History of Poland

The history of Poland encompasses developments in the territory of the Republic of Poland and the historical Polish empires from prehistory to the present. The - unwritten - prehistory of Poland includes numerous Slavic tribes, castles, settlements and grave sites. A precise ethnic allocation is uncertain. Today's ignorance about Poland's origins is a result of the lack of sources in the 10th century, which historical research calls the “ dark century ”.

The - written - history of Poland begins in the year 963, when the Polish Duke Mieszko , Latin Misaca († 992), is mentioned by Widukind von Corvey in a Latin chronicle as a capable ruler. Mieszko's voluntary acceptance of Christianity, through baptism in 966, led to the Christianization of Poland and protected the country from foreign missioning. The kingdom of Poland , recognized by the emperor and the pope and firmly established towards the end of the Piast era (960–1386), emerged from his duchy, which is said to have included a tribe of the Polans .

The so-called Dagome-iudex-Regest is an important source for establishing or recognizing a Polish state , although it is not explicitly mentioned in it. It is assumed that the entry of a monk from the years 1086/1087 describes an act of donation by the Polish Duke Mieszko I to the Apostolic See from the year 991, with which Mieszko placed his city or country under the direct protection of the Pope . At the Cracow Academy the certificate was called Oda's donation.

The Polish Church developed independently of the Imperial Church and was in direct contact with the Roman Curia . The British historian Norman Davies described the official adoption of Christianity as "the most important event in Polish history".

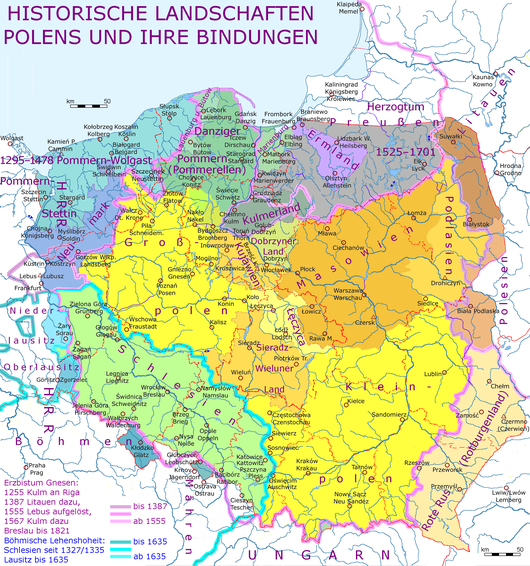

From the late Middle Ages to modern times , there was a dynastic connection with Lithuania through a personal union . From 1386, the union with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania under the ruling dynasty of the Jagiellonians (1386–1572) from there brought the rise to a major European power, their territory od morza do morza ("from sea to sea"), from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, was enough.

From 1569 the union of Poland and Lithuania was consolidated in a common state . The aristocratic republic , which existed from 1572 to 1795, manifested itself as an elective monarchy . In the 16th and 17th centuries, a high parliamentary culture with extensive nobility rights emerged there. This led to a strong identification of the nobility, the magnate (high nobility) and the Szlachta (land nobility), with the country. The increasing structural grievances caused by numerous wars with neighboring states, civil wars and uprisings by the Ukrainian Cossacks , the unwillingness to reform among those in charge, plus egoism among several electoral kings and among the nobility, weakened the Polish state. The diplomatic and military interference of the neighboring states, the Empire of Russia , Prussia and the Habsburg Monarchy , finally brought about the complete collapse of the state through three partitions in 1772, 1793 and 1795.

As a result, Poland disappeared from the maps of Europe as a sovereign state from 1795 to 1918. Characteristics of the time of division are suppressed uprisings - in the years 1830 , 1848 and 1863 - and very different developments in the three areas of division. Polish culture survived this time despite foreign oppression and its own statelessness.

After the state "rebirth" as the Second Republic after the end of the First World War in 1918, Polish history was marked by laborious state reorganization and several military conflicts with almost all neighboring states. The two dictators Hitler and Stalin agreed in the additional protocol of the German-Soviet non-aggression pact signed at the end of August 1939 that Poland should be divided up again. The attack on Poland by the Wehrmacht , the beginning of World War II , and the Soviet invasion of eastern Poland were followed by years of German and Soviet occupation . About six million Poles died in World War II. After the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht , Poland, shifted to the west, became a people's republic and part of the Eastern Bloc and a satellite state (not always more convenient for the Soviet Union) under massive Soviet influence . The revolutions of 1989 cleared the way for the Third Republic ; this became a member of NATO in 1997 and of the European Union in 2004 .

Prehistory and early history

Numerous prehistoric finds, the oldest from the Stone Age in the area of today's southern Poland , with fortifications, settlements and grave sites testify to different cultural epochs and the settlement of today's Polish territory. The assignment of the finds to a closed settlement area of the Poles is not clear. Migration movements of various peoples through the area of today's country resulted in a great ethnic diversity, in historical times one of the characteristics of the population of Poland. The British historian Norman Davies notes that prehistory is often interpreted to mean that "exclusive ownership" of an area for the benefit of only one ethnic group is derived from it. This is what happened with the area between the Oder and the Bug ; The “autochthonous school” in Poland interprets the area as the “fixed and sole home of the ancient Slavs” ( Prasłowianie ). The national Prussian historiography, however, made the area the original home of the early East Germans. Indeed, the lengthy process that gave the Slavic, Polish-speaking element a prominent position within the general population is in the dark.

Taking into account the aforementioned restrictions, it can be assumed that some Slavic tribes from the Dniester and Pripet region settled in the area between the Oder, Vistula and Baltic Sea between the 6th and 7th centuries . Their migration was triggered by the Huns storm at the beginning of the Germanic migration .

Formation of rule by the Polans

The tangible beginning of Polish history falls in the 10th century. Between 880 and 960, various West Slavic tribes grew together to form a state between the Oder and Vistula. The most important of these tribes were the Opolans , the Slenzans , the Masovians , and the Wislanes . Another tribe, the Polanen ( polanie , "field residents") is said to have established a permanent state that emerged as a duchy in the late 10th century in the region around the cities of Poznan and Gniezno . The fact that the ruling association of the Polans, whose settlement center formed an area around Gniezno, did not appear in the written sources in the 9th and 10th centuries, explained the older Polish historiography with the relative isolation of central Greater Poland . Without contact with Eastern Franconia, Bohemia, Moravia, and beyond the known trade routes, the Polans could have developed and consolidated here completely unnoticed by the outside world.

The emergence of their increasingly condensed and coherent territory took place through a planned conquest. The first traces of their violent actions can be found on the middle Warta and along the Obra , where at the beginning of the 10th century older, small castle seats from the 8th to 9th centuries of various small rulers were systematically destroyed. The local population was resettled in the Gnesen highlands , the possible home area of the Polans. Up until then, the Gnesen highlands had neither a more intensive population nor a network of castles. The original area was consolidated in the 920s and 950s through the expansion of the two castle towns of Giecz and Moraczewo . Furthermore, wooden and earth walls as well as castle chains were built on its periphery. These planned expansions required large amounts of resources and a large number of workers. Archaeological findings at this time show changes in the geographic area of settlement, in the course of which the western and southwestern regions of Greater Poland were exposed to massive destruction and depopulation, while the central area of Poznan and Gniezno experienced an internal colonization and an increase in population.

The leaders of the Polans relied on an elite, tightly managed, powerful military following. Since the 930s and 940s, luxury goods from interregional exchange have increasingly reached Wielkopolska. These were exchanged for people who were mainly in demand on the oriental and southern European slave markets. For the actual livelihood of this ruling elite, the local population had to pay for taxes and services. Due to the still underdeveloped agricultural society, it quickly reached its limits. In order to secure the loyalty of his military allegiance, the duke had to provide for and reward them regularly, for which his own territory and the population were insufficient. Slaves could only be drawn from their own population to a small extent. Therefore, raids and wars in foreign territories and the extraction of the local resources were an indispensable instrument for securing rule. This explains the rapidly increasing expansion of the Polans outside of their own core area.

960–1138: From Mieszko I on the first crisis of the Piast state

Christianization and rise of Poland

The subsequent expansion of the Polanen was directed initially to the south and southeast in the areas of Kalisz , Sieradz and Łęczyca , to the west in the area of Międzyrzecz , to the east in the area of Kruszwica and beyond to the lower Vistula . When Mieszko I took over leadership , around 960 in Gniezno, Poland entered European history as an organized state. In the west Mieszko advanced to the lower Oder until 960, where he collided with pagan Elbe Slavs and Saxon margraves, who set limits to his western expansion.

Mieszko is first mentioned in 962 or 963 as rex Misaca (King Misaca) in the Saxon history of Widukind von Corvey from around 967 in connection with two heavy military defeats against a Slavic army under the leadership of the Saxon nobleman Wichmann II . In 965 Mieszko allied himself with the Christian Duchy of Bohemia , married the Bohemian duke's daughter Dobrawa from the Przemyslid family and was baptized in 966 according to the Latin rite . He gradually implemented the Christianization of Poland . The adoption of Christianity was a power political decision. It was triggered by the incursions of the margraves on the pretext of fighting the heathen and missioning. Mieszko I was able to expand his own borders under the pretext of proselytizing and at the same time gain an advantage against the competition of inner noble families by being accepted into the Christian community of European princes. A missionary diocese was founded in Posen in 968 for the Polish ecclesiastical province . Whether this was directly subordinate to the Pope or formally to the Archdiocese of Magdeburg is disputed (→ Diocese of Posen ).

Despite the Polish prince's acceptance of the Christian faith, Wichmann, the military leader of the Slavic Wolin League , began a war against Mieszko in 967. Mieszko benefited from his alliance with Bohemia for the first time when he was able to flee Wichmann together with Pre-Semyslid cavalry troops. The margrave's sword was delivered by Mieszko to Emperor Otto . Nothing stood in the way of Mieszko's advance to Pomerania . In the period between 967 and 979 Mieszko subjugated the whole of Pomerania and Pomerania . Access to the Baltic Sea resulted in a conflict with Scandinavia. Thereupon Mieszko arranged the wedding of his daughter Świętosława with King Sven of Denmark . In 972 Mieszko successfully fended off an incursion by Margrave Hodo I from the Lausitz region . Emperor Otto I - concerned about the conditions on his eastern border - called on the opponents to rest and order during the Quedlinburg Court Day (six weeks before his death on May 7, 973). Mieszko made peace with Hodo, swore the emperor's oath of allegiance in 968 and thus established a feudal relationship with the East Franconian-German ruler.

After the death of Mieszko's first wife Dobrawa and his marriage in 978 to the daughter of the Saxon margrave Dietrich von Haldensleben , Oda von Haldensleben , there was a break between Poland and Bohemia and in 989 a war broke out in which Poland, Slovakia, Moravia, Silesia and Lesser Poland were conquered. In the east, the Chervenian castles were lost in 981 , and with them control over an important trade route with Eastern Europe . Mieszko paid homage to the underage King Otto III in 986 . in Quedlinburg and led a pagan campaign against the Elbe Slavs in his name as "Margrave of the Empire" . Mieszko thus took an active part in the further Christianization of Slavic peoples. In return, the empire supported him militarily against Bohemia. Shortly before his death, Mieszko put his country under the protection of the Pope ( Donatio Poloniæ ) in 991 , making Poland a papal fiefdom . Mieszko may have wanted to demonstrate his independence from its powerful western neighbor.

At his death in 992 Mieszko I left behind a consolidated and expanded domain that was accepted by the European nobility. An area threatened with compulsory missionary work had become a basis for the further Christianization of the Slavic world.

Political emancipation from the empire

Mieszko I. divided his empire according to Old Slavic tradition among his sons Bolesław I , Świętopełk, Lambert and Mieszko. With the support of influential magnates, Bolesław ousted his stepmother and drove her and her sons out of Poland, where she was accepted and protected by relatives in Saxony . Imperial unity was thus restored. Bolesław continued his father's policy of alliances by helping Otto III defend the Christian faith. According to the Quedlinburg Agreement of 991, he participated in the unsuccessful fight against the pagan Elbe Slavs. By integrating the Christianized peoples of the East, the emperor tried to establish a new Christian world empire under the leadership of the emperor as the secular head of Christianity. In these considerations, Poland assumed a key position within the Sclavinia . Consequently, Otto III announced. during a visit his imperial concept of the Renovatio Imperii Romanorum , which Sclavinia envisaged as an equal pillar of the empire alongside Roma, Gallia and Germania . The Archdiocese of Gniezno was established for the Slavic provinces , to which the bishoprics of Kolberg , Krakow and Breslau were subordinate. The establishment of an independent church province played an important role in the emancipation of Poland from the Roman-German Empire. Otto III. officially recognized the sovereignty of the piastic-Polish ruler. The obligation to pay tribute, which had existed since 963, was dropped. Otto III. favored the consolidation and expansion of power of the Piasts against the Czech Przemyslids, whose interests were not in line with those of the empire.

Bolesław is said to be from Otto III. had been raised to king in the act of Gniezno . This is historically controversial. What is certain is that the Pope's permission was missing. Due to the early death of Otto III. and the political resistance of the new German king and later Roman-German emperor Heinrich II. the official coronation took place as a repeat act only in 1025.

The early death of Otto III. in 1002 and the following accession to the throne of Henry II, who saw Bolesław as a Slavic vassal, fundamentally changed Poland's relations with the Empire. Bolesław came into opposition to the empire, developed his own ideas of a Christian universal empire, pursued personal expansion goals and refused any homage to Heinrich. This led to a multi-year war between Poland and the empire, at the end of which Poland was able to assert itself thanks to its already established statehood and in the Peace of Bautzen concluded a compromise peace with the emperor. Bolesław owed this to his dynastic policy, the Saxon allies in the empire and his brother-in-law King Sven of Denmark , who threatened the emperor from the north. Although he could not wrest the Mark Meissen from the emperor, in return he kept his acquisitions in the west, the Milzener Land and the Mark Lausitz, which remained with Poland until 1031. Overall, the war with the Reich led to a loss of substance internally.

The agreement reached between Poland and the Reich in Gniezno in 1000 was confirmed by Heinrich. After the peace agreement with the emperor, he received military support from the Roman-German emperor as an ally for his long-planned move to Kiev against Yaroslav to support his brother, his son-in-law Grand Duke Svjatopolk . After the successful reinstatement of the expelled prince, he bought back the Chervenian castles for Poland in 1018. After his move to Kiev, Bolesław was the most influential ruler in Central and Eastern Europe. Emperor Heinrich died in 1024. Bolesław used the resulting German interregnum by having himself crowned king a second time in 1025 (repeat act of the coronation ceremony from the year 1000). Despite the gain in prestige, the kingship could not establish itself permanently.

Bolesław intervened in the disputes of the Slavic tribes in the Nordmark and built a castle in Berlin-Köpenick on today's castle island. For the next 120 years, until the middle of the 12th century, Köpenick was the seat of a piastic vassal.

Bolesław promoted the Christian faith in Poland, since the Pope was one of the most important power-political competitors of the German emperor in the 11th century. With the successful establishment of an independent Polish ecclesiastical province and the Archdiocese of Gniezno and his coronation as the first Polish king, he promoted Polish emancipation from the empire. He was also the founder of the Polish castellan's constitution . During his reign, the politically relatively insignificant duchy of his father became a power factor in the region with spheres of influence from the Elbe to the Dnepr and from the Baltic Sea to the Danube .

Decline of power and division of inheritance

After Bolesław's death, his son Mieszko II. Lambert took over the rule. He and his German wife Richeza immediately rose to the rank of kings in order to secure themselves from the feudal rule of the Roman-German emperors. Nevertheless, he did not succeed in holding the territories conquered by his father. After only five years of reign, his empire began to disintegrate due to internal instability: This is due to a variety of factors:

- The costs imposed on the people:

- through wars,

- for building the monarchy,

- for the growing church structures

- The brothers Mieszkos, Otto and Bezprym , who fled abroad and undermined Mieszkos rule.

In 1028 and 1030 King Mieszko II undertook military campaigns against eastern parts of the East Frankish-German Empire, especially against Thuringia and the tribal duchy of Saxony , because the new emperor, Konrad II , refused to recognize him as king. Mieszko had powerful enemies in the Salian Empire and in the Kievan Rus. Several military actions carried out at the same time by Konrad and the Ruthenian Grand Duke Yaroslav, who was already one of his father's enemies, led to the loss of the Lausitz region and the Chervenian castles . This alliance strengthened the internal opposition, since Mieszko's relatives now allied with the ruler's opponents. Finally Mieszko was overthrown in 1031 and was forced to leave the land to his half-brother Bezprym and younger brother Otto, he himself fled to Bohemia.

Bezprym's rule did not last long. An uprising against the new ruler led to his assassination in 1032. His death led Mieszko II to return home after an understanding with Otto. After Emperor Konrad threatened another military intervention in Poland, an agreement was reached during the Merseburg Court Conference in 1033. Mieszko II renounced his royal dignity and shared his empire with his brother Otto and Dietrich , a grandson of Mieszkos I. Duke Otto died in the same year, and Dietrich lost his sphere of influence for unknown reasons, so that Mieszko was unified shortly before his death , on May 10, 1034, regained. After his death, Mieszko II left behind a weakened empire which, due to a lack of strong royal authority, began to erode through popular uprisings and pagan reactions. By renouncing royal honors, Poland was again dependent on the Roman-German Empire for decades from 1033 . Mieszko's son Casimir I took over the rule after his death. He too did not stay in power for long and, under pressure from the opposition, had to flee from Poland to Hungary in 1037. Between 1037 and 1039 the Polish state disintegrated. In Wielkopolska there were revolts against the church and the magnates. These had benefited from socio-political changes such as the introduction of a system similar to the tithe , while the free peasants were forced into a relationship of dependence and a relapse into paganism ensued. Individual regions became independent, including Mazovia and Pomerania.

The Bohemian duke used the lack of structure for a campaign to Poland. Greater Poland was devastated and Silesia was conquered. In addition, pagan Prussians and Pomorans were plundered. The new emperor in the empire, Heinrich III. , tried to prevent a political strengthening of Bohemia under Břetislav I and supported Casimir I militarily in 1039. With this help, Duke Casimir I came back into possession of Greater Poland and, in 1040, Lesser Poland. Krakow became the new capital of Poland. In 1041 the emperor forced the Bohemian ruler to renounce his claims against Poland, but did not return Silesia to Poland. In order to secure the border in the east, Casimir I concluded an alliance with Yaroslav of Kiev in the same year and a little later married his sister, Princess Dobroniega Maria . Yaroslav then granted him military assistance in the reconquest of Mazovia and Pomerania in 1047. Against the will of the emperor, Casimir I regained Silesia from Bohemia around 1046. After Břetislav I supported a rebellion against the emperor around 1053 and fell out of favor, he had to finally renounce Poland in 1054, which became the occasion for further Bohemian-Polish disputes. The two equally strong Slavic states weakened each other politically and militarily. Casimir rebuilt the Christian state of the Piasts after the last pagan reaction and established chivalry in Poland by giving land to warriors to provide for them .

After Kasimir's death in 1058, he was followed by his son Bolesław II . This operated a successful foreign policy. He got rid of the tribute obligation for Silesia to Bohemia. He continued his father's reconstruction work, especially in the area of church structures. The condemnation and killing of Bishop Stanislaus of Cracow under unclear circumstances, which sparked an uprising against Bolesław that led to his flight, cast a shadow over his rule . Bolesław II was followed by his younger brother Władysław I Herman . For a few years he again paid tribute to Bohemia for the possession of Silesia. At the end of his rule he came into conflict with his sons, Bolesław (III.) And Zbigniew. Under pressure from the aristocratic opposition, he had to allocate their own provinces in 1098, but retained the supremacy with its headquarters in Płock . During his reign, the first Jews came to Poland in large numbers in 1096 , seeking protection against the pogroms that broke out in many cities in Western Europe during the First Crusade . Władysław Herman died in 1102, leaving a Poland divided between his sons. Bolesław III. Schiefmund subjugated his half-brother Zbigniew in 1108 and successfully repelled a campaign by Emperor Henry V , who did not agree , in 1109 . Under his rule, Poland expanded its sphere of influence through the final submission of the pagan Pomorans to Pomerania. In Otto's escort, among other things, the first German settlers came to Pomerania as monks. Bolesław's sphere of influence extended into what is now Brandenburg . Through the establishment of the diocese of Lebus , Brandenburg remained ecclesiastically connected to the archbishopric of Gniezno until the 15th century . Towards the end of his reign he embroiled Poland in conflicts with Hungary and Bohemia. He let his daughters marry into the Scandinavian, Saxon and Ruthenian rulers. Since Bolesław III. Wanted to avoid fratricidal struggles among his four sons, he divided his empire according to Slavic custom, with the elder of the Piast family embodying the unity of the country to the outside world within the framework of the seniority principle .

1138-1295: particularism

For the next 150 years, ongoing struggles broke out for control of Krakow and the supremacy of the entire country. The kingdom broke up into several piastic duchies, which feuded for power, territory and influence. The oldest of the Piast dynasty, Władysław II , became Senior Duke of Poland with his seat in Cracow. The younger brothers ruled as junior dukes in the regions assigned to them. This weakened Poland's politico-military position in 13th century Europe. The idea of the unified Polish state lived on in the unified church organization and the tradition of the great noble families as well as in the dynastic relationship of all rulers.

East German settlement

During the expulsion of Mieszko III. the younger representatives of the dynasty prevailed in Krakow in 1177 through local magnate families. Although the Duke of Cracow retained a certain suzerainty, the Assembly of Polish Dukes and Bishops at Łęczyca in 1180 repealed the seniority principle and guaranteed the prerogatives of the clergy. The unity of Poland was not achieved; the Piast duchies continued to coexist as sovereign regions. The Seniorate Province of Lesser Poland with Krakow fell to Leszek I in 1194. In his titulature dux totius Poloniae , Leszek I was the last duke to claim suzerainty in all of Poland and tried to enforce this from 1217 in Pomerania as well. The Polish princes met in 1227 in Gąsawa, Kujawien , for a Wiec to advise against Duke Swantopolk of Pomerania and her cousin, the Piast Władysław Odonic , Duke of Greater Poland and grandson of Mieszkos III. The gathering was blown while Leszek was fleeing from Pomeranian and Greater Poland captors. His demise ultimately resulted in the complete disappearance of a central power in Poland. Except for the ecclesiastical structures of the Archdiocese of Gniezno there was no supra-regional Polish state law or other supraregional state institutions. An increased fragmentation of Polish countries began, which made it easier for the German and Bohemian princes to expand in Poland from the middle of the 13th century.

During this time there was an increased colonization of Polish areas by emigrants from the Holy Roman Empire . Until 1250 large parts of Pomerania and Silesia were populated by Germans and Flemings , who were brought into the country by local lords, such as the griffins in Pomerania and the Silesian Piasts. The Pomeranian aristocrats, as well as the Silesian princes, promised themselves primarily higher economic prosperity, better tax revenue, but above all a faster connection to the (rural) economic-urban standards of Western Europe through the new settlers. Due to the number of new settlers and the personal commitment and support of the eastern settlement by the Polish sovereigns, large parts of medieval Poland became part of the German-speaking area over the centuries and permanently lost their Slavic-Polish character. Some rulers, such as the Silesian Piasts, voluntarily opened up to Germans by filling high offices in the state and in ecclesiastical structures with Germans and marriages with princesses from German noble houses, which resulted in kinship relationships with the German aristocracy. The fact that the Griffins and the Silesian Piasts were Polish senior dukes and the most powerful sovereign princes in the first half of the 13th century also favored the eastern colonization and the spread of Germanness in Silesia and beyond the borders of Silesia. The deslawization and the corresponding Germanization took place peacefully and was not a brutal German conquest of Polish territories - however, conflicts cannot be ruled out due to the lack of consideration of the interests of the local indigenous population through the process of eastern settlement between the long-established Poles and the immigrants who were mostly not Slavic. It was not until the end of the 13th century and the beginning of the 14th century that an opposing movement began, which pushed back the cultural-economic dominance and the influence of Germanness in the core provinces of Poland (Lesser and Greater Poland) and the repolonization of large regions and many cities led.

Mongol storm of 1241

Władysław the expellee, who fled to the empire, won the favor of the emperor, who intervened militarily for him in Poland in 1157. Frederick Barbarossa forced the Polish Senior Duke Boleslaw IV. To surrender Silesia to the sons of the ousted sovereign and made him a part of his kingdom lehnspflichtig . However, Bolesław hesitated for a few years to comply with the Hohenstaufen demands and only in 1163, under the threat of a new imperial intervention, he handed Silesia over to the sons of Władysław, Bolesław the Long and Mieszko Sacrum . When this province was handed over to the descendants of Władysław, the long-lived line of the Silesian Piasts was born .

The unification of Poland through the Silesian line of the Piasts came to an abrupt end with the death of Henry the Pious . The duke lost his life in the battle against the Golden Horde in the Battle of Liegnitz , and the Duchy of Silesia disintegrated after 1241 into a number of feudal principalities that came under the influence of Bohemia after the Mongol invasion . The Mongol invasion added importance to the German colonization in the east in Poland and in other regions of Central Europe affected by it, where a considerable part of the population was either killed or driven into Mongol servitude. The Mongols, who were also called Tatars , withdrew into the Ruthenian principalities they had conquered. Until the end of the 13th century they remained a constant threat and undertook further raids towards the west, which weakened the politically fragmented Poland economically and militarily, so that the rulers of the neighboring peoples, such as the Lithuanians, but especially the Bohemians and the Germans, began. to expand their own territories on Polish territory.

The expansion of the Mark Brandenburg to the east on Polish-Piastic areas led to the loss of Lebus in 1250 and the emergence of the Neumark as a counterpart to the Altmark. Around 1250, Poland was pushed back from today's Oder border for centuries , despite attempts to recapture it under King Władysław I. Ellenlang at the beginning of the 14th century.

Help from the Teutonic Order

The Polish Duke Conrad I began to expand his sphere of influence. The Prussian area around Kulm was his war target. Expansion at the expense of its pagan neighbors was a fiasco. He lost his conquests and in turn was threatened by the awakened neighbor. Since he was also involved in conflicts with other Piast rulers, he turned his gaze to the Teutonic Order, which was expelled from Hungary in 1225 because it wanted to found its own state in Transylvania in the fight against pagan steppe peoples, the Cumans . In 1226 Konrad von Masowien asked the Teutonic Order for help and promised him the Kulmer Land as a ducal fiefdom, as a consideration and starting point for their fight against the pagans. To what extent the territories to be conquered belonged to the order according to the agreement is still unclear and has in the past led to disputes between German and Polish historians. In order to protect himself against a similar development as in Hungary, the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order, Hermann von Salza , had the possession of the Kulmer Land and all areas to be conquered by Emperor Friedrich II confirmed with the Golden Bull of Rimini in March 1226 . In addition, the order concluded the Treaty of Kruschwitz with the Duke on June 16, 1230 , which made the land freely available to him. Hundreds of years of hostility developed between the Teutonic Order of Knights in Prussia and Poland, and later also Lithuania .

1295–1386: Reunification

End of particularism

Renewed attempts at reunification were made from Poznan and Gniezno. At the end of the 13th century, Duke Przemysław II of Wielkopolska assumed leadership of the Union of Piast-Polish Duchies. Although he never came into permanent possession of the Duchy of Malopolska-Krakow , he only ruled there for about a year and, under pressure from the Bohemian King, had to leave it in 1291 for Poznan. In possession of the Krakow royal insignia and as regent of the duchies of Greater Poland and Pomerania (from 1294), he was crowned by the Polish Archbishop Jakub Świnka in Gniezno in 1295 as the fourth Polish king since Bolesław the Bold. With this symbolic act, he ended Polish particularism and, with his coronation, focused the forces of the Polish nobility and the church to regain the state unity of Poland against the German and Bohemian sovereigns. During a trip to Poznan in early February 1296, he was captured and slain in Rogoźno near Poznan by a group of noble opposition members. With him, the Piast line of Greater Poland, which was founded by Mieszko the ancients, died out in the male line. Wielkopolska and Pomerania fell to his cousin, Władysław Ellenlang, Duke of Kujawy , who defended both provinces against Bohemia until 1300. After the king's death, the Brandenburgers, together with the dukes of Glogau , Heinrich III., Appropriated some of the Warta and Netzed districts in Greater Poland. After Przemysław's death, the Bohemian King Wenceslaus II came into possession of the country with the help of the Polish Church and the German bourgeoisie living in Poland. As early as 1291 he was lord of Lesser Poland including Cracow, nine years later, in 1300, he was elevated to the status of a Polish king. To give his rule in Poland a legal impression, Wenzel married Przemysław's daughter Elisabeth Richza in 1303 . After his coronation, the Bohemian pushed his political opponent Władysław entirely out of Poland, who was forced to seek protection and help in exile in Hungary .

However, the Bohemian possession of Poland, as well as the Polish crown, was declared illegal by Pope Boniface VIII . With the death of Wenceslas III. , a Polish titular king , 1306, the old Czech family of the Přemyslids died out in the male line entitled to inheritance and the first German dynasty, the House of Luxemburg , came to power in Bohemia. Only after the assassination of the Bohemian ruler was the rule of the Piasts secured for the time being and Władysław Ellenlang was recognized as the new ruler. Under his rule Poland was reunited in a somewhat reduced form.

Conflicts over the western territories

Władysław I. Ellenlang returned from exile with Hungarian help and took control of large parts of Poland (Lesser Poland, Central Poland with the main castles Sieradz and Łęczyca, Kujawia and Dobrin) in the years 1305–1306. In Pomerania and Danzig he was unable to assert himself against the Brandenburgers and called on the Teutonic Knights Order for help. Because the king did not pay the agreed war debts, the Teutonic Knights kept Danzig, a procedure that was quite common at the time (see takeover of Danzig by the Teutonic Order ). The order also acquired Pomeranian and, in view of the failed crusades and the dissolution of the Knights Templar , relocated the Grand Master's seat from Venice to Marienburg in the Vistula Delta . This started a conflict with the Christian state of Poland, which was seeking access to the Baltic Sea along the Vistula between Pomerania and Prussia. In the Kraków uprising of Bailiff Albert , the city sought more rights under the leadership of German citizens, in alliance with other cities and parts of the church. Władysław put down this uprising, the subsequent repression permanently broke the political influence of the cities. During a rebellion of the Wielkopolska nobility in 1314 against the rule of the Dukes of Glogau, the Duchy of Wielkopolska became part of the Władysław Empire. In 1320 he was crowned King of Poland. In 1325 Władysław tried to exploit the unclear situation in the Margraviate of Brandenburg, which arose after the Ascanian line of Brandenburg died out in 1320, in an alliance with Lithuania, whose head of state was still "pagan", and limited the territory of the Brandenburg counts to the area west of the Oder . Which a few years later gave the Teutonic Order the pretext to take action against him. He was openly supported by the Lubusz Bishop Stephan II. To the annoyance of his new sovereign, the Margrave Ludwig from the House of Wittelsbacher . The armed conflict brought hardly any land gains for Poland and left an area of scorched earth in the Neumark. In 1329 peace was made with the Brandenburgers because the Luxembourgers allied themselves with the Knights of the Order against him. In the winter of 1327 King John of Bohemia moved against Cracow, but had to back down under Hungarian pressure, but many dukes of Silesia paid homage to him. After 1331, many Piast princes of Silesia recognized the Bohemian feudal sovereignty.

An expansion policy of the Teutonic Order directed against Poland led in 1329 to the loss of the Dobriner Ländchen and Kujawien in 1332; After the Battle of Płowce in 1331, against the combined armies of the Knights of the Order and the Bohemians, the Polish king could not prevent the annexation of both areas. In view of the weakness of the Polish king, the Duke of Mazovia, Wacław von Płock, swore the Bohemian king the oath. The king died during an armistice in the summer of 1332. Power passed to his son Casimir, who was crowned King of Poland immediately after his father's death and who inherited a difficult inheritance. Władysław went down in Polish historiography as a unified Poland. The embrace of the German territorial states, he opposed alliances with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Hungary . In the fight against the German feudal lords and the German patriciate in Polish cities, he found strong support in the Polish Church and the Pope. The kings of Bohemia derived claims to the crown of Poland and the Silesian principalities. Despite these circumstances, he was able to consolidate his work with a coronation as King of Poland. However, Władysław failed to achieve the goal of regaining the old piastic borders. He bequeathed only two old Piast domains to his son, Greater Poland with the center of Poznan and Lesser Poland with Cracow.

King Casimir the Great

Casimir III took over from his father's political legacy . the alliance with the Kingdom of Hungary and the conflicts with:

- the Teutonic Order around the Duchy of Pomerania,

- with the Luxemburgers Johann and Karl IV. for supremacy in Silesia

- as well as with Johann, who as King of Bohemia also laid claim to the Polish royal crown.

The lands that Casimir inherited were relatively small compared to the borders of the state of 1138. The western border of the empire had been pushed back far to the east, almost into the core areas of the ancient Polans. The Duchy of Pomerania became independent under the Greifen dynasty in the 12th century and, after 1227, became directly dependent on the Ascanian Mark Brandenburg. Western areas of the Duchy of Wielkopolska, in the Oder-Warthe region, were conquered or purchased by the margraves from Brandenburg in the second half of the 13th century. Likewise, in the north between 1309 and 1332, the Teutonic Order of Pomerania, Kujawien and the Dobriner Ländchen appropriated. As early as 1327–1331, under the reign of his father, most of the Silesian Piasts submitted to the House of Luxembourg from Bohemia. The kingdom consisting of Greater Poland, Lesser Poland and some Central Polish countries was given the name Corona Regni Poloniae . Due to its military and political inferiority compared to the Bohemian and German sovereigns, Poland continued to find itself in an extremely critical situation. Unlike his father, who wanted to force solutions through military decisions, Kasimir sought more peaceful and diplomatic solutions. King Casimir therefore tried to settle the conflict with John. In the Treaty of Trenčín and the Compromise of Visegrád in 1335, as well as after a Bohemian-Polish border war in 1345 and the death of his ally in the empire against Bohemia, Emperor Ludwig IV , in 1347, Casimir finally recognized the Bohemian suzerainty over Silesia in the Treaty of Namslau . This was a great foreign policy defeat for Casimir. The renewed kingdom was ultimately unable to regain the old Piast territories, which was a major foreign policy goal of the last Piasts. Finally, the Bohemian King Charles IV, since 1346 also the Roman-German (counter) king, incorporated Silesia in 1348 into the lands of the Bohemian Crown. The only connection that existed between the Silesian province and Poland over the centuries was their ecclesiastical affiliation to the Archdiocese of Gniezno, which lasted until the 19th century.

Since the western areas of early and high medieval Poland became part of the Holy Roman Empire at the beginning of the 14th century, also ethnically as part of the German colonization in the east, the Polish rulers oriented themselves eastward. By Abdrängung Poland in the Eastern part of the continent, he submitted in the years 1340 to 1366 that of the Ruthenian inhabited Kingdom of Galicia-Volhynia , also called Red Russia, with Podolien his rule. In 1343, Kasimir made peace with the Teutonic Order, renouncing the use of Pomeranians and the Kulmer Land. For this he got Kujawien and the Dobrin countryside back. King Casimir also sought to consolidate his influence in Pomerania through an alliance with the Griffins, which led to the occupation of some Netze and Neumark districts. In 1348 the plague spread across Europe. Casimir countered this catastrophe by imposing a quarantine on his kingdom so that the epidemic could largely be averted. In the north of his empire, the Duchy of Mazovia was subjugated in 1351. The Piastic-Mazovian duchies, with the main castles Płock and Warsaw, were incorporated into the kingdom after the respective rulers died out. At Kasimir's instigation, an academy was founded in Krakow in 1364, the second in Central Europe after Prague , later called the Jagiellonian University . Casimir promoted the cities through numerous construction measures, including securing the borders of his empire with 50 fortified castles, as well as the admission of Germans and the granting of German city rights. After the pogroms in Western Europe in the wake of the plague, he invited the Jews to Poland, reformed the military system, fought robber barons, had the Polish legal and monetary system standardized, secured new trade routes and favored the opening of salt pans. The economic reforms required the constitutional codification of land law, the statutes of Casimir the Great and the introduction of the General Starosteien with administrative and judicial powers, State Council and chancellery management. He created his own courts of appeal for Magdeburg city law . King Casimir died in 1370 and left no male heir entitled to inherit, which means that the Piast family died out. Although the restored Piast monarchy in the 14th century was able to halt the pushing back of its western borders by the expanded East German territorial states and partially revise them, the Polish territory in the west and in the north at the end of the dynasty in 1370 was compared with the territorial stock around the year 1000 got smaller. In addition to the expansion of Brandenburg and the German monastic state, this had also brought about the German colonization in the east , which led to the separation of Pomerania (1180), Pomerania (1309/1343) and Silesia (until 1335) from the Union of the Monarchy.

As his successor he appointed his nephew, the Hungarian King Ludwig von Anjou, who united Poland with Hungary in a personal union until 1382 . After Kasimir's death, Poland was connected to the Hungarian royal family in 1370. The Hungarian king, Ludwig von Anjou , came from the house of Capet-Anjou . Due to his absence from staff, he was unpopular in Poland. He left the business of Poland to his Polish mother Elisabeth as regent. He also began to claim Galicia, which had become Polish, for Hungary, which met resistance from the Polish aristocracy. Since he had no sons, the Polish nobility were granted political privileges and almost complete tax exemption in the Kaschau privilege in 1374 , which confirmed and enforced the female succession to the throne. The Kaschau privilege became the basis of later aristocratic democracy in Poland. Ludwig died in 1382 and the affairs of government in Poland passed to his daughter Hedwig von Anjou . She was crowned the ruling Polish king in 1384. However, she had to break her engagement to Prince Wilhelm von Habsburg , as the Polish aristocracy, who were mostly anti-German, did not want any German aristocrats as their kings.

1386–1569: Polish-Lithuanian personal union

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was one of the largest states in Europe; it stretched from the Black Sea to the Baltic Sea. Due to its long borders, it had many enemies: the Teutonic Order, the Grand Duchy of Moscow and the Tatars constantly threatened the relatively loose state structure. The Lithuanians therefore promised themselves support against external enemies from the union with Poland.

The previous epoch was replaced by an era in which the history of East Central Europe was mainly characterized by the formation of dynastic great empires and their interpenetration in the classroom. This was made possible by the numerous Interregna after the extinction of the East Central European founding dynasties in Hungary, Bohemia and Poland in the 14th century. Poland immediately used the new trend to regenerate its foreign policy position on the northern flank. Through skillful diplomatic use of its improved position in the old Russian southwest, in Halicz and Volhynia , Poland succeeded in bringing about dynastic union with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which had expanded strongly towards western Russia. The marriage of the Polish ruler Hedwig von Anjou with the Grand Duke of Lithuania resulted in a personal union between the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Together, at the time of the merger, the two countries formed the largest country in Europe. The sphere of influence of the new monarchy, which was called the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania , was expanded to the north, east and south by Władysław II Jagiełło, as Grand Duke Jogaila was called since his coronation. The union was not an incorporation of Lithuania, but rather a dynastic personal union of two different parts of the empire. For the Polish crown, the union brought a considerable increase in power and territorial expansion. At the same time, she was drawn into conflicts with Lithuania's neighbors.

Fight against the Teutonic Order

With the baptism of the Lithuanian Prince Jagiello, the Teutonic Order also lost its last legitimation for missionary conversion in the Baltic States. As a result, Poland had suddenly built up a great potential for power against the Teutonic Order, although there was not yet an exact coordination of Polish and Lithuanian politics. The Teutonic Order was plunged into a serious crisis due to the changed political situation, as its tasks in the Poland region ceased to exist. This turned into the prohibition of Pope and King Wenceslas to continue his campaigns in Lithuania.

In 1410 the German Order was defeated in the Battle of Tannenberg , which caused the Order to lose its aura of invincibility. The surrender of castles without a fight seemed to herald the rise of the order in Poland and Lithuania. The successes were not based on Polish-Lithuanian cooperation against their common enemy - Lithuania almost does not take part in the warfare - the successes were based on the attractiveness of the Polish privilege system for the nobility, which led to a reorientation towards Poland in the neighboring countries. In addition to the Lithuanian-West Russian boyars, an oppositional league was also formed in the Kulmer Land. Knighthood, bishops and cities paid homage to the Polish king and had their rights confirmed. In the First Peace of Thorn in 1411, the Grand Master was able to protect his property against "reparation payments". In the Peace of Lake Melno in 1422, the Dobriner Land and Lower Lithuania fell away from the Teutonic Order .

The Council of Constance withdrew the Teutonic Order's right to proselytize Lithuania , which meant that from a Polish point of view, the order of knights was no longer entitled to exist. The king was politically supported by princes of the Holy Roman Empire in their fight against the order. In 1421, Elector Friedrich I of Brandenburg promised his support against the knights of the order. Polish policy and its goals were becoming more and more evident: territorial revision on the Baltic Sea and expansion of the Polish constitutional model throughout Eastern Central Europe. The Prussian uprising of 1454, the fall of the Prussian estates from their sovereign and the election of King Casimir IV of Poland as the new head, but especially the Thirteen Years War 1454–1466 with the Second Peace of Thorne, 1466 , brought about extensive territorial changes: The German Order was decisively weakened and had to record significant territorial losses. The result was Royal Prussia , which as an autonomous part of the country, like the Duchy of Warmia , was subordinated to the Polish crown. The remaining area of the Teutonic Order became a royal fief. The Polish-Lithuanian Jagiellonian Empire approached its Golden Age after this victory .

The Jagiellonian dynasty rose to become a major European power

King Władysław II. Jagiełło, the founder of the Jagiellonian dynasty, died in 1434. It was only in his fourth marriage that he fathered two male heirs to the throne. The elder Władysław III. A bright future seemed to lie ahead as King of Poland from 1434 until he unexpectedly fell in the battle of Varna in 1440 in the fight against the Ottomans. Due to the four-year absence of a king, the Lithuanian oligarchs had decided to break with the repeatedly renewed union with Poland (1386, 1401, 1413, 1432) by making his younger brother Casimir Grand Duke. The election of Kasimir as King of Poland appeared to be the best solution for the renewal of the Union and the effective defense against Tatar expeditions against both countries. In September 1464, the Union of Brest came into being , a purely personal union , which gave the King-Grand Duke the choice of his place of residence and left territorial points of conflict outside. After three years of Interregnum , Casimir IV received the crown in 1447 . Its focus was initially based on Lithuania, which was able to successfully counteract the waste phenomena of Lithuanian territories on the Lithuanian eastern border. On August 31, 1449 he concluded with Grand Duke Vassilij III. a border treaty that remained in force until the beginning of the Moscow conquests in 1486 and represented the culmination of the Lithuanian acquis in the northeast., As the last living Jagiellon of the Polish line, he saved the biological population of the dynasty and left eleven living descendants when he died in 1490. The large number of children presented the Jagiellonians with the task of acting as a dynasty for the first time. Pure continuity of rule in Poland and Lithuania alone was no longer sufficient to provide for the sons appropriately, since a division of rule was ruled out. So the dynastically oriented policy of the Jagiellonian had to aim at acquiring further kingship and prerogatives for the sons. Appropriate starting points for a dynastic expansion were above all the claims to the crowns in Bohemia and Hungary resulting from the Queen's Luxembourgish-Habsburg origin.

Four of his male descendants were to wear the Polish royal crown after his death. The eldest son, Władysław , had been King of Bohemia since 1471 and received the Hungarian crown in 1490 after the death of Matthias Corvinus . The election and coronation of Władysław as Hungarian king increased the splendor of the dynasty, but also brought it in contrast to the Habsburgs in view of the Habsburg claims on Hungary. The Jagiellonians ruled the vast area between the Baltic Sea, Adriatic Sea and the Black Sea around 1500. The rule in the individual kingdoms took place in different density and quality. The geographical and cultural scope of this rule was limited by the multitude of languages and peoples and religious diversity. With the rule of a dynasty over the entire East Central European area, mutual cultural contacts between the countries belonging to it were also considerably promoted. The size of the Jagiellonian Empire around 1500 was strength and weakness at the same time, because on the one hand it could not be circumvented as a power factor and on the other hand, due to its low internal cohesion, it was hardly capable of unified powerful action. Due to the external threat, the individual rulers of the Jagiellonians came together again for a time to act as a dynastic unit.

The succession of the late Kasimir was divided in 1492 by the brothers Johann Albrecht as King of Poland and Alexander as Grand Duke of Lithuania. The latter followed his brother in Poland in 1501. From 1506 Sigismund took over the rule as Grand Duke of Lithuania and King of Poland as the last surviving son of Kasimir IV.

Loss of territory in the east and south-east

With the expansion of the dynastic empire, this large area of dominion was tied into various areas of conflict on its fringes. In the east, the competition between the extensive Lithuanian empire and the emerging Grand Duchy of Moscow dominated , in the south-east the Ottoman Empire was threatened with expansion, and in the north the Teutonic Order, which was striving for a solution from the Polish hegemony, remained a constant source of unrest. In the west, the Jagiellons were in a dynastic rivalry with the Habsburgs in the struggle for the Hungarian crown and future supremacy in East Central Europe.

- South-East policy: Poland wanted to extend its rule to the Black Sea coast and thus came into conflict with the Ottoman Empire. The defeat of a contingent in Bukovina in October 1497 led to the loss of direct political influence over the Principality of Moldova in 1512 to the Ottoman Sultan. The Sublime Porte set up their vassals, the Crimean Tatars , against Poland and Lithuania. Over the next two centuries, they regularly raided the southern provinces of the empire. In response, the southern border region was populated with free military farmers , which led to the emergence of the later Ukrainian Cossacks . The “ wild field ”, as the areas north of the Crimean peninsula were called , subsequently developed into a “permanent war zone” in the area of tension between its residents.

- Eastern politics: The rise of the Grand Duchy of Moscow became a threat to the existence of Lithuania. It tied all the forces of Poland and Lithuania in the east for centuries. From 1492 (wars of the years 1492–1494, 1500–1503, 1507–1508, 1512–1522) both states were in fact in a permanent state of war with Russia. The armed forces were only interrupted by armistice agreements. In eventful battles on the threshold of the 15th / 16th centuries In the mid-19th century, Lithuania lost large areas of its territory by 1522. In Eastern Europe, the Grand Duchy of Moscow gained power over Lithuania.

- Western politics: The claims to the Bohemian and Hungarian crowns led Poland into competition with the House of Habsburg . In 1515 the agreement was reached in Vienna . Maximilian I von Habsburg and Sigismund I agreed on a double wedding, and the future Hungarian king married the Habsburg Maria. In return, Habsburg renounced the support of the Grand Duchy of Moscow and the Teutonic Order. When Ludwig II fell in the battle of Mohács against the Ottoman Empire in 1526 , Poland's influence on Hungary also ended. Instead, the Baltic Sea region took first place in the power struggle for foreign policy.

Despite the essentially offensive policy, Poland soon began to withdraw on itself. Neither the royal family nor the nobility, which was gaining more and more power, were able or willing to be the leading power in the East as they were in the 15th century. The incipient decline in power in Poland was masked by a subsequent period of inner calm, because the potential winners of the sudden Polish abstinence, Sweden and Russia, were in turn too weak to fill the vacuum created by Poland. This and the ties between the Spanish-Austrian and Ottoman forces in its south gave Poland a deceptive calm for about 100 years. The Jagiellons had to grant privileges to the nobility. The Polish Diet, which was made up of the nobility and clergy, gained increasing power over the king. In 1505, the Nihil Novi constitution laid down extensive participation rights for the Sejm. The privilege of the nobility and their increase in power led to the disenfranchisement of the peasant and middle class. With a view to strengthening his power, Sigismund enacted a series of reforms, established a conscript army in 1527, and expanded the bureaucratic apparatus necessary to rule the state and finance the army. With the help of his Italian wife, Queen Bona Sforza, he began buying land to expand the royal estate. He also began a process of restitution (restoration) of royal goods that had previously been pledged or given as fiefs to members of the nobility. In 1537 the king's policy led to a major conflict, known as the Chicken War . The Szlachta, the lower nobility, gathered near Lemberg for a levée en masse and demanded military intervention against Moldova. The small and middle nobility began a rebellion with the intention of inducing the king to abandon his reforms.

Albrecht von Hohenzollern, Grand Master of the Teutonic Order, submitted to the Polish King in 1525 and took the new Duchy of Prussia as a fief. The country was secularized and the new evangelical faith guaranteed. As early as the 15th century, a change in economic conditions began to emerge. In the countryside, serfdom and corporal economy prevailed, while the cities, especially Krakow, Danzig, Thorn, Lublin, and later Warsaw, grew into flourishing trading cities of international standing.

1569–1795: Republic of Poland-Lithuania (Rzeczpospolita)

The Treaty of Vilnius presented in 1561 the sphere of in Kurland , Livonia and Estonia footed branch of the Teutonic Order under Polish supremacy. The king guaranteed Landmeister Gotthard Kettler the German language, German law, German self-government and freedom of belief, which later survived under Swedish and Russian rule until the 19th century. The Livonian Confederation thus protected itself against the Russian policy of conquest.

The Baltic crisis, which followed the dissolution of the order in the Baltic States, opened an era of the Northern Wars in which Poland-Lithuania, after the end of the Jagiellonian dynasty in 1572, gradually lost its dominant position in Eastern Europe. The impetus for this renewed turn of the epoch came from Tsarist Russia. When Tsar Ivan IV invaded the politically torn Livonia in 1558 , it unleashed a 25-year conflict on the Baltic coast. This advance called counter-strategies in Sweden, Denmark and Poland, each of which aimed at supremacy in the Baltic Sea. In the First Northern War , Sweden and Poland were initially able to push back Russian power until 1582 and keep it away from the Baltic Sea for a century and a half.

Lublin Union

Under the impression of the Russian offensive in the Livonian War against the Baltic States , the personal union between Poland and Lithuania was converted into a real union with the Union of Lublin in 1569 due to the lack of successors . A majority of Lithuania agreed to the union with Poland - against the guarantee of autonomy in the areas of military sovereignty, state finances, jurisdiction and the official language. Poland and Lithuania became the Rzeczpospolita, a republic based on a federation under the presidency of a King of Poland elected for life and Grand Duke of Lithuania in Realunion (officially the Republic of the Polish Crown [Kingdom of Poland] and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ). For Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine, this meant the extensive Polonization of their ruling classes in the long term . At the end of the 16th century, the Rzeczpospolita comprised the area of central, northern and eastern Poland, Kaliningrad Oblast, Lithuania, Latvia, Belarus, Ukraine, Slovakia, Estonia and Moldova.

When electing a king, all noble imperial citizens should assemble on the electoral field in Wola near Warsaw to determine the ruler in free choice. Every nobleman had a vote, the impoverished country nobleman as well as the most powerful magnate. Buying votes was common. The elected king was forced to make concessions to the nobility with the pacta conventa . He also had to conjure up the Articuli Henriciani . The king was regarded as primus inter pares , real power lay in the hands of the high nobility, who exercised it through sole possession of all state offices and rulership over the subjects. Since the constitution, the Nihil Novi of 1505, the head of state has not been able to pass a new law with his two chambers without the consent of the Reichstag.

The principle of unanimity for all Reichstag resolutions had been in effect since the 16th century, but was only applied since 1652 in such a way that a single MP with the call of the Liberum Veto could block parliament and invalidate all resolutions passed so far. The problem of these regulations was recognized by many, but power and social disinterest of the large landowners prevented reforms. Most of the cities remained without political influence and, like the defense of the country, were neglected because the nobility refused to raise the necessary financial resources to set up a powerful army. As a result of the refusal to pay taxes, the state treasury remained notoriously damp from the establishment of the common state until its demise. As a result, the Polish-Lithuanian republic had to be defended with small armies on several fronts. The situation of the oppressed peasant class was bad because of the forced labor and personal lack of freedom. Characteristic of the political development of this time is the formation of a " noble nation " with Polonized Lithuanian, Ruthenian and German-Prussian-Baltic nobility, while the rural population in the north and east of the country remained predominantly German, Lithuanian, Belarusian and Ukrainian-speaking. After 1572, the Polish Imperial Diet of Magnates increasingly restricted the power of kingship and permanently secured the privilege of electing a king.

Reformation and Counter-Reformation

The Reformation spread rapidly in Poland and Lithuania. The Calvinism was in 1540 by Jan Łaski taken to Poland. Under the influence of the Unitarian , Faustus Sozzini , the Church of the Socinians was founded in 1579 . The Lutheranism had found initially in the German population in the Prussian cities and in Krakow collection, in the Duchy of Prussia, the lessons began Luther and Calvin enforce. King Sigismund I fought them politically with a series of edicts and rights restrictions, in Danzig also militarily. His son and successor Sigismund August, in whom the Protestants had high hopes, did not change denominations, but did not take any vigorous action against the Reformation. In the years after 1548, Reformation communities of various stripes formed in a number of places: in the west of the country the expelled Bohemian brothers in Leszno and Ostroróg , in the east Arians and Anabaptists in Raków and other media cities of noble magnate families. The Protestant schools of the Rzeczpospolita concluded the Sandomir Consensus in 1570 . With the "Pax Dissidentium" of the Confederation of Warsaw in 1573, the unrestricted freedom of religion of Protestants, including their political equality and civil rights, was sanctioned under constitutional law.

The fragmentation of the movement in different directions was a weakness on which the Counter-Reformation began, which began in Poland with Stanislaus Hosius , the Bishop of Warmia. The foreign policy leaning of the following three Wasa kings to the Catholic Habsburg and the domestic political struggle against the nobility pushed the Protestants back further and further. However, there was no institution like the Inquisition in Poland and no one was burned at the stake. The Polish tolerance of that time was explained by the fact that the representatives of the dominant nobility wanted to save themselves a religious war like in the neighboring Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation or Huguenot France. A balance was found with a part of the Ruthenian Orthodox Church in the Church Union of Brest , which was concluded in 1596 . This was intended to secure the eastern border, but did not meet the expectations of the state leadership and the local dignitaries involved. From the middle of the 17th century, the country began to become more and more re-Catholic , and religious and national minorities were increasingly marginalized. It encouraged the emigration of large parts of the Protestant population, which meant that the country's economic and intellectual potential was permanently lost.

Golden century

Art, literature and science reached a climax in the "golden century" of the Renaissance and humanism , especially during the reign of the Renaissance king Sigismund the Elder, an upswing in literature and art, with Latin, which had dominated the literature up to that point, being replaced by Polish fully unfolded from around 1500. The “Vistula Gothic” flourished, the Italian Renaissance penetrated the “Krakow School of Painting” and the influence of German and Flemish artists, including Veit Stoss, increased . At the Kraków Academy , a center of humanism, Conrad Celtis and the lawyers Paweł Włodkowic and Jan Ostroróg worked . Through the immigration of German printers, wood carvers and publishers, Krakow rose to become the leading center of book printing in East Central Europe. The poets Mikołaj Rej , Jan Kochanowski and Łukasz Górnicki founded Polish literature , the philosopher Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski the Polish state theory and Nicolaus Copernicus the heliocentric worldview . Italian and French influences were reflected in architecture and art. Numerous aristocratic palaces, town houses and churches were built, the royal castle on Wawel Hill was expanded into a magnificent residence, and new cities were founded. The Chancellor Jan Zamoyski had a Renaissance model city, Zamość , built, the cities of Lemberg , Vilnius and Posen became important cultural centers, the Prussian Hanseatic cities of Elbing , especially Danzig , became the country's most important trading ports.

Struggle for control of the Baltic Sea

Second sovereign of the "Rzeczpospolita" in 1573 was the French Prince Heinrich von Valois . However, the king suddenly left his throne after a few months of reign without having formally abdicated. He had from the death of his brother Charles IX. , King of France and was able to secure the French crown, which was connected with more power, by being present at the Paris court. Heinrich left behind the Pacta conventa and the Articuli Henriciani, which had a constitutional character and reduced royal rights to a minimum. The rights and privileges granted by him, despite his short "rule of 146 days", became the basis of the golden freedom and established the prominent position of the aristocratic republican aristocracy . Heinrich let the return date set for him pass by. He was declared forfeit of the crown and with Stephan Báthory , who had strong support from Jan Zamoyski , a Hungarian aristocrat from the Principality of Transylvania was able to successfully assert himself in Poland in 1576 . Báthory was a skilful tactician in the power structure of the republic and led his army victoriously against the Moscow state in the Livonian War. In three campaigns ( Polotsk 1579, Velikije Luki 1580 and Pleskau 1581) he defeated the Tsar, who finally concluded an armistice with the Polish king in the Treaty of Jam Zapolski . The Tsar ceded the area around the city of Polotsk, which had been conquered in 1563, and Livonia with Dorpat, which had been partially annexed since 1558, to the Polish crown. Stephan Báthory founded the University of Vilnius in 1579 with the help of the Jesuits whom he brought to Poland and promoted . The plan to liberate his Hungarian homeland from Turkish rule with the help of Poland could not be realized because of his sudden death in 1586.

1587 was Sigismund III. Wasa , who united the race of the Jagiellonians and the Wasa in his person, was elected king. The election of a Swedish prince favored the outbreak of momentous Swedish-Polish wars . In 1592 Sigismund III. additionally Swedish king and thus established a Swedish-Polish personal union. However, when he was elected, the Sejm had obliged him to be permanently present in Poland. So Sigismund III. appoint a regent in Sweden. 1603 tried Sigismund III. Wasa regaining the throne of his Swedish homeland, which he had lost as a result of the Battle of Stångebro in 1598 and his deposition as King of Sweden by the Swedish Diet in 1599. This resulted in the end of the personal union between Sweden and Poland, which existed from 1592 onwards, and provoked the outbreak of the Swedish-Polish wars 1600–1629 . For Poland this brought the loss of Livonia and Prussian coastal areas. King Sigismund moved the capital of Poland from Krakow to Warsaw in 1596 because of its central location in Poland and the greater proximity to his hereditary kingdom of Sweden. At the same time as the war against Sweden, there were conflicts with the Ottoman Empire and with Tsarist Russia.

- The king intervened in the Russian throne chaos, the Smuta , which broke out in Russia after the death of Tsar Boris Godunov around 1605. During the conflict that lasted from 1609 to 1618 , in 1610 Polish-Lithuanian Union troops under the leadership of the crown field hetman Stanisław Żółkiewski occupied Moscow for two years. A desired personal union failed because of Russian resistance to the royal plans and the internal constitution of Poland. After eventful battles, the war came to an end with the Treaty of Deulino in 1618. King Sigismund received rule over Smolensk and Severia. With this, the aristocratic republic reached its greatest territorial extent with a state area of almost 1,000,000 square kilometers. After Sigismund's death and breaking the treaty concluded in 1618, Tsar Michael tried to enforce his territorial claims to the lost territory in the " Smolensk War " from 1632, which resulted in defeat due to the timely relief from the new Polish king, Władysław IV. Wasa of the Russian state flowed.

- The foreign policy of the Polish Wasa, oriented towards the Habsburgs, and the raids by the Cossacks on Turkish territory, shattered the relatively good relationship with the Ottoman Empire, also due to the many raids by the Tatar peoples, Ottoman vassals, against the provinces of the kingdom. After Cossack-Tatar border skirmishes, interference of local magnates from Ukraine in the internal affairs of the Ottoman vassals, the Danube principalities , the Ottoman-Polish War 1620–1621 broke out . Sultan, Osman II , assembled a force of up to 300,000 men against the republic, which the Polish king opposed at Chocim with a mixed Polish-Ukrainian army (up to 75,000 troops , including 6,450 Germans). When the Ottomans, despite their numerical superiority, failed to break through the Polish-Ukrainian front after more than a month, both sides agreed to an "honorable" armistice.

Age of the "Bloody Deluge"

In 1648 John II Casimir became the new Polish king. Hardly in power, tensions intensified in the southeast. The feudal and religious pressure on the Ruthenian population sparked another major uprising, the Khmelnytskyi uprising led by Bohdan Khmelnytskyi against Polish rule. The Cossacks plundered the properties of Polish landowners, brought large parts of Ukraine under their control and advanced with their army as far as Lviv. At the same time Chmielnyzkyj was against living in Ukraine Jewish pogroms perpetrate because many of them served as Polish managers. According to recent estimates, the pogroms killed almost half of the approximately 40,000 Jewish residents of Ukraine, and many of the survivors fled the country.

After eventful war events, the conflict came to an end in 1654. The Cossacks switched to the sovereignty of the Russian Tsar. The change of side was not without controversy within the Cossack nation, since some preferred to reunite with Poland. The deep divisions left the Ukraine area in war-like conditions and chaos for decades. The annexation of eastern Ukraine to Russia led to the Russo-Polish War from 1654 to 1667 . In the spring of 1655 this led to the occupation of a large part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Ukraine by Russian troops. When Johann Kasimir declared himself king of Sweden in 1655, he gave the Swedish king Karl X Gustav the welcome occasion to attack Poland. The Thirty Years' War had emptied the Swedish treasury, and at the same time an expensive army had to be maintained in the conquered countries. Sweden's advance was favored by the different interests of the Polish magnate houses and the military situation of the republic in the east. The Wielkopolska aristocracy surrendered to the Swedish armed forces without a fight and then paid homage to Karl X. Gustav as their king. One after the other, the most important cities fell into Swedish hands: Warsaw in September and Krakow in October. The Russians, in alliance with the Cossacks, advanced as far as Lublin , Puławy and the Vistula .

King John Casimir was abandoned by most of the nobility and fled to the Holy Roman Empire in Silesia, where he hoped for help from the Habsburgs. In Lithuania, in view of the Russian successes, the nobles agreed to a union of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania with Sweden , which meant the break of the real union with Poland. However, the number of Swedish troops was insufficient to hold the conquered territories. The representatives of the Polish nobility also changed fronts and organized themselves into the Tyszowce Confederation . Moreover, the Russian Tsar Alexei fell out with the Karl Gustav on the division of conquests and explained to him the end of May 1656 the war , while the Polish king a limited two-year ceasefire Niemież concluded. The Swedish-Polish and Russian-Polish Wars thus expanded into a Swedish-Russian-Polish conflict, the Second Northern War . Johann Kasimir returned to Poland in early 1656. In 1656 the Elector Friedrich Wilhelm von Brandenburg , who was subject to Karl Gustav, accepted his offer to make him sovereign Duke in Prussia for an alliance. With the victory of the Swedish-Brandenburg armed forces over the aristocratic republic's troops in the three-day battle near Warsaw , Karl Gustav recognized the sovereignty of the Duchy of Prussia in the Treaty of Labiau in 1656.

Karl Gustav saw his only hope in a victory over Poland and the partition of the republic with the involvement of Transylvania, Brandenburg and Chmielnicki. At the beginning of 1657, the principality of Transylvania, which was under Ottoman protection, took the side of the Swedes under the leadership of the Protestant Georg II Rákóczi and devastated large areas of Poland in the south and east with his Transylvanian-Cossack army. To prevent Sweden from becoming overweight in Northern Europe, the Kingdom of Denmark and the Habsburg Monarchy under Emperor Ferdinand III allied . and the Netherlands with Poland. The Swedish defeats from mid-1657 onwards, Friedrich Wilhelm, who had remained waiting, took the opportunity to ask Archduke Leopold to mediate with the Polish king. Poland's top government accepted the offer to change sides in Brandenburg. Poland now also granted the Duchy of Prussia full sovereignty. This should enable the son of Friedrich Wilhelm to elevate the duchy to the Kingdom of Prussia in 1701 .

Territorial losses and Poland as a pawn for European powers

The war with Sweden lasted until the Treaty of Oliva in 1660. The treaty established the status quo ante bellum . The Elector of Brandenburg gained sovereignty over the Duchy of Prussia. France assumed the guarantee of keeping the peace. The tsar's troops could now be pushed back as far as the Dnieper. The victories of the renegade magnate Jerzy Sebastian Lubomirski and the change of power in the Crimean khanate, which threatened the southern border, resulted in the conclusion of an unfavorable armistice with Moscow in 1667. With this, Poland lost over a quarter (a total of 261,500 km²) of its territory, which from 1667 amounted to 733,500 km². In 1668 the last Vasa king, Johann Casimir, abdicated. A quarter of the population at that time had died as a result of epidemics, famine, looting and acts of violence. Additional population losses resulted from the loss of territory to Russia and the Polish economy was also shattered. Manfred Alexander describes Poland's situation after the resignation of Johann Kasimir as follows: “In five years, Poland lost as many people in percentage terms as Germany did in the Thirty Years War , the main burden was borne by the cities. Their planned and methodical destruction [... led to] Poland remaining an agricultural country. It was not until 1848 that the cities returned to roughly the level of 1655. ”In 1669 the Sejm elected Michael Wiśniowiecki as King of Poland. Four other candidates were rejected because the representatives of the small nobility wanted to give their vote to a local candidate after bad experiences with foreigners, in contrast to the noble Republican magnates.

The state of war existing in right-bank Ukraine culminated in the Ottoman-Polish War from 1672 to 1676. In order to forestall an imminent military defeat, the weakened Poland concluded the Preliminary Peace of Buczacz . Ottoman Turkey extended its rule over large parts of southern Ukraine. The Polish Reichstag refused to ratify the treaty; acts of war began again. After eventful battles, the war ended in 1676 with the Treaty of Żurawno . King Wiśniowiecki died in 1673. The Grand Crown Hetman Jan Sobieski was elected as his successor in 1674 thanks to his popularity and military merits.