Grand Duchy of Hesse

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

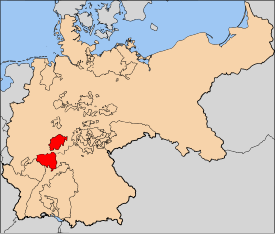

The Grand Duchy of Hesse , also called Grand Duchy of Hesse-Darmstadt , existed from 1806 to 1919. It emerged in 1806 from the Imperial Principality of the Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt . The ruling princes came from the House of Hesse and, following the expansion of their territory to include the areas on the left bank of the Rhine, based on the former Palatinate County near the Rhine, the title of Grand Duke of Hesse and near the Rhine . The capital and residence city was Darmstadt ; other important cities were Mainz , Offenbach , Worms and Giessen .

The Grand Duchy was a member state of the German Confederation from 1815 to 1866 . With its areas north of the Main, it belonged to the North German Confederation from 1867 to 1870 and was a member state of the German Empire from 1871 to 1919 . When the Weimar Republic came into being , it was converted into the People's State of Hesse , a forerunner of today's State of Hesse .

geography

The part of the Grand Duchy on the right bank of the Rhine stretched from the south and center of what is now the state of Hesse to almost Frankenberg in North Hesse, and the part on the left bank of the Rhine in what is now the state of Rhineland-Palatinate . In addition to the large plains of the Rhine ( Hessisches Ried ), Main and Wetterau , low mountain ranges such as the Vogelsberg , the so-called Hessian hinterland and the Odenwald also belonged to the state territory.

The national territory bordered

- in the west to the Prussian Rhine Province , to the Duchy of Nassau , from 1866 to the Kingdom of Prussia and the Province of Westphalia ,

- in the north and northeast to the Electorate of Hesse , from 1866 to the Kingdom of Prussia ,

- with exclaves in the north: District of Vöhl located between the Electorate of Hesse and the Principality of Waldeck and

- Eimelrod and Höringhausen , surrounded by the Principality of Waldeck

- in the east to the Kingdom of Bavaria ,

- to the Electoral Hesse exclave Amt Dorheim , which was annexed to the Grand Duchy in 1866.

- in the south at Baden ,

- with the exclave Wimpfen to Württemberg and Baden,

- with an exclave, which consisted of half of the village of Helmhof , in Baden,

- as well as the Palatinate (Bavaria), which also belongs to the Kingdom of Bavaria .

- Between the central and southern parts of the area lay the Free City of Frankfurt and the Electorate of Hesse, both of which became the Kingdom of Prussia in 1866.

- The northern ( district of Biedenkopf , called the Hessian hinterland ) and central area (the Hesse-Darmstadt region of Upper Hesse) were only connected to the Gießen area by an approximately 500 m wide Hessian area corridor near Heuchelheim, surrounded by the district of Wetzlar , an exclave of the Prussian Rhine province .

Hessen-Homburg fell as an inheritance to the Grand Duchy of Hessen-Darmstadt in 1866 , but had to be ceded to Prussia in the same year . The Biedenkopf district and the Hessian hinterland were also annexed by Prussia . Together with the states of Kurhessen , Duchy of Nassau and the Free City of Frankfurt , which were also conquered from Prussia in 1866 , these areas formed the new Prussian province of Hesse-Nassau from 1868 onwards .

history

Founded in 1806

The Landgraviate of Hessen-Darmstadt was elevated to a Grand Duchy by Napoleon . Landgrave Ludwig X of Hessen-Darmstadt stylized himself Grand Duke Ludewig I (with an extra "e") and, with a decree of August 13, 1806, not only announced the event that was pleasant for him, but also which territories he had collected on the basis of the Rhine Confederation Act would have. The background was that the now Grand Duke - still as a Landgrave - had tried to turn away from France under the protection of Prussia , a policy which, however , was heading towards the fall of the Landgraviate at the latest after the Battle of Austerlitz . At the last minute the landgrave was able to offer himself to Napoleon as a supplier of troops. Together with 15 other states, the Landgraviate left the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation and joined the Confederation of the Rhine . In addition to the increase in rank to the Grand Duchy, the Grand Duke was rewarded with territorial gains. It should be noted, however, that all the territories now won were subject to his national sovereignty, but the sovereignty rights of the previous rulers, the larger now class lords , were retained to a considerable extent. In detail, the Grand Duchy won in 1806:

- Now estates:

- the burgraviate of Friedberg ,

- the reign of Breuberg ,

- the rule of Habitzheim ,

- the county of Erbach ,

- the rule of Ilbenstadt ,

- the share of the rule Stolberg-Gedern in the county of Königstein ,

- the rule of Riedesel , as far as it bordered on the Grand Duchy,

- Parts of the possessions of the princes and counts of Solms (including the Assenheim and Rödelheim offices )

- the county of Wittgenstein and Berleburg and

- the Hessen-Homburg Office .

- Former imperial knightly areas:

- the rule slot ,

- the dominion of Franconian Crumbach (from Gemmingen )

- the office of Birkenau ( Wambolt von Umstadt )

- Georgenhausen (from Haxthausen )

- Messel (from Albini )

- Possessions of the Löw von Steinfurth :

- Albersbach (from Dalberg )

- the Hof Kreiswald ( Ulner von Dieburg )

- the Igelsbacher Höfe (from Belderbusch )

- Possessions of those of Frankenstein

- Melbach (called by Wetzel by Carben )

- Beienheim ( Rau von Holzhausen )

- Höchst (from Günderrode )

- Lindheim (from Specht )

- the inheritance of Staden

- the possessions of the coming of the Order of St. John in Nieder-Weisel

While the Landgraviate of Hessen-Darmstadt had around 210,000 inhabitants in its right-bank areas before the territorial gains, it was around 546,000 after 1806. At the same time, the Grand Duchy reached its largest area in terms of area with around 9,300 km² (166 square miles). Almost at the same time there was a radical upheaval in domestic politics: With two edicts of October 1, 1806, the privileges of the rural nobility - mainly financial - were largely abolished (the rural nobility became taxable) and the estates were abolished.

Development after 1806

On April 24, 1809, Napoléon ordered the dissolution of the Teutonic Order . The Grand Duchy received from its holdings

- Kloppenheim ,

- the Schiffenberg and

- The Order's possessions in Okarben .

From 1808 to 1810, consideration was given to introducing the Civil Code as a uniform law in the whole of the Grand Duchy of Hesse. But then the discussion was stopped by the conservative government under Friedrich August von Lichtenberg , which was opposed to social change .

On May 11, 1810, the Grand Duchy and the French Empire signed a state treaty with which France gave territories to the Grand Duchy that it had taken from Electorate Hesse in 1806. The treaty concluded in May was not signed by Napoléon until October 17, 1810. The Hessian occupation patent is dated November 10, 1810. The Grand Duchy acquired it in this way

- the Babenhausen office ,

- the Dorheim office ,

- the Herbstein office ,

- 7 ⁄ 12 from Heuchelheim ,

- the Munzenberg Office ,

- the office of Ortenberg and

- the Rodheim office .

The office of Babenhausen was assigned to the Principality of Starkenburg, everything else to the Principality of Upper Hesse.

In autumn 1810 there was a triangular deal between France, Hesse and the Grand Duchy of Baden . Baden put its own territories at the disposal of France, which then passed them on to the Grand Duchy of Hesse in a state treaty dated November 11, 1810. The Hessian occupation patent was dated November 13, 1810 and included

- the Amorbach office ,

- the Miltenberg office ,

- the Heubach office ,

- Laudenbach and

- Umpfenbach .

Congress of Vienna and subsequent period

In 1815 the Grand Duchy joined the German Confederation .

At the Congress of Vienna (1815), the Grand Duke of Hesse was awarded 140,000 souls in the former Donnersberg department as compensation for the Duchy of Westphalia, which had ceded to Prussia . Due to the turmoil caused by the rule of the Hundred Days , the return of Napoleon from exile, Austria , Prussia and the Grand Duchy of Hesse only concluded the State Treaty on June 30, 1816, which regulated the details. In terms of content, it was more extensive than what had been decided in Vienna last year. There were further border adjustments and the exchange of smaller areas with neighboring states, for example with the Electorate of Hesse and the Kingdom of Bavaria . The territorial changes of 1816/1817 for the Grand Duchy were as follows:

Territory gains:

- Rheinhessen

- Principality of Isenburg

- half of Vilbel (from Kurhessen)

- Ober-Erlenbach

- Dorndiel , Radheim and Mosbach (from Bavaria)

- Share in Niederursel

Territorial losses:

- To Prussia:

- To Bavaria:

- To Kurhessen :

- Office Dorheim

- Großkrotzenburg

- Grossauheim

- Oberrodenbach

- the half of Praunheim belonging to the Grand Duchy

- Restitution of the Landgraviate of Hessen-Homburg

The occupation patents are dated July 8, 1816, but were not published until July 11, 1816.

Constitution of 1820

Due to the previous territorial gains, the Grand Duchy consisted of numerous, differently structured areas. A constitution that made the new state more uniform was urgently needed in order to integrate the different parts of the country. In addition, Art. 13 of the German Federal Act called for a “rural constitution”. The Grand Duke, Ludewig I. , resisted and is quoted as saying that estates (i.e. a parliament) "in a sovereign state [...] are unnecessary, useless and in some respects dangerous". However, the - now famous - statement does not seem to come from Ludewig I himself, but can be found in an expert report drawn up for him by the Giessen government director Ludwig Adolf von Grolmann - just like the reform process that has now been completed, it was not so much designed by the Grand Duke personally as by the civil service has been.

But in 1816 a three-person legislative commission was charged with drafting a constitution and further laws, to which Peter Joseph Floret and Karl Ludwig Wilhelm von Grolman belonged.

In March 1820, Minister of State Grolman published a provisional “ Landstands constitution ”, which was published as a grand-ducal edict and on the basis of which the first parliament was elected. On December 17, 1820, the constitution of the Grand Duchy of Hesse was enacted.

Revolution 1848

As a result of the March Revolution in 1848, the Rheinhessen liberal Heinrich von Gagern became Prime Minister of the Grand Duchy. He also represented the Rhine-Hessian areas in the Frankfurt National Assembly , of which he was temporarily president.

There were also extensive administrative reforms in 1848. So both the three provinces and all districts were dissolved and both levels were replaced by a uniform middle administrative level, government districts. With the victory of the conservative forces, the reform was reversed in the reaction era in 1852 and counties and provinces were restored. In some cases, however, this was also used to make corrections to the pre-revolutionary circle division.

War of 1866 and its consequences

After the defeat in the German War , Hessen-Darmstadt had to admit considerable territorial losses to Prussia in the peace treaty of September 3, 1866 . The territories gained by the treaty hardly made up for the loss in size. Most of them were enclaves of the states annexed by Prussia within the Grand-Ducal Hessian area. In detail these were:

- Loss of territory

- The Landgraviate of Hessen-Homburg , which only fell to the Grand Duchy at the beginning of 1866 after the sideline there had expired.

- The Biedenkopf district ,

- the district of Vöhl , including the associated exclaves Eimelrod and Höringhausen ,

- the north-western part of the district of Gießen (namely the communities: Frankenbach , Krumbach , Königsberg , Fellingshausen , Bieber , Haina , Rodheim , Waldgirmes , Naunheim and Hermannstein ),

- Rödelheim and

- the Grand Ducal Hessian part of Niederursel

- Territory gains

- The Katzenberg court (formerly Kurhessisch ),

- the office of Nauheim (formerly in Hesse),

- the Reichelsheim office (formerly Nassau ),

- Treis an der Lumda (formerly Kurhessisch),

- Dortelweil and Niedererlenbach (formerly Frankfurt ),

- Massenheim (formerly Kurhessisch),

- Harheim (formerly Nassau),

- Rumpenheim (formerly Kurhessisch) and

- two unincorporated areas:

- about 425 hectares near Mittel-Gründau (formerly part of the Hessian region) and

- a forest between Altenstadt and Bönstadt (formerly Kurhessisch).

The area losses amounted to 82 km², the area gains almost 10 km². All territorial gains - apart from Rumpenheim - were in or on the province of Upper Hesse and were added to it. Rumpenheim, on the other hand, was the only village in southern Main to belong to the Starkenburg province.

Another consequence of the peace treaty of 1866 was that all parts of the country north of the Main, i.e.

- the province of Upper Hesse and

- the places Mainz-Kastel and Mainz-Kostheim, which at that time belonged to the district of Mainz and the province of Rheinhessen (i.e. today's "AKK area" )

joined the North German Confederation .

Establishment of the Empire in 1871

With the establishment of the Empire in 1871, the Grand Duchy became a federal state of the German Empire.

Late 1918

After the First World War and the November Revolution , Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig was deposed on November 9, 1918 by the Darmstadt Workers 'and Soldiers' Council. In 1919 the Grand Duke released the Hessian officials from the oath of office they had taken on him, but never abdicated. The former Grand Duchy became the republican written People's State of Hesse .

Country

With the constitution of the Grand Duchy of Hesse introduced on December 17, 1820, Grand Duke Ludwig I ended absolutism in his state in favor of a constitutional monarchy . But the position of the Grand Duke remained strong.

The Grand Duke

The Grand Duke was the head of state who had "all the rights of state authority" and his person was "sacred and inviolable". He headed the executive branch .

| Grand duke | from | to |

The residential palace of the Grand Dukes in Darmstadt |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Ludwig I (since 1790 Landgrave Ludwig X.) |

August 14, 1806 | April 6, 1830 | |

| Ludwig II. | April 6, 1830 | June 16, 1848 | |

| Ludwig III. | June 16, 1848 | June 13, 1877 | |

| Ludwig IV. | June 13, 1877 | March 13, 1892 | |

| Ernst Ludwig | March 13, 1892 | November 9, 1918 |

executive

administration

From the beginning, the Grand Duchy faced the problem of being composed of very different parts. Even the core stock, the Landgraviate of Hessen-Darmstadt, already consisted of two different parts, the "old Hessian" and the Upper County of Katzenelnbogen . In addition, there were acquisitions through secularization and the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss 1803, through joining the Rhine Confederation in 1806 and the former French territories of Rheinhessen after the Congress of Vienna in 1816. The process of standardizing and closing the divergent structures now extended over almost the entire 19th century modernize. A certain conclusion was that, as the extremely fragmented partikular - civil law on January 1, 1900 by the same across the whole German Reich current Civil Code was replaced.

When the territories were taken over between 1803 and 1816, the Grand Duchy initially relied on the traditional structures and retained them. In the two provinces on the right bank of the Rhine, this meant that the lower state level was organized in offices , whereas in Rheinhessen the French administrative structure with cantons was retained, but was sometimes given German-language names.

The municipalities were the lowest administrative level.

Highest level

The top level of administration was the government in Darmstadt.

Upper level

The Grand Duchy initially owned the three provinces

- Starkenburg , seat of administration: Darmstadt (mainly on the right bank of the Rhine south of the Main),

- Upper Hesse , seat of administration: Gießen (mainly areas north of the Main) and

- Duchy of Westphalia (1803–1816), seat of administration: Arnsberg .

In 1816 the province of Westphalia fell to Prussia . The Grand Duchy received in exchange

- Rheinhessen , seat of administration: Mainz (mainly areas on the left bank of the Rhine).

Starkenburg and most of Rheinhessen were separated by the Rhine without there being any fixed river crossing at all. The first permanent bridge over the Rhine was the (today so called) Mainzer Südbrücke , which went into operation in 1862 as part of the Mainz – Darmstadt – Aschaffenburg railway .

Foreign territory lay between the provinces of Upper Hesse and Starkenburg, initially the Electorate of Hesse and the Free City of Frankfurt , and from 1866 Prussia . This national segmentation also influenced the economic development of the Grand Duchy.

As a result of the revolution of 1848 , on July 31, 1848, the provinces and counties were given up in favor of the establishment of eleven administrative districts and the middle level was formed exclusively by regional councils. This reform was fundamentally reversed in the reaction time after the revolution on August 1, 1852, and the previous division into provinces was restored. This structure of the state administrative division lasted until the end of the Grand Duchy and beyond.

Lower level

1806 to 1821

The historically traditional offices continued to exist in the provinces of Upper Hesse and Starkenburg. They were a level between the municipalities and the sovereignty . The functions of administration and jurisdiction were not separated here. The office was headed by a bailiff who was appointed by the rulers.

The offices had completely different sizes and shapes. In addition, some of them were still riddled with civil rights, so-called “sovereign lands”. There the state did not even have full sovereignty and was therefore anxious to redeem these rights. In contrast, the areas that were directly under the state were referred to as "Dominiallande".

Administrative reform from 1820 to 1822

In the provinces of Starkenburg and Upper Hesse, a comprehensive administrative reform was carried out from 1820, in which the former offices were dissolved. Most of this happened in 1821, in some territorial territories with a delay until 1823. With this reform, jurisdiction and administration were separated at the lower level. For the previously perceived in the offices of management tasks District districts created for the first-instance jurisdiction district courts .

In the province of Rheinhessen, the cantons from the French administrative structure were initially retained as the judicial districts of the justice of the peace . Otherwise - unlike in the other two provinces - there was no level between the provincial government and the mayor's offices .

Administrative reform 1832/1835

Even after the reform of 1821, the administrative structure was still quite small and two intermediate levels (provincial and administrative districts) between the government and the municipalities were an excessive amount of bureaucracy for a relatively small state like the Grand Duchy. In 1832 there was a further reform in the two provinces on the right bank of the Rhine and in 1835 in Rheinhessen: In principle, the provincial governments and district districts were abolished and replaced by districts . However, the system had a number of exceptions:

- From a factual point of view, a number of tasks remained within the responsibility of the respective province (police, recruitment and supervision of the foundation system and the churches). Since there was no longer a provincial government, these tasks were carried out by the district councilors of the previous provincial capitals Darmstadt and Gießen (and from 1835 also Mainz), who then acted under the title of "provincial commissioner". In 1860 they were named "Provincial Direction".

- The already arranged incorporation of the exclaves Vöhl into the district of Biedenkopf and Wimpfen into the district of Lindenfels was in fact not carried out. They each received a district administrator who had the rank of district councilor.

- Six predominantly civil district districts remained, even if the districts of Hungen and Schlitz were dissolved a few years later.

As a rule, several districts were combined into one district during the reform of 1832.

The differently structured administration of Rheinhessen, which was still shaped by the French tradition, remained untouched for the time being, but followed three years later, in 1835. For the first time, the entire Grand Duchy had a uniformly structured administration at the lower level.

Revolution 1848

As a result of the revolution of 1848 , on July 31, 1848, the provinces and counties were given up in favor of the establishment of eleven administrative districts and the middle level was formed exclusively by these regional councils. The remaining sovereign rights of the class lords were finally eliminated. The approaches begun in 1832/1835 were consequently brought to an end and the extensive exceptions in favor of a uniform and clearly structured three-tier administration (state government / regional councils / cities and municipalities) were eliminated. In Rheinhessen there was initially only one administrative district, which was subsequently divided again on May 14, 1850, into an administrative district of Mainz and an administrative district of Worms . The boundaries of these districts corresponded to those of the Mainz and Alzey district courts created in 1836 .

These ten (later eleven) administrative districts were:

- Alsfeld

- Biedenkopf

- Darmstadt

- The castle

- Erbach

- Friedberg

- to water

- Heppenheim

- Mainz

- Nidda

- Worms (from 1850)

The administrative districts had colleges at their head and there was an elected district council, an important element of self-government and the flow of revolutionary demands.

From 1852

This reform was fundamentally reversed in the reaction time after the revolution on August 1, 1852, the previous division into provinces was restored and 26 districts were created nationwide. The boundaries of the districts were redrawn and were only partially based on the boundaries before 1848. The self-governing element was retained with district councils, even if they were also restricted in terms of their opportunities to participate.

However, he retained the rights of the court lords and landlords that had fallen into the hands of the state in the course of the revolution, and did not reconstitute their district councils, but included them in state circles.

This state administrative structure, created in 1852, in principle lasted until the end of the Grand Duchy. Due to the loss and gain of territory as a result of the war in 1866 and the district reform in 1874, the number of districts changed again. During the reform of 1874, the internal structures of the districts were aligned with those of the Prussian district order of 1872, a district committee took the lead and district councils replaced the previous function of the district councils. The new version of the district regulations in 1911 did not bring about any significant changes.

military

Hesse-Darmstadt already had a standing army in the days of the landgrave. This was retained and expanded in the Grand Duchy. In 1866/1871 their units were incorporated into the Prussian army .

The estates

First chamber

The constitution of the Grand Duchy of Hesse from 1820 provided for a two-chamber system: the first chamber consisted of the princes of the ruling house, the heads of noble families, the hereditary marshal - in Hesse this was the respective senior of the Riedesel family Freiherren zu Eisenbach since 1432 - the local competent Roman Catholic bishop, i.e. usually the Bishop of Mainz , a clergyman of the Evangelical Church in Hesse who has been raised to the office of prelate by the Grand Duke for life , the Chancellor of the State University or his deputy, and up to ten citizens, whom the Grand Duke granted a seat in the Chamber because of his special merits. The prerequisite for being able to take the seat in the first chamber was the completion of the 25th year of life.

Second chamber

The second chamber consisted of elected representatives. The electoral law has been changed several times over the years. An important step in the course of the March Revolution was that in October 1850 a three-class suffrage was introduced based on the Prussian model, which changed the electoral system in favor of the upper bourgeoisie. In the course of almost a century, in which the Grand Duchy existed as a constitutional state, there was a tendency towards bourgeois electoral law and - in the last decades of its existence - a move away from census suffrage .

Judiciary

Jurisprudence

Separation of powers

The separation of jurisdiction from administration dragged on in the Landgraviate of Hessen-Darmstadt and then in the Grand Duchy for a period of almost 100 years. It began with the establishment of a higher appeal court in Darmstadt , independent of the administration, in 1747 .

In the next step, with the organizational edict of October 12, 1803, court courts were created as independent courts at the level of the middle instance in Darmstadt and Gießen .

Another step - and the one that was decisive in its broad impact - took place in 1821 when the offices were dissolved. The administrative tasks previously performed by them were transferred to the newly established district councils and for the tasks of first instance jurisdiction that they had previously performed to the newly established district courts .

In the province of Rheinhessen, the separation of jurisdiction and administration existed from the beginning, since the province, as a former French territory, brought with it and also retained far more progressive institutions for the administration of justice. Here the jurisdiction of the first instance was incumbent on the justices of the peace and the district court of Mainz , which also worked as a second instance for the peace courts.

The division of the Grand Ducal Hessian Ministry of the Interior and Justice into a Ministry of the Interior and a Ministry of Justice in 1848 can be seen as the last step in this development . As a result of the revolution, it was also due to the fact that this year the judges were abolished.

Judicial districts

During the reform of 1821 in the Grand Duchy on the right bank of the Rhine, one or two regional courts were set up for each district. Their judicial districts changed in the following period mainly because patrimonial judges ceded their rights to the state. The subsequent changes to the boundaries of the areas of responsibility of the administrative districts (administrative districts, districts, regional councils), on the other hand, had little effect on the composition of the judicial districts. After the re-establishment of the pre-revolutionary administrative organization in principle in 1852, which, however, brought about further changes in the administrative jurisdiction limits, the difference to the judicial districts had become so great that the state saw itself compelled to clear it up comprehensively in 1853: the judicial districts became large revised.

In Rheinhessen, on the other hand, the peace courts inherited from French times, each of whose district was a canton , were retained. In addition, there was initially a district court in Mainz that covered the entire province. In 1836 a second judicial district was split off and a second district court was opened in Alzey . In 1852 they were renamed "District Courts".

Reform 1879

In 1877 the Courts Constitution Act came into effect nationwide. It was implemented in the Grand Duchy of Hesse in 1879. The court constitution was now largely shaped by imperial law.

The local courts remained in place as they are unique in Germany today . The facility was even extended to the entire state of Hesse after 1945 .

Substantive law

civil right

The Grand Duchy was characterized by a fragmented legal division. Here, the applied Common Law , but in most parts of territories of particular law superimposed. The only exception was the area in which - even after the transition from France to the Grand Duchy - French law applied. In detail that was

- French law:

- Province of Rheinhessen , including Mainz-Kastel on the right bank of the Rhine and Kühkopf , which became part of the right bank of the Rhine when the Rhine was straightened in 1829 . The Civil Code was introduced in 1804, which later belonged to Rheinhessen, and was valid in the original French-language text, but there were "official" translations.

- Common law without superimposition by a particular law:

- The parts of the province of Upper Hesse that fell from the Marburg inheritance to Hesse-Darmstadt.

- The offices of Gießen , Busecker Tal , Allendorf , Homberg an der Ohm , Burg-Gemünden , Alsfeld , Grebenau , Ulrichstein , Butzbach and Rosbach .

- The Hessian part of the Hüttenberg and Philippseck offices .

- Friedberg .

- Ockstadt and Oberstrassheimer Hof .

- Fränkisch-Crumbach , Georgenhausen , Bobstadt , Finkenhof and most of the Umstadt office , all in the Starkenburg province. In the remaining parts of the Umstadt office, Electoral Palatinate law was in effect.

- City and official custom of Grünberg

- Riedesel's ordinances

- Jurisdiction

- Schlitzer regulations

-

Hessian law in the following areas acquired in 1866:

- Katzenberg district with the localities

- Formerly the Hessian exclave Treis an der Lumda

-

Solmser Landrecht applied in large parts of the southern part of the province of Upper Hesse and the former Hanau and Isenburg areas of the Starkenburg province. In addition, the Solms land law applied to different extents and in combination with other particular law:

- Solmser Landrecht, overlaid by Hessian law until 1866 in:

- Friedberger Police Regulations and subsidiary Solms Land Law

- Individual matters of the Solms land law were valid in the former Stolberg areas

- Nassau law and title 28 of the Solms land law (matrimonial property law) in the former Nassau office of Reichelsheim acquired in 1866

- Nassau law, Mainz land law and title 28 of the Solms land law (matrimonial property law) in the former Nassau district of Haarheim (today: Frankfurt-Harheim ) acquired in 1866

- Land law of the Upper County of Katzenelnbogen

- Erbacher law

- Mainz Land Law

- Palatinate Land Law , in some areas - especially the former Lampertheim Office - only individual parts of the Electoral Palatinate Land Law.

-

Frankfurt law in the areas of the former Free City of Frankfurt acquired by the peace treaty of September 3, 1866 , namely the villages

- Dortelweil and

-

Nieder-Erlenbach

The Frankfurt Reformation and, in several stages, the Solms land law and common law were applicable here .

-

Wimpfen town charter in the version of 1775

- City of Wimpfen

- Wimpfen im Thal

- Hohenstadt

- Helmhof

- Butzbach town charter from 1578 in the town of Butzbach and its district .

- Württemberg land law from 1555 in the version from 1610 for the Hessian subjects and their properties in Kürnbach

This legal fragmentation was predestined to be simplified and harmonized. From 1836 to 1853 there were intensive discussions about the reform and standardization of civil law , a discussion that even led to a discussion in the estates. The stipulation was Art. 103 of the constitution of 1820. The deliberations took place in four successive steps:

- Personal law: published in 1842, revised in 1844 (certification of civil status, marriage law , parent / child relationship, guardianship and curator ),

- Property law : published in 1845, revised in 1851,

- Law of inheritance : published in 1845 and

- Law of Obligations : Published in two parts in 1853.

The publications were made by ministerial decree. But only personal law made it into the state estates for advice. On the one hand, concerns about the project came from Rheinhessen, where those applying the law definitely wanted to adhere to the modern Civil Code. But resistance also came from those who feared that a grand-ducal-Hessian civil law could hinder the much larger cast of a codification that encompasses all of Germany . The matter came to nothing after 1853 and the small, traditional law was valid in the Grand Duchy until the introduction of the nationwide codifications, in particular the Civil Code on January 1, 1900.

Criminal law

In the Grand Duchy of Hesse, the criminal law courts continued to apply the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina ("Embarrassing Neck Court Order") from the reign of Emperor Charles V from 1532 when it came into being. In stark contrast to this, the modern Code pénal of 1810 applied in the French-influenced Rhine Province when it was incorporated into the Grand Duchy in 1816. These differences within the same state could hardly be conveyed. First consequence was the order under Article 103 of the Constitution of 1820:. "For all the Grand Duchy to a ... Criminal Code ... be introduced" But it took: It was only in 1839, the Ministry was able to present the Estates a draft. Instrumental in were Justin von Linde and Moritz Breidenbach . This draft finally resulted in the penal code of 1841, which came into force on April 1, 1842. The death penalty - also compared to the Code pénal - was further reduced, corporal punishment and declarations of dishonor as punishment were completely waived. The focus was now on prison sentences . The law was so modern and up-to-date that it was adopted by neighboring states: in 1849 by the Duchy of Nassau (with the complete abolition of the death penalty), from 1857 in the Free City of Frankfurt and in 1859 in the Landgraviate of Hesse-Homburg (including the Oberamt Meisenheim ). This criminal law was then replaced by the penal code for the German Reich , enacted on May 15, 1871 and entered into force on January 1, 1872.

Procedural law

Civil litigation

The Grand Duchy only received uniform civil procedural law with the corresponding Imperial Law of 1877. Until then, civil proceedings on the left bank of the Rhine, in Starkenburg, were determined by French law, on the right bank of the Rhine, in Upper Hesse and Starkenburg, by the Hessian procedural rules of May 2, 1724. Although Art. 103 of the constitution of 1820 contained the mandate to create a uniform procedural order for the entire state, this never came about: The law enforcement officers on the left bank of the Rhine did not want to give up their progressive French civil procedural law, so much progress went too far for the Hessians on the right bank of the Rhine. Despite several drafts, a compromise never came about.

Criminal trial

- Right bank of the Rhine

The Criminal Procedure Law was based on the right bank of embarrassment Procedure Code of 1726. After that, the process was largely written off. The verdict was made by the provincial government, which had to obtain permission from the sovereign in the event of severe corporal punishment or the death penalty. By the end of the 18th century this had developed into a purely secret inquisition process, which made it very difficult for the accused to defend himself .

In 1822, on the right bank of the Rhine, the "embarrassing courts" that had been responsible up until then were repealed and the criminal senates of the court courts became responsible.

In 1865, the two provinces on the right bank of the Rhine were given a new law on criminal procedure, which, however, fell far short of the standards that had been in effect in Rheinhessen since 1808. The procedure at the regional courts was still in writing.

- Left of the Rhine

On the left bank of the Rhine, however, modern French law was applied again. The French criminal procedural law, the Code d'instruction criminelle of 1808, applied. Oralism , publicity and immediacy of the main proceedings, the free assessment of evidence and there were jury courts applied . Depending on the severity of the offense, which the Code pénal divided into different classes, the police court under the direction of the local justice of the peace was responsible for violations , the breeding police court for offenses - that was the Mainz district court for all of Rheinhessen - and the assise (jury court) for crimes . The Assise consisted of the President of the Mainz District Court, four other judges from this court and twelve jurors. The lay judges decided in a first part of the judgment on questions of fact, the judgment itself then only passed the five lawyers involved.

State symbols

coat of arms

The coat of arms introduced in 1808 was replaced by a grand ducal decree of December 9, 1902. The shield is split twice and divided twice. The heart shield shows the Hessian lion armed with a sword . From (heraldic) top right to bottom left the shield shows nine fields for the following former, now incorporated gentlemen :

- Landgraviate of Hesse

- Imperial Principality of Mainz

- Imperial Principality of Worms

- Goat Grove County

- Small state coat of arms of the Grand Duchy of Hesse

- County Katzenelnbogen

- Principality of Isenburg

- County of Hanau

- County of Nidda

The five spangle helmets (also heraldically from the right) carry the helmet decorations to the 4th, 2nd, 1st, 6th and 8th field. Two crowned lions serve as shield holders.

The Grand Ducal Small State Coat of Arms consists of the shield called field 5, which is also held by two lions. The following medals hang down from the golden ornaments : The Grand Ducal Hessian Order of Ludwig with an eight-pointed, black, red-bordered and gold-lined cross. This was donated on August 25, 1807 by Grand Duke Ludwig von Hessen-Darmstadt. The award of the Grand Cross was restricted to princely persons and the highest dignitaries who were leading to the title “ Excellence ”. Next to it is the Grand Ducal Hessian Order of the Golden Lion . Finally, the Grand Duke of Hesse Philip Orden , who on 1 May 1840 by Grand Duke Ludwig II. "The Magnanimous Merit Philip" was donated in memory of the 1509 ruling until 1567 ancestor of Hesse-Darmstadt. The order could be awarded to civil and military persons as a reward for special merits. The purple canopy covering everything is adorned with a gem-set circlet and wears a royal crown .

Prince anthem

The prince's hymn, the melody of which corresponded to that of God Save the Queen or Heil dir in the wreath , was under the last Grand Duke - the text naturally had to be adapted every time the regent changed his government and name:

Heil our prince, Heil, Heil Hessens prince, Heil

Ernst Ludwig Heil!

Lord God, we praise you, Lord God, we implore you:

Bless him for and for

Ernst Ludwig Heil!

society

Noblemen

The mediatized rulers enjoyed considerable special rights due to the Rhine Confederation Act of 1806 and the final protocol of the Congress of Vienna of 1815 and in many cases continued to exercise sovereign rights in the areas they had previously ruled. Of course, this collided with the state's right to the monopoly of force . The relationship was therefore regulated in several legal acts, both generally valid and bilateral agreements between individual professional lords and the state. The last sovereign rights of the noblemen were not removed in the Grand Duchy until 1858. However, they retained their special social position until the end of the monarchy in 1918.

Legal Regulations

The conditions of the noblemen in the Grand Duchy of Hesse were determined by a series of legal regulations. In addition to the Rhine Confederation Act and the final protocol of the Vienna Congress, these were:

- Declaration on the constitutional relationships of the rulers of the Grand Duchy of August 1, 1807

- Addendum [to the aforementioned declaration] by ordinance of June 20, 1808

- Edict, the civil legal relationships in the Grand Duchy of Hesse from March 27, 1820

- Constitution of the Grand Duchy of Hesse from December 17th

- Law of August 3, 1848, relating to the conditions of civil servants and noble court lords

- Law of July 18, 1858, concerning the constitutional relationships of the rulers of the Grand Duchy

In addition, there were agreements between individual noblemen and the state. These include:

- Declaration concerning the constitutional relationships of Baron Riedesel zu Eisenbach from July 13, 1827

Noblemen

The rulers with stately property in the Grand Duchy of Hesse were:

- The princes and counts of Isenburg with the lines Isenburg-Meerholz , Ysenburg-Büdingen and Ysenburg-Wächtersbach .

- The princes and counts of Solms with the princely lines of Solms-Braunfels and Solms-Lich and the counts of Solms-Laubach , Solms-Rödelheim and Solms-Wildenfels . This area had 23,000 inhabitants.

- The princes of Löwenstein-Wertheim . Their area comprised 8,231 inhabitants.

- The Counts of Erbach with the lines Erbach-Erbach , Erbach-Fürstenau and Erbach-Schönberg .

- The Counts of Stolberg-Wernigerode with an area that comprised 10,013 inhabitants.

- The Count of Leiningen-Westerburg with an area that included 74 residents.

- The Counts of Görtz-Schlitz with an area that comprised 6,898 inhabitants.

- The Counts Schönborn with an area that included 1519 inhabitants.

- The barons Riedesel zu Eisenbach with an area that comprised 19,505 inhabitants.

In addition there was the knightly nobility who exercised jurisdiction ( patrimonial jurisdiction ):

- from Albini ,

- from Gemmingen ,

- from Harthausen ,

- from Frankenstein ,

- by Wambold ,

- Löw von Steinfurth ,

- from Rau to Holzhausen ,

- from Venningen ,

- from Wetzel ,

- from Lerchenfeld ,

- from Lehrbach ,

- from Eltz ,

- from Ingelheim ,

- from Breitenstein ,

- from Günderrode ,

- from pitcher ,

- Nordeck to Rabenau and

- from Seebach .

Joint institutions of the class members

The houses Isenburg and Stolberg operated a total Justizkanzlei in Büdingen , which was responsible for an area, lived in the 27,883 inhabitants.

The princely and countess lines of Solms ran a joint law firm in Hungen , which was responsible for an area of 23,000 inhabitants.

The Löwenstein-Wertheim and Erbach houses had a general law firm in Michelstadt for an area with 30,954 inhabitants.

Protocol peculiarities

The rulers were entitled to

- the acceptance of themselves and their families in the intercessory prayer . There they were to be named after the Grand Duke and his family.

- the predicate lord in all decrees issued by the authorities to the landlords.

Legal specifics

The rulers were entitled

- a special place of jurisdiction : personal matters, especially family matters of the landlords, were negotiated in the first instance before the court courts in Darmstadt and Gießen .

- the Court in its former dominions in civil matters to continue to engage in first and second instance. Criminal trials , however, were heard before the provincial courts in Darmstadt and Gießen .

- sovereign rights in forest, church and school administration as well as in the area of public safety and order .

- the exemption from military service. On the other hand, rulers were allowed to enter into foreign military service, but with grand ducal permission.

income

The income from taxes and duties, as they accrued until 1806 with the present lords, were now shared between them and the state. The Grand Duchy was entitled to:

- Government permit fees ,

- Sports , taxes and fines ordered by the higher courts or imposed by state authorities,

- the fees for the use of state infrastructure (such as: road money or bridge money ),

- Taxes,

- the saltpeter shelf ,

- the escort of Jews ,

- the new fractional tenth of all future clearings and

- the country and military supporters

The gentlemen remained:

- All possessions, including those that were imperial fiefs before the mediatization ,

- all previously received tithe, basic interest and validity ,

- all income flowing from the bondage ,

- all previous gradients from mines, forests, hunting and fishing,

- the fees previously received by the servants of the class,

- the road and bridge fees for public roads for their maintenance,

- the noble cheers and any transfer payments due from them,

- exemption from duty for the consumption of the civil household and

- the exemption from road and highway money in their rulers.

Jewish communities and the emancipation of Jews

The Jewish communities of the Grand Duchy were combined in an association called the "Israelitische Religionsgemeinschaft" (after 1918: "Landesverband der Israelitische Religionsgemeinden Hessen"). The composition of the boards of directors of the individual communities and their asset management was regulated by state regulations and supervision. The respective district office was responsible.

Samson Rothschild was the first teacher of the Jewish faith to be employed as a teacher in the Grand Duchy in 1874 at a municipal elementary school in Worms .

economy

inch

The Grand Duchy of Hesse created a customs union with Prussia in 1828 with the Prussian-Hessian Customs Union , which was merged into the German Customs Union in 1834 .

currency

With the secularization and mediatization after the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss and the Rhine Confederation, the minting rights of the abolished territories were also lost. In the Hessian area, this affected the diocese of Fulda, the princely and counts' houses of Isenburg, Solms and Erbach and Friedberg Castle. In the late summer of 1806, the last coins from Friedberg Castle were minted (even if the Grand Duchy of Hesse occupied Friedberg as early as 1804). Now only the Grand Duchy itself owned the coin rack for its territory, the only mint was Darmstadt. In Darmstadt, the coins for the Duchy of Nassau and Hesse-Homburg were also initially minted.

The Grand Duchy was a member of the South German Mint Association and minted guilder and kreuzer coins. Due to the Dresden coinage treaty, these were tied to the north German taler currency. The Grand Duchy of Hesse has therefore minted double thaler coins since 1839 and Vereinstaler coins since 1857 .

On the basis of the law of July 30, 1848, the debt repayment fund of the Grand Duchy of Hesse issued banknotes in 1848 under the name “Grundrentenscheine”. According to the Act on Basic Pension Certificates of 1848, notes with a face value of 1, 5 and 10 guilders and in 1849 with 35 and 70 guilders were issued. After forgeries of these notes had been produced and put into circulation in Philadelphia (USA), a new issue of paper money over 4.3 million guilders was brought out in 1864 (law of April 26, 1864). In addition, in 1855 the bank for southern Germany had received a concession from the Grand Ducal Hesse as a private central bank .

In 1874/75 the currency was converted to the mark throughout the empire. The Darmstadt mint now minted the new coins under the mint mark "H" until 1882, before operations were discontinued.

mass and weight

Until 1818 there were a large number of different weights and measures in the various parts of the country. There were 40 different cubits and several hundred different rods . This resulted in just as many different surface dimensions. In some cases, different weight and measurement systems applied to different goods or shops, for example for bakers and butchers.

Christian Eckhardt was commissioned to design the nationwide standardization of the systems. The new system came into effect on July 1, 1818. However, instead of introducing the modern, French, metric system that had already been in place in the province of Rheinhessen when it belonged to France, the parties involved decided on a compromise. This was mainly due to the concern that the population would not follow the reform in everyday life. There were also concerns as to whether the 10-digit jumps in the decimal system would not be too far apart in daily practice. The compromise was as follows: feet and inches were retained, but the foot was defined in such a way that it was exactly ¼ meter , i.e. 25 cm. This foot was divided into 12 inches, about ½ inch was about one centimeter. All other dimensions and weights - as in the metric system - were attached to it:

- 2.5 inch³ = 15.625 cubic inches was the basic unit for the measure of capacity

- 1 cubic inch of water thus weighed 15.625 g = 1 loth

Exceptions to this general system continued to exist for pharmacies, precious metals and jewels.

The system was implemented through a number of legal provisions:

- The ordinance on the new dimensions and weights in the Grand Duchy of Hesse of December 10, 1819 laid down the length, area and hollow dimensions as well as the weights and constituted the calibration administration in the Grand Duchy.

- A series of technical regulations followed.

- Further regulations were added over time. They regulated details or questions that had arisen in practical application.

In practice, the new system - in spite of its compromise character - was slow to establish itself and the authorities had to make further concessions. With the law concerning the application of the new system of measurements and weights of June 3, 1821 , private individuals who did not engage in any trade or trade were given the option to use any system of measurements (including the traditional units).

On August 17, 1868, the North German Confederation published a new order of measurements and weights, which came into force on January 1, 1872 and introduced the metric system. The Grand Duchy only belonged to the North German Confederation with its province of Upper Hesse. To prevent that after 1 January 1872 the country two different systems of measurement were considered, this new system with the was law, the introduction of weights and measures regulations adopted for the North German Confederation in not belonging to the North German Confederation parts of the Grand Duchy relating to the whole country extended.

railroad

The first private initiatives to build a railway network, which provided for the Frankfurt – Darmstadt – Heidelberg lines and a branch line to Mainz, failed in 1838 because the company that was founded for this purpose could not raise the capital. The state refused to join the project. Already here it becomes clear, as in the following, that the Grand Duchy did not actually operate a stringent railway policy, but later only helped with individual projects or even acted as a railway company itself without pursuing a comprehensive concept.

While the province of Starkenburg received a central railway connection with the Main-Neckar-Bahn quite early and the province of Upper Hesse was opened up at least at the edge by the Main-Weser-Bahn - the Grand Duchy held shares in both railways and they were operated as condominal railways - the railway was built for the third province, Rheinhessen , made by the private Hessische Ludwigsbahn , which developed into one of the largest German private railways. It maintained a dense network of routes in the provinces of Rheinhessen, Starkenburg and beyond. From 1853, France was connected to the Grand Duchy's rail network via the main line Mainz – Worms (–Ludwigshafen), which promoted the Grand Duchy's export economy (→ Jambon de Mayence ). The further development of the province of Upper Hesse by the railways was carried out by the Grand Ducal Hessian State Railways . All of these railways - the Ludwigsbahn had been nationalized - were incorporated into the Prussian-Hessian Railway Community in 1897 , the management of which was based in Mainz.

Companies

A number of world-famous companies were formed in the Grand Duchy of Hesse, supported by the Grand Ducal Chamber of Commerce , among others . Main areas of economic activity were Darmstadt (e.g. E. Merck ) and Mainz (e.g. Werner & Mertz ( Erdal ), the Kupferberg sparkling wine producer , various publishers, including the Philipp von Zabern publishing house ). Due to its roots in the electoral luxury goods production, Mainz was a leader in the manufacture of varnishes and varnishes (Lackfabrik Ludwig Marx) as well as fine leather ( Mayer-Michel-Deninger ) and the manufacture of luxury furniture and parquet ( Bembé ). Worms was also known for its leather production, "Offenbacher Lederwaren" are still a household name today. One of the most important branches of industry in the country was tobacco and cigar production, which operated around 200 factories. Friedrich Koch had intensive business relationships all over the world and from Oppenheim supplied well-known pharmaceutical companies with quinine. Acetic acid, acetic acid salts and methyl preparations as well as railway and tram cars were delivered from Mombach by the Verein für Chemische Industrie, now Prefere Paraform , from the Waggon factory Gebrüder Gastell . Aniline and alizarin dyes were produced in Offenbach and Worms produced water glass chemistry . In addition, the state also ran companies such as the Grand Ducal Hessian State Lottery .

Pharmacy

Culture

architecture

Georg Moller (1784-1852), a leading architect and urban planner was 1810 Oberbaurat and court architect of the Grand Duchy and built a number of public buildings: The St. Louis Church (the first post- Reformation Roman Catholic religious building Darmstadt), the State Theater , Luisenplatz with Ludwig column, the mausoleum on the Rosenhöhe and the Masonic Lodge - today's "Moller House". Outside the state capital, he built the city theater of the provincial capital Mainz in the Grand Duchy and restored Biedenkopf Castle .

Monument protection

Georg Moller is among others the rescue of the Carolingian gate hall in Lorsch to thank for today by the UNESCO recognized World Heritage Site . In 1818 he persuaded Grand Duke Ludewig to issue the first monument protection ordinance.

With the law on monument protection of July 16, 1902 , the Grand Duchy created Germany's first modern, codified monument protection law .

Art Nouveau

Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig was a great patron of the visual arts and - in contrast to most of his peers, such as Kaiser Wilhelm II. , Also modern art, especially Art Nouveau . As the grandson of Queen Victoria , he had familiarized himself with the Arts and Crafts Movement on visits to England . In 1899 he appointed seven young artists who formed an artist colony in Darmstadt . He had a studio building built on Mathildenhöhe by the architect Joseph Maria Olbrich , and the artists also had the opportunity to build their own houses. Besides Olbrich these were u. a. Peter Behrens , Hans Christiansen and Ludwig Habich . Between 1901 and 1914, four exhibitions on Art Nouveau art took place on the Mathildenhöhe. In Bad Nauheim , a unique ensemble of spa facilities was created - mainly by these artists: Sprudelhof , drinking spa, bathing houses, parks and the machine center plus laundry. Since this ensemble is still largely preserved in its details, it shapes the cityscape and makes it an extraordinary total work of art from around 1910.

Literature and language

The first works by Georg Büchner stem from the resistance against the reactionary “System du Thil ” .

The fact that Hessen-Darmstadt used different spelling rules than the neighboring states of Prussia and Bavaria until the beginning of the 20th century has a lasting effect to this day . This different spelling also resulted in a different spelling with hyphen for compound place names in the Grand Duchy. This shows that they belonged to Hessen-Darmstadt to this day. In Prussia, on January 1, 1903, the Prussian Ministry of Spiritual, Educational and Medical Affairs introduced the newly standardized spelling for all Prussian authorities. Since the rules of the Prussian State Railways applied in the Prussian-Hessian Railway Community, compound station names were now written without a hyphen, deviating from the spelling of the place names, e.g. B. " Bahnhof Groß Gerau " and " Groß-Gerau " or " Bahnhof Hohensülzen " and " Hohen-Sülzen ".

Hessian State Museum

The Hessian State Museum goes back to a foundation by Grand Duke Ludwig I in 1820, who donated his art and natural objects collection to the state. The collection had been continuously built up by the Landgraves of Hessen-Darmstadt since the 17th century and was able to be expanded significantly in the following years through acquisitions and donations. Initially housed in the castle, a separate building was therefore increasingly required. In 1897, at the instigation of Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig, the contract was awarded to the architect Alfred Messel , who had made a name for himself in Berlin with ideas for planning an ideal museum . The museum could be handed over to its purpose in 1906.

Colleges

The Ludwigs-Universität (Latinized "Ludoviciana") named after its founder was taken over from the holdings of the former Landgraviate of Hessen-Darmstadt and was now a state university.

In 1877, the Darmstadt Polytechnic School was awarded the title of Darmstadt Technical University , making it the second university in the country (today: Darmstadt Technical University ). In 1899 she was granted the right to award doctorates .

See also

literature

in alphabetical order by authors / editors

- Ulrich Brand (editor-in-chief): Ordinances and legal texts on measures and weights in the Grand Duchy of Hessen-Darmstadt. 1817–1870 = Bad Emser booklets on measurements and weights 92 = Excerpts from Friedrich Wilhelm Grimm: Complete presentation of the measurement and weight system in the Grand Duchy of Hesse […]. Darmstadt 1840 and some additional texts up to 1870 . Association for History, Monument and Landscape Conservation eV Bad Ems, Bad Ems o. J. ISSN 1436-4603

- L. Ewald: Contributions to regional studies . In: Grand Ducal Central Office for State Statistics (ed.): Contributions to the statistics of the Grand Duchy of Hesse . Jonghaus, Darmstadt 1862.

- Eckhart G. Franz : Introduction . In: Georg Ruppel and Karin Müller: Historical place directory for the area of the former Grand Duchy and People's State of Hesse with evidence of district and court affiliation from 1820 to the changes in the course of the municipal territorial reform = Darmstädter Archivschriften 2. Historical Association for Hesse. Darmstadt 1976

- Eckhart G. Franz , Peter Fleck, Fritz Kallenberg: Grand Duchy of Hesse (1800) 1806–1918 . In: Walter Heinemeyer , Helmut Berding , Peter Moraw , Hans Philippi (ed.): Handbook of Hessian History . Volume 4.2: Hesse in the German Confederation and in the New German Empire (1806) 1815–1945. The Hessian states until 1945 = publications of the historical commission for Hesse 63. Elwert. Marburg 2003. ISBN 3-7708-1238-7

- Hessian State Office for Historical Regional Studies (ed.): Historical Atlas of Hessen . Marburg 1960-1978.

- Thomas Lange: Hessen-Darmstadt's contribution to today's Hessen = Hessen. Unity from diversity, 3rd 2nd edition. Hessian State Center for Political Education , Wiesbaden 1998. ISBN 978-3-927127-12-8

- Rainer Polley : Law and Constitution . In: Winfried Speitkamp (ed.): Population, Economy and State in Hessen 1806–1945 = Publications of the Historical Commission for Hesse 63.1 = Handbook of Hessian History 1. Marburg 2010. ISBN 978-3-942225-01-4 , Pp. 335-371.

- Ulrich Reuling : Administrative division 1821–1955. With an appendix on the administrative area reform in Hesse 1968–1981 . In: Fred Schwind (ed.): Historical Atlas of Hessen. Text and explanatory volume . Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1984. ISBN 3-9212-5495-7

- Helmut Schmahl: Planted but not uprooted: The emigration from Hessen-Darmstadt (province of Rheinhessen) to Wisconsin in the 19th century. Frankfurt am Main (inter alia) 2000 (Mainz Studies on Modern History, 1)

- Arthur Benno Schmidt : The historical foundations of civil law in the Grand Duchy of Hesse . Curt von Münchow, Giessen 1893.

- Georg Wilhelm Justin Wagner : General statistics of the Grand Duchy of Hesse , Darmstadt, CW Leske, 1831. ( Volume 4 at Hathi Trust, digital library )

Web links

- The Grand Duchy of Hesse 1806–1918

- Constitution for the Grand Duchy of Hesse dated December 17, 1820 on Wikisource

- Grand Duchy of Hesse (counties and municipalities) 1910

- Illustration of the flags of Hessen-Darmstadt

- Maps of Hesse 1817–1918

- Statistical and historical information about the Grand Duchy of Hesse at HGIS

- Residential places in the Grand Duchy of Hesse , Darmstadt 1877

Remarks

- ↑ The Principality of Sayn-Wittgenstein-Berleburg had to be ceded to Prussia in 1816.

- ↑ Steinfurth and Wisselsheim (Ewald, p. 56).

- ^ Ockstadt (Schmidt, p. 24), the Oberstraßheimer Hof (Schmidt, p. 24) and Messenhausen (Ewald, p. 49).

- ↑ On the other hand, the landlords were further privileged, who were granted a tax rebate of 1 ⁄ 3 , which was based on their privileges through the Rhine Confederation Act (Franz / Fleck / Kallenberg: Großherzogtum Hessen , p. 709f.)

- ↑ The rest of Heuchelheim belonged to Stolberg-Gedern and had been in the possession of the Grand Duchy since 1806.

- ↑ Unless otherwise stated, based on the congress act of the Congress of Vienna and the implementation contract for it dated June 30, 1816.

- ↑ This happened with the exception of the Diebach court and the places Langenselbold , Lieblos , Meerholz , Spielberg , Wächtersbach and Wolferborn (Schmidt, p. 43, note 136).

- ↑ The two Hessian states had already concluded a treaty on June 29, 1816, the content of which was repeated again in the treaty of June 30, 1816 (Schmidt, p. 41, note 126).

- ↑ Only half of Petterweil, which previously belonged to Hessen-Homburg, remained with the Grand Duchy .

-

↑ These senior officials included (see: Franz / Fleck / Kallenberg: Großherzogtum Hessen , p. 703)

* August Friedrich Wilhelm Crome (1753–1833)

* Karl Christian Eigenbrodt (1769–1839)

* Claus Kröncke (1771–1843)

* Ludwig Minnigerode (1773–1839)

* Heinrich Karl Jaup (1781–1860)

* Peter Joseph Floret (1776–1836) - ↑ So also King Ludwig III. of Bavaria (see Anifer declaration ) and Prince Friedrich von Waldeck-Pyrmont . All other German monarchs abdicated.

- ↑ The two organizational edicts were published in print at the time, but then apparently never again, so that today they are only available in archives (Franz / Fleck / Kallenberg: Großherzogtum Hessen , p. 696).

- ↑ a b Title 28 of the Solms land law was customary and not fully applicable. It was changed by a "Declaratory Rescript" of September 11, 1773 (Schmidt, p. 108 and note 40).

- ↑ For the area of application within the Grand Duchy of Hesse, see the list in the article Palatinate Land Law .

- ^ Code de procédure civile of 1806.

- ↑ The two place-name signs are about 150 meters apart.

Individual evidence

- ^ Franz / Fleck / Kallenberg: Großherzogtum Hessen , p. 693 (166 square miles).

- ^ The wording is reproduced in: Schmidt, pp. 21–23.

- ^ Franz / Fleck / Kallenberg: Grand Duchy of Hesse , pp. 686–690.

- ↑ Art. 21 Rhine Confederation Act .

- ↑ Art. 24 Rhine Confederation Act .

- ↑ Ewald, p. 49.

- ↑ Ewald, p. 48.

- ↑ Ewald, p. 49.

- ↑ Ewald, p. 49.

- ↑ Ewald, p. 49.

- ↑ Ewald, p. 49.

- ↑ Ewald, p. 49.

- ↑ Ewald, p. 56.

- ↑ Ewald, p. 56.

- ↑ Ewald, p. 56.

- ↑ Ewald, p. 56.

- ↑ Ewald, p. 56.

- ↑ Ewald, p. 56.

- ^ Franz / Fleck / Kallenberg: Großherzogtum Hessen , p. 685.

- ^ Franz / Fleck / Kallenberg: Großherzogtum Hessen , p. 693 (166 square miles).

- ^ Ordinance of October 1, 1806 . In: Arnsbergisches Intellektivenblatt No. 87 of October 31, 1831, p. 282.

- ^ Edict on the abolition of the former class system of October 1, 1806 .

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 30.

- ^ Polley: Law and Constitution , p. 344.

- ^ Text (in French ) in: Schmidt, p. 30ff, note 100.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 30.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 33.

- ^ Heuchelheim, Wetteraukreis . In: LAGIS: Historical local dictionary ; As of October 16, 2018.

- ^ Text (in French) in: Schmidt, p. 34ff, note 114.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 34.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 38.

- ↑ Article 47 of the main treaty of the Congress of European Powers, Princes and Free Cities assembled in Vienna on June 9, 1815, Article 97, page 96 ( online )

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 39.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 41f.

- ^ Schmidt, p. 43, note 138.

- ^ Schmidt, p. 43, note 139.

- ↑ Exchange agreement of January 29, 1817 (Schmidt, p. 45, note 145).

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 43, note 140.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 40.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 40.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 41. Some of the initially excluded villages ( Laudenbach , Reichartshausen , Umpfenbach and Windischbuchen ) were then given over to Bavaria with an exchange agreement of January 29, 1817 (Schmidt, p. 45, note 145).

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 41, note 124.

- ^ Schmidt, p. 41.

- ↑ State Treaty of January 30, 1816 (Schmidt, p. 17f and note 61).

- ^ Schmidt, p. 41.

- ^ Schmidt, p. 41.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 44.

- ↑ On the constitutional discussion see: Uta Ziegler: Government files of the Grand Duchy of Hesse 1802–1820. Volume 6 of the sources on the reforms in the Rhine federal states, 2002, ISBN 3-486-56643-1 , p. 461 ff.

- ^ Ewald Grothe : Constitutionalism in Hessen before 1848. Three ways to the constitutional state in the Vormärz. A comparative consideration . online ; accessed on May 1, 2020.

- ^ Franz / Fleck / Kallenberg: Grand Duchy of Hessen , p. 701.

- ^ Franz / Fleck / Kallenberg: Grand Duchy of Hessen , p. 701.

- ↑ Eckhart G. Franz: Grand Ducal Hessisch ... 1806-1918. in: Uwe Schulz (Ed.): The history of Hesse. Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-8062-0332-6 , p. 184.

- ^ Constitutional charter for the Grand Duchy of Hesse December 17, 1820 . Horst Dreier . Law Faculty of the University of Würzburg . Constitutional documents from the Magna Carta to the 20th century. - Originally published: Hessisches Regierungsblatt 1820, p. 535 ff.

- ↑ Law on the organization of the administrative authorities subordinate to the Ministry of the Interior relating to July 31, 1848. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 38 of August 3, 1848, pp. 217–225.

- ^ Ordinance on the division of the Grand Duchy into circles of May 12, 1852. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 30 of May 20, 1852, pp. 224–228.

- ↑ Art. XIV, Paragraph 1, Art. XV Peace Treaty of 1866 , as well as "Description of the borders ..." in the appendix.

- ^ Schmidt, p. 46, note 152.

- ^ Art. XIV, para. 2 Peace Treaty of 1866 .

- ^ Manfred Knodt : The regents of Hessen-Darmstadt. Verlag H. L. Schlapp, 2nd edition, Darmstadt 1977, p. 149.

- ↑ Prussian and Hessian Railway Directorate in Mainz (ed.): Official Gazette of the Prussian and Hessian Railway Directorate in Mainz of March 29, 1919, No. 20. Announcement No. 225, p. 129.

- ↑ Article 4, paragraph 1 of the constitutional document for the Grand Duchy of Hesse of December 17, 1820

- ↑ Article 4, Paragraph 2 of the constitutional document for the Grand Duchy of Hesse of December 17, 1820

- ↑ See Schmidt.

- ↑ Law on the organization of the administrative authorities subordinate to the Ministry of the Interior relating to July 31, 1848. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 38 of August 3, 1848, pp. 217–225.

- ↑ Law concerning the administrative authorities subordinate to the Ministry of the Interior of April 28, 1852. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 27 of May 3, 1852, p. 201; Edict concerning the administrative authorities subordinate to the Ministry of the Interior from May 12, 1852. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 30 of May 20, 1852, pp. 221–228; Ordinance on the implementation of the organization of the administrative authorities subordinate to the Ministry of the Interior concerning May 12, 1852. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 31 of May 21, 1852, p. 229.

- ^ Ordinance on the division of the country into districts and district courts of July 14, 1821 . In: Grand Ducal Hessian Government Gazette No. 33 of July 20, 1821, p. 403ff.

- ^ Franz: Introduction , p. 9.

- ^ Edict, the organization of the government authorities, in particular concerning the provincial authorities of November 12, 1860. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 33 of November 24, 1860, pp. 341–343.

- ^ Ordinance on the formation of circles in the provinces of Starkenburg and Upper Hesse on June 6, 1832. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 74 of September 5, 1832, pp. 561-563.

- ^ Ordinance concerning the formation of circles in the province of Rheinhessen from February 4, 1835. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 6 of February 6, 1835, p. 44.

- ^ Franz: Introduction , p. 13.

- ↑ Law on the organization of the administrative authorities subordinate to the Ministry of the Interior relating to July 31, 1848. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 38 of August 3, 1848, pp. 217–225.

- ↑ Law on the circumstances of the landlords and the noble court lords of August 7, 1848. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 40 of August 9, 1848, pp. 237–241.

- ^ Franz: Introduction , p. 15.

- ↑ Law on the organization of the administrative authorities subordinate to the Ministry of the Interior relating to July 31, 1848. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 38 of August 3, 1848, pp. 217–225.

- ^ Franz: Introduction , p. 15.

- ^ Franz: Introduction , p. 15.

- ↑ Law concerning the administrative authorities subordinate to the Ministry of the Interior of April 28, 1852. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 27 of May 3, 1852, p. 201; Edict concerning the administrative authorities subordinate to the Ministry of the Interior from May 12, 1852. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 30 of May 20, 1852, pp. 221–228; Ordinance on the implementation of the organization of the administrative authorities subordinate to the Ministry of the Interior concerning May 12, 1852. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 31 of May 21, 1852, p. 229.

- ^ Franz: Introduction , p. 16.

- ↑ Law on the establishment of the district councils of February 10, 1853. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 6 of February 24, 1853, pp. 37-44.

- ↑ Art. 3 of the law concerning the circumstances of the landlords and noble court lords of August 7, 1848. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 40 of August 9, 1848, pp. 237–241.

- ↑ Law on the internal administration and representation of the districts and the provinces of June 12, 1874. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 29 of June 16, 1874, pp. 251-295.

- ^ Franz: Introduction , p. 18.

- ^ Franz: Introduction , p. 18, note 32.

- ↑ Article 52 of the constitutional document for the Grand Duchy of Hesse of December 17, 1820

- ↑ Article 54 of the constitutional document for the Grand Duchy of Hesse of December 17, 1820

- ↑ Eckhart G. Franz: Darmstadts Geschichte - Princely residence and citizen town through the centuries. Darmstadt 1980, ISBN 3-7929-0110-2 , p. 306.

- ^ Polley: Law and Constitution , p. 352.

- ^ Franz / Fleck / Kallenberg: Grand Duchy of Hessen , p. 696; Polley: Law and Constitution , p. 353, on the other hand - without any source evidence - and probably incorrectly states that the court courts were not established until 1821.

- ^ Ordinance on the division of the country into districts and district courts of July 14, 1821 . In: Grand Ducal Hessian Government Gazette No. 33 of July 20, 1821, p. 403.

- ↑ Law on the circumstances of the landlords and the noble court lords of August 7, 1848. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 40 of August 9, 1848, pp. 237–241.

-

^ Announcement,

1) the repeal of the grand ducal regional courts Großkarben and Rödelheim, and the establishment of new regional courts in Vilbel and Altenstadt, furthermore the relocation of the regional court seat from Altenschlirf to Herbstein;

2) the future composition of the district court districts in the province of Upper Hesse on October 4, 1853. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 44 of October 7, 1853, pp. 640f .; Announcement concerning:

1) the repeal of the Großkarben and Rödelheim regional courts, and the establishment of new regional courts in Darmstadt, Waldmichelbach, Vilbel and Altenstadt, and the relocation of the regional court seat from Altenschlirf to Herbstein;

2) the future composition of the city and regional court districts in the provinces of Starkenburg and Upper Hesse from April 15, 1853. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 19 of April 26, 1853, pp. 221-230. - ^ Ordinance on the division of the Starkenburg Province into two judicial districts of the first instance concerning October 4, 1836. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 46 of October 10, 1836, pp. 461–464.

- ↑ Announcement of the conversion of the designation “Gr (roßherzogliches) Kreisgericht” into the designation “Gr (roßherzogliches) Bezirksgericht” on October 24, 1853. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt no.

- ↑ Ordinance on the implementation of the German Courts Constitution Act and the Introductory Act to the Courts Constitution Act of May 14, 1879. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 15 of May 30, 1879, pp. 197f.

- ↑ § 15 Ordinance on the Implementation of the German Courts Constitution Act and the Introductory Act to the Courts Constitution Act of May 14, 1879 . In: Grand Ducal Hessian Government Gazette No. 15 of May 30, 1879, pp. 197–203 (202).

- ^ Schmidt, p. 100 and map.

- ^ Polley: Law and Constitution , p. 344f.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 100.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 100, note 6 and p. 9.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 100, note 6 and p. 9, 11.

- ^ Schmidt, p. 101.

- ^ Schmidt, p. 101.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 102.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 102f and Note 12.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 104, note 21 and p. 46.

- ^ Schmidt, p. 105, note 26 and p. 107.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 107.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 108.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 108 and note 38, p. 46 [No. 3].

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 108 and note 38, p. 46 [No. 3].

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 108f.

- ^ Schmidt, p. 109, note 43.

- ^ Schmidt, p. 109.

- ^ Schmidt, p. 109.

- ^ Schmidt, pp. 15, 17.

- ^ Schmidt, p. 109.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 110.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 111f.

- ^ Based on the "Council of August 20, 1726" of the city of Frankfurt (Schmidt, p. 112).

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 75, note 65, and p. 112.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 112.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 113.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 5, note 4, p. 75 and p. 113.

- ↑ "A civil code, a penal code and a code of procedure in legal matters are to be introduced for the whole of the Grand Duchy" .

- ^ Polley: Law and Constitution , p. 346f.

- ^ Polley: Law and Constitution , p. 359.

- ↑ Article 103 of the 1820 Constitution .

- ^ Polley: Law and Constitution , p. 359.

- ↑ Criminal Code of September 17, 1841. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 30 of October 13, 1841, pp. 409-519.

- ^ Polley: Law and Constitution , p. 359.

- ^ Polley: Law and Constitution , p. 360.

- ↑ Criminal Code for the German Empire . In: RGBl . 1871, pp. 128-203.

- ↑ Cf. on this: Thomas Kischkel: The verdicts of the Giessen Faculty of Law. Basics - History - Content . Georg Ohms, Hildesheim 2016. ISBN 978-3-487-15396-4 , p. 108 and note 563.

- ^ Polley: Law and Constitution , p. 354.

- ^ Polley: Law and Constitution , p. 361.

- ^ Polley: Law and Constitution , p. 362.

- ↑ Criminal Proceßordnung of September 13, 1865. In: Großherzoglich Hessisches Regierungsblatt No. 40 of September 16, 1865, pp. 681–790.

- ^ Polley: Law and Constitution , p. 365.

- ^ Polley: Law and Constitution , p. 363.

- ^ Polley: Law and Constitution , p. 364.

- ^ Polley: Law and Constitution , p. 364.

- ^ Polley: Law and Constitution , p. 365.

- ↑ Ulrich Becke: Frittie and Princess Sunshine. Ernst Ludwig von Hessen and bei Rhein - a torn poet. In: Festschrift. 100 years of Thanksgiving Church Bad Nauheim 1906–2006. Bad Nauheim 2006, p. 25.

- ^ Archive of the Grand Ducal Hessian laws and ordinances . Vol. 1 (1807), pp. 95-120.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 22, note 68.

- ^ Reg. Blatt February 2, 1820. P. 134ff

- ^ Constitutional charter for the Grand Duchy of Hesse December 17, 1820 . Horst Dreier . Law Faculty of the University of Würzburg . Constitutional documents from the Magna Carta to the 20th century. - Originally published: Hessisches Regierungsblatt 1820, p. 535 ff.

- ↑ Law on the Conditions of the Class Lords and Noble Court Lords of August 7, 1848 . In: Grand Duke of Hesse (ed.): Grand Ducal Hessian Government Gazette. 1848 no. 40 , p. 237–241 ( online at the information system of the Hessian state parliament [PDF; 42,9 MB ]).