History of Westphalia

The history of Westphalia deals with the development of this historical landscape in western Germany.

At the beginning of its history, the term Westphalia referred to as the settlement area of the Saxon sub-tribe of the "Westfalai", a reasonably clearly delimited historical area. In the Middle Ages and the early modern period there were strong cultural and linguistic similarities within this area, but politically it had been territorially divided since the early Middle Ages . Until the end of the old Duchy of Saxony (1180), the Saxon dukes did not succeed in creating a central political order. The Archbishops of Cologne , who as Dukes of Westphalia could only control a comparatively small area in the south, also failed as legal successors . The differences increased with the confessional division into Protestant and Catholic territories. The Napoleonic Kingdom of Westphalia used the name, but only included some areas that were considered Westphalian. It was only with the Prussian province of Westphalia that a unified political structure emerged. Like today's part of North Rhine-Westphalia , the province was significantly smaller than the “cultural Westphalia” of the early modern era.

prehistory

Hunters, gatherers and fishermen (for at least 300,000 years)

Homo heidelbergensis , Homo neanderthalensis

The hand ax from Bad Salzuflen is one of the oldest artefacts in Westphalia and dates back to 350,000 to 300,000 years ago. This is ascribed to the epoch of Homo heidelbergensis .

Much more recent finds in the area of Westphalia show the presence of Neanderthals during the Middle Paleolithic . In the Münsterland , the Ruhr area and the Sauerland , archaeological finds indicate hunting camps. In a sand pit near Warendorf , a small part of the skull of a Neanderthal man was found in conjunction with Moustérien tools. The 20 to 30 year old man died of meningitis. The Balver Cave is one of the most important sites of the Middle Paleolithic in Europe . Over four large layers were discovered here, which were deposited after several phases of use by groups of hunters over a period of around 50,000 years. During the Eem warm period around 126,000 to 115,000 years ago, the cave was first used by Neanderthals, who last wintered there around 40,000 years ago. Since during the last phase of the Vistula Ice Age the polar glaciation advanced very far south and the area of Westphalia became a cold steppe (tundra), the region was not habitable for a long time.

Late Paleolithic, anatomically modern man, groups of penknives and Ahrensberg culture

It was not until the late Paleolithic that reindeer hunters settled. There are many sites from the Mesolithic period. The oldest skeletal finds of anatomically modern people, which were discovered in the leaf cave near Hagen in 2004, also date from this time . Their age has been dated to more than 10,700 years by the C-14 method .

About 300,000 years ago the Megaloceros giganteus appeared in Westphalia , a giant deer of which about two dozen remains have been excavated in Westphalia, such as in the Emschertal in Herne . The antlers of the deer species that lived there during the entire Glaciation of the Vistula show signs of processing and were dated to 11,890 ± 147 cal BC . Similar traces of processing are found in antlers of the same species from Paderborn-Sande , dated 11,966 ± 177 cal BC. Hunters of the early penknife groups had apparently processed an antler rod. A barb tip from Bergkamen-Oberaden , today in the Gustav-Lübcke-Museum in Hamm , measures 25.3 cm; it may have come from an elk bone and has been determined to be 11,050 ± 110 cal BC. It's probably a fish picker, not a harpoon. The hunters and fishermen who made these tools belonged to the late penknife groups.

The Hohler Stein site near Rüthen - Kallenhardt (Soest district) is the only site of the Ahrensburg culture in Westphalia that belongs to the younger Dryas period , a final cold phase. Similar to before, the reindeer was the most important hunting animal. The hunters used the change of herds in the spring, when the animals moved to the low mountain range in order to give birth to their offspring and to avoid the mosquitoes for hunting. Two fragments could be dated to the time around 9894 ± 146 and 9947 ± 127 cal BC. A little later the reindeer herds disappeared from Westphalia.

Mesolithic

Datable artefacts from the Mesolithic, the post-Cold Age era of hunters and gatherers, are only found in Westphalia from the leaf cave near Hagen and the Werl-Büderich site discovered in 2011 (Soest district) and from Weitkamp in Oelde (Warendorf district, around 8000 BC .) known. Oelde-Weitkamp is the oldest Mesolithic site in Westphalia. The Riegersbusch site, east of Hagen-Eilpe , contained 700 stone artefacts that suggest connections to Brandenburg, but also to southern Germany. A piece of pasture belonging to the same find horizon could be dated to 8603 ± 40 cal BC. Using a piece of elk antler that was used as a tool, the almost simultaneous influence of the Maglemose culture of the north could be demonstrated (8993 ± 116 cal BC).

Neolithic: tillage, livestock farming (from approx. 5500 BC)

Transitional phase, pastoral and peasant cultures

In the 6th millennium BC The transition to agriculture and cattle breeding began mainly in the Hellweg area. The early transition from hunting, fishing and collecting to tillage and livestock farming of the Neolithic, due to the often sandy soils of Westphalia, can hardly be grasped; however, it is believed that it started much later than on the loess soils to the south. The late Mesolithic cultures Swifterbant and Ertebølle emerged further to the north, but they took over ceramics and livestock farming from the farmers of the south. The T-shaped antler axes made of red deer antlers were used by both end Mesolithic and Neolithic groups. About 20 of these tools are known from Westphalia, which have a shaft. Five of them can be dated to between about 5000 and 3600 cal BC. Only the second oldest find (4898 ± 42 cal BC), from the Schencking sand pit in Greven , can probably be attributed to Mesolithic people based on its age and location. The other pieces are more likely to belong to the Neolithic Rössen and Michelsberg cultures . From this it is concluded that the northern part of Westphalia was still clinging to the hunting traditions, even if innovations were adopted, while the southern part was already inhabited by farmers and shepherds.

Settlements of the Bandkeramik , Rössen and Michelsberg cultures are documented from the Neolithic Age . Burials of the older Neolithic cultures are not yet known from Westphalia. From the late Michelsberg culture, however, there are several particularly well-preserved skeletal remains of people from the leaf cavity near Hagen. They are among the very few known burials from this period in Europe.

So-called megalithic graves and burials of the cup cultures were found from later periods of the Neolithic period . The Hellwegbörden are the border area between the facilities of the funnel cup culture ( Halen, Heiden ) and the Hessian-Westphalian gallery graves of the Wartberg culture ( Calden , Warburg-Rimbeck ). The southernmost large stone grave in the Westphalian region can therefore be found near Altlünen on the Lippe. Between the areas of the funnel cup culture and the Wartberg culture, there was the Soest group , to which five megalithic systems belong, which began in 3700 BC. Were erected.

Numerous stone tools indicate that the people who lived in Westphalia during the Neolithic Age benefited from mining on flint and other raw materials. These raw materials and finished stone tools were transported over long distances. The Feuersteinstrasse refers to a kind of regular exchange with this equipment. In several settlements and graves in Westphalia, flint tools from the Maas , from Lousberg near Aachen and from France as well as slab horn stone from southern Germany ( flint mine from Abensberg-Arnhofen , Baiersdorf ) were discovered. Ax blades made of nephrite and jadeite come from the Alps , more precisely from the 3841 m high Monviso , from the Balkans and Bohemia the amphibolite , which was used in band ceramics and in the Rössen culture to make adze blades and wide wedges .

Metal times

The transition to the metal age was fluid. Objects made of copper played a role as grave goods, for example in the megalithic graves. A notable use of bronze took place since about the last third of the third millennium in the culture of the bell- beaker people and largely prevailed until the end of the millennium. Without their own deposits, they had to rely on the import of metal. Numerous imports from the North Sea region to the British Isles, but also from southern Germany and Spain, prove this. Therefore, the epochs mentioned elsewhere in Westphalia, the Copper and Bronze Ages, are assigned to the Neolithic.

In the second millennium, the culture in Westphalia was initially much more uniform than in the previous epoch. However, the lip eventually formed a cultural boundary again. While the dead were buried in stone chamber graves in the north, the urn field culture spread in the south . From the 8th century BC The bronze amphora comes from Gevelinghausen . Their Etruscan style elements document trade relations as far as the Mediterranean.

Gradually, during this time, preliminary stages of the later Celts and Teutons developed . In the Siegerland, for example, the Hallstatt culture dominated , while Pre-Germanic groups immigrated to northern Westphalia. The Hallstatt people began to exploit the iron ore deposits in the Westphalian mountainous region as well as the salt deposits on the Hellweg . For example, iron and salt became coveted export goods in exchange for amber. Bleicher even describes the Siegerland and South Westphalia as the "Ruhr area" of that time. During this time, the settlement focus shifted significantly to the south. Above all there a differentiated society developed with a class of aristocracy, larger estates, a Gauherrschaft and places of central importance.

Since around 250 BC Numerous refuges were built in BC , some of which may have been permanently populated. Oppidae influenced by the Celts in this sense were the Herlingsburg near Schieder (Lipper Bergland), a facility on the Wilzenberg in South Westphalia or the Aue Castle in the Wittgensteiner Land. Some of these complexes may also have had a supra-local cultic significance, such as the Istenberg complex near the Bruchhauser Steinen or the Wilzenberg.

Many of the castles were destroyed by the expansion of Germanic tribes, but mostly rebuilt soon. The Roman historians of the beginning of the imperial era counted all inhabitants of Westphalia as Germanic peoples. The dominated Brukterer in today's Munster country, Angrivarii and Cherusker in the Weser area, the Marsi and Chattuarier am Hellweg and Sauerland. Despite certain local differences, these tribes belonged to the Rhine-Weser Germanic tribes ( Istwäonen ).

Romans and Teutons

Since then Nero Claudius Drusus in 12 BC BC crossed the Rhine, a conflict began for almost thirty years for supremacy in Germania magna . The reasons are not clear. It is sometimes claimed that the Romans had a conquest as far as the Elbe in mind from the beginning. There is much to suggest that the origin of the conflict is to be found in initially limited punitive expeditions. Not least the alliance of the influential Cherusci, Suebi and Sugambrer tribes led to the expansion of the war to large parts of free Germania. The course of the river Lippe in the north-west was an important gateway for the Romans as a natural traffic route. It was no coincidence that Vetera (near today's Xanten ) was an important military camp on the left bank of the Rhine opposite the river mouth.

Various Roman camps bear witness to the attempts to gain a foothold on the other side of the Rhine . One of the earliest standing camps (11 BC) was near Oberaden ( Roman camp Oberaden with Beckinghausen subcamp ); it had room for two legions and their auxiliary troops . After the Drusus campaign against the Sugamber was successful, the focus of the war first shifted from Westphalia to the south, before it was directed against the Cherusci. The campaigns of Drusus were so successful that Germania was at times almost seen as a conquered province from the perspective of the Romans. For the Roman rule, even after Oberaden was surrendered, the Lippe and its camps formed the backbone of their rule. The most important was the Roman camp Haltern , consisting of a main camp, various forts and a port. Other camps were the Roman camp Holsterhausen , the Roman camp Olfen and the Roman camp Anreppen .

Around the year 1 there was an uprising of Germanic tribes, which was suppressed by Tiberius , the brother of Drusus, until about 5 AD. Significant for the Romans' certainty of victory was that with Publius Quinctilius Varus a man was appointed governor who had made a name for himself more as an administrative expert than as a military man. Under the leadership of the Cheruscan Arminius , there was again an alliance of the Germanic tribes in 9 AD and finally an open uprising, which ended in a catastrophe for the Romans in the Varus Battle . Since the 19th century at the latest, local historians from different parts of Westphalia have claimed to have localized the site of the battle. The Hermannsdenkmal near Detmold still bears witness to this today . Archaeological finds in the Kalkriese region near Bramsche (in the Osnabrück district ) show that the dispute may have taken place at a completely different location.

The attempt to expand Rome into the area of free Germania had in fact failed with this defeat, although the Romans also showed presence in the following decades with various, sometimes extensive, military expeditions - for example by Germanicus (14-16 AD). In contrast to the Rhineland with its Roman cities, the area of Westphalia remained an agricultural area.

middle Ages

Early middle ages

Saxon expansion

For a large part of the time between the Roman attempts at expansion and the end of the migration period , written sources about the development in the Westphalia area are largely lacking. This gradually changed during the era of the Merovingian kings. Theudebert I. claimed in a letter to the Eastern Roman emperor Justinian I in 534 that he exercised sovereignty over Saxon areas , but the letter served primarily propaganda purposes. A few decades later, Chlothar I reestablished the Saxons' temporarily refused tribute obligations with a campaign that reached as far as the Diemel River . With the increasing weakening of the Merovingian rulers, a power-political gap emerged, which the Saxons used to expand their sphere of rule. Over a long period of time, this did not take place primarily through conquest, but rather through a gradual union of local tribes, so that the Saxons were not a homogeneous tribe, but a people that had grown together from different groups. Towards the end of the 7th century, non-Saxon Germanic tribes, some of Frankish origin, such as the Brukterer , lived in this area . At its end there was the expansion of the Saxon area to the lower Ruhr (subjugation of the Brukterer 693/695). In contrast to the Christianized Franks, the majority of the Saxons still clung to their pagan faith. In the 8th century there were important Saxon centers in Westphalia. In Marklo , a place that cannot be identified with certainty, the central tribal assemblies were held (if one follows the Vita Lebuini , the only source). Saint Irminsul near Obermarsberg was the most important religious site of the Saxons.

According to the Saxon history ( Res gestae Saxonicae ) of Widukind von Corvey, the Saxons described by him were divided into the tribes of Westphalia, Engern and Ostfalen before the Saxon Wars of Charlemagne .

Saxon Wars of Charlemagne

The Franconian counter-reaction to the Saxon expansion began under Karl Martell and was continued by his successors. The conflicts with the expanding Franconian Empire under Charlemagne were also carried out in the region. The main opponent was Widukind at times . The Annales regni Francorum reports , among other things, of the conquest of the Syburg over the Ruhr in the south of today's Dortmund city area. In connection with a Saxon uprising in the area of Lübbecke 775, the term "Westphalia" appears for the first time in writing in the imperial annals of Charlemagne as a name for a Saxon sub-tribe. In the Saxon Wars , the Eresburg at what is now Marsberg 772 was conquered by Karl. The Irminsul was destroyed and a church was built in its place a few years later. At the Lippequellen ( Bad Lippspringe ), the Saxons submitted for the first time in 775/76. As a result, a fortified royal palace was built on the site of today's Paderborn . To celebrate the victory, a Frankish-Saxon imperial assembly and a synod took place there in 777 . However, the Saxons were not yet completely subjugated. There were riots on various occasions. The uprising of 782, which reached its climax with the Battle of the Süntel, ended with the mass executions of the Verden Blood Court . The turning point came in 785, when another Reichstag was held in Paderborn , Widukind submitted and was baptized. In the 790s there were uprisings again (794 battle on the Sintfeld near Bad Wünnenberg ). Afterwards, Westphalia was “pacified” from the perspective of the Franks.

Incorporation into the Franconian Reich Association and Christianization

At the demonstrative Reichstag of the victorious Franks in 799 in Paderborn, Westphalia, a meeting between Charlemagne and Pope Leo III took place. instead of. The Roman imperial coronation was agreed for the following year. The meeting was presented promptly in the Paderborn epic .

This was followed by the violent, systematic Christianization of Westphalia. Before the Frankish rule, missionaries like Suitbert or Bonifatius had mostly only had temporary success in non-Saxon areas. The Christian religion was then part of the rule strategy of the conquerors under Charlemagne. The basis for this was the establishment of a church organization. In the beginning there was the division of the Saxon area into mission districts and the appointment of bishops. The first bishop of Münster was Liudger , from whose cathedral castle the later city emerged. Further bishopric seats were Osnabrück , Minden and Paderborn. The Archbishop of Cologne was responsible for the Christianization of the Sauerland and Hellweg area. Founding monasteries should also further consolidate the Christian religion. One of the first monasteries was founded in Obermarsberg . Corvey , Werden and the Herford Abbey in particular developed into rich and powerful monasteries and were cultural and religious centers. Other early monasteries were founded by Böddeken by Meinolf , Vreden , Freckenhorst , Meschede , Liesborn , Nottuln and Schildesche, who were later canonized .

The establishment of parishes was more important for the implementation of the new religion among the population. Wormbach (near Schmallenberg ), Soest , Dortmund and in the far east Geseke are among the oldest original parishes in Cologne's area of responsibility . In the diocese of Münster it was next to the episcopal city of Rheine , the original parishes of Ibbenbüren , Bünde and Wiedenbrück belonged to the diocese of Osnabrück , in the diocese of Paderborn it was apart from the episcopal city of Eresburg ( Marsberg ) and Steinheim .

After the final crushing of the Saxon resistance, Westphalia, as part of the Duchy of Saxony, belonged to the sphere of power of the Carolingian empire from the end of the 8th century . Although the Saxon nobility was not eliminated, the area also had its own legal source with the Lex Saxonum , but the self-government by the traditional things was wiped out, and since the Reichstag in Lippspringe (782) the land was part of the judicial and administrative units of the Divided counties. Since there was only a small amount of royal property in Westphalia , the count's constitution was inevitably based on the possessions of the local nobility. In addition, however, there were quite a few royal courts. There were Pfalzen about the Eresburg, Herstelle and Paderborn.

Westphalia in Ottonian and Salian times

Although Ludwig the German held a Reichstag twice in Paderborn, Westphalia itself was on the verge of political development. Within this space, of course, far-reaching and long-lasting developments took place. While in other parts of the East Franconian Empire the decline of royal power was partially compensated for by the rise of new, strong duchies, this development largely failed to materialize in Westphalia. Although the area was part of the Duchy of Saxony , its rulers only had a relatively small influence in the southern part of their area. This is also reflected in its title: " dux orientalium Saxonum " (Duke of East Saxony). But King Heinrich I , who also remained Duke of Saxony as King, was able to expand his influence in Westphalia by marrying the later sanctified Mathilde from Enger . For the subsequent Ottonian kings , the Hellweg and the Royal Palace of Dortmund were an important link between the Rhine and the ancestral seat of the Ottonians.

After the transfer of royal dignity to the Salians , Westphalia fell even more clearly on the sidelines. The result was that various count families, other territorial lords and, increasingly, ecclesiastical dignitaries began to pursue independent policies in their areas and tried to expand their property at the expense of their neighbors. The first most important and strongest count house was that of the Counts of Werl . Their possessions stretched from present-day Schleswig-Holstein in the north to the Sauerland in the south, and as reeves in the diocese of Paderborn they also had considerable influence outside of their actual territory. Their importance is also shown in marital connections with the royal family and other noble families.

High and late Middle Ages

Imperial and Territorial Policy

From the second half of the 11th century, imperial politics began to have more direct consequences for Westphalia. This is how the suppression of the Otto von Northeim uprising in 1073 took place in southern Westphalia. The royal troops stormed the castle on the Desenberg near Warburg and devastated the neighboring areas of the Paderborner Land and the Sauerland. The violent clashes in connection with the investiture dispute between Heinrich IV and the rival king Rudolf von Rheinfelden (1077) were partly carried out on Westphalian territory. The Count stood Werl who are after their move to Arnsberg as counts of Arnsberg designated on the imperial side. Also in connection with the dispute between the emperor and the pope, the archbishops of Mainz and Cologne allied themselves in 1112 with the new Saxon Duke Lothar von Süpplingenburg against Heinrich V. The rebels defeated the emperor in the battle of the Welfesholz . Then Lothar turned to the diocese of Münster, which had remained loyal to the emperor, and conquered the bishopric of Münster.

Dortmund with its royal palace was fortified in 1113 by order of Heinrich V, but destroyed in October 1114 by Lothar von Süpplingenburg and his allies. In the following year Heinrich was able to recapture royal Dortmund and fortify it again.

Count Friedrich von Arnsberg, one of the most powerful Westphalian aristocrats of the time, changed fronts on various occasions and in some cases lost a considerable part of his dominion in these political contexts. Both Lothar and the Archbishop of Cologne were able to successfully conquer castles in Arnsberg. After the death of Friedrich the strong position of the Werl-Arnsberg counts was broken.

Another powerful family with a tendency towards territorial formation were the Counts of Cappenberg an der Lippe. Not least their relatives with the Hohenstaufen - Otto von Cappenberg was godfather of the future King Friedrich I - as well as their vast estates gave them power and influence. In addition to numerous upper courts in Westphalia, for example in and around Cappenberg on the Lippe, in Mengede on the Emscher, in Varlar, Coesfeld and on the Lower Rhine, the Cappenbergers also had rich properties in the Wetterau and Swabia. A change occurred when Count Otto and Gottfried von Cappenberg , the latter married to Ida , daughter of Friedrich von Arnsberg, under the influence of Norbert von Xanten, handed over their property to the Premonstratensian order and entered the Cappenberg Monastery, which was newly founded . The subordination of Cappenberg to the Bishop of Münster, which was associated with the founding of the monastery, strengthened the episcopal position on the Lippe considerably.

The strongest forces have been since the reign of Lothar III. thus the bishops of Munster, Paderborn and Minden. The following centuries in southern Westphalia were marked by the expansion of the Archbishops of Cologne. After the disempowerment of the Saxon Duke Henry the Lion by Friedrich Barbarossa (1180), the ducal dignity was divided in Saxony. In the Gelnhausen document it was determined that the part of the duchy east of the Weser should fall to the Ascanians ; Duke of Westphalia and Engern became the archbishop of Cologne, at that time Philip I of Heinsberg . His nominal territory included the South Westphalia belonging to the Cologne diocese and the diocese of Paderborn . The diocese of Münster was not mentioned.

But in Paderborn, too, the people of Cologne had no direct power. The area ruled directly by the archbishop as the Duchy of Westphalia was initially a relatively small area around Werl , Rüthen and Brilon vom Hellweg ( Erwitte and Geseke ) along the Möhne , as well as Medebach , Winterberg and Attendorn in the Sauerland. It had come into the direct possession of the Archbishops of Cologne since 1102 and was largely transferred from the possessions of Henry the Lion in 1180. Later the area continued to grow through various acquisitions. The development came to an end with the donation of the County of Arnsberg in 1368 by the last Count Gottfried IV. As early as 1228, the Cologne bishops had taken over the rule in Vest Recklinghausen . The two Westphalian territories of the Cologne residents were geographically far apart and were administered separately.

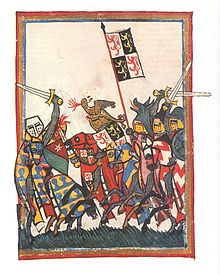

Although the archbishops exercised ducal power for the whole of Westphalia as defined, the political power of the individual territories was divided between counts and bishops. The county of Mark experienced a special development with its territory in South Westphalia. Their rulers managed to expand their territory considerably. Since the interests of the counts repeatedly overlapped with those of the Cologne Erzstuhl, the competition between Mark and Cologne shaped the development in southern Westphalia for almost two hundred years. Foreign powers, in particular the Dukes of Burgundy as allies of the Counts of the Mark, also played a not inconsiderable role. The Battle of Worringen in 1288 largely ended the expansion of the Cologne population, while the Counts of the Mark now clearly assumed the leading role.

Territorialization in the late Middle Ages

Especially between the late 13th and the end of the 15th century, Westphalia was characterized by the rise of smaller or larger clerical or secular rule, which were able to develop their areas into territorial states with more or less success. The Münster Hochstift laid the foundations for the Niederstift (outside the later Prussian province of Westphalia). Within this area, most of the smaller lordships fell to the diocese, which had been a largely closed area since the 15th century. Only Steinfurt , Gemen and Anholt remained independent . However, the diocese was during the Munster collegiate feud (1450-1457) again the plaything of foreign interests (Cologne Archbishops, Counts of the Mark, Counts of Hoya , Dukes of Burgundy), who disputed over the occupation of the bishopric.

The Principality of Paderborn was under pressure from the Archbishops of Cologne for a long time (there were attacks on the diocese border on Hellweg between Geseke and Salzkotten for several centuries ) before Cologne's defeat in the Battle of Worringen put an end to this. In the first half of the 14th century Paderborn acquired the remains of the possessions of the formerly important Counts of Schwalenberg . Inside, the bishops succeeded in restricting the power of the Lords of Büren .

The Minden bishopric was in a significantly worse position, and surrounded by powerful neighbors such as the Counts of Schaumburg and the Dukes of Braunschweig , it could hardly expand. While the ecclesiastical jurisdiction extended to the Lüneburg Heath , the secular territory was much smaller. It almost coincided with today's Minden-Lübbecke district .

The Counts von der Mark acquired numerous areas in southern Westphalia and on Hellweg. Their area finally included roughly the area of today's cities of Hagen , Bochum and Herne , large parts of today's Dortmund city area, the parts of the city of Hamm and the Unna district south of the Lippe , the area of the Ennepe-Ruhr district , the south of the Emscher parts of the city of Gelsenkirchen and the district of Recklinghausen , Soest with its Börde and most of today's Brandenburg district . The Counts of the Mark inherited the County of Kleve and united them for the first time in 1398. Inheritance disputes within the house led to armed conflicts between the main heir of the two counties Adolf II and his brother Gerhard. Gerhard prevailed in large parts of the county, but was only allowed to call himself Graf zur Mark and his brother formally retained suzerainty. Only after the death of Gerhard (1461) were the two territories finally united. In 1417 Emperor Sigismund raised Adolf II to the rank of duke.

In addition to the county of Mark, the counties of Ravensberg and Tecklenburg were the most important secular domains in Westphalia. The Counts of Ravensberg acquired Enger as pledge around 1408 and gained secular sovereignty over Herford Abbey . However, after the death of the last count in 1437, Ravensberg fell to the dukes of Jülich .

In 1521, the Jülich-Berg (including Ravensberg) and Kleve-Mark areas were finally united, and the Mark House gained considerable power in the empire. The so-called United Duchies reached their greatest territorial extent between 1538 and 1543. At that time they consisted of the duchies of Jülich , Kleve , Berg , Geldern , the counties of Mark , Ravensberg , Zutphen and the rule of Ravenstein and the Lippstadt condominium . This shifted the power of the Westphalian noble family from the Mark further to the west. As early as 1391, the house had moved its main residence from Hamm in Westphalia to Schwanenburg in Kleve.

Westphalian cities

City emergence and founding of cities

A certain counter-movement to the formation of territory was associated with the emergence of the medieval city and an urban self-confidence. While the cities of the Rhineland were often in the direct or indirect tradition of the cities of the Roman Empire , there had been no cities in the Saxon Westphalia. The oldest cities here were the bishops of Osnabrück, Münster, Paderborn and Minden; later Dortmund and Soest were added as well as numerous other cities.

The largest city in the 15th century was Soest with 10,000 to 12,000 inhabitants, followed by Dortmund and Münster with 7,000 to 9,000 inhabitants and Paderborn and Minden with around 4,000 inhabitants each. A bourgeois self-confidence soon developed here. The citizens of Münster exercised the right to collect taxes as early as 1180 and the bishop left the city in 1278 and has since resided at Wolbeck Castle . Hardly any different in Paderborn, where the bishop left the city after disputes with the citizens in 1275 and settled in Neuhaus .

A settlement gradually developed around Dortmund's imperial palace, and a market must have existed by the end of the 10th century at the latest. A city wall existed in 1150. In the middle of the 12th century, Konrad III. Dortmund's city rights, which were confirmed by Emperor Friedrich II in 1236 . From the beginning, Dortmund was subordinate to neither a bishop nor a secular ruler other than the emperor, making it the only imperial city in Westphalia. Against the attempt to restrict the sovereignty of the city, Dortmund was able to prevail at the end of the 14th century in the Great Dortmund Feud against military attacks by the neighboring county of Mark and the Archdiocese of Cologne.

In contrast, Soest, as part of the Duchy of Westphalia, was initially under the rule of the Archbishops of Cologne. Around 1100 there was a permanent market and market jurisdiction in Soest. In the first half of the 12th century, the Soest town charter was already established , which was subsequently adopted by around 60 Westphalian cities, but also by Lübeck . Soest broke away from the domination of the Archbishop of Cologne during the Soest feud from 1444 to 1449 and submitted to the county of Mark.

The above-mentioned oldest Westphalian cities had in common that they did not go back to a founding act, but developed from small settlements based on bishopric or royal seats. Geseke , Höxter , Herford and Medebach were created in a similar way . In addition, numerous cities were laid out by the respective territorial lords, especially in the 13th century. Early examples are Lippstadt (1185), Lemgo (before 1200) and Rheda, founded by the Lippian counts. During this phase, the Archbishops of Cologne expanded Werl into a city, while Brilon , Rüthen , Geseke and Attendorn were also expanded into cities at the beginning of the 13th century. In the diocese of Münster, Coesfeld and Warendorf can be traced back to older settlements that were elevated to the status of towns towards the end of the 12th century. The same applies to Ahlen , Beckum , Bocholt and Telgte (all with city rights until 1240). In the Diocese of Paderborn, urban development did not begin so much with the bishops, but with local aristocratic families as in Warburg , Büren and Brakel . The Counts of Arnsberg granted the Arnsberg settlement below their castle in 1237 city rights.

The city of Hamm is a special case among the city foundations of the Middle Ages in Westphalia , the founding of Hamm goes back to an imperial political event, the assassination of Cologne Archbishop and Imperial Administrator Engelbert I of Cologne in 1225 by his relative Friederich von Altena-Isenberg . Count Friedrich von Altena-Isenberg was braided on the bike for this outrage , his possessions of castle and city of Nienbrügge as well as his Isenburg near Hattingen were destroyed as atonement. Adolf I. Count von Altena-Mark , also a relative of Friedrich and the murdered Engelbert, now took the side of the archbishopric and thus came into possession of most of the Altena-Isenberg inheritance. After the execution of the judgment in Nienbrügge, he settled the homeless Nienbrügge just a few hundred meters upstream at the confluence of the Lippe and Ahse rivers in his new planned town . On Ash Wednesday 1226, the count granted her the town charter derived from Lippstadt law .

The Counts of Ravensberg raised Bielefeld to town in 1214 . While the older founding cities often resembled the models of the grown cities as trading and industrial cities, the city foundations between 1240 and 1290 were significantly smaller and long-distance trade played only a minor role. The cities founded after 1290 mostly belonged to the type of consciously created minor cities . Depending on the region, these are called Wigbolde, Freedom or Spots, and although they had essentially city-like rights, mostly no city wall and their exterior and internal structure could hardly be distinguished from larger villages.

City federations and Hanseatic League

The development of urban alliances was characteristic of the development of urban self-confidence . To protect the merchants, Münster , Osnabrück , Coesfeld , Minden and Herford joined the Ladbergen City Association in 1246 , while Soest, Dortmund, Münster and Lippstadt joined forces in 1253 in the so-called Werner Bund . A year later, numerous Westphalian cities joined the Rhenish Federation . By the 14th century at the latest, the cities had overtaken the old counties economically through long-distance trade and specialized handicrafts.

This economic importance is shown not least in the participation of Westphalian cities in the Hanseatic League . A total of around 80 present-day Westphalian cities and municipalities claim to be part of the Hanseatic League. Admittedly, the quality of this membership varied widely. The most important and most active Hanseatic cities were Dortmund, Soest, Münster and Osnabrück, which at that time still belonged to Westphalia. Dortmund initially functioned as the suburb of the so-called “Westphalian-Prussian third”, before this position was temporarily and permanently transferred to Cologne. A few other cities also played a certain role. In addition to such cities, which were invited to the Hanseatic Days, there were numerous auxiliary cities that had trade privileges but could not have a say within the Hanseatic League. In the 16th century , these included Bielefeld , Herford and Minden. Wiedenbrück was an auxiliary town of Osnabrück , Munster had Coesfeld, Rheine, Warendorf , Borken , Bocholt , Dülmen , Haltern , Ahlen , Beckum , Werne and Telgte as auxiliary towns, and Soest included Lippstadt, Arnsberg, Werl, Rüthen, Brilon and Geseke . There were also Paderborn and Warburg. Hamm and Unna rose from Dortmund's beist cities to principal cities, which in turn now claimed Kamen , Lünen , Schwerte , Iserlohn , Lüdenscheid , Breckerfeld , Altena , Neuenrade , Plettenberg , Bochum , Hattingen , Wattenscheid , Wetter , Blankenstein , Westhofen and Hörde as additional cities. Back then there were only Essen , Dorsten and Recklinghausen behind Dortmund . In addition, there were numerous places associated with the Hanseatic League, which in turn were assigned to the Beistädten. At this point in time, the Hanseatic League had long since passed.

Victims courts, knight associations and estates

Not only the expansion of the cities but also other factors limited the rule of the sovereigns. In the area of jurisdiction, the sovereign Gogerichte competed with the Westphalian females courts , especially in the 14th and 15th centuries . These courts could arise because on the one hand there was no real ducal power in Westphalia and on the other hand the existing courts were often ineffective. The Vote Courts, which were originally responsible for the quite large number of personally free residents of Westphalia, were increasingly used by outsiders over the years.

The behavior of parts of the knighthood and the nobility shows that the late medieval territory was not yet a complete state in the modern sense . In the 14th century, knight associations such as the Benglerbund were formed in the border area between the Duchy of Westphalia and Hesse . Even if these partly pursued political goals, they were more like robber knights .

The creation of estates was of greater importance in the long term . In the Duchy of Westphalia, for example, the archbishops of Cologne were forced to enter into agreements ( hereditary associations ) with the nobility and cities several times in the 15th century . This led to the creation of state parliaments , which can be documented in the Duchy of Westphalia until 1482. The assembly was divided into the knight and city curia. The development in other territories was similar, even if the composition could differ. In the spiritual areas this mostly included the rural nobility and clergy. The mass of peasants was rarely represented. The most important right was undoubtedly the annual tax permit. In the spiritual areas, bishops were also forced to "surrender by election" before taking office, which above all guaranteed the rights and privileges of the estates.

Early modern times and religious wars

Westphalian Imperial Circle

In the course of the imperial reform of Maximilian I , new imperial circles were formed at the Reichstag in Cologne in 1512 . These were responsible for the election of representatives in the Reich Regiment , the Reich Chamber of Commerce and, since the Reich Execution Code, also for securing the peace , peacekeeping and the coin police. The Lower Rhine-Westphalian Empire was also among the imperial circles . It comprised the areas from the East Frisian North Sea coast, via the Lower Rhine, Münsterland to the Sauerland, roughly the areas from the Weser to the Maas. Of the Westphalian territories, these included: the counties of Mark and Ravensberg, Steinfurt, Bentheim and Lippe . In addition, there were the spiritual areas of Osnabrück, Münster, Minden, Paderborn, Corvey, Herford and the Verden an der Aller monastery (it was considered the northeasternmost area of the Westphalian Empire and protrudes into the Lower Saxony Empire), as well as the cities of Dortmund, Soest and Herford . As part of the Electorate of Cologne, the Duchy of Westphalia and Vest Recklinghausen belonged to the Kurfürstendamm district.

Reformation and Counter-Reformation in the cities and territories

Humanism and Urban Reformation

The Reformation was initially an "urban event" ( English , "urban event"; Arthur Geoffrey Dickens). In principle, this also applies to Westphalia. The forerunners of the Reformation were the Catholic reform movements of the 15th century, such as the “ Devotio moderna ”, which were also important in Westphalia. There were corresponding frater houses in Münster (1401) and Herford (1428). There were monasteries of the Augustinian hermits (the order to which Martin Luther also belonged) in Herford and Lippstadt. The prehistory also includes the spread of the Renaissance (the Weser Renaissance style developed in Westphalia ), humanism and the establishment of book printing . There were also educated humanist circles in Westphalia. One of them was the Münster canon Rudolf von Langen , who, in the spirit of humanism , helped the old cathedral school, today's Paulinum grammar school , to regain its reputation. In Münster, this also includes Jacob Montanus , who was a follower of the Devotio moderna. As early as 1521 he opened up to reformist ideas and was in close correspondence with Luther and Melanchthon . The same applies to the Münster high school teacher Adolf Clarenbach , who was burned as a heretic in Cologne in 1529, and to Johann Glandorf , who eventually went to Wittenberg .

The starting point for the Reformation in Westphalia was the Fraterhaus der Devotio moderna in Herford and the monasteries of the Augustinian hermits. The “Lippstadt Catechism” of 1534 ( Johann Westermann ) is the first independent Westphalian Reformation testimony. The first Reformation sermons were given in Herford as early as 1521. These mixed up with social conflicts, which finally led to the acceptance of craftsmen in the city council in 1525. However, the Reformation was not implemented in the city until around 1530. From 1525 it also gained a foothold in Dortmund. In Osnabrück the Reformation took on sometimes violent traits around this time. Reformation movements followed a little later in Soest. There Protestant visual ethics found expression in Heinrich Aldegrever's engravings . The revolt of the craftsmen of 1531 was decisive for the city. With the exception of the Patroklistift , all parish churches became Protestant and in 1532 the Soest church ordinance was issued. It was created under the direction of Gerd Omeken , who had previously organized services in Lippstadt "na gebruke der Hilligen Wittembergische Kerken". With the Archigymnasium , a central Protestant educational institution was established in 1533. Johannes Gropper , one of the most important Westphalian theologians of the Counter-Reformation of the 16th century , came from the Patroklistift .

Somewhat unusual was Iserlohn's reformer Johannes Varnhagen , who was neither a humanist nor a devotee of the Devotio moderna, but had studied at the strictly Catholic University of Cologne before he preached in Iserlohn in a Protestant sense from 1526. In this city, however, it took until 1558 before the Reformation really took hold. At times the religious renewal movement was also quite successful in Paderborn. There there was a social uprising in 1528, as a result of which the Reformation ideas spread. The height of its importance was already reached in 1532 when the new bishop Hermann von Wied suppressed the movement and forbade the Reformation.

Prince Reformation and Counter Reformation

The events in Paderborn reflected a fundamental change in the Reformation not only in Westphalia. Success and failure were no longer determined by autonomous urban movements, but by the will of the respective sovereign. Due to the feudal influence of the Hessian Landgrave Philip I , Protestantism was enforced in the Wittgenstein counties . In the Siegerland , too , the Reformation was mainly promoted by Count Wilhelm I of Nassau-Dillenburg . While Protestantism prevailed in the Mark, Bergisches Land and Minden-Ravensberg regions, these attempts failed in the spiritual territories of the dioceses of Paderborn and Münster. How strongly the denomination was dependent on the respective sovereign is shown by the example of the Duchy of Westphalia. This area, as a property of Cologne, was about to change its denomination when two archbishops converted to Protestantism. In the case of Hermann von Wied , the defeat of the Protestants in the Schmalkaldic War and the archbishop's resignation (1547) put an end to this development. Forty years later, Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg's reformatory intentions could only be ended by the war in Cologne and Gebhard's defeat (1588).

On the other hand, Calvinism was able to gain a foothold in some parts of Westphalia in the 17th century because part of the nobility felt addressed by this variant of Protestantism. The relationship to the already Calvinist Netherlands played a considerable role. So the Counts von der Lippe or Count Arnold II. Von Bentheim converted to the Reformed faith. In the county of Siegen, too, the sovereigns turned to the teachings of Calvin and the Nassau-Dillenburgs even became the political supremacy of Calvinism in the empire after the Electoral Palatinate returned to the Lutheran creed.

The territories of Westphalia that remained Catholic were shaped by the Counter Reformation in the 16th and 17th centuries. This term from the 18th century comes from the Iserlohn legal scholar Johann Stephan Pütter . Important intellectual and spiritual supporters of the Counter-Reformation in Westphalia were the Jesuits , who maintained some important settlements in politically important cities such as Arnsberg or Münster. As the driving force behind the spread of the Catholic faith, this and other orders - such as the Premonstratensians or Minorites - contributed to the reform or establishment of grammar schools. This included the Paulinum grammar school in Münster, later also the Laurentianum grammar school in Arnsberg and the Petrinum grammar school in Brilon.

On the other hand, humanistic schools emerged in Minden, Soest, Osnabrück and Dortmund, which also served to spread the Reformation. Some Calvinist sovereigns also founded new educational institutes, which on the one hand were committed to humanistic ideals, but on the other hand also served to consolidate the faith. This included the high school in Burgsteinfurt in today's Steinfurt . This played an important role in education for reformed north-west Germany and the neighboring Netherlands.

The special case: The Anabaptist Empire in Münster

The Anabaptist Empire in Münster was an extremely special case both in Westphalia and in Europe as a whole . At first, the development proceeded essentially according to the usual patterns of the city reformation. The humanistic and reformation-friendly endeavors mixed with social movements in 1525. Added to this was the political autonomy of the citizens against the episcopal sovereign as a further factor. In the early 1530s , most of the parish churches joined the Reformation, while the cathedral and a few others remained true to the old faith.

The Anabaptists were a radical Reformation movement that had found a broad following, especially in what is now the Netherlands, and which differed in key points from Protestantism of Lutheran provenance. The Anabaptists rejected the baptism of underage children as unbiblical and advocated adult baptism. The Münster variety of Anabaptism influenced by Melchior Hofmann also had a pronounced end-time character . The end of the world was expected soon and Munster was seen as the New Jerusalem .

The dominance of the Anabaptists in the city was primarily due to the influx from outside (besides the Wassenberg predicants , especially Jan Matthys and Jan Beuckelsson - better known as Jan van Leyden ). But before that, Bernd Rothmann , the reformer of Münster, had opened up to Anabaptist ideas. In addition to the charisma of Jan Matthys in particular, this contributed to the acceptance of the new teaching among many of the residents of Münster. Above all, the influential cloth merchant Bernd Knipperdolling made himself an advocate for the Anabaptists. After the flight of numerous Catholics and Lutherans, the Anabaptists succeeded in electing the council to gain power in the city in a formally legal way. Later, in place of the council, the "order of the twelve elders" was set under the "prophet" Jan Matthys and finally Jan van Leiden as "king". During the reign of the Anabaptists community of property and polygamy were introduced and violent excesses occurred.

It was only after the troops of Bishop Franz von Waldeck and his allies had besieged the city for a year that Münster was recaptured after treason. Gruesome executions of the leaders of the Anabaptist movement followed. The Reformation movement in Münster was finally defeated, and the prince-bishopric of Münster remained a Catholic area for a long time.

Admittedly there were followers of Anabaptism in some other Westphalian cities as well, but these remained a marginal phenomenon, especially after the end of the Anabaptist Empire. As a rule, politically active Anabaptists were expelled from the cities. As an exception to this rule, Peter von Rulsem was executed in Dortmund in 1558 , an Anabaptist who refused to give up his missionary work.

Thirty Years' War

Westphalia was also included in the international conflicts that were also connected with the religious split. This applies, for example, to the effects of the Eighty Years' War between the Netherlands and Spain. In the winter of 1598/99 , Spanish troops occupied large parts of the region. Ambrosio Spinola then tried in 1605 and 1606 to restore Spanish hegemony on the Lower Rhine and in the western part of Westphalia.

The Thirty Years' War began for Westphalia in 1621, when the Protestant general Christian von Braunschweig transferred troops first to Ravensberg and at the end of 1621 to the Prince Diocese of Paderborn and began to raise contributions. A year later, the Spanish troops in Lippstadt were driven out by the Protestants and Christian von Braunschweig made Lippstadt the base of operations against the cities of Soest, Geseke and Paderborn. Geseke was the only one that could not be taken. In Paderborn, among other things, the cathedral treasure fell into his hands. He also undertook prey actions against the Münsterland before he withdrew to the Main in May 1622 (June: Battle of Höchst).

In the autumn of 1622 counter-actions by the Catholic League followed . Their general Johann Jakob von Bronckhorst zu Anholt had his base in the Duchy of Westphalia and raised high contributions in this Catholic region before he could recapture the lost territories after Christian's departure from Braunschweig. This gave the Catholic troops a free hand in Westphalia and in turn occupied numerous Protestant cities in the county of Mark. The returned Bishop Ferdinand of Bavaria organized a criminal court in Paderborn . In 1623 the troops returned from Braunschweig and the two armies plundered and pillaged the cities of the other denomination. In the same year there was the first great battle of the war in Westphalia, when the Catholic general Tilly, together with von Bronckhorst, inflicted a devastating defeat on Christian von Braunschweig's troops in the battle of Stadtlohn (August 6). It was characteristic of the character of the war that the Catholic armed forces plundered monasteries and monasteries in western Münsterland on a large scale in search of booty. In October 1623, the city of Lippstadt held by Christian von Braunschweig had to capitulate; Catholic troops then moved into Ravensberg and Minden. The first phase of the war, the Bohemian-Palatinate War , ended in Westphalia with a clear victory for the Catholic troops.

In the Danish-Lower Saxon war that followed, there were some advances by the Protestants, but these essentially ended with the death of Christian of Braunschweig in 1626. After the victories of Tilly and Wallenstein in the same year against the Danish king Christian IV and his allies, he was emperor Ferdinand II at the height of his power. One consequence was the attempt to recatholicize. In Westphalia, Elector Ferdinand of Bavaria was entrusted with this task. These efforts ended when the Swedes entered the war in 1630. In Westphalia, the Protestant Wilhelm V of Hessen-Kassel took over the initiative, who was awarded the monasteries of Münster and Paderborn and the Corvey Abbey by the Swedish king Gustav Adolf . Wilhelm tried to incorporate these Westphalian areas into Hesse. The main rival on the Catholic side at this time was Count Gottfried Heinrich zu Papenheim .

The Westphalian cities on Hellweg were particularly badly affected by the destruction and looting of the Thirty Years' War during this phase. Dortmund was repeatedly forced by Catholic as well as Protestant troops to give high cash benefits because of its wealth. The imperial city, which was independent of territorial lords, remained tolerant of Lutheran and Catholic residents. For several months in 1632 the troops of the imperial commander Pappenheim took quarters in Dortmund. Pappenheim, too, refrained from burning the city down only for a ransom. Soest in the Brandenburg region suffered similarly from the war and the smaller cities such as Bochum, Hattingen, Recklinghausen and Paderborn were also affected. The rural land was plundered again and again.

Militarily, victories and defeats alternated on both sides; By 1634 at the latest, the height of Hessian power had passed. Various cities such as Brilon, Rheine, Vreden and Bocholt were lost by 1635. Further losses followed a year later. With French support, the Hessian operations continued, but in 1641 the Hessians with Lippstadt and Dorsten had lost their most important bulwarks. In the following years there were still some skirmishes and looting (e.g. Obermarsberg destroyed in 1646 ), but basically nothing changed on the front line.

In contrast, the cathedral, which is far away from the wide Hellweg road, was largely spared the chaos of war. The north-Westphalian city was threatened by Hessian troops only once, but not seriously damaged. Due to its intactness, the city - with Osnabrück - was one of the few places where the peace negotiations could take place at the end of the war, although the Spanish ambassadors in particular repeatedly commented on the provinciality of the conference venue.

On October 24, 1648 , the Peace of Westphalia was concluded in Münster and Osnabrück . He ended the Thirty Years War and established a new political system in Europe. The peace was a pan-European event, but it also had an impact on Westphalia. This concerned about the determination of the denominational map (the status of the year 1624 was taken as a basis). The secularization of the Minden bishopric and its transition to the Electorate of Brandenburg , which was able to expand its Westphalian possessions and its influence in the region, was important for Westphalia . Otherwise hardly anything changed in the existence of the Westphalian territories.

Witch hunts

The belief in witches reached its peak in the 16th and 17th centuries. In parts of Westphalia, the witch hunt was particularly intense. In the county of Lippe and in the city of Lemgo 430 people fell victim to the witch hunts. There were also many victims in Vest Recklinghausen, the Hochstift Paderborn, and in Westphalia in the Electorate of Cologne ( witch hunt in the Duchy of Westphalia ). 900 people were burned in witch trials in this area . There were particularly many executions in Bilstein , Fredeburg, Geseke , Hallenberg , Menden , Oberkirchen , Rüthen, Minden , Herford and Werl. The trials in the duchy reached their peak during the Thirty Years' War, 600 trials are known from the years 1628 to 1631 alone. 280 people were executed in Balve during this time. In the duchy, the processes were not primarily based on popular belief, but on state authority. Above all, Elector Ferdinand of Bavaria and Landdrost Kaspar von Fürstenberg pushed the trials forward. On their behalf, legally educated people worked as witch commissioners and judges . These included Franz Buirmann and Heinrich von Schultheiß . This also gave a reason for the alleged necessity of the persecutions in a published paper. Of course, criticism of witch trials and torture was made early on in Westphalia too . The critics included Johann Weyer , Anton Praetorius , Hermann Löher and Michael Stappert . Friedrich Spee became particularly well known for his Cautio criminalis font . The last executions took place in the Duchy of Westphalia in Geseke in 1708 and in Winterberg in 1728; a last witch trial ended in 1732 in Brilon with an acquittal.

Westphalia in the 18th century

In the 18th century, Westphalia remained a territorially divided area. What they had in common was belonging to the Holy Roman Empire . Its imperial courts in particular (the Reichshofrat and the Reichskammergericht ) still played an important role for Westphalia. For example, the peasants of the Wittgenstein rule between 1696 and 1803 repeatedly and successfully litigated their sovereigns who tried to curtail peasant rights.

Even if the Holy Roman Empire continued to exist, its political institutions lost weight. After the Thirty Years' War, the significance of the Lower Rhine-Westphalian Imperial Circle decreased more and more. The religious differences played an important role. Central, however, was the influence of powers outside Westphalia, especially Brandenburg-Prussia , which began in the 16th century . District meetings took place only rarely, and the right to mint, which had previously been part of the Reichskreis, was transferred to the individual areas. The district military constitution, as prescribed by the Reich Defense Order of 1681, actually no longer played a role. Larger district estates (especially Brandenburg-Prussia), as armored estates, took over the military duties towards the empire, even for smaller, non- armored rulers in return for an annual payment. This tied smaller areas politically and militarily to the larger states and alienated them from the empire. Such areas close to Prussia were the Reichsstift Essen , the Reichsabtei Werden , the imperial city of Dortmund and the county of Limburg . Overall, the 18th century was marked by a deep split into a Protestant-Prussian and a Catholic part.

The Prussian-Protestant Westphalia

In Westphalia, Prussia owned the counties of Mark and Ravensberg, the secularized monastery of Minden and the county of Tecklenburg . The Duchy of Kleve was also directly adjacent to Westphalia . These areas were part of Prussia, which rose as an absolutist state in the 18th century to join the group of major European powers. Especially under Friedrich Wilhelm I , the class elements were pushed back more and the individual areas were more and more clearly combined into a state. Since 1723 there was a central administrative authority with subordinate war and domain chambers with the General-Oberfinanz-War and Domain Direktorium . The chamber in Kleve was initially responsible for the county of Mark , before a Brandenburg chamber was set up in Hamm in 1787 . The most famous president was Baron vom Stein since 1793 . The corresponding facility in Minden was responsible for Minden and Ravensberg. Districts with district administrators were set up below these institutions and replaced the administrative constitution that was previously common in Westphalia. In addition, the previous municipal self-government was largely eliminated. In addition, with the excise tax , the Prussian government had an indirect tax that was independent of the estates.

The government's efforts to regulate were also expanded internally. In the county of Mark, for example, the so-called management principle applied to the local coal and iron mines , which guaranteed the influence of the authorities, guaranteed the rights of miners and severely curtailed entrepreneurial freedom. This contributed to the economic development under the sign of mercantilism .

Prussia's hallmark in the 18th century was undoubtedly its strong army. The most important garrison towns in Prussian Westphalia were Hamm, Minden and Bielefeld. Wesel was the strongest fortress in the entire Lower Rhine-Westphalian area .

The Catholic Westphalia of the spiritual states

The territories of Catholic Westphalia differed significantly from Prussian Westphalia, but also from the other contemporary spiritual states. While in the southern German clerical states the co-rulership of the estates was largely eliminated in the 18th century , it continued to play a major role in Westphalia. This restricted the sovereign leeway to a considerable extent. This was especially true for the state parliaments' right to obtain tax permits . The character of an electoral principality also severely restricted the possibilities for an absolutist mode of rule. The cathedral chapters played a central role. They negotiated an election surrender with the future sovereign - a guarantee of traditional rights and a kind of government program.

The abundance of power of the ecclesiastical rulers seems at first glance to be impressive, especially through the administration of various spiritual states in personal union. So was Clemens August I of the House of Wittelsbach archbishop of Cologne and sovereign in Vest Recklinghausen and in the Duchy of Westphalia, in addition he was also Bishop of Munster, Paderborn, Hildesheim and Osnabrück. His successors Maximilian Friedrich von Königsegg-Rothenfels and Maximilian Franz von Austria were also chief shepherds from Cologne and Münster. The self-portrayal hardly differed from contemporary secular rulers. This was expressed in their buildings, for example. Clemens August had the secondary residence in Arnsberg rebuilt by the architect Johann Conrad Schlaun . His successor Maximilian Friedrich had the prince-bishop's palace built in Münster by the same master builder .

Nevertheless, there was no real consolidation of this personal concentration of power. Clemens August did not succeed in establishing an authority over all areas based on the Prussian model. The appearance of the absolutist ruler largely concealed the reality of the estate.

Age of Enlightenment in Westphalia

Gradually a new form of public arose with the creation of magazines and newspapers. The Lippstädter Zeitung was created as early as 1710 . In 1766 an intelligence paper for the Duchy of Westphalia was founded in Arnsberg . Since 1784 the magazine Westphälisches Magazin on geography, history and statistics appeared in Bielefeld. In 1793 Arnold Mallinckrodt began publishing a newspaper in Dortmund, which after various title changes later became known as the Westfälischer Anzeiger .

Masonic lodges , which made a major contribution to the spread of Enlightenment ideas, were established in Münster, Minden, Bielefeld, Bochum, Hamm, Hagen, Schwelm and Iserlohn since 1778 . The Lodge at the three bars in Münster remained the only one in Catholic Westphalia.

In the spiritual states of Westphalia, the so-called “Catholic Enlightenment” played an important role. Criticism of the dominance of the Roman Curia and the splendid appearance of Baroque Catholicism played an important role. The Catholic Enlightenment was primarily a current in contemporary theology. However, it also played an important role in the actions of princes and statesmen.

Especially towards the end of the 18th century, leading ministers such as Franz von Fürstenberg in the Diocese of Münster and Franz Wilhelm von Spiegel in the Duchy of Westphalia and in Kurköln sought reforms in the spirit of the Enlightenment . In the Hochstift Paderborn, however, the success of the reform movement was low. The attempt by Spiegels to abolish the monasteries failed of course due to the concentrated resistance of the clergy and the nobility. The reformers were more successful in education. In addition to reorganizing the two grammar schools Laurentianum in Arnsberg and Petrinum in Brilon , Friedrich Adolf Sauer was entrusted with the reorganization of teacher training and so-called industrial schools were set up according to reform pedagogical concepts at the time . In Münster, the university founded in 1780 and the Paulinum grammar school belonged to this context. Von Spiegel had already done the same a few years earlier for the Electoral Cologne countries at the University of Bonn .

Similar developments, especially with regard to the reform of the educational system, also occurred in Protestant-Prussian Westphalia. Here, too, teacher seminars were set up - for example in Petershagen (1792), school regulations were issued and the grammar schools were reformed.

Westphalia in the Seven Years War

Westphalia had not been a theater of war since the end of the Thirty Years' War in 1648, even if some princes were directly or indirectly involved in foreign armed conflicts. This changed dramatically with the Seven Years' War . Westphalia now became a scene of clashes between Austria, Russia and France on the one hand and Prussia and Great Britain / Hanover on the other. In 1757 the battle of Hastenbeck (near Hameln) between the French and the British took place under the command of the Duke of Cumberland . As a result, with the surrender of Kloster Zeven, France temporarily dominated all of north-west Germany and thus also Westphalia. After the defeat at Roßbach in Saxony , however, the French could not hold their position. After various twists and turns, they were defeated on August 1, 1759 in the battle of Minden by the troops of the Prussian general Ferdinand von Braunschweig . As a result, the fortunes of war turned again and Prussia was repulsed by the French at Kamp monastery ( Kamp-Lintfort ) on October 16, 1760. The last and decisive battle on the Lower Rhine-Westphalian theater of war took place on July 16, 1761 near Vellinghausen (Soest district). In the two-day battle, von Braunschweig won with 70,000 men against two French armies with a total of 110,000 men. In addition to the major battles, there were numerous other troop movements and clashes, in one of which Arnsberg Castle was completely destroyed by artillery fire in 1762. The civilian war damage was also considerable. It is estimated that in Minden-Ravensberg the population losses were 10% and in Grafschaft Mark 14%.

The end of the old empire and the kingdom of Westphalia

In the medium term, the French Revolution of 1789 also resulted in the end of the old Westphalia, which was split up into many small and medium-sized dominions. At first, however, statements about the revolution were rare from a Westphalian perspective. The former Premonstratensian canon Friedrich Georg Pape from the Sauerland belonged to the Jacobins of the Mainz Republic, but was not politically active in the region. The rumors spread by Pape about a Jacobin club in Munster have already been refuted by contemporaries. Rural and urban unrest remained rare. In the Hochstift Paderborn and in the city of Paderborn, freedom trees were erected in 1792 with the inscription: “Dear Citizens! Finally shake your yoke from yourselves and swear to be free by this tree. "

For many Westphalians, the numerous royalist emigrants were their first contact with the effects of the revolution. Especially after the advance of the revolutionary army in Belgium and the Netherlands in 1792, thousands of priests and nobles fled to Westphalia. In Münster alone there were 400 refugees in 1794. In 1792, the later French kings, Louis XVIII. (then Count of Provence) and Karl X. (Count of Artois) admission. There they were busy setting up a counter-revolutionary army of emigrants.

| Area and population of some Westphalian territories around 1800 | |||||

| Territories | Area in km² | population | Population density (inh. Per km²) | Urban population in% | Rural population in% |

| Minden-Ravensberg | 2.113 | 160.301 | 74 | 15th | 85 |

| County mark | 2,631 | 138.197 | 53 | 30.3 | 69.7 |

| County of Tecklenburg | 412 | 20,047 | 49 | 10.2 | 89.8 |

| prussia. Areas total | 5,886 | 340,000 | 54 | - | - |

| Monastery of Münster | 10,500 | 311,341 | 30th | 21.8 | 78.2 |

| Paderborn Monastery | 2.405 | 96,000 | 40 | 29 | 71 |

| Duchy of Westphalia | 3,854 | 125,000 | 33 | 29 | 71 |

| spiritual territories (total) | 19,576 | 720,000 | 37 | - | - |

| County Lippe | 1,215 | 70,849 | 58 | 18.6 | 81.4 |

| Dortmund (city and county) | 78 | 6,434 | 83 | 75 | 26th |

| Westphalia as a whole | 29,300 | 1,230,000 | 42 | - | - |

| Source: | |||||

The end of the spiritual states

The French occupation of the Rhineland (1794) was also of greater importance for Westphalia. The Kurkölner state was essentially merged with its Westphalian possessions (Vest Recklinghausen and Duchy of Westphalia). The Bonn officials, the court and the cathedral chapter fled mainly to the duchy. The Arnsberg monastery in Wedinghausen became the seat of the cathedral chapter and the repository of the relics of the Three Kings ; the highest courts found accommodation in the Landsberger Hof , while the government fled to Brilon . After the Peace of Campo Formio in 1797, the Rhenish area of the electoral state was formally annexed by France.

In Arnsberg, Archduke Anton Viktor of Austria was elected Archbishop of Austria in 1801 , but was no longer recognized politically, since with the Peace of Luneville everything boiled down to the secularization of the clergy, which was carried out in 1803 with the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss . As compensation for the losses on the left bank of the Rhine, the Kingdom of Prussia was awarded several abbeys, the Hochstift Paderborn and eastern parts of the Oberstift Münster with the city of Münster. The Munsteric office of Dülmen fell to the Duke of Croy , the Munsteric offices of Ahaus and Bocholt to two lines of the Princes of Salm , who established the Principality of Salm there. Other parts fell to other noble houses, most of which had hardly had any possessions in Westphalia. The Duchy of Westphalia went to the Landgrave of Hesse-Darmstadt and Vest Recklinghausen to the Duchy of Arenberg-Meppen . The Corvey Abbey and the imperial city of Dortmund became the property of the House of Orange-Nassau . As a result, as in the former Duchy of Westphalia, some of the monasteries and monasteries were secularized.

Grand Duchy of Berg, Kingdom of Westphalia and the Rhine Confederation reforms

The system of now exclusively secular territories created in 1803 did not last long in this form. After the defeat at Jena and Auerstedt by Napoleon I , Prussia suffered heavy losses in the Peace of Tilsit, especially in the west. In 1807 Napoleon founded the Kingdom of Westphalia with his brother Jérôme as king. The new kingdom with the capital Kassel comprised most of the former West Elbe areas of Prussia, parts of Hesse-Kassel , the bishopric of Osnabrück and the Hanoverian duchies of Göttingen and Grubenhagen . In Westphalia, in addition to a few smaller areas, Minden and Ravensberg as well as the former bishopric Paderborn belonged to the new kingdom.

The County of Mark, the Prussian part of Lippstadt , the County of Tecklenburg and the Prussian part of the former bishopric of Münster as well as the city of Dortmund fell to the Grand Duchy of Berg , whose Grand Duke Joachim Murat was appointed . There were also the County of Limburg and the Lordship of Rheda . At the end of 1810, France was forced to enforce the continental barrier and annex large parts of north-west Germany. The Principality of Salm , the jointly ruled territory of the Princely Houses Salm-Salm and Salm-Kyrburg, and the Duchy of Arenberg were incorporated into the French Empire. The Grand Duchy of Berg and the Kingdom of Westphalia also had to cede parts of their territories to France. The city of Münster was now part of France, while Bielefeld remained with the Kingdom of Westphalia.

Since 1806 the Westphalian areas in the French sphere of influence, but also the Duchy of Westphalia belonging to Hesse, belonged to the Rhine Confederation . A number of reforms were carried out in these areas, particularly against the class traditions. The co-government of the estates was abolished in many places, but the court and administrative regulations were also modernized. Tax reforms eliminated the privileges of the nobility. Agrarian reforms such as the unlimited divisibility of the land and the liberation of the peasants were initiated. The compulsory guild was lifted in the cities. In the Duchy of Westphalia, local self-government was also largely eliminated by the Hessian authorities. One has rightly spoken of a phase of “made up absolutism” for this area. The Kingdom of Westphalia was one step further with the promulgation of a constitution based on the model of the French constitution of 1799. In Westphalia, these reforms were the decisive break between the ancien régime and modern developments. It was not until 1815 that the Prussian reforms were introduced in Westphalia - with major modifications - some of which lagged behind the Rhine Confederation reforms in scope.

The various wars of Napoleon after 1807 cost numerous Westphalian soldiers their lives. Of the soldiers recruited from the Duchy of Westphalia alone, 1,400 soldiers and officers died in the Spanish theater of war by 1814. Units from Westphalia also took part in the Russian campaign. Hesse-Darmstadt left 5,000 men to Napoleon, a considerable number of whom came from the Duchy of Westphalia. After the battle of the Beresina , 30 officers and 240 men were left. 27 soldiers from the Medebach office took part in the Russian campaign, none of whom came home.

With the wars of freedom of 1813, the Napoleonic system of rule quickly collapsed in Westphalia. In November of that year, large parts of the Grand Duchy of Berg were occupied by the Prussian military. The civil government for the countries between the Weser and Rhine was established in Münster under Ludwig Freiherr von Vincke relatively soon . This laid the foundation for the Prussian province of Westphalia , founded in 1816 .

Prussian Province of Westphalia

It was not until the Prussian province of Westphalia that a unified political structure emerged from 1815/16. Like today's part of North Rhine-Westphalia , the province was significantly smaller than the “cultural Westphalia” of the early modern era.

The province of Westphalia consisted of an almost closed area and was administratively divided into the administrative districts of Arnsberg , Minden and Münster . It essentially comprised the districts of Minden, which belonged to Prussia before 1800, the counties of Mark and Ravensberg, Tecklenburg and the bishoprics of Münster and Paderborn, which came to Prussia after 1803, as well as some smaller dominions, including the counties of Nassau-Siegen and Limburg / Lenne . In 1816 the Duchy of Westphalia was added and the Essen district was incorporated into the Rhine Province . In 1851 and also during the Weimar Republic , the borders of the province were changed slightly. The provincial capital and seat of the chief president was Münster.

Against this background, a Westphalian self-image developed more strongly than before in the 19th and 20th centuries - also supported by the state authorities. However, this was always in competition with the nation-state, regional and local traditions. Some of the territories not integrated into the Prussian province, which had long been part of the Westphalian cultural area, remained independent parts of the German Confederation and, like the states of Oldenburg and Lippe, formed their own federal states of the German Empire after 1871 . Identification with Westphalia decreased in them in the 19th and 20th centuries, instead a strong, independent national awareness developed instead.

In the new province, the Catholic and Protestant areas were united. The Prussian authorities were faced with considerable challenges, particularly with the integration of Catholic Westphalia. A very different political culture in the Protestant and Catholic areas speaks for the long-term effect of the denominational split well into the 20th century.

The development of the province during the 19th century was shaped by the industrial rise of the Westphalian Ruhr area and the associated differentiation between town and country.

In the 20th century one can only rudimentarily speak of an independent Westphalian history, since the development in this area primarily reflects the processes in Germany as a whole.

During the Weimar Republic, inflation , the war on the Ruhr or major disputes between employers or employees such as the Ruhreisenstreit and the consequences of the global economic crisis also affected the industrial areas of Westphalia. During the time of National Socialism , the province has been politically into line and led no significant own life anymore. As in all of Germany, opponents of the regime, Jewish residents and the disabled were persecuted and killed. During the Second World War , Jews from Westphalia were also transported to the extermination camps. In the second half of the war in particular, the province was the target of Allied bombings in the course of the air raids on the Ruhr area and, in the last months of the war, the scene of ground fighting.