History of Egypt

This article covers the history of Egypt from the first settlement of Egypt and its immediate surroundings to the present day.

Paleolithic

Early Paleolithic

Some representatives of Homo erectus are likely to have left Africa for the first time around 2 million years ago towards the Levant , Black Sea region and Georgia, and possibly via northwest Africa towards southern Spain. About 600,000 years ago there was probably a second wave of propagation. Then Homo erectus developed into the Neanderthal in Europe , while in Africa about 200,000 years ago Homo erectus became the archaic Homo sapiens and from this the anatomically modern man emerged. Homo erectus , which comes from East Africa, reached Israel 1.8 million years ago, similar to Georgia, but so far no traces have been found in Egypt. As early as the 19th century, however, stone tools were found in the Nile Valley that can be assigned to the late Acheuleans . Closed groups of hand axes that may be 300,000 to 400,000 years old have been found in Egypt, such as in the Nile Valley. Rescue excavations in Nubia , which before the start of construction of Lake Nasser began, showed that the region perhaps represented a culture province, as typical of Africa Cleaver were missing. These are large, rectangular artifacts, usually made on both sides, with a sharp, wide edge at one end.

The Nile Valley has been inhabited continuously for around 500,000 years. The Sahara, on the other hand, was only habitable when there was sufficient rainfall. The lower Nile was not directly affected by the cold ages, like the north of America, Europe and Asia, but in the south the glaciers absorbed water during these phases, which only flowed to the lower reaches of the river to a lesser extent. The remains of these phases are 20 to 30 m above today's flood level. Rare old Paleolithic sites and more common Middle Paleolithic sites are mostly located in these higher-lying areas. Fishing began at the latest in the Middle Paleolithic, which became tangible in Egypt 230,000 years ago.

In the oases of Kharga and Dakhila, as well as Bir Sahara East , about 350 km west of Abu Simbel , artifacts from the Old Paleolithic were found. 10 km further east, near Bir Tarfawi and in a wadi 50 km southeast of it ( Bir Safsaf ), a site that was located on an ephemeral lake, artefacts were probably found from the Middle Acheuleans on the border between Egypt and Sudan. Apparently tools were made from the stone immediately on site and no longer carried around.

Middle Paleolithic

Characteristic of the Middle Paleolithic, as in the rest of the Mediterranean, is the shield core or Levallois technique , which is associated with the Neanderthals in Europe, the Middle East and West Asia, but who did not live in North Africa. This cutting technique rationalized the use of stone as a raw material and led to the refinement of the tools made with it. In addition to the Levallois target tees, blades, points and scrapers were manufactured. In Egypt, too, in the Middle Paleolithic, the composite tools made by connecting several parts can be documented, as well as forward-looking planning already during the extraction and preparation of the stone components of the overall tool.

The epoch, known as the Nubian Middle Stone Age or Nubian Middle Paleolithic, initially shows strong similarities with the simultaneous cultures of the Mediterranean, whereas in the last phase influences of the Central and West African Sangoan - Lupemban (before 30,000 or until after 13,000 BC) are more evident .). The first phases apparently got by without hand axes, instead blade tips or knock-off tools dominated . At the same time, the raw material used was not flint, but a very hard sandstone. The finds from the Khormusan, some made using the Levallois technique, are dated between 65,000 and 55,000 years ago. Apparently the Khormusan comes from the same time as the Dabhan in Cyrenaica. But a dry phase followed in which the connecting regions between the two cultures became uninhabitable.

The hunting spectrum occasionally included hares and porcupines as well as wild cats , but also buffalo , hippopotamus and giraffes . But the most common food was the gazelle, especially the Dorcas gazelle , which occurs in all arid regions of North Africa. Excavations in the Sodmein cave near Quseir in the mountains on the Red Sea point to considerably wetter phases in which crocodiles, buffalo, elephants, kudu and other large mammals lived here. Such sites have not yet been found in the Nile Valley; instead, mining sites for raw materials such as Nazlet Khater and Taramsa (n) were discovered there.

At the same time the climate became drier. This meant that hunting animals and edible plants were almost exclusively found in the river valleys, and people in the drying areas were forced to move there. In the last section of the Middle Paleolithic, the Taramsan , a considerably drier phase, the production of a large number of mostly long blades from a single, extremely large core succeeded. In the impressive Taramsan I quarry near Qena , which gave the epoch its name, the transition to Upper Paleolithic blade manufacture can be captured . There was also an anatomically modern skeleton of a child buried there, which was dated to around 55,000 years ago.

During the migration of modern people towards the Levante ( Out of Africa 2 ) there were apparently two high points, namely 130,000 and 80,000 years ago. The two processes were separated from each other by the aforementioned drastic climate change. Occasionally, a distinction is made between Out of Africa 2a and Out of Africa 2b , whereby the first emigrants may have been defeated in the food competition with the Neanderthals (or failed for other reasons), while the second emigration succeeded.

Upper Paleolithic

Upper Paleolithic sites are rare in Egypt. The oldest site, Nazlet Khater, is on the transition edge between the desert and the Nile valley. Around 40,000 year old traces of what is probably the oldest mining flint extraction, as well as the remains of a modern person ( Nazlet Khater 2 ), which could be dated to an age of 38,000 years, were found there. In order to get to the coveted types of stone, not only 2 m deep trenches were dug here for the first time, but also the oldest underground galleries were created. These originated on an area of over 25 km² in a period of 35 to 30,000 years ago.

The deceased, who is considered to be the oldest modern person in Egypt, was a 1.65 m tall adolescent with very strong arms, who was buried under stones and sand at a depth of about 60 cm. He was found about 250 m from the nearest flint store. The body was buried on its back. Its head shape points to similarities with the oldest find of modern man in Europe, which was made at Peştera cu oasis in Romania . The sharp changes in the backbone may indicate (too) early, hard work in mining. Next to his right ear was a broad hatchet or adze like the ones used in mining.

Various methods were used to mine the flint. Trenches were dug, vertical shafts and underground galleries. The horns of hartebeest and gazelle were used as picks, as were stone axes . One of the trenches measured 9 by 2 m and was dug 1.5 m into the wadi. Vertical tunnels were dug down to the gravel ground with the flint, where they were widened to form a bell.

The next youngest archaeological industry is the Shuwikhatien, which lacks ax-like tools. Shuwikhat 1 has been dated to 25,000 BP . It was a fishing and hunting camp, several of which were found around the Upper Egyptian Qina and Esna . Blades , end scrapers and burins predominated.

In the western desert areas artifacts of the Atérien , which otherwise predominates in northwestern Africa, were found . However, the Upper Palaeolithic of Egypt seems to have been comparatively isolated, although contacts to Cyrenaica and the south of Israel and Jordan are possible.

Late Paleolithic

In contrast to the Upper Palaeolithic, quite a lot of sites are known from the late Paleolithic in Egypt. They go back between 21,000 and 12,000 years. The climate remained extremely dry, and the Nile carried less water. Heavy erosion in Ethiopia caused the mud layers in Nubia to swell to a height of 25 to 30 m above today's level. At the same time, the level of the Mediterranean sank by more than 100 m when the last major glaciations occurred in the north. These two processes have the consequence that the potential archaeological sites are inaccessible; consequently there are no finds from lower or middle Egypt. In addition, the Nile valley sank so deep that there was increased erosion on its steeper banks.

A 20 to 25-year-old man was found in Wadi Kubbaniya near Aswan who had been killed by arrows 23,000 years ago. His right arm must be broken while trying to fend off an attack. The man lived in an area that was very advantageous for hunters and gatherers, because the dunes of the Nile, which were piled up every year by its floods, blocked the outflow of the wadi, so that a lake was created here. There were several camps here that were visited seasonally. Sourgrass , chamomile, and tiger almond were part of the diet , the latter requiring careful handling, which may explain the large number of millstones found on the site. Fish, especially catfish, made up the largest proportion of animal food . Apparently both the rising tides and the shallow water of the beginning dry season in November were used to catch whole schools.

The slaughterhouse E71K12 near Esna belongs to the fakhuria. Numerous animals gathered here and moved from the floodplain to this natural groundwater lake. The main prey of the hunters were red hartebeest , aurochs or wild cattle and gazelle. The sites are likely to represent the general, strongly seasonal part of the year at the end of the Nile flooding and the time after.

The Nubian Upper Stone Age, or Neolithic Age, was followed by a final Stone Age phase known as the Nubian Final Stone Age . Its first phase is called Halfan (17,000 BG); it was followed by the Qadan (between the 2nd cataract and southern Egypt), the Arkinia and the Shamarkia .

The warming after the end of the last glacial period resulted in massive changes in the entire Nile. The floods were extraordinarily productive and reached areas that had hardly seen any water for a long time. This phase, known as the “wild Nile”, was not caused by precipitation in the still dry Lower Egypt, but by a strong climate change in sub-Saharan Africa. Makhadma 4, an affan industry site from around 12,900 to 12,300 BP north of Qena, was missed by the catastrophic flooding. Today it is 6 m above the flood level. 68% of the fish remains found there came from tilapia , 30% from predatory catfish . Apparently the fish was preserved by drying in pits. At the Makhadma 2 site, predatory catfish were apparently the basic foodstuff during the "wild Nile" phase around 12300 BP.

The microlithic qadan industry south of the 2nd cataract is primarily associated with three burial sites. There, 300 km south of Wadi Kubbaniya, was the cemetery at Gebel Sahaba (12,000 to 10,000 BC). Of the remains of 59 men, women and children unearthed there, 24 showed signs of serious injuries. Some still had arrowheads in their bodies, even in their skulls, so that a massacre can be assumed. This picture is confirmed by a kind of mass grave of up to 8 people in a pit. A smaller cemetery was found on the opposite side of the Nile. No traces of violence were found there.

The Sibilien industry can be found in the entire area between Qena and the 2nd cataract. This industry is characterized by large discounts and a preference for quartz and volcanic rock types. Since such preferences do not otherwise exist in Egypt, it could be the intrusion of groups from outside the country.

The first example of rock painting was discovered at site XXXII on the 2nd cataract. To the south of Edfu, i.e. in Egypt proper, images of fish traps were found near el-Hosh.

Between 12000 and 7000 BC BC sites in the Nile Delta are extremely rare. Apparently the area was almost completely depopulated, to which drought, but perhaps also the high mortality, contributed.

Around 6700 BC settled at the Nabta site. Shepherds with their cattle on a shallow lake barely 100 km from Wadi Kubbaniya, on the eastern edge of the Sahara. There were 12 round and oval huts there. Around 5800 BC Sheep and goats were added.

Ceramic in its oldest form in Nubia can be assigned to the Shamarkian ; this also applies to the roughly simultaneous phases of the Abkan and Khartoum . These ceramic types are strongly influenced by Egypt. The later settlements were considerably larger than those of earlier epochs, so that it is assumed that they were already villages with cultivated land.

Epipalaeolithic in the Nile Valley and in the desert

From 7000 BC BC people lived in the Nile Valley again, but only a few sites are known. Hunting, fishing and collecting continued to provide the basis of life. Artifacts from the time between 7000 and 6700 BC were found near Elkab. In contrast to the fishermen of the previous periods, the inhabitants equipped boats. In the area of the wadis, aurochs , dorkas and mane sheep were hunted . The Elkabian industry was microlithic, millstones existed, but red pigments were found on many of them, so that they cannot be taken as evidence of agriculture. The inhabitants were more likely nomads who moved to the desert in the rainier summer and hunted and fished in the Nile valley in winter. The Qarunia was formerly called Fayyum B. Its sites are found above around 7050 BC. Proto-Moeris-See created in BC. The abundant fish stocks made it possible for the inhabitants to live mainly from these catches. A woman around 40 was placed on her left side in a slightly crouched position. Her head faced east, facing south. Physiologically, it appears more modern than the late Neolithic Mechtoids (Mechta-Afalou), which were related to the Ibéromaurusia .

Traces of settlement in the area of the Red Sea, more precisely in its mountainous zone, such as in the Sodmein Cave near Quseir , show the introduction of domesticated sheep and goats for the first half of the 6th millennium.

Neolithic (from 8800 BC)

Western desert: Neolithic without tillage

In the western desert, abandoned towards the end of the Middle Paleolithic, rose around 9300 BC. The rainfall increased slightly so that people could gain a foothold again for some time. They probably came from the Nubian part of the Nile Valley, and they exhibited an essential feature of the Neolithic , namely livestock farming. Thus the beginning Neolithic Egypt differs fundamentally from that of neighboring Israel, where it was connected with the tillage, as well as elsewhere in the Fertile Crescent. In addition, ceramics were found in the western desert, the Neolithic of which was probably created on site .

A distinction is made between an early (8800-6800 BC) and a middle (6500–6100 BC) and a late Neolithic (5100-4700 BC). The times between these phases were caused by the return of the drought that made the area uninhabitable. The most important sites for the early phase are Nabta-Playa and Bir Kiselba. The smaller sites were mostly hunters and gatherers' camps in salt plains , so-called playas. These were used for a long time, but had to be cleared during the annual floods. By 7500 BC BC these cattle farmers only came into the desert with the summer rains. Although we find it in every place millstones, but the related plants, such as wild grasses, wild sorghum and Watkins , a buckthorn plant , found only at archaeological site E-75-6 (7000 v. Chr.) At Nabta Playa. Ceramics were rare, and ostrich eggs were preferred for water transport . Pottery, the decoration of which refers to the symbolic level, is probably an independent invention of Africa.

Settlement reached its peak during the following two phases. Most of the numerous camps from this period are small, but some were considerably expanded. Structures like mud-covered huts, pit houses and wells now appear more frequently. The large settlements on the Playa lakes were probably now permanently inhabited. Mussels show that there was contact with both the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. Around 5600 BC Sheep and goat appear as new pets, but the majority of the meat still came from wild animals.

The tool industry changed drastically in the Middle Neolithic. The previous blade production declined in favor of tee-offs for blade-like arrowheads that were concave at the base. The pottery remains similar to that of the early Neolithic and belongs to before 5100 BC. The Sahara-Sudanese or Khartoum tradition. Shortly before 4900 BC It was replaced quite abruptly by fired and smoothed goods. A monumental complex was found in Nabta-Playa. This consisted of ten stones of 2 x 3 m, a circle of upright plates with a diameter of almost 4 m. There were also two tumuli covered with plates, and in one of the two graves the remains of a bull with long horns were found in a chamber.

Around 5400 BC The diet largely depended on herds of cattle. These herds, which consisted mainly of goats, originally came from the Levant. After 4900 BC The amount of rain decreased again, even more after 4400 BC. However, some areas remained inhabited until historical times.

Nile valley: agriculture (from 5450 BC)

For the period between 7000 and 5400 BC Practically every knowledge is missing. A small site was found in the necropolis of Thebes, in at-Tarif , another near Armant . This epipalaeolithic, ceramic culture remains hardly tangible. The pottery finds consist only of small fragments, and there are no traces of livestock or agriculture.

Between 5450 and 4400 BC The Fayyum culture (formerly Fayyum A) existed. Their tools are closely related to the culture of the western desert. There were storage pits for grain. For the first time in Egypt, agriculture is the basis of nutrition. 109 silos with diameters between 30 and 150 cm were found in one storage area. In terms of cattle, there are still sheep and goats as well as cattle, but also pigs; fishing remained significant. In addition to mussels from the Mediterranean and Red Sea, Nubian diorite and pearls made from green feldspar were found , but no copper.

Merimde culture (mid-sixth millennium to around 4000 BC)

The Merimde culture was a culture whose name is derived from the location Merimde Beni Salama, about 45 km northwest of Cairo . A distinction must be made between three chronologically consecutive settlement complexes, which differ in their material culture, burial method and settlement image. The original settlement, which can be classified in the beginning of the ceramic Neolithic, has Southwest Asian roots. Prior to and related to the Merimde culture, it is a pre-ceramic Neolithic from the Heluan site , a place 25 km southeast of Cairo.

The ceramics of the Ursiedlung mostly consist of simple plate, bowl and kump shapes. It is noticeable that its basic substance was produced without any weight additives. A herringbone pattern was usually attached to closed forms as the only ornament. Special features are vessels for cultic use (cylindrical basins with pronounced standing rings, "altars"), miniature and handle vessels.

The manufacture of stone tools is characterized by a blade cutting technique, which is more likely to be derived from epipalaeolithic industries. Drills made from chips with a tip are typical. Coarse tools are very numerous, the most common among them being scrapers that are worked on one side. Bullet tips and an arrowhead with a handle and side notches indicate the usual reinforcement here.

Small finds include a human-shaped idol, bull sculptures, jewelry in the form of processed freshwater mussels and pendants made of mollusks, ostrich egg pearls, bone artifacts with fine eyelets, a pierced cattle tooth, cut artifacts made of hard stone, red chalk for body painting, and grinding and grinding stones.

After the first settlement was abandoned, it took some time before the place was repopulated. But apart from in the cultic area (bull sculptures) there are only a few continuities that indicate a connection between the middle Merimde culture (5500-4500 BC) and the original settlement. The differences to the original settlement in ceramics are serious. On the one hand, the ceramic is leaned out of chaff; their stability benefited from this, so that much larger vessels could be made. Oval vessels were added as special forms, which became the leading form of the middle settlement layer. In addition to the red polished ceramics, there was a gray polished category, which, with the smoothed ware, completes the ceramic inventory. In contrast to the original settlement, the pottery was undecorated, and there are no cult vessels.

A break with the middle Merimde culture can be seen in the manufacture of stone tools. This manifests itself in the production of beaten artifacts from cores. For armoring weapons, arrowheads with very long wings, triangular points with a flat scarf notch and polished spearheads in the form of cross-cutters were made. Sickle inserts indicate harvesting equipment. Very long and narrow drills are typical.

There were bull sculptures and ostrich egg pearls again, but now pearls of various shapes, small clay spheroids and fishhooks made of mussel shells were added. Numerous devices made of bones came into use. Pendants made of dog teeth and bangles made of ivory served as jewelry . Small finds made of stone are also quite numerous: stone vessels made of alabaster , club heads, net countersinks as well as grinding and grinding stones. Red chalk was used by people for jewelry purposes.

In contrast to the finds of the first three layers, which indicate small settlements close to the river, the fourth and fifth layers of settlement of the younger Merimde culture (4600-4100 BC) show larger dimensions. The most obvious changes are found in the ceramic finds of the younger compared to those of the middle Merimde culture. From layer III on, the red and gray polished goods are joined by a black polished product. What is new is that the polishes form different patterns on the respective vessel. Pottery painted in impasto can also be found occasionally. Apparently there were attempts to differentiate between a smoothed utility ceramic and a polished fine ceramic that was open to innovations.

The quality standard of the stone goods is occasionally very high. Stone tools were also made from cores, only a few tools were made from blades, such as small denticulated saws. In Layer IV, the bullet tips developed into the classic Merimde tip with short beveled wings. These arrowheads then also appeared in the Fayum-A culture . Different forms of sickles appeared, they became larger.

Human and animal-like clay figurines are documented in layers IV and V. Imprint-decorated bracelets are new. The bone artifacts form the largest group of small finds.

The people supplemented their diet with hunting and fishing. From the beginning, the proportion of cattle dominated and even increased in the younger settlements. Pigs were present in all phases of settlement, the number of sheep decreased steadily from the beginning of settlement. From the middle settlement onwards, fishing became very important and contributed to nutrition at a high level up to the younger settlements. Together with the hunt for hippos, crocodiles and turtles and the consumption of river mussels, fishing indicated that the population was oriented towards the Nile. The hunt for wild game in the desert, on the other hand, was insignificant;

The grain stocks apparently belonged to individual houses, so that the economic unit of the family gained greater independence. These houses were between 1.5 and 3 m wide, their floors were sunk about 40 cm into the ground; the roofs were covered with branches and thatch. A small number of figurines have been discovered, a roughly cylindrical head of which is believed to be the oldest human representation in Egypt.

Southwest Asia no longer plays a role, but Northeast Africa. This can be seen in harpoons, dechs, clam hooks and hatchets. This cultural change is associated with an arid phase in Palestine between the middle of the sixth and the middle of the fifth millennium BC. BC, from which no settlements can be proven for the area south of Lebanon.

The younger Merimde settlements, on the other hand, have a completely different cultural profile. They have now developed into a Neolithic culture in Lower Egypt, which influenced the Fayum-A culture and the delta cultures such as the Buto-Maadi culture. Egypt took over in the third millennium BC Not the processing of tin and copper to bronze, apart from two artifacts. These are two vessels from Abydos and unclear metal fragments from Tell el-Fara'in in the Nile Delta.

Predynastics

As Prädynastik (Vordynastik) in which it is Egyptology the phase prior to the formation of dynasties in the late 4th millennium BC. Chr., Whereby the first unification of the empire was the focus. In the age of nationalism, this unquestionably represented a turning point in an era; therefore, the times of rule not borne by Egyptians, i.e. foreign rule or phases of fragmentation, are only perceived as "interim times". The predynastic includes the epochs of the Badari culture up to the beginning of the 1st dynasty .

Badari culture (5000/4400 to 4000 BC), copper processing

The Badari culture is the oldest known from Upper Egypt with a sedentary, soil-cultivating way of life. It is dated to around 4400 to 4000 BC. BC - perhaps it began as early as 5000 BC. A - and followed the Merimde culture . A previous Tasa culture (4300-4000 BC) is discussed. This culture had ceramic connections in Sudan, but animal husbandry and type of agriculture point to Palestine. It may have been a nomadic culture that interacted with the Badari culture. The Badari culture, for its part, may also have been shaped by seasonal migrations. A total of about 600 graves and 40 settlements were found.

The name Badari culture comes from the village of the same name, el-Badari, south of Asyut on the east bank of the Nile. There were small villages on the flat desert strip on the edge of the Nile. The people living there practiced agriculture, cattle breeding, hunting and fishing. There is the first evidence of copper and faience working and relations with Palestine. The shells of the Badari culture come from the Red Sea. There were round houses, probably for the cattle that were slaughtered during the periods of flooding. Wheat, rye, lentils and root crops were stored in storage pits. In addition to the core area, Badari artifacts were also found in the south at Mahgar Dendera, Armant, Elkab and Hierakonpolis , and in the east as far as Wadi Hammamet.

At the edge of their villages they buried their dead in oval pits, mostly on the left, in a crouched position and facing west, as was customary in the subsequent epochs. The graves were very unevenly distributed, with the richer graves being concentrated in certain areas of the cemeteries.

Very young children were buried within those parts of the settlements that were no longer in use. Figurines with gazelle or hippopotamus heads were used as symbolic additions. Such symbols from the animal world shaped the entire ancient Egyptian culture.

While people used rather coarse ceramic vessels in everyday life, they gave their dead fine ceramic dishes made of red or brown polished clay. Typical of the ceramics of Badariculture was the black edge strip, which was produced using a special firing technique. Another characteristic is a ribbed surface that people created by “combing” the polish on the finest vessels. Particularly thin-walled vessels characterize a certain luxury production. Among the additions there are also carvings made of ivory and bone of particular beauty. Copper can also be found sporadically in the form of needles and pearls, but in very small quantities. This distinctive grave cult can be found for the first time in Egyptian culture and shaped the following epochs.

Combs and jewelry, such as bracelets, pearls made of bone and ivory, but above all greywacke palettes, were found quite often. The latter became typical of the subsequent Naqada culture. Only a few abstract to realistic statuettes of women were found; they are made of clay and ivory.

Naqada culture (4000–3200 BC)

The Naqada culture following the Badari culture is considered to be the forerunner of the ancient Egyptian empire. It is divided into three stages, with the first stage going up to around 3500 BC. The second to 3200 and the third to about 3000 BC. Chr.

In the 4th millennium, a predominantly manufacturing economy can be documented for the first time. It is unclear whether the ancestors of the domesticated cattle, pigs and goats came from the Middle East or North Africa. Sites like Naqada provide traces of agriculture and livestock farming. The spatial extent of the Naqada-I sites extends from Matmar in the north to Kubaniya and Khor Bahan in the south. In stage II it extends northward to the eastern edge of the delta and southward to the Nubian neighbors.

Only a few traces of settlement from Naqada I have survived, mostly post holes and accumulations of organic substances. The houses were made of tamped clay, wood, grass and palm leaves. In Hierakonpolis, archaeologists excavated a hearth and a rectangular house measuring 4 by 3.5 meters.

The burial places grew in level I in relation to the previous cultures. The dead were buried in wooden or earthen coffins, and the graves were richer. The largest grave in Hierakonpolis measured 2.5 by 1.8 m. Disc clubs attest to the prominent position of some of the dead; society evidently became more hierarchical. Boats are one of the leitmotifs of Naqada II. Figurines are common, they represent either the hunt or the victorious warrior. The hunt took place with a bow and arrow, often with dogs. Of the thousands of known graves, only a few contained figurines, mostly only one. The highest number of figurines in a single grave was 16. Soon the triangular beard and a kind of Phrygian headgear became very distinctive and also had an impact far into historical times.

Naqada II has larger and more elaborate graves. At the same time, the spectrum broadened, which now ranged from small oval pits to rectangular pits with separate compartments for grave goods. Some of the corpses have already been wrapped in linen strips. In Adaima near Hierakonpolis a double grave was found with the first traces of mummification. The corpses were also occasionally dismantled so that rows of skulls were created. In Adaima, there were signs of human sacrifice (traces of cut throats with subsequent decapitation).

On 3320 BC Finds dated to the U of Umm el-Qaab near Abydos (grave U - j ) in the BC cemetery may indicate that the script was developed independently of the Sumerian script .

The term "zeroth dynasty" describes the period in which the first inscribed minor kings can be proven. These rulers first used the Serech as a name seal. Upper Egypt occupied lower Egyptian regions, which resulted in an empire unification. The red crown of the north , which later symbolically represented Lower Egypt, still stood for the northern part of Upper Egypt in predynastic times, while the white crown was mainly worn by kings in southern Upper Egypt.

In the time of Scorpio II , Ka and other rulers, cultural innovations also become clear. Soil management and trade became more complex. Scorpio diversified offices and hierarchies; Provinces and principalities merged and expanded.

Vessels with typical Upper Egyptian decorations were found in the Nile Delta and vice versa. The permanent exchange between the kingships, which was not only economically but also ideologically motivated, led to a certain standardization of material cultures. At the latest under King Narmer , it becomes clear in the vessel inscriptions and in the finds in Abyden and Thinitic tombs how multi-layered and complex the hierarchical class system has been since the Naqada culture. Given the fact that every kingdom in Scorpio's time had its own central administrative and power center, it seems to have been only a matter of leadership which of the early dynastic rulers finally succeeded in unifying the empire.

One of the greatest economic and power factors will have been the irrigation systems, the development and use of which reached their first peak under Scorpio II. However, the areas with controlled irrigation were apparently limited to very small areas.

Naqada II shows enormous advances in stone processing technology and extraction. Alabaster and marble, basalt and gneiss, diorite and gabbro were quarried along the Nile, but especially in the Wadi Hammamet. Copper was no longer only used on small objects, but increasingly replaced stone works. This is how axes, blades, bracelets and rings were made from the material. Gold and silver were also increasingly used.

For the first time, real settlement centers emerged with Naqada II, while the Nile became a long chain of village-like settlements. The most important centers were in Upper Egypt. These were Naqada, then Hierakonpolis, finally Abydos, where the first pharaohs had their necropolis built. In the southern city of Naqada, a building structure measuring 50 by 30 m was found, which may have represented a temple or a residence.

Maadi culture in the north

In the time before the expansion of the Naqada culture, there were independent cultures in the north that go back to Neolithic roots. The Cairo district of Maadi is the namesake of a culture that was tangible from the second half of Naqada I and existed up to Naqada IIc / d. Maadi goes back to the Neolithic cultures of Fayyum and Merimda Beni Salama. The culture differs in that hardly any cemeteries are known here, while our knowledge, in contrast to Naqada, goes back to settlement finds.

In Maadi, the predynastic remains cover an area of 18 hectares. Three types of settlement can be distinguished, one of which is strongly reminiscent of settlements such as Be'er Scheva in southern Palestine. The houses include oval buildings three by five meters that are buried up to three meters deep. A single house has stone walls and adobe bricks. The other house types of Maadi can also be found in the rest of Egypt. These include oval huts with external ovens and storage pits, but also rectangular huts with walls made of plant material.

The oldest ceramic pieces point to Upper Egyptian and Sudanese contacts. Trade contacts with Palestine already existed at this time. So oil, wine and raisins came from there. Flint tools also show a strong Middle Eastern influence (Canaanite blades). Combs and objects made of polished bone and ivory, such as needles and harpoons, came from Upper Egypt. Metal objects were much more common than in the south. Significant amounts of copper were found in Maadi, probably from copper sites in Wadi Arabah in the southeast of the Sinai Peninsula.

Despite these significant influences, Maadi culture was based on livestock farming and land cultivation. Pigs, cattle, goats and sheep made up the bulk of animal foods. Donkeys, which can be detected for the first time in Egypt, were used as transport animals.

Judging by the roughly 600 graves - in the south there were around 15,000 - the social hierarchy was not very well developed. Usually the dead were given one or two clay pots on the way, often nothing. However, some graves were more elaborately equipped than the others. The dead were buried in a crouched position, hands in front of their faces. The more elaborately equipped graves, albeit still simple compared to the south, were mixed with dog and gazelle graves. The Buto site shows the transition to the Naqada culture. In the beginning, Naqada pottery increased significantly and a cultural assimilation process is emerging. The social complexity in the trading empire also increased.

Old Egypt

Naqada III (3200-3000 BC) and Early Dynastic Period (3100-2686 BC)

Two factors favored a cultural, perhaps also an ethnic expansion from south to north. For one thing, Naqada was evidently much more active in trade than the north was. The central means of trade were boats and ships, the builders of which in turn relied on cedar wood from Lebanon. At the same time, it was a constant challenge to control and secure the trade routes. In any case, the independent cultural development of the north ended with Naqada III at the latest. But Naqada itself soon no longer played a role, but was overtaken by Abydos.

The trade routes to Palestine were apparently already secured at this time. There were Egyptians working with local materials in Egyptian technique. They apparently maintained a network of settlements. The trade in lapis lazuli , which came from Afghanistan , covered many more areas during this period .

In later Egyptian sources, King Menes appears (around 3000 BC) as the first king of an entire Egyptian state. He is also the first ruler of the 1st Dynasty. It is difficult for modern research to equate this king with contemporary rulers. The following first two dynasties are known as the Thinite Age . At the beginning of the first dynasty, the country's capital was moved to Memphis . The kings are buried in monumental tombs in Abydos . Large court cemeteries were built near Memphis. Campaigns to Nubia and Palestine are known of inscriptions, but apparently these were mostly just individual raids. Under the long rule of Den , Egypt experienced the height of the 1st dynasty. The font is further developed. There are advances in architecture and art. The names of institutions and dignitaries are also known from the inscriptions, suggesting a sophisticated administration. In our sources, the first dynasty is politically relatively stable. Eight rulers ruled for a period of over 100 years. In the 2nd dynasty, the center of the country shifted further and further north. The first rulers of the dynasty were now buried in monumental tombs near Memphis. In the middle of the dynasty there are some indications of the presence of confusion. The country's unity may even have broken apart. Only Chasechemui , the last ruler of the dynasty, restored the unity of the country. Two statues of him have also survived, which show all the characteristics of ancient Egyptian sculpture in terms of style and design.

Old Kingdom (approx. 2686–2160 BC)

The Old Kingdom began with the third dynasty. It is the epoch in which the typical Egyptian expression in art , religion and culture was found and, above all, developed to full bloom for the first time. The administrative center and royal residence was Memphis throughout the Old Kingdom. Most of the rulers of this era are just names for us, known for their pyramids. Texts that convey political events are extremely rare. The sun cult of Re, which was connected with an increasing importance of the king, experienced a comprehensive boom. Occasional campaigns to Palestine, against Libyans and to Nubia took place, trade contacts there remained.

Third and fourth dynasties: early pyramids, division into Gaue, increased cult of the dead

Djoser was the first important ruler of this dynasty. He was the son of Nimaathapi , who in turn was the wife of Chasechemui, the last ruler of the 2nd dynasty. Djoser had a stone pyramid built for himself. It is the first building made of carved stone in Egypt and ushers in the age of the pyramids. Its builder Imhotep was worshiped as a deity in Hellenistic times. Little is known about Djoser's reign and his successors seem to have only ruled briefly, so that the dynasty appears problematic in many ways.

Sneferu (around 2670 to 2620 BC) was the first ruler of the 4th Dynasty. He built three pyramids at once and can therefore be described as the greatest master builder in Egypt. During this time, the country was under a strong centralized regime. Much of Egypt's resources were brought to the residential region for the construction of the pyramids. The basic structure of the administration was expanded in the way that it was to remain in the entire Old Kingdom, with the highest officials often being family members of the royal family. Nubian campaigns by Sneferu are known from annals, but little else is known about his reign. His successor Chufu (Cheops) is the builder of the largest pyramid in Egypt. Only a few events are known from his reign. The same goes for Chephren , who built a pyramid almost as large. The tombs of his successors, on the other hand, are relatively small, although still gigantic in themselves.

Fifth and sixth dynasties: increased cult of rulers, rising nobility, bureaucracy

The 5th Dynasty is marked by the special attention that many rulers paid to the sun god Re . Many kings of this dynasty built monumental sun shrines while their pyramids are slightly smaller than those of the 4th Dynasty. From the end of the 5th Dynasty, the influence of the provinces began to grow. Important provincial tombs date from this period, indicating that some of the land's resources remained on site and were not brought into the residence. At the end of the 5th Dynasty, no further sun shrines were built.

In the 6th dynasty the tendencies of the 5th dynasty continued. The provinces are becoming more and more important. Residence officials are employed there, apparently to ensure control of the residence over the distant provinces. The kings now also began to build temples in the provinces, which mostly served the cult of the king. The biography of the civil servant Weni comes from the 6th dynasty , from which one learns of military trains to southern Palestine. At the end of the long reign of Pepi II (around 2245 to 2180 BC), the unity of Egypt seems to have shattered. There were various local princes who ruled practically independently of the residence, even though the ruler in Memphis was still nominally recognized as king. After the death of Pepi II, a number of little-known and only briefly reigning kings followed.

First intermediate period (2160–2055 BC), fragmentation, dominance of Thebes and Herakleopolis

After the death of Pepi II, a few previously poorly documented rulers ruled. The country fell into various more or less independent principalities, which the kings in Memphis could control less and less. The following 7th and 8th dynasties are poorly documented. According to Manetho, the 7th Dynasty is said to have consisted of 70 kings who ruled in 70 days. This dynasty probably didn't even exist. The rulers of the 8th dynasty are mainly known from later lists of kings, only a few of them have survived on contemporary monuments. The pyramid was found by King Qakare Ibi . It's small and shows the dwindling resources of the Memphis rulers. The tomb of Anchtifi comes from Upper Egypt around this time and proudly reports on his conquests there. He acted practically like an independent ruler, even if he did not run the royal statute. The 9th and 10th dynasties are described by Manetho as Herakleopolitan . Both dynasties probably ruled from Herakleopolis (in the north of the country, at the entrance to the Fayyum). Their rulers are also only known from a few inscriptions and later king lists. At around the same time, local princes assumed the royal stature in Thebes, Upper Egypt. Within 100 years they managed to conquer large parts of Upper Egypt. Fights against the Herakleopolitans are attested. Mentuhotep II , who came from Thebes, finally managed to defeat the northern enemy within his 51-year reign and bring all of Egypt under his rule.

Middle Kingdom (2055–1650 BC)

The Middle Kingdom is the second great epoch of the Egyptian Empire. It includes the 11th, 12th and parts of the 13th dynasty. The Middle Kingdom is considered to be the feudal period in Egyptian history. Local princes ruled in various provinces, although they were loyal to the king and were partially put into power by him, but left considerable land resources in the province. Compared to the Old Kingdom, there is a richly diversified wealth. The Middle Kingdom can be divided into two phases. The early Middle Kingdom up to Sesostris II. Was strongly decentralized, while in the late Middle Kingdom, from Sesostris III. the power of the local princes was severely curtailed and the administration of the country was also reorganized. A strong centralization can be observed. A new custom of the Middle Kingdom is coregentity. Many rulers put a son on the throne while they were still alive and ruled with him. Obviously, disputes over the throne were avoided in advance.

Early Middle Kingdom

After under Mentuhotep II in the 11th dynasty Egypt around 2000 BC. BC was reunited into one state, the ruler began to set up a new administration and reorganize the country. This ruler also began an aggressive foreign policy. The ruler waged war above all in Nubia , but also in Palestine. Mentuhotep II also began an extensive temple building project in which he rebuilt various local temples in Upper Egypt in stone. His son Mentuhotep III. seems to have continued his father's policy, but little is known about his reign. The 11th dynasty probably ended in turmoil. Some kings of this time are known from Lower Nubia who laid claim to the throne. At the beginning of the following 12th dynasty is Amenemhet I. He moved the capital from Thebes to Itj-taui in the region of Fayyum. Amenemhet I also succeeds in expanding the borders of Egypt into the heart of Nubia. In the east of the delta, a line of defense, the ruler's wall, was built. This ruler also starts building a pyramid again. His son and successor Sesostris I continued the policy. He mainly conquered Nubia up to the 2nd cataract and began to build fortresses there. In an extensive temple building program, almost all the important temples in Egypt seem to have been rebuilt or at least reshaped in stone. Its pyramid is in many details a copy of a pyramid from the Old Kingdom and shows how much the Middle Kingdom was oriented towards the Old Kingdom. Especially at the end of the 11th and the beginning of the 12th dynasty there were probably civil war-like conditions throughout the country. Obviously the kings were not recognized on all sides. Already at the beginning of the 12th dynasty, the Fayyum, a river oasis that had hardly been used for agriculture, was made usable for agriculture. For Amenemhet II there is evidence of campaigns to Palestine, where two cities were sacked.

Late Middle Kingdom

Under Sesostris III. began the late Middle Kingdom. The power of the local princes was now severely curtailed. The ruler waged war in Nubia, where further fortresses were built, and he waged war in Palestine, with the latter undertakings being rather poorly documented. After all, Sesostris is considered by posterity to be one of the greatest generals in Egypt. New institutions appeared in the administration. His son Amenemhet III. finally brought the fertility of the fayyum to an end. He built two pyramids, one of them near the Fayyum. His two successors only ruled for a relatively short time. With Nefrusobek , probably a daughter of Amenemhet III, the dynasty passed around 1800 BC. Chr. To the end.

The following 13th dynasty consists of a large number of rulers who only ruled briefly. The late Middle Kingdom continues uninterrupted in culture and administration, but there seem to have been disputes for the throne, of which Egyptian sources report nothing, but which can be inferred from the many kings who followed one another in quick succession. After a particularly troubled phase at the beginning of the dynasty, the rulers Neferhotep I and Sobekhotep IV , who ruled together for about 20 years, experienced a brief recovery phase, but already under the successors Jaib and Aja I , who perhaps more than 30 years Years ruled, the empire fell into disrepair. Much has been puzzled about the causes, but Asians who immigrated to the delta and at some point took power there certainly played an important role.

Second Intermediate Period (c. 1685–1532 or 1528 BC)

With the Second Intermediate Period , another epoch begins, which is marked by the incursion of Semitic peoples from the east. The Hyksos (15th Dynasty) occupied the Nile Delta and large parts of Lower Egypt and made Auaris their capital. The Egyptian court withdrew to Thebes in Upper Egypt. These are the 16th and 17th dynasties, with some research looking into the 16th dynasty as vassal kings of the Hyksos. There kings ruled in succession to the 13th dynasty. The few sources report constant wars against the northern neighbors and one learns that at an uncertain point in time Nubians invaded Egypt. The few monuments from this era show a drastic decline in art. King Ahmose at the end of the 17th dynasty is also considered to be the founder of the 18th dynasty and united all of Egypt under his rule.

New Kingdom (1550/1528 to 1070 BC)

The New Kingdom includes the 18th, 19th and 20th dynasties. Thebes became the religious and Memphis the administrative capital. The period is well documented by royal and private inscriptions, though there are many unanswered questions. The country opened up to other Middle Eastern cultures more than ever before, and the kings conducted extensive correspondence with all of the major contemporary rulers.

18th dynasty: extreme expansion, internal religious conflict

Ahmose and Amenophis I (around 1525 to 1504 BC) consolidated the now reunited empire. Thutmose I was already able to expand the border in the south of the country, as a result of which more prisoners were transferred to Egypt due to military campaigns. Nubia was conquered by the 4th cataract. The ruler also fought wars in the Middle East and reached Syria and the Euphrates . After the death of the reigning queen Hatshepsut , Thutmose III followed. ; his 33 campaigns further consolidated Egypt's supremacy, especially in the Middle East. The local small and city states up to the Euphrates became vassals of Egypt. There were conflicts with the great power Mitanni in what is now Syria.

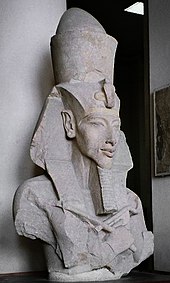

Amenophis IV moved his seat of government to the newly built city of Akhet-Aton in Middle Egypt and changed his name to Akhenaten . Above all, however, he preached the cult of the sun god Aton and pursued the cult of the god Amun and other deities. His reign plunged Egypt into a deep religious and political crisis. Shortly after his death, the successors returned to the old cults. As a result, power passed into the hands of the Haremhab military .

19th and 20th Dynasty: Wars with Hittites and Sea Peoples

Since many rulers of these dynasties bore the name of Ramses, this epoch is also known as the Ramesside period. Haremhab was followed by the 19th dynasty with Ramses I and Sethos I , who resumed the policy of conquest in the Orient, and finally Ramses II , who used all his strength to defeat the Hittites , but no real decision was made. He moved his capital to Piramesse in the eastern delta. In his 21st year in office, there was a peace treaty between the two powers. Ramses II married a daughter of the Hittite great king to confirm the good relations between the two great powers. Ramses II ruled for over 60 years, and for the second half of his reign there are signs that Libyans invaded the delta. Under Merenptah there was a counterattack that was celebrated as a victory, but the clashes continued to smolder. The 19th dynasty ended in disputes for the throne, after Merenptah some rulers who ruled only briefly followed and the country was at times divided.

In the 20th dynasty, Ramses III ruled . who managed to repel the Sea Peoples . These were different peoples who, coming from the north, overran parts of the Levant and destroyed the Hittite Empire. They could only be repulsed in the Nile Delta. In the period that followed, Egypt was marked by crises and civil wars. The seat of government remained in the north of the country. The transition to the following 21st dynasty is unclear, in any case a new ruling family, who resided in Tanis but already had power, seems to have taken over after the death of the last Ramses.

Third Intermediate Period (1069–664 / 652 BC)

In the 21st Dynasty, Egypt was ruled by kings who resided in Tanis . Especially under Psusennes I , this city was expanded into a residence. The rulers of the dynasty were probably of Libyan descent, while in Upper Egypt a sideline of the royal family ruled, the members of which carried military and priestly titles and even partially assumed royal titles. The following 22nd dynasty was also Libyan. Under Scheschonq I (around 946 to 924 BC), the founder of the dynasty, Egypt again led an aggressive foreign policy. The king invaded Palestine and sacked cities without any further conquests. Important positions in the country, such as that of the high priest, were occupied by him and the following rulers by sons of kings.

However, this quickly led to a fragmentation of the country, as many of these sons tried to usurp power and assume the title of king themselves. Overall, it is difficult for research to distinguish the individual rulers of the 22nd and the following 23rd dynasty, as they often had identical names and throne names. When the Nubian king Pije (around 746 to 715/713 BC) invaded Egypt, he found the country divided into numerous small kingdoms. Pije was the founder of the 25th Dynasty. At least in part, Egypt was now ruled from Nubia.

Under Taharqa the country experienced intense royal building activity. But this ruler also had to fight with the Assyrians , whom he was able to repel several times. 671 BC BC Memphis was conquered, but the Assyrians could not hold out in Egypt and were repulsed. Tanotamun could 664 BC. To conquer the Nile Delta and until 663 BC Chr. Drive out the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal , who however subsequently persecuted Tanotamun to Thebes. Around 655 BC BC Psammetich I ended the Assyrian rule in Lower Egypt.

Late period (664–332 BC)

After the expulsion of the Assyrians, Psammetich I, a native king, came to power again (although probably also Libyan in the broadest sense). He founded the 26th Dynasty (around 664 to 525 BC), which united Egypt. This era is often referred to as the time of the strings, as Sais in the Delta was now the capital.

Even with this dynasty it was not a matter of a single ruling family in the strict sense. While the first kings of this dynasty were related, the last two belonged to a different family. A new administration was set up inside the country. The rulers waged war in the Middle East, where the Neo-Babylonian Empire had become a strong enemy.

Amasis conquered Cyprus in the first decade of his rule and formed an alliance with Cyrene, founded by Greek settlers in what is now eastern Libya, which his predecessor had fought against. In Naukratis , a Greek trading colony was established on Egyptian soil. 539 BC The New Babylonian Empire was conquered by the Achaemenid Empire in 525 BC. They were able to defeat the ruling Pharaoh. Egypt became a satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire.

The rule of the Persians lasted from 525 to 404/401 BC. And from 341 to 332 BC The capital of satrapy was Memphis, where a satrap administered the province. In the first decades of rule the Persian kings built temples in Egyptian style and had themselves represented on them as pharaohs with a royal titular in Egyptian style. There is less evidence of this for the later part of Persian rule. The canal, which was started under Necho II and connected the Nile with the Red Sea, was also built between about 510 and 497 BC. Completed. There were various Egyptian revolts; Amyrtaios was finally able, supported by Greek mercenary armies, from 404 BC. To drive the Persians out of Egypt. He is the only ruler of the 28th Dynasty. The subsequent 28th and 29th dynasties could last until 341 BC. Withstand the Persian pressure. Above all, the rulers of the 30th dynasty developed a brisk building activity. After several attacks on Egypt, which played a dangerous role for Persia in the uprisings in the empire and in the fight with the Greeks, Nectanebos II was finally taken over by the army of the Persian king Artaxerxes III. beaten. However, Persian rule only lasted until 332 BC. Chr.

Greco-Roman Period (332 BC – 395 AD)

Alexander Empire, Ptolemaic (332–30 BC)

After Alexander the great the Persian king Darius III. defeated, he went to Egypt. The Persian satrap Mazakes surrendered the rule before Memphis. A short time later, Alexander was crowned Pharaoh according to the Egyptian rite and took the name "the beloved of Re, the chosen of Amun". The port city of Alexandria was also founded according to the plans of the king and pharaoh. The Alexandrians established a cult of the founder-hero ( héros ktístes ), yes of the founder-god ( théos ktístes ). Since Alexander withdrew with his army relatively quickly, he appointed a satrap like the Persians .

Alexander, who died on June 10, 323 BC. BC in Babylon, had given his signet ring to Perdiccas before his death . Ptolemy preferred a less centralized association of the successors of Alexander. In the " Imperial Order of Babylon " in 323 the satrapies were given to the individual generals, with Ptolemy receiving Egypt. He seized Alexander's body and the burial took place in Alexandria.

Perdiccas , who tried to hold the Alexander Empire together, advanced in 321 BC. BC to Egypt, but Ptolemy was able to repel him at Memphis. The son of Antigonus I. Monophthalmos , the successor of the murdered Perdiccas, was also born near Gaza in 312 BC. Defeated in BC, Ptolemy confirmed as Egyptian satrap. After the victory of 306 over the second who tried to conquer Egypt, over Antigonus I. Monophthalmos himself, the empires of the Diadochi established themselves . Ptolemy ruled from 305 BC. As king. Other diadochi also founded kingdoms; the Ptolemies established themselves in most of the coastal areas of Asia Minor. The Greek states hoped for Egyptian help against the Macedonian superiority, which in turn allied with the Seleucids , who ruled West Asia. Three heavy defeats ended Ptolemaic naval rule. 258 BC BC it was defeated against the fleet of a Rhodian admiral, a second defeat took place against the Macedonian king and 245 BC. BC the Egyptians were defeated before Andros . In the Fifth Syrian War , Egypt lost in 195 BC. BC also its influence in Syria to the Seleucids. Only the island of Cyprus remained Ptolemaic for more than a quarter of a millennium.

The closed Ptolemaic monetary system applied not only to Egypt, but also to Cyrene and Cyprus. But the Greek opponents made the Ptolemies to create and 246 BC. BC there was a first uprising in Egypt, 217 to 197 there was a revolt of the soldiers in Lower Egypt. Alexandria has grown into an impressive metropolis. The construction of the Alexandria library and the lighthouse , which was one of the seven wonders of the world , were completed under Ptolemy II . At least a quarter of the city was occupied by palaces, the sema, the burial place where Alexander lay in a gold, later glass coffin, was one of the showpieces. The dynasty achieved a previously impossible integration with a view to the administration and the economy in the empire. The dynasty was increasingly associated with Zeus , Dionysus and Apollo . All Ptolemies belonged to a family of gods who had their own cult with extensive sacrificial rituals.

However, in addition to the external struggles, internal struggles raged among the Ptolemies' relatives through all the following generations, in which the population also interfered, especially those of the capital. The power of the Alexandrians was first broken by the legions of Caesar in 48/47 BC. There was an independent state in the Thebais between 205 and 186 under King Haronophris, who was in 197 BC. Chr. Chaonnophris followed. Perhaps this showed the political ambition of the Amun priesthood in connection with religious xenophobia.

Rome interfered more and more in the affairs. It waged wars against the Hellenistic empires, 167 BC. The kingdom of Macedonia disappeared, followed by Asia Minor (from 133 BC) and 64 BC. The annexation of the remaining empire of the Seleucids. At the same time Rome became a guarantor for the continued existence of the Ptolemaic Empire. After the Roman victory over Macedonia, Gaius Popillius Laenas went to Alexandria to deliver an ultimatum to the Seleucid king demanding the immediate withdrawal from occupied Egypt. 96 BC BC Rome acquired the Cyrenaica, 58 BC. BC Cyprus.

During the Roman civil wars , the general Gnaeus Pompeius first landed on the run from Caesar in Alexandria, but was murdered. His victorious opponent Julius Caesar intervened in the dynastic dispute to decide it in favor of Cleopatra against her brothers. Around 50 BC There was serious unrest. 50/49 BC There were riots in the Herakleopolitian Gau, but these were put down. Finally, on October 27, 50 BC. BC issued a royal order in which all grain buyers in Middle Egypt were obliged to bring their goods only to the capital, punishable by death. Around the autumn of 49 BC Cleopatra was expelled from Alexandria.

Cleopatra, now Caesar's lover, was born in the summer of 46 BC. Invited to Rome. After the assassination attempt on Caesar, she fled to Egypt. There the queen also won the heart of Mark Antony , who gave her 36 BC. The earlier Ptolemaic territories in Syria and Asia Minor. After the couple's fleets in 31 BC BC in the battle of Actium by Octavian, the later Emperor Augustus , Egypt fell to the Roman Empire the following year .

Roman Empire

Egypt as a Roman province

30 BC BC Roman troops took Alexandria, the capital of the Ptolemies. Octavian annexed the country as a new Roman province , but only once, in the year 27 BC. Visited.

Aegyptus held a special position among the Roman provinces for a long time because of its great wealth, but also because of its cultural diversity. It was subsequently the breadbasket of the empire and was directly subordinate to the emperor, who administered the province through the praefectus Aegypti . Augustus alone gave the senators and members of the imperial family permission to enter the country. Diodorus Siculus gives the population of Egypt in the 1st century with 3 million, while Flavius Josephus gives 7.5 million - without Alexandria, which had 300,000 to 500,000 inhabitants. There were 2000 to 3000 villages with perhaps 1000 to 1500 inhabitants. Slaves made up perhaps 11% of the population, of whom about two-thirds were female. In the rest of the population there was more of a male surplus. Life expectancy for girls at birth was perhaps 20 to 25 years, for boys it was certainly over 25 years. According to the research, one sixth of the marriages were between siblings, the men married later than the women.

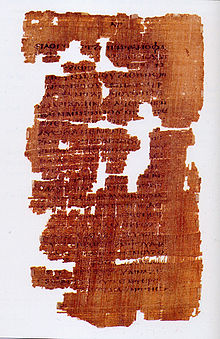

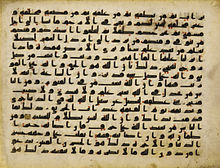

For the historical sciences, Egypt is of enormous importance, as papyri have survived better in its dry climate than in the other provinces. This is where Oxyrhynchus stands out, a place 200 km above Cairo, after which the Oxyrhynchus papyri were named. Also the ostraka , described clay tablets from the eastern desert, more precisely from the Mons Claudianus fort , of which more than 9,000 have been found, offer unusually broad and deep insights into the societies that produced them. In addition to papyri, other organic materials, such as fabrics and clothes, baskets, leather, but also food, were better preserved because of the drought.

Prefect, civil and military administration, ethnically determined hierarchy

Rome took over the administrative division of the country, so that there were still 30 nomes under the respective strategoi , who were accountable to the prefect, with their own capital. The prefect was the personal representative of his master in Egypt, military commander of the legions stationed there, appellate authority on legal issues and head of administration. For long stretches of the imperial era, the office was considered the pinnacle of a knightly career.

The first prefect in Egypt was Cornelius Gallus . Shortly after his appointment, he moved in 29 BC. BC to Upper Egypt to put down a rebellion there. Further south, he then repulsed the advancing Ethiopians.

Around AD 70, the prefecture of Egypt stepped down from the praetorian prefects in the ranking of knightly offices . The praefectus Aegypti were subordinate to three or four epistrates who also belonged to the knighthood. The administration of a province in this form was unique in the empire. The top administration was Roman, the middle administrative strata of the Gau level (Gaustrategen) Greek and only the local administration Egyptian.

The praefectus Aegypti had its seat in the port city of Alexandria. He traveled regularly through Egypt to hold court and make administrative decisions. His most important task was the tax and financial administration, in which he was supported by procurators from the knighthood. He also commanded the legions and auxiliaries stationed in Egypt . His term of office was not fixed and was determined by the respective emperor. It was usually two or three years, sometimes, as under Tiberius , it was also significantly longer.

The cities initially enjoyed no self-government. This changed under Emperor Septimius Severus in 200 when a city council was introduced in each of the thirty main towns. With that the places developed to Municipia . From 212 onwards, all cities in the empire had at least the rank of municipium, which, however, entailed considerable financial burdens. Every male resident between 14 and 60 years old had to pay an annual tax. The small group of Roman citizens was exempt from this, however, the upper classes (metropolites) paid a reduced tax.

Of the three legions, one was in Alexandria. There were also three Roman cohorts there, three more each in Syene on the southern border, and finally three in the rest of the country. The three cavalry units (alae) were also distributed throughout the country. In Alexandria the fortress Nikopolis stood, about 5 km east of the city center, there were observation towers all over the country, because any movement through the desert was only allowed with appropriate permits, be it on ostraca or on papyrus. Legionnaires also accompanied the tax collectors, guarded the grain transport on the Nile, secured mines and the transport of materials.

Uprisings, counter-emperors, administration and provinces

During the reign of Emperor Caligula , a guerrilla war broke out in Alexandria between the Hellenic and Jewish populations. In 69 Vespasian , who was proconsul of the province of Africa at the time, was proclaimed emperor in Alexandria.

Avidius Cassius , who, as a descendant of the Seleucids, made it to the praefectus Aegypti , became governor of Syria in 166. In 172 he ended the uprising of the Bucoles in Lower Egypt, which had started in 166/67 (Cass. Dio 71, 4). The leader had been a priest by the name of Isodorus. In 175 Avidius Cassius was proclaimed emperor by the Egyptian legions after a false report of the death of Mark Aurel had spread. He was murdered in Syria that same year.

In 268 Lower Egypt was occupied by the army of Queen Zenobia of Palmyra , while Upper Egypt was partly occupied by the Blemmyern , a Nubian tribe. In 270 the Roman general Tenagino Probus succeeded in reintegrating Egypt into the empire. In 279, Kaiser Probus led a successful campaign against the Blemmyes. Emperor Diocletian paid them annual fees, but this did not prevent them from further raids; Finally Diocletian was forced to give up parts of the threatened province. The border was moved back to the first cataract and secured by fortresses.

When a revolt broke out in Upper Egypt in 292 and Alexandria rose against the Romans two years later, Emperor Diocletian recaptured the country in 295. The last but also the most violent persecution of Christians took place during his reign. Maximinus Daia was the last Roman emperor recorded in Egypt (until 313).

As part of Diocletian's provincial reform, which separated civil administration from military tasks, the province of Egypt was divided up, which was later changed several times. The administrative area of the praefectus Aegypti was limited to Lower Egypt and at times the Fayyum Basin , the other areas were administered by praesides . The dux Aegypti et Thebaidos utrarumque Libyarum was solely responsible for military questions .

The Praefectus praetorio per Orientem was subordinate to the dioceses of Oriens , which included Egypt, the Levant, Cilicia and Isauria, then Pontica (northern and eastern Anatolia) and Asiana (southern and western Anatolia). In 395, however, Egypt was separated and the number of prefectures increased to five.

Under Constantine the Great (306–337) the administration was reorganized. Egypt became a diocese and divided into the six provinces of Egypt , Augustamnica , Heptanomis (later Arcadia ), Thebais , Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt . In 365 a severe earthquake hit the Nile Delta with an epicenter off Crete .

Economy, colony

Almost immediately Rome became dependent on the wheat deliveries from the fertile land on the Nile. A second important area were the mines, especially in the eastern desert area (including gold mines), where rare types of stone such as porphyry (at Mons Porphyrites from 29 AD to the 4th or 5th century), red granite near Aswan or were mined Granodiorite were mined on Mons Claudianus , which served the gigantic growing building needs in the Roman Empire, in the fall of Mons Claudianus probably only the imperial buildings in Rome. In addition, all trade with the east, i.e. in the direction of the Persian Gulf , India, Malaysia , perhaps even China, ran through Egypt with its center in Alexandria. The main port on the Red Sea was Berenike , which outstripped Myos Hormos ("shell port"), which was important in Ptolemaic times. The ships sailed south towards the Gulf of Aden in July and returned in November. The larger ships that cast off in Alexandria or Berenike may have been 60 m long and carried about 1000 tons. Along the 350 km long caravan route from Berenike to Koptos on the Nile there were water points every 20 to 30 km, with a branch leading to Edfu (Apollinopolis Magna). In particular, the increasing demand for building materials and luxury goods stimulated the economy.

The taxes were based on how high the flood of the Nile was, as Pliny reports. A level of 5.5 m caused famine, 6 m meant hunger, 6.5 m joy, 6 ¾ m confidence, 7 m enthusiasm. Under Augustus, the fleets brought 20 million modii of approx. 8.7 liters each to the Tiber as a tax . This corresponded to over a million tons, with suppliers possibly also having to finance the transport. The deliveries from the growing areas to the port of Alexandria were subjected to strict controls, sealed samples were given to the river captains who drove in the company of a soldier; this should prevent undergrinding or the partial exchange of goods for inferior replacements. Roman procurators received the grain and were responsible for storage and security. In May or June the ships went to Rome, where they were on the road for one, often two months because of the prevailing headwinds. They preferred coastal routes. It only took them two weeks to get back.

Papyri show how a farm like that of the wealthy landowner Aurelius Appianus worked in the Fayyum. The administrators came from the region, were either councilors or landowners themselves. The actual production was directed by phrontistai , who possibly worked for several goods at the same time. The real work was done by a tribe of workers who were reinforced in the harvest season. Apparently they were wage workers. Some worked on the estate for life and had free accommodation, others were freelance workers who often concluded contracts of several years and came from the surrounding villages. Appianus mainly produced export wine, as well as fodder for the cattle, grain for taxes and for employees.

This refers to the transition phase in the development from free farmer to colonate. Imperial laws, presumably on the initiative of the large landowners, created the prerequisites for transferring almost unlimited power of disposition and police power to local masters, whose growing economic units were thereby increasingly isolated from state influence. The rural population was initially forced to cultivate the land and taxes (tributum) to be paid. Until the 5th century, the people who worked the land were often tied to their land while their property belonged to their master, but after three decades in this legal status others could take their mobile property or their property into their own possession. Under Emperor Justinian I there was no longer any distinction between free and unfree colonies. Colons and unfree were now used identically to describe arable farmers who were tied to the clod and had no free property.

Since Constantine the Great, gentlemen have been allowed to chain fugitive colonies that had disappeared less than thirty years ago. Since 365 it has been forbidden for the colonists to dispose of their actual possessions, probably primarily tools. Since 371 the gentlemen were allowed to collect the taxes from the colonies themselves. Finally, in 396, the farmers lost the right to sue their master.

religion

Egyptian, Greek, Roman gods

The gods of ancient Egypt changed. Amun, who was originally the god of water and air, became the giver of life. Horus was often indistinguishable from Ra. The Greeks identified the Egyptian gods with their own, so that Horus was equated with Apollo, Thoth with Hermes, Amun with Zeus, or Hathor with Aphrodite. Serapis was supposed to give the Ptolemaic empire greater uniformity; he was derived from the Egyptian god Osirapis, but he was not depicted as an animal, but as a bearded man. He was especially venerated in Memphis and Alexandria, where 285 BC. The Serapeum of Alexandria was completed. The name arose from the names of Osiris (Sir / Sar) and Apis (Hepi). The Apis bull embodied fertility. The Serapis cult spread in many provinces of the Roman Empire, but also in Rome itself. The cult of his wife and sister Isis also spread, especially in Hispania. The Hathor Temple in Dendera, which was built between 125 BC. BC and AD 60, Roman emperors also made sacrifices, at least as statues.

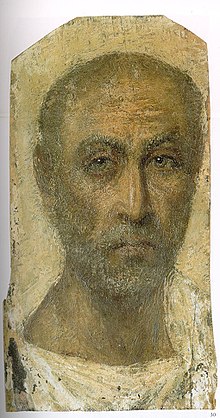

Even the Roman emperors allowed themselves to be venerated by the population as pharaohs - and even worshiped the Egyptian gods - and again called themselves Pharaohs of Egypt . In many temples there are imperial relief representations and sculptures in Egyptian costume during the execution of rituals. A mixture of Roman and ancient Egyptian elements can be observed in the cult of the dead, for example in the mummy portraits painted in Roman style . During a visit from Emperor Hadrian in 130, his youthful love Antinous drowned in the Nile. Hadrian raised him to god and founded the city of Antinoupolis in his honor , the only Roman foundation in Egypt. In everyday culture, however, forms and styles from the Hellenistic-Roman world were adopted in all areas. Material culture became largely Roman in the first century AD.

Christianization

Around the middle of the 2nd century, the first Christian groups could be found in Alexandria , at the end of the 2nd century many communities had already formed in the Nile Delta, but Emperor Septimius Severus forbade conversion to the Christian faith in 204 by edict. Under Emperor Decius (249-251) significant persecution of Christians began throughout the country, which lasted into the reign of Valerian . It was not until Emperor Gallienus that these 260 were stopped, and finally after the persecution of Diocletian. Under Julian there were violent clashes between pagans and Christians. Theodosius I made the Christian religion the state religion in 394 . Under Justinian I , pagan cult activities are still documented ( Philae ), but these were then stopped.

According to tradition, a peculiarity of Egyptian Christianity arose from Paulus von Thebes (228–341), who is considered the first hermit and anchorite through the vita of the church father Hieronymus . In contrast, Antony the Great (perhaps 251–356) became the "father of the monks". The two men not only reached a "biblical age", but also founded institutions that had a profound impact on the Mediterranean region.

With the end of the persecutions since Constantine I (313) and the increasing privileges by the state, which included tax exemption, a steeper ecclesiastical hierarchy emerged. The bishops in the respective metropolis of the provinces became archbishops from 325, to whom the other bishops of the province owed obedience. Below the Bishop plane found deacons and deaconesses , elders and lecturers , were added gravedigger, doorkeeper , Protopresbyter and subdeacons . The clergy was the only class to which all social classes had access, even if not everyone could rise to the highest positions in the most important church centers and the higher classes probably did not strive for a diocese in less respected areas. The Clergy on the estates of the landlords put residents who are tenant farmers .

Byzantine Period (395-642)

Christianity as state religion, division of the empire (395), divisions between churches

With the establishment of Constantinople as the second imperial city, Christianity gradually became the dominant religion in the Roman Empire, and in 394 it actually became the state religion. Around 400, Greek finally gained the upper hand over Latin as the administrative language in the east of the empire, but it was used in the army and at court until the 6th century.

In 391 there were clashes between pagans and Christians in Alexandria. Among other things, pagans had holed up in the Serapis shrine and forced some Christians to sacrifice or crucified. To calm the situation, Emperor Theodosius I pardoned the murderers, but ordered the destruction of the temple as a warning to the pagans of the city. In connection with this destruction, the other temples were also destroyed under the leadership of Theophilos of Alexandria . Other temples had already been destroyed by local governors and bishops. In Alexandria in 415 the pagan philosopher Hypatia was murdered by a Christian mob; but even after her there were pagan scholars in the city for decades .

But the disputes between pagans and Christians were soon overlaid by intra-Christian ones. When the empire was effectively divided in 395 , Egypt was added to the Eastern Roman Empire . At the time of Emperor Arcadius , the "founder" of the Egyptian Coptic Church Schenute von Atripe was head of the White Monastery near Sohag on the west bank of the Nile.