Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill KG OM CH PCc RA (born November 30, 1874 in Blenheim Palace , Oxfordshire ; † January 24, 1965 in London ) is considered the most important British statesman of the 20th century. He was Prime Minister twice - from 1940 to 1945 and from 1951 to 1955 - and led Britain through World War II . He had previously held several government offices, including that of Minister of the Interior , First Lord of the Admiraltyand the Chancellor of the Exchequer . He also emerged as an author of political and historical works and received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1953 .

Churchill came from the British aristocracy and was the son of a leading politician in the Conservative Party . After a career as an officer and war correspondent , he moved in 1901 as a member of the lower house , to which he was to belong for over 60 years. After moving from the Conservatives to the Liberals in 1904, he successively took over various government offices. As First Lord of the Admiralty, Churchill operated the modernization of the Royal Navy from 1911 . During the First World War , he had to resign in 1915 because of the defeat he was accused of at Gallipoli . David Lloyd George brought him back to the war cabinet in 1916. In 1924 Churchill switched back to the Conservatives, who made him Chancellor of the Exchequer (1924–1929).

During the 1930s, in which Churchill's political career seemed to be over, he was primarily active as a publicist and writer. As one of the few politicians he warned the government, parliament and the public against the aggressive, revisionist politics of Nazi Germany , but was hardly heard.

Only when the Second World War broke out in 1939 did Adolf Hitler's declared opponent again receive a government office, initially again that of First Lord of the Admiralty. When Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain had to resign as a result of the hapless Allied warfare , Winston Churchill took over the office of head of government on May 10, 1940. With his refusal to enter into negotiations with Hitler and his speeches in the critical months of spring and summer 1940, he strengthened the will to resist and the readiness of the British to continue the war against National Socialist Germany . In terms of foreign policy, he played a decisive role in the creation of the anti-Hitler coalition between Great Britain, the USA and the Soviet Union , which ultimately won the victory over Germany and Japan . Despite this military triumph, he lost the general election in 1945 .

After the end of the war, Winston Churchill became a pioneer of European unification . Re-elected Prime Minister in 1951, he resigned after suffering a stroke in 1955. He represented his constituency of Woodford in north-east London in the House of Commons until 1964, a year before his death.

Life

Origin, school, military

Winston Churchill was born in Blenheim Palace , the castle of his grandfather John Spencer-Churchill, 7th Duke of Marlborough . His parents were the British politician Lord Randolph Churchill and the American millionaire daughter Jennie Jerome . The father was one of the founders of the modern Conservative Party , was its chairman, held various ministerial offices and was at times considered a promising candidate for the office of prime minister.

Churchill's paternal grandfather was a member of the British aristocracy as the Duke of Marlborough . As usual for the British hereditary nobility , only the Duke's eldest son inherited this title, but not his younger brother, Churchill's father Randolph. As his son, in turn, Winston Churchill was considered a commoner. In the 1950s he rejected the hereditary peer dignity , but he was accepted as a Knight Companion in the Order of the Garter in 1953 and thus elevated to the non-hereditary lower nobility as "Sir Winston Churchill". His origins from the British aristocracy secured him admission to renowned boarding schools and a career as an army officer in his youth , although his achievements as a student were rather poor.

From 1881 to 1892 Churchill attended elite schools at Ascot , Brighton and Harrow . The authoritarian educational system there resisted him, and he stayed seated several times. After leaving school, he applied to the military , but failed the entrance exam twice. In 1893 he came to Sandhurst as a cadet and at the age of 21 as a cavalry lieutenant in the 4th Hussar Regiment. At the military academy and in the army, Churchill felt in the right place for the first time. Without any pressure from school, he now acquired a profound literary education and shortly afterwards began to write himself. Until the end of his life, he was to cultivate a polished style as a journalist and book author, which earned him the Nobel Prize for literature . In his 1930 autobiography, Churchill described horse riding as his greatest delight in Sandhurst. Exercising has always been part of his life, and there is no evidence for the recommendation “ No Sports ” ascribed to him .

Between 1895 and 1901, Churchill took part as an active soldier and war correspondent in five different colonial wars , including in Cuba on the side of the Spanish during the war of independence there and in various parts of the Empire , such as in Malakand in the north-western frontier province of British India . In 1898 he volunteered as a lieutenant in the campaign to suppress the Mahdi uprising in Sudan . He rode one of the last great cavalry attacks in British military history at the Battle of Omdurman . He wrote the book The River War about this campaign . An Historical Account of the Reconquest of the Sudan .

He experienced the Second Boer War as a war correspondent for the Morning Post . According to his biographer Martin Gilbert , the contract that Churchill negotiated with the newspaper was "probably the cheapest contract any war correspondent had ever made". In addition, it "generally led to [...] improving the pay of journalists". After Churchill was captured in a railway attack by the Boers , he managed a spectacular escape from Pretoria to Delagoa Bay, almost 500 kilometers away in the Portuguese colony of Mozambique . Two books about his South African adventures, his war reports and his adventurous escape made him known and in the eyes of many compatriots a national hero. This benefited him in the general election of 1900.

Political rise

As early as 1899, Churchill had tried in vain for a seat in the British House of Commons in a by-election . After his return from the Boer War, he ran successfully in the general election of 1900 and entered parliament in March 1901 as a newly elected Conservative for the constituency of Oldham .

He made his first significant appearance in parliament on May 31, 1904 with the demonstrative conversion from the Conservatives to the Liberals . The reason he gave for this was that he shared the position of the liberals who advocated free trade on the question of “ free trade or protective tariffs ”. Since Churchill showed no great interest in economic issues either then or later, his biographer Sebastian Haffner suspects that the real motive for the change of party was the desire to escape years of backbenchering with the conservatives. With the Liberals, on the other hand, the mission-conscious young MP was immediately able to play an important role because of his spectacular transition. Most conservatives hated him after taking this step. Many contemporaries testify to this in their memoirs, such as Violet Bonham Carter or Eduard von der Heydt . Contemporary evidence is also the headline "Winston Churchill is out, OUT, OUT!" With which the conservative daily The Daily Telegraph celebrated Churchill's defeat by William Joynson-Hicks in a by-election in Manchester in 1908 . Nevertheless, Churchill never completely severed ties with his old party and maintained contacts with influential conservatives. Arthur Balfour remained benevolent to him on the whole, Hugh Cecil was his best man in 1908, and the young FE Smith , with whom Churchill founded a political club, The Other Club , became his closest personal friend at the time.

In the Liberal Party, Churchill moved further and further left on the political scale. He belonged to the social reformist wing of the party, and like his supporter David Lloyd George , he was soon seen by the public as a reckless but also admired radical. His ambition to become prime minister was shown early on. In 1907, for example, he confidently stated that he would be head of government at the time of his 43rd birthday. He assumed political responsibility early on as Undersecretary of State for the Colonies (1905–1908) under Lord Elgin and as Minister of Commerce (1908–1910) and Home Secretary (1910–1911). In particular because of his poor-friendly social policy, he met with strong rejection from the Tories. Scandalous because of his position inappropriateness, they judged his personal intervention in a shootout between the London police and anarchists known as the Siege of Sidney Street . The mistrust of many workers aroused in November 1910 the decision of Interior Minister Churchill to send soldiers to South Wales to calm the situation after the suppressed Tonypandy uprising . This political mortgage would weigh on him for decades.

During the Anglo-German Naval conflict came to a head, Prime Minister made Herbert Henry Asquith , Churchill in 1911 as successor to Reginald McKenna to the First Lord of the Admiralty ( Navy Minister ). His most important decision in this office before the beginning of World War I was to convert the British navy from coal to oil , which significantly increased its range of action.

Starting a family

According to the conventions of the time, a politician like Churchill needed a wife in order to continue his career. Two women whom he proposed to marry refused. The American actress Ethel Barrymore justified this with the fact that she was not up to the stressful life of a politician. In 1906, when Churchill was the Undersecretary of State in charge of the colonies, he met Clementine Hozier , ten years his junior . Both met again in 1908 and deepened the relationship. Churchill was now Minister of Commerce, the second most important economic office in the British government after the Chancellor of the Exchequer. They were married on September 12, 1908 at St Margaret's Church in Westminster .

The marriage resulted in four daughters and one son:

- Diana (born July 11, 1909 - † October 20, 1963)

- Randolph (May 28, 1911 - June 6, 1968)

- Sarah (7 October 1914 - 24 September 1982)

- Marigold (born November 15, 1918 - † August 23, 1921)

- Mary (September 15, 1922 - May 31, 2014)

First World War

As a cabinet member, Churchill played a key role in determining Britain's policy and strategy during World War I - first as First Lord of the Admiralty , and later, after his temporary resignation from the government, as Minister of Munitions .

At the Ministry of the Navy

Churchill sometimes exceeded his powers as First Lord of the Admiralty considerably, for example when he interfered in the operations of the British expeditionary forces in Belgium in the late summer of 1914 and tried to organize the defense of Antwerp on his own . As part of the naval war , he sent a strong fleet to the South Atlantic in October 1914, which tracked down the German East Asia Squadron of the Imperial Navy under Vice Admiral Graf Spee in the South Atlantic and destroyed it in a naval battle near the Falkland Islands .

Initiated by Churchill, from his Royal Navy support landing operations British, French, Indian , and especially Australian and New Zealand troops at Gallipoli and at Cape Helles on the Turkish peninsula Gelibolu at the south exit of the Dardanelles in late winter 1915 proved to be serious failures. The aim of the operation was to attack the Central Powers Germany and Austria-Hungary in the south via the Ottoman Empire allied with them . This was considered the " sick man on the Bosporus " and represented the weakest point of the opposing alliance. After initial successes, however, the Allied troops failed to break out of the two landing bridgeheads. In addition, Bulgaria entered the war on the side of the Central Powers, so that the prospect of a quick decision in the Balkans deteriorated significantly. Churchill's fleet chief John Fisher , who had criticized his plans from the start, then resigned.

Leaving and rejoining the government

In order to avert a crisis of confidence in the warfare of the Asquith government, the entry of the Conservatives into the cabinet became inevitable. Under their party leader Andrew Bonar Law , however, they tied the condition that Churchill, who was responsible for the looming defeat at the Dardanelles, had to resign as Minister of the Navy. Another reason for this demand was that Churchill had been considered a "traitor" by the Conservatives since he changed party. On May 18, 1915, he resigned as First Lord of the Admiralty. The withdrawal of troops from the Dardanelles lasted from December 19, 1915 to January 9, 1916. In the fighting, the Entente lost over 140,000 dead, wounded, missing and prisoners, while the Central Powers lost over 210,000 men.

Churchill remained from May 23 to November 16, 1915 in the insignificant position of Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster in the expanded Asquith government . But since he could no longer exert any significant influence on government work, he finally volunteered for the army and went to the front in Flanders and northern France. From November 20, 1915, he first served as a major in the 2nd Battalion of the Grenadier Guards . From January 1 to May 6, 1916, he commanded the 6th Battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers , now promoted to Lieutenant Colonel.

Churchill continued to exercise his parliamentary mandate during his military service. In March 1916, in a speech in front of the House of Commons, barely veiled, he demanded his reappointment as Minister of the Navy, but this only earned ridicule. It was not until David Lloyd George , who replaced Asquith as Prime Minister in December 1916, that Churchill, in defiance of the Conservatives, was reinstated as Minister of Munitions on July 16, 1917.

Development of modern weapon systems

As early as the end of 1914, Churchill, as Minister of the Navy alongside Maurice Hankey , Secretary of the Committee of Imperial Defense , advocated the construction of what were then known as the “land battleships”. The new armored weapon was supposed to set the frozen fronts in motion again. The Landships Committee was set up under Churchill's aegis . From the beginning of 1915 this drove the development of the tanks, which were to play a decisive role in the final phase of the war. After the war, a royal review board charged with determining responsibility for groundbreaking military innovations and major wartime strategic initiatives stated that the ability to dispose of the tanks was largely thanks to Churchill:

"The Commission has a need to explain that it is primarily thanks to the open-mindedness, courage and energy of the Very Honorable Winston Spencer Churchill that the nebulous idea of using armored vehicles for combat purposes has been realized."

Churchill was also among the first to fully appreciate the military potential of airplanes . It was clear to him that the machines, which had been used primarily for reconnaissance purposes and in individual battles during the World War, would revolutionize warfare . In the future, they could be used to carry attacks directly into the enemy's hinterland in order to hit the enemy’s military and industrial resources. Great Britain, too, would no longer be able to rely on its island location. As aviation minister, he therefore promoted the establishment of an air force from 1919 , which was also used in Iraq in 1920 to drop bombs against insurgents.

Churchill was well aware of the dangers of modern war. In his work The Aftermath in 1928 he looked back on the First World War, took stock of the experiences of the past and thus already described the war of the future:

“Airways opened up in which death and horror could be carried far behind the actual front lines, so that women, children, old people and the sick, who were naturally spared in earlier wars, were also affected. […] Humanity has never been in this situation before. Without a perceptible increase in her virtues and without the benefit of wiser leadership, she has for the first time in her hands the tools that can infallibly seal her own annihilation. [...] People would do well to pause and think about their new responsibilities. Death stands ready, compliant, expectant, and eager to mow down the peoples en masse; ready for a call to irrevocably shatter all remnants of civilization to dust. "

Post and interwar period

In the post-war government

After the war, Churchill took over the offices of Secretary of State for the Colonies in Lloyd George's coalition cabinet .

From 1919 Minister of War, he advocated the intervention of the Western Allies in the Russian Civil War on the side of the White Army . In 1917, the German Reich leadership had Lenin travel to Russia from his exile in Switzerland in order to destabilize its government and force the country out of the war coalition. Therefore, from the spring of 1918, British and French troops supported the anti-Bolshevik forces from Arkhangelsk and Murmansk . As early as July 1919, however, the unsuccessful British troops withdrew from Russia. Churchill was of the opinion that Bolshevism had to "be strangled in the cradle", but could not assert himself with his efforts for a more extensive military engagement in his own party.

In October 1922, after a backbencher revolt , the Conservatives left the cabinet and Lloyd George announced his resignation. With him fell the last liberal prime minister of Great Britain. The Liberals lost the next election; Churchill himself was clearly defeated in his constituency in Dundee. After two years of political abstinence and twenty years after his first change of party, Churchill rejoined the Conservative Party in 1924 .

Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Conservative Cabinet

In November of that year he became Chancellor of the Exchequer , i.e. Minister of Finance and Economics, in the conservative government of the new Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin and remained so until his election in 1929. With his French counterpart Joseph Caillaux , he concluded a foundation agreement in 1926 on the war debts that the French government had joined the British government until 1918. His most important decision in this office, however, was the reintroduction of the gold standard , which he enforced in 1925. This conservative financial policy led to the overvaluation of the pound sterling and thus to the rise in the price of British goods, to a collapse in exports and ultimately to an increase in unemployment to around 20 percent. The dissatisfaction of the workers culminated in the great general strike of 1926 . Churchill called for the labor dispute, which lasted more than six months, to be brought to an end by force. He believed, “Either the country breaks the general strike or the general strike breaks the country.” That never happened, but in 1931, two years after Churchill was replaced as Chancellor of the Exchequer, the gold standard was abolished because of its devastating economic effects.

After the general election of 1929, the crisis-ridden Baldwin government was replaced by a Labor cabinet under Ramsay MacDonald . In the same year Churchill became Chancellor of the University of Bristol, but also kept his seat in parliament and initially remained a member of the shadow cabinet during the opposition period .

Withdrawal from the shadow cabinet

At the end of 1929 Churchill went on a lecture tour to America. As a result of the New York stock market crash in October, which he witnessed on the sidelines, he too lost a lot of money that he had invested in stocks. Only his income as a writer and an increased activity as a columnist saved him from the impending ruin. In the following year, Churchill fell out with the elected Prime Minister and head of the Conservatives because of his allegedly overly indulgent attitude towards the Indian independence movement. As a staunch imperialist , he was their avowed opponent and saw their leader Mahatma Gandhi only as a “half-naked fakir”. In 1935 he explicitly called on the Indian princes to oppose the Government of India Act , and they refused by a large majority to join the federation provided for by the law. Some biographers therefore blame Churchill for the fact that a constructive integration of the pro-British Indian princely states into the self-government of India was prevented. Even more serious is the accusation that Churchill's government reacted indifferently to the famine in Bengal during the Second World War and thus accepted the deaths of around 3 million people.

In January 1931, Churchill resigned from Baldwin's shadow cabinet over disagreements over India. In December of the same year, he was hit by a taxi in New York. The injuries forced him to take a year of recovery, most of which he spent while traveling. So in 1932 he took a trip through Germany to research the planned biography of his ancestor Marlborough . The journey to the battlefields of the War of the Spanish Succession also took him to Munich . In his hotel there he met Ernst Hanfstaengl , then foreign press chief of the NSDAP , who agreed to arrange a meeting between him and Hitler. The meeting that had already been arranged was canceled at short notice after Churchill had asked critical questions about Hitler's anti-Semitism . The later opponents of the war never met personally.

Due to his frequent absence from Westminster, Churchill increasingly lost influence in the party-internal dispute over the direction of the party in the early 1930s. In contrast to the beginning of his political career, he was almost a reactionary at the time . Like most conservative politicians of the time, he initially underestimated Adolf Hitler and believed that he could see positive approaches in his and in Mussolini's politics. In some points there was even a certain degree of agreement. Churchill, for example, advocated eugenics as he saw in “the mentally weak” and “crazy” a threat to the prosperity, vitality and strength of British society. He advocated their segregation and sterilization so that the "curse dies with these people and is not passed on to future generations".

Churchill's attitude towards fascism changed when he realized that Hitler's policy was tantamount to a new war. His warnings and the sharp rejection of the policy of appeasement, the appeasement and indulgence towards the aggression of National Socialist Germany earned him the reputation of a warmonger in large parts of the British population . While he had tried in vain to talk to Hitler during his stay in Munich, he now rejected attempts by the German Reich government, including two invitations from Hitler to Berchtesgaden. In the long term, with this stance, he improved his relationship with some of his domestic political opponents, the anti-fascist left socialists and the Labor Party, but the vast majority of the British public in the 1930s saw Churchill as a man who had his future behind him. In the conservative parliamentary group, his support was limited to two MPs, which were still very insignificant at the time: Harold Macmillan and Brendan Bracken .

Activity as a painter and writer

He retired to his country estate Chartwell in Kent , where he devoted himself to his hobby, painting, but above all to his journalistic and writing work. In late 1933 he published his Marlborough biography, and in 1937 he began his four-volume History of the English-Speaking Peoples , which he was not able to complete until 20 years later, after his final resignation as Prime Minister. His journalistic activity was so extensive that he employed his own researchers and typists to whom he dictated his work until late at night. According to his biographer, William Raymond Manchester , Churchill was the highest paid writer and columnist in the world in the 1930s.

Churchill discovered painting as early as 1915, shortly after he left the government, thanks to his sister-in-law Gwendeline. He later trained his technique with the help of John Lavery and John Nicholson and kept the hobby for almost the rest of his life. He signed his pictures, which were mostly made in Chartwell, with "WSC" or "WSC". They prefer to show landscape and architectural motifs and were mostly in their possession until the death of Churchill's youngest daughter Mary Soames. The most important work in this collection is the oil painting The Goldfish Pool at Chartwell (1932), which was shown in the summer exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1948 . In 2021 the painting Tower of the Koutoubia Mosque (1943) achieved auction proceeds of 9.5 million euros at Christie's .

In these Wilderness Years - the years in the wilderness, as he later referred to the time of his inner exile - Churchill did not only pursue his artistic ambitions. He continued to maintain close political and social contacts in order to keep up with the developments of his time. Guests at his famous Chartwell dinners included: Heinrich Brüning , Frederick Lindemann and Charlie Chaplin .

Return to government

The warnings about Hitler were not taken seriously until his own policies made it clear to the British people and the British political class how justified Churchill's distrust had been. In March 1938, National Socialist Germany initially forced the "Anschluss" of Austria . In September it triggered the Sudeten crisis , which led to the Munich Agreement and the forced cession of the Sudetenland from the Czecho-Slovak Republic . Less than six months later, Hitler broke this agreement again: In March 1939, the Nazi propaganda euphemistically called the " smashing of the rest of Czech Republic " and the establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia . And finally, on March 21st, just six days after the Wehrmacht occupied Prague , Hitler extorted the cession of the Memelland from Lithuania under threat of war . Thus the appeasement policy had failed for everyone to see. On March 31, 1939, Great Britain and France felt compelled to issue a guarantee in favor of the Polish Republic .

Churchill, who had predicted this development, was now increasingly heard. Two days after the German invasion of Poland , which started World War II on September 1, 1939 , Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain appointed him to his war cabinet . As in 1911, on September 3, Churchill took over the post of First Lord of the Admiralty , d. H. of the Minister of the Navy. The declaration of war on the German Reich followed on the same day, but the great powers avoided direct confrontation on a large scale for another six months, so that Hitler and Stalin decided, as in the secret additional protocol of the German-Soviet non-aggression pact of August 24, 1939, that were able to divide up Polish territory unhindered. The following months up to the spring of 1940 went down in history as the " Sitzkrieg " ( French Drôle de guerre - "strange, strange war"; English Phoney War ).

Churchill knew the importance of iron ore deliveries from the Kiruna mine in Sweden via the ice-free Norwegian port of Narvik to the German Empire. From December 1939 he therefore urged the laying of sea mines on the shipping route along the coast of neutral Norway . This Operation Wilfred had German ore carrier, forced to escape into international waters where they then by the Royal Navy could have been sunk. Another plan was to lay drift mines in the Rhine on the Franco-German border as part of Operation Royal Marine . However, both plans were blocked by the French government until April 1940 so as not to provoke a German attack. In addition, Operation Wilfred would have hindered British-French arms deliveries to Finland in the winter war against the Soviet Union. It was not until May 1940 that several thousand drifting mines were laid in the Rhine, Moselle and Maas , which hindered shipping between Karlsruhe and Mainz .

As an alternative to these projects, Churchill favored Plan R 4 , the occupation of the Norwegian ports by British troops. However, the Germans got ahead of this plan by a few hours. In the utmost secrecy, they had prepared the Weser Exercise operation , which began on April 7, 1940 and led to the occupation of the first targets in Denmark and Norway on April 9 . The Royal Navy could therefore no longer reach Narvik without a fight. In the ensuing battle for Narvik , the inexperienced Anglo-French expeditionary force , which had been reinforced by Norwegian troops on April 24, almost defeated the German mountain troops. Ultimately, the Allied operation failed due to a lack of supplies and after the start of the German campaign in the west on May 10, 1940, the last British-French units withdrew from Norway.

The war premiere

The British and French could not prevent the German occupation of Poland and Denmark or the attack on Norway. With the failure of Plan R 4 , Premier Chamberlain lost the last political support in the population and parliament . After the so-called Norway debate, the former advocate of the appeasement policy was forced to resign.

Although Churchill was blamed by parts of the press for the failure in Norway, only he or Lord Halifax came into question as Chamberlain's successors . The latter enjoyed far more support from the Conservatives than Churchill, but as an appeasement politician was largely discredited by the opposition. The Labor Party made its entry into an all-party government dependent on Churchill taking over its leadership. On May 9th, Chamberlain announced his resignation. On May 10, Winston Churchill headed a government of the National Coalition . His wartime government brought together Conservatives, Labor and Liberals. In addition to the office of prime minister, he himself also took on that of defense minister. On the day the government was formed, the German campaign in the west began with the attack on Luxembourg , Belgium and the Netherlands . From May 24th, the Allied troops were relocated from Norway to France. On June 8th, Narvik fell into German hands, and with the invasion of France by the Wehrmacht , the decisive second phase of the western offensive began .

Spring and Summer 1940

Due to the unexpectedly rapid advance of the Wehrmacht in the western campaign , Churchill was confronted with the complete failure of the Allied war strategy in the first days of his tenure. On May 21, German tank units reached the Channel coast at Abbeville , so that the British expeditionary corps was enclosed at Dunkerque . When France's military defeat became apparent in the first weeks of June, Churchill tried to prevent the ally from surrendering at all costs. For this reason he proposed a Franco-British union to the French government , the unification of the two countries. The French fleet and the French troops stationed outside Europe would have remained at the disposal of the joint high command. In France, however, the proponents of surrender prevailed, which formed a new government under Marshal Philippe Pétain . The latter signed an armistice with Germany on June 22nd in Compiègne . France left the war.

Most historians agree that Hitler has never come close to a victory as in spring and summer 1940: The Soviet Union supported Germany, France was defeated, and Britain stood alone and without sufficient armored army the German war machine against the already half Europe overrun would have. In addition, some members of Churchill's cabinet continued to lean towards Chamberlain's policy of appeasement and advocated negotiations with the German Reich. As their protagonist, Foreign Minister Lord Halifax was still ready to replace Churchill as prime minister. The historian John Lukacs even sees the decisive turning point in the war against Hitler in the conflict with Halifax, which culminated in the last week of May 1940 . Churchill's war strategy prevented his victory and only later made that of the Allies possible.

In Churchill's own words, Hitler's victory would have meant that "the whole world, including the United States, including all that we have known and loved, must sink into the abyss of a new dark age." Therefore, in June, despite resistance in his own government, he demanded that no concessions should be made to Germany and that the war should be continued from overseas if necessary.

As early as May 13th, in his first speech as Prime Minister, Churchill had announced to his compatriots “ nothing but blood, hardship, tears and sweat ” and stated that the “war against a monstrous tyranny as it has never been surpassed in the sinister catalog the crimes of humanity ”, can only be ended with a“ victory at any price ”. Even after the defeat of France, when many gave up the war for England, Churchill insisted on goals which, practically at that time, amounted to the unconditional surrender of Germany. On June 18, he said in front of the House of Commons:

“What we ask is fair and we take nothing back. We don't let go of an iota or an i-dot. Czechs and Poles, Norwegians, Dutch and Belgians have united their cause with ours. They all have to be raised up again. "

With another speech ( We Shall Fight on the Beaches ) he agreed on June 4, Parliament and a little later in a radio address the British people to the resistance against Hitler's Germany. He made it unmistakably clear - also addressed to his address:

“We'll go to the end. We will fight in France, we will fight on the seas and oceans. We will fight in the air with increasing confidence and increasing strength. We will defend our island, whatever the price. We will fight on the beaches, we will fight in the landing sites, we will fight in the fields and on the streets, we will fight in the hills. We will never surrender. "

As a result of this uncompromising stance, Churchill also ignored Hitler's so-called "peace offer" to Great Britain in the Reichstag speech of July 19, 1940. Until then, the German leadership had hoped that, in view of the war situation, British politicians who were more willing to compromise could replace Churchill Destroyed July 22nd. Churchill prompted Lord Halifax, of all people, who was known as a former advocate of appeasement, to respond to Hitler's speech: "Germany will maintain peace when it has vacated the territories it occupied, restored all the freedoms it had suppressed and given guarantees for the future."

Risk of invasion and aerial warfare

Churchill successfully passed his first major challenges in office: his government succeeded in withdrawing most of the defeated British expeditionary corps from Dunkirk and prevented a German invasion . The prime minister laid the foundations for this immediately after he entered government by giving aircraft production top priority and giving Lord Beaverbrook responsibility for it. When the Battle of Britain reached its climax in August 1940, it was largely thanks to his achievements and those of Air Marshal Hugh Dowding that the Royal Air Force (RAF) was able to wrest a military stalemate from the German Air Force. For the first time, Hitler failed to impose his will on a country. Churchill's decision to continue fighting, which had finally fallen in the days of Dunkirk, finally forced Hitler to venture into the war against the Soviet Union, which had been planned from the beginning, without having ended the war in the West. Historians like Ian Kershaw see this as the beginning of the end of Hitler's war strategy.

Churchill's order to sink the bulk of the French Mediterranean fleet also served to ward off a German invasion . Because after the armistice, the government of Marshal Pétain in Vichy pursued a policy of collaboration with Germany: The navy of the previous ally threatened to fall into Hitler's hands. In a preventive action, Operation Catapult , the Royal Navy therefore destroyed several French battleships and destroyers anchored off the Algerian port of Mers-el-Kébir on July 3, 1940 . 1267 French marines died in the process. The Vichy regime then broke off diplomatic relations with Great Britain. Another reason for this may have been that Churchill had enabled the Brigadier General and State Secretary in the French War Ministry Charles de Gaulle on June 18, 1940 to send his famous appeal to his compatriots via the BBC , in which he urged them to continue the fight. On August 8, Churchill and de Gaulle signed the Checkers Accords , in which Britain pledged to respect the integrity of all French possessions and the "integral restoration and independence and greatness of France". Despite strong personal reservations about de Gaulle, Churchill recognized him as the legitimate representative of Free France .

The German invasion plan (" Operation Sea Lion ") was repeatedly postponed in the autumn of 1940 until it was finally abandoned in the spring of 1941. During this time, German bombers constantly flew air raids on London and many other cities in England, which - such as Coventry - suffered severe damage. From August 25, 1940, on Churchill's orders, the Royal Air Force also started bombing residential areas in German cities, after air raids had already been carried out against industrial plants in the Ruhr area .

The British people saw the actions of the Royal Air Force as a legitimate answer to the German warfare, which had launched heavy air strikes on civilian targets for the first time in history with the bombings of Guernica , Warsaw , Rotterdam and the cities of southern England. On February 14, 1942, the Ministry of Aviation issued the Area Bombing Directive . It authorized Arthur Harris , the recently appointed new Commander-in-Chief of the British Bomber Command , to carry out area bombings that were intended to break the enemy's morale .

By mid-1944 at the latest, when the British and Americans had achieved unrestricted control of the air over the Reich, these area bombings had a momentum of their own that even Churchill could not or would not stop. During this time, numerous German cities were reduced to rubble and ashes. It was only the high number of victims in the air raids on Dresden that prompted Churchill to question the bombing of German cities without, however, abandoning the line previously taken. At the very end of the war, he distanced himself from Air Marshal Harris, who was one of the advocates of moral bombing and had always understood this to be a mandate of his government.

The big three

As long as Great Britain stood alone in the fight against Nazi Germany, Churchill could only ensure that Great Britain did not lose the war. However, he was aware that a victory was only possible in an alliance with the United States . He therefore relied on a good relationship with Franklin D. Roosevelt . The US president but could before his re-election in November 1940 not dare to embroil his country directly to war.

Nevertheless, Churchill achieved that Great Britain was supplied with vital and war-essential goods from the USA via the North Atlantic. The Lending Act that Roosevelt brought through Congress on March 11, 1941 , was a direct initiative of Churchill in May 1940. It allowed the US government, among other things, to lend warships to Great Britain.

On August 14, 1941, Roosevelt and Churchill met off Newfoundland on the battleship HMS Prince of Wales . There they signed the Atlantic Charter , which, with its “Eight Freedoms”, was to become the basis of the post-war order and the United Nations .

By then, Britain's situation had already improved significantly. Hitler's attacks on the Balkans and North Africa had already reduced the number of German air raids on targets in Great Britain. After the attack by the Wehrmacht on the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, the United Kingdom was no longer alone in the war. Although he mistrusted Josef Stalin because of his pact with Hitler , Churchill immediately offered him support. In spite of the precarious situation in which Great Britain found itself, British and US relief supplies were delivered to the Soviet Union from October 1941 onwards.

On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor , and on December 11, Hitler declared war on the US. Churchill finally had the ally he wanted by his side. Among the "Big Three" - Roosevelt, Stalin and Churchill - in the end he would only be left with the role of the Americans' junior partner. Nevertheless, he continued to exert a great influence on the conduct of the war, now with a view to the time after Hitler's defeat. Because he recognized more clearly than Roosevelt the danger that a Soviet-dominated Europe could follow the Nazi-ruled Europe.

Churchill's Mediterranean plan was an expression of this fear. As in the Battle of Gallipoli in World War I, he wanted to attack the enemies at their weakest point in the south - this time in Italy - then bypass the Alps to the east, advance into Austria and central Germany and at the same time cut off the German troops in the Balkans. With this he wanted to preserve the chance to decide the war before the advance of the Red Army far into Central Europe . A first step towards this plan was Operation Torch , the landing of the British and Americans in North Africa on November 8, 1942.

At the Casablanca Conference from January 14 to 26, 1943, Churchill and Roosevelt laid down the common war strategy. They agreed on the principle of Germany first , according to which the overthrow of Hitler's Germany should take precedence over the war against Japan. Against Churchill's reservations, who did not consider this to be psychologically wise, Roosevelt pushed through the demand for the unconditional surrender of Germany.

On July 10, 1943, the Italian campaign began with the landing of British and American troops in Sicily . On July 25th, Mussolini was overthrown . But the Allied invasion of Italy across the Apennine Peninsula was progressing much more slowly than Churchill had hoped. At the Tehran Conference from November 28 to December 1, 1943, he and Roosevelt met Stalin for the first time: The latter was now pushing for the opening of a second front in France. The so-called westward shift of Poland was also decided: After the end of the war, the Soviet Union was to keep the eastern Polish territories that had already been won in the Hitler-Stalin Pact , for which Poland was to be compensated with eastern German territories. At the Potsdam Conference in 1945 they agreed on the Oder-Neisse line as the new Polish western border.

On the way to the Tehran Conference, Churchill stopped in Egypt . At the Cairo Conference on November 1, 1943, he discussed further military action against Japan in East Asia with Roosevelt and Chiang Kai-shek , the head of state of China . At the second Cairo conference on December 26th, Churchill persuaded Roosevelt that the allies would adhere to the principle of “Germany first”. According to this, the war efforts in the Pacific should only be accelerated in Europe after the end of the war.

On D-Day , June 6, 1944, Operation Neptune finally began the allied landing in Normandy , which Stalin had long called for, under the code name "Operation Overlord". In France the Allies made rapid progress and liberated Paris as early as August . In October their troops reached the imperial border near Aachen . Churchill met with Roosevelt in Québec, Canada from September 11 to 16, 1944, to discuss further cooperation between the Allies in Europe and the Pacific .

With his Foreign Minister, Anthony Eden , he visited Moscow from October 9th to 19th, 1944 . Despite the successes of the British and American troops, he continued to fear that the Red Army would advance faster and further into Central Europe than the Western Allies. Therefore, he agreed with Stalin to divide Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe into spheres of interest . Romania , Bulgaria and Hungary were assigned to the Soviet sphere of influence, Greece to the British. In Yugoslavia , both powers wanted to share their influence.

The German Wehrmacht's Ardennes offensive (December 16, 1944 to January 1945) heightened his concerns, so that at the Yalta Conference from February 4 to 11, 1945, he was ready to make further concessions to Stalin. There it was decided not only to divide Germany into four zones of occupation , but also to divide Europe into a western and a Soviet sphere of influence, as it existed until 1989 . Churchill had to deal not only with Stalin, but also with Roosevelt: The latter was much less suspicious of the Soviets and believed that after the war he could integrate them into a real peace order.

The war was now drawing to a close. In March, when the British troops were on the Rhine , Churchill paid his Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery , a visit and crossed the river with him at Wesel . On May 8, 1945, he was able to announce the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht and thus victory in Europe ( VE Day ) in front of the British House of Commons .

After Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945, Churchill met with his successor Harry S. Truman and with Stalin on July 17 at the Potsdam Conference to discuss how to proceed in Germany and against Japan, which was still fighting.

Again in the opposition

In the middle of the Potsdam Conference, Churchill was replaced as Prime Minister by his previous deputy Clement Attlee . The Labor Party won the general election of July 1945 because it promised the British better schools, better housing and a public health system. Churchill's election campaign program - the continuation of the war against Japan and the warning of a financial “Gestapo” - seemed to the voters, on the other hand, not very future-oriented.

For the next six years he was opposition leader in the lower house. As a globally respected statesman, he also used this time to draw attention to current opportunities and dangers. He was one of the first to recognize the consequences of Stalin's policy of violence during the war. In May 1945, for fear of the Red Army advancing further into Western Europe, he had commissioned the British General Staff to work out Operation Unthinkable , a secret plan for an attack on the Soviet Union . However, due to military and political considerations, the plan was dropped. Well, after the war, Churchill supported President Truman's policy of containment towards the Soviet Union and coined the term “ Iron Curtain ” (see below) for the border between Eastern and Western Europe. He also encouraged the USA to use its monopoly on atomic and hydrogen bombs , which existed until 1954, for offensive political goals directed against the Soviet Union.

On the other hand, his famous speeches to the academic youth in Zurich in 1946 and the Council of Europe in Strasbourg in 1949 were trend-setting: in them he proposed the creation of the “ United States of Europe ”, the “first step of which must be a partnership between France and Germany”. "There can be no resurgence of Europe without a spiritually great France and an spiritually great Germany", he said and went on to speak of the need to give the European family of nations "[...] a structure under which they can live in peace, security and freedom can. We have to create a kind of United States of Europe. Only in this way can hundreds of millions of working people regain simple joys and hopes that make life worth living. "

Enthusiastic about the ideas of the French Foreign Minister Aristide Briand , he first commented on this concept in 1930 in the Saturday Evening Post . Now he saw it as a pragmatic way to reduce the hatred between the European peoples and to pacify the continent. With this he connected the calculation of strengthening the political weight of the European states vis-à-vis the USA and the Soviet Union, which was reduced as a result of two world wars. According to his vision, Great Britain should not be involved in the new European structures to be created: “We have our own dreams. We are with Europe, but not from him. We are connected, but not included. ”Apparently he hoped that Great Britain, which at that time still had an extensive colonial empire, could remain on an equal footing with its Atlantic partner, the USA, through an independent course. The basic constant of his plans remained the idea of a federal union of nation states that should live together in freedom and prosperity.

Second term

With Churchill as the top candidate, the Conservatives won a narrow election in October 1951 because this time he had adopted the Labor Party's campaign themes and promised the British a continuation of the state housing program. Domestically, his second term at 10 Downing Street was largely unspectacular. In foreign and colonial policy, on the other hand, he had to deal with several sources of conflict inherited from the previous government. He did so as a staunch advocate of the British Empire and colonialism .

In the Abadan crisis, for example, Churchill demanded and supported the measures of the American secret service CIA , which ultimately led to the overthrow of the democratically elected Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh . The crisis arose when, at the instigation of Mossadegh, the Iranian parliament decided in early 1951 to nationalize the country's oil industry , which was under British control.

A rebellion against British rule had broken out in Malaya as early as 1948. Unrest also smoldered in the colony of Kenya , which culminated in the Mau Mau War in 1952 . In both cases Churchill advocated putting down the uprisings militarily. But then he tried to find politically acceptable solutions for all sides. The peace talks he initiated with the insurgents in Kenya failed shortly after he left office. For the Malay sultanates in Malaya , now Malaysia , and for Singapore , he had plans for independence drawn up in 1953, which were implemented in 1957.

After Stalin's death on March 5, 1953, Churchill surprisingly offered the Soviet Union the dissolution of the blocs and the creation of a pan-European security system. Three months after Stalin, he himself suffered a repeated stroke that left him unable to work for a long time. Because his administration was permanently impaired, his party friends urged him to resign prematurely in 1955. Churchill resigned on April 5 of that year, and the Tory majority in the House of Commons elected Anthony Eden to succeed him.

Honors and last years

Queen Elizabeth II made Winston Churchill Knight of the Order of the Garter in 1953 . In the same year he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature - not only for his great Marlborough biography and his war memories, “ The Second World War ” , but in general “... for his mastery in historical and biographical presentation as well as for his brilliant eloquence in defense of the highest human values. ”Since he was still bedridden after the stroke, his wife Clementine accepted the award on his behalf.

Queen Churchill had given another special honor after his resignation from office. In 1955 she offered him the newly created title of Duke of London and thus the hereditary peer status. Churchill turned this down, however, in order to remain a member of the House of Commons, but also to enable his son Randolph to pursue a political career there. Because according to the legal situation at the time, Randolph Churchill would have inherited the title of Duke after the death of his father and then had to move to the House of Lords. The previously accepted admission to the Order of the Garter, however, was only connected with the personal nobility, which did not stand in the way of further membership in the House of Commons. Sir Winston, as he was allowed to call himself since 1953, was elected two more times in 1955 and 1959 to the House of Commons, to which he had been a member for more than 60 years. However, he no longer appeared as a speaker.

After his resignation, Churchill lived in seclusion for another ten years. In July 1959 he made a Mediterranean cruise with the shipowner Aristoteles Onassis and Maria Callas on his yacht Christina . He died at the age of 91 on January 24, 1965 - 70 years to the day after the death of his father. He was laid out in Westminster Hall for three days and then honored with a state ceremony in St Paul's Cathedral . 112 heads of state attended the funeral service. Churchill was buried in his family's grave in Saint Martin's Churchyard in Bladon, Oxfordshire, near his birthplace in Woodstock . The 50th anniversary of the burial was celebrated in 2015 as an official day of remembrance with church services.

personality

Churchill admired men like Napoleon and his own ancestors Marlborough and, according to several biographers, was convinced from his youth that he was also called to great things. According to Andrew Roberts , aristocratic origins gave him tremendous self-confidence. At the age of 16, for example, he told a friend that he would one day save Great Britain from an enemy invasion. As Roy Jenkins writes, Churchill said to his future confidante Violet Bonham Carter when they first met in 1906: “We are all just worms. But I think I'm a glowworm. ” Sebastian Haffner also states that Churchill believed in fate. Peter de Mendelssohn wrote of Churchill and David Lloyd George: “British politics has never more clearly shown than in these two men the two fundamental driving forces that inexorably push a man to the highest position in state and community, to power, authority and responsibility . Lloyd George saw a task and expected himself to be big enough to do it. Churchill saw himself and expected the task to be big enough for him. "

The widely spread claim that Churchill was an alcoholic is contradicted by his biographer Roy Jenkins. Churchill consumed tobacco and alcohol all his life, but was never dependent on them. Periodically, however, he suffered from depression , which increased with age.

Churchill as a publicist

As a young lieutenant in the 4th Queen's Own Hussars, Churchill improved his salary by publishing war reports in various British papers. Throughout his military and political career, journalism remained his main source of income. During his life he published more than 40 books and thousands of newspaper articles.

Churchill's first book, The Story of the Malakand Field Force , was published in 1898 and consisted of a collection of war reports. The following year he published his first monograph , The River War , which deals with the suppression of the Mahdi uprising . To relax Churchill wrote his only novel: Savrola appears in 1900 and describes the bloody revolution in a fictional European military dictatorship. In 1906 the two-volume biography of his father followed. From 1923 he published The World Crisis , a multi-volume story of the First World War. In addition to Lloyd George's memories of the war, this book significantly shaped the negative view of the British on what was happening on the Western Front in the post-war years.

After his preliminary retirement in 1929, Churchill intensified his writing activity. In 1930 My Early Life appeared , in which he described his youth and early years. It is his most personal work and is widely regarded as his best. From 1933 to 1938 he devoted himself to the publication of a large, four-volume biography of his ancestor Marlborough. In between he brought out Great Contemporaries , a collection of essays with portraits of important contemporaries such as John Morley , Herbert Asquith , George Nathaniel Curzon , Arthur Balfour and the Earl of Rosebery . After the Second World War he brought out his six-volume story The Second World War , for which he was honored with the Nobel Prize in 1953. From 1956 to 1958 his last major work followed: A History of the English-Speaking Peoples , a history of the English-speaking peoples, with which he had already started in 1937, however, after Sebastian Haffner, showed his limits as a historian.

Churchill in the judgment of contemporaries and posterity

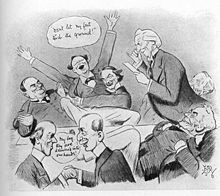

It portrays Churchill (hi., 2nd from left) as "Luftikus" among the cabinet members of the Asquith government and supports the verdict "brilliant but unsound" that was widespread about Churchill in the prewar period.

In his opponent, Hitler only wanted to discover “this talker and drunkard Churchill” who had prevented him from performing “great works of peace”. In contrast, a work published in Oxford in 1993 with contributions from 29 historians and politicians praised Churchill as “perhaps the greatest figure of the 20th century”.

His dazzling personality irritated his contemporaries and defies any one-dimensional assessment. Churchill embodied the radical social reformer in his political existence, but also the reactionary imperialist. On the one hand he was the much-vaunted warrior who, with his toughness and unscrupulousness, seemed to fit better into the 18th century Marlborough, on the other hand the politician who helped found the UN and the European Union , and with his idea of the " United States of Europe " showed the way into the 21st century.

Committed to no party, let alone any party doctrine, he changed political camps whenever it seemed necessary and opportune to him. He was therefore decried as unreliable and even feared by friends because of his ideas. Lloyd George described Churchill's mind as "a powerful machine, but [...] if the mechanism failed or went wrong, the consequences were devastating".

According to Sebastian Haffner , Churchill was regarded by the British public as "brilliant but unsound" until the Second World War. His contemporaries saw it as dubious and dangerous that Churchill had a tendency to personally put himself in risky situations, such as the siege of Sidney Street in 1911 or the Antwerp expedition in 1914. Far-reaching but ultimately failed projects of Churchill - such as the Dardanelles Plan and the intervention in post-revolutionary Russia - seemed to confirm their judgment. The writer HG Wells spoke for many when he compared the early Churchill to a "hard-to-treat little boy who deserves to be put on his knee." Wells is likely to have expressed British majority opinion decades later when, shortly before World War II, he revised his views on Churchill: “I dare say that we will stand by Churchill, who made so many mistakes that he never made any more can do more, and he is at least quite cunning. ”The image of Churchill changed in a very similar way in the work of the cartoonist David Low : If he mocked Churchill as a“ reactionary ”and“ political adventurer ”until the 1930s, he showed solidarity from May 1940 with the newly appointed war premiere in the cartoon All Behind You Winston . After defeating Hitler in 1945, Low paid his former favorite enemy his respect in the cartoon The Two Churchills as the "leader of humanity". Churchill made it easy for critics insofar as he could be extremely vain, always mindful of his impact and the grand entrance. But he was also able to fill a big role. So said General de Gaulle , who was not one of his best friends, "Churchill seemed to me (in June 1940) as a man who had grown the coarsest work - provided it was at the same level."

In his foreign policy , Churchill was, as he himself put it, guided by the principle of "global responsibility". Based on the experience of the First World War, he saw the western democracies - especially Great Britain and the USA - have a duty to prevent a similar catastrophe in the future. After 1918, he initially saw the Soviet Union as the main opponent of world peace , but from the mid-1930s onwards, increasingly and because of its expansive policy, it was Germany that was more dangerous. He fought his predecessor Chamberlain's policy of appeasement because it made the war he was supposed to avoid all the more likely. In order to defeat National Socialist Germany , he did not shrink from the war-related alliance with Stalin, which in his view was the lesser of two evils. But he saw his work as half done in 1945 and was one of the first to call for the Soviet expansion policy to be curbed.

Churchill is still blamed for the British air war against German cities and the civilian population . The German publicist Jörg Friedrich therefore called him a mass murderer. He criticizes the fact that residential areas were deliberately attacked as part of the so-called moral bombing , even towards the end of the war, when this no longer had any military significance. The historian Frederick Taylor , on the other hand, emphasizes that after the withdrawal of its land forces from the continent of Germany, Great Britain could only attack with the help of the Royal Air Force. Precise attacks on purely military and industrial targets were not technically possible, at least in the initial phase - especially during night attacks.

During the Second World War, Churchill was asked what one actually fights for. His answer: "If we stopped fighting, you would soon find out." In a nutshell, Willy Bretscher , editor-in-chief of the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, said: "Churchill saved Europe in the summer of 1940." Churchill's compatriot Alan Moorehead said that Churchill was due to this Performance as the "greatest Briton since Wellington ". British and German historians and biographers share this point of view today. Despite the deaths in the bombing war, for which the prime minister was partly responsible, according to Christian Graf von Krockow, "thanks to Churchill's inflexibility, millions and millions of people have been saved". Arnold J. Toynbee judged years after the war: “Without Churchill the world would be in chains today.” His Swedish biographer Knut Hagberg made a similar statement in 1945: “If Winston Churchill had not succeeded in waking England to battle, then it would soon there was no longer any free country in Europe. ”And Peter de Mendelssohn wrote:“ Others wanted to and had to face the future. He had caused there to be a present at all. "

These and many similar statements made by his contemporaries reveal what, even according to current research, counts as Churchill's historic life achievement: that he prevented Hitler's victory. In the seemingly hopeless situation of the summer of 1940, he convinced the British not to give up the war yet, strengthened their will to persevere and laid the foundations for the coming anti-Hitler coalition with the USA and the Soviet Union. For these reasons, many German Churchill biographers such as Hans-Peter Schwarz , Christian Graf von Krockow and Sebastian Haffner see Churchill, not Roosevelt or Stalin, as Hitler's decisive opponent. As John Lukacs put it: “Churchill and Britain could not have won World War II, America and Russia ended up doing so. In May 1940, Churchill was the one who didn't lose him . "

When Winston Churchill was born, the British Empire was at its zenith. By the time he died Britain had become a second-rate power. He himself may have found this a failure and a tragedy. But: “A feature of size cannot just be what someone creates in a significant way down here,” wrote his biographer Peter de Mendelssohn. “Rather, real greatness is also able to live in the foresight, the determination and the unshakable energy with which one stands in the way of the pernicious creation and is able to summon the forces, to gather together and to spur them on to the utmost performance, which block the road to disaster. One such was Winston Churchill. "

Awards, honors, memberships

- In 1901 Winston Churchill was transferred to the London Masonic Lodge “United Studholme Lodge No. 1591 "and in 1902 in the" Rosemary Lodge No. 2851 “raised to the title of master. However, according to the Grand Secretary of the Grand Lodge of England , Sir Sidney White, he was a rather passive member who did not attend the Lodge meetings for many years. In 1908 he joined the Albion Lodge of the Ancient Order of Druids .

- In addition, Churchill was a member of several renowned gentlemen's clubs : as a liberal in the Reform Club , as a conservative since 1924 in the Carlton and the Athenaeum Club .

- Since 1922 Churchill was the holder of the Order of the Companions of Honor .

- In 1924 he received the Territorial Decoration .

- In 1936 he became President of the British Section of the New Commonwealth Society .

- The Churchill heavy assault tank , built from 1940, was named after him.

- In 1941 Churchill received the honorary title of Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports and was accepted as a Fellow of the Royal Society .

- Churchill received the Order of Merit in 1946 and was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in the United States .

- In 1950 the University of Copenhagen awarded him the special Sonning Prize .

- In 1951 he became an elected member of the American Philosophical Society .

- In 1952 he became an Honorary Fellow of the British Academy .

- In 1953 Churchill was accepted into the Order of the Garter.

- In 1953 he received the Nobel Prize for Literature .

- In 1956 the city of Aachen awarded him the Charlemagne Prize for 1955 as "Guardian of human freedom - admonisher of European youth".

- In 1958 Churchill College , Cambridge, received his name.

- In 1963 Churchill was made the first honorary citizen of the United States .

- In 1965 the Canadian Churchill Falls got his name.

- In 1965, a commemorative coin with the face value of a crown bearing his portrait was issued in Great Britain .

- In 1965 the Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names named the Churchill Mountains after him.

- 1968–1970 the Royal Navy launched three Churchill-class nuclear-powered fighter submarines .

- In 1969 he was posthumously awarded the United States Congressional Gold Medal .

- In 1973 a bronze statue of Churchill was erected in London's Parliament Square, in front of the House of Commons.

- In 2001, the United States Navy commissioned the USS Winston S. Churchill (DDG-81) , the only active warship (as of 2019) to bear the name of a foreign citizen and only the fourth in US history to be named after a British was named.

- In 2002, Churchill was voted Greatest Briton of All Time in a telephone vote by the BBC . While the vote was not representative , 450,000 UK residents did vote .

- The Churchill Cup , a rugby tournament, has been held since 2003 .

Churchill in the film

Churchill's life has been the subject of hundreds of television documentaries, as well as television and cinema films. These include, for example:

- The Finest Hours by Peter Baylis (1964); Oscar nominated documentary

- The Young Lion by Richard Attenborough (1972); Feature film with Simon Ward about Churchill's beginnings as a politician

- Churchill - The Gathering Storm by Richard Loncraine (2002); Award-winning documentary television film with Albert Finney and Vanessa Redgrave about Churchill's years before the Second World War

- Winston Churchill: The Wilderness Years by Ferdinand Fairfax (2005); Television series

- Inglourious Basterds by Quentin Tarantino (2009); Feature film with Rod Taylor as Churchill

- Paradox - The Parallel World by Brenton Spencer (2010); Feature film with Alan C. Peterson as Churchill

- The King's Speech by Tom Hooper (2010); Feature film with Timothy Spall as Churchill

- The Crown (2016); Netflix series with John Lithgow as Churchill

- Peaky Blinders - Gangs of Birmingham ; BBC series with Andy Nyman as Churchill

- Churchill by Jonathan Teplitzky (2017); Feature film with Brian Cox as Churchill

- The darkest hour of Joe Wright (2017); Feature film with Gary Oldman as Churchill about his role at the beginning of the Second World War

- individual episodes of the British television series Doctor Who

Publications (selection)

- Ronald I. Cohen: Bibliography of the Writings of Sir Winston Churchill. Thoemmes Continuum, London 2006, 3 volumes, ISBN 0-8264-7235-4 .

- The Story of the Malakand Field Force. An episode of Frontier War. 1898.

- The River War. An Historical Account of the Reconquest of the Sudan. 1899 (German crusade against the realm of Mahdi , Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt 2008, Die Andere Bibliothek series , ISBN 978-3-8218-4765-8 ; Gutenberg project ).

- Savrola . 1900 (novel).

- From London to Ladysmith via Pretoria. 1900.

- Ian Hamilton's March. London 1900.

- Lord Randolph Churchill. 1906.

- My African Journey. 1908.

- The World Crisis. 4 volumes, 1923 to 1929.

- My early life . 1930 (German: My early years , List paperback no. 293/294, Paul List Verlag, 4th edition, Munich 1965).

- Marlborough. His Life and Times. 1933 to 1938, 4 volumes (German Marlborough , 2 volumes, Zurich 1990, Manesse Library of World History ).

- Great contemporaries. 1937 (German large contemporaries , Fischer Bücherei, Frankfurt / Hamburg 1959), collection of magazine essays, including about George B. Shaw , Alfons XIII. , George V , Georges Clemenceau , Wilhelm II , Lawrence of Arabia .

- The Second World War . 6 volumes, published 1948 to 1954, ISBN 3-502-19132-8 .

Translated into German:

- The second World War. With an epilogue about the post-war years. Translators and others Eduard Thorsch, abridged selection of the English work, Scherz Verlag 1985. Several paperback editions, e. B. Fischer Taschenbuch, 4th edition, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 978-3-596-16113-3 .

- A History of the English-Speaking Peoples . 1956 to 1958, 4 volumes (German history of the English-speaking peoples , 5 volumes, Augsburg 1990).

- Talking in times of war. Translated by Walther Weibel, selected, introduced and explained by Klaus Körner , Hamburg / Vienna 2002, ISBN 978-3-905811-93-3 .

- Notes on European history (= Knaur pocket books. Volume 177).

literature

- Peter Alter : Winston Churchill (1874-1965). Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-17-018786-4 .

- Peter Alter : The war premiere in peace. Winston Churchill 1945-1951. In: Michael Epkenhans , Ewald Frie (ed.): Politicians without office. From Metternich to Helmut Schmidt (= Otto von Bismarck Foundation Scientific Series, Volume 28). Schöningh, Paderborn 2020, ISBN 978-3-506-70264-7 , pp. 203-222.

- Robert Blake , Roger Louis (Eds.): Churchill. A Major New Assessment of His Life in Peace and War. Oxford 1993, ISBN 0-19-820317-9 (collection of articles by the most renowned contemporary Churchill experts).

- David Cannadine : Winston Churchill. Adventurer, monarchist, statesman. Berenberg, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-937834-05-2 .

- John Charmley : Churchill. The end of a legend. Ullstein, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-548-26502-2 .

- John Colville: Downing Street Diaries 1939-1945. Siedler, Berlin 1988, ISBN 3-88680-241-8 (diary entries of one of Churchill's closest collaborators during the war years).

- Virginia Cowles : Winston Churchill. The man and his time. Vienna 1954.

- Joachim Fest : Untimely hero of his time. Winston Churchill. In: Past repealed. Portraits and reflections. Munich 1983, pp. 215-238.

- Martin Gilbert , Randolph Churchill : Winston S. Churchill. 8 volumes with accompanying volumes. Thornton Butterworth, London 1966/1988, ISBN 0-434-13017-6 .

- Walter Graebner: Churchill - man. Rainer Wunderlich, Tübingen 1965 (English Original My dear Mr. Churchill. In: W. Graebner: Literary Trust. 1965).

- Sebastian Haffner : Winston Churchill. Kindler Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-463-40413-3 .

- Knut Hagberg : Winston Churchill. Stockholm 1945.

- Roy Jenkins : Churchill. Macmillan, London / Basingstoke / Oxford 2001, ISBN 0-333-78290-9 .

- John Keegan : Churchill. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 2002, ISBN 0-297-60776-6 .

- Thomas Kielinger : Winston Churchill. The late hero. A biography. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66889-0 .

- Christian Graf von Krockow : Churchill. A biography of the 20th century. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-455-11270-6 .

- Franz Lehnhoff: Winston Churchill. English and European. Cologne 1949.

- Elizabeth Longford : Winston Churchill. London 1974.

- John Lukacs : Five days in London. England and Germany in May 1940 . Siedler, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-88680-707-X (description of the decisive days in which Churchill enforced the continuation of the war against Germany in his cabinet).

- William Raymond Manchester : Winston Churchill. 2 volumes. Bertelsmann 1989/90.

- Peter de Mendelssohn : Churchill. His way and his world. Volume 1: Heritage and Adventure. Winston Churchill's youth 1874–1914. Lemm, Freiburg 1957.

- Alan Moorehead : Churchill. A picture biography. Kindler, Munich 1961.

- Robert Payne : The Great Man. A portrait of Winston Churchill. New York 1974.

- John Ramsden: Man of the Century. Winston Churchill and His Legend Since 1945. London 2003.

- Andrew Roberts : Churchill and his time. Dtv, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-423-24132-2 .

- Andrew Roberts: Churchill. Walking with Destiny. Allen Lane, London 2018, ISBN 978-0-241-20563-1 .

- David Stafford: Churchill & Secret Service. Abacus, London 1997, ISBN 0-349-11279-7 .

- Max Silberschmidt : Churchill - Leader of the free world In: Swiss monthly books: magazine for politics, economy, culture. 44, pp. 1-23 (1965).

Fiction

- Michael Köhlmeier : Two gentlemen on the beach. Hanser Verlag, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-446-24603-4 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Winston Churchill in the catalog of the German National Library (due to typing errors in the OPAC also search under: Churchill, Winston Spencer : the important work World Crisis in German, a total of 4 volumes, only 2 volumes listed here)

- Works by and about Winston Churchill in the German Digital Library

- Winston Churchill. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- The International Churchill Society

- Churchill and the Great Republic / Exhibition on Churchill Interactive exhibition of Library of Congress

- Newspaper article about Winston Churchill in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Mr Winston Churchill at Hansard (English)

Remarks

- ↑ The name Spencer is borrowed from the original family name of his ancestors on his father's side; he was given the first name Leonard in honor of his maternal grandfather, Leonard Jerome .

- ^ Winston Churchill: My Early Life. Thornton Butterworth, London 1930, p. 45.

- ↑ Christoph Drösser : Right? Sporty premier. In: The time . 25/2005, June 16, 2005.

- ↑ Winston S. Churchill: Crusade against the Empire of the Mahdi. (Original: The River War. A Historical Account of the Reconquest of the Sudan. London 1899.) Eichborn, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-8218-6204-0 , p. 7.

- ^ Martin Gilbert : Churchill. Volume 1, p. 451.

- ↑ The novel of a refugee . In: Düsseldorfer Volksblatt . Düsseldorf January 2, 1900, p. 2 ( zeitpunkt.nrw [PDF]).

- ↑ From London to Ladysmith via Pretoria and Ian Hamilton's March .

- ^ Roy Jenkins : Churchill. London 2001, p. 61 f.

- ^ Sebastian Haffner : Churchill. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg, 1985, pp. 44-46.

- ↑ Violet Bonham Carter: Winston Churchill as I Knew Him. London 1965.

- ↑ Eduard von der Heydt: On the Monte Verità. Memories and thoughts about people, art and politics. Zurich 1958.

- ^ Ronald Hyam: Elgin and Churchill at the Colonial Office. P. 357.

- ^ Martin Gilbert: Churchill. A life. Heinemann, London 1991, ISBN 0-434-29183-8 .

- ↑ Peter Alter: Winston Churchill (1874-1965). Life and survival. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 978-3-17-018786-3 , p. 75 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ↑ Walther Albrecht: Gunther Burstyn (1879-1945) and the development of the tank weapon. Biblio-Verlag, 1973, p. 35.

- ^ Alan Moorehead : Churchill. Munich 1960, p. 49 f.

- ↑ Winston Churchill: The World Crisis. Volume 4: The Aftermath (1918-1928). Thornton Butterworth, London 1929.

- ^ History of the University . University of Bristol, November 16, 2008.

- ^ Roy Jenkins: Churchill. Macmillan, London / Basingstoke / Oxford 2001, p. 427 ff.

- ↑ John Glendevon: The Viceroy at Bay . Collins, London 1971, ISBN 0-00-211476-3 , p. 20; In the original quote: "He and his friends must share much of the responsibility for the failure of the Princes to agree to Federation while there was still time to organize themselves effectively for the challenge of independence."

- ↑ Shashi Tharoor : The Ugly Briton. In: Time Magazine . November 29, 2010, Retrieved April 5, 2015 (Review of Madhusree Mukerjee 's book: Churchill's Secret War ).

- ↑ Nigel Knight: Churchill. The Greatest Briton Unmasked. David & Charles Publications, Cincinnati 2008, p. 55 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ Winston S. Churchill: The Second World War , Scherz Verlag, Bern / Munich / Vienna, new edition 1985, pp. 56-58.

- ↑ Virginia Cowles : Churchill. Vienna 1954.

- ^ Dietrich Aigner : The struggle for England. The German-British relationship. Public Opinion 1933–39. Munich 1969, p. 154 f.

- ↑ Winston Churchill: The Truth about Hitler. In: The Strand Magazine. November 1935, p. 10 f.

- ^ Martin Gilbert: Churchill and Eugenics. 2009.

- ↑ Klaus Larres : Churchill's Cold War. The Politics of Personal Diplomacy. New Haven 2002, p. 31 f.

- ↑ Peter Alter: Winston Churchill (1874-1965). Life and survival. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 978-3-17-018786-3 , p. 118 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ^ Dietrich Aigner: Winston Churchill. In: Rolf K. Hocevar (Ed.): The epoch of the world wars. Munich 1970.

- ^ William Manchester : Last Lion. Boston 1983.

- ^ Roy Jenkins: Churchill. Pan Books, London 2001, p. 279.

- ↑ Alexander Menden: Painting and walls. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung . December 17, 2014, p. 11.

- ↑ Anita Singh: Winston Churchill treasures to be sold at Sotheby's. In: The Telegraph. October 8, 2014.

- ↑ From the possession of Angelina Jolie - Churchill painting auctioned for 9.5 million euros. In: spiegel.de. March 2, 2021, accessed March 2, 2021 .

- ^ Operation Wilfred - Mining the Norwegian Leads, April 8, 1940. In: HistoryOfWar.org ( Mining the Norwegian coastal waters).

- ^ Operation Royal Marine - Mining the Rhine, May 1940. In: HistoryOfWar.org (British drifting mines in German inland waters).

- ↑ 1940 April. Württembergische Landesbibliothek Stuttgart (Allied superior power in Norway).

- ↑ 1940 April. Württembergische Landesbibliothek Stuttgart (Operation Wilfred April 5–8, 1940).