 1945, the St. Pölten SPÖ clearly won (SPÖ: 22 seats, ÖVP: 15, KPÖ: 6). Käfer resigned, but remained mayor until the first municipal council elections in 1950 due to the intervention of the Soviet commander . With the withdrawal of the Soviet troops from Lower Austria, the influence of the KPÖ also decreased significantly. The municipal council election results since 1960 show a steady decline from 13.2% to 0.8% in 2001 . Since then, the KPÖ has not competed in St. Pölten. St. Pölten's mayor was the socialist Wilhelm Steingötter from 1950 to 1960 .

Distress, Reconstruction and USIA

After the end of the war there was initially bitter hardship and homelessness. In the following three years rubble was cleared and the train station, important utilities and some bridges across the Traisen were rebuilt. Only then did the community begin to rebuild houses, schools, streets, canals etc. on a larger scale. Most of the new apartments within a year, namely 315, were built in 1952.

The economic situation was marked by the lack of goods; there was little to buy and when there was, consumer goods were difficult to access due to the high price increases. Clothing, furniture and, above all, groceries (some groceries up until the 1950s) were available in exchange for purchase vouchers that were issued by the alumni depending on occupation, age, etc. People "muddled through" and a black market established itself which lasted until around 1950. The worst hardship was overcome in 1953 even for those with lower incomes, but one could not speak of prosperity for a long time. Apartment rents were low in the years after the war. The reason for this was rental laws, but also the poor condition of the inhabited barracks (for example in Herzogenburgerstrasse) and apartment buildings .

After the end of the war, the Red Army began dismantling German property (especially machines in large companies such as Voith and Glanzstoff), but stopped this and organized the resumption of production when it became clear that the occupation would last longer. Since June 27, 1946, all companies that were considered German property were combined in the USIA group. The few companies that made profits like Voith had to deliver them as reparations to the Soviet Union. The USIA companies were a stability factor for the labor market, but the unemployment rate in St. Pölten rose to over nine percent in 1953.

End of the occupation

On February 10, 1955, numerous incorporations from the Nazi era were withdrawn again by a resolution of the state parliament, mostly after popular votes. The municipal area sank to 43.23 km² with 38,563 inhabitants. St. Pölten was then the eighth largest city in Austria and remained the largest in Lower Austria.

The State Treaty was signed in May 1955, the Soviet troops began to withdraw from St. Pölten in August 1955, and the last soldiers left the city on September 13th. If the parts of Austria occupied by the Soviet Union were economically disadvantaged, the USIA operations, which were handed over to the Austrian federal government in August 1955, then had outstanding loans and had to provide material assets to the Soviet Union for six years. The federal government, in turn, should return the 280 Lower Austrian USIA companies to their original owners.

Development after 1955

In 1972 the city crossed the 50,000-inhabitant limit for the first time through the incorporation of Ochsenburg, Pottenbrunn and St. Georgen, among others.

Capital issue

St. Pölten became the provincial capital of Lower Austria with a resolution of July 10, 1986. St. Pölten had previously opposed Krems (29%), Baden (8%), Tulln with 45% in a referendum on March 1 and 2, 1986 (5%) and Wiener Neustadt (4%) enforced. Since 1997, after the regional authorities moved out of Vienna and the country house quarter was built , St. Pölten has also been the seat of the Lower Austrian regional government .

On July 9, 1999, the city received the Council of Europe plaque of honor for its services to international activities, city partnerships and as the leader of the “Cooperation Network of European Medium-Sized Cities” . During the session, the Council of Europe on 26 April 2001 St. Pölten was European Prize awarded. In 2002 the Lower Austria Museum opened .

Kurt Krenn , the heavily controversial Bishop of St. Pölten, who has been in office since 1991, submitted his resignation on September 20, 2004 after incidents of abuse in the seminary . Klaus Küng was appointed 17th bishop of the diocese of St. Pölten .

In St. Pölten there is also the Evangelical Superintendenty A. B. Lower Austria , which was moved here from Bad Vöslau in 1998 .

A gas explosion killed five people in June 2010 and caused extensive property damage.

politics

Municipal council and city senate

(+ 2.2 % p )

(-5.0 % p )

(+ 4.0 % p )

(-2.2 % p )

(+ 0.9 % p )

The municipal council consists of 42 members. Since the 2016 municipal council elections , 26 seats have been held by the SPÖ , nine by the ÖVP , six by the FPÖ and one by the Greens .

The city senate consists of the first and second vice mayors as well as eleven other members, the members of the city senate are also members of the municipal council. Since the 2016 municipal council election , it has consisted of eight members of the SPÖ , three of the ÖVP and two of the FPÖ .

mayor

The office of mayor is Matthias Stadler (SPÖ), 1st vice mayor has been Harald Ludwig (SPÖ) since February 2020, and 2nd vice mayor has been Matthias Adl (ÖVP) since 2011.

Mayor Matthias Stadler

Coats of arms, colors and seals

| Blazon : “ Split by silver and blue ; in front a red bar , behind a soaring, silver, red-tongued and gold-armored wolf . " | |

| Justification of the coat of arms: The coat of arms awarded to the city of St. Pölten by King Ferdinand I on November 3, 1538 consists of two parts. The heraldic right (left from the observer) shows the inverted Austrian shield as a sign of the sovereign affiliation of the city. The heraldic left part with the upright wolf is an expression of the origin from the property of the Diocese of Passau . The pedum (bishop's staff ) that wolf held in its paws in the 15th century has disappeared. |

The city's colors are red-yellow. The town's seal shows the town's coat of arms with the inscription "State Capital St. Pölten". The official seal of the magistrate shows the coat of arms and the inscription "Magistrat der Stadt St. Pölten".

The city has used various logos in publications since the 1960s. These reflect the developments in the city. This was the text of the State Capital St. Pölten logo, used from 1986 , the current one shows the text st next to the stylized stars of the European flag . pölten in the middle of europe .

Town twinning

-

Altoona , Pennsylvania , (United States), since 2000

Altoona , Pennsylvania , (United States), since 2000 -

Brno (Czech Republic), since 1990

Brno (Czech Republic), since 1990 -

Clichy (France), since 1968

Clichy (France), since 1968 -

Heidenheim (Germany), since 1967

Heidenheim (Germany), since 1967 -

Kurashiki (Japan), since 1957

Kurashiki (Japan), since 1957 -

Wuhan (People's Republic of China), since 2005

Wuhan (People's Republic of China), since 2005

E-government

For citizens who have their main place of residence in St. Pölten, the city administration offers electronic forms that save administrative procedures. The online forms can be sent directly to the relevant municipal office. The forms are based on the AFORMSOLUTION form solution from the Austrian IT company aforms2web and include a. Funding applications or various applications.

population

Population development

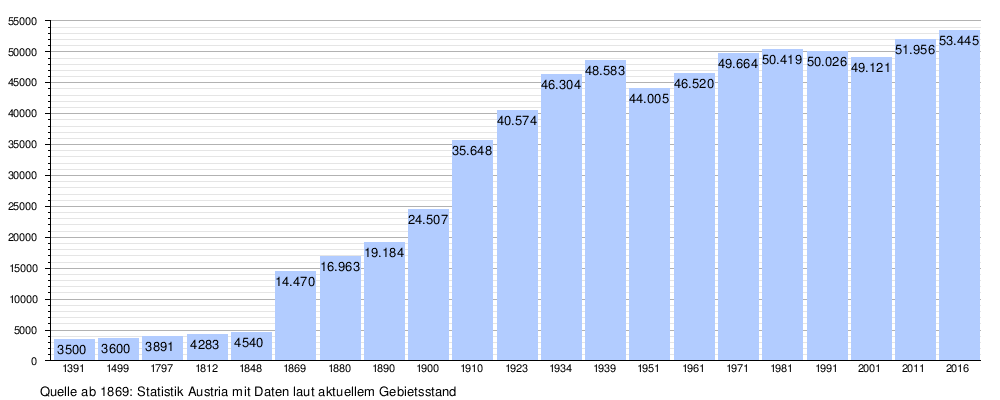

Statistics Austria has been collecting data since 1869 .

society

Personalities

economy

In 2011 the city of St. Pölten received 178,071,808.34 euros and spent exactly the same amount.

Workplaces and employees

| year | Workplaces | Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 2.131 | 30,544 |

| 2001 | 2.711 | 40,041 |

| 2006 | 3,764 | - |

As of May 15, 2001, 40,041 people were working at 2711 workplaces in St. Pölten . Of these, the 23 largest workplaces each employed 199 people , the 1676 smallest 0 to 4 employees. Of the 23 largest workplaces, 6 were in the manufacturing sector and 17 in the service sector .

The three largest workplaces in 2001 each employed over 999 people (including the hospital and government district ).

commuter

In 2001, 16,347 people from St. Pölten worked in St. Pölten, and 6,035 commuted outside to work. Conversely, since there are far more jobs than those in employment in St. Pölten, 24,866 people (around 60% of all those in employment in St. Pölten) commuted from outside to St. Pölten for work. This results in 41,213 employed people in St. Pölten in 2001.

media

Some media companies have their headquarters or administration in St. Pölten. These include MFG-Das Magazin, a monthly independent print medium , @cetera , Campus Radio 94.4 , the university's radio station, and, until 2012, HiT FM , another radio station. There is also a studio of the Austrian Broadcasting Corporation (ORF) for Lower Austria, the regional television station N1 and the private station P3tv . The editorial offices for the Lower Austria area of the Austria Press Agency (APA), Wiener Kurier and Der Presse are also based here.

The Niederösterreichisches Pressehaus in St. Pölten publishes the Niederösterreichische Nachrichten (NÖN), the Burgenländische Volkszeitung (BVZ), the NÖ-Rundschau, our free newspaper, the Neue Stadtzeitung and the Landeshauptstadt-Zeitung .

Established businesses

Production plants

The city is supplied with district heating by Fernwärme St. Pölten GmbH . This is a subsidiary of the city of St. Pölten and EVN. Since 2009, two thirds of the heat has been supplied by EVN Wärme via the 31 km long district heating transmission line from the Dürnrohr power plant . Almost all of the city's buildings connected to the district heating network are supplied with this heat.

Voith St. Pölten has existed since 1904 . Today's Voith Austria Holding , headquartered in St. Pölten, primarily manufactures paper machines , turbines and turbo gears . In 1961 Voith St. Pölten had 3,031 employees, in 2012 it was only 870 with annual sales of 271.2 million euros. In February 2015 it was announced that Voith-Paper is closing the St. Pölten site and cutting 150 jobs.

The 1986 founded and wholly owned by the Norwegian ON Sunde AS located Sunpor Plastic GmbH operates two production sites in the districts Radlberg and Stattersdorf. In particular, the company supplies manufacturers of thermal insulation boards for building insulation, had 160 employees in 2009 and a turnover of 140 million euros.

Unterradlberg since 1970 location of the Egger Group , the chipboard (2014: 392 employees), which Radlberger beverage manufacturing and in a brewery the "Egger Bier".

Paper has been produced at today's paper factory in Stattersdorf since 1579, and has been owned by the Salzer family (today Salzer Papier GmbH) since 1798 .

In the Pottenbrunn district there is a plant of the Swiss company Geberit AG. There are sanitary-engineering of products manufactured, among other things for showers and toilets. In 2012 the site had over 420 employees.

The ÖBB main workshop in St. Pölten , which has been in operation since 1907, employed over 1,500 workers at the end of the 1920s; in 2011 it was only 576.

Trading companies

Kika Möbelhandelsgesellschaft mbH , founded in 1973, has been owned by the Koch family ever since. The company headquarters, a furniture store opened in 1977 and a warehouse (Spratzern district) of the pan-European furniture retailer, which became part of the SIGNA Group in 2018, are located in St. Pölten.

Rudolf Leiner GmbH , which is owned by the Leiner family and founded in 1910, has had its company headquarters and a branch in St. Pölten since then. The company's warehouse is located in the Spratzern district.

One of the seven large Austrian warehouses of the Austrian retail chain SPAR Austria is located in the Spratzern district .

|

Baumarkt Nadlinger Handelsges.mbH, founded in 1924 and still run as a family business today, has its headquarters in the Spratzern district, where a Hagebaumarkt and building materials wholesalers are operated. In 2015, the former Baumax location in the Viehofen district was taken over, which has been run as "Hagebaumarkt St.Pölten Nord" since 2016.

Other companies

- Klenk & Meder GmbH (electrical engineering and electrical appliance sales, founded in 1968 in St. Georgen, company headquarters in Spratzern since 1972, 700 employees)

- Niederösterreichisches Pressehaus Druck- und Verlagsgesellschaft mbH (2005: 484 employees and 100 million euros in sales)

- Salesianer Miettex (in Spratzern there is a laundry and a warehouse of the Viennese family company that operates across Europe)

- Schubert & Franzke GmbH (publisher for city and town maps, based in St. Pölten, 60 employees)

- Rosenberger (Rosenberger Restaurant GmbH, ROSENBERGER FUELS GMBH and Rosenberger Tankstellen GmbH)

- Strabag has a location in St. Pölten .

Former companies

From the middle of the 19th century onwards, numerous industrial companies emerged in St. Pölten, many of which have not survived to this day.

- The largest industrial companies in today's urban area were Glanzstoff Austria (1906–2008) and Harlander Coats (1859–1991).

- Even before the Second World War included

- the Winger Brewery (1589–1931) and factories such as

- the k. k. priv. mirror factory (1804-1858),

- the lace and bobbinet and curtain factory F. Austin (1866–1930) and

- the St. Pölten soft iron and steel foundry Leopold Gasser (1870–1930).

trafficmobilityIn St. Pölten, 44 percent of everyday trips are car-free (as of 2016). That is the seventh place in comparison with the other state capitals. There are 565 cars per thousand inhabitants in the city. Street |

|

|

The city lies at the intersection of the West Autobahn A 1 with the Krems expressway S 33 and is crossed by the Wiener Straße B 1. The junction of the currently planned and hotly debated Traisental expressway S 34 is to be in St. Pölten.

Major roads

- West Autobahn A 1 from Vienna to Salzburg

- Krems expressway S 33 from St. Pölten to Krems

- Traisental expressway S 34 from St. Pölten to Wilhelmsburg (in planning)

-

Wiener Strasse B 1

- Wiener Straße B 1a, St. Pölten (B 1) –St. Pölten (S 33)

- Mariazeller Straße B 20, from St. Pöltner Europaplatz to Kapfenberg

- Pielachtal Straße B 39, from St. Pölten to Winterbach

Parking garages

There are ten multi-storey car parks near the city center with a total of around 3900 parking spaces.

Public transport

railroad

There are twelve train stations in St. Pölten, of which St. Pölten's main train station is the largest. There are the following railway lines with at least passenger traffic:

- Westbahn line (with a journey time of 25 minutes to Vienna)

- Terminus of the Leobersdorfer Bahn

- Terminus of the Mariazeller Bahn

- Terminal of the Tullnerfelder Bahn to Krems and Tulln

Regional bus

- The junction of the Wieselbus lines, which connect the capital in a star shape with the various regions of Lower Austria, is the Wiesel bus terminal in the government district.

- Other regional bus routes run from the main train station.

Local transport

- Tram , historic; operated from 1911 to 1976, ( St. Pölten tram )

- Urban bus system "LUP", network of 13 lines

- free tourist train , connects the old town with the Landhausviertel

- Call shared taxi, a supplement to public transport at night, runs between all bus stops in the city for a fixed price

Bicycle traffic

Ten percent of inner-city traffic in St. Pölten is by bicycle. The existing route network is to be expanded and linked from 165 to 219 kilometers in the coming years. A mix of cycle paths, sidewalks and cycle paths, cycle lanes and multi-purpose lanes is planned. In 2005, the pedestrian zone in the city center was opened to cyclists.

St. Pölten is also the starting point for many cycle routes, mainly along the Traisental cycle path that extends from Mariazell to the Danube .

air traffic

The Völtendorf airfield is located on the area of the former garrison training area Völtendorf.

Public facilities

Agencies and public authorities

- Office of the Lower Austrian state government (since 1986 state capital)

- District Commission

- Lower Austria agricultural district authority

- Tax office

- Regional Court of St. Pölten

- District Court

- Land surveying office

- Labor market service

- Bar Association of Lower Austria

- District office of the Chamber of Commerce

- District office of the Chamber of Labor

- State Chamber of Agriculture

- District Chamber of Farmers

- Lower Austrian Regional Health Insurance Fund (main office)

- Lower Austrian regional building authority III

Health and safety

health

St. Pölten is home to the St. Pölten University Hospital with 3,100 employees and 1,100 beds as well as an army hospital, 225 doctors and ten pharmacies. The rescue service is maintained by three offices of the Samaritan Association as well as one each of the Red Cross and a private provider of interhospital transfers. One of the four emergency control centers of 144 Emergency Numbers Lower Austria (formerly LEBIG) in Lower Austria is located in the state capital .

St. Pölten is the location of the only crematorium in Lower Austria

Nursing homes

- Stadtwald retirement home

- Lower Austria State Nursing Home St. Pölten (LPH)

- Nursing home Pottenbrunn

- House St. Elisabeth: The nursing home operated by Caritas St. Pölten offers temporary and permanent living for a total of 131 people.

police

The State Police Department of Lower Austria acts as the security authority for the city . Subordinate to you as the station of the guard for the urban area is the St. Pölten City Police Command .

fire Department

The area alarm center of the volunteer fire brigades in St. Pölten and the districts of St. Pölten-Land and Lilienfeld is located in the city. In contrast to most other state capitals, St. Pölten does not have a professional fire brigade , but currently 14 volunteer fire brigades and 10 company fire brigades .

Educational institutions

Kindergartens, schools and universities

- In 2013 there were 24 kindergartens , in addition to a few private ones, St. Pölten had twelve public elementary schools and three special schools .

- There were also five new middle schools and one private secondary school as well as a polytechnic school in the city area .

- After completing compulsory schooling , four grammar schools , one vocational school (with 15 apprenticeships offered), the higher technical federal teaching and research institute St. Pölten , a commercial academy , a higher educational institute for economic professions , an HBLA , an HLA and the federal institute for kindergarten and social pedagogy St. Pölten can be visited.

- In addition to the St. Pölten University of Applied Sciences, there is the private university of the creative industries , the Bertha von Suttner private university , a philosophical-theological university and a university of applied sciences for mechanical engineering and construction, which can be completed as part of a part-time distance learning course .

- The St. Hippolyt Education Center is an education center of the diocese of St. Pölten .

Further educational institutions are the VHS St. Pölten, the economic development institute of the Lower Austrian Chamber of Commerce and the Lower Austria Municipal Academy . The city is home to the St. Pölten Security Executive Education Center (BZS) of the Security Academy . The Lower Austrian State Academy was dissolved in 2017.

Libraries

There are five larger public libraries in St. Pölten . The city library St. Pölten decreed in 2002 more than 100,000 media, the other four offer especially scientific literature, the Lower Austrian library with 488,500 title records (2012) is the most comprehensive library of St. Pölten. Scientific specialist libraries are the Federal Educational Library at the State School Council for Lower Austria with 150,000 volumes (2013), the library of the Philosophical-Theological University of St. Pölten with 100,000 volumes (2013) and the library of the University of Applied Sciences St. Pölten with 26,000 media (2013).

Leisure and sports facilities

Bathing and swimming facilities

- Aquacity , indoor swimming pool

- citysplash, outdoor swimming pool

- Ratzersdorfer See , a swimming lake with nudism , beach volleyball and mini golf

- Viehofner Seen , 53 ha total area, half of the area consists of the water areas of the large and small lake

Sports clubs and sports facilities

In addition to various fitness studios, there are many sports clubs in St. Pölten, including:

- American Football Club - St. Pölten Invaders

- Badminton club

- Soccer - SKN St. Pölten , FC Sturm 19 St. Pölten and SC St. Pölten . The FC Sturm 19 is known for the later Rapid player Franz "Bimbo" Binder .

- St. Pölten Golf Club

- Handball Union St. Pölten - Prandtauerhalle

- Sports Aviation Club St. Pölten

There is also a main office of the Lower Austrian State Sports School in St. Pölten .

tennis

Every year in the third week of May an ATP tournament took place in St. Pölten , which was moved to Pörtschach in 2006 .

Triathlon

In May 2007–2019 the Ironman 70.3 Austria took place - a triathlon competition over half the Ironman distance (1.9 km swimming, 90 km cycling and 21.1 km running). From 2020 the competition will be held as a challenge race .

Culture and sights

Sacred buildings

- Cathedral of the Assumption and diocese building: Former Romanesque basilica modified in baroque style by Jakob Prandtauer , Matthias Steinl and Joseph Munggenast . Frescoes and paintings a. by Daniel Gran , Thomas Friedrich Gedon , Bartolomeo Altomonte , Antonio Tassi and Tobias Pock . Romanesque rosary chapel. 77 m high Romanesque cathedral tower.

- Mary Ward School Center St. Pölten (formerly the Institute of the English Misses ): Institute building built by Jakob Prandtauer and his building school from 1707 with a baroque palace facade. Chapel room with frescoes by Paul Troger and Bartolomeo Altomonte, Lourdes grotto.

- Franciscan monastery with Franciscan church St. Pölten : Former Carmelite church with rococo facade . Inside four side altar pictures by Martin Johann Schmidt , the "Kremser Schmidt".

- Parish Church of St. Johannes Kapistran

- Parish church St. Pölten-St. Joseph

- Parish church of St. Georgen am Steinfelde

- Parish Church of Maria Lourdes

- Prandtauerkirche zur Maria vom Berge Karmel (former Carmelite church - built from 1707 onwards according to plans by the monastery architect Martin Witwer and building tour by Jakob Prandtauer) and Karmeliterhof

- Evangelical church and rectory

- Sacred Heart Church

- Chapel in the St. Hippolytus Education Center

- Chapel in the Kolping House

- Chapel in the former citizens' hospital ( old Catholic )

Profane monasteries and sacred buildings

- Former Franciscan monastery

- Former Carmelite Convent

- Former synagogue

government District

- Landhaus : Landtag and government building of the Lower Austrian provincial government by architect Ernst Hoffmann .

- Festspielhaus - concert hall and stage of international format with around 1,100 seats, architect Klaus Kada and opened in 1997.

- Shedhalle: Exhibition hall opened by Hans Hollein in 2002.

- Museum of Lower Austria : multimedia adventure museum in the fields of nature, art and regional studies, by architect Hans Hollein .

- State library and state archive of the architects Karin Bily, Paul Katzberger , Michael Loudon.

- Klangturm : Walk-in sound space in three floors with sound balls and a viewing platform from architect Ernst Hoffmann .

- Gate to the country house: Erected from 1993 to 1997 by Boris Podrecca .

- ORF Landesstudio: Established from 1994 to 1998, by Gustav Peichl .

Monumental buildings

- General public hospital with hospital chapel Maria, Heil der Kranken

- District Commission

- Federal Academy for Social Work

- Federal upper level secondary school

- Former Grand Hotel Pittner

- Central Station

- Hesserkaserne

- Higher technical federal teaching and research institute

- Jahnturnhalle

- Former Voith villa, now Kulturheim-Süd

- Regional court

- Regional judicial prison

- Lower Austrian regional health insurance fund

- Lower Austrian state retirement home

- Town hall : Landmark of the state capital on the town hall square . Several architectural styles can be recognized - Romanesque vaults, Gothic niches, Renaissance inscriptions, baroque facade and Renaissance tower by Joseph Munggenast . Mayor's room with baroque stucco ceiling .

- Schwaighof

- City halls

- City Theatre

More buildings

- Economic center of Lower Austria : South of the government quarter built according to the passive house style, houses the institutions of the state of Lower Austria that offer information and services for business people ( Ecoplus , RIZ start-up agency , Niederösterreich-Werbung , tecnet capital). Built by the architects Gschwandtner & Millbacher.

- State Theater Lower Austria : built in 1820 by Josef Schwerdfeger , in 1893 by Eugen Sehnal and in 1968 rebuilt and expanded. City theater until 2005. Since 2005 spoken theater.

- Riemerplatz: the only square in the city with a complete inventory of old houses from the Baroque period. Modern marble sculpture as the focus.

- Pharmacy Zum Goldenen Löwen : The oldest shop in St. Pölten since 1545, baroque facade by Joseph Munggenast.

- Herrenplatz: A square characterized by important baroque buildings with a central Marian column by Antonio Beduzzi . Daily market.

- Olbrich House : Nice Art Nouveau building in the city, built for Primary Hermann Stöhr by Joseph Olbrich , with mortar cut "Medicine" by Ernst Stöhr .

- Former synagogue : only Art Nouveau - Synagogue in Lower Austria. Rich decoration in ornamental forms from the Wiener Werkstätte.

- Ochsenburg Castle in the Ochsenburg district

- Pottenbrunn Castle , a renaissance castle in the Pottenbrunn district

- Viehofen Castle in the Viehofen district

- Wasserburg Castle , a baroque palace in the Pottenbrunn district

theatre

- State Theater of Lower Austria

- Stage in the courtyard

- Festspielhaus St. Pölten

Museums

- Workers museum

- Exhibition bridge

- Diocesan Museum St. Pölten

- historical Museum

- ART: WORK

- Museum in the courtyard

- Lower Austrian Documentation Center for Modern Art

- Museum Niederösterreich - visualization and exploration of the country's past and present in nature and culture: The House of Nature shows fish in aquariums , the House of History has replaced the former art exhibition since September 2017

- City Museum St. Pölten

Others

- Hollywood megaplex cinema center

- Cinema Cinema Paradiso

- City halls

- VAZ St. Pölten , event center and exhibition hall

- Youth culture hall frei.raum

- Capella incognita, baroque music ensemble from St. Pölten

- St. Pöltner Künstlerbund, artist association with exhibition space KUNST: WERK

- Belly sound , a cappella formation

- Kulturhaus Wagram

- Warehouse St. Pölten

- Market on Domplatz

- Hesserkaserne

- Copal barracks

- La Boom (nightspot)

- Cultural Association La Musique Et Sun - LAMES

Regular events

- Open air cinema on Rathausplatz - Cinema Paradiso group

- Capital Festival

- St. Pölten folk festival

- International culture & film festival

- Country party

- St. Pölten Festival Weeks with the St. Pölten Sound Meadow Baroque Festival

- St. Pöltner Höfefest

- NUKE Festival

- Holi Festival of Colors

- Frequency Festival

- Beatpatrol

- WISA St. Pölten

- Erotica erotic fair

- Melting pot

literature

history

- Heidemarie Bachhofer (Ed.): St. Pölten in the Middle Ages. Historical and archaeological search for traces. Diocesan archive St. Pölten, St. Pölten 2012, ISBN 978-3-901863-36-3 .

- Johann Frast: Historical and topographical representation of the parishes, monasteries, monasteries, charitable foundations and monuments in Archduke Austria - Sanct Pölten and the surrounding area; or: the Decanat Sanct Pölten. With two illustrations and a map of the dean's office. Anton Doll, Vienna 1828 (preview of: the first section of the seventh, the diocese of St. Pölten, second volume in the Google book search).

- Karl Gutkas : Becoming and essence of the city of St. Pölten. Lower Austrian Press House, St. Pölten (numerous editions).

- Emil Jaksch, Karl Gutkas: St. Pölten. Cultural and economic history. Bühn, Munich 1970.

- Thomas Karl: St. Pölten. A change through time. Sutton, Erfurt 2004 (illustrated book with historical photographs).

- Magistrate of the state capital St. Pölten (Ed.): St. Pölten 1945–1955. History (s) of a city (= St. Pölten Rainbow 2005. Cultural Yearbook of the State Capital St. Pölten ). St. Pölten 2005.

- Siegfried Nasko , Willibald Rosner (ed.): St. Pölten in the 20th century. History of a city. Residence, St. Pölten / Salzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7017-3155-8 .

- Ronald Risy: Municipium Aelium Cetium. 20 years of urban archeology 1988–2008. Dissertation Vienna 2009, urn : nbn: at: at-ubw: 1-29772.19323.431953-5 ( univie.ac.at ).

- Ronald Risy: Sant Ypoelten. Pen and city in the Middle Ages. In: Forum Archaeologiae . Volume 52/9, 2009 ( univie.ac.at ).

- Norbert Zand: History of the city of St. Pölten from 1900–1950 in the course of political, social and economic upheavals. Dissertation Vienna 1997, 2 volumes.

Music history

- Christian Fastl: St. Pölten. In: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon . Online edition, Vienna 2002 ff., ISBN 3-7001-3077-5 ; Print edition: Volume 5, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 2006, ISBN 3-7001-3067-8 .

architecture

- Otto Kapfinger , Michaela Steiner: St. Pölten new. The picture of the state capital = The New St. Pölten. Profile of the federal state capital. Springer, Vienna / New York 1997, ISBN 3-211-82954-7 .

- Thomas Karl u. a .: The art monuments of the city of St. Pölten and its incorporated localities. Berger, Horn 1999, ISBN 3-85028-310-0 .

Fiction

- Klaus Nüchtern : Looked at soberly. Small goulash in St. Pölten. 78 very useful columns with 5 exclusive, previously unpublished forewords. Falter-Verlag, Vienna 2003, ISBN 3-85439-306-7 .

- Hans Rankl (ed.): St. Pöltner stories. Residence, St. Pölten / Salzburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-7017-1536-7 .

Web links

- Pölten Entry on St. Pölten in the Austria Forum (in the AEIOU Austria Lexicon )

- 30201 - St. Pölten. Community data, Statistics Austria .

- Statutory city of St. Pölten Homepage of the state capital

- St. Pölten Tourismus Website of the St. Pölten tourist information office

- Niederösterreich Tourismus website with all visitor information

- The statutory city of St. Pölten in old views, exhibition catalog. (PDF; 8.9 MB) (No longer available online.) Formerly in the original ; accessed on March 23, 2018 (no mementos). ( Page no longer available , search in web archives )

Individual evidence

- ^ Federal Chancellery : St. Pöltner Stadtrecht 1977. In: gv.at. Legal information system of the Republic of Austria , archived from the original on October 20, 2013 ; accessed on December 15, 2016 .

- ↑ Statistics Austria - Population at the beginning of 2002–2020 by municipalities (area status 01/01/2020) .

- ↑ a b City portrait of the project “Reformation cities of Europe”: Reformation city of St. Pölten. Austria. Evangelical in Lower Austria (with a vote by BM Matthias Stadtler). In: reformation-cities.org/cities , accessed on October 20, 2017. On the importance of St. Pölten in the history of the Reformation, see also the section on the Early Modern Age .

- ↑ St. Pölten is applying for European Capital of Culture 2024. In: DiePresse.com . September 15, 2017. Retrieved November 8, 2019.

- ↑ St. Pölten 2024: Management and project manager of the Lower Austrian Capital of Culture 2024 GmbH appointed. In: st-poelten2024.eu, accessed on November 8, 2019.

- ↑ Statistics Austria: Population on January 1st, 2020 by locality (area status on January 1st, 2020) , ( CSV )

- ^ Climate data from Austria 1971–2000. ZAMG , St. Pölten station.

- ↑ Peter Scherrer: Archaeological overview and find catalogs. In: Thomas Karl u. a .: The art monuments of the city of St. Pölten and its incorporated localities. 1999, pp. XVII-LX, here: p. LIII.

- ↑ Thomas Karl: On the historical and urban development of St. Pölten from the early Middle Ages to the beginning of the city expansion around 1850. In: Thomas Karl u. a .: The art monuments of the city of St. Pölten and its incorporated localities. 1999, S. LXIII-LXXXV, here: S. LXIII.

- ↑ For example in Ammianus Marcellinus , Res gestae 16,2,12.

- ↑ Peter Scherrer: Archaeological overview and find catalogs. In: Thomas Karl u. a .: The art monuments of the city of St. Pölten and its incorporated localities. 1999, pp. XVII-LX, here: pp. LVII-LVIII.

- ↑ This is the conclusion Walter Pohl draws : The Avars, Ein Steppenvolk in Mitteleuropa 567–822 AD. 2nd edition. Beck, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-48969-9 , p. 310.

- ↑ Ronald Risy: Sant Ypoelten. Pen and city in the Middle Ages. In: Forum Archaeologiae . Volume 52/9, 2009.

- ↑ Thomas Karl: On the historical and urban development of St. Pölten from the early Middle Ages to the beginning of the city expansion around 1850. In: Thomas Karl u. a .: The art monuments of the city of St. Pölten and its incorporated localities. 1999, S. LXIII-LXXXV, here: S. LXIII-LXV.

- ↑ All earlier dates of the monastery building (such as the years 741 or 764) before Charles' Avar campaign are unlikely. Thomas Karl: On the historical and urban development of St. Pölten from the early Middle Ages to the beginning of the city expansion around 1850. In: Thomas Karl u. a .: The art monuments of the city of St. Pölten and its incorporated localities. 1999, S. LXIII-LXXXV, here: S. LXIII-LXIV.

- ^ Johann Kronbichler: Cathedral and diocese building. In: Thomas Karl u. a .: The art monuments of the city of St. Pölten and its incorporated localities. 1999, pp. 5–76, here: p. 54.

- ↑ Peter Scherrer: Archaeological overview and find catalogs. In: Thomas Karl u. a .: The art monuments of the city of St. Pölten and its incorporated localities. 1999, pp. XVII-LX, here: S. LX.

- ↑ Christoph Müller von Prankenheim, Albert von Maderna: Historia Canoniae Sand-Hippolytanae. Part 1, Trattner, Vienna 1779, p. 34 ff.

- ^ A b Thomas Karl: On the historical and urban development of St. Pölten from the early Middle Ages to the beginning of the city expansion around 1850. In: Thomas Karl u. a .: The art monuments of the city of St. Pölten and its incorporated localities. 1999, S. LXIII-LXXXV, here: S. LXIII-LXIV.

- ↑ Peter Scherrer assumes that Treisma was in the nearby towns of Pottenbrunn and Unterradlberg. For a discussion of Scherrer's assumption see Thomas Karl: On the historical and urban development of St. Pölten from the early Middle Ages to the beginning of the city's expansion around 1850. In: Thomas Karl u. a .: The art monuments of the city of St. Pölten and its incorporated localities. 1999, S. LXIII-LXXXV, here: S. LXIV-LXV.

- ↑ Max Heuwieser (ed.): The traditions of the Hochstift Passau, sources and discussions on Bavarian history. NF 6, Munich 1930, pp. 40-41.

- ↑ Theodor Sickel (Ed.): Diplomata 13: The documents Otto II and Otto III. (Ottonis II. Et Ottonis III. Diplomata). Hannover 1893, pp. 151–152 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version ) (Latin.).

- ↑ Entry on the city in the Austria Forum (in the AEIOU Austria Lexicon )

- ↑ 500 years of the Reformation in St. Pölten 1517 to 2017 (exhibition in the City Museum from May 12, 2017 to September 6, 2017). In: stadtmuseum-stpoelten.at, accessed on March 23, 2018.

- ↑ (red): 500 years of the Reformation in St. Pölten. In: mein district.at. November 24, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ↑ In 1679 the name Oppidum Sampoltanum is also mentioned in the Topographia Provinciarum Austriacarum ( Matthäus Merian (publisher and illustrator), Martin Zeiller (text author): Topographia Provinciarum Austriacarum. Merian, Frankfurt am Main 1679, p. 17 ).

- ↑ a b Elisabeth Linhart: St. Pölten in the years 1955–1970. In: Siegfried Nasko, Willibald Rosner (Hrsg.): St. Pölten in the 20th century. History of a city. 2010, pp. 152–196, here: p. 153.

- ↑ This section for March 1938 follows: Wolfgang Pfleger: The fateful March days 1938 in St. Pölten. In: St. Pöltner Regenbogen 98. Eggner, St. Pölten 1998, pp. 47–76, and Karl Gutkas: To the March days 1938 in St. Pölten. In: Bulletin of the cultural office of the city of St. Pölten. 3, 12, St. Pölten 1978.

- ^ The section on National Socialism follows: Markus Schmitzberger: St. Pölten in the Nazi era 1938–1945. In: Siegfried Nasko, Willibald Rosner (Hrsg.): St. Pölten in the 20th century. History of a city. 2010, pp. 96-121.

- ↑ This section follows: Franz Forstner: The incorporations of 1939. In: St. Pöltner Regenbogen 2000. St. Pölten 2000.

- ^ Ratzersdorf, Stattersdorf, Radlberg, Brunn, Harland, Altmannsdorf, Windpassing, Schnabling, Pyhra, Wörth, Hart, Wolfenberg, Völtendorf, St. Georgen am Steinfelde, Gattmannsdorf, Gröbern, parts of Pummersdorf.

- ↑ Thomas Pulle: Urban Development from the Middle of the 19th Century to the Present. In: The art monuments of the city of St. Pölten and its incorporated localities. Berger & Sons, Horn 1999, CV.

- ↑ Manfred Wieninger: St. Pöltner tell street names. Studienverlag, Innsbruck 2002.

- ↑ a b Martha Keil, Christoph Lind: The Jewish community of St. Pölten. In: injoest.ac.at, accessed on November 25, 2019.

- ↑ Martha Keil, Christoph Lind: Search for traces: The Jewish St. Pölten. In: david.juden.at, accessed on November 25, 2019.

- ↑ Christoph Lind: "... there were such nice people there". The destroyed Jewish community of St. Pölten (= Jewish communities. Volume 1; part of: Anne Frank Shoah Library ). With the collaboration of Matthias Lackenberger. NP-Buchverlag, St. Pölten 1998, ISBN 3-85326-101-9 , p. 137.

- ↑ Christoph Lind: The destroyed Jewish community in St. Pölten. In: Institute of the Jews in Austria (ed.): To restore history? St. Pölten 2000, OCLC 470702553 , p. 22, and Siegfried Nasko: Wera Heilpern, St. Pölten's Anne Frank, survived. In: St. Pölten specifically. No. 12, 1988, OCLC 85280435 , pp. 18-19.

- ↑ A list of the individual companies can be found in: Markus Schmitzberger: St. Pölten in the Nazi era 1938–1945. In: Siegfried Nasko, Willibald Rosner (Hrsg.): St. Pölten in the 20th century. History of a city. 2010, pp. 106-109.

- ^ Markus Schmitzberger: St. Pölten in the Nazi era 1938–1945. In: Siegfried Nasko, Willibald Rosner (Hrsg.): St. Pölten in the 20th century. History of a city. 2010, pp. 96–121, here: pp. 110–112 and 118.

- ^ Siegfried Nasko: Resistance in St. Pölten. In: St. Pöltner Regenbogen 2000. St. Pölten 2000, p. 63.

- ↑ Karin Reiter: The organized resistance against National Socialism in St. Pölten and the surrounding area 1938–1945. St. Pölten 1996, p. 17 f.

- ^ Markus Schmitzberger: St. Pölten in the Nazi era 1938–1945. In: Siegfried Nasko, Willibald Rosner (Hrsg.): St. Pölten in the 20th century. History of a city. 2010, pp. 96–121, here: p. 113; P. 124.

- ^ Markus Schmitzberger: St. Pölten in the Nazi era 1938–1945. In: Siegfried Nasko, Willibald Rosner (Hrsg.): St. Pölten in the 20th century. History of a city. 2010, pp. 114–117.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Franz Forstner: 1945. End and beginning. In: Siegfried Nasko, Willibald Rosner (Hrsg.): St. Pölten in the 20th century. History of a city. 2010, pp. 122–151.

- ↑ The rural districts: Ratzersdorf, Ober- and Unter Zwischenbrunn, Windpassing, Schnabling, Wörth, Wolfenberg, Hart, Gröben, Schwadorf, Gattmannsdorf as well as parts of Altmannsdorf, Brunn and Pummersdorf. Remaining with the community: Ober- and Unterradlberg, Stattersdorf, Harland and Völtendorf. Elisabeth Linhart: St. Pölten in the years 1955–1970. In: Siegfried Nasko, Willibald Rosner (Hrsg.): St. Pölten in the 20th century. History of a city. 2010, pp. 152–196, here: p. 153.

- ^ Elisabeth Linhart: St. Pölten in the years 1955–1970. In: Siegfried Nasko, Willibald Rosner (Hrsg.): St. Pölten in the 20th century. History of a city. 2010, pp. 152–196, here: pp. 154 f.

- ^ Elisabeth Linhart: St. Pölten in the years 1955–1970. In: Siegfried Nasko, Willibald Rosner (Hrsg.): St. Pölten in the 20th century. History of a city. 2010, pp. 152–196, here: pp. 153 f.

- ^ SPÖ changes the vice before the election in St. Pölten. February 11, 2020, accessed June 13, 2020 .

- ↑ 2nd Vice Mayor Ing.Matthias Adl, ÖVP. In: st-poelten.at. September 23, 2019, accessed November 25, 2019 .

- ↑ State history of Lower Austria. 2nd edition 1994, p. 168.

-

↑ town twinning. In: st-poelten.gv.at, accessed on November 25, 2019. -

Wuhan. In: partnerstaedte-stpoelten.at, accessed on November 25, 2019. - ^ Citizens' service, forms from A – Z. In: st-poelten.at. Retrieved November 25, 2019 .

- ↑ For the years 1869–2001: Statistics Austria: A look at the community of St. Pölten (PDF; 36 kB); for the years 2002–2010: Statistics Austria: Population and components of population development - St. Pölten (PDF; 17 kB), population on December 31st.

- ↑ 2011 accounts. (PDF; 3.6 MB) (No longer available online.) Stadt St. Pölten, p. 4 , archived from the original on April 2, 2015 ; accessed on February 27, 2018 .

- ↑ Statistics Austria: Workplace census from May 15, 2001 - Workplaces and employees compared to 1991 (PDF; 6 kB).

- ↑ a b Statistics Austria: Workplace census from May 15, 2001 (PDF; 15 kB).

- ↑ Statistics Austria: Sample census 2006: Workplaces (PDF; 7 kB).

- ↑ Statistics Austria: Workplace Census 2001: Main Results Lower Austria. November 2004, ISBN 3-902452-58-7 , p. 374, table A5 ( statistik.at [with link to PDF; 8.4 MB]).

- ↑ Statistics Austria: Employees by commuting destination. (PDF; 51 kB) In: statistik.at, accessed on May 23, 2020.

- ↑ District heating transport line from Dürnrohr to St. Pölten. In: evn.at, accessed on December 28, 2016.

- ↑ St. Pölten: Voith closes the paper machine plant. In: derStandard.at . February 2, 2015, accessed February 2, 2015.

- ↑ Sunpor is increasing production ( memento of November 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) ( access restricted).

- ^ Location data Unterradlsberg ( Memento from April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ). (PDF; 5.5 MB) In: egger.com, September 9, 2014, accessed on December 28, 2016.

- ↑ Paper manufacture with tradition. In: salzer.at, accessed on December 28, 2016.

- ↑ Geberit in Austria. In: geberit.at, accessed on December 28, 2016.

- ↑ Good apprenticeship training at Geberit in St. Pölten - Minister of Education Claudia Schmied visits Geberit Austria in Pottenbrunn. In: magzin.at, April 13, 2012, accessed on December 28, 2016.

- ↑ Company information on kika.com ( memento from January 5, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), company chronicle on kika.com (detailed up to October 2013) ( memento from February 11, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) and chronicle (up to 2018). In: kika.at, accessed on December 1, 2018.

- ↑ Leiner. Success with history and future. (No longer available online.) In: leiner.at. July 12, 2009, archived from the original on July 12, 2009 ; accessed on May 1, 2018 .

- ↑ Mario Kern: Nadlinger takes over bauMax in the north. In: noen.at. Niederösterreichische Nachrichten , September 27, 2015, accessed on October 20, 2017 .

- ↑ Nadlinger also in the north of St. Pölten from spring. In: nadlinger.at. Baumarkt Nadlinger Handelsges.mbH, September 29, 2015, accessed on October 20, 2017 .

- ↑ NÖ Pressehaus Druck- und VerlagsgmbH: Die neue NÖN, Pielachtal edition . Issue No. 32 from August 7, 2018, page 19

- ↑ Editor: Austria's largest media company. In: derstandard.at, May 30, 2007, accessed on March 23, 2018.

- ↑ www.salesianer.at .

- ↑ team. In: schubert-franzke.com , accessed on March 23, 2018.

- ↑ Vienna, Innsbruck and Bregenz are Austria's front runners in environmentally friendly mobility. VCÖ, February 18, 2016, accessed on July 19, 2020 .

- ↑ In Vienna, Innsbruck, Graz and Linz, car motorization is lower than in 2010 - mobility with a future. VCÖ, May 29, 2017, accessed on July 19, 2020 .

- ↑ Cycling in St. Pölten. Retrieved on July 19, 2020 (German).

- ^ Caritas St. Pölten, Care and Maintenance, St. Elisabeth House. (PDF; 217 kB) In: caritas-stpoelten.at. Caritas of the Diocese of St. Pölten, accessed on August 3, 2019 (status: summer 2014).

- ↑ List of fire brigades in the St. Pölten-Stadt section on the St. Pölten district fire department website , accessed on April 29, 2013.

- ^ Education on the homepage of the city of St. Pölten, accessed on November 25, 2019.

- ^ Annual report 2002 of the St. Pölten city library. Austria Press Agency . January 17, 2003, accessed August 27, 2013.

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Alscher: History of the Lower Austrian State Library. 2013, p. 103.

- ↑ inventory. (No longer available online.) In: pbn.lsr-noe.gv.at. Federal educational library at the regional school board for Lower Austria, archived from the original on December 16, 2013 ; accessed on May 1, 2018 .

- ↑ History of the library on the homepage of the library of the Philosophical-Theological University of St. Pölten, accessed on December 6, 2018.

- ^ Library on the homepage of the St. Pölten University of Applied Sciences, accessed on August 27, 2013.

- ^ Dehio manual. The art monuments of Austria. Lower Austria south of the Danube . Berger, Horn / Vienna 2003.

- ↑ Helmut Reindl: Where Austria's most popular market can be found. In: Municipal . March 21, 2019, accessed April 17, 2020.