History of Styria

The history of Styria coincides with Austrian history in many epochs . This article is an overview of the region-specific peculiarities of the historical development up to today's state of Styria .

prehistory

The sparse oldest traces of the presence of humans in the area of today's Styria come from the Middle Paleolithic , the time of the Neanderthals . Essentially, there are finds of stone and bone tools in Graz Bergland in Repolust which Badlhöhle in Peggau and Drachenhöhle . Traces of Neolithic settlements have been found on the Pölshals and Buchkogel near Wildon , among others .

During the Bronze Age and Urnfield Age, an important cultural complex developed in Central Europe, which is attested to in Styria with finds in Wörschach , Königsberg near Tieschen , Bärnbach , Ringkogel near Hartberg , Kulm near Trofaiach and Kulm near Weiz .

The most important finds from the Hallstatt period are the princely grave on the Burgstallkogel in Kleinklein near Leibnitz and the cult car from Strettweg .

The immigration of the Celts into the area of today's Styria, which is assumed to have occurred between 450 and 250 BC, is decisive for the culture of the La Tène period . There are only a few individual finds of the La Tène culture from the 5th and 4th centuries. The focus of the grave finds from the Middle Latène period in Styria is in the 3rd century. The archaeological evidence suggests a Celtic population movement up the Mur . The largest part of today's Styrian area became part of the Kingdom of Noricum , whose administrative center was in the Klagenfurt Basin .

Roman times and the Great Migration

In the year 15 BC The Kingdom of Noricum became part of the Roman Empire . The conversion into a Roman province with the capital Virunum on the Zollfeld took place under Emperor Claudius . Under the rule of the Romans, during which the Celts, including the Noriker as the main tribe , continued to inhabit the country, the eastern part of today's Styria belonged to Pannonia , the western part to Noricum.

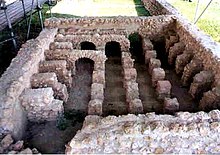

Around 70 AD, the town of Flavia Solva , which is located in the area surrounding today's town of Leibnitz , was granted town charter. The area of influence of this city extended to today's Upper Styria . In the 1st century AD, the Norican population was gradually Romanized . Around 170 the Marcomanni and Quadi broke into the province of Noricum and destroyed the city of Flavia Solva for the first time, which was rebuilt in the following years. During the administrative reform of the Roman Empire by Emperor Diocletian in 293, the province of Noricum was divided. Most of today's Styria belonged to the inland noricum (Noricum Mediterraneum), which extended in the north to the main Alpine ridge . The Ennstal and the surrounding areas belonged to Ufernoricum (Noricum ripense). At the end of the 4th century, Flavia Solva was completely destroyed a second time in the course of the German invasions and was never rebuilt.

The presence of Christians in Flavia Solva can only be proven by a bronze ring with a Christogram , an artifact that for a long time represented the only evidence of early Christians in Styria. But in recent years there has been added archaeological evidence such as that of an early Christian church on the Frauenberg near Leibnitz, and with a high degree of probability that of such a church on the Kugelstein near Frohnleiten .

During the Great Migration , Visigoths , Huns , Ostrogoths , Rugians and Longobards crossed or occupied the country one after the other. Nothing is known about the fate of the Roman-Noric population. Whether part of the Roman-Noric population has left the country for the south or west and whether part of the population has survived withdrawn in side valleys for the time being is controversial and a subject of speculation. In any case, the cultural and economic centers of the Romans fell into disrepair.

Carantania

Principality of Carantania

From 595 the ancestors of the Slovenes probably moved in via the Sava , Drava and Sann valleys into Inner Noricum, settled the area, partly beyond Inner Noricum, and founded the Principality of Carantania . Around 740, Borouth , Duke of Carantania, turned to Duke Odilo of Bavaria for help against the Avars . This was also granted, but against recognition of Bavarian or Franconian sovereignty.

From many toponyms of Slavic origin that still exist today (which, however, are not always immediately recognizable as such) in the south-eastern areas of Austria, one can easily understand the extent of the Slavic settlement.

The emergence of the polyethnic principality of the Carantans represents the oldest early medieval tribe formation that took place in the Eastern Alps from immigrants and locals. The Carantans were a clearly Slavic people who, however, had a non-Slavic name.

In the decades following the conquest, the Carantans were able to push back the influence of the Avars. After 741, the resurgent Avars tried again to subjugate the Carantans. They secured the help of Bavaria , fought back the attackers together, but the Karantanen came under Bavarian suzerainty.

As part of Carantania, the areas that later belonged to Styria also came under Bavarian rule from the middle of the 8th century and under Carolingian-Franconian rule from 788 .

Carantan mark

At the beginning of the 9th century, the Slavic princes of Carantania were replaced by Franconian border counts of Bavarian descent and the country was thus incorporated into the brand organization of the Franconian Empire .

After Charlemagne's victory over the Avars at the end of the 8th century, the Franconian Empire was expanded deep into the Pannonian region, as far as Lake Balaton, and a Carantan and a Pannonian province were established. Eastern Styria belonged to the latter .

Due to the incursion of the Magyars who appeared in Central Europe in the 9th century , all areas of the former Pannonia, i.e. the areas east of the Styrian peripheral mountains , were initially lost. With the victory of Otto the Great in the battle of the Lechfeld in 955, the advance of the Hungarians could be contained.

The borders of Bavaria, as part of the Holy Roman Empire founded by the Ottonians , were pushed forward to the east and brands were established as border counties, including the Karantanische Mark between the Koralpe and the Mur and to this in the south the Mark an der Drau and the Mark at the Sann .

Duchy of Carinthia (976–1180)

In 976 Carantania was separated from the Bavarian Duchy by Emperor Otto II, together with the brands Friuli , Istria , Carniola and the Karantanische Mark as well as the brand area on the Drau and Sann, and elevated to the Duchy of Carinthia .

Only under King Henry III. , in 1043, the borders of the Karantanische Mark against Hungary were permanently pushed up to the Lafnitz and Eastern Styria was incorporated into the Mark.

Manorial rule

With the beginning of the Franconian supremacy in Carantania, the basic rule common in the Franconian Empire was introduced in the Eastern Alpine countries, where it was to represent the decisive organizational form for the further settlement of these areas.

German settlement

The entire land had come to the Franconian king and subsequently to his successors, who now gave plenty of royal property to the church and its loyal followers, thus initiating the German settlement of the Eastern Alps. The landlords brought in German settlers, most of whom came from the old Bavarian regions, to make better use of their extensive and sparsely populated lands . A stronger immigration of German settlers into the area of today's Styria only came after the Battle of Lechfeld, i.e. after 955.

From the 10th century on, Germans and Slavs settled next to each other in Carantania without any strict language border separating them. In the Marken an der Drau and the Sann, the Slavic settlement was more dense than in the more northern areas, which, apart from a few cities, also resulted in fewer German settlers.

Spread of Christianity

The Christianity spread, starting from Salzburg, gradually in the areas of Carantanian. Salzburg was elevated to the status of a metropolitan seat and promoted the Christianization of the carantans.

Margraves of Traungau

In 1056 the Karantanische Mark Otakar von Steyr was awarded as the first margrave from the Traungau family , a relative of the Lambach family. The main castle of the Traungau was Steyr . So gradually the name Steiermark instead of Karantanermark became common. When the Dukes of Carinthia , the Eppensteiners , died out in 1122 , large areas of their allodial possessions , which were mainly in Upper Styria, fell to the Traungau people who were associated with them and they were able to consolidate their power. Under Margrave Otakar III. , who took over the market administration around 1139/40, the development of the sovereign principality began.

The high and noble free families of the country, who owned the most important and most fertile areas of land, were the greatest obstacle to the enforcement of sovereignty by the Traungau people. Otakar III. succeeded by force to get the center of the market, the Grazer Boden, where Graz , the final capital of the country, arose. He also inherited large estates in Lower Styria, which is now part of Slovenia, and which reached as far as the Save, and the Mark Pitten in present-day Lower Austria.

Church conditions

From an ecclesiastical point of view, the area of the Margraviate of Styria belonged to the Archdiocese of Salzburg , from where the impetus for the further expansion of the church structure came from.

A number of monasteries were also founded. The Göß Abbey was founded in 1020 by the Bavarian Count Palatine family of the Aribones . In 1074 Archbishop Gebhard von Salzburg founded the Admont Monastery . In 1096 the Eppenstein house monastery St. Lambrecht was founded . Further monasteries were founded: 1129 the Cistercian monastery Rein , 1140 the monastery Seckau , 1163 Vorau , 1164 Seiz ( Slovenian : Žiče) near Slovenske Konjice / Gonobitz in Lower Styria and 1164 Spital am Semmering .

Margraves of Styria from the Otakare family (Traungauer)

Otakare :

- Otakar or Ottokar I. (1056-1075)

- Adalbero , the rough (1075-1082)

- Otakar II (1082-1122)

- Leopold I , the Strong (1122–1129)

- Otakar III. (1129–1164)

- Otakar IV. (1163–1192), Duke from 1180

Duchy of Styria in the Middle Ages (1180–1500)

Babenberger

In 1180 Styria became a duchy and Margrave Otakar IV was made a duke by Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa . This process was closely related to the deposition of Henry the Lion and the reassignment of the Duchy of Bavaria. The new duchy was a fiefdom of the empire and thus Carinthia, Bavaria and Austria had equal rights. At the same time, all feudal ties to Bavaria expired.

Since Margrave Otakar IV was terminally ill with leprosy and had no male heirs, he concluded a succession treaty, the Georgenberg Handfeste , in 1186 with Leopold V of Austria from Babenberg, who was associated with the Traungau family . When he died in 1192, as the last of the Traungau residents, at the age of 29, Emperor Heinrich VI enfeoffed. on May 24, 1192 in Worms, Duke Leopold V of Austria and his son Friedrich with Styria. The connection between Austria and Styria was the first step towards the unification of the Eastern Alps. The Austrian Babenbergs took over a firmly established territory that was not made part of Austria , but initially retained sovereignty and practically became a subsidiary of the Duchy of Austria .

Leopold's sons Friedrich and Leopold VI. of Austria shared the 1194 rule over Austria and Styria, but came in 1198 with Frederick's death both in Leopold's hand. This was followed in 1230 by Leopold's only son, Friedrich the Arguable . Since he disregarded their rights, the Styrians brought a lawsuit with Emperor Friedrich II and received their freedoms contained in Otakar's will confirmed anew.

On the part of the regional princes, the desire for regional dioceses was increasingly brought to the church and in particular to the archdiocese of Salzburg. This had itself become an independent state principality. In order not to be exposed to opposition from other sovereigns and to avert greater political damage to the archbishopric, Archbishop Eberhard II set up several dioceses in his sphere of influence, including 1218 Seckau in Styria and 1225 Lavant in the Styrian-Carinthian border area. These bishoprics initially comprised only smaller areas and relatively few parishes. The bishops were appointed by the Archbishop of Salzburg. With the administration of his own diocese of Seckau, the bishop also took over the general vicariate of Salzburg for the duchy of Styria. This regulation was valid with minor deviations until the diocesan regulation in 1786.

Interregnum and beginning of the Habsburg rule

After the death of the last Babenberger, Frederick the Warrior in 1246, the unfavorable interregnum for Styria followed , in which the duchy, although a party of the estates elected Heinrich of Bavaria as duke in 1253, with the mediation of the Pope in the Peace of Ofen between the kings in 1254 Ottokar II. Přemysl of Bohemia and Bela IV. Of Hungary was divided. Ottokar II defeated the Hungarians in 1260 in the battle of Kressenbrunn on the Marchfeld . In the Peace of Vienna (1261) Styria went to Ottokar, in 1262 he was enfeoffed nominally with Austria and Styria by the German (counter) king Richard . To strengthen his power, he founded several cities and also initiated the rebuilding and fortification of Leoben and Bruck an der Mur . For military reasons, these cities were planned to be built around a large rectangular square. Under King Ottokar II, Bohemia, Moravia, Austria, Styria, Carinthia and Carniola were ruled by one ruler for the first time, but only for a short time. In 1276 the Styrian, Carinthian and Carniolan nobility rose up after the " pure oath " against King Ottokar and joined the party of Rudolf von Habsburg , who was elected Roman-German king in 1273 . At the same time Ottokar II was. Declared by King Rudolf von Habsburg his feud forfeited and 1278 in the Battle on the Marchfeld finally defeated, whereupon the latter in 1282 his sons Albrecht I and Rudolf II. With Austria, Styria, Carniola and the Windisch Mark belehnte . In 1283 Albrecht was installed as the sole hereditary sovereign of these countries. In 1292 he was able to successfully prevail against the aristocratic revolt of the Landsberger Bund . From then on, the Duchy of Styria (with a brief interruption, the rule of Matthias Corvinus over parts of the country from 1485 to 1490) remained in the possession of the House of Habsburg until 1918 .

In the 12th and 13th centuries, the immigration of German settlers increased, especially into the Graz Basin and the still less inhabited Eastern Styria (→ German East Settlement ). Land development by clearing the forests continued throughout the 13th century. As a result, the Slavic settlement islands of West and Upper Styria shrank more and more and finally disappeared in the 14th century as a result of the assimilation of the Slavic population. South from Radkersburg to the Drava , the area was settled according to plan by Slovenian colonists from the lower Marche. The terrible plague pandemic of the years 1348 to 1353 caused such a sharp decline in population that desertification and desertification occurred in its wake .

When after Rudolf IV's death in 1365 between his brothers Albrecht III. and Leopold III. The division made in the Treaty of Neuberg in 1379 fell to the latter with Carinthia, Tyrol and the neighboring countries. When his sons again divided the estate in 1406, Styria was awarded to Ernst the Iron , among others . It was the first of the two line divisions of the Habsburgs in their ancestral lands in the southeast of the empire . For the group of states administered from Graz, Styria, Carinthia, Krain, the county of Görz (from 1500), the city of Trieste and the Windische Mark, the designation Inner Austria became common. The eldest son and successor (since 1424) of Ernst the Iron was the future Emperor Friedrich III. , which in turn united all the Habsburg lands after the other lines had died out. Emperor Friedrich III. lived in various Austrian cities. He stayed in Graz the longest, namely 40 years. Among other things, he had the Graz Castle and the Graz Cathedral expanded in a late Gothic style. When the prince Counts of Cilli died out in 1456 , Friedrich acquired their properties on the basis of earlier contracts. In 1462 Styria was divided into quarters .

Mining, which was economically important for Upper Styria, grew stronger from the 12th century, especially salt mining in Bad Aussee , Hall and in the Halltal near Mariazell , iron mining on the Erzberg and in Johnsbach and silver mining in Oberzeiring and Schladming . The iron ore was smelted in the relatively primitive racing furnaces , but in later centuries it was smelted in the wheelworks , which are smelting furnaces in which the bellows was driven by water wheels. While many small entrepreneurs were initially active in iron production, the boiling of the salt in Aussee was taken over by the prince who ran the business with wage laborers as early as 1449. The salt springs near Admont were operated by the Admont Abbey, those in Halltal near Mariazell by the St. Lambrecht Abbey. The sovereign also intervened in the iron industry in the middle of the 15th century, although the trades remained independent for the time being.

In 1485 the plague picture was created on Graz Cathedral, which is noteworthy in terms of city history due to the oldest view of Graz. In addition, it clearly shows the heavy strains that the Styrian population was exposed to at that time: hunger, war and epidemics. Hunger caused by locust plagues - war not only triggered by the Turks, but also by the Hungarian invasions under King Matthias Corvinus and the uprising of the former imperial mercenary Andreas Baumkircher - recurring epidemics such as the plague in 1480.

From 1470 the Turks , who had conquered a large part of the Balkans , became a constant threat to Inner Austria. Again and again these countries were hit by Turkish invasions . They ravaged cities and destroyed farms, killed people, or dragged them into captivity. The son and successor of Frederick III, the Roman-German King and later Emperor Maximilian I , set up central administrative authorities in the hereditary lands. At the beginning of his government activities, he had Graz Castle expanded, with the stair tower with the famous Gothic double spiral staircase being built . In 1496 he had the Jews expelled from Styria. These were settled in Lower Austria and western Hungary.

The rise of the Habsburgs to world power began with Maximilian I and his descendants. The Duchy of Styria was only a relatively insignificant part of its empire, "in which the sun never set". In 1497, by order of Maximilian I, all Jews were expelled from Styria. With the expulsion, many communities lost the important economic power of the Jewish traders.

Early modern times: religious dispute and Turkish wars (1500–1740)

The teachings of the German reformers found their way into Styria as early as 1530 and the teachings of Martin Luther spread rapidly . The reasons for this were poor social and economic conditions and grievances in the church. The nobility quickly joined Protestantism . The main reason for this was that it demanded the return of the church to apostolic poverty, which would have resulted in the renunciation of its rich goods and the fall of the church goods to the nobility. In 1547 the governor Hans Ungnad claimed free religious practice at the Diet of Augsburg , but this could only be coerced from Archduke Charles II at the Diets of Bruck in 1575 and 1578 . Archduke Karl, the youngest son of Emperor Ferdinand I , fell to Inner Austria during the second Habsburg division in 1564. Archduke Karl called on the Jesuits for help in 1570 to prevent the new teaching from spreading, and in 1585 he founded the University of Graz .

The Turkish taxes introduced for the necessary defense against the Turks and the increased demands of their manorial rule burdened the peasants. In 1525, a great peasants' war also hit Styria from Salzburg. Farmers and miners conquered the mining town of Schladming and imprisoned Governor Siegmund von Dietrichstein . Schladming was recaptured by Count Niklas Salm , burned down and lost its town charter. In addition to the farmers, the ecclesiastical property was also burdened by special taxes such as the third , the fourth or the confiscation of church treasures.

Through contracts with the dioceses of Bamberg (from January 27, 1535 with Bishop Weigand von Redwitz ) and Salzburg (from October 25, 1535 as a recess from Vienna with Cardinal Archbishop Matthäus Lang von Wellenburg ) the Habsburgs obtained complete sovereignty over the possessions in Styria of these dioceses.

After the battle of Mohács in 1526, in which the Hungarian army suffered a crushing defeat against the Turks, the Turks were able to capture large parts of Hungary and Croatia and integrate them into the Ottoman Empire. This brought them even closer to Styria. The defensive struggle against the Turks was waged with varying degrees of success. Archduke Charles II had temporarily taken over the top management at the borders. He founded an inner Austrian court war council and had the Karlovac fortress named after him built in 1579 . Domenico dell'Allio re- fortifies the Graz Schloßberg . The state armory , which still exists today, was built, in which there was space for numerous military equipment. The inner Austrian provinces agreed to finance the Croatian and Slavonian military border , which was built to protect the Habsburg hereditary lands . Karl of Inner Austria was buried in the mausoleum of the basilica of Seckau . He was succeeded by his son Ferdinand II.

Ferdinand II , who took over the government in 1596, was determined to lead the Counter-Reformation to victory. He declared his father Charles II's letter of freedom canceled and in 1598 expelled Protestant teachers and preachers from the country. A Catholic Counter-Reformation Commission set up on this ordered all Protestant citizens either to convert to the Catholic religion or to emigrate. The religious commissions, consisting of clergymen, civil servants and soldiers, traveled through the country and emphatically ensured the recatholization of all strata of the population, with the exception of the nobility. Many Protestants swore off their confession at the time, but a significant number left their homeland. Among the Protestants expelled from Graz was Johannes Kepler , who taught mathematics from 1594 to 1600 at the Protestant collegiate school there. Only in the inaccessible mountains of Upper Styria, for example in Ramsau am Dachstein or in Wald am Schoberpaß , did the Protestant faith quietly survive in individual peasant families, which is why, after Joseph II proclaimed freedom of belief in 1781 , the first few Protestants Congregations constituted. Ferdinand II initially granted freedom of belief to the Styrian nobility, but in 1628 the aristocrats were also asked to profess Catholicism or to emigrate. The number of nobles who emigrated as a result was significant.

Recatholization restored the country's religious unity. A major subject of dispute between the sovereign and the estates was resolved. The will of the archduke had prevailed over that of the nobility and the sovereign power was sustainably strengthened. In 1619, Ferdinand II united almost all of the Habsburg lands in his hand, as there were no heirs to the other Habsburg lines. Again it was the Styrian-Inner-Austrian Habsburg line that continued the Habsburg line of succession in Austria. He became king of Bohemia and Hungary and soon afterwards also emperor. He moved his residence to Vienna, and Graz became a provincial city, which had an impact on further urban development and construction activity. The last major construction project of the inner Austrian Habsburgs in Graz was the mausoleum south of the cathedral.

Styria was spared the horrors of the Thirty Years' War , but the country suffered badly from the high taxes on the costs of the war and from the high prices and famine. Fortunately, the Turks, by and large, kept peace during this period. Occasional attacks and incursions by smaller groups kept occurring.

In addition to the wars, the plague spreads from 1680 to 1716, which reached as far as remote areas of the Koralmzug, created heavy burdens for the country. Guarded road and locking up were (Verhackungen, at the national borders barricades erected), the neighboring countries, for the movement of people and goods. B. in the Koralm area to and from Carinthia, and thus should make the spread of the epidemic more difficult.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the Styrian iron industry got into a difficult economic situation. Especially in Innerberg , the situation was so bad that the government was forced to intervene. In 1625 the three members of the iron industry were united to form the Innerberger Main Union , the largest commercial enterprise in Austria at that time. A chamber count was used for monitoring. The situation of the iron industry was gradually improved again. On the Vordernberger side of the ore mountain, the trades retained their independence. Only the purchase of wood and coal took place jointly within the framework of the “Vordernberger Radmeister community”.

After the beginning of the 16th century, the Renaissance found its way into Styria and determined the building attitudes of the nobility and the wealthy bourgeoisie. Significant Renaissance buildings are the country house , which is the former seat of the estates, a number of other aristocratic palaces and town houses in the center of Graz, Eggenberg Castle and some Styrian castles. After the Counter Reformation, the magnificent buildings dominated the church, such as the St. Lambrecht monastery . The most beautiful baroque church and monastery buildings in the country include the collegiate church of Pöllau and that of Vorau , the Grazer Barmherzigenkirche, the Mariatrost basilica , the basilica of Mariazell , the pilgrimage church Frauenberg an der Enns and the famous Admont abbey library . The most important baroque sculptor in Styria was the monastery sculptor of Admont Josef Stammel .

1663 the Turks declared Emperor Leopold I. war. Before the Turkish army could penetrate Styria, it was defeated by the imperial troops under the command of Count Raimondo Montecuccoli in the battle of Mogersdorf . In the aftermath of this war there was a conspiracy of Hungarian nobles. The Styrian Count Hans Erasmus von Tattenbach was also involved in this magnate conspiracy . The conspiracy became known and Count Tattenbach was publicly executed in front of the Graz town hall in 1671, which was an exciting event in the provincial town.

In 1683 there was the second Turkish siege of Vienna . Many refugees came to Styria from Vienna and Lower Austria. The successful defense of Vienna and the victory in the Battle of the Kahlenberg freed the Styrians from worrying about their safety and ended the Turkish threat to the country. In the following decades there were several more distant battles and confrontations with the Turks, in which Styrians were also involved as soldiers, but no more as peasants or citizens attacked. However, from 1704 to 1711 the Hungarian rebellious Kuruzen devastated Eastern Styria.

The Duchy of Styria remained a part of the Habsburg Empire until 1918, but since Charles VI. (1728) no more sovereigns accepted the homage, and since 1730 the regional hand-fests have not been confirmed.

Age of Enlightened Absolutism (1740–1792)

In 1740 Maria Theresa inherited a difficult legacy. The state was surrounded by enemies, the state coffers were empty and the army was neglected. Styria was not directly affected by the War of the Austrian Succession , but recruiting and increased tax burdens depressed the country.

After the end of the war, radical reforms and changes began. The influence of the Styrian estates was pushed back further. The administration was centralized and the last inner Austrian authorities in Graz were dissolved and a gubernium for Styria, Carinthia, Krain and Görz-Gradiska was set up. Styria was divided into five districts, namely Judenburg, Bruck an der Mur, Graz, Marburg and Cilli . The respective district captain had to make the task for receipt of taxes to support the recruitment to monitor public life and the basic rule to supervise. The tax exemption of aristocratic landed property was lifted and a land survey was made in order to create the Theresian Cadastre , a register of all properties. An army reform reorganized the legal system and the legal system was redesigned. In 1753 Maria Theresa ordered a census by parish, which was followed by a second census in 1770. In the latter, the parishes were divided into numbering sections and the houses were numbered for the first time. This division into advertising districts was originally used for recruiting. They subsequently formed the basis for the tax communities introduced under Emperor Joseph II and the later cadastral communities . In the course of the educational reform, the University of Graz was given a law faculty in 1778.

Emperor Joseph II went even further and reduced the scanty remnants of the self-government of the cities and markets. He wanted to make the monarchy an absolutely governed unitary state. With the tolerance patent , the emperor announced that all members of the evangelical confessions and the Greek Orthodox Church would tolerate their religion.

The emperor exercised strict supervision over the Catholic Church. Papal bulls could only be published with the imperial approval. The Jesuit order was abolished in 1773 and its property confiscated. Furthermore, Joseph II changed the administrative division of the church from the Middle Ages, dividing Styria into three dioceses. The Seckau diocese with its seat in Graz comprised Graz and Eastern and Western Styria, the Leoben diocese Upper Styria and the Lavant diocese with its seat in Marburg the Lower Styria. A large number of new parishes were established and 32 Styrian monasteries, including the old monasteries Göß , St. Lambrecht , Seckau , were abolished, Admont , Vorau and Rein were spared. Long-term pilgrimages were also prohibited.

Coalition Wars, Vormärz and Revolution in Styria (1792–1848)

With the accession to the throne of King Franz II , since 1804 as Emperor of Austria Franz I, in 1792 the time of the great reforms came to an end. Other events caught people's attention. The French Revolution and the subsequent rise of General Napoléon Bonaparte to Emperor Napoleon I kept people in suspense. All of Europe was affected by the wars that followed, which lasted until 1815.

In 1797 the French army invaded Styria via the Neumarkter Sattel . Soon afterwards Napoléon came to Graz, where he stayed for two days. Peace was negotiated in Leoben. The preliminary peace of Leoben was signed by Napoléon and the representatives of Austria in the Eggenwald garden house . Then the French troops withdrew again. In 1801 the French were there again and occupied parts of Styria and again harassed the population with requisitions and contributions . It was even worse in 1805, when Mariazell and Judenburg were badly damaged. 1804-1806, the previous state political framework in which Styria was was from Napoleon virtually destroyed the Holy Roman Empire to the Empire of Austria reshaped.

In 1809 another war broke out and it was again unhappy for Austria. A rearguard of the Austrian army was defeated at St. Michael and the way to Graz was again open to the French. After the defeat of the Austrians in the Battle of Wagram , Napoleon dictated harsh peace conditions in the Treaty of Schönbrunn , which resulted in great territorial losses for the Austrian Empire. One condition that affected Styria was the required razing of the fortifications on the Graz Schloßberg , which was carried out immediately in 1809. Only the clock tower and the bell tower remained because they were bought by the people of Graz. The coalition wars lasted with interruptions until 1815. However, Styria was no longer directly affected as a war zone.

The wars in defense of Napoleon cost the country many victims. At the end of more than twenty years of war, Styria was exhausted, the number of inhabitants had declined, and prosperity had shrunk.

After the long war, most people wanted "peace and order". A general indifference to political events spread. The prevailing absolutism tolerated no suggestions for improvement, saw in them nothing but incitement to rebellion and insubordination, and in the situation referred to as Biedermeier , restricted civil freedom of action to private life. Public life has been bureaucratised to an unprecedented extent. Nobility and officers were given preference in all areas and displayed a haughty and arrogant attitude towards the other classes of the population. State Chancellor Metternich , in agreement with Emperor Franz I, set up a police state that included censorship and informers . The time before the March Revolution of 1848/49 is known as Vormärz .

Archduke Johann was a ray of hope in the conditions of the time, which were often perceived as unsatisfactory . The younger brother of Emperor Franz I worked privately as an important sponsor and modernizer of Styria. The country and its people owed and have much to thank him for, both in the areas of regional and folklore, technical sciences, agriculture, mining and metallurgy, national costume and folk music, as well as providing the impetus for founding many of them today existing institutions in Styria.

His solidarity with the people was also expressed through his frequent stays and his residence in Styria and, above all, through his marriage to the middle-class Aussee postmaster's daughter Anna Plochl .

In the first half of the 19th century, the mining area of Upper Styria was one of the centers of industrialization; The traditional ironmongery industry provided a boost. Franz Mayr built the Franzenshütte in Donawitz from 1835–1837 , the most modern ironworks in Austria at the time, which was independent of charcoal.

In 1844, the southern section of the Mürzzuschlag - Graz railway was the first to open in Styria ; later the southern railway, connection to the port of Trieste , became one of the most important railway lines of the monarchy. In 1846 Styria had around one million inhabitants, of which around 600,000 lived within today's national borders. As almost everywhere in Europe, the population increased sharply at the time.

Exciting news came from abroad as early as the beginning of the revolutionary year of 1848. In Styria, especially in Graz, the uprising only broke out when the outbreak of the revolution in Vienna became known in March. Various petitions demanded freedom of teaching , freedom of learning, freedom of the press , freedom of the administration of justice, abolition of the manorial jurisdiction and free municipal administration. Archduke Johann acted in 1848/49 as the elected imperial administrator for the German national state, which the Frankfurt National Assembly had unsuccessfully strived for, to which Styria would also have belonged. With the suppression of the revolution in Vienna in October 1848, the revolutionary efforts in Styria also came to an end.

Industrial Revolution - Social and National Contrasts (1849–1918)

Peasants Liberation

Despite the failure of the goals of the revolution of 1848/49 , there were lasting successes that were not revised by the victorious counter-revolution. The final dissolution of the feudal order and the abolition of hereditary subservience and peasant labor in the Austrian Empire as well as the abolition of the secret inquisition justice of the Restoration and Vormärz period are among them.

The implementation of the basic discharge was tackled quickly. As a result, the peasants were finally turned into equal citizens. This required many related changes. The "peasant liberation" required compensation from the landlords. A third of the compensation had to be paid by the farmers, a second third was raised from state funds and the rest was canceled.

The settlement of these compensation payments to the total of 1,496 manors in Styria took several years. It also relieved the landlords of the public burdens they had previously borne, such as the judiciary and security in the country. The state took on these burdens. For this the judiciary and the administration had to be reorganized. The court organization in Austria was reorganized and in 1859 and 1868 the district authorities , as they basically still exist today, were created. The gendarmerie was founded in 1849 to provide security .

Community autonomy

Finally, the local churches were also created. Until then, in addition to the landlords, whose subjects were mostly scattered in different areas, there had been only 16 sovereign cities and 20 sovereign markets, which more or less administered themselves. The provisional municipal law of 1849 created local churches. The law was soon repealed, but through the Reichsgemeindegesetz of 1862, free municipal administration was implemented. However , there was still no general, equal and free right to vote for community representatives. Initially, only male community citizens who paid direct taxes, as well as clergy, civil servants and similar persons were eligible to vote.

Road to constitutional monarchy

After the collapse of the revolution, the young Emperor Franz Joseph I and his advisors tried to continue to govern the Austrian Empire in an absolutist way. However, this attempt collapsed miserably on the battlefields of Italy in the Sardinian War in 1859, since after this personal defeat of the emperor it could no longer be enforced domestically against the bourgeoisie.

The October diploma of 1860 and the February patent of 1861 were the first small steps towards a constitutional monarchy . Since then, the Styrian Landtag has existed in Graz as an elected state parliament (at that time by a long way not by all citizens). The forerunner of the republican state government was the state committee consisting of state parliament members , whose chairman appointed by the emperor and also the state parliament president was called the governor . The emperor and the kk government were represented in Graz by a governor . Most of the decisions of the Landtag and the Provincial Committee had to be submitted to the governor in Vienna for approval, which was granted or refused by the Kaiser himself or by the competent minister on his behalf.

The constitutional form of government was fully developed in the December constitution of 1867 after the domestic political peace agreement with the obstinate Hungarian nobility, which had followed the defeat of 1866 by Prussia . The Crown Land, Duchy of Styria, was now one of 17 of the kingdoms and states represented in the Reichsrat and sent members of the Reichsrat , the parliament in Vienna.

industrialization

The population increase in Styria in the period from 1849 to 1914 was almost 50 percent. Never before or since has Styria seen such a strong increase in population. The main reason for this was the flourishing of industry. The second half of the 19th century can be called the age of the industrial revolution in Styria. Large-scale industrial companies emerged in large parts of the country, benefiting from the legally stipulated freedom of trade. Commercial and agricultural workers migrated to industry, which paid higher wages and provided more favorable working conditions.

The iron industry was the basis of the Styrian economy. In 1881 the Österreichisch-Alpine Montangesellschaft was founded, which achieved a strong increase in production. Most of the steel industries were in the Upper Styrian Murtal and Mürz Valley , in addition to Donawitz also in Kapfenberg , Bruck an der Mur , Judenburg , Mürzzuschlag and in smaller towns. A number of new companies also emerged in Graz. Furthermore, new mining operations emerged, for example for magnesite in the Veitsch and other places. Large lignite mines were built in Fohnsdorf , Seegraben near Leoben , Köflach , Wies and near Trifail (Slov. Trbovlje ) in Lower Styria . Further prosperous companies emerged in the emerging paper and pulp industry, in cement production and in the milling industry. The beer breweries in Graz and Göss near Leoben became large companies.

The industry went through a reallocation process. New trades were added, some old trades flourished, while others perished. This process has not happened without struggles between small businesses and factories.

During this period almost the entire country was opened up by railroad lines. The Semmering Railway, opened in 1854, completed the southern railway, which ran from Vienna to Laibach , the capital of the neighboring country of Krain to the south; In 1857 the extension to Trieste was completed (see Spielfeld-Straß-Trieste railway line ). The other Styrian railway lines included a. Rudolfsbahn , Erzbergbahn , Graz-Köflacher Eisenbahn , Steirische Ostbahn and Drautalbahn . The railway buildings changed the traffic; the streets were deserted and new places flourished at the railroad junctions.

The peasant class had nothing to gain in the economic boom of the bourgeois-liberal epoch. Many farmers or farmers' sons emigrated as workers to industry or to the railroad and post office. The distress of the farmers prompted the state administration to support the agricultural cooperative system as planned .

Nationalism of the Germans and the Slovenes

Since the French Revolution, nationalism has become increasingly important. Relatively late, and not until the second half of the 19th century, ethnicity and language became central criteria for a nation. This Europe-wide development naturally had a negative effect on a multiethnic state such as the Habsburg monarchy .

In the Styrian Landtag , which has existed since 1861, the national contradiction between German and Slovenian Styrians became an issue at the beginning of parliamentary life in Styria. The Slovenes felt set back by the distribution of mandates and were constantly criticizing this. The German ( self-denominated! ) Bourgeoisie, however, whose representatives had a secure majority, did not want to give up any of their privileges. Since the Slovenes made up about a third of the population at that time and had no prospect of ever winning a majority in the state parliament, their main demand was very soon to separate the Slovenian-speaking districts of the country and to unite them with the Slovenian landscapes of Carinthia and Carniola to unite their own crown land .

On the other hand, the representatives of Central Styria and Upper Styria did not want to “hand over” the German bourgeoisie living in the Lower Styrian cities and markets to a Slovenian majority. The fronts hardened and the attitude of both nationalities became adamant.

The German national circles felt themselves to be part of the comprehensive many millions of people of German nationhood the few Slovenians against mentally and culturally superior and brought this opinion more often clearly expressed. The equality of Austrian citizens of all nationalities, anchored in the constitution since 1867, was avoided in practice by the German-Austrians (analogous to the behavior of the Magyars in the Kingdom of Hungary ) wherever possible. This attitude angered the Slovenes and they felt honored. Tensions between German-speaking and Slovene-speaking Styrians increased, but without having the same effects as in Bohemia and Moravia . The focal points were the German cities in the Slovenian area, next to Marburg ( Maribor ) especially Cilli ( Celje ). In 1895 the Emperor in Cilli (based on the Marburg model) approved a state secondary school with German-Slovenian teaching language ; the Reichsrat decided on the necessary budget resources.

In 1880 a census took place in Graz, in which for the first time the colloquial language was asked. 96 percent of the population of Graz stated that German was the colloquial language. The proportion of the Slovene-speaking population, the largest non-German language group, was 1.02%; this, although Styria was a bilingual crown land, with around a third of the Slovene-speaking population, mainly in Lower Styria. Based on an evaluation of the communities of origin, it can be assumed that the proportion of Slovenian immigrants was far higher than was evident from the census. Only a tiny fraction of these immigrants gave Slovene as a colloquial language.

Since the 1870s, Graz has developed a self-image as the “last large German city in the south-east” with a national and cultural mission. With the guiding principles of “German” and “progressive”, the Styrian capital was considered the most radical city in Austria, both in terms of its liberal, anti-clerical and German national stance.

In addition to the national contrasts, there were also political tensions between the liberal and Catholic-conservative circles of the population. The workforce also began to organize and fought primarily for wage increases, shortening the daily working hours, which were between 12 and 14 hours, against the hardship of illness and in old age, for which no provision was made, and also against the social Contempt shown to the worker by the bourgeoisie.

Education and culture

As almost everywhere in Europe, in Styria the period between 1848 and 1918 was a time of lively intellectual activity. The number of students and professors at the Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz and the other universities multiplied. It was possible to win important scholars as professors, some of whom achieved international renown. The Graz University of Technology was taken over by the state in 1874 and put on an equal footing with the other universities. The Montanuniversität Leoben received the rank of university in 1906. The first women were admitted to university at the end of the 19th century.

The rest of the school system also showed a strong upswing. With the Reich Primary School Act of 1869, school supervision, which had previously been the responsibility of the church, was transferred to the state school board. The theater experienced a heyday. The Graz Opera House was built in 1899 . In addition to the Graz playhouse, there were five stages in other Styrian locations. From the ranks of Styrian poets and writers, especially Peter Rosegger should be mentioned. His rise from the forest farmer's boy to a famous writer was unique for Styria, as was the worldwide success of his poems and novels, which are characterized above all by idealizing agriculture. His German nationalism and the associated rejection of everything "Slavic" prevented the award of a Nobel Prize for literature.

General male suffrage

In 1906/07 following mass demonstrations organized by socialists in the Reichsrat the introduction of equal male suffrage was discussed; each vote should now have the same weight. Aristocracy and large estates, such as B. the Styrian landowner deputy Karl Graf Stürgkh , resolutely opposed the submission of the kk government of Freiherr von Beck , which was decided by both houses of the Reichsrat and approved by the emperor. In 1907 and 1911, therefore, elections to the Reichsrat were held according to the general, equal, direct and secret male suffrage, which was of particular benefit to the two mass parties, the Christian Socialists and the Socialists . Of the now 516 MPs, 30 were to be elected in the Duchy of Styria. In cities like Graz, the German People's Party remained a leading force. The provincial parliaments of old Austria remained until 1918 with the previous privileges that disadvantaged the poorer classes.

Rank among the crown lands

In 1910 the Duchy of Styria took up the area of Cisleithania , around 300,700 km², 22,425 km² or 7.5%. Of the approximately 30 million inhabitants of old Austria, 1.44 million or 4.8% came from Styria. The crown land was the fourth largest in terms of area and, in terms of population, the fifth largest of the kingdoms and countries represented in the Imperial Council. (The total monarchy with Hungary and Bosnia-Herzegovina covered 676,600 km² and had 52.8 million inhabitants, including 2.7% Styrians on 3.3% of its area.)

Disintegration of the Duchy of Styria

The contrasts between German and Slovenian Styrians were temporarily reduced by Italy's entry into World War I on the side of Austria-Hungary's opponents, as the Slovenes also wanted to fend off the Italians' territorial claims . The longer the war lasted and the more the economic and supply situation deteriorated and the number of war victims grew, the more the longing for peace increased. In the Reichsrat, which was convened again by Emperor Karl I in the spring of 1917, representatives of all nationalities announced the political goals they would pursue after the war. They were concerned with political units according to national aspects; Dynastic loyalty or the old Austrian state consciousness no longer seemed appropriate. The Czechs led the way in these endeavors , as the state they planned had received the recognition of the Triple Entente as an ally by their politicians in exile during the war .

In reaction to this, on October 21, 1918 (the military collapse of the Central Powers was imminent), the German Reichsrat members in Vienna formed the Provisional National Assembly , which on October 30, 1918 elected the first government for German Austria . On October 29, 1918, Krain broke its ties to the monarchy, and on October 30, the SHS state was proclaimed, which Lower Styria and Krain joined.

A “welfare committee” was formed in Graz to take care of the supply of the country. A provisional state assembly, which was formed by the country's three major German parties, Christian Socialists , Socialists and German Nationalists , elected a new state government, which took on a difficult office.

On November 6, 1918, the regional assembly resolved unanimously to join German-Austria , referring to the right of self-determination of the peoples and stipulated that “the other tribe resident in the previous crown land renounced the previously common state because of the right of self-determination of the peoples with its rest Volksgenossen established their own national state and thereby also dissolved the community of all previous institutions of the Duchy of Styria ”. The majority of the German-Styrian population experienced the proclamation of the republic on November 12, 1918, starving and, according to the decision of the Provisional National Assembly, should be connected with the annexation to the German republic.

First Republic (1918–1938)

For Styria as a federal state of the Republic of Austria (as the state has been called since October 21, 1919 on the basis of the ratification of the peace treaty of Saint-Germain ), one of the first tasks was to democratize the state constitution . The executive power was transferred to the state government , which was elected by the state parliament and consisted of the governor , two deputies of the governor and several regional councilors. The universal and equal suffrage for men and women and proportional representation in place of the previously applicable electoral system were introduced. In 1920, the Federal Constitution regulated the powers of the federal states vis-à-vis the state as a whole. The principle of municipal self-government was adopted from the constitution of the monarchy . The right to vote for classes in the municipalities also fell away and gave way to a democratic order.

Unresolved issue of the southern border and loss of Lower Styria

The provisional state assembly wanted to leave the definition of the southern border of the state to negotiations with the Slovenes and the peace treaty to be concluded and assumed that the Drau region would fall to Austria. The Slovenes, however, under the previous kuk major and now Slovenian general Rudolf Maister , who was stationed in Marburg an der Drau , immediately set about creating facts. Austro-Hungarian troops and Slovenian volunteers who placed themselves under his command occupied Lower Styria without encountering any significant resistance from the German-speaking minority. The playing field and places north of the Mur on the railway to Radkersburg were also occupied in order to secure the northern Slovenian border.

A large number of German-speaking Lower Styrians and officials of the monarchy, who had their home elsewhere, left the Slovene-occupied territories and moved to the areas that remained with Austria; some were also expelled. In Radkersburg and the surrounding area and also in the Soboth there was armed resistance against the occupation, which meant that the areas remained with Austrian Styria.

The predominantly German-speaking city of Marburg posed a special problem, which together with its neighboring villages formed a German-speaking island about 15 kilometers south of the new state border. A few weeks in November 1918, the Marburgers even set up a vigilante group, albeit in vain, to prevent the Slovenes from taking power. German Austria claimed the city for itself and also wanted the 15 km wide, Slovenian-populated area between Marburg and the southern border of the German settlement area to be left with Austria.

During a demonstration by German-speaking citizens on January 27, 1919, Slovenian soldiers shot at unarmed demonstrators. 13 German civilians in Marburg were killed and around 60 wounded, which aroused horror and indignation among all “German-Austrian” Lower Styrians, but also intimidated the German-Austrian Marburgs.

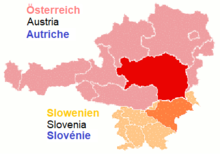

However, the Treaty of Saint-Germain took no account of these wishes. He not only disregarded the German language islands, but also awarded the purely German-speaking Abstaller basin to the SHS state ; German-Austrian enclaves in Slovenia were not considered; the whole of Lower Styria remained with Slovenia under international law. As a result, Austrian Styria shrank by 6,024 km² to 16,401 km² compared to the former duchy, which is second place among the later nine federal states of the republic.

In the SHS state, Lower Styria was initially merged with Krain to form the Draubanate . Today it forms about the eastern third of Slovenia with the name Štajerska (= Styria) .

Trauma and economic hardship

For the majority of German-speaking Austrians, the collapse of the capital k. u. k. Dual monarchy a traumatic event. The new small state lacked self-confidence from the start. Large sections of the population and politicians supported the annexation to Germany, which was therefore decided on November 12, 1918 at the same time as German Austria was declared a republic.

In St. Germain Austria signed (the state name German Austria was by the victors not accepted) but that it independently and by Germany in the long term regardless 'll stay (the German Reich was analogous to the Treaty of Versailles obliged). In Styria, German nationalism and, in later years, National Socialism became a determining factor, which in 1921 led to the attempt by Styria to go it alone on the follow-up question under Governor Anton Rintelen . However, under pressure from the victorious Allied powers, the referendum that Rintelen had called on this issue had to be canceled.

The breakup of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy was followed by great economic difficulties. The supply of essential goods was very poor. The terrible winter of 1918/19 could only be survived with the help of actions in the neutral countries of Switzerland , the Netherlands and Sweden . The worst evil, however, was the decline in the value of money. A hyperinflation consumed on old assets. The middle class , which had been used from time immemorial, his savings in banks or in government securities to invest, impoverished and with it most of the rest of the population. Only when the famine was averted and the currency stabilized - the shilling was introduced in 1925 - was it possible to think about the successful rebuilding of the economy. The following slight economic upswing lasted only until 1929 and ended with the Great Depression .

Many sectors of the Styrian economy were affected by the global economic crisis. They felt the Styrian iron industry and lignite mining particularly hard . There were operational restrictions and layoffs. The worst scourge of the interwar period was unemployment , which had hitherto reached an unimaginably high level. With it, the need grew, especially in the industrial areas.

Despite the material limitations, the sciences flourished. The scientists Fritz Pregl , Otto Loewi , Victor Franz Hess and the atomic physicist Erwin Schrödinger , who work at the Styrian universities, received the Nobel Prize . The German Alfred Wegener , who worked as a university professor in Graz, discovered continental drift .

Paths to dictatorship

From 1930, political tensions increased. The political parties surrounded themselves with paramilitary groups. There were frequent clashes. The Heimwehr won supporters primarily among the rural population, while the workers in the industrial towns formed a solid bulwark of social democracy. The Republican Protection Association was the paramilitary organization of the Social Democrats. In September 1931 the Heimwehr attempted a putsch under the Judenburg lawyer Walter Pfrimer , but it collapsed very quickly. Pfrimer was charged with high treason but acquitted. The National Socialists also began to make themselves more and more noticeable after 1930. In the municipal council elections in 1932 , the NSDAP was able to increase its share of the vote sixfold compared to 1928. The Nazi movement, which began in June 1933, was not as firmly anchored in any other Austrian federal state as in Styria.

After the Christian Social Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss used a parliamentary crisis in 1933 to install an authoritarian corporate state government , the Social Democratic uprising broke out openly in February 1934 . Styria was also badly affected by this, where social democratic workers in Graz and the Upper Styrian industrial cities called a general strike and took up arms. The fight cost numerous deaths on both sides, which were made even more numerous by the harsh criminal court of the victorious Patriotic Front . The Styrian workers' leader Koloman Wallisch was sentenced to death by a court martial. A total of 59 people were killed in the February uprising in Styria in 1934; the Social Democratic Labor Party has now been banned.

After the “ seizure of power ” in Germany in 1933, National Socialist propaganda increased steadily in the country. As in the rest of Germany, the NSDAP used acts of violence in Styria. Explosive attacks alternated with swastika paintings. During the July coup of 1934 there was, on the one hand, the attack on the Federal Chancellery in Vienna and the murder of Dollfuss and, on the other hand, triggered by this, the Nazi uprising in several federal states, which was practically autonomous.

During this uprising, the Austrian National Socialists attacked gendarmerie posts, post offices and other public institutions in many Styrian places and arrested political opponents. After a day, the uprising collapsed after the deployment of the federal army. There were a total of 223 deaths on both sides in Austria, 96 of them in Styria. Two putschists from the Ennstal were executed. About 13,000 to 15,000 insurgents were arrested, at least temporarily. Some of them were imprisoned for a long time, many of them were held in the detention camp in Wöllersdorf . Many Social Democrats had been interned there since February 1934. Many participants in the Nazi coup fled abroad, mostly to Germany and Yugoslavia . Now the NSDAP has also been banned in Austria.

The further political development of Styria was determined from outside. Due to the cooperation of the German Reich with fascist Italy, Austria had little opportunity for an independent policy. Austria was deeply divided politically, had lived under the Austro-Fascist dictatorship since 1933/34 and did not come out of the economic crisis while Germany's war economy was booming. In 1938 the number of statistically recorded unemployed in Austria was 401,000. In addition, there was the “invisible” unemployment, which was estimated by the Institute for Economic Research at 300,000. At the end of January 1938 there were probably around 700,000 unemployed in Austria: more than 20 percent of the workforce.

Follow-up efforts

The "connection" of Austria to the German Empire was one of Adolf Hitler's declared goals. The seemingly hopeless political and economic situation in Austria had given impetus to the deeply rooted idea of annexation to Germany. In the years before the Anschluss, the illegal NSDAP became a mass movement: workers, petty bourgeois, farmers, farm workers and students were there. In February 1938, Hitler increased the pressure on the Austrian Schuschnigg government . This lifted the party ban for the Austrian National Socialists, and two National Socialists were accepted as government members, including Arthur Seyß-Inquart as Minister of the Interior and Security.

In Styria in particular, the SA and HJ tested the limits of the new possibilities offered by the fact that Austria's police were now under a National Socialist minister. On February 19, 1938, a huge torchlight procession marched through the streets of Graz with swastika flags, ignoring the ban on gatherings . The university and the technical college had to be closed because of extensive National Socialist rallies. ... On February 21st, SA Brigadefuhrer Sigfried Uiberreither gave the order for readiness. Before the Federal Assembly on February 24, 1938, Schuschnigg emphasized the duty to use all of her efforts to preserve the unharmed freedom and independence of the Austrian fatherland.

Graz, "city of popular uprising"

The same day took place in Graz what the National Socialists soon called the “popular uprising”. Many responded to the call by the Nazi leadership in Graz to “decorate” the houses with swastika flags. Thousands of National Socialists occupied Graz's main square and forced the mayor to hoist the swastika flag at the town hall as well. This later earned Graz the Nazi designation “City of the People's Uprising” . At the end of February, army units were deployed in Styria against Nazi attacks. According to official reports, pupils only wanted to go back to school if they were allowed the Hitler salute, which happened on March 1, 1938.

The seizure of power at the local level continued locally even with the announcement of the suspension of the planned for March 13 referendum, but the final impetus was only the radio speech by Chancellor Schuschnigg to 19:47 . The Völkische Beobachter reported in its Vienna edition of March 12th in a special supplement : At 6 o'clock the news leaked through that the election had been postponed. The SA was standing within a quarter of an hour, and countless people were standing on the main square in Leoben . ... At the same time the executive put on swastika armbands . In 1942, Otto Reich von Rohrwig wrote that on the evening of March 10, 1938, National Socialist masses had passed through downtown Graz. SA-Uiberreither had decided to block the polling stations on the day of the vote .

On March 11, 1938, the shops in Graz were closed at noon; the armed forces took position at important points. In the evening, when the corporate state government Schuschnigg resigned, but Security Minister Arthur Seyß-Inquart announced on the radio that he would remain in office, the local National Socialists took over power in Graz. According to Hochfellner, 60,000 to 70,000 people celebrated the takeover on the main square .

On March 12th at 1:30 am, Governor Rolph Trummer resigned; the National Socialist Sepp Helfrich took over the office and held it until May 22, 1938, when Uiberreither was appointed Gauleiter and governor by Hitler. On March 12, 1938, Austria was occupied by the Wehrmacht . German troops moved in on a broad front from 8 a.m. At the same time, a wave of arrests began.

Nazi rule 1938–1945

The "connection" and its consequences

As a prelude to his propaganda trip through Austria for the “referendum” on the “Anschluss” that had already taken place , Hitler visited Graz on April 3rd and 4th, 1938. The event, which was broadcast on the radio, took place in front of 30,000 people in the assembly hall of a wagon factory that had been shut down for several years due to the global economic crisis. Then Hitler drove through the streets of Graz in a triumphal procession to the cheers of his supporters. Along the 4.3 kilometer route stood tens of thousands of Styrians who, organized by the NSDAP, had come to the state capital by special trains, buses and trucks to see the “Führer”. Bruno Kreisky said in 1988 about the citizens who did not cheer : ... the several of them were in the dark. They were either in their fields, or they prayed in the churches, or they cried at home - in any case they were not visible. But they were in the majority. There is no doubt about that. This corresponded to later estimates by the Gestapo , which assessed around a third of Austrians as supporters of the Third Reich , a third as neutral and a third as opponents of the regime.

Measures that were already effective or announced before the vote strengthened approval of the Nazi regime: people feedings, new hires in industry and business, wage increases, debt relief and loan campaigns for farmers, marital loans and child benefits, leisure and holiday campaigns and much more. After years of economic crisis and the corporate state dictatorship, which primarily wanted to save, this policy was well received. (The fact that the German Reich was already incurring debts that could only have been repaid through war profits and that it urgently needed the reserves of the Austrian National Bank remained hidden from most people.)

In the “referendum” on April 10, 1938, it was customary to cast the votes for Hitler openly and not to go to a polling booth. According to the official final result, 99.87% of the Styrians entitled to vote voted for the connection; 40,000 people were excluded from voting. The excluded included all those politically imprisoned, the Jews and other racially discriminated groups such as the Gypsies . This was pointed out on posters of the new rulers; anyone who was supposed to take part in the vote illegally was threatened with arrest sentences.

On April 1, 1938, the first transport, the Prominent Transport, of opponents of National Socialism from Austria to the Dachau concentration camp took place. Among them was the Styrian politician and later ÖVP Federal Chancellor Alfons Gorbach . In May the Nuremberg Race Laws , which had been in force in Germany since September 15, 1935, also came into effect in Austria to “protect German blood and German honor” . The persecution of the Jews began in March 1938 with humiliation of the approximately 3,000 people from Styria and initially “wild Aryanizations ” of Jewish property: “ Aryan ” neighbors or competitors took possession of Jewish shops, apartments and cars.

The state government was replaced in the spring of 1938 by a state governor who was only bound by instructions from Berlin; this was Sigfried Uiberreither , at the same time Gauleiter of the NSDAP and mostly referred to with this title. Southern Burgenland was annexed to the province of Styria on October 15, 1938 , while the Ausseer Land , which had been connected to Styria for more than 800 years, became part of Upper Austria . In 1939 the remaining former Austrian states were converted into Reichsgaue with the Ostmarkgesetz with a Reichsstatthalter at the head, who was mostly also the NSDAP Gauleiter. (The term Austria largely disappeared.)

By integrating the Styrian economy into German armaments planning and by obliging young men to do Reich labor and military service, mass unemployment was quickly overcome. A debt relief campaign for the farmers solidified the financial situation of the farms and saved thousands from foreclosure.

The National Socialist rulers endeavored to nip in the bud any criticism and doubts about the correctness of their measures and orders. One example of this are the severe punishments for listening to previously unknown crimes such as enemy broadcasters , degradation of military strength and offenses against the Malicious Act or the People's Pest Ordinance . Any skepticism expressed against the NSDAP, its representatives or the Wehrmacht (even only in the family circle) could have dire consequences thanks to informers and denunciations .

Over 10.5% of the " Volksgenossen " living in the Gau Styria (excluding Lower Styria) were NSDAP members in 1942, that is to say "party members" as it was called in Nazi jargon. This number of members corresponded to 15.5% of all Austrian National Socialists. With 30,530 illegals, i.e. members who were party members before 1938, Styria had the highest proportion of all federal states after Carinthia.

In the November pogrom of November 9, 1938, also known at the time as “Reichskristallnacht” , the Graz synagogue and the Jewish ceremonial hall were completely destroyed. In 1934, 1,720 people belonged to the Israelite religious community, that is 1.1% of the total population of Graz. Because of the terrorism practiced, 417 Jews from Graz emigrated to Palestine from March to November 1938 alone. Jews who remained in Graz had to move to Vienna, from where they were later deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp . In March 1940 Graz and Styria were considered “Jew-free”.

In order to suppress the influence of the Catholic Church as far as possible, numerous measures were taken, such as the closure of the Catholic private schools, the expropriation of monastery property, such as in Admont , Seckau, Vorau, Rein and St. Lambrecht, and the closure of the theological faculty at the University of Graz . Religious instruction was declared an optional subject. The church was no longer financed by the state, but by church contributions from the faithful. The now mandatory civil marriage made bride and groom independent from the church (Austria had also recognized church weddings). Official divorces became possible for Catholics as well. In 1945, the Second Republic of Austria took over both the church contribution regulation and civil marriage in its legal status.

Second World War

The Second World War began on September 1, 1939 . Now people's living conditions were increasingly determined by the necessities of war. According to Neugebauer, until 1940/41, because of the overcoming of mass unemployment, the non-war takeover of the Czech Republic and the subsequent “ lightning wars ” (e.g. the sudden defeat of Poland in just six weeks), party members agreed to the Nazi system.

This approval was countered by unobtrusive opposition from some of those who did not want to support the wars of aggression. The Gestapo was not able to end sabotage actions by railroad workers in Styria until 1941; Until then, wagons with loads for Wehrmacht purposes were often "mistakenly" given incorrect destination information, etc. etc. Centers of this resistance, which also included deliberate errors in assembly work on vehicles, were the main workshop in Knittelfeld and the railway junctions in Leoben and Bruck an der Mur .

When it became clear that a quick victory was not possible against the Soviet Union attacked in the summer of 1941 , Germany also declared war on the United States , the campaign in the east with the Battle of Stalingrad in 1942/43 turned into a gradual retreat and increasingly for leaders , People and fatherland were to be mourned fallen, the Nazi enthusiasm was significantly weaker. The regime now also exploited the fear of vengeance by the victorious Russians in order to keep the people in line and spoke of total war .

Soldiers from Styria fought in all units and on all fronts. Styrians were increasingly used in the mountain troops .

Lower Styria in Nazi Germany

At the beginning of April 1941, the Wehrmacht conquered Yugoslavia in the Balkan campaign , which was occupied and disbanded by Italy and Germany. Lower Styria and parts of Upper Carniola became part of the German Empire. Lower Styria was not directly connected to the Reichsgau Steiermark, but was managed as the " CdZ-area Lower Styria " (CdZ = head of civil administration). Hitler also appointed the Styrian Gauleiter Uiberreither as head of civil administration for Lower Styria.

A rigorous policy of Germanization began there . After the arrest of the Slovenian leadership and the dissolution of the Slovenian associations and cultural organizations, thousands of Slovenes were resettled to Serbia , Croatia and the " Altreich ". Furthermore, as early as May 1941, around 1200 younger teachers from Styria were assigned to work in Lower Styria and German was introduced as the language of instruction at around 400 schools instead of Slovene. With a few exceptions, Slovenes were no longer allowed to work as teachers.

The ruthless Germanization policy soon led to Slovenian counter-actions such as passive resistance, sabotage and attacks. The Nazi regime responded to these reactions with terror, such as the shooting of prisoners whose names were posted across the country as a deterrent. As the war continued, the partisans became more and more popular. The German minority in Lower Styria, even if they were not involved in the barbaric Germanization policy of the Nazi regime, paid for those of the Tito regime after the war with their summary expulsion and expropriation , personal persecution, imprisonment, torture and murder were initiated or tolerated.

The way to liberation, defeat, collapse

From August 1943, the Allies had established a second air front from southern Italy. This meant that Styria could also be reached by the Allied bombers. The first heavy bombing raids on Graz began on February 18, 1944 and then continuously at irregular intervals. With July 1944, the entire public life in Styria was adapted to the requirements of total warfare.

Particularly heavy bombing raids took place on October 16, 1944 on Graz and Zeltweg . On November 1, 1944, the Graz Opera was damaged by bombs. On November 6th there were heavy bombing raids on Kapfenberg and Judenburg , on November 17th on Graz, on December 11th again on Graz, Bruck an der Mur and Donawitz and on December 25th 1944 again on Graz. On February 23, 1945, the city center of Knittelfeld was destroyed by bombers. The people of Graz remember the devastating bombing raids on All Saints' Day in 1944 and on Easter Sunday in 1945. A total of 29,000 bombs were dropped in 56 attacks on Graz alone, which destroyed 7,800 buildings and 20,000 apartments. The area of action of the partisans from the Yugoslav region extended to the Koralpen region in western Styria in 1944/45. The murder of five partisans in a camp of the Reich Labor Service was dealt with in the Graz partisan murder trial.

At the beginning of 1945 thousands of Hungarian Jews were used as forced laborers in Eastern Styria to help defend the Southeast Wall against the advancing Red Army . Then they were driven to the Mauthausen concentration camp in a multi-part misery train . Many exhausted Jews who were brutally treated by the escort crews died on these death marches . On April 7, 1945, a massacre occurred at the Präbichl . Members of the Eisenerzer Volkssturm shot indiscriminately into a column of exhausted Jews. The massacre killed 200 Jews. In June 1946, ten men found guilty of the shootings were sentenced to death in the three iron ore trials and executed.

On March 29, 1945, Soviet soldiers of the 3rd Ukrainian Front crossed the border from Hungary to Reichsgau Styria near Klostermarienberg ( Burgenland ) north of the Geschrittenstein .

The Commanding General of the Military District XVIII General of the mountain troop Julius Ringel was the end of March, numerous replacement and training units in the form of alarm associations to the frontier and to the Semmering embarrassed, including many from Styria. While the units that were sent to the Oberwart district were largely lost in the attack by the 26th Soviet Army on April 5, the units deployed in the Semmering area, which were combined to form the 9th Mountain Division in the last weeks of the war , prevent the Red Army's breakthrough into Styria from the northeast.

The rapid advances of other Soviet units (XXX. Rifle Corps of the 26th Army, from April 12th also the V. Guards Cavalry Corps) in the north of Eastern Styria aimed to reach the Mürz Valley , to the east and north-east of To destroy Graz an der Lafnitz fighting 6th Army a third time in this war. With a local counter-offensive by the 117th Jäger Division and units of the 1st Panzer Division and the 1st People's Mountain Division brought up from the Balkans on the southern railway , the Soviet cavalry and rifle units were able to move towards the old Styrian-Burgenland units National borders are pushed back. These battles were often tough and bloody struggles for individual positions and locations. Several East Styrian places were seriously destroyed, farmsteads burned down and were looted. Two foreign SS divisions ( 5th SS Panzer Division 'Wiking' and 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS ) fought southeast of Graz to stop a second dangerous Soviet advance that was aimed via Feldbach .

Since the Soviets considered their goals in Styria to be achieved in the course of April, but there was still a need to consolidate their sphere of interest in what was then Czechoslovakia , the Soviet forces shifted north in the last weeks of April, so that the military The situation in Styria gradually calmed down.

The mobilization of units of the Volkssturm was militarily senseless , as they could not counter the Soviet offensive with anything essential. On May 7, 1945, the German army commanders ordered retreat movements. At the same time the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht was signed in Reims . The Second World War was over. In Lower Styria, Yugoslavia immediately took power again.