Austria-Hungary

The Austro-Hungarian Monarchy , in Hungarian Osztrák-Magyar Monarchia , Austria-Hungary for short , informally also k. u. k. Called the Dual Monarchy , it was a real union in the last phase of the Habsburg Empire in Central and Southeastern Europe for the period between 1867 and 1918. It existed after the reorganization of the Austrian Empire into an association of states based on the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of June 8, 1867 ( implemented constitutionally in Austria on December 21, 1867) until October 31, 1918 ( Hungary's exit from the Real Union).

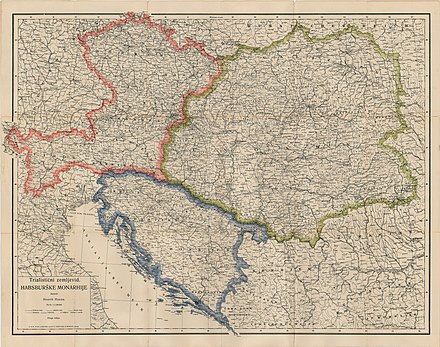

The Austro-Hungarian Monarchy was made up of two states: the kingdoms and countries represented in the Imperial Council , unofficially Cisleithanien (officially called Austria only from 1915 ), and the countries of the Holy Hungarian Crown , unofficially Transleithanien (vulgo Hungary ). Then there was the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina , which had been occupied by Austria since 1878 and which was incorporated into the monarchy as a condominium in 1908 after long negotiations. The constitutional equalization agreements ensured the equality of the two (sub) states in relation to one another in the sense of a real union . The common head of state was the Emperor of Austria and Apostolic King of Hungary from the House of Habsburg-Lorraine . Franz Joseph I ruled from 1867 to 1916 , then until 1918 his great-nephew Karl I / IV.

With around 676,000 km² Austria-Hungary was after the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908 the second largest country in terms of area (after the Russian Empire ) and with 52.8 million people (1914) the third largest country in Europe in terms of population (after the Russian and German empires ). His area last included:

- the territories of today's states

- Austria ,

- Hungary ,

- Czech Republic (with the exception of the Hultschiner Ländchen ),

- Slovakia ,

- Slovenia ,

- Croatia ,

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- as well as parts of today's

- Romania ( Transylvania , Banat , later Kreischgebiet , eastern part of Sathmar , South Marmarosh , South Bukovina ),

- Montenegro ( municipalities on the coast ),

- Poland ( Western Galicia ),

- of Ukraine ( East Galicia , Carpathian Ruthenia and Northern Bukovina)

- Italy ( Trentino-Alto Adige and parts of Friuli-Venezia Giulia ) and

- Serbia ( Vojvodina ).

The First World War , the disintegration of Old Austria at the end of October 1918 through the establishment of Czechoslovakia , the SHS State and the State of German Austria and the defection of Galicia , Hungary's exit from the Real Union on October 31, 1918, and the Treaty of Saint-Germain in 1919 and in 1920 the Treaty of Trianon led to or sealed the end of Austria-Hungary.

The subsequent republic in German-Austria ("Restösterreich") kept the Austrian name, abolished the nobility (like Czechoslovakia) and expelled the monarch and other Habsburgs who did not want to see themselves as citizens of the republic from the country. Not least because of the experiences of the following decades, there is a largely positive culture of remembrance of the Habsburg Monarchy and Austria-Hungary in today's Austria, as in some other successor states .

State name

The official state designation of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy ( Hungarian Osztrák-Magyar Monarchia ) was determined by handwriting by the Emperor and King Franz Joseph I on November 14, 1868. Alternatively, the dual monarchy also operated as the Imperial and Royal Monarchy Austria-Hungary , resulting in the informal name k. u. k. Monarchy led. Since the Danube flowed through the dual state as its main stream over a length of about 1300 km, it is also referred to as the Danube Monarchy . Because of the constitutional construction of the two parts, the term dual monarchy is also in use; this has nothing to do with the imperial double-headed eagle, which the Kingdom of Hungary did not have.

Imperial Austria was officially referred to as the kingdoms and countries represented in the Imperial Council until 1915 , but unofficially in the language of politicians and lawyers after the border river Leitha it was also called Cisleithanien . Royal Hungary was officially called the lands of the holy Hungarian crown of St. Stephen or Transleithanien . The term Austria as a comprehensive term for the Cisleithan countries was only officially introduced in 1915. In retrospect, imperial Austria was sometimes jokingly referred to in literature as Kakanien - an expression that comes from Robert Musil's novel The Man without Qualities and is derived from the abbreviation k used for the cisleithan half of the empire . k. derived.

insignia

Flags

Austria-Hungary did not have a common state flag, however

- a common red-white-red naval and naval flag (with a crowned shield), previously carried since January 1, 1787,

- Troop flags of the common army and

- a common trade flag introduced on August 1, 1869 (a combination of the naval flag and the Hungarian imperial flag, which was supplemented by the small Hungarian coat of arms).

On October 12, 1915, a series of new flags was adopted by imperial decree for the Navy, including a redesigned war and naval flag. Due to the war conditions, however, the new flags were never introduced. On the other hand, you saw the new war flag printed on postcards, for example. Some Austro-Hungarian aircraft also displayed the flag on the tail unit.

The colors of the House of Habsburg are also the flag of the kingdoms and countries represented on the Imperial Council (black and yellow). The Hungarian half of the empire had a red-white-green tricolor flag with the Hungarian coat of arms.

coat of arms

From 1867 to 1915 the double-headed eagle of the Habsburg-Lothringen dynasty ("House of Austria") was the emblem for joint (k. it was ruled by the dynasty long before the establishment of the dual monarchy and symbolized the imperial rank.

Hungarian politicians were always dissatisfied with this, because the double-headed eagle was at the same time a symbol of the Austrian, Cisleithan half of the empire. In 1915 a new common coat of arms was introduced, a combination of the coats of arms of the two halves of the empire with equal rights and the (smaller) one of the ruling house. The motto indivisibiliter ac inseparabiliter (“indivisible and inseparable”) should represent the bond between the two monarchies connected in a real union.

The (middle) coat of arms of the Austrian half of the empire showed the double-headed eagle raised by the imperial crown with a breast shield that contained the coats of arms of the crown lands . Two griffins served as shield holders . The Hungarian coat of arms was elevated by the crown of St. Stephen and flanked by two floating angels dressed in white.

The middle coat of arms of the Austrian states (redesign 1915)

development

Austro-Hungarian equalization 1848–1867

The roots of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy lie in the conflict between the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia for supremacy in the German Confederation , which was founded on June 8, 1815 with Austria as the presidential power. Austria was the main obstacle for Prussia in the small German solution , supported by the supra-regional German National Association , which provided for a merger of the states of the German Confederation under the leadership of Prussia and the simultaneous exclusion of Austria.

This dispute was decided in favor of Prussia on July 3, 1866 in the Battle of Königgrätz (“ German War ”). The most serious consequence of this war for the Austrian Empire was the isolation through the forced separation from the German states. This weakening of the Germans in Austria was offset by the strengthening of the position of the demographically dominant non-German nationalities , which raised fears that the multi-ethnic state , which had been badly shaken as early as 1848, would break up.

In order to reduce this danger, the imperial family had to relax relations with the Hungarian ruling classes. The Hungarian Revolution could only be put down in 1849 with the support of the Russian Empire . However, with the execution of the moderate former Prime Minister Lajos Batthyány and the 13 martyrs of Arad in 1850, the 20-year-old Emperor Franz Joseph I tore open a gap that had been created by the separation of Vojvodina , Croatia, Slavonia and Transylvania and the subordination of the rest of Hungary to the military administration was deepened by Archduke Albrecht .

With the liberation of the peasants , the House of Habsburg finally turned against them the Hungarian nobility as the actual decision-makers in the country. Its passive resistance in the form of denial of office and tax led to a permanent troop presence. In addition to the liberation of the peasants, the modernization of the school system , the end of patrimonial jurisdiction and the introduction of the Austrian penal code are to be noted as modernizing elements of this phase .

The confrontation was finally dampened by the economic upswing, but a substantial rapprochement did not take place until 1865 with the reconstitution of the Hungarian state parliament and the promise of extensive restitution of the Hungarian constitution of 1848 by the imperial government. Further steps were urgently needed.

The compromise negotiations with the Hungarians were dominated by reluctant Magyar opinions. The exiled spiritual leader of the Hungarian revolution, Lajos Kossuth , and his considerable following in the country voted for the separation from Austria, a compensation would (according to Kossuth) be the "death of the nation" and would "impose the pull of foreign interests" on the country .

Ultimately, however, the opinion of Liberal leader Ferenc Deák prevailed. He argued that a free Hungary, with its strong Slavic and German minorities, ran the risk of becoming isolated and ultimately being crushed between Russia and Germany. An alliance with Austria, weakened by the internal nationality problem, under the leadership of a monarch who pledges himself to the Hungarian nation in the coronation oath , would therefore be preferable. He also convinced the nobility by pointing out that the compensation would offer the opportunity to preserve the territorial and political integrity of the large estates and to continue rule over the non-Magyar nations of Hungary.

The negotiations on the settlement with the Kingdom of Hungary were concluded in early 1867. On February 17, 1867, Franz Joseph I appointed the new Hungarian government under Count Andrássy . The Vienna negotiations were concluded a day later. On February 27, 1867, the Hungarian Diet was restored. On March 15, Count Andrássy made with his government in Buda King Franz Joseph I the oath of allegiance . At the same time, the regulations of the Austro-Hungarian balance came into force. This is considered to be the birthday of the dual monarchy, even if the equalization laws passed in Hungary on June 12, 1867 were only passed in the Austrian Reichsrat on December 21, 1867 and came into force on December 22, 1867 (see December Constitution ). Franz Joseph I himself was crowned King of Hungary on June 8, 1867 in Buda .

Dual monarchy 1867–1914

Franz Joseph I was formally the common constitutional head of state ( personal union ), under whose leadership both foreign policy , the common army and the navy as well as the necessary finances in the corresponding three imperial, later k. u. k. Ministries based in Vienna were jointly administered ( Realunion ):

- k. u. k. Foreign minister; Chairman of the Joint Council of Ministers

- k. u. k. Minister of War

- Joint Minister of Finance

(The lemmas given contain lists of all office holders up to 1918.)

From now on, Austria and Hungary could regulate all other matters separately (however, a common currency, economic and customs area was voluntarily established). The conclusion of the settlement, however, by no means resolved all the issues at stake. Hungary, for example, had guaranteed an adaptation every ten years.

The negotiations on this were conducted by the Hungarians primarily with the aim of weakening the remaining ties and improving their economic position vis-à-vis Cisleithania. The negotiations between the respective commissions, which lasted for many months or even years, created a climate of permanent confrontation and strained the relationship between the two parts of the Real Union until a military operation was planned. It turned out that the influence of Franz Joseph I as Hungarian king on Hungarian domestic politics was far less than that on the governments in Cisleithania as Austrian emperor. One of his last means of exerting pressure on the Hungarians was the threat of general and free elections.

The settlement with Hungary, which had brought Hungary far-reaching state autonomy , however, led to protests from other nationalities, especially the Slavs. Concrete demands for a similar compensation were made mainly by the Czechs for the countries of the Bohemian Crown (Bohemia, Moravia , Austrian Silesia ). The disregarded interests of other nationalities and the Hungarian policy of Magyarization led to ethnic tensions and to terms such as “people dungeon”. On the other hand, the dual monarchy prospered as a common economic area with a common currency.

The non-German nationalities in Austria, where all nationalities had at least de jure equal rights, had much better conditions than the non-Magyar in Hungary, which relied on the Magyarization of the other half of the population. This mainly concerned instruction in the mother tongue (although higher non-German schools often had to be fought for), the use of the mother tongue in offices and authorities (answers in the applicant's language first had to be required by law) and representation in the Reichsrat , the parliament Austria.

However, this representation was used very differently. The Poles in the Crown Land of Galicia often worked constructively - lured by tax gifts and investments - and temporarily provided ministers or even the prime minister ( Kasimir Felix Badeni , Agenor Gołuchowski the Elder , Agenor Gołuchowski the Younger , Alfred Józef Potocki or Leon Biliński ). Many Czech politicians fundamentally denied that the Imperial Council was responsible for the countries of the Bohemian Crown, so that there had to be prescribed direct elections for members of parliament there earlier than in other crown countries . Czech Reichsrat deputies made the deliberations of the House of Representatives impossible again and again by noise orgies ( obstruction policy ) , whereupon the government proposed to the emperor that the Reichsrat be adjourned and continued to rule with provisional ordinances.

In Hungary, the non-Magyar nationalities, who made up half of the population, were discriminated against by school laws and voting rights. In contrast to Austria, where this was successful in the Reichsrat elections in 1907 , no universal and equal male suffrage was introduced in Hungary until the end of the dual monarchy . Privileges of class and property were much more decisive in Hungary than in Austria. The Hungarian ruling class worked within their political possibilities to make Hungary as completely independent as possible from Austria.

When the Berlin Congress in 1878 allowed Austria-Hungary to occupy Bosnia and Herzegovina , both formally still part of the Ottoman Empire , Austria and Hungary wanted to incorporate the new administrative area into their state. The Solomonic solution was then that Bosnia and Herzegovina was not made into Cis- or Transleithania, but was administered by the common Ministry of Finance.

After the equalization, the Emperor and King Franz Joseph I was meticulous about treating his two monarchies equally. This extended to the question of naming new ships of the k. u. k. Kriegsmarine; Franz Joseph I rejected name suggestions that would have disadvantaged Hungarians ( Magyars ). The after the suicide of Crown Prince Rudolf in 1889 and the death of his father in 1896 designated Archduke Franz Ferdinand , however, his dislike of the Hungarian ruling class and their Magyarisierungs- and blackmail policy towards the crown did not hide and planned in its military firm, he (1913 inspector general of the entire armed power ) in Belvedere Palace a reconstruction of the dual monarchy based on the army after the death of Franz Joseph I. His plan to turn the dual monarchy into a “triple monarchy” through equal participation of the southern Slavs as a third state element ( trialism ) would probably only be in a civil war could be realized with the Hungarians. In addition, the still disadvantaged Czechs would probably not have watched indifferently. On the initiative of Franz Ferdinand, models for the transformation of the monarchy into an ethnic-federal state were also designed (model of the United States of Greater Austria according to Aurel Popovici ), but they were never implemented. At the Olympic Games 1900–1912 , teams from Austria and Hungary were joined by a separate team from Bohemia . In 1905, after the parliamentary elections there , the Hungarian crisis broke out in the Kingdom of Hungary, in which the Hungarian independence party ruled without a parliamentary majority and demanded a separation of the joint Austro-Hungarian army, which in fact would have meant the end of the dual monarchy. Emperor and King Franz Joseph I called new elections in 1906 and ended the crisis.

In 1908 the Young Turkish Revolution broke out in the Ottoman Empire . Austria-Hungary was thus reminded that Bosnia and Herzegovina was affected by the k. u. k. The monarchy had been occupied and administered for thirty years, but formally remained part of the Ottoman Empire. Franz Joseph I now saw the chance to become “a multiplier of the Reich” and agreed to the annexation plan of the joint finance minister , according to which Foreign Minister Count Aehrenthal proceeded on October 5, 1908 to formally incorporate those areas. The unilateral act, not supported by any international conference, that the territory of the k. u. k. Extending the monarchy to Bosnia and Herzegovina caused the “ Bosnian Crisis ” in Europe . It became clear how few allies Austria-Hungary would have in the event of war.

In 1908 Franz Joseph I also celebrated his 60th anniversary as Emperor of Austria . On this occasion, Kaiser Wilhelm II and almost all the heads of the German states congratulated personally in Vienna. Hungary saw itself "not prompted to rallies", since Franz Joseph I had been perceived as a foreign ruler until his coronation in Hungary in 1867. In 1908 in Prague and Ljubljana there were riots against the Germans as the ruling people in the Austrian half of the empire.

The road to war - July crisis 1914

On June 28, 1914, Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie Duchess von Hohenberg visited Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia annexed in 1908 . On that day Serbia celebrated for the first time St. Vitus's Day as an official national holiday, the anniversary of the battle on the Amselfeld , on which the Serbs were defeated by the Turks in 1389 . Nationalists calling for a united Serbia (and thus areas of the monarchy where Serbs lived) found the couple's visit a provocation. While driving through Sarajevo, the couple were shot dead by the Serbian assassin Gavrilo Princip , which led to a serious national crisis, the July Crisis.

After the assassination attempt in Sarajevo , the Emperor and King Franz Joseph received a declaration of loyalty from the German Emperor Wilhelm II , who assured him that "in accordance with his alliance obligations and his old friendship [to] stand faithfully at the side of Austria-Hungary". This pledge of loyalty, which did not require that far-reaching decisions by Austria-Hungary had previously been discussed with the German Reich , was perceived by political observers as a blank check . The extent to which the German leadership was already calculating the European war at this point is controversial in historical research to this day (→ Fischer controversy ).

On July 23, Austria-Hungary issued an ultimatum to Serbia, as it was assumed that Serbia played a decisive role in the attack. The response from Belgrade was compliant and cooperative. The Serbs did not have all the conditions of the k. u. k. Dual monarchy accepted one hundred percent. Austro-Hungarian top politicians and the military therefore gladly took the opportunity to reject the Serbian answer as inadequate. In complete misunderstanding of the world situation and the weakness of the monarchy, they motivated the 84-year-old emperor and king, who had not waged a war for 48 years, to declare war on the south-eastern neighboring country on July 28th .

This moved Russia to general mobilization , as the tsarist empire saw itself as the guardian of the Slavic peoples due to Pan-Slavism and viewed the Balkans as its own area of influence. The Russian Empire declared war on Austria-Hungary. Then came the case of the alliance for the German Reich. This entered the war on the side of Austria-Hungary. Since Russia was allied with France and Great Britain ( Entente ), these two came to the aid of Tsarist Russia, with which the “Great War” - later known as the First World War - could no longer be stopped.

Austria-Hungary in the First World War

Austria-Hungary was even less prepared than Germany for a long war, especially in the economic field. Some historians even see the monarchy as the least prepared European great power. Its weak political and economic structure made it particularly vulnerable to modern all-out war, it had fewer resources for war than any other great power. But the political leaders in the July crisis had only expected a brief conflict that would solve the political problems without affecting the weak political and economic structure of the monarchy.

Like German politics, Austro-Hungarian politics were still too caught up in the outdated notion of the cabinet wars of the past centuries. This strongly anachronistic cabinet policy, which simply shifted peoples and borders, was often mixed with modern politics, which apparently took into account the will of the people, but in truth was mostly just a cover, just an empty shell without content.

Despite all the inadequacies of Vienna's diplomacy, the historian Gary W. Shanafelt admits that in the situation of the First World War, even the skills of a Metternich would not have been sufficient to deal with the passions of this war and the unsolvable nationality problems of Austria-Hungary, be it through one Change of front, be it by leaving the war and taking a neutral position, to save the monarchy intact, while preserving its great power status, into the post-war period.

Italy initially remained neutral. Despite the alliance ( triple alliance ) with Austria-Hungary and the German Reich, it did not see its duty as it had been a defensive alliance and Italy had the Central Powers (which meant not the size of the power, but the situation in Central Europe ) for them Those responsible for the outbreak of war held.

Italy demanded from Austria-Hungary that Italian-speaking areas of the k. u. k. Cede the monarchy, Trentino , Trieste , Istria and parts of Dalmatia . Austria-Hungary wanted to cede Trentino ( Welschtirol ) at best . Germany recognized the danger that the Entente Italy could pull into their camp and urged Austria-Hungary to accept Italy's demands. The Entente promised more to Italy in the Treaty of London : In 1915, Austria-Hungary's former alliance partner changed sides in the hope of concluding the Risorgimento and being able to rule both coasts of the Adriatic (“mare nostro” = our sea ).

Despite the fragility of the multi-ethnic state , the Austro-Hungarian army fought until the end of the war. In Galicia , at the beginning of the war in the late summer of 1914, the army suffered heavy defeats against the Russian armies of attack. Irreplaceable losses already suffered in these major battles, especially the k. u. k. Officer corps . There was even a temporary fear that the Russians might penetrate as far as Vienna. The Russian threat to Hungary and other vital areas of the monarchy could only be averted from spring 1915. The German ally went on the offensive with strong forces on the Eastern Front and finally forced the Russians to withdraw from Galicia and give up Poland . However, the situation worsened again in the summer of 1916 when the k. u. k. Army faced the Brusilov offensive of the resurgent tsarist empire. Again the German Reich supported the beleaguered alliance partner in dire straits, a Russian breakthrough could be prevented. In 1916/17 the new enemy, Romania, was defeated with decisive German help. The great danger for the southern flank of the Danube Monarchy that had arisen in the late summer of 1916 was thus eliminated.

Serbia, considered easy prey by the Viennese “War Party”, put up bitter resistance in 1914 against three offensives of the Danube monarchy. Severely weakened, it could only be defeated in autumn 1915 with German and Bulgarian help and was occupied , opening up the land connection to the Ottoman allies. In January 1916, Montenegro was also conquered and occupied .

Italy did not succeed in twelve battles of the Isonzo in the allegedly “soft abdomen” of the k. u. k. Invade monarchy; on the contrary, after the 12th battle the Austro-Hungarian troops advanced to the Piave in northern Italy with the support of the German 14th Army . Italy was also unsuccessful in the mountain war in the Dolomites in South Tyrol . The Adriatic was more of the k. u. k. Navy ruled as by Italy.

Allied soldiers prisoners of war were held in the large Sigmundsherberg and Feldbach camps in what is now Austria . Large internment camps were located in Drosendorf , Karlstein an der Thaya and Grossau . Not only prisoners of war, but also “unreliable” citizens of Austria-Hungary were interned. Russophile Ruthenians from Galicia, Bukovina and Carpathian Ukraine , for example, were deported to the Thalerhof and Theresienstadt camps, where many of them died.

The hope cherished in 1917 that the armistice with Russia, which was followed by the October Revolution there that same year , would lead to a victory for the Central Powers, was not fulfilled due to the armed forces of the United States that had meanwhile arrived .

The superiority of the German Reich, which was able to raise significantly more people, raw materials and weapons for the war, left the k. u. k. During the war, the monarchy came under the influence of the German General Staff . Even after the USA entered the war in 1917, the latter refused to admit on the side of the Entente that the war could no longer be won. The half-hearted efforts for peace made by Emperor Charles I therefore remained in vain. His attempts to enforce universal, equal and direct suffrage in Hungary also failed because of the increasing radicalization of the Hungarian elite.

In the hinterland there were major supply crises and strikes in 1918, and sailors mutinied in the Bay of Kotor in Dalmatia.

End of the dual monarchy

When the Reichsrat , the parliament of the Austrian half of the empire, was convened again on May 30, 1917 after more than three years of government without a parliament, members of the Crown Lands made commitments to nation states:

The Poles of Galicia wanted to join a newly emerging Polish state, the Ukrainians of Galicia by no means came under Polish rule. The Czechs wanted a Czechoslovak state, the Slovenes and Croats wanted to form a South Slav state with the Serbs .

The German Bohemians and German Moravians did not want to recognize the earlier Bohemian constitutional law invoked by the Czechs, because they feared that they would come under Czech rule as a minority in the countries of the Bohemian Crown.

In Hungary , the non-Magyar nationalities could hardly articulate themselves, as they were hardly represented in the Budapest Reichstag due to the anti-minority Hungarian suffrage and all other expressions were subject to war censorship. Slovaks , Romanians and Croatians saw little reason to continue to live under Magyar suzerainty.

A way out of this legal and political deadlock was at war nor find as 1914. On October 16, 1918 Charles I, acting on a proposal from the Imperial and Royal Government under Hussarek-Heinlein for Cisleithania the peoples manifesto . This manifesto was intended to give the impetus to transform the Austrian half of the empire into a confederation of free peoples under the auspices of the emperor . The nationalities of Austria were called upon to form their own national councils ( representatives of the people ).

The Hungarian Wekerle government , which thoroughly misunderstood the situation, strictly rejected the manifesto; however, on October 18, with the consent of King Charles IV, it announced that it would introduce a legislative proposal in the Reichstag on personal union with Austria. The Real Union , which had existed since the Compromise of 1867, was thus to be ended; the Magyars wanted to break all political ties with Austria. The nationality issues of Austria could not be separated from those of Hungary: The Croats in Austrian Dalmatia wanted to found the South Slav state with the Croats of Hungarian Croatia, the Austrian Czechs Czechoslovakia with the Hungarian Slovaks.

The attempt made with the manifesto to reorganize the k. u. k. Enabling a monarchy under at least nominal leadership by the House of Habsburg-Lothringen had to fail. National desires were far stronger than remnants of dynastic loyalty.

On October 21, 1918, the German members of the Reichsrat formed the Provisional National Assembly for German Austria with reference to the Emperor's manifesto . On October 30, the National Assembly, chaired by Karl Seitz, named its 20-member executive committee the State Council (chair: also Seitz; State Chancellor: Karl Renner ), which appointed the 14 heads of the Renner I state government , which took over the state offices (the later ministries) directed.

On October 28, 1918, the Czechs in Prague took over from the previous k. k. Authorities bloodlessly seized power and proclaimed the Czechoslovak Republic ; Members of the Czechoslovak National Council took over the management of the Lieutenancy , the Provincial Administrative Commission, the police and the War Grain Transport Authority.

Slovenes and Croats became co-founders of the new South Slav state on October 29th . Romania took power in Transylvania ( Hungarian-Romanian War ). As of October 31, 1918, the Hungarian government terminated the Real Union with Austria, which dissolved Austria-Hungary.

The joint Foreign Minister Gyula Andrássy the Younger resigned on November 2, the joint Finance Minister Alexander Spitzmüller resigned on November 4, 1918. The joint Minister of War Rudolf Stöger-Steiner von Steinstätten worked after November 11, 1918 under the supervision of the German-Austrian Council of State Liquidation of the k. u. k. Ministry of War with.

On November 11, 1918, Karl I (who had been referred to as “the former emperor ” by individual media a week earlier ) was defeated by the republican-minded German-Austrian top politicians and his last k. k. Encouraged government to forego “any share in state affairs”; he had refused the formal abdication . On the same day, the emperor dismissed the k. k. Government of Prime Minister Heinrich Lammasch (it had already been referred to as the " Liquidation Ministry " on October 26th ). The last meeting of the Reichsrat took place in Vienna on November 12, 1918, and on the same day the Provisional National Assembly for German Austria proclaimed a republic . On November 13, the last Habsburg monarch, King Charles IV of Hungary, made the same waiver. Hungary became a temporary republic three days later and then remained a kingdom without a king.

In two treaties - the Treaty of Saint-Germain in 1919 with Austria and the Treaty of Trianon in 1920 with Hungary - the assignments and boundaries of the successor states of the dual monarchy were officially established.

The treaties confirmed the recognition under international law of the new states of Hungary, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (SHS state, from 1929 Kingdom of Yugoslavia ) as well as assignments of territory to Italy and Romania. German Austria was banned from joining the new German republic . In the treaty, the term “German” was deliberately not used in the state name: The treaty was therefore concluded with the “Republic of Austria”, the state name “German Austria ” , which had been used until then , no longer appeared. In favor of Czechoslovakia, Romania, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes as well as Austria, Hungary had to forego two thirds of the previous national territory and dethrone the Habsburgs.

Which states are now considered to be the successor states of Austria-Hungary in the sense of international law is often presented contradictingly in the specialist literature. For example, the dictionary of international law only ascribes German Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and the SHS state to be the succession states of the defunct Austro-Hungarian monarchy, while Romania, Poland and Italy, which are also referred to in other sources as successor states, because of their previous ones already existing statehood are not included.

The many irredentists who ultimately led to the dissolution of the monarchy were ultimately successful after Mark Cornwall because the Habsburgs had failed to “keep their own house in order”.

October / November 1918: chronology of decay

- September 29th: Massive attack by the Entente on the Western Front; thereupon the deputy German army chief Erich Ludendorff demands immediate armistice negotiations from his government. Bulgaria , ally of the Central Powers, concludes an armistice. On the Italian front the k. u. k. Troops starving, lack of supplies, exhaustion and desertion. The centrifugal forces of Austria-Hungary see increased chances of success.

- October 6: Formation of the National Council of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs . The royal Hungarian government in Budapest loses its authority in Agram .

- October 16: Emperor Karl I signs the k. k. The Hussarek-Heinlein government drafted the “ People's Manifesto ” to rebuild the Austrian Empire into a federation of independent nation states. The goal of the politicians of the nationalities is independence .

- October 21: The German Reichsrat members of Austria elected in 1911 form the Provisional National Assembly for German Austria in Vienna .

- October 24th: The k. k. The government in Vienna has lost its authority. Some of your orders are no longer followed. The Hungarian Diet in Budapest, with the consent of King Charles IV, at the request of the Royal Hungarian Government Sándor Wekerle, declares the Austro-Hungarian settlement of 1867 to have expired on October 31. At the request of the Entente, Italy started the last decisive offensive on the Italian front with the Battle of Vittorio Veneto .

- October 26th: Charles I dissolves the alliance with the German Empire.

- October 27: Appointment of the "Liquidation Ministry" Lammasch in Vienna by Karl I. The swearing-in takes place the following day.

- October 28: The Czechoslovak National Committee in Prague takes over the administration of Bohemia from the k. k. Lieutenancy and resolves the establishment of the independent Czechoslovak state . Galicia breaks away from the Austrian Empire in order to belong as West Galicia to the re-emerging Polish state and as East Galicia to the newly founded West Ukrainian People's Republic . The so-called aster revolution begins in Hungary .

- October 29th: The Moravian National Committee takes over the management of the k. k. Lieutenancy and the military command authorities in Brno . The Croatian state parliament declares Croatia's exit from Austria-Hungary. In Agram , the state of the Slovenes, Croats and Serbs (SHS state) is proclaimed, to which all southern Slavic areas of the previous monarchy should belong. The Slovenian National Council in Ljubljana declares the areas populated by Slovenes independent of Austria. The Austro-Hungarian Army High Command initiates armistice negotiations with Italy.

- October 30: Emperor and King Karl I./IV. gives the order that k. u. k. Hand over the Kriegsmarine to Croatia. The Provisional National Assembly for German Austria appoints the first cabinet , which constitutes German Austria as a state; Karl Renner becomes State Chancellor. The Czechoslovak National Committee takes over the k. u. k. Military command in Prague, Pilsen and Leitmeritz .

- October 31: The National Council in Ljubljana declares Slovenia's accession to the SHS state. The representatives of the Romanians in the Kingdom of Hungary declare the accession of Transylvania to the Kingdom of Romania . The former Royal Hungarian Prime Minister István Tisza is murdered in Budapest. South Slav officers take command of the Navy.

- November 1st: The k. k. The Lammasch government in Vienna begins to hand over the business to the German-Austrian government Renner. The administration of Bosnia is handed over to its National Committee. The management of the k. k. Police Directorate Vienna is sworn in on the German-Austrian State Council.

- November 2: The previously deposited order from the new Defense Minister of the Hungarian government, Mihály Károlyi , Béla Linder, to the Hungarian regiments on the Italian front to cease fighting and lay down their arms is officially passed on to the troops by the Army High Command. The last k. u. k. Foreign Minister, Gyula Andrássy the Younger , resigns.

- 3rd / 4th November: Armistice at Villa Giusti near Padua between the armed forces of Austria and Hungary and the Entente. The date of the coming into force urgently awaited by the army will be postponed to 24 hours before the signing at Italian request and will no longer reach the troops in time; this enables Italy to capture hundreds of thousands of Austrian soldiers at the last minute. Italy occupies Tyrol south of the Brenner Pass , Trieste and the Austrian coast . The last joint finance minister, Alexander Spitzmüller , resigns.

- November 6th: Karl I./IV. orders the demobilization of the remaining units of the army. German troops occupy parts of Tyrol and Salzburg from November 6th to 10th.

- November 11: Emperor Karl I renounces the government in German Austria, dismissal of the k. k. Lammasch government, release of all officials from the imperial oath of allegiance. The last k. u. k. Minister of War, Rudolf Stöger-Steiner von Steinstätten , resigns.

- November 12: The state of German Austria declares itself a republic and part of the German republic by resolution of its provisional national assembly . The delegations and the mansion of the Reichsrat as well as the k. u. k. and k. k. Ministries are dissolved.

- November 13: King Charles IV resigns from Hungary. The Hungarian government, which took place on 3./4. If the armistice that came into force on November 11th was not affected, since Hungary ended the Real Union with Austria at the end of October 1918, a military convention was concluded in Belgrade that worsened Hungary's armistice conditions.

- November 14th: Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk , still out of the country, is elected President of the Czechoslovak Republic. His designation by the Czech politicians in exile had already taken place on October 24 in Paris.

- November 16: Hungary declares itself a republic, Károlyi becomes the first president.

- November 23: Italian troops occupy the Tyrolean capital Innsbruck .

- November 28th: Bukovina , "stateless" after the collapse of Old Austria , is annexed by the Kingdom of Romania.

- December 1st: In front of 100,000 Hungarian Romanians gathered in Alba Iulia (Karlsburg), the “Great National Assembly” proclaimed in the “Karlsburger Decisions” the annexation of Transylvania, the Banat and other Hungarian regions to Romania.

(References)

Aftermath of Austria-Hungary in the present day

Classification of Austria-Hungary in the successor states

In the first decades after the end of the k. u. k. Monarchy was often referred to by critics as the “people dungeon” and “doomed”. The successor states saw their common history before 1918 primarily under the aspect of the oppression and prevention of self-determination of the nationalities . The catchwords “people dungeon”, but also “Germanization” with regard to the Habsburg Monarchy, were used in the southern Slavic region from 1918 and increasingly after 1945 and remained in public memory and discourse until the 1990s. In contrast, Winston Churchill described the destruction of Austria-Hungary as a great tragedy, because for centuries this empire enabled a large number of peoples to benefit from trade and security or a common life, and after its disintegration none of these peoples could survive the pressure of Germany or Russia .

At the latest since the accession of most of the successor states to the EU , it is again possible to speak impartially about the positive aspects of the former common state: the large common economic area, the free movement of persons, the civil rights, the modern judiciary and administration at that time and the gradual political emancipation of the poorer sections of the population. Because after the turmoil of the interwar period, increasing anti-Semitism and racism, the Second World War , the Holocaust and four decades of communist dictatorship, these achievements are often assessed differently than before. Most of the inhabitants of the dual monarchy, despite many shortcomings (mass poverty or nationality problems or Magyarization ) associated with the Habsburg monarchy state education, the beginning of simple social assistance, a general health system, extensive religious tolerance, the rule of law and the maintenance of a developed infrastructure. Most of the minority activists also recognized the importance of the Austro-Hungarian community as a system of collective security, with great differences between the Austrian and Hungarian parts of the empire. These characteristics of the Habsburg monarchy were remembered for a long time.

The “Habsburg effect” is said to still shape the residents on this side of the former borders. Former institutions of the monarchy therefore continue to work through cultural norms after several generations. People living on the former territory would have measurably more trust in local courts and police and also pay less bribes for public services than their compatriots across the old border.

In the successor states of the dual monarchy, the railway network that was established in 1918 is still largely in operation today. In many places there are still public buildings (from the theater to the train station) in the typical architectural style of the period before 1918. The legacy of the monarchy is also evident in the history of science and culture .

Economic and political forms of cooperation

Critics of today's Austrian foreign policy complain that cooperation with Austria's neighboring states in the north, east and south-east has not played an essential role since 1989. This contrasts with very substantial investments by Austrian companies in these neighboring countries. In addition, within the European Union there are particularly intensified cooperations between countries in the area of the former monarchy. The Visegrád states have been striving for greater political and economic cooperation with one another since 1991.

Consequences of migration movements and cultural identification

As a result of two world wars and the subsequent Cold War, millions of families are English speaking, former Austro-Hungarian families as refugees, expellees and ethnic German immigrants in the Federal Republic of Germany reached where they have since established their descendants and for the most part of the regional majority population assimilated have . The proportion of these families in West Germany was welcomed, is far greater than the sedentary become in Austria part, although after the collapse of the monarchy, the Republic of Austria - and in particular the city of Vienna - often has always been a cultural center of the German- old Austrian viewed has been. Other families have emigrated to other countries such as the USA , Canada , Israel and Australia .

Parts of the empire and countries

| Division of Austria-Hungary |

|---|

|

|

Cisleithanien 1. Bohemia 2. Bukovina 3. Carinthia 4. Carniola 5. Dalmatia 6. Galicia and Lodomeria 7. Gorizia and Gradisca; Trieste with territory; Istria 8. Austria under the Enns 9. Moravia 10. Salzburg 11. Austrian-Silesia 12. Styria 13. Tyrol 14. Austria above the Enns 15. Vorarlberg |

|

Transleithanien 16. Hungary (with Vojvodina and Transylvania ) 17. Croatia and Slavonia |

| (18.) Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| rank | city | Residents |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Vienna | 2,083,630 |

| 2. | Budapest | 880.371 |

| 3. | Trieste | 229.510 |

| 4th | Prague | 223,741 |

| 5. | Lviv | 206.113 |

| 6th | Krakow | 151.886 |

| 7th | Graz | 151.781 |

| 8th. | Brno | 125,737 |

| 9. | Szeged | 118,328 |

| 10. | Maria Theresiopel | 94,610 |

The Leitha river formed the border between the two halves of Austria and Hungary (corresponds to today's western border in Burgenland ). The names Cisleithanien ("Land this side of the Leitha" for the western half of the empire) and Transleithanien ("Land beyond the Leitha" for the eastern half of the empire) were derived from this: Cisleithanien was officially called the kingdoms and countries represented in the imperial council (previously unofficially, since 1915 officially called Austria); those individual countries were called Crown Lands and the Transleithan countries were officially called The Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown of St. Stephen . The countries of the monarchy formed semi-autonomous states and had a centuries-old history. Before they were acquired by the Habsburgs, they formed partly independent states and since the February patent of 1861 they again had several state institutions of their own. Head of State was always personal union of the emperor and king, by a state leader or country President was represented.

The country of Bosnia and Herzegovina , which previously belonged to the Ottoman Empire, was administered jointly by both halves of the empire. It was occupied in 1878 and incorporated into the Reich Association in 1908, accepting the Bosnian annexation crisis . The following tables show the results of the census of December 31, 1910.

In contrast to many other European great and medium powers, Austria-Hungary had no colonial ambitions. The only non-European colonial possession of the dual monarchy existed between 1901 and 1917 in a small concession in the Chinese city of Tianjin (Tientsin) . The Empire of China had to cede this area due to Austria-Hungary's successful participation in the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion in 1900 . The concession was on the eastern bank of the Hai He (Peiho) , covered an area of approximately 62 hectares and had around 40,000 inhabitants. In the south the area was bounded by the Italian concession, in the east by railway facilities, in the north and west by Hai He. It was administered by the respective k. u. k. Consul, who was supported in his duties by a small military garrison, among other things. In addition to the consulate and barracks, there was also a prison, a school, a theater and a hospital in the area of the concession. When China declared war on the Central Powers in August 1917, the territory was re-incorporated into the Chinese state. In September 1919 Austria finally gave up any claim to the territory with the signing of the Treaty of Saint-Germain (Article 116). Hungary followed suit in June 1920 with an article of the same name in the Treaty of Trianon .

| country | Area in km² | Residents | Capital | Pop. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kingdom of Bohemia | 51,946.09 | 6,769,548 | Prague | 224,000 |

| Kingdom of Dalmatia | 12,830.32 | 645,666 | Zara / Zadar | 14,000 |

| Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria | 78,499.28 | 8,025,675 | Lviv | 206,000 |

| Archduchy of Austria under the Enns | 19,825.33 | 3,531,814 | Vienna | 2,031,000 |

| Archduchy of Austria above the Enns | 11,981.73 | 853.006 | Linz | 71,000 |

| Duchy of Bukovina | 10,441.24 | 800.098 | Chernivtsi | 87,000 |

| Duchy of Carinthia | 10,325.79 | 396.200 | Klagenfurt | 29,000 |

| Duchy of Carniola | 9,953.81 | 525.995 | Laibach | 47,000 |

| Duchy of Salzburg | 7,153.29 | 214.737 | Salzburg | 36,000 |

| Duchy of Upper and Lower Silesia | 5,146.95 | 756.949 | Troppau | 31,000 |

| Duchy of Styria | 22,425.08 | 1,444,157 | Graz | 152,000 |

| Margraviate of Moravia | 22,221.30 | 2,622,271 | Brno | 126,000 |

| Fürstete Grafschaft Tirol 2 | 26,683 | 946.613 | innsbruck | 53,000 |

| Princely county of Gorizia and Gradisca 1 | 2,918 | 260.721 | Gorizia | approx. 25,000 |

| Imperial City of Trieste and its territory 1 | 95 | 229.510 | Trieste | 161,000 |

| Margraviate of Istria 1 | 4,955 | 403,566 | Parenzo / Poreč | approx. 4,000 |

| Vorarlberg 2 | 2,602 | 145.408 | Bregenz | 9,000 |

| Cisleithania overall | 300,003.21 | 28,571,934 | Vienna |

| country | Area in km² | Residents | Capital | Pop. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kingdom of Hungary (including the city of Fiume and its territory ) |

282,274.66 | 18,264,533 | Budapest | Inner city 882,000 with suburbs 1,290,000 |

| Kingdom of Croatia and Slavonia | 42,488.02 | 2,621,954 | Agram | 80,000 |

| Transleithania in total | 324,762.68 | 20,886,487 | Budapest |

| country | Area in km² | Residents | Capital | Pop. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 51.199 | 1,898,044 | Sarajevo | 52,000 |

| Realunion | capital Cities | Area in km² | Residents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austria-Hungary | Vienna and Budapest | 675,964.89 | 51,356,465 |

politics

| 10 messages |

|---|

|

|

| 19 embassies |

|

|

| 2 missions |

|

|

Constitution

There was no common constitution for the dual state. The legal basis of the Danube Monarchy was formed by the following three laws, which - with the same wording - were valid in Austria and Hungary:

- the Pragmatic Sanction of Emperor Charles VI. from April 19, 1713,

- the Constitutional Law (then unofficially called Delegation Law ), for Cisleithanien ( Austria ) as part of the December constitution of December 21, 1867, in Hungary (Transleithanien) previously announced with Law XII / 1867, and

- the customs and trade alliance of June 27, 1878.

The pragmatic sanction was a succession regulation and had - since Charles VI. had no male descendants - the effect of establishing the rulership rights of his daughter Maria Theresa and her descendants. The delegation laws of Austria and Hungary stipulated which affairs the two states had to conduct jointly. The customs and trade alliance with a common currency, mutual freedom of establishment and mutual informal recognition of company and patent registrations was a voluntary agreement between the two states.

The Emperor of Austria was also King of Hungary and thus King of Croatia and Slavonia at the same time. This now happened in Hungary's own law and no longer derived from the Austrian imperial dignity .

The common affairs according to the delegation laws, foreign policy and the army , were administered by common ministries: Foreign, War and Treasury; this not for the entire finances of the dual monarchy, but only for the financing of common affairs. This construction was called Realunion . Institutions that affected both halves of the empire were labeled “k. u. k. "(" k aiserlich and k öniglich ") refers to.

The government of Cisleithanien was named "k. k. ”(“ k aiserlich- k önlichen ”), whereby royal referred to the bohemian royal dignity that the Austrian emperor also held. The government and institutions of the Hungarian half of the empire were awarded “kgl. ung. ”(“ royal Hungarian ”) or“ m. kir. ” (magyar királyi) .

The ruler title and state name determined by the emperor and king after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 on November 14, 1868:

- For contracts concluded in the name of the emperor :

Emperor of Austria and Apostolic King of Hungary - Personal designation:

His k. u. k. Apostolic Majesty - State name:

Austro-Hungarian monarchy ; the first time in a treaty with the June 2, 1868 Sweden and Norway used

The name Austria was used sparingly in domestic state practice, probably out of consideration for the non-German majority in the Austrian Empire. On the one hand, the Basic State Law of December 21, 1867 regulated that “all members of the kingdoms and countries represented in the Imperial Council ... a general Austrian citizenship right ” (in Hungary, citizenship law was equally inclusive). On the other hand, the national territory was often referred to as “the kingdoms and countries represented in the Imperial Council”, a formula for embarrassment that was always replaced by Austria outside of official texts . Only in 1915 was this officially determined.

Rulers and common ministries

The monarch (see personal union) ruled in Cisleithanien as Emperor of Austria , in Transleithanien as Apostolic King of Hungary.

|

|

|

|

Hungarian Crown of St. Stephen

|

- Franz Joseph I. 1867–1916

- June 8, 1867 coronation as King of Hungary (I. Ferenc József)

- Died November 21, 1916

- Charles I./IV. 1916-1918

- November 21, 1916 with the death of his predecessor automatically emperor and king

- December 30, 1916 coronation as King of Hungary as Charles IV. (IV. Károly)

- November 11, 1918 renunciation of government in the Austrian half of the empire (no abdication)

- November 13, 1918 renunciation of government in the Hungarian half of the empire (no abdication)

At Franz Joseph's instigation , foreign policy, the army and navy were administered in kuk joint ministries, which were responsible for both halves of the empire , in the spirit of a real union , as agreed in the settlement of 1867 ; the ministers were appointed by the monarch and could not be ministers of either state at the same time. Austria-Hungary as a whole had no head of government :

- Minister of the Imperial and Royal Houses and of Foreign Affairs , also Chairman of the Joint Council of Ministers

- (Reich) Minister of War

- Reich finance minister or joint finance minister (only to finance joint affairs)

Each half of the empire also had its own national defense ministry , which was responsible for the respective Landwehr - imperial-royal Landwehr or royal Hungarian Landwehr . The Joint Supreme Audit Office exercised the financial control in common matters. However, there were no common courts for both parts of the empire. Political agreements and political control over foreign and military policy were the responsibility of the 60-person delegations elected by the Austrian Reichsrat and the Hungarian Reichstag , which met annually, alternately in Vienna and Budapest.

Prime Minister

From 1867 on, each of the two halves of the empire had its own prime minister , who, like his ministers, was appointed and removed by the monarch. Due to the constitutional and the real political development of the Habsburg Monarchy , the Austrian Prime Minister solely on the will of the emperor remained dependent (a no-confidence vote , which the resignation committed, there was in the Reichsrat not), the Hungarian Prime Minister on the will of the king and the Hungarian aristocracy . In the Austrian half of the empire in particular, officials changed frequently from the early 1890s onwards; only a few politicians could gain formative influence:

- k. k. Prime ministers of the kingdoms and states represented in the Imperial Council (Cisleithanien)

- Ku Prime Minister of the countries of the Hungarian Crown (Transleithanien)

Military affairs

The military system of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy and the two (sub) states had been based on the principle of the universal and personal obligation of every citizen to carry arms since 1868.

The armed forces consisted of the common army (k. U. K. Army) , the land forces of both states and the navy .

Commander-in-chief was the Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary, who z. B. signed every promotion of an officer himself. Administratively, the common armed forces were the Reichs and k. u. k. Subordinated to the war ministry, the technical management had the chief of staff, who reported directly to the monarch.

The two Landwehr departments were subordinate to the Landwehr Ministry of Cisleithania and Transleithania . A comprehensive restructuring of the common army did not come about until the First World War from 1914 to 1918.

The Austro-Hungarian armed forces broke up like the dual monarchy in 1918. On October 31, 1918, Hungary declared the end of the Real Union with Austria, thus making the common structures and tasks that had existed since 1867 obsolete. Hungary set up its own war ministry and immediately recalled the Hungarian regiments from the Italian front .

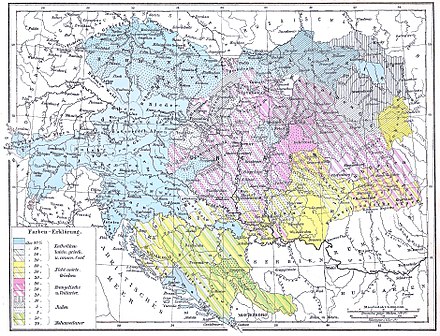

Languages and religions

In the 1910 censuses, the colloquial language was determined in Austria-Hungary . In old Austria, Jews mostly stated German as their colloquial language, as did civil servants who, although not having German as their mother tongue, spoke mainly German due to their involvement in the administrative apparatus. Exact numbers about the national allocation do not exist.

See also: Bohemian language conflict

| language | Absolute number | percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| German | 12.006.521 | 23.36 | |

| Hungarian | 10,056,315 | 19.57 | |

| Czech | 6,442,133 | 12.54 | |

| Polish | 4,976,804 | 9.68 | |

| Croatian and Serbian | 4,380,891 | 8.52 | |

| Ukrainian (Ruthenian) | 3,997,831 | 7.78 | |

| Romanian | 3,224,147 | 6.27 | |

| Slovak | 1,967,970 | 3.83 | |

| Slovenian | 1,255,620 | 2.44 | |

| Italian | 768.422 | 1.50 | |

| Others | 2,313,569 | 4.51 | |

| All in all | 51.390.223 | 100.00 | |

| country | Main colloquial language | other languages (more than 2%) |

|---|---|---|

| Bohemia | Czech (63.2%) | German (36.8%) |

| Dalmatia | Croatian (96.2%) | Italian (2.8%) |

| Galicia | Polish (58.6%) | Ukrainian (40.2%) |

| Lower Austria | German (95.9%) | Czech (3.8%) |

| Upper Austria | German (99.7%) | |

| Bucovina | Ukrainian (38.4%) | Romanian (34.4%), German (21.2%), Polish (4.6%) |

| Carinthia | German (78.6%) | Slovenian (21.2%) |

| Carniola | Slovenian (94.4%) | German (5.4%) |

| Salzburg | German (99.7%) | |

| Austrian Silesia | German (43.9%) | Polish (31.7%), Czech (24.3%) |

| Styria | German (70.5%) | Slovenian (29.4%) |

| Moravia | Czech (71.8%) | German (27.6%) |

| Tyrol | German (57.3%) | Italian (42.1%) |

| Coastal region (= Trieste, Gorizia, Istria) | Slovenian (37.3%) | Italian (34.5%), Croatian (24.4%), German (2.5%) |

| Vorarlberg | German (95.4%) | Italian (4.4%) |

Religions

The following table shows the distribution of religions in Austria-Hungary. While the Austrian half of the empire was predominantly Catholic (mostly Roman Catholic, in eastern Galicia also Greek Catholic ), there was a numerically significant Protestant (mostly Reformed) minority in eastern Hungary. The Jewish population was concentrated in the eastern parts of the country, particularly in Galicia, where it averaged about 10%. The German-speaking Alpine countries originally had only a vanishingly small Jewish population, but the Jewish population in the rapidly growing metropolis of Vienna increased sharply due to immigration from the east of the monarchy and was around 8.8% in 1910. Other cities with a high proportion of Jewish populations were (1910): Budapest (23.4%), Prague (9.4%), Lviv (28.2%), Krakow (28.2%), Chernivtsi (32.4%) . In 1910 1,225,000 Jews lived in Cisleithanien , 911,227 in the Kingdom of Hungary and 21,231 in the Kingdom of Croatia and Slavonia. They made up 4.7% of the total population in Austria and 5.0% in the Hungarian half. In Croatia and Slavonia 0.8%. In Bosnia-Herzegovina about a third of the population was of Islamic faith.

The Jewish population in Austria-Hungary had largely experienced tolerance in comparison to the countries in the east and south-east, despite the increasing anti-Semitism . The Jews in the monarchy had been emancipated under the long reign of Franz Joseph and viewed him as a patron. He has even been ascribed a philosemitic inclination. Fanatical anti-Semites even referred to Franz Joseph as "Jewish Emperor" when he often refused to appoint Karl Lueger because of his anti-Semitic polemics as mayor of Vienna.

| Religion / denomination | total | Austrian half of the empire |

Hungarian half of the empire |

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catholics | 76.6% | 90.9% | 61.8% | 22.9% |

| Protestants | 8.9% | 2.1% | 19.0% | 0.0% |

| Orthodox | 8.7% | 2.3% | 14.3% | 43.5% |

| Jews | 4.4% | 4.7% | 4.9% | 0.6% |

| Muslims | 1.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 32.7% |

Nationality problem and reform concepts

Since the revolutionary year of 1848 at the latest, the nationality problem in the Habsburg Empire developed into a question of existence due to growing nationalism, which was also increasingly taking hold of the supposedly “historically free” nations. In a Europe of emerging nation-states, in which nationalism was perceived as the absolute strongest political force, the multinational, multiethnic state in the eyes of most Europeans, but also of many of its inhabitants, developed more and more into an anachronism that was not viable . The Danube Monarchy was characterized by its opponents as a “prison of nations” from which it was necessary to free oneself. The question of whether the nationality problem of the Habsburg Empire was solvable at all is generally answered in the affirmative rather than in the negative.

Some reform concepts to save the monarchy have been developed, often impractical and impractical. One of these concepts was actually implemented in 1867: the settlement with Hungary. The realization of the dualism was born out of the hardship into which the German supremacy in Austria had gotten after the defeats in the Italian and German wars. With Germany and Italy, two new nation states had emerged, in the Danube Monarchy only a pure balance of power was carried out with the Magyars. The rule over the other peoples of the monarchy, who made up a majority in the population, was divided between them and the German Austrians. As the most developed nation alongside the Germans, the Hungarians had also been given a position of priority which they defended most tenaciously and relentlessly in the following decades. Until the final collapse of the monarchy, Hungary even became one of the most reactionary states in Europe due to its policy of forced Magyarization and its undemocratic suffrage. Hungary was a pseudo-nation-state ; despite its mixed national composition, it was governed like a nation-state.

In Cisleithanien, the judiciary and administration showed a much more tolerant treatment of the Slavic and Romance nationalities, “even if the Austrian administrative policy towards the Slovenes in southern Styria and, until shortly before the outbreak of war, also in Carniola, as well as the excesses of Pan-Germanism in Bohemia are often used as counterexamples could ". The poorer treatment of nationalities in Hungary was not due to the constitution, but to the practice of the authorities, to the failure of the judiciary, administration and politics.

Since the conditions in the Austrian half of the empire, especially between Germans and Czechs, were getting worse and worse, the demands for a reorganization of the monarchy became more and more urgent. The South Slav trialist program was at the forefront of reform plans for most of the last two generations of the Habsburg Empire, although in its conservative form the Slovenes were not included. In addition to the Austrian and Hungarian parts of the empire, a South Slavic empire was to emerge under Croatian leadership, the strongest South Slavic group in the empire in terms of numbers and historical tradition. This South Slav state was intended to weaken Hungary on the one hand and counteract Greater Serbian ambitions on the other in the interests of the entire empire. The Trialism however rule out a more comprehensive solution to the nationality problem. Croatian trialism, like Hohenwart's plan for the reconciliation of the Czechs in 1871, only considered the national status of a single ethnic group . However, the Austrian nationality question was so involved that the treatment of one of these questions obviously influenced that of all the others.

In the last decades of the monarchy, the concept of trialism, due to the Serbian and associated South Slavic antagonism , apart from its natural rejection by Hungary, had little chance of being realized. While trialism had, alongside Croatian conservative circles, the heir to the throne Franz Ferdinand as a sponsor, his reform plans soon developed in the direction of comprehensive federalization . His anti-Hungarian plans related primarily to the Hungarian nationalities, not because they were socially and politically disadvantaged, but because he considered them loyal to the state. However, this goal could hardly be achieved by the Crown Land federalism, initially favored by Franz Ferdinand, which did not take ethnic conditions into account.

Ultimately, the heir to the throne became the focal point of the Greater Austrian movement , which envisaged a federalization of all the peoples of the empire on an ethnic basis, although ultimately he could not fully agree with their most pronounced ideological support, Popovici's federalization concept . Franz Ferdinand technically never committed himself to any of these plans; his intentions sometimes contradicted each other and were often vague. He followed a zigzag course between an ethnic and a historical-traditional federalism, occasionally reverted to trialism and advocated a kind of watered-down centralism.

In 1905 four state laws were passed in Moravia with the Moravian Compromise , which were intended to guarantee a solution to the German-Czech nationality problems and thus to bring about an Austrian-Czech compensation .

The well-known principle of personality by Karl Renner envisaged a territorial division into circles, with the autonomous status referring to the individual individuals.

In essence, the nationality struggle before 1914, even in its radical forms, with the exception of Pan-German, Serbian and partly Italian and Ruthenian propaganda, was primarily concerned with the reform of the empire and not with the aims and methods that were to lead to its dissolution . But in 1914 the monarchy was still a long way from achieving a truly mutually satisfactory national compromise. Since a possible Habsburg federal state would have mostly consisted of mere torsos of nations, the federalization concepts also had to fail.

The historian Pieter M. Judson argues that nationalist propaganda in Austria-Hungary was essentially only carried out by parts of the respective national educated elite and that it hardly had any effect on the general population until the First World War. The loyalty of the population, however, was due to the Habsburg dynasty and the rule of law institutions of the empire: "The existence of nationalist movements and conflicts did not weaken the state in a life-threatening manner and certainly did not lead to its collapse in 1918". The narrative of the Habsburg Empire as a “people's dungeon” was merely a subsequent strategy of justification by politicians in the successor states.

Magyarization Policy in Hungary

After the settlement with Austria there was a Hungarian-Croatian settlement within the Hungarian half of the empire , in which Croatia and Slavonia were granted limited autonomy. In other parts of Hungary, however, ethnic tensions increased.

The reasons for these tensions were both the Hungarian government's policy of Magyarization and the increase in intolerance between nationalities. In contrast to the minorities living in the Kingdom of Hungary such as Slovaks or Romanians , the nationalism of the Magyars had state power on its side and was thus in the stronger position, although the ethnic Hungarians only made up about half of the population.

The implementation of minority legislation, which is essentially liberal, had little success in such an atmosphere. The Nationalities Act of 1868 determined Hungarian as the state language, but allowed minority languages at regional, local and church levels. But this regulation was often not put into practice and the minorities faced assimilation attempts. From 1875, under Prime Minister Kálmán Tisza (1875–1890), a consistent policy of Magyarization was pursued in order to “make all non-Magyars Hungarians in 40 years”.

As early as the revolutionary year of 1848, Slovak members of the Hungarian parliament took the initiative to get support from the emperor against the Magyarization policy. A declaration was made with “demands of the Slovak nation”, which was given to the emperor and the Hungarian national government. Demands were made for the federalization of Hungary, the constitution of an ethnic-political unit, the definition of the Slovak borders, a separate state parliament, a Slovak national guard, national symbols, the right to use the Slovak language, universal suffrage and equal representation in the Hungarian parliament.

The Magyars, however, saw their position of power in Upper Hungary , as they called today's Slovakia, in danger and reacted with martial law and arrest warrants against the Slovak national leaders. Slovak governments in exile were established in Vienna and Bohemia, but the hopes of the Slovaks were disappointed. After the revolution, the Hungarians were left with their centralized administration. The Compromise of 1867 left the minorities completely at the mercy of Budapest's Magyarization policy . Between 1881 and 1901 the Slovaks had no members of their own in the Hungarian parliament, even after that it was proportionally fewer than their share of the population. Attempts by Budapest before and during the First World War to counter the Serbian and Romanian expansionist nationalism with concessions came too late.

The rigorous Magyarization policy, which was particularly successful among the Slovak and German-speaking population of Transleithania , caused the Magyar population to grow to just over half. Between 1880 and 1910 the percentage of citizens of Hungary (excluding Croatia) who professed to be Magyars rose from 44.9 to 54.6 percent. With the help of a reactionary suffrage that allowed only the privileged segment of the population to vote, in 1913 only 7.7% of the total population were eligible to vote (or were allowed to hold public office). A pseudo-reform shortly before the end of the war envisaged a full 13% as eligible to vote. This cemented the reactionary structure of the multi-ethnic state of Hungary.

Emigration from Austria-Hungary

Between 1876 and 1910 around 3.5 million (other figures give up to 4 million) residents of the dual monarchy emigrated. They were poor and unemployed and hoped for better living conditions in another country. About 1.8 million people came from the Cisleithan half of the empire and about 1.7 million from the Transleithan half. Almost three million of them had the United States of America as their travel destination, 358,000 people chose Argentina as their new home, 158,000 went to Canada, 64,000 to Brazil and 4,000 emigrated to Australia. The rest was spread across other countries.

In 1907 alone, around half a million people left their homeland. The governments of Austria and Hungary were concerned that there were many young men fit for work among the emigrants. Between 1901 and 1905, 65,603 properties, 45,530 of which were smaller parcels, were auctioned publicly by emigrants in Austria alone. Emigrants often wrote enthusiastically from “over there” to their friends and family members who had stayed at home - sometimes ship tickets paid for at the same time were enclosed.

The most important ports of departure for the emigrants were Hamburg and Bremerhaven, where the ships of the major shipping companies, the North German Lloyd and the Hamburg-America Line , docked. In the middle of the 19th century, a boat trip to New York with the first steamships took around a month, but around 1900 the journey time was only a week in good weather. A trip from Trieste with the Austro-Americana only took 15 days. Every year 32 to 38 trips made to the USA. The travel conditions for the mostly poor emigrants were often miserable. The emigration business was extremely lucrative and therefore highly competitive for the shipping companies, who saved on comfort for the less affluent passengers.

Most of the emigrants came from Galicia in what is now Poland and Ukraine. From 1907 to 1912 there were 350,000, as emerged from an interpellation by Polish members of the Reichsrat to various Austrian ministers on March 12, 1912.

education

In the area of general popular education, the general compulsory education led to a continuous decline in illiteracy, which was still prevalent, especially in the eastern and southern parts of the empire . However, this remained a considerable educational policy problem and hindered the participation of large sections of the population in social and political life.

| Crown land | 1880 | 1900 | Absolute decrease in illiterate 1880-1900 |

Relative decrease in the illiterate 1880-1900 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bohemia | 8.5 | 5.3 | 3.2 | 37.6 |

| Dalmatia | 87.3 | 73.6 | 13.7 | 15.7 |

| Galicia | 77.1 | 63.9 | 13.2 | 17.1 |

| Lower Austria | 8.5 | 6.0 | 2.5 | 29.4 |

| Upper Austria | 8.6 | 5.8 | 2.8 | 32.6 |

| Bucovina | 87.5 | 65.2 | 22.3 | 25.5 |

| Carinthia | 39.6 | 24.0 | 15.6 | 39.4 |

| Carniola | 45.4 | 31.4 | 14.1 | 30.8 |

| Salzburg | 11.7 | 8.7 | 3.0 | 25.6 |

| Austrian Silesia | 11.8 | 11.2 | 0.6 | 5.1 |

| Styria | 27.8 | 18.0 | 9.8 | 35.3 |

| Moravia | 10.4 | 7.8 | 2.6 | 25.0 |

| Tyrol and Vorarlberg | 9.7 | 7.1 | 2.6 | 26.8 |

| Coastal land | 56.8 | 38.2 | 18.6 | 32.7 |

| Austrian half of the empire | 34.4 | 27.4 | 7.0 | 20.3 |

| Hungarian half of the empire | 58.8 | 41.0 | 17.8 | 30.3 |

In addition to the primary school system, there was also a separate school system for the next generation of the military, which was specifically geared towards military requirements. An overview of this school can be found in the following two articles:

economy

Compared to Germany and many Western European countries, the Austrian half of the empire was economically backward, but still significantly more developed than the agrarian Hungary. The backwardness towards Germany that arose in the first half of the 19th century had its causes, among other things, in the belated liberation of the peasants in 1848 or the late freedom of trade (elimination of the guilds only in 1859, around 50 years later than Prussia). In addition, there was a protective tariff system that inhibited economic development and shielded the country from the global economy; there was even an internal customs border to Hungary.

Mining

The mining industry generated 78.81 million guilders in 1889 . The most important raw materials mined were brown and hard coal and salt. Graphite, lead and zinc were also of importance. In terms of precious metals, 3,543.5 tons of silver could be mined. Gold mining played practically no role back then - in 1889 only around 13 kilograms of gold were mined.

Petroleum industry

Austria-Hungary had considerable oil reserves in Galicia , which had been increasingly developed since the end of the 19th century. Before the First World War , the dual monarchy had the largest oil reserves in Europe and in 1912 it rose to become the world's third largest oil producer (after the USA and Russia ) with a production of 2.9 million tons .

Industry

The Austro-Hungarian economy changed significantly during the existence of the dual monarchy. The technical changes accelerated both industrialization and urbanization . While the old institutions of the feudal system disappeared more and more, capitalism spread over the territory of the Danube monarchy. First of all, economic centers developed around the capital Vienna, Upper Styria , Vorarlberg and Bohemia, before industrialization also found its way into central Hungary and the Carpathians in the further course of the nineteenth century . The result of this structure were enormous inequalities in the development within the empire, because generally the western economic regions generated far more than the eastern ones. Up until the beginning of the 20th century, the economy had grown rapidly in almost the entire national territory and the entire economic growth could well measure up to that of other major European powers, but due to the late onset of this development, Austria-Hungary continued to lag behind in international comparison. Before the First World War, the main trading partner was, by far, the German Reich (1910: 48% of all exports, 39% of all imports), followed by Great Britain (1910: almost 10% of all exports, 8% of all imports). Trade with the geographically neighboring Russia, on the other hand, was only of relatively minor importance (1910: 3% of all exports, 7% of all imports). The main trade goods were agricultural products.

In the second half of the 19th century, a mechanical engineering industry also developed in Austria-Hungary. This development is associated with the rise of companies such as Škoda from Pilsen , the Ganz-Werke and the Csepel-Werke ( Manfréd Weiss Group) in Budapest , MÁVAG in Budapest and the Austrian Arms Factory (ÖWG, later Steyr-Werke ). During the First World War, some of these companies reached considerable sizes: The ÖWG had around 15,000 and Csepel around 30,000 employees, while in 1917 Škoda had around 35,000 people under contract in Pilsen alone.