soul

The term soul has a variety of meanings depending on the different mythical, religious, philosophical or psychological traditions and teachings in which it appears. In today's linguistic usage, the totality of all emotions and mental processes in humans is meant. In this sense, “soul” is largely synonymous with “ psyche ”, the Greek word for soul. “Soul” can also designate a principle which is assumed to underlie these impulses and processes, to order them and also to bring about or influence physical processes.

In addition, there are religious and philosophical concepts in which “soul” refers to an immaterial principle that is understood as the carrier of the life of an individual and of his or her permanent identity through time . Often associated with this is the assumption that the soul is independent of the body and thus also of physical death with regard to its existence and is therefore immortal . Death is then interpreted as the process of separating soul and body. In some traditions it is taught that the soul already exists before conception, that it inhabits and guides the body only temporarily and that it is used as a tool or that it is imprisoned in it as in a prison. In many such teachings, the immortal soul alone constitutes the person; the ephemeral body is viewed as insignificant or as a burden and obstacle to the soul. Numerous myths and religious dogmas make statements about the fate that awaits the soul after the death of the body. In a large number of teachings it is assumed that a transmigration of souls ( reincarnation ) takes place, that is, that the soul has a home in different bodies one after the other.

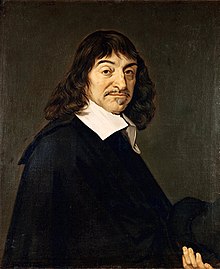

In the early modern period , from the 17th century onwards, the traditional concept of the soul, derived from ancient philosophy, as the life principle of all living beings that controls physical functions, was increasingly rejected, since it was not needed to explain affects and body processes. The model of René Descartes was influential , who only ascribed a soul to humans and limited its function to thinking. Descartes' teaching was followed by the debate about the “ mind -body problem ”, which continues and is the subject of the philosophy of mind today. This involves the question of the relationship between mental and physical states.

A wide range of highly divergent approaches is discussed in modern philosophy. It ranges from positions that assume the existence of an independent, body-independent soul substance to eliminative materialism , according to which all statements about the mental are inappropriate because nothing corresponds to them in reality; rather, all seemingly “mental” states and processes can be completely reduced to the biological. Between these radical positions there are different models that do not deny the mental reality, but only conditionally allow the concept of the soul in a more or less weak sense.

Etymology and history of meaning in German

The German word "Seele" comes from Middle High German sële and Old High German së (u) la , Gothic saiwala from a primitive Germanic form * saiwalō or * saiwlō . According to one hypothesis, this is derived from the also ancient Germanic * saiwaz (lake) as "the lake that comes from the lake" ; the connection is said to be that, according to an old Germanic belief, the souls of people live in certain lakes before birth and after death. However, it is unclear how widespread this belief was; therefore the connection is not generally accepted in research, especially since a connection between the realm of the dead and * saiwaz (or forms derived from it) is not documented in Germanic sources. A connection with Sami saivo is assumed, an ancient Norse loan word that denotes a realm of the dead.

Already in Old High German and Middle High German, formulaic expressions such as “with (or on) body and soul” were frequent, which in the sense of “completely, completely” explicitly refer to the whole person. The expression “ beautiful soul ”, popular since the late Middle Ages, has ancient (nobilitas cordis) , old French (gentil cuer) and spiritual (edeliu sêle) roots and appears programmatically in the variant of the noble heart with Gottfried von Strasbourg († around 1215). In the 14th century, “beautiful soul” became common in spiritual literature. In a religious sense, the term is still used in Pietism , for example by Susanna Katharina von Klettenberg , a friend of Goethe's mother. Since 17./18. Century often means “soul” the whole person (“he is a good soul”; “no soul” for “nobody”).

The current of sensitivity in the Age of Enlightenment also used “beautiful soul” in a further, no longer just religious sense to mark a sensitive and virtuous mind or person. Friedrich Schiller uses the “beautiful soul” to describe the harmony of sensuality and morality. In this sense, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel interprets Jesus in his theological writings for young people. Friedrich Nietzsche , on the other hand, formulates sarcastically : “To demand that everything should be 'good people', herd animals, blue-eyed, benevolent, 'beautiful soul' - or, as Mr. Herbert Spencer wishes, be altruistic , would mean depriving existence of its great character castrate humanity and bring it down to a poor Chinese. - And this has been tried! ... This was called morality. ”In the opinion of Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer , bourgeois society granted women“ acceptance into the world of domination, but as broken ”, and then praised her as a beautiful soul; behind this facade, however, the woman's desperation over her subjugation was hidden.

In the 20th century, the foreign word “psyche” became common due to the use of language in psychology. It stands for a more sober, more scientifically oriented view of the human inner life without the emotional overtones of "soul". The difference between psyche and soul becomes clear in Goethe, for example, who has his figure of Iphigenia on Tauris exclaim: "And on the shore I stand for long days, searching the land of the Greeks with my soul". According to the linguistic feeling of today's readers, "looking for the land of the Greeks with their psyche " would be inappropriate here.

Traditional ideas and teachings

Ethnic religions

In many indigenous cultures , whose religious traditions are examined by general and comparative religious studies, there is an abundance of ideas and terms that roughly relate to what Europeans traditionally understand by soul (in the metaphysical- religious sense), or at least to something in a certain way Respect to it comparable. From a religious-scientific point of view, “soul” includes everything that “ reveals itself to religious people (in themselves and in others) as the power of physical and hyperphysical (paraphysical, parapsychic, psycho-spiritual and post-mortem ) life”. In indigenous traditions it is usually assumed that the variety of mental and physical functions corresponds to a variety of causers. This results in the assumption of a multitude of independent psychic powers and forces or even independent “souls” that are active in an individual and bring about the manifold expressions of life. There is a separate term for each of these instances, but the assignment of the individual functions to the psychic powers is often vague. In some cases it is unclear to what extent individual or rather supra-personal aspects are in the foreground in the ideas of these powers. Often there is no need to distinguish between subjective and objective reality. Likewise, no fundamental distinction is made between material and spiritual ; nothing is exclusively material and nothing is purely spiritual. The soul is usually thought to be more or less material or subtle and only comes into focus in connection with its physical carriers or its perceptible manifestations .

Despite the uncertainty, a classification can be made; Criteria for this are on the one hand the function of the soul and its spatial relationship to its wearer, and on the other hand its shape .

The consideration of the soul from the point of view of function and relationship to the wearer results in the following classification:

- The vital soul (body soul ) regulates the body functions. As part of the organism, it can be inextricably linked to a specific organ or part of the body. The head, throat, heart, bones, hair and blood appear as the seat or physical carrier of such a soul in different cultures. The existence of this soul ends with that of the body.

- The ego-soul regulates the spiritual life in the normal state (waking state) and enables self-confidence . It is also bound to the body or a certain organ and is mortal.

- The free soul (excursion soul) can leave the body, which happens in sleep or in ecstasy. At death she gives up the body and becomes the soul of the dead; through its immortality it enables the individual to continue to exist. It can move to an afterlife (realm of the dead) or also remain in this world or return there or, according to some traditions, as a reincarnation soul inhabit different bodies one after the other.

- The outer soul stays outside of the body and connects people with their natural environment or with a spiritual or otherworldly area. If it is considered destructible, its annihilation means death for humans.

The consideration from the point of view of the shape leads to the differentiation of the following manifestations of the soul:

- The soul appears in human form. This does not have to correspond in every case to the physical form of the individual concerned; so the excursion soul of a man often appears as a woman.

- The soul assumes an animal form, especially often that of a bird ("soul bird").

- The soul shows itself in elemental or subtle form. Such an elemental soul is imagined as air, wind, breath, fire, light, water or smoke.

- The soul becomes noticeable as an optical or acoustic phenomenon, for example as a shadow, mirror image or sound (especially as a name).

It should be noted that, depending on the religious tradition, one or more of the functions mentioned can be assigned to one of the soul terms.

On soul performances in the Neolithic let cemeteries with Early Neolithic cremations close that indicate an intention clearly to facilitate the as subtle-conceived soul the way to the afterlife. The deceased's possessions and meat food as food for the journey were also put on the stake.

India

The religious and philosophical concepts of Indian origin are based partly on the Vedic religion , from which the various currents of Hinduism have developed. However, some teachings are in sharp contrast to the authority of Vedic literature: Buddhism , Sikhism, and Jainism . A common feature of all Indian traditions is that they make no distinction between human souls and the souls of other life forms (animals, plants, even microbes).

The ancient Indian teachings, with the exception of the materialistic (nāstika) and Buddhism, assume that the human body is animated by a vital soul ( jīva , literally “life”, “living being”), which is also the carrier of individual self-awareness (I-soul ) is. Each jīva can also inhabit any other living being body. In the cycle of rebirth ( samsara , transmigration of souls) it connects one after the other with numerous human, animal and vegetable bodies. The soul or the self therefore always has priority over the body and survives its death. In Buddhism, this applies to the totality of the mental factors that shape an individual rather than the soul. At death the soul separates from the body. The ego-soul is therefore at the same time a free soul; as such it is also called ātman or purusha .

The traditional systems, which assume the existence of a soul, a self or the body of enduring spiritual components of the living being, consider the connection of the soul with material bodies or the formation of a mind-body complex as a fault and a misfortune, its final elimination and future avoidance is sought. The way to do this is to remove ignorance. This is called release ( moksha ) from the cycle and is the ultimate goal of philosophical or religious endeavors.

An essential difference to the soul conceptions of Platonic or Christian origin that dominate in the West is that in a large part of Indian religious-philosophical teachings the individual soul is not regarded as eternal. It is often assumed that one day it will dissolve into a superordinate, impersonal metaphysical reality ( Brahman ) with which it is of the same nature. According to this view, she once separated herself from the comprehensive existence of Brahman or under the illusion that such separation existed; if she reverses this process, her individual existence or the self-delusion that such an existence actually exists ends. In order to distinguish it from the common Western concept of soul, the translation and commentary of texts from such traditions is often deliberately not using the term "soul".

Hindu directions

In Hinduism there are two main directions, the teachings of which are basically incompatible despite attempts at harmonization: Vedanta and Samkhya . For its part, the philosophy of Vedanta is divided into Advaita (“non-duality”, monism ), Dvaita (“duality”, dualism ) and Vishishtadvaita , a moderately monistic teaching that assumes a real multiplicity within the unity.

Advaita adherents are radical monists who only accept a single, unified metaphysical reality. They consider all plurality or duality to be a pseudo-reality that dissolves when it is seen through. Accordingly, the individual souls, as well as the bodies animated by them, do not exist ontologically as independent entities , but are illusory components of an actually worthless and meaningless pseudo world of perishable individual things.

Opposite positions to the Indian radical monism are the dualism of the Samkhya philosophy and the classical yoga of Patañjali , according to which the primordial matter and the primordial soul are two eternal primordial principles, the moderate monism (Vishishtadvaita after Ramanuja ), which many practitioners of Bhakti Yoga represent, and the view of the 13th century Brahmin Madhva , who regarded God, the individual souls and matter as three eternal entities. In these systems, which reject radical monism, a real individual immortality of the soul (of the self) is affirmed; The goal is the final exit from the cycle of the transmigration of souls and entry into a world beyond, in which the soul remains permanently.

Buddhism

The Buddhism represents mainly the Anatta -Teaching. Anatta , a word in the Pali language , means “not-atman”, that is, “not-self” or “not-soul”. Buddhists deny the existence of a soul or self in terms of a unified and constant reality that survives death. From a Buddhist point of view, that which survives death and keeps the cycle of rebirth going is nothing but a transitory bundle of mental factors, behind which there is no person core as an independent substance. Sooner or later, this complex dissolves into its constituent parts, gradually transforming itself, with parts being eliminated and others being added. The metaphysical term ātman (soul) is therefore empty, since it has no constant content.

Sikhism

In Sikhism , the world and the living beings (souls) in it are viewed as real, but not as eternal. They emerged from God through emanation and would return to him.

Jainism

In Jainism , the individual soul (jīva) is seen as immortal. It can purify itself through asceticism , free itself from its connection with the material forms of existence and transfer to a world beyond, in which it remains permanently and without any contact with the material world and its inhabitants. She has to accomplish her redemption by her own strength, since the Jainas as atheists do not consider divine assistance possible.

Ajivikas

The Ajivikas have disappeared as a ideological community; They can be proven up to the 14th century. It was a strictly deterministic trend. They assumed an immortal but material soul consisting of a special kind of atoms without free will , whose fate is inevitably carried out according to given necessity.

Ancient Indian materialism

The ancient Indian atheistic materialism has perished as a philosophical school. His representatives, who were called nastikas (negators, negativists), included in particular the followers of the Lokayata doctrine, which came from Charvaka and which was introduced as early as the first millennium BC. Was common. They accepted only four sensible elements as real and viewed all mental phenomena as the result of certain temporary combinations of the elements that end with physical death. On the basis of this conviction, they denied the existence of gods, a moral world order and a soul different from the body.

China

Like many prehistoric and indigenous peoples, the Chinese in prehistoric times had different expressions for the souls in an individual. A body soul ( p'o or p'êh ) and a breath soul (hun) were accepted as two separate entities in man. The body soul is responsible for physical functions (especially the movement of the body), the breath soul for consciousness and intellect. The breath soul is a free soul and excursion soul, which can leave the body during its lifetime and finally separates from it when it dies. The body soul also persists after death, but it remains connected to the body and normally accompanies it to the grave, where the grave goods are intended to ensure its well-being. In addition, the 8th century BC existed. Chr. Attested idea that the P'o-soul of a deceased can get into the underworld, to the yellow springs (Huángquán) , where it goes badly. In the traditional Chinese system of universal classification , the P'o soul is assigned to the dark, feminine Yin principle and the earth. It arises at the same time as the embryo. The Hun soul is assigned to the male, bright Yang principle and heaven. It arises when a person comes into the light at birth. With the food the person takes in subtle matter (ching) , which is needed by both souls for strengthening. Thus, both souls are not thought of as immaterial. After a natural death of the body, the Hun soul can go to heaven or to another realm. In the event of a violent death, however, it is to be expected that both souls will remain in the social environment of the deceased and drive their mischief there as spirits of greed and revenge. A spiritual entity that is inherent in the human being and survives his body, but has arisen (not individually pre-existing), was also referred to as shen .

The very early, at the time of the Shang state in the 2nd millennium BC. BC, strongly developed ancestor cult - a constant in Chinese cultural history - and the rich prehistoric burial equipment are not only to be interpreted as an expression of piety towards the ancestors, but show the power of the idea that the souls of the dead have the same needs as the living and that they intervene in the life of the bereaved in a supportive or disruptive manner.

Mo Ti , who lived in the 5th century BC. BC founded the Mohism named after him, taught the continued existence after death. The followers of the since the 2nd century BC In contrast, Confucianism , which was established as a state doctrine in China , regarded speculations about it as useless and left the topic to traditional Chinese folk religion .

A philosophical controversy about the soul and the question of whether a spiritual or mental entity survives the body or even continues to exist forever, apparently only started late, when it was at the time of the Han dynasty (206 BC - 220 AD) . BC) Buddhism began to spread. Skeptics and materialists took part in the debate who opposed the idea of an independently existing soul and traced all mental functions back to physical ones. In this sense, the philosophers Wang Chong (1st century AD) and Fan Zhen (5th / 6th century AD ) argued . Fan Zhen wrote a treatise on the annihilation of the soul (Shenmie lun) that caused a sensation at the court of Emperor Wu by Liang. The polemics of the skeptics were directed against Buddhism, since the Buddhists were regarded as adherents of the immortality idea. Buddhism actually strongly rejects the concept of an immortal soul, but in China it has often been modified by popular beliefs that resulted in a permanent soul progressing through the cycle of rebirth.

Japan

In Japan, the traditional ideas of the soul are closely related to the ancestral cult that has been widespread since prehistoric times and was an important part of indigenous folk religion, an early form of Shintoism . They are also influenced by the Japanese forms of Mahayana Buddhism introduced in the 6th century . Different variants of the old Shinto folk belief said that the souls of the deceased either live in the underworld ( yomo-tsu-kuni or soko-tsu-kuni ) or in a heavenly realm ( takama-no-hara ) , or in a "permanent one." Land “ (toko-yo) referred to the realm of the dead on the other side of the ocean. But it was also assumed that they are not inaccessible there, but that they seek out this world and dwell with people. From the 9th century, after Japanese Buddhism gained considerable influence over religious mores , popularly popular celebrations were held to appease the anger of souls from the violent deaths. Soul shrines were built to commemorate prominent deceased people who had been wronged during their lifetime and whose souls were to be appeased.

According to another view, widespread up to the modern age, the dead souls live on certain high mountains. Hundreds of thousands of pilgrims went to the famous place of worship on Mount Iya every year in the 20th century. A highlight of the cult of the soul is the Buddhist Obon festival, which has been celebrated annually in the summer since the 7th century , for which families gather; this is not intended to provide the living with the blessing of the dead souls, but rather the ritual acts are intended to serve the welfare of the dead souls, who return to their living relatives on this occasion.

The name for the soul is tama or mitama (basic meaning: precious, wonderful, mysterious). The tama was viewed as inconsistent; a mild and happy part of the soul cares about the well-being of the person, another part is wild and passionate, exposes people to risk and can also do wrongdoing. The conviction was and is widespread that the souls of the living leave the body as excursion souls.

Old Egypt

In ancient Egypt , three terms were used to denote three aspects of the soul: Ka , Ba and Ach . Characteristic of the ancient Egyptian way of thinking is a very close connection of the soul to the physical and therefore even beyond death to the corpse and its grave. The buried corpse was still considered to be capable of being animated and thus in principle capable of acting. Therefore, the preservation of the body through mummification was of central importance for the Egyptian belief in the dead. But there were also various ideas about an existence in the hereafter ; apparently hardly any attempt was made to combine the different concepts into a coherent whole.

The term Ka , which was dominant in the era of the Old Kingdom , denoted the source of life force. According to the Egyptian understanding of the soul, the presence of the Ka made the difference between a living person and a corpse. Furthermore, the Ka could function as a doppelganger or guardian spirit of the person concerned. It was "constant" and a guarantee of continuity, because it was passed on from father to son and thus stood for the uninterrupted continuation of the life force in the line of ancestors. Therefore, he was very prominent at birth. When he died, he left the body but stayed close to it. His abode was a statue erected especially for him in the grave, where he was indispensable for the survival of the person. In the Old Kingdom, food and drink were made available for the ka - that is, for the corpse it was supposed to animate - at a sacrificial site above the grave. The idea was so material that logically there was even a toilet in some graves. However, this care for the dead was only considered for members of the upper class. Several kas have been ascribed to kings and gods , and the term ka occurs in the plural for a person in prayers for the dead in private graves of the Old Kingdom .

In the Middle Kingdom , the concept of Ba gained increasing importance. When Ba is called a personal life force that is at that time, according to faith carrier of individual existence and survives death. In the Old Kingdom, Ba was seen as a manifestation of special power and apparently only ascribed to the king, but later the concept was expanded to include all people in a modified form. The term Ba was understood to mean a very flexible aspect of the soul, which according to popular belief is already present in living people, but hardly plays a role; it only emerges at death, because physical death means a kind of birth for him. Most of the time Ba was depicted as a bird, often with a human head. This shows that it belongs to the type of "soul bird" that is widespread among indigenous peoples. According to Egyptian beliefs, the Ba birds were actually celestial beings and lived in a northern region ( Qebehu ) , but Ba , like Ka , retained a permanent bond with the corpse, that is, with the mummy. In order to induce the ba to visit the tomb - which was apparently regarded as a kind of resuscitation of the corpse and was very much desired - drinking water was provided there to attract him.

The Ach (spirit of light, derived from a word for "shine of light") was the transfiguration soul of a deceased, which only arose after his death. In contrast to the Ka , it was not tied to a specific location. Ach was a god-like form of existence that was achieved after death through appropriate efforts, in that the dead appropriated the Ach power and thereby became an Ach . Magical-ritual measures served this purpose. This included rites that were performed on the grave, inscriptions that were placed there or on the coffin, and texts that the deceased had to recite. Of gods such as Re and Osiris to help hoped when Oh -Werdung. If the transfiguration rites were carried out correctly at the grave, the deceased achieved the status of an “effective”, “equipped (fully equipped)” and “venerable” Oh ; as such he could influence the world of the living. In contrast to Ka and Ba , the “effective” oh could show himself as a ghost and intervene in people's lives in a beneficial or damaging manner. Like Ka and Ba , Ach showed a strong connection to the grave and an interest in its condition. There, the Egyptians deposited her at the Ah -looking of those buried messages.

Some aspects of oh- faith have changed; In the Old Kingdom, for example, a ceremonial feeding of the Ach was carried out, but later, in contrast to the Ka and Ba, he no longer required any material provision in performing the service of the dead. In the older form of this belief, moral behavior was immaterial; There were no ethical prerequisites for the Ach status ; an Ach , like a living person, could be good or malicious. In the New Kingdom is, however, a connection between moral merit and began Oh -Will make.

The ideas of the realm of the dead were strongly shaped by the numerous dangers that threatened the deceased there, partly due to the inhospitable nature of the area, partly due to the pursuit of demons . For example, demons tried to catch the bird-shaped ba with bird nets. Detainees were at risk of torture and maiming. On the other hand, divine assistance and, above all, knowledge of the fixed spells required to banish the dangers , which are handed down in coffin texts, helped . The existence on the other side was a continuation of the life on the other; so there was also farm work there. The dead resided "in the west" and were the "people of the west" (Imentiu) , the living lived in the east (on the Nile).

The dead were put before the judgment of the dead , where their hearts were weighed against the truth ( Maat ) with a scale , that is, their freedom from wrongdoing was tested ( psychostasis ). In the event of conviction, they were eaten by an ammit, i.e. destroyed. This moral concept competed and mingled with the ethically indifferent one, which made the post-death fate dependent on the correct practice of ritual magic .

Thus, according to ancient Egyptian ideas, souls were neither immaterial nor in principle indestructible. They did not exist before the formation of the body, reincarnation was not considered. Those who escaped the dangers beyond or were acquitted by the judgment of the dead were promised a happy life in a pleasant world, but such promises have met with serious doubts in some circles since the time of the Middle Kingdom. Skeptics questioned the effectiveness of the elaborate precautions for a happy, or at least satisfactory, afterlife. They pointed to the uncertainty of fate after death or the bleak prospects for the deceased. With the degradation of the hereafter, the request was often connected to strive for enjoyment of life in this world.

Mesopotamia

Neither the written sources nor the archeology offer concrete information about the ideas of the soul of the Sumerians and later the Akkadians , although the Sumerian religion , to which the Akkadian religion is closely related, can be easily deduced from the sources. In the Sumerian and Akkadian languages , there are no expressions whose meanings coincide with that of “soul”. The Akkadian term napischtu (m) / napschartu (“throat”, “life”, “life force”, also “person”) can be seen as a name for a soul, analogous to the related Hebrew words nefesch and neschama , which are derived from the The concrete basic meaning of "breath" refers to the life that appears in the breath. With this (and with other terms of the same or similar meaning) only a vital soul (body soul) of humans and animals that arises and dies with the body is meant; there are no further conclusions. The corresponding word in Sumerian is zi , which is related to the verb zi-pa-ag 2 (“to breathe”, “to blow”); There is a phrase zi-pa-gá-né-esch , which refers to checking whether there is still life in a body or whether the breath of life has left it. In addition, in Sumerian there is the expression libic / lipic for “ inwardness ” (of the human being) and in Babylonian libbu for “heart”, comparable to our use of “heart” in psychological meaning. The Babylonians located the source of life force bestowed by a deity in blood as well as in breath. Apparently they placed no value on an anthropological analysis and a concrete description of the soul.

A realm of the dead kur-nu-gi-a ("land of no return") and a judgment of the dead are attested for the Sumerians. On the other hand, the idea was widespread among them that the dead were at their graves. Therefore, food and drink were offered to the deceased there. In Babylonia , too , the ancestor cult was very important for the welfare of the dead; the ancestors had to be provided with food every day. In an appendix to the Epic of Gilgamesh, Enkidu, who has descended into the realm of the dead, returns. H. his spirit of the dead (utukku) returns to the world of the living and describes the fate of the dead, which depends on the type of death, the number of their children and the care of the surviving relatives. The unburied and those whose graves were desecrated fared badly, because the spirit of the dead was evidently closely connected to the corpse.

The Mesopotamian peoples were convinced that malicious spirits of the dead (Sumerian gidim , Akkadian eṭimmu or eṭemmu ) as well as countless other demons cause harm to the living. The spirits of the dead were seen as visible and audible. In addition, there were also helpful guardian spirits, which may be comparable to the outer souls of humans known from various indigenous cultures . From the Atraḫasis epic (around 2000–1800 BC) it emerges that eṭemmu , the ghost-like aspect of man who survives death, was originally created together with the human body from the flesh of a slain god. The mortal vital soul, which existed until physical death, arose from the blood of God; it was considered to be the basis of the human mind (ṭēmu) .

Iranian highlands

The East Iranian Avestan language , which belongs to the old Iranian languages, has a number of expressions for the soul or for psychological functions that were already in use in the pre-Zoroastrian period and were largely used later in the documents of the Zoroastrian religion . In part, they relate to perceptual functions, for example uši (originally the ear, hence the hearing and, in a figurative sense, the comprehension, the understanding). Besides the vital soul ( ahu or uštāna than touch soul Vyana ) it gave the ruling Iran needs the active and independent of the body free soul ( urvan or as intellectual soul manah ) and dana , a spiritual entity with nourishing function. The fravašis played an important role ; these were protective ancestral spirits , but also outer souls of living pious people. In the latter sense, fravaši was apparently understood as a “higher self” that influenced people from outside during their lifetime. The immortal free soul living in the body united with its fravaši after its death . Expressions that originally referred to the body, such as tanu and the word kəhrp , which is etymologically related to “body” , were also used for the person as a whole, including the soul dimension, which indicates a non- dualistic thinking.

The Zoroastrians do not seem to have tried to elaborate a detailed anthropological theory of the soul and terminological clarity, at least no corresponding texts have been preserved. In Zoroastrianism, the idea is attested that the vital soul was created before the body and that this came about because the life force was "made physical" by the deity. This vital soul, the uštāna , was destroyed with the death of the body. A sharp distinction between “good” and “bad” people is characteristic of Zoroastrianism, not between a body that is bad in itself and a morally superior soul. Zoroastrianism does not seem to have known a total soul or world soul.

After death, the free soul urvan stayed near the corpse for three nights until it encountered its own daēnā . The daēnā appeared in female form, as a cow or as a garden, which indicates its nourishing function. As a woman, she was a beautiful girl or a hideous witch, depending on the deeds that man accomplished in his lifetime. After meeting her, the soul urvan set out on the path to the hereafter.

In addition to the notions of the afterlife of the soul, there was also a very old belief in a resurrection as the resurrection of dead bodies, which was considered possible if the bones of the deceased were kept intact and complete; evidently, from the point of view of life force, the bones were ascribed a spiritual quality. In its religious form within the framework of Zoroastrianism, this Iranian belief in the resurrection was directed towards an eschatological future in which a general world judgment was expected.

Pre-Christian antiquity

Oldest Greek ideas

The ancient Greek noun psychḗ (ψυχή) is related to the verb psychein (“to blow”, “to breathe”); it originally meant "breath", "breath" and therefore also "life". It is documented for the first time in the Homeric epics Iliad and Odyssey, which were initially passed down orally . It denotes something in humans and animals that normally does not seem to be active during the life of an individual, but whose presence is necessary for life.

The psychē in the sense of Homer's parlance leaves a person faint. In death it separates from the body and goes into the underworld as its shadowy image . In addition to the expression psychē , Homer also uses the term eidōlon (image, silhouette) for the disembodied soul . The soul of a deceased is so similar to the living person that Achilles tries in vain to embrace the soul of the dead Patroclus , which appears to him and addresses him. The poet lets the disembodied soul show feelings and reflect upon death. She whines, laments her fate and worries about the burial of the body.

The thymós - with this word Homer describes the source of the emotional impulses - is, like the psychē, necessary for life; he too leaves the body in death. The poet does not say that the thymós is going to the underworld, but at one point in the Iliad a living person wishes that this should happen. Homer describes the thymós as destructible. During human life it is increased or decreased by events. In contrast to the psychē , which appears like a cold breath, the thymós is hot.

Of the psyche is mentioned only in connection with life-threatening situations. So Achilles speaks of putting one's own psyche in danger in battle . Usually this term is limited to the meaning carrier of being alive , while the emotions - but also thoughts connected with them - take place in thymós . Another instance that is important for the mental functions is the nóos (in later Greek nous ). It is primarily responsible for activities of the intellect , but occasionally also appears as a carrier of feelings. There is no clear demarcation between the terms in the Homeric epics.

The thymós is located in the diaphragm, or more generally in the chest. The nóos is also located in the chest, but it is apparently intended to be immaterial. The psychē does not assign Homer a specific seat in the body. It is a prerequisite for life for animals as well as for humans. In the Odyssey, when a pig is slaughtered, its psycho escapes , but it is not known whether it will end up in the underworld. Hesiod and Pindar mention the serpent's psyche .

Change of meaning in the posthomeric period

In poetic and philosophical texts of the 6th and 5th centuries, a new, expanded term of psychē became commonplace , which included the meaning of thymós . For the poet Anakreon , the erotic sensations played out in the psychē , for Pindar it was the bearer of moral properties. In the tragedy, too, the soul appeared in a moral context; with Sophocles it could therefore be described as "bad". The old basic meaning - the invigorating principle in the body - was still common, to be animated (émpsychos) meant to be alive, but in addition the soul was now also responsible for the emotional life and thought about it.

The philosophical and religious movements of the Orphic and Pythagorean extended the archaic concept of the body leaving psyche . They expanded it into teachings in which the soul was considered immortal and more or less detailed statements were made about its fate after death. In these currents, as well as in Empedocles and in the poetry of Pindar - in marked contrast to Homer - optimistic assumptions about the post-death future of the soul were asserted. According to these concepts, under certain conditions, in particular by purifying itself from guilt, it can gain access to the world of gods and become divine or regain its own original divine nature.

Transmigration of souls

In some circles (Orphics, Pythagoreans, Empedocles) the doctrine of immortality was connected with the idea of the transmigration of souls and thus the assumption of a natural bond between the soul and a certain body was abandoned. The soul was given an independent existence even before the body was formed and thus a previously unknown autonomy. The earliest personality known by name who confessed to the transmigration of souls was Pherecydes of Syros , born around 583 , whose writing about the gods has not survived. His somewhat younger contemporary and alleged student Pythagoras spread this doctrine in the Greek-populated southern Italy; his prominence made her famous in wide circles. The early Pythagoreans believed that human souls also go into animal bodies; they assumed that there was no essential difference between human and animal souls.

Understanding of natural philosophy of the early pre-Socratics

The early thinkers, known as pre-Socratics , dealt with the soul from the point of view of natural philosophy . With them, the psychē appears as the principle of movement of the self and other moving. In this sense, Thales thought, besides living beings, also magnets and, because of their electrical attraction, amber, were animated, but not - as it was mistakenly assumed - other objects. Anaxagoras saw in the universal nous ( spirit ) the cause of movement and the ruler of all things including the animated; According to Aristotle, he did not make a clear distinction between the nous and the psychē , which he also called mover. He described the nous as the “finest” and “purest” of all things, so he didn't really think of it as immaterial. Some pre-Socratics also understood the soul as a principle of perception or knowledge.

The theoretical description of the soul as a life principle consisted predominantly in a reductive physicalism , which traced the psychē back to something material or similar to material (subtle matter). Empedocles is said to have taught that the psyche , which he associated with physical life in the traditional sense, consists of the four elements. Not she, but a being he called daimōn , was for him the immortal soul, to which he ascribed the transmigration of souls. The daimōn , whose liberation from the cycle of birth and death he sought, he expressly referred to as a god.

The soul is referred to as air in a fragment traditionally attributed to the philosopher Anaximenes , but which, according to current research, comes from Diogenes of Apollonia . Anaximander and Anaxagoras are also said to have thought they were airy. There was also a notion that some Pythagoreans, probably originally from medical circles , believed that the soul was a harmony of bodily functions. This view was incompatible with the idea of immortality.

In Heraclitus' doctrine of the soul, too , the details of which are not clear from the fragments obtained, the psyche has a material quality. It moves back and forth between two opposing states, one of which is wet or watery, the other dry. When it is dry and thus close to the fiery principle of reason , it is in its best possible condition and is wise . The extent of their understanding depends on that of their current drought. Drunkenness makes her wet and loses her ability to understand. If the watery principle asserts itself completely, the soul dies, but this does not appear to her as downfall, but rather it perceives it as pleasure. Thus, like the cosmos as a whole, it is subject to incessant processes of transformation. Heraclitus thought it was so profound that its limits could not be found.

Democrit's materialist model

Democritus , the last important pre-Socratics, explained in the context of his consistently materialistic interpretation of the world the soul as an agglomeration of spherical, smooth soul atoms, which differ from the other atoms by greater mobility, which they owe to their shape and smallness. The soul atoms of Democritus are not - as was often assumed in the older research literature - characterized by a fire-like quality. Rather, all atoms are of the same quality in terms of their material properties, they only differ in size, shape and speed. Phenomena such as warmth, cold and color arise only through the constant movement and interaction of the atoms. The soul atoms float in the air; through breathing they are removed from it and returned to it again. Death is the end of this metabolism, with it the soul atoms of the deceased disperse. Immortality of the soul is unthinkable in this system. Body and soul protect each other through their connection from the constantly threatening dissolution. The soul is an atomic structure whose components, the soul atoms, are constantly being exchanged; they continuously evaporate and are replaced by newly inhaled soul atoms. During life, the soul atoms are distributed throughout the body and set the body atoms in motion. All mental phenomena can also be explained mechanically by the movements of concentrated masses of soul atoms. Perception occurs when atoms detach themselves from the objects and flow out in the form of small pictures ( eidola ) in all directions; these images of the objects penetrate the eye and convey their shapes to the perceiver. The ethical behavior and well-being of the person are also caused by the atomic movements. Too violent atomic movements mean harmful emotional shocks; Calmness and a pragmatic attitude correspond to the relative stability of the atomic structures.

Socrates and Plato

In the version of the defense speech of his teacher Socrates (469-399) handed down by Plato , the idea comes to the fore that the care of the soul (epiméleia tēs psychēs) is a primary task. The well-being of the soul appears to be linked to man's ability to discern and access the truth:

"Best man, [...] you are not ashamed to care for money, as you get most of it, and for fame and honor, but for insight and truth and for your soul that it is in the best possible way not and you don't want to think about this? "

For Plato (428 / 7–348 / 7), who used to put his thoughts in Socrates' mouth in his works, the soul is immaterial and immortal, it exists independently of the body, i.e. even before its emergence. This results in a consistent anthropological dualism : soul and body are completely different according to their nature and according to their fate. Their temporary meeting and cooperation is therefore only temporarily significant, their separation worth striving for; the body is the “grave of the soul”. Socrates and Plato equate the soul with the person both ethically and cognitively. Since the soul alone has a future beyond death, all that matters is its advancement and well-being. Because of her likeness to God as an immortal being, she is entitled to rule over the perishable body. In several myths , Plato describes the life of the soul in the hereafter, the judgment of the soul and the transmigration of souls. In doing so, he links the fate of the soul with its ethical decisions.

With the following considerations, Plato wants to make his view plausible:

- For all of nature it is true that opposing things arise apart and merge into one another; therein consists of becoming and the cycle of nature which guarantees its continuation. Such opposites are also “life” and “being dead”, “dying” and “resurrection”. The development that leads to the end of life therefore corresponds to an opposite one that leads from death to resurrection. That means rebirth (transmigration of souls).

- The soul is able to grasp objects of knowledge ( ideas ) that cannot be perceived by the senses, such as “the just”, “the beautiful” or “ the good ”. She is driven by her own nature to focus her interest on it. This shows her kinship with what she strives for. The ideas exist beyond transience and independent of individual sensory objects. If the soul itself were perishable, it would have no access to the imperishable.

- Learning is an activity of the soul. It does not consist in the fact that the soul absorbs something new and foreign from the outside, but in the fact that it remembers - for example through an impulse from a teacher - of a knowledge that it actually already possessed before, but about which it up to could not consciously dispose of this point in time. This knowledge, the knowledge of ideas and all things, she brought with her from her prenatal existence. She acquired it in a "heavenly place"; Added to this are their experiences from their previous earthly lives and from the underworld. Through remembrance ( anamnesis ) she makes the buried knowledge available.

- The individual things move back and forth between the opposites, but the opposing poles themselves always remain the same. The soul is such a pole because it is the life within us. Hence she is deathless; Only something living can die, not life itself.

- In contrast to all objects, the movements of which are caused from outside and cease with the disappearance of the external cause, the soul moves itself and also moves other things. The property of being able to bring about movement as the first cause of movement is part of their nature and is a defining feature. This quality is therefore not only given to it in a certain period of time, but has no beginning and no end. As the first source of all movement, self-movement has no origin in the world of growth and decay, which does not have such a faculty and cannot produce it from within itself. Therefore the soul as the bearer of this ability is eternal.

- To every thing there are both beneficial and harmful factors; The latter includes, for example, an eye disease for the eye, and rust for iron. For the soul the evil that harms it is “injustice” - an act against one's own nature caused by ignorance. An unjust person shows that his wickedness does not destroy his soul as a disease destroys the body. The evil of the body can destroy the body, the evil of the soul cannot destroy the soul. So the soul is not destructible.

Plato explains the inner conflicts of people with the fact that the soul consists of essentially different parts, a rational (logistikón) based in the brain, an instinctive, desiring (epithymētikón) based in the abdomen and a courageous (thymoeidēs) based in the chest. The courageous part of the soul easily subordinates itself to reason, the desiring part tends to oppose it. For this, Plato uses the image of a horse-drawn carriage: as a charioteer, reason has to steer a pair of two horses of different kinds (will and desire) and at the same time to tame the bad horse (desire) so that each part of the soul fulfills its proper function. The natural order is given when reason curbs the sensual desires, which distract it from its essential tasks, and when in its search for truth it starts from the immaterial - the absolutely reliable world of ideas - and mistrusts the error-prone sensory perceptions. The functions are not strictly divided, rather each part of the soul has its own form of desire and has a cognitive ability. Therefore, the non-rational parts can also form their own opinions or at least ideas.

Due to the very different nature of its parts, the soul is inconsistent. Nevertheless, according to Plato's original concept, it forms a unity insofar as all parts of the soul participate in immortality and the existence of the soul on the other side. In his later work, however, Plato conceives the two lower parts of the soul as fleeting additions to the immortal rational soul. Through this independence of the rational soul, a three-part ( trichotomous ) image of man emerges ; man is composed of the rational soul, the non-rational soul area and the body; the person is the rational soul.

Since Plato regards every independent movement as evidence of soulfulness, he considers not only humans, animals and plants, but also the stars to be animated. He also attributes this characteristic to the cosmos as a whole; he describes him as a living being inspired by the world soul . According to his presentation, the rational world soul was created by the demiurge . He also mentions the individual souls at various points as something that has arisen. If one understands this statement literally in the temporal sense, it contradicts the principle of the beginninglessness of the immortal. The question of what exactly is meant by “become” (gégonen) therefore arose even for the ancient interpreters . Mostly they interpreted - probably rightly - the "creation" of the cosmos or the world soul in the sense of a metaphorical phrase that should indicate an ontological hierarchy and should not be understood in the literal sense of an emergence at a certain point in time. Accordingly, the soul is timeless, but ontologically it is something derived.

In Phaedrus' dialogue , Plato describes the soul as winged. After losing her wings, she descends to earth and takes on an earthly body. If a person philosophizes, his soul could grow new wings, which it would have in the hour of death.

Aristotle

Aristotle's doctrine of the soul is set out in his work on the soul ( Peri psychēs , Latin De anima ); He also expresses himself about it in his small writings on the philosophy of nature ("Parva naturalia"). The treatise On the Soul also provides a wealth of valuable information about the pre-Socratics' ideas of the soul. In his youth, Aristotle wrote the dialogue Eudemos or On the Soul , which is lost except for fragments.

Aristotle discusses and criticizes the views of earlier philosophers, especially those of Plato, and presents his own. He defines the soul as “the first entelechy ” (actuality, realization, perfection) “of a natural body that potentially has life”; he describes such a body as "organic". The statement that the body potentially has life implies that it is inherently only suitable for being animate; that the animation is actually realized, results from the soul. The soul cannot exist independently of the body. It is its form and therefore cannot be separated from it. With the first reality of the soul, Aristotle addresses its basic activity, which does not stop even during sleep. The basic activity holds the organism together and ensures that it does not disintegrate. It differs from the activities of individual aspects of the soul, which correspond to the various faculties of the soul, according to which Aristotle classifies life.

The basic vegetative soul faculties of nutrition, growth and reproduction apply to all life, perception, locomotion and the ability to strive only to animals and humans. Thinking is peculiar to man only. The peculiarity of the human being, his authority responsible for the thinking activity, is the mind ( nous ) . The nous is indeed created as a possibility, as a “possible intellect” (Greek nous pathētikós or nous dynámei , Latin intellectus possibilis ) in the soul, but as an effecting intellect (later called intellectus agens in Latin) it is one of the body and also of the soul independent substance that comes in “from outside” and only thereby turns the possibility of human thought into a reality. This is how the human thought soul arises ( noētikḗ psychḗ or, especially under the aspect of its discursive activity, dianoētikḗ psychḗ ). It can absorb all forms. She does not gain her knowledge through recollection, as with Plato, but from the objects of sense perception by abstracting . The sensory perceptions and emotions, including affects that are also physically strong - anger is accompanied, for example, by a "boiling of the blood and the warmth around the heart" - are phenomena of the "sense soul" ( to aisthētikón or aisthētikḗ psychḗ , Latin anima sensitiva ).

For Aristotle, the soul is an immaterial form principle of living beings, the cause of movement, but itself unmoved. He localizes them in humans and the higher animal species with regard to all their functions in the heart. It controls all life processes via the warmth of life that is present in the entire body. The soul is passed on to the offspring through conception; it is already present in the seed.

The existence of body and soul, including the possible intellect, ends for Aristotle with death. The active intellect, on the other hand, is and remains separate from the physical organism and is therefore not affected by its death; he is incapable of suffering and imperishable. However, Aristotle does not derive any individual immortality from this.

Stoic

The Stoa , a school of philosophy founded in the late 4th century BC, developed its concept of the soul from a materialistic approach. A main source of the old Stoic doctrine of the soul are excerpts from a lost work by Chrysippos of Soloi , which was entitled About the Soul . Chrysippus was the third head of the Stoa school. His teaching is a further development of that of the school founder Zenon von Kition .

In contrast to Platonists and Peripatetics, the Stoics viewed the soul as physical (subtle). According to the Stoic doctrine, the whole world of sensually perceptible matter is pervaded by a fire-like substance, the pneuma . Zeno of Kition already assumed a rational, fiery cosmic soul that he called pneuma . The soul of an earthly living being (psyche) is in its entirety a special form of pneuma . The individual soul of man and animal arises between conception and birth, as the relatively dense pneuma is transformed into the finer quality of the psyche ; this process is completed at birth. Plants have no psyche ; their life is based on a different type of pneuma . The soul permeates the whole body, but always retains its own identity. In death it separates from the body. According to the old Stoic doctrine, it survives this separation, at least in some people, but is not immortal, but dissolves at a later point in time. There is no underworld as the realm of the dead, because the soul can only ascend because of its relative ease.

The peculiarity of the human soul is a “ruling part” (hēgemonikón) that carries out the activities of the intellect. According to the majority opinion of the Stoics, his seat is in the heart. From the hēgemonikón all emotional impulses and in general all psychological activity emanate . There all impressions are recorded and interpreted. In addition to the hēgemonikón, there are seven subordinate parts or functions: the five senses, the ability to speak and the ability to reproduce. In the context of this material theory of the soul, the Stoics interpreted the interaction between the soul and the body physically . They attributed it to the fact that the soul tenses and relaxes and thus exerts pressure on the body, whereupon it registers its resistance as counter pressure. The self-perception of the individual is based on this effect.

The early Stoics rejected the Platonic assumption of different soul parts with different or opposing, sometimes irrational tendencies. They countered her with the conviction that the ruling intellectual part of the soul, the hēgemonikón , was the unified authority that made all decisions. They explained unwanted and harmful emotions as malfunctions of the hēgemonikón , which stem from its incorrect assessments and consist in particular of exceeding the limits of what is appropriate. In this way the entire emotional life was reduced to rational processes in the soul. What appears as an emotional conflict is therefore only an expression of a wavering of reason in the question of which idea it should agree to. The Stoics drew the consequence from this to largely deny the animals mental functions.

These old stoic doctrines spread in the radical version from Chrysippus, but were already considerably modified in the middle period of the Stoa. So Panaitios of Rhodes taught in the 2nd century BC. That the soul dies with the body. His pupil Poseidonios represented the existence of the soul before the formation of the body and its persistence after death, but held fast to its transience. He gave it an irrational component. In the more recent Stoa of the Roman Empire, Seneca († 65) and Marcus Aurelius († 180) avoided a clear definition of what becomes of the soul at death, but it was also clear to these Stoics that the disembodied soul might persist limited in time and immortality is to be excluded.

Epicureans

Epicurus (342 / 341–271 / 270) also understood the soul as a material component of the physical organism within the framework of his consistent atomism , he considered it to be a body within the body. Therefore, in his philosophy, the science of the soul belongs to physics. He compared the soul matter with wind and heat and said that it is distributed over the entire body. Matter of the soul differs from gross matter by its finer quality. The Roman Epicurean Lucretius described it as a mixture of heat-like, air-like and wind-like atoms as well as a fourth type of atom, which enables the transmission of sensory perceptions to the mind. These atoms are smooth, round and particularly small and therefore more mobile than those of other matter. This explains the speed of thought. Lucretius described the chest as the place of mental activity. When death occurs, according to the Epicurean doctrine, the soul dissolves, as its atomic components dissipate quickly. The cohesion of soul matter is only possible through its presence in the body. Perception occurs because atoms are constantly being detached from the objects of perception, which correspond to the structure of their objects of origin and are therefore their images. They flow in all directions and thus also reach the perceiving soul, in which they generate corresponding impressions. Thus every mental change presupposes an atomic one. However , Epicurus rejected the general determinism that can be derived from such a world view; he attributed the atoms to slight, indeterminate deviations from the orbits which, according to physical law, they should follow, thus creating space for the idea that there is a coincidence.

Middle and Neo-Platonists

The influential Middle Platonists Numenios and the Neoplatonists called for a return to the original doctrine of Plato, emphasizing cosmology and the theory of the soul. In Neo-Platonism, the Platonic principle of understanding philosophical life as preparation for death - that is, for a post-death existence of the soul - was particularly emphasized. In late antiquity , the religious dimension of Platonism was in the foreground. Neoplatonism presented itself as a soul-related path of salvation and as such competed with Christianity. The pre-existence and immortality of the soul and the transmigration of souls as well as the goal of liberation from matter were key points of the Neoplatonic philosophy, as well as the origin of the soul from the immaterial, divine world and the possibility of its return to this home.

In some details, however, the opinions of the Neoplatonists diverged. Plotinus stuck to the Pythagorean view, also held by Plato, that animal and human souls are inherently identical. From his point of view, the differences between humans, animals and plants are only externalities that are related to the difference in their body shells; they reflect the respective time-dependent state of the souls. Consequently, he even maintained that human souls are by nature equal to the gods. In contrast, Iamblichus of Chalkis , Syrianos and the other late Neo-Platonists taught that the human soul is by nature different from the souls of unreasonable living beings and therefore incarnates only in human bodies. Iamblichus also rejected the doctrine of Plotinus, according to which the soul is constantly connected to the intelligible world during its stay in the body , since its uppermost part is always there. He considered this assumption to be incompatible with the experience that the soul experiences unhappiness in the body. Also Proklos this view Plotinus refused.

The Middle and Neoplatonists also developed the Platonic concept of the world soul. So Plotinus viewed the world soul as the third highest hypostasis in the hierarchical structure of total reality. In Plotin's model it stands below the One and the nous , the world reason, which has emerged from the One . The world soul “emerged” from the nous , which is not to be understood in a temporal sense, but metaphorically in the sense of a timeless ontological order. It belongs to the intelligible world as its lowest part. Immediately below that begins the sensually perceptible world, the world of “becoming and passing away”, on which the world soul acts. According to Plotinus, the world soul includes all individual souls. The universe is a unified living being, animated by it, from which the interconnectedness of all its parts results.

Mythology and art

In mythology , Psyche is only documented in literature in the 2nd century, as the main character in the story Amor and Psyche by the Roman writer Apuleius . There Psyche appears as a mortal king's daughter, who is abandoned by her husband, the god Amor . It is only after she has completed dangerous tasks, including a descent into the underworld, that she can be reunited with him and is accepted among the immortals. Whether the author's main concern was imaginative, humorous entertainment or a religious purification motif linked to the flight of the soul in Plato's Phaedrus , where psyche should be understood as an allegory of the human soul, is controversial in literary studies.

The motif of the connection between Cupid and Psyche is, however, much older. In the Greek visual arts , girls with bird wings (later also butterfly wings), which are probably to be seen as depictions of the psyche, have been playing alongside other winged Cupid figures since the 5th century BC. BC before. Occasionally, on paintings in Pompeii, Psyche appears with bat wings in connection with a passage in the Odyssey where the souls of the dead are compared with bats. In ancient times, depictions of the soul as a soul bird or butterfly were popular, especially as a moth. Vase painters often depicted the soul as an eidōlon , as a small winged or wingless figure of a deceased, mostly fluttering in the air or rushing through the air. Sometimes the motif of the soul in the form of a snake is found in art and literature; So Porphyry reports in his biography Plotinus about the death of the philosopher: "There a snake crept under the bed on which he was lying and slipped into a hole in the wall, and he gave up his ghost." Obviously here is the soul serpent meant.

The question of the seat of the soul

Even in ancient times, attempts were made to determine the seat of the soul in the body and also to localize individual psychological functions. Heraclitus compared the soul to a spider that sits in the middle of its web and, as soon as a fly breaks one of the threads, rushes towards it as if the damage in the web was causing it pain. Just like the spider, when a part of the body is injured, the soul goes there quickly as if the injury to the body were unbearable. Aristotle considered the brain to be bloodless and therefore believed that it could not play a role in the processing of sensory perceptions. He assumed that all nerves from the sensory organs and skin lead to the heart and that this is the seat of the soul and sensory perceptions. In the age of Hellenism, opinions diverged about the location of the control center (hēgemonikón) of mental processes; localization in the heart was advocated by a large part of the scholars, while others advocated the brain. As early as the 3rd century BC The anatomist Herophilos of Chalcedon examined the four cerebral ventricles ; he suspected the most important control center in the fourth (rearmost) ventricle.

A main representatives of the brain hypothesis was the famous physician Galen (2nd century), who argued anatomically. Although he said that the soul is in the brain, he did not locate it in the ventricular system and did not assign the individual intellectual activities to specific brain areas. This assignment is only attested in the late fourth century (Poseidonios of Byzantium, Nemesius of Emesa ). Nemesios referred to the two anterior ventricles as the organs that are responsible for the evaluation of sensory perception and imagination (phantastikón) , the middle as the organ of the mind (dianoētikón) and the rearmost as the organ of memory (mnēmoneutikón) . He argued that this could be seen in damage to individual ventricles, which in each case lead to a disruption or loss of the associated mental functions, and thus also explained various mental illnesses.

Judaism

Antiquity

In the Hebrew Bible, the Tanakh , “soul” and body represent aspects of the human being understood as a unity. The force that invigorates the body - in religious-scientific terminology the body soul or vital soul - is called nefesch (נפש), neschama or ru ' in the biblical Hebrew . oh (רוח). All three terms originally designate the breath. Neither nefesch nor neschama nor ru'ach is something specifically human; the three terms are also used for animals.

Neschama is the breath of life which, according to the Book of Genesis, God breathed into the nose of his earthly creature Adam, with which he made him a living being (nefesch) . The specific basic meaning of nefesch is "breath" and "airway", "throat" and, due to the lack of a conceptual distinction between the trachea and esophagus, also "throat", "throat". Therefore, the word also denotes the source of the desire associated with the ingestion of food (hunger and thirst, appetite and greed) and, in a broader sense, also the seat of other desires, passions and feelings such as thirst for revenge, longings and affection.

As the invigorating breath, Nefesch is the life force that leaves a person at death, and life that is threatened, risked or extinguished. In the broadest sense, nefesch also stands for the whole person including the body and then means “person” (also when counting people). Man does not have a nefesch , he is one and lives as a nefesch . Therefore, nefesch is also used as a substitute for a pronoun , for example in the meaning of "someone". The god YHWH has a nefesch by which he swears. It occurs twenty-one times in the Tanakh, but not in all of its parts. The physical carrier of the life force is the blood. Whether the word nefesch could even mean “corpse” is debatable. In any case, the usual rendering of the Tanach in older German translations with “Seele” is inappropriate. The Tanakh writes nefesh neither existence before the formation of the body nor immortality, and nefesh is nowhere detached from the body.

Ru'ach combines the meanings "breath", "wind" and "spirit". The relevant Hebrew expressions also include the word leb ("heart"). In addition to the physical organ, it also describes the life force, the seat of intellectual abilities and feelings, will and decisions and, in the broadest sense, the whole person.

Parts of the late, especially Hellenistic Judaism knew of a continued existence of humans after their earthly death, which for some of the authors had to be connected with a physical resurrection, while others thought of a soul detached from the body. A world judgment was described in which the dead are judged according to their works.

Two contradicting ideas coexisted in the scriptures of the Second Temple period and in Diaspora Judaism (before and after the destruction of the Temple in AD 70). The rabbinical theologians held very different views. On the one hand, the "soul" continued to be equated with life or person, on the other hand, educated Jews influenced by Greek took over from Platonism and the philosophical currents of Hellenism the conception of the soul as an independent being that existed independently of the body. Among them the view was widespread that the soul was of heavenly origin, the body of earthly origin. According to the report of the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, the Essenes assumed an immortal, subtle soul that lives in the body like in a prison and is liberated at death. The Pharisees believed in a resurrection, but the Sadducees denied immortality and resurrection.

The philosopher Philo of Alexandria , who was active in the early 1st century and was strongly influenced by Platonism, believed that the rational soul was destined for eternal life, but some souls were not able to fulfill this determination. Immortality does not naturally come from all souls, but is the reward for correct behavior during earthly life. Only the virtuous are granted eternity, for bad people the death of the body is connected with the extinction of their souls.

In Amoraic scholars acceptance of the pre-existence of the soul was added. Around AD 300, Rabbi Levi taught that God had consulted with souls before performing His work of creation.

Middle Ages and Modern Times

In medieval Jewish philosophy , from the 9th and 10th centuries ( Saadja ben Josef Gaon , Isaak Israeli ) under the formative influence of Platonism (now including Neoplatonism), which was later also received indirectly via Avicenna , the conviction of the Immortality of the soul, which Saadja combined with an emphatic belief in the resurrection. In particular, Jewish Neoplatonists of the 11th and 12th centuries, such as Solomon ibn Gabirol (Avicebron), Bachja ben Josef ibn Paquda , Abraham bar Chijja and Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra , pleaded for immortality . However, some Jewish philosophers of the Middle Ages did not understand immortality as an individual continued existence, but as the souls of the deceased merging into the spiritual world. They assumed that matter as the principle of individuation would disappear with death and that the individual soul could not continue its separate existence based on this principle without the body. The soul, which Saadja had still considered to be subtle, was generally understood as an incorporeal substance since the High Middle Ages ; their rational aspect was emphasized. The idea of immortality caused difficulties for the 12th century Aristotelians, Abraham ibn Daud (Abraham ben David Halevi) and Maimonides (Moshe ben Maimon), who viewed the soul in the Aristotelian sense as the form of the body. While Abraham ibn Daud believed that the soul arises with the body, but followed the Platonic view on the question of immortality, Maimonides differentiated between an innate, mortal soul and an acquired, rational soul that survives the body. Apparently Maimonides believed that the rational soul in the hereafter did not remain a separate individual but was absorbed in the divine active intellect, but he avoided formulating this clearly.

The Neoplatonic way of thinking was even more noticeable in the Kabbalah than with the medieval Jewish philosophers . There the pre-existence of the soul and the transmigration of souls (Hebrew gilgul ) were taught. According to a tradition presented in the book of Bahir , there are a fixed number of pre-existing souls. In the beginning they were all gathered in a place called guf , the place of souls waiting for their entry into a body. Since people are constantly being born, the guf empties in the course of time, until finally the story will come to its end by completely emptying the guf . However, this process is delayed by sin, because unclean souls have to go through the transmigration of souls for their purification. The transmigration of souls has occurred in Kabbalistic literature since the 12th century. In particular , it plays an important role in the Lurian Kabbalah founded by Isaak Luria (1534–1572), an influential movement in the following years.

Christianity

New Testament

In the New Testament , the Greek term ψυ kommt (psyche) occurs, which is rendered as "soul" in older Bible translations. Even in the Septuagint , the Greek-built by Jewish scholars Tanakh translation, the Hebrew term was נפש (nefesh) with psyche translated. In most of the passages in the Gospels where psyche is mentioned, “life” is meant in the sense of nefesch , specifically to denote the quality of a certain individual - human or animal - to be alive. Behind this is the traditional idea of a “life organ” connected to the breath and located in the throat. In this sense it is said that the psyche as the life of a person is threatened ( Mt 2,20 LUT ), for example through lack of food ( Mt 6,25 LUT ; Lk 12,22f. LUT ), or that it is withdrawn becomes ( Lk 12.20 LUT ) and is lost ( Mk 8.35-37 LUT ). The psyche is the seat and starting point of thinking, feeling and wanting. In the more recent translations of the Bible, psyche is not translated as “soul”, but as “life”, “man” or a personal pronoun. This holistic conception of man corresponds to the idea of a physical resurrection and a body-soul unity in the risen in the hereafter , which was already present in early Christianity . The resurrection of Jesus is understood as “taking up” the psyche that was previously “given up” ( Jn 10 : 17f. LUT ).

However, other passages show that the New Testament relationship between body and soul is complicated. The term psyche is fuzzy, in some places probably ambiguous, the transitions between its meanings are fluid. A change in meaning is recognizable: the development of language reflects the emergence of dualistic ideas of body and soul in the anthropology of Hellenistic Judaism. The psyche in the sense of the new, Hellenistic language usage exists - unlike the Old Testament nefesch - independent of the body and cannot be killed ( Mt 10.28 LUT ; see also Rev 6.9 LUT and Rev 20.4 LUT ). It is understood as a part of the human being that is opposite to the body. This shift in meaning can be explained by the influence of philosophical concepts of Greek origin. According to 1 Petr 3.19f. LUT , Jesus went - apparently between his death and his resurrection, i.e. without his body - to "spirits" imprisoned "in prison" who had disobeyed at the time of the flood , and preached to them. With “spirits” (Greek pneúmasin ) are probably meant here souls who have survived the death of their bodies and are in the underworld ( Sheol ); the statement is traditionally and also in more recent specialist literature related to the “ Hell's Descent of Christ ”, but the interpretation of the difficult passage is controversial. The fact that the gospel was preached to the dead - i.e. bodiless souls of deceased people - is communicated in 1 Pet 4,6 LUT . In Rev 6,9-11 LUT the visionary sees “the souls (psychás) of those who were slaughtered” and hears them calling out in a loud voice. Here the idea of a perception and ability to act of the souls that continue to live after the destruction of their bodies is assumed.

The apostle Paul uses the term psyche only eleven times in his letters and avoids it in statements about life after death. His idea of the soul is partly shaped by Jewish thought, partly by Greek philosophy and its terminology.

Epoch of the Church Fathers