kk Standschützen

Standschützen were rifle guilds and rifle companies that had existed since the 15th and 16th centuries and repeatedly intervened in acts of war, initially only within and later also outside the borders of Tyrol. A rifleman was a member of a rifle stand at which he was rolled up, with which he committed himself to the voluntary military protection of the state of Tyrol (or Vorarlberg ) at the same time . Even when the regular military was stationed in Tyrol and Vorarlberg, the voluntary Standschützen were called in, for example in the First Coalition War in 1796/1797, in the Revolution of 1848/49 in the Austrian Empire , in the Sardinian War of 1859 and in the German War of 1866. High point In military engagement, however, until then there was undoubtedly the struggle for freedom under Andreas Hofer against the Bavarian and French occupiers, which culminated in the Battle of Bergisel , as well as the mobilization on the occasion of the First World War.

The roots of the Standschützen can be found in the Landlibell of Emperor Maximilian I from 1511 and a decree of Archduchess Claudia de 'Medici from 1632, in which each Tyrolean judicial district was obliged to set up a number of voluntary, defensive men, to be determined depending on the threat to provide a Landwehr.

development

At the end of the 19th century, the standing rifle companies, which had previously acted independently, were taken into the care of the military, who promoted and supported them as bodies useful for national defense . The now officially so called Standschützen were given the opportunity to practice target shooting under better conditions than before, in order to be prepared for home defense in an emergency.

With the National Defense Act of 1887 it was determined that the National Defense Institute was now to be regarded as part of the armed force and was divided into the Standschützen, supplemented by the shooting range, and the Landsturm .

With the provisions (§ 17) of the State Defense Act for Tyrol and Vorarlberg of May 25, 1913 and the law regarding the shooting range ordinance (same date), the shooting ranges (or the members who were rolled up) and all other bodies of a military character (veterans and warriors' associations) Landsturm obligatory. From this point on, every registered rifleman was subject to the duty to land storms; he was no longer to be regarded as a volunteer. Only the riflemen who joined the shooting range after the mobilization still carried the rating “volunteer”. Leaving the shooting range was prevented by law from August 1914. According to the Hague Convention , the Standschützen were from then on as regular troops. They were only allowed to be used in their own country and to defend the national borders. However, this was no longer observed in the final years of the war.

construction

A shooting range could be set up by at least 20 eligible male persons from one or more neighboring villages. Every Tyrolean and Vorarlberger who had reached the age of 17 and was physically and mentally suitable for shooting was entitled. It was mandatory for every member to take part in at least four exercises per year and to fire at least 60 shots according to a training plan for each exercise. The shooting range had no military significance in peacetime.

The Standschützen had the right to choose their officers themselves (note by the author and so tradition - which was a thorn in the side of many active officers.) The people first elected the officers in their entirety, which first of all meant the rank of lieutenant. The officers elected in this way elected the captains as company commanders from among their number , and these, with the highest rank of standing riflemen, selected the major as battalion commanders. Since Andreas Hofer was also only a major rifleman and no one should be placed above him. The result of the election had to be submitted to the military command and "Most High" confirmed. Only in the rarest of cases was a rejection made, as in the case of a Standschützen officer who had been sentenced to six months' imprisonment and demoted years earlier.

The officers of the Standschützen were ranked after the batches of the regular army and a command of the Standschützen was ranked equivalent to the command of the army, even if this was commanded by a lower rank.

The officers of the Standschützen wore badges of distinction , the star rosettes of the military officials in gold embroidery on grass-green Parolis, with the badges analogous to the other members of the branch.

There were a total of 65,000 riflemen at 444 shooting ranges in North , East , South and Western Tyrol .

Installation and supplementary locations

| battalion | Companies |

|---|---|

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion No. IX Auer | 1. Comp. Auer / Aldein / Radein - 2. Comp. Laives / Branzoll - 3. Comp. Neumarkt / Salurn - 4. Comp. Deutschnofen / Petersberg - 5. Comp. Montan / Truden |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion No. I Bozen | 1. Comp. Bozen - 2. Comp. Bozen - 3. Comp. Renon |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion No. IV Brixen | 1st Comp. Brixen - 2nd Comp. Brixen / St. Andrä - 3rd company Neustift / Vahrn / Natz - 4th company Lüsen / Afers |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Enneberg | 1st Comp. Bruneck - 2nd Comp. Enneberg - 3rd Comp. St.Leonhard / Abtei - 4th Comp. Buchenstein / Cortina |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Glurns | 1st Standschützen Company - 2nd Standschützen Company - 3rd Standschützen Company - 4th Standschützen Company |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Gries | 1. Comp. Gries - 2. Comp. Jenesien / Afing - 3. Comp. Terlan / Andrian / Vilpan / Mölten / Flaas |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Val Gardena | 1. Comp. Ortisei - 2. Comp. Selva - 3. Comp. St. Christina |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Imst | 1st Standschützen Company - 2nd Standschützen Company - 3rd Standschützen Company |

| kk Standschützen Battalion Innsbruck I | 1. Comp. Innsbruck - 2. Comp. Innsbruck - 3. Comp. Innsbruck - 4. Comp. Innsbruck - 5. Comp. Hötting |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Innsbruck II | 1st Comp. Hall - 2nd Comp. Stubaital - 3rd Comp. Wipptal |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Innsbruck III (Telfs) | 1st company Telfs - 2nd company Inzing |

| kk Standschützen Battalion Kaltern I | 1st Comp. Eppan - 2nd Comp. Kaltern |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Kaltern II | 1st company Margreid - 2nd company Kurtatsch - 3rd company Tramin |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion No. II Castelrotto | 1. Comp. Castelrotto - 2. Comp. Seis am Schlern - 3. Comp. Völs - 4. Comp. Barbian |

| kk Standschützen Battalion Kitzbühel | 1. Comp. Kitzbühel - 2. Comp. Hopfgarten - 3. Comp. Brixen im Thale - 4. Comp. Fieberbrunn |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion No. III Klausen | 1. Comp. Klausen - 2. Comp. Feldthurns / Latzfons - 3. Comp. Lajen - 4. Comp. Gufidaun / Villnöss / Theis |

| kk Standschützen Battalion Kufstein | 1st Comp. Kufstein - 2nd Comp. Ellmau / Scheffau - 3rd Comp. Langkampfen / Kirchbichl - 4th Comp. Thiersee / Ebbs |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Lana | 1. Comp. Lana - 2. Comp. Völlian / Tisens / Nals |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Landeck | 1. Comp. Landeck - 2. Comp. Stanzertal - 3. Comp. Paznauntal |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Lienz | 1st company Lienz - 2nd company Nußdorf - 3rd company Matrei - 4th company Huben |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion No. X Meran I | 1st comp. Meran / (main shooting range) - 2nd comp. Meran (reservists) - 3rd comp. Dorf Tirol - 4th comp. Meran (veterans) |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion No. VI Meran II | 1. Comp. Schenna / Riffian / Tall - 2. Comp. Algund - 3. Comp. Partschins - 4. Comp. Naturns |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Meran III | 1. Comp. Obermais / Untermais - 2. Comp. Marling / Tscherms - 3. Comp. Burgstall / Gargazon / Avelengo / Verano |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Nauders -Ried | 1st company Ried - 2nd company Reschen - 3rd company Graun |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion No. VII Passeier | 1st company St. Martin - 2nd company St. Leonhard - 3rd company Moos - 4th company Platt / Pfelders |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Prad | 1st Comp. Prad - 2nd Comp. Laas - 3rd Comp. Tschengls - 4th Comp. Lichtenberg |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Rattenberg | 1st company Alpbach / Brixlegg - 2nd company Brandenberg |

| kk Standschützen Battalion Reutte I | 1st company Reutte - 2nd company Berwang / Bichlbach - 3rd company Lermoos / Ehrwald |

| kk Standschützen Battalion Reutte II | 1st company Steeg / Bach - 2nd company Häselgehr / Forchach - 3rd company Nesselwängle / Jungholz |

| kk Standschützen Battalion Sarnthein | 1. Comp. Sarnthein - 2. Comp. Pens |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Schlanders | 1st Comp. Silandro - 2nd Comp. Kortsch - 3rd Comp. Martell - 4th Comp. Latsch - 5th Comp. Tartsch - 6th Comp. Kastelbell - 7th Comp. Tabland - 8th Comp. Schnals |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Schwaz | 1st company Schwaz - 2nd company Jenbach |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Sillian | 1st Comp. Sillian - 2nd Comp. Lesachtal - 3rd Comp. Sesto - 4th Comp. Toblach |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Silz | 1st company Silz - 2nd company Oetz - 3rd company Umhausen - 4th company Haiming (Tyrol) |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Sterzing | 1st Standschützen Company - 2nd Standschützen Company - 3rd Standschützen Company - 4th Standschützen Company |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Ulten | 1st company St. Pankraz / Pawigl - 2nd company St. Walburg / Proveis - 3rd company St. Nikolaus / St. Gertraud |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Monguelfo | 1. Comp. Vintl - 2. Comp. Sand in Taufers - 3. Comp. Welsberg |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Welschnofen | 1st Comp. Welschnofen - 2nd Comp. Tiers / Karneid - 3rd Comp. Ritten / Rentsch - 4th Comp. St. Nikolaus in Eggen |

| kk Standschützen Battalion Zillertal | 1st Comp. Mayrhofen / Brandberg - 2nd Comp. Mittleres Zillertal / Stumm |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Company | Stilfs |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Company | Taufers |

Welschtirol

| I. | II. |

|---|---|

|

|

| battalion | Companies |

|---|---|

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Cavalese | 1. Comp. Predazzo - 2. Comp. Cavalese - 3. Comp. Altrei - 4. Comp. Primör |

| kk Standschützen Battalion Cles | 1st Comp. Cles - 2nd Comp. Taio - 3rd Comp. Fondo - 4th Comp. Flavon - 5th Comp. Brez - 6th Comp. Proveis / Laurein |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Malè | 1st Comp. Rabbi - 2nd Comp. Caldes - 3rd Comp. Malè |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Trento |

Vorarlberg

| battalion | Companies |

|---|---|

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Bezau | 1st company Bezau - 2nd company Mittelberg - 3rd company Lingenau / Hittisau |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Bludenz | 1st company Walgau - 2nd company Klostertal - 3rd company Montafon |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Bregenz | 1st company Bregenz - 2nd company Wolfurt / Kennelbach / Hard - 3rd company Sulzberg - 4th company Alberschwende |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Dornbirn | 1st Comp. Dornbirn - 2nd Comp. Lustenau - 3rd Comp. Hohenems - 4th Comp. Höchst / Fußach |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion No. 4 Feldkirch | 1st company Feldkirch - 2nd company Frastanz - 3rd company Altenstadt / Gisingen |

| Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Rankweil | 1st company Rankweil - 2nd company Götzis - 3rd company Sulz / Röthis |

First World War

First effects

With the beginning of the First World War , the three regiments of the state riflemen were transferred to the Russian front, although, according to the law, they could only have been used to defend Tyrol . In Tyrol there were therefore only two fully-fledged battalions (Xth Marching Battalion of Infantry Regiment 59 and the Tyrolean Landsturm Battalion I ) available to protect the border against Italy. Another 19 battalions were only partially operational. The National Defense Command of Tyrol soon mistrusted Italy's neutrality and began, since the standing riflemen who were required to be held in reserve had already been called up and were therefore no longer available, to accelerate the military training of the remaining standing riflemen who were not required to be military.

For this purpose z. B. invalid or other retired Kaiserjäger or state riflemen are used. The training took place in the national costume or in a rifle skirt, and the men had to bring their own socks . The first deployments consisted of guard duty on military objects and on bridges or the like. Since uniforms were not yet available, black and yellow armbands were put on. Especially the younger, not yet regularly military trained, but also the older, whose military service was decades ago, caused the leadership a headache with regard to the military appearance. The youngest of these Standschützen was 14 years old, the oldest over 80 years. Because of these deficiencies, many active officers did not take the Standschützen seriously for a long time, and often treated them from above or even insulted them. That was not surprising, since suddenly there were majors, so to speak, in no time at all, whereas a normal officer only reached this rank after a service period of about 15 years. A captain with ten or more years of service suddenly found himself confronted with a rifle major who, during his active time, was possibly only a platoon commander or corporal , or even completely unserved. Tensions could not be avoided here. The Supreme Commander in Tyrol, Field Marshal Lieutenant Dankl , issued an order in November 1915 that insults and improper treatment of the Standschützen officers would be severely punished.

The standing rifle units were inspected for the first time in April. In the course of this inspection, the riflemen were divided into suitable for front duty (counted among the field formations) and suitable for reduced mobility (deployment in guard and replacement departments). Italy's declaration of war on Austria-Hungary was expected . For this reason, the Standschützen were mobilized on May 18, 1915 . Just one day later, the first formations in South Tyrol moved out to the southern front. Another three days later, trains coming over the Brenner Pass arrived at the new front with North Tyrolean stand contactors. Italy finally declared war on Austria-Hungary on May 23rd.

Welschtiroler Standschützen

The members of the Standschützen formations in Trentino were not entirely at ease with the Austro-Hungarian army command. Although the shooting ranges had existed for a very long time, people were suspicious of the Italian-speaking Tyroleans and tried to classify them according to their reliability. The classification ranged from completely reliable to completely unreliable . The issue of weapons and outfits to the Welschtiroler Standschützen was only given to absolutely reliable associations, although these were only used in combat operations in a few cases. Most of the time they provided guard duty or porter duty or were divided into workers' formations.

equipment

Until the end of March 1915, no item of clothing or rifle was planned for the Standschützen, let alone in stock or even assigned. After Italy's entry into the war on the side of the Entente, however, began to accelerate the formation of Standschützen formations that had begun in January. In the form of uniforms, whatever was found was initially issued. (The two companies of the Standschützen Battalion Schwaz, for example, marched out on May 23, 1915 in pike-gray parade uniforms of the hunter troop .) Mannlicher repeating rifles were initially not available or only in small numbers, the Standschützen initially received old, single-shot Werndl - Guns or use their own weapons. In May 1915, the North Tyrolean and Vorarlberg Standschützen received 16,000 model 98 rifles from German deliveries , the South Tyrolean formations were then equipped with the Mannlicher rifles. The Welschtroler associations kept the Werndl rifles, only the few formations used for combat missions were assigned the Gewehr 98. Machine guns were assigned to the individual units if necessary, but those who had good connections, such as the Bolzano Battalion, had their own machine gun department. The Standschützen did not carry guns, only the Schlanders battalion had an ancient 6 cm mountain cannon of unknown origin.

After a few initial difficulties, the Standschützen were assigned the outfit of the Imperial and Royal Mountain Troops. (The sudden efforts here were based on the fear that the uniformed combatants might be treated as rioters .) However, there were considerable deficiencies in terms of the quality of the equipment. So instead of the belt material, webbing material was already given out, there was a lack of bread bags and spades (both were improvisationally made from everything possible). As a badge, the Tyrolean units carried the Tyrolean eagle on the grass-green parolis and the Vorarlberg coat of arms . On the left side of the cap, the edelweiss of the mountain infantry could be affixed, on the front of the cap there was the specially designed badge with the motto "Hands off Tyrol". As a badge of distinction for the NCOs and men, instead of the envisaged silver-embroidered rosettes, which were difficult to obtain in this quantity (only the officers received these), the regular army celluloid stars were used.

The rescue depots of the shelters had to be used for the medical equipment , which were cleared and packed in mountain racks and assigned to the battalions. Each battalion received two medicines - and two bandages.

It was planned to equip with flags , but they were only given to the Bolzano, Kaltern, Passeier and Meran II battalions. Many of the other formations carried their rifle flags when they were sworn in and when they marched out.

March out

After the mobilization order by Emperor Franz-Joseph I on Tuesday, May 18, 1915, 39 German Tyrolean rifle battalions and two independent rifle companies, six Vorarlberg battalions, four Welschtiroler battalions and 41 Welschtiroler rifle companies formed.

Already on May 22, 1915, one day before Italy declared war, the Standschützen moved to the imperial border in the south and south-west. The only exceptions were the Zillertal and Nauders-Ried battalions, which remained to protect the main Alpine ridge , and the Lienz battalion, which was initially deployed to protect the East Tyrolean border south of the Drautal and remained there until September 1915.

Distinction badge of the Standschützen (examples)

Areas of application and uses

The operational area of the Standschützen extended over all five defensive paleons of the South Tyrolean front. It ranged from the three-language peak on the Swiss border to the eastern foothills of the Carnic Alps on the Kreuzbergsattel.

Although the Standschützen were used almost exclusively to repel the frequent Italian attacks, they also took part in the offensives (even if only in the second wave). In addition to trench warfare, they also carried out patrols and reconnaissance operations. Their other main task was labor, they built positions, accommodations, caverns, barbed wire obstacles and helped repair the damaged fortifications . In addition, the standing riflemen were used for porter services for the replenishment, as disabled people (patient carriers, today medical soldiers) and in the security service.

In the first few weeks the Standschützen were on their own to defend the Tyrolean Front. In spite of everything, these weak troops were able to stop the Italian attacks, as the Italian leadership could not believe that the border was virtually unprotected. Only later did regular troops and soldiers of the German Alpine Corps as well as Kaiserschützen and Kaiserjäger arrive . Unlike many other officers, they recognized the Standschützen as full-fledged soldiers. The Austrian war strategists initially described the Standschützen as a disordered bunch without any war experience . But thanks to their courage, their high accuracy and their mountaineering skills, the Standschützen gained respect and esteem.

Summary

It cannot be doubted that the use of the Standschützen in May 1915 saved Austria-Hungary at this point in time. Only 12,000 rifles were available in active troops, which theoretically meant that a man could only be provided with a rifle every 30 meters. Thus the 23,000 standing riflemen under arms formed the backbone of the defenses with 2/3 of the total available strength. The German Alpine Corps was initially only able to intervene to a limited extent, as Germany was not yet at war with Italy at the time and German troops were not allowed to enter Italian soil.

Due to the excellent local knowledge of the riflemen, they were often able to forestall Italian patrols and reconnaissance operations and to repel them. In particular, since the correct uniforms were in place in the meantime, the impression was given that these were regular workers, which may have influenced the hesitation of the Italian leadership. The moral value of the Standschützen also lay in the fact that his property and his family, which had to be protected, were often not far behind the front. The purely military value of the Standschützen formations varied widely. The proverbial stubbornness and stubbornness, especially of the mountain farmers, often led to a lack of discipline and arbitrariness. On June 12, 1915, Field Marshal Lieutenant Goiginger reported to Innsbruck that Standschützen “went out of action on their own initiative” at Monte Piano. Such incidents, however, were by no means the rule and remained isolated cases. In order to strengthen military discipline, active master officers were now also assigned as commanders to the riflemen. Furthermore, after the personnel situation had relaxed somewhat due to the arrival of troops from the Eastern Front, the Standschützen began to be trained more militarily. Men and officers were assigned to various training courses to learn the latest tactics and techniques. At the suggestion of the German Alpine Corps, active troop units were pushed into the sections of the front that had hitherto been held only by the standschützen. So a kind of corset was formed and the fighting strength was further strengthened.

The situation with the Welschtiroler Standschützen was a little different. It may be that it was due to the undisguised mistrust and aversion of the leadership, or that other circumstances were responsible, desertions occurred here, even if they were not the order of the day were. This was often due to the fact that at the beginning of the war the front had been withdrawn in some places for strategic reasons and terrain had been given up (e.g. the Cortina basin ). As a result, some of the Standschützen's home villages suddenly found themselves behind the front in hostile territory, which also made contact with family members by post as good as impossible, since there had been no postal connections between Austria-Hungary and Italy since the beginning of the war. On October 25, 1916, two men from the Standschützenkompanie Tione (today Tione di Trento), which was in Judiciary , because their hometowns were on the other side of the front in the Italian-occupied area, deserted . The officer in charge , who did not prevent the escape, was brought before a military tribunal and shot dead .

The 52nd Half-Brigade in Valsugana reported on June 1, 1915 that unreliable Italian-speaking riflemen had been disarmed and used as workers. Regardless of this, at least at the beginning of the war, some Welschtiroler Standschützen formations fought doggedly against the intruders, such as the companies Ala and Borgo, who received a special commendation (commendation) for this. Nonetheless, the Welschtiroler associations were gradually all disarmed and at the end of the war consisted only of workers' formations. However, this also applied to the Ladin units (e.g. from Cavalese) who did not want to be regarded as Italian and whether this measure was very bitter.

Final phase

Since, on the one hand, replacement of personnel in the standschützen formations could not be assigned, or only to a very limited extent, on the other hand, there were a large number of people leaving the older age groups due to stress and illness, the personnel situation deteriorated after a short time. This went so far that entire companies had to be dissolved or merged, battalions were downgraded to companies, or, as with Merano, the three existing battalions were merged into one. The mood also sank more and more the longer the war lasted, which was also due to the persistent and unstoppable insults and degradation by active officers, disadvantages in the allocation of food and replacement equipment, as well as harassing assignments. In 1918 the bread ration made from inferior corn flour was theoretically 500 grams per man per day, but this was often enough reduced to 125 grams per man per day. There was often only 160 grams of meat for the man at the front, but nothing for the others. The fat filtration was about 8 grams per day per man.

Nevertheless, the units, which had been grouped into Standschützen groups (battalions) since mid-1918, stood steadfastly at their posts, even when the Hungarian and Czech regiments began to disband. Only at the battalions in Dornbirn and Pustertal did rebellions arise in the very last days of the war when the order to reassign them came in. But even this situation could be cleared up again by the officers.

Most of the Standschützen fighting in the western and southern sectors were taken prisoner in Italy at the end of the war. After the “liberation from the Austrian yoke” ( Gabriele d'Annunzio ), the Italian-speaking Standschützen were subjected to harassment and reprisals for years, which included forced deportation to distant parts of Italy. (An example is the Standschützenkompanie Strigno , whose members were arrested and not captured after the end of the war and deported to Abruzzo.)

Commended actions by the Standschützen

- Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Schlanders: For participating in the conquest of Monte Scorluzzo

- Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Enneberg: For the defense of the Sief position ( Monte Sief )

- Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Innsbruck I: For the defense of the Zinnenplateau ( Drei Zinnen )

- Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Sillian: For recapturing the top of the forame

- Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalions Imst, Kufstein, Glurns and Greis: For participating in the South Tyrol offensive

- Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalion Merano: For participating in the autumn offensive of 1917 and the storming of the Leone armored factory in Valsugana

- Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalions Kitzbühel, Schwaz, Sterzing and Meran I: For the battles on the plateau of Lavarone / Folgaria

- Imperial and Royal Standschützen Battalions Kaltern, Meran II, Reutte II: Commendation by the commander of the XVII. Corps General of the Infantry Kritek for outstanding service

- kk Standschützenkompanie Ala: For outstanding services in defensive combat

- kk Standschützenkompanie Borgo : For outstanding services in defensive combat

tradition

The tradition of standing riflemen in the Austrian armed forces is followed by the military command in Innsbruck.

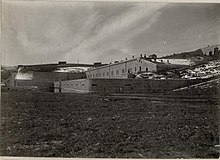

- In recognition of the services of the Standschützen in the years of the First World War and also with regard to the maintenance of tradition, the barracks in Innsbruck at Kranebitter Allee 230 were named “Standschützenkaserne”.

- The commemoration day of the Standschützen is August 13th in memory of the Battle of Bergisel in 1809

- The traditional march is the march “Under the Tyrolean Flag” by Hans Eibl

Even after the end of the war in 1918, the rifle system in South Tyrol was preserved as a traditional institution in the region, despite all the prohibitions and brutal Italianization methods of the fascist era that began soon afterwards. (Even hiding a rifle flag was severely punished - but most of the South Tyrolean rifle flags were brought to safety and are still there today.) Nonetheless, in the 1970s, the establishment of rifle companies in Trentino began again in the tradition of those that were dissolved in 1918 Standschützen Associations. An example is the rifle company of Castello Tesino in Trentino. July 2009 was reorganized.

Others

During the time of the National Socialist occupation of South Tyrol, the Gauleiter of Tyrol-Vorarlberg Franz Hofer incorporated the Standschützen into the Volkssturm in October 1944 . A formal renaming was rejected by Adolf Hitler in 1945 , but the Volkssturm battalions were called Standschützenbataillone and had a diamond- shaped sleeve symbol with a Tyrolean eagle on the swastika and the inscription "Standschützen Bataillon (place)".

In memory of the Standschützen, Sepp Tanzer composed the “Standschützenmarsch” in March 1942 and dedicated it to Gauleiter Franz Hofer.

Tables of Uses

The locations and periods of use of the various contactor units can be found here. These are not just combat missions.

Ortler section

From the Stilfser Joch , over the Ortler and Ortler Vorgipfel, the Trafoier Eiswand , the Eiskögelen, the Thurwieserspitze , the Königsspitze , the Suldenspitze to the random peaks . The riflemen used here played a key role in the attack and the taking away of Monte Scorluzzo in June 1915. Only the 1st Battalion of Infantry Regiment 29 and a few soldiers of the riding Tyrolean rifles were available here as active troops .

| I. | II. |

|---|---|

|

|

Tonale section

From the Zufallspitze over the Monte Cevedale , Monte Vioz (3645 m), the Punta San Matteo (3678 m), Corno dei Tre Signori (3359 m), Punta di Montozzo (2863 m), Punta di Albiolo (2970 m), the Tonale pass to Passo Paradiso (2573 m) in the Presanella / Adamello group. Only the 2nd Battalion of Infantry Regiment 29 and a few soldiers of the riding Tyrolean riflemen were available here as active troops.

| I. | II. |

|---|---|

|

|

Judiciary Section

Cima Presena (3046 m) - Mandron hut (2448 m) - Crozzon di Lares (3354 m) - Corno di Cavento (3402 m) - Carè Alto (3465 m) - Dosso dei Morti (2381 m) - Carriola plant - Monte Cadria (2254 m) - Monte Gaverdina (2054 m)

| I. | II. |

|---|---|

|

|

Section fortress Riva

Monte Gaverdina - Rochetta (1521 m) - defensive wall in front of Riva - Riva fortress - Lake Garda - Malga Zurez - Loppio

| I. | II. |

|---|---|

|

|

Etschtal-Rovereto section

Loppio - Manzano - Sacco - Castel Dante - Serrada plant

| I. | II. |

|---|---|

|

|

Folgaria - Lavarone section

Serrada - Coepass - interplant Sommo - Monte Durer - work Sebastiano - Luserna - Gschwent - Luserna - work Verle - items Vezzena

| I. | II. |

|---|---|

|

|

Section Valsugana

Cima de Vezzena (1908 m) - Monte Cimon (1525 m) - Tenna plant - Colle delle benne plant - Busa Grande replacement plant (1500 m) - Monte Panarotta (2002 m) - La Bassa (1834 m) - Pörtele (2152 m) - Schrimbler (2204 m) - Schwarzkofel (2301 m) - Kreuzspitz (2490 m)

| I. | II. |

|---|---|

|

|

Fiemme Valley section

Kreuzspitz - along the Lagorai ridge - Cauriol (2494 m) - Colbricon (2603 m) - Cima di Lusia - Rizzoni (2625 m) - Cima Ombert (2670 m) - Cima de Bous (2464) m - Sasso di Mezzodi (2733 m )

| I. | II. |

|---|---|

|

|

Section Pustertal

Sasso di Mezzodi (2727 m) - Pordoijoch (2242 m) - Ruaz roadblock - La Corte plant - Col di Lana - Settsass (2571 m) - Tre Sassi plant - Travenanzestal - Monte Piano - Plätzwiese plant - Toblinger knot - Innergsell (2065 m ) - Carnic ridge to the Carinthian border.

| I. | II. |

|---|---|

|

|

literature

- Benedikt Bilgeri : The national defense. In memory of the march out of the Vorarlberg Standschützen 50 years ago. Teutsch, Bregenz 1965, OBV .

- Rolando Cembran: "Baon Auer". The odyssey of the Standschützen Battalion “Auer” No. IX (1915–1918). Manfrini, Calliano (Trentino) 1993, ISBN 88-7024-483-0 .

- Renato Des Dorides: The Standschützen from the Meran Battalion in World War I , Effekt Verlag, Auer 2016 ISBN 978-88-97053-38-5 .

- Helmut Golowitsch: "And if the enemy comes into the country ..." Riflemen defend Tyrol and Carinthia. Standschützen and volunteer riflemen 1915–1918 . “Buchdienst Südtirol” Kienesberger, Nuremberg 1985, ISBN 3-923995-05-9 ( series of publications on contemporary history of Tyrol. 6, ZDB -ID 1068770-1 ).

- Oswald Gloßer, Erich Egg : Tyrolean Standschützen. Four hundred years of national defense in Tyrol. Exhibition commemorating the departure of the Tyrolean Standschützen at Pentecost 1915, June to September 1965. Tyrolean State Museum Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck 1965, OBV .

- Rudolf Huchler: The Standschützen Battalion Dornbirn in the World War . Publisher of the author, Höchst 1927. (Online at ALO ).

- Yearbook of the Kaiserschützen, Tirolean Standschützen and Tirolean Landstürmer. (Course of publication: proven 1924–1925). Wagner, Innsbruck, ZDB -ID 555983-2 .

- Wolfgang Joly: Standschützen. The Tyrolean and Vorarlberg Imperial and Royal Standschützen formations in the First World War. Organization and commitment . Universitätsverlag Wagner, Innsbruck 1998, ISBN 3-7030-0310-3 ( Schlern-Schriften. 303).

- Oswald Kaufmann (ed.): My war chronicle. With the Standschützen Battalion in Bezau in South Tyrol and Albania. World War 1, captivity, economic crisis and inflation 1914-1925. 2nd Edition. Vorarlberg Military Museum Society, Bregenz 1997, OBV .

- Karl Kelz: The Standschützen of the Feldkirch judicial district in World War 1914–1918. With an appendix of local history memories . Graff'sche Buchdruckerei, Feldkirch 1934. (Online at ALO ).

- Anton von Mörl : Standschützen defend Tyrol 1915–1918 . Universitätsverlag Wagner, Innsbruck 1958 ( Schlern-Schriften. 185, ZDB -ID 503740-2 ).

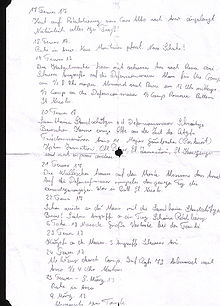

- Heinz Tiefenbrunner, Südtiroler Schützenbund, Süd-Tiroler Unterland district (publisher): Standschützen Bataillon Kaltern 1915–1918. From the war diary of Major Johann Nepomuk Baron Di Pauli. Athesia Publishing House, Bozen 1996, ISBN 88-7014-865-3 .

- Peter Tschernegg, Sigi Schwärzler: Vorarlberg's Standschützen in World War I , self-published 2014.

- Fritz Weiser (Red.), Kaiserschützenbund for Austria (Ed.): Kaiserschützen, Tiroler-Vorarlberger Landsturm and Standschützen. Göth, Vienna 1933, OBV .

- Bernhard Wurzer: Tyrol's heroic days 150 years ago. Tyrolia-Verlag, Innsbruck (among others) 1959, OBV .

Individual evidence

- ↑ The new national defense law for Tyrol including the new shooting range regulations and ordinances on the preferential treatment of standing shooters . (Online at ALO ).

- ↑ a b c d e Ludwig Wiedemayr: World War II scene in East Tyrol. The communities on the Carnic Front in the eastern Puster Valley. Nearchos, Archaeological-Military-Historical Research, Volume 2. Osttiroler Bote Medienunternehmen, Lienz 2007, ISBN 978-3-900773-80-9 .

- ↑ Entry on Kk Standschützen in the Austria Forum (in the AEIOU Austria Lexicon )

- ↑ The Standschützen . In: District Chamber of Agriculture Lienz: Osttiroler Bote . Edition of November 29, 2007, ZDB -ID 522804-9 .

- ↑ Joly: Standschützen , p. 36.

- ↑ Video on YouTube

- ↑ See the report with photos in the Bozner Tagblatt , October 21, 1944, p. 3

- ^ Franz W. Seidler: "Deutscher Volkssturm". The last contingent in 1944/45. 2nd Edition. Herbig, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-7766-1608-3 , p. 113f.

Remarks

- ↑ Standschütze is derived from the shooting range or shooting range and denotes in the general sense the member of a shooting club.

- ↑ Austrian military jargon for registered (from the old French enroller ).

- ↑ Standschützen under 17 years of age were only allowed to be used in reverse duty .

- ↑ Austrian for uniforms, uniform .

Web links

- Echon Online: War in the Alps , accessed October 25, 2015