History of the Ruhr area

The history of the Ruhr area describes the development of a region that was already an important traffic junction in the Middle Ages and gained great importance in the age of industrialization due to its coal deposits .

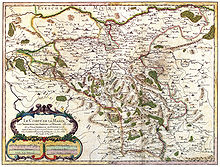

In the Middle Ages, counties developed in the region , the most important of which were those of the Counts of Berg , the Counts of Mark and the Counts of Cleves . With the Hellweg there was a continuous economic traffic axis in the region. Important cities in the region developed along the road. Since the end of the 14th century, the Counts of the Mark were counts, later dukes of Cleves. From 1521 onwards, all of the count's territories in the area of the United Duchies were brought together under one rule.

As early as 1609, Kleve and Mark fell to the Electorate of Brandenburg , which marked the beginning of a development towards Prussian rule in the region. By the beginning of the 19th century Prussia also took control of some smaller territories in the Ruhr region, such as the spiritual territories of Werden and Essen. Finally, the area of the county of Dortmund was also brought under Prussian rule. This meant that the large number of territories inherited from the Middle Ages had finally fallen to one ruler, and the development of the industrial region in a uniform legal system had become possible. Only the Prussian provincial borders ran within the Ruhr area. As administrative district boundaries, they have been preserved to the present day. In 1946, the state of North Rhine-Westphalia was formed around the Ruhr area.

The Ruhr area was considered crucial for the control of the German economy during the reconstruction period and should be protected from French or Soviet access. The planned creation of a regional council for the Ruhr area will take into account the uniform economic development of the region in a reformed administrative system in the state.

Prehistory and early history

Devon

465 million years ago the Ruhr area lay on the small continent Avalonia , to which the cores of northern Germany, Belgium, central England, central Ireland Newfoundland and Nova Scotia belonged. In the Lower Devonian, the small continent collided with Laurussia .

Carbon

In carbon , a geological section of the Paleozoic Era , which began 360 million years ago and ended 300 million years ago, formed layers with shale , coal and sandstone . 400 to 300 million years ago, new mountains formed in the Variscan Orogeny .

The layers that became coal seams over millions of years were deposited in the Westfalium . During this period of the earth's history, the swampy landscape and the floods of the sea alternated, so that the deposits of plant materials and sediments of the sea are passed down today as a series of layers of coal and rocks lying in between.

The dominant representatives of the flora in the coal swamps were the genera Lepidodendrales and Sigillaria , tree-like plants that belong to the plant division of the bear moss plants (Lycopodiophyta). The representatives of both genera reached sizes of up to 40 meters with a trunk diameter of over one meter.

Cretaceous period

In the Cretaceous Period 135 million years ago to about 65 million years ago, a tropical ocean covered the country. Ammonites lived in its water . A thick layer of marl formed at the bottom of the sea . The sediments were deposited over the layers of carbon and also preserved the shells of giant ammonites.

Ice age

The ice age brought a change between warm and cold periods. During the Drenthe stages of the Saale Ice Age , the glaciation of northern Germany reached as far as the Ruhr , which lies in front of the northern edge of the low mountain range . The morphology of the middle and lower Ruhr valley was shaped by the flowing melt water and the force of the ice. The meltwater flowed west through the Ruhr valley. Where Essen is located today , the outflow was temporarily blocked by a barrier made of ice masses and rubble, so that a huge ice age lake was dammed up that filled the valley near Schwerte .

First settlements

80,000 BC BC - The region of today's Ruhr area was settled in the Middle Paleolithic at the time of the Neanderthals around 80,000 years ago. During the construction of the Rhine-Herne Canal in Herne in 1911, stone tools and storage marks with bones of woolly rhinoceros , bison and mammoth were found. People camped in other places in the Emschertal as well . Further finds from the 1960s prove this for the Boyetal (pronounced Beu) between Bottrop and Gladbeck .

8700 BC Chr. - The finds made in November 1978 of Stone Age flint tools from Duisburg Kaiserberg belong in the late phase of the last ice age and can v to about 9,000 to 8,000 years. To be dated. The oldest remains of anatomically modern people in the area of today's metropolitan area come from the early Mesolithic . They were discovered in the spring of 2004 in the leaf cave near Hagen-Hohenlimburg .

Middle and New Stone Age 6000–4500 BC Chr. - From the La Hoguette group finds of pottery are known which cause the lip seen as the northern distribution line. Several settlements in the vicinity of Bochum , Hagen and Dortmund are known from the band ceramics and the Rössen culture . In spring 2004 the skeletons of several people of the Michelsberg culture were discovered in the leaf cave near Hagen-Hohenlimburg . Among them was the skeleton of a 17 to 22 year old woman. These finds are the only closed evidence of burials from this period in the conurbation on the Rhine and Ruhr.

antiquity

The history of the Ruhr area in the ancient era can be roughly divided into two phases:

Conquest of the Germanic peoples

Finds on a burial ground in Oespel near the Oespeler Bach indicate a settlement in the early Bronze Age . Large amounts of charred grain and acorns were found in cylinder pits on the edge of the burial ground, which were dated back to the 17th to 18th centuries BC using the radiocarbon method . With the few circular ditches in relation to the number of graves, the grave field of Gladbeck sets itself apart from the well-known Young Bronze Age (1700 to 1200 BC) grave fields in northern and north-eastern Westphalia, where it was customary to keep the majority of burials.

From around 1100 BC Population groups belonging to the Urnfield Culture immigrated to the Ruhr area, which became a peripheral area of the cultural area. This immigration was associated with a considerable increase in the population, which is proven by numerous grave finds. In the Duisburg area, cemeteries of the Urnfield people were found in Wedau , Beeck , Obermeiderich , Hamborn , Marxloh , Bruckhausen , Wittfeld and Neumühl .

The Proto-Celtic population that immigrated from the south came from around 800 BC. Chr. Increasingly under the pressure of populations immigrating from the north-west into the Ruhr area, who can be identified as Proto-Germanic due to the pottery . Between 600 and 400 BC The process of conquering the Germanic peoples in the Ruhr area should have been completed.

The Germanic groups crossed to the left bank of the Rhine and displaced the Celtic population from what is now the Netherlands and parts of what is now Belgium . This process is largely in the dark historically, there are no written sources, only archaeological evidence provides information about it.

Confrontation between the Germans and the Romans

Until 13 BC Chr.

During the conquest of Gaul by Gaius Iulius Caesar , we received for the first time more detailed information about the Germanic tribes who settled in the Ruhr area. The Sugambres settled east of the Rhine, south of the Lippe as far as the Bergisches Land, the Usipeters to the north of the Lippe on the Rhine , the Brukterer to the east, the Martians villages to the east of Dortmund and the Ubier and Tenkerians to the south in the Cologne area .

For the first time the Germanic tribes settling in the Ruhr area came with the Romans in the year 55 BC. When the Tenkerer and Usipeter invaded Gaul, were defeated there by Caesar and after the defeat fled to the Sugambrians and asked for asylum there. The Sugambres opposed Caesar's demand to hand over the asylum seekers.

From around the year 50 BC. The area on the left bank of the Rhine was under Roman control and belonged to the Roman province of "Gallia comata". In the year 16. BC The tribes of the Sugambrer, Usipeter and Tenkerer invaded the Roman province. The army of the Roman provincial governor Marcus Lollius Paulinus was defeated by the Germanic peoples, who managed to capture the legionary eagle of the 5th Legion. The defeat went down in Roman history as the “ Clades Lolliana ”. Under the impression of defeat, Augustus went to Gaul and stayed there until 13 BC. The defeat of Lollius is often used in literature as a trigger for the beginning of 12 BC. Roman attempt to conquer Germania.

Roman attempt to conquer Germania 12 BC Chr. To 16 AD

Between 12. BC and AD 16, the Romans tried by numerous campaigns in the interior of Germania to subdue the free Germanic tribes and to move the imperial border from the Rhine to the Elbe .

At the same time, the Rhine border was secured by the establishment of Roman military camps. The most important Roman military camp Vetera near Xanten was built in 13 and 12 BC. Built in BC. In the year 12 BC The construction of the Roman Asciburgium fort on the border between today's Moers and Duisburg and the Werthhausen fort in today's Duisburg-Rheinhausen also fell . From this time on, the Romans began to expand the Lower Germanic Limes .

The 12 BC First to 8 BC. Campaigns carried out by Roman armies under Drusus were directed - probably under the impression of the Roman defeat in 16 BC. BC - against the Usipeter and Sugambrer .

During the second campaign in 11 BC BC, the Roman troops under Drusus pushed along the Lippe eastward and reached the Weser . To control the Sugambrians who were settling in the Ruhr area, Drusus had an army camp set up near Oberaden .

A large part of the Sugrambrer was born in 8 BC. Relocated to the left Lower Rhine to bring the tribe under the control of the Roman legionary camp Vetera. The army camp in Oberaden was then abandoned. The Sugambrers who remained on the right bank of the Rhine were absorbed by the neighboring tribes, the Sugambrers who had moved to the left bank of the Rhine were later referred to as Cugernians .

At the turn of the times, Roman military bases were set up along the Lippe. Well known are the Roman camp Holsterhausen, the Roman camp Haltern , both in the Recklinghausen district and the most easterly discovered camp in Anreppen in the Paderborn district . The best-researched fort is Haltern am See, where there is now a Roman museum .

Even after the Varus Battle in autumn 9 AD, the Romans invaded the Germania on the right bank of the Rhine in several campaigns. The campaign affecting the Ruhr area took place in the spring of 14, when an army under Germanicus moved up the lip to the east of Lünen and marched back to the Rhine via the Hellweg . From 17 onwards no more important campaigns took place here and the Romans withdrew to the left bank of the Rhine.

Romanization and border security

In the first century AD, after the expansionist efforts were abandoned with the establishment of the Lower Germanic Limes, the border security phase began. The process of Romanization , which had begun under Augustus , gained increasing momentum in the first two centuries, as numerous former soldiers, who came from all parts of the Roman Empire, settled in the border belt on the Rhine and thus helped shape the population of Lower Germany. In addition, there were the soldiers of the Germanic auxiliary troops who, after 25 years of service, started their own business as merchants or farmed with their release money. But the economic life of the local Germanic population also flourished, as the troops stationed on the Rhine had to be supplied and equipped.

Against the background of the civil war fought in the Roman Empire and the withdrawal of Roman troops from the Rhine border, the Batavians were supposed to provide further troop contingents, which in the summer of 69 AD led to the Batavian revolt under Iulius Civilis . Asciburgium and Vetera were destroyed. At Vetera there was a battle in the year 70, in which the Roman troops were victorious. The legion camps were rebuilt.

In 85 the garrison was relocated from Asciburgium to Duisburg - Werthausen , where the small fort in Werthausen was built to secure the crossing of the Rhine and the mouth of the Ruhr .

Around 90 there was a reorganization of the Roman administration by separating the Upper and Lower Germanic military district from the province of Belgium and forming the provinces of Upper and Lower Germany. The area on the left bank of the Rhine north of Andernach belonged to the province of Germania inferior from then on .

In connection with the urbanization of their Lower Germanic province promoted by the Romans, the Colonia Ulpia Traiana , near today's Xanten, received Roman town charter in 110 .

Crisis and collapse of Roman rule on the Rhine

At the beginning of the 3rd century several Germanic tribes on the right bank of the Rhine joined together to form the Franconian tribal association , which is divided into two groups: the Upper Franconians and the Lower Franconians, who had their domicile on the right Lower Rhine and into which the tribes of the Sugambrer, Salian Franks , Chamavers and Chattuarians opened. The tribal name was common among the Romans from the middle of the 3rd century.

After there had been raids by smaller Germanic groups into Roman territory since the beginning of the 3rd century, a larger group of Frankish warriors broke through the Lower Germanic Limes in the winter of 256/257 and penetrated deep into the Roman province of Gaul. Since the Roman troops were concentrated on the Limes, the Franks encountered little resistance in the interior of the Roman province. Part of this Frankish warband even advanced into Spain and conquered Tarraco, today's Tarragona , on the Spanish east coast. In the following years there were frequent raids by Franconian warbands into Roman territory.

The Colonia Ulpia Traiana was badly damaged by a Frankish attack in 275 . The huge Tricensimae fortress was built in its place at the beginning of the 4th century .

The most serious attack by Germanic groups to date into Roman territory took place in the spring of 276, when not only the Alamanni in southern Germany invaded the Roman province, but at the same time Franconian war bands broke through the Lower Germanic Limes. For the first time, Elbe Germanic tribes such as the Vandals , Lugians and Burgundians were involved in the invasion. The Teutons sacked the Roman province of Gaul for about a year before the Roman Emperor Probus was able to fight them effectively. The fighting against the Germanic looters in Gaul lasted until 281.

After the Roman Emperor Maximian won a victory against the Lower Franconians in 291 after heavy fighting, he settled parts of the tribe on the left bank of the Rhine, i.e. Roman territory.

For the 4th century, wars between Roman emperors against the Lower Franconia have been handed down, for example the campaign of Emperor Constans in 341 and 342. In 355 the Franks conquered the Roman fortress Tricensimae near today's Xanten and destroyed the cities on the left bank of the Rhine and settlements. In 356 Iulian succeeded in regaining Cologne, which had been conquered by Franks. In the following year there was fighting in the area of Jülich, in 358 he won a victory over the Salian Franks, had the Tricensimae fortress rebuilt and in 360 led a campaign against the Franks on the right bank of the Rhine. In the winter of 391 to 392 a Roman army crossed the Rhine to fight the Brukterer . However, the Romans did not succeed in defending themselves permanently against the recurring raids by the Franks, which also lasted in the 5th century.

These numerous Frankish attacks on Roman territory and the withdrawal of Roman troops in 405 led to the loss of the Roman border province of Germania Inferior, which was settled by Franks, at the beginning of the 5th century. When at the turn of the year 406 on 407 the Vandals , Quads and Alans crossed the Rhine and invaded Gaul, Roman rule on the Rhine collapsed and the Romans had to give up the Rhine as a border. In the course of the first half of the 5th century, the Franks expanded westward, although Aetius' victory over the Franks has been handed down again for the year 428 , and around 450 ruled an area that is roughly today's Belgium, the Moselle region and included the Middle and Lower Rhine.

Early middle ages

At the beginning of the 5th century, the western Ruhr area was already relatively densely populated. Ten Franconian burial grounds have so far been identified in Duisburg. In Dortmund, too, a warrior grave from the 6th century was found in a burial ground on the Asselner Feld.

Around 428 Chlodio took over the rule of the Salfranken ; he is their first historically tangible king. According to the tradition of Gregory of Tours , he is said to have resided in a place called "Dispargum", which in older literature was often equated with Duisburg.

The beginning of the fighting between Franconia and Saxony can be dated to the year 556.

At the end of the 7th century Christian missionaries from the Franconian Empire were active in the area of the Franconian Brukterer . With the advance of Saxon settlers, however, the conversion was stopped. The failed mission is reflected in the saintly legend of the black and white Ewald , whose missionary work at Aplerbeck 695 is said to have come to a violent end.

The royal court in Duisburg was probably created in 740. 775 the army conquered Franks under the leadership of Charlemagne the Sigiburg , a year later the Eresburg at Niedermarsberg . Imperial courts were laid out.

In 796, the missionary Liudger from Friesland began building a church on a property in Essen-Werden . H. Flood-free terrace piece on the Ruhr. A Benedictine monastery, the Werden monastery, was later attached to this church, and the city of Werden developed in the vicinity.

The Normans wintered in 863 on the Bislicher Island near Xanten and destroyed the local church. A few years later, in 880, the Normans set fire to Birten .

The collegiate church in Essen was consecrated in 870 in the women 's monastery founded by the Saxon nobleman Altfrid .

Regino von Prüm reported from the year 883 that Normans wintered in Duisburg, the oppidum diusburh , after they had conquered it. Probably in response to the repeated Viking raids was the castle Broich in an der Ruhr Muelheim built. It also secured the ford of the Hellweg through the Ruhr .

High Middle Ages

Royal stays in the Ruhr area

In the Middle Ages, the East Franconian or German Empire was an “empire without a capital”; H. the kings traveled with retinues in their kingdom. The Hellweg was an important road connecting the Ottonian travel kingdom . Dortmund and other old cities in the Ruhr area, such as Duisburg and Essen, lie along this travel and trade route . The royal court in Duisburg was also expanded into a royal palace.

King Heinrich I spent Easter in Dortmund in 928. The first Christian imperial synod took place in Duisburg the following year. 18 royal stays in Duisburg are documented between 922 and 1016.

In May 938, the German King Otto I held a court day in Steele . Three years later, in 941, Otto I (the great) stayed in Dortmund for the first time . A few years later he also celebrated Easter in the Palatinate . The frequent use as a festival hall underlines its importance.

The decision to campaign in France was made at the Imperial Assembly of Otto II in Dortmund in 978.

On May 7, 992, the young Otto III. Envoy from the King of West Franconia in Duisburg .

An imperial assembly of Otto III. took place in Dortmund in 993. Among other things, a dispute between Bishop Dodo von Münster and the Mettelen Monastery was decided in favor of the monastery.

Heinrich II received his homage in Duisburg in 1002 from the Lorraine bishops and the archbishop of Liège . The Synod of King Henry II in Dortmund followed in 1005 .

In 1011 King Heinrich II handed over the Duisburg royal court to his relative, the Lorraine Count Palatine Ezzo . In the 11th and 12th centuries, the Ezzone created an area of power between the Maas and the Ruhrgau that was no longer subject to ducal power. When the sphere of influence of the Ezzone shifted more to the Middle Rhine and Duisburg became its northernmost outpost, the city lost its political relevance, which was reflected in the fact that no German king visited Duisburg between 1016 and 1125.

Duisburg - During his stay in Duisburg in 1129, the German King Lothar decided a dispute between the Duisburg citizens and their imperial bailiff Duke Walram III. of Limburg, concerning the quarry in the Duisburg Forest, in the interests of the Duisburg citizens and against the Duke of Limburg, whose successors held the bailiwick of the imperial city of Duisburg until 1279 . From 1129 the Duisburgers used the coal sandstone quarried to build a city wall . The higher and therefore later parts of the city wall were built from tuff that was brought from the Eifel . Later renovations of the city wall consist of bricks that were burned on site.

A few months after his election as king, Friedrich I von Staufen held a court day in Dortmund in 1152. Two years later, the king was again in the Palatinate with a large retinue. Heinrich the Lion , mighty Duke of Saxony , was also present on both occasions .

The pens Eat and Become

The Essen monastery was exempted by Pope Agapitus II in 947 , that is, it was removed from the Archdiocese of Cologne and placed directly under the Pope. The monastery was thus removed from the influence of the Archbishop of Cologne . In the document of King Otto I from January 947, which is controversial in terms of authenticity , the monastery received immunity rights, the right to elect the abbess by the convention and the assurance of the property.

At the age of 22, Mathilde II , Otto I's granddaughter, became abbess in Essen in 971 after joining the monastery at the age of seventeen. Mathilde was abbess for forty years, from 971 to 1011.

The Reichshof Hatneggen (Hattingen) and its chapel are mentioned for the first time in a document from Essen Monastery in 990.

Sophia , daughter of Otto II , became abbess of Essen in 1011 and thus Mathilde II's successor.

The Benedictine Abbey of Werden received the shelf of shipping on the Ruhr from the mouth to Werden from King Konrad II in 1033 .

On the occasion of his stay in Essen , King Heinrich III. 1041 the Essen monastery had a restricted market right , according to which a fair could be held three days before and after September 27, the feast of the patron saints Cosmas and Damian.

The Essen abbess Suanhild had a parish chapel built on the Stoppenberg in 1073 ; From the 12th century onwards, this was the collegiate church of a convent of Premonstratensian women .

The community of ministers of the monastery and the citizens of the city of Essen had the Essen city wall built together in 1244.

Church buildings and foundations of monasteries

From the year 1000, the first construction phase of Romanesque churches took place, such as the Stiepeler village church or the St. Vinzentius church .

In 1122, Count Gottfried von Cappenberg founded the first Premonstratensian foundation in the German-speaking area, the Cappenberg Monastery in Selm . He handed over his castle and his property to the still young religious community. Gottfried was the last of the powerful Counts of Cappenberg . His younger brother Otto von Cappenberg was Friedrich I von Staufen's godfather . Around 1155 Otto received the famous Cappenberg head reliquary with the portrait of Friedrich as a gift from the newly crowned king.

The Kamp monastery, founded in 1123, was the first Cistercian monastery in the German-speaking area.

In 1136, Gerhard von Hochstaden gave his Hamborner property away to the Archbishop of Cologne on the condition that a Premonstratensian monastery should be built on the site of the parish church. In 1139, Archbishop Arnold I of Cologne decreed that the Hamborn Abbey did not have to pay any taxes and placed it directly under the Archbishop of Cologne. On November 11, 1157, Pope Hadrian IV took the monastery under his protection. After the reconstruction of the parish church into a monastery church and the construction of the cloister and the actual monastery, the monastery complex was consecrated in 1170 and before 1200 became an abbey.

The Order of St. John founded its first settlement on German soil in front of the walls of the city of Duisburg in 1145 and had the Marienkirche built there.

The first Cistercian convent of the Ruhr area was founded in Saarn in 1214, until today it is not clear who the founder of the monastery was.

In 1234 a Cistercian nunnery was founded in Duissern from the Kamp monastery, which was taken under his protection by the Archbishop of Cologne in November 1234. Donations made it a wealthy monastery with income from property on the right and left of the Rhine.

The former abbess of the Duissern Regenwidis monastery obtained permission from the Archbishop of Cologne in 1240 to build a Cistercian convent on her property in Bottrop-Grafenwald. In 1255 the nuns moved to the then newly built Sterkrade Monastery .

Territorial developments

The County of Altena was created in 1160 by dividing the territory of the Counts of Berg .

Around 1180, through the division of the Berg-Altena estate, the line of the Counts of Altena-Isenberg - also called Isenberg or de Novus Ponte, or Nienbrügge - and the line of the Counts of Altena-Mark - later the line is called just Mark, after their possession Mark in today's Hamm. See Burg Mark .

The Isenburg in Hattingen was completed in 1199 as a new power center of the county Isenberg an der Ruhr.

In 1225, the Archbishop of Cologne Engelbert I of Cologne was murdered by Friedrich von Isenberg . Friedrich was executed; most of the county of Isenberg an der Ruhr fell to his relatives, the Counts of the Mark. The Isenburg and Burg and city of Nienbrügge were razed. The lineage of the old Berg family became extinct in the male line, only the Isenberg and Märkische side lines continued to exist. Berg fell to Heinrich von Limburg, Irmgard von Berg's husband.

In the ham between Ahse and Lippe , the citizens of the destroyed Nienbrügge were settled by Count Adolf von der Mark from 1225 and received city rights from him in 1226 . The old Saxon field name Ham - it means angle, or describes the space between the arms that form the angle - stands in Hamm for the headland between the rivers Lippe and Ahse. Ham, which can still be found on many old maps, eventually changed over time to today's city name Hamm . From the beginning, the city was the seat of a count's court for the county of Mark , its residence and later also the main town of the county.

The Archbishops of Cologne took over rule in Vest Recklinghausen in 1228 .

During the Isenberg turmoil , from 1233 to 1243 Dietrich von Altena-Isenberg and relatives, especially the Counts von Berg from the House of Limburg and the Dukes of Limburg, fought against Count Adolf I von der Mark, Altena and Krieckenbeck, and his sons and co-regents.

In connection with a feud between Cologne and Kleve , the moated castle Strünkede in Herne was mentioned for the first time in 1243 . Since the 12th century, the knights resident there, as Ministeriale of the Counts of Kleve, were guarantors of the Klevian influence on the middle Emscher . The rule area of the Strünkeder temporarily extended from Buer in the west via Herne and Castrop to Mengede in the east.

In the same year, Adolf I. Graf von der Mark, Altena and Krickenbeck sold Krieckenbeck to his brother-in-law and ally Otto II. Graf von Geldern . In the peace treaty between Adolf I. Graf von der Mark and Altena and his opponents Dietrich von Isenberg, his relatives and others. a. The Count of Berg and the Dukes of Limburg, the son of Friedrichs von Isenberg , was granted ownership of the County of Limburg and the Krummen Grafschaft , and the Isenberg turmoil came to an end after 10 years of war. Count Adolf was able to keep his positions in the former Isenberg possession as far as possible and, in the long term, limit Dietrich von Isenberg and his descendants to a very small county.

The development of cities

Mülheim an der Ruhr was first mentioned in a document in 1093.

Duisburg - Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa granted Duisburg in 1173 the right to hold two fortnightly fairs a year at which goods could be sold free of duty. These markets were mainly used by the Flemish cloth merchants.

In Dortmund, a large wall was built around the city in 1200 . Its course is preserved in the form of the “ramparts” in the inner city area.

Recklinghausen received full city rights in 1236.

In 1240 the Dortmund council acquired a house on the market from the Count of Dortmund. For centuries it will be the city hall of the imperial city . Badly damaged by air raids in World War II in 1944 and 1945, the town hall was demolished in 1955.

Wesel was elevated to a city in September 1241. This was connected with privileges for the citizens of Wesel, including free inheritance and duty-free at all sovereign customs posts. Dietrich von Kleve also determined that the citizens of Wesel should present their disputes, which could not be decided there, to the town hall in Dortmund for a final settlement.

In 1248 the imperial cities of Dortmund and Duisburg joined the opposing king Wilhelm of Holland .

The expansion of the territories in the late Middle Ages

Strengthening the cities

The cities of Dortmund , Soest , Ahlen, Beckum, Münster and Lippstadt founded the Werner Bund on July 17, 1253 on a Lippe bridge in Werne , which the city of Osnabrück also joined on September 12, 1268. This association of cities was a forerunner of the Städtehanse. Dortmund soon assumed a leading role as a suburb of all Westphalian cities in the Hanseatic League .

Dinslaken was granted city rights by Dietrich VII. Count von Kleve in 1273 . Five years later, in 1278, Unna was granted city rights by the Count von der Mark, and in 1279 Lünen was referred to as " oppidum " (city).

The town seal of Kamen first appeared on a document in 1284. It had received municipal rights from Count Engelbert I von der Mark (1247–1277). The rights of the Kameners were based on the city rights of Dortmund and Hamm.

King Rudolf v. Habsburg pledged the city of Duisburg to the Count of Kleve in 1290. Since the pledge was no longer redeemed, Duisburg was no longer an imperial city.

Count Engelbert II von der Mark granted Bochum city rights in 1321 .

In 1340, Konrad von der Mark, Herr von Hörde, granted his village Hörde town rights with the consent of his nephew Adolf II. Count von der Mark .

From 1417 Wattenscheid had the city-like rights of freedom .

In September 1438, about half of the city of Essen burned down in a conflagration; the hospital was destroyed, the market church and minster damaged.

Buer was granted freedom on April 18, 1448 , including building a fortification and guarding the gates.

Johann II. , Duke of Kleve and Count von der Mark , issued a letter of freedom to the citizens of Castrop in 1484 . It included u. a. Civil rights, self-government and the holding of fairs. The place was fortified with a wall, a moat and three gates.

Influences of cure Cologne on the Ruhr area

In Brechte near Dortmund, the battle on the Wülferichskamp between the Prince Diocese of Paderborn and Kurköln took place in 1254 .

The Archbishop of Cologne, Konrad von Hochstaden , proclaimed a country peace in 1259, which the counties of Kleve, Jülich and Berg, among others, had to join.

The troops of the Archbishop of Cologne, Dietrich II. Von Moers, and his allies, the Duke of Jülich-Berg and the Count of Sayn, began the siege of Broich Castle in Mülheim-Broich on September 2, 1443 , which capitulated after eighteen days had to.

Limburg succession dispute 1283–1289

After the death of Duke Walrams V of Limburg , a brother of Adolf IV. Von Berg , in 1280 he left no male descendants and since his daughter Irmgard von Limburg died in 1283, who had received the fief from King Rudolf the previous year, grew up from this the Limburg succession dispute over the Duchy of Limburg . Candidates for the inheritance were the rulers of Berg and von Geldern. However, the Count von Berg sold his claims to the Duchy of Limburg to the Duke of Brabant, who now began to enforce them by force against the Gelders.

Involved in the dispute were on the side of Rainald I, Count von Geldern : Siegfried von Westerburg Archbishop of Cologne , Heinrich VI. Count of Luxembourg and John IV of Flanders, Bishop of Liège and their faithful. On the opposite side stood Johann I Duke of Brabant with his allies Engelbert I Graf von der Mark , Walram Graf von Jülich , Adolf V von Limburg Graf von Berg and Otto IV Graf von Tecklenburg , as well as the citizens of Cologne .

In 1288 the Battle of Worringen took place. The Battle of Worringen was the military final in the six-year-old Limburg succession dispute. The main opponents of the conflict were Siegfried von Westerburg , Archbishop of Cologne, and Duke Johann I von Brabant . The outcome of the battle changed the power structure in the entire north-west of Central Europe.

After the defeat of Geldern and his allies in the Battle of Worringen in 1288 north of Cologne , the Duchy of Limburg fell to the Duke of Brabant. The defeat of his ally Kurköln resulted in a weakening of the power of the Archdiocese of Cologne and the associated ducal power in Westphalia, while at the same time strengthening the power position of the counts territorial lords. In the Ruhr region this was particularly true for the Counts von Berg and von der Mark directly involved in the conflict, but indirectly also for Count von Kleve, who fought on the opposite side in the feud .

Plague and pogrom against the Jews

The medieval plague wave reached the Ruhr region in 1350. In the same year there was a pogrom against the Jewish population. In Dortmund this was expelled from the city and the property was confiscated from the city; in other cities the Jewish population was burned.

Start of hard coal mining

It must be assumed that coal was mined in the Ruhr area before, the first documentary evidence of coal mining in Dortmund dates from 1296, while the first documentary mention of coal mining in Schüren dates back to 1302.

On November 24, 1374, Duke Wilhelm von Jülich demanded a tithe on the coal mined in the Werden area.

Duisburg

After the Rhine changed its course around 1200, Duisburg was only connected to the main river via an old branch of the Rhine, which increasingly silted up in the course of the following century. Although this change in the course of the Rhine in the 13th century does not seem to have caused any major impairment of Duisburg trade, even in 1306 over 400 Duisburg Rhine ships were counted at a Rhenish customs post, but the city accounts according to the Rhine trade towards the end of the 14th century came to a standstill.

On April 29, 1248, Wilhelm of Holland pledged the imperial city of Duisburg to Walram V of Limburg , but on May 1, he confirmed the city's privileges in a document. Under the rule of Walram, the city experienced a phase of extensive independence, and in 1277 and 1278 Walram gave the city areas in the vicinity of the city, which led to an expansion of the city area.

A document dated April 6, 1280 proves the existence of a high school in Duisburg. The Landfermann-Gymnasium , which follows the tradition of this school, is one of the oldest high schools in the Ruhr area.

In 1290 Duisburg was pledged to Count Diedrich von Kleve by the German King Rudolf von Habsburg . Since the pledge was never redeemed, Duisburg became the property of the Counts of Kleve and thus de facto lost its imperial immediacy as a free imperial city.

In 1351 the city of Duisburg took part in the dispute between Duke Reinald III. von Geldern and his rebellious brother Eduard party for the rebels and received important privileges for shipping and trade in the duchy of Geldern after Edward's victory over his brother.

In order to avoid trouble with the surrounding landlords, the rule "City air makes free" did not apply in Duisburg, because the city only accepted citizens who were free. Only those in the city who were too poor to pay the membership fee (e.g. day laborers) and privileged individuals such as the Klevian Chancellor Oligschleger, who owned several houses in the city, were tolerated as free non-citizens. Non-citizens who were also unable to acquire citizenship were clergy and Jews, although from 1350 Jews were no longer tolerated in Duisburg.

Although Emperor Karl IV had made the declaration in 1362 that he wanted to keep Duisburg "forever" as a free imperial city for the rich, Count Johann von Kleve was already in possession of all imperial rights over the city of Duisburg at the beginning of 1363, which led to a dispute between the city of Duisburg and Johann von Kleve, as the city initially did not recognize the rights of Johann. This then moved the Rhine toll to Orsoy to damage the city economically. At the end of 1366 an agreement was reached between the city and the count: Johann retained nominal sovereignty over Duisburg, the judiciary and customs sovereignty.

The approval for the establishment of a customs office by Emperor Charles IV on the Homberger Werth on April 28, 1371 is considered to be the foundation of the future city of Ruhrort . In autumn 1373 the customs office was established. In a document dated February 28, 1379 by the German King Wenzel, the name "Ruhrort" appeared for the first time for the customs office at Homberger Werth.

Dortmund

The imperial city of Dortmund, whose territory was almost completely surrounded by Brandenburg property, was in a particularly difficult position, so that the Counts of Mark dominated all the roads leading to Dortmund and, since 1328, collected an annual toll from the city to transport merchants into and into Dortmund to let it out again. With the founding of the cities of Hörde (1340) and Lünen (1341), the Counts of Mark increased the pressure on Dortmund, which had to fend off repeated attacks by the Counts of Mark in the second half of the 14th century. In 1352 Dortmund survived a siege by troops from the Brandenburg region and an attempt at a surprise attack at night. In 1377 Count Wilhelm von Berg's attempt to conquer the city by bombardment and siege failed. In 1378 the attempt at a night attack on Dortmund failed, in which sympathizers of Count von Mark, who were in the city, should have opened the city gates. In the same year, Emperor Karl IV and his wife Elisabeth of Pomerania moved into the imperial city of Dortmund.

The Archdiocese of Cologne, to which Dortmund had been pledged by the respective German king in 1346 and 1376, was also interested in the possession of Dortmund, without Cologne being able to enforce the acquired rights against the city. When Count Engelbert III. von Mark with the Archbishop of Cologne Friedrich III. Allied by Saar Werden against Dortmund, the city's independence was threatened. With the arrival of the feud letter from the Archbishop of Cologne on February 21, 1388 - one day later the feud letter from Count von Mark followed - the great Dortmund feud began . In the period that followed, 47 imperial princes joined the Electoral Cologne-Mark alliance, but most of them did not intervene actively in the fighting.

Troops from the Electorate of Cologne and Brandenburg began to siege the city immediately after the letters of feud had arrived, but Dortmund had prepared for a longer siege and built up large stocks of grain. A bombardment of the city from April 17 to July 10, 1388 had to be canceled because Dortmund had meanwhile built modern powder cannons and thus fired at the opposing positions, so that the siege ring had to withdraw from the range of the guns. According to contemporary sources, it is assumed that between May 29, 1388 and November 8, 1389 about 110 troops from Dortmund took place, during which mainly the villages and farms in the Mark region were plundered. At the mediation of the city of Soest, peace was concluded on November 22, 1389. In exchange for a so-called “voluntary gift” of 7,000 guilders each to Kurköln and the Count of the Mark, they gave up all claims and demands on Dortmund.

Dortmund was able to recover relatively quickly from the high costs of warfare - a total of 60,000 guilders - as can be seen from the construction of the council choir at the Reinoldi Church in 1421 as well as from the fact that Dortmund was able to manage its own as early as 1422 To contribute as an imperial city to the financing of the Hussite campaign.

In 1403, the Wildungen Altar was the first surviving retable by the Dortmund painter Conrad von Soest to be completed.

Other cities

In a document from Count Engelbert III. The Sälzer zu Brockhausen was first mentioned by the Mark in 1389 . It is the first evidence of full-time salt production in today's Unna .

Hamm lost the residence to the city of Kleve in 1391 after the county of Mark was united with the county of Kleve. The town castle in Hamm and the ancestral seat of the count's house Burg Mark were now only the seat of the count's castle men, drosten and bailiffs. The rulers from the House of Mark ruled both countries from Kleve.

The oldest written evidence of wild horses in the Emschern lowlands is available in 1396 . The use of the stocks occurring in the Emscherbruch between Waltrop and Bottrop was a coveted privilege of the nobility.

Hattingen concluded a fortification contract with Dietrich II. Count von der Mark .

The Battle of Kleverhamm in 1397 consolidated the position of the Counts of the Mark. In the same year, Count Dietrich II von der Mark Schwerte granted full city rights.

Märkischer brother dispute 1409-1430

In 1409 Gerhard von der Mark claimed part of the paternal inheritance for the first time from his brother Adolf, Count von der Mark and Kleve . He initially received the rule of Liemers , in 1413 parts of the Sauerland in the Mark region .

In 1417, Adolf IV. Count of the Mark and, as Adolf II. Count of Kleve, was made the first Duke of Kleve by Emperor Sigismund. As a duke he is also called Adolf I. von Kleve or von Kleve-Mark.

In the following year, 1418, Adolf von der Mark, Duke of Kleve and Count von der Mark, declared that his lands Kleve and Mark were indivisible. In 1419 a feud broke out between him and his brother Gerhard von der Mark, who had been provost of Xanten's Viktorstift until 1417. The city of Duisburg refused to recognize Adolf's inheritance regulation and formed an alliance with Gerhard. Thereupon Duke Adolf and over a hundred other nobles announced the feud to the city of Duisburg. The military conflicts in 1419 and 1420 were largely limited to mutual robbery and looting, for example the Duisburg troops against Orsoy and Saarn. The feud was ended by a settlement in the autumn of 1420.

In the course of the armed conflict in the feud between the two brothers Adolf and Gerhard von der Mark, Hattingen was completely burned down in 1424, except for two houses when it was captured by Bergische troops. The city had to be rebuilt. In 1429 the Brandenburg estates recognized Gerhard as the legal lord of the county of Mark.

In 1430 Gerhard von der Mark made peace with his brother Adolf von der Mark, Duke of Kleve and Count of the Mark. He received rule over the northern part of County Mark; some important regional castles such as Blankenstein , Fredeburg , Bilstein and Volmarstein remained in the hands of Duke Adolf. Gerhard was allowed to carry the title of Count to the Mark , his brother reserved the title of von der Mark . Hamm became residence again until Gerhard von der Mark's death, Graf zur Mark.

The county of Mark under Gerhard von der Mark until 1461

On March 5, 1455, Gerhard von der Mark, Graf zur Mark, donated the Franciscan monastery in Hamm .

From 1456, Gerhard and his nephew Johann von Kleve shared control of the county of Mark.

Gerhard von der Mark, Graf zur Mark, died in 1461 and was buried in the chapel of the St. Agnes monastery when he was founded in Hamm . The magnificent brass grave plates were lost between 1939 and 1945; only a drawing of it has survived. Since Gerhard died childless, the County of Mark and the Duchy of Kleve were finally united under the reign of his nephew Johann von Kleve.

Soest feud 1444–1449

As early as 1440, the Archbishop of Cologne, Dietrich II von Moers, tried to consolidate his rule over the city of Soest. In 1441, the city then entered into an alliance with Kleve-Mark. When Soest paid homage to Duke Johann I von Kleve-Mark on June 25, 1444 and thus rejected the electoral sovereignty of the Electorate of Cologne, war broke out between the Electorate of Cologne and the Duchy of Kleve-Mark. This war was less about the city of Soest than about the dispute between Kurköln and Kleve-Mark about supremacy in Westphalia. Kurköln was supported by the diocese of Münster, the Paderborn monastery and the free imperial city of Dortmund. The vestic cities of Dorsten and Recklinghausen were the bases of the Cologne armed forces.

On the night of March 11th to March 12th, 1445, the Archbishop of Cologne advanced with an army against the city of Duisburg and hoped to be able to conquer the city in a surprise attack at night. The approaching troops were noticed and the Electoral Cologne army had to withdraw.

The Vest Recklinghausen was Archbishop of Cologne in 1446 to finance the Soest feud to the Lords of Gemen pledged.

In the same year, the stone tower was besieged and damaged during disputes on Dortmund's territory, and numerous Dortmunders were taken prisoner in the Brandenburg region.

In July 1447 the Archbishop of Cologne besieged the city of Soest unsuccessfully with his army of 8,000 Hussite mercenaries. After a fortnight bombardment of the city, the electoral Cologne army tried to storm the city walls of Soest on July 19, 1447; However, the mercenaries broke off the attack before serious fighting broke out, as there were 50 dead on the Electoral Cologne side; the city of Soest mourned 10 deaths. When the pay for the Hussite mercenaries - the archbishop was now in arrears with 200,000 guilders - was not paid even after the assault, the mercenaries withdrew on July 21st and left the archbishop with a remaining army of 4,000 men, who then started the siege had to cancel. After this failure, Archbishop Dietrich von Moers was ready to negotiate peace.

On April 27, 1449, the Soest feud was ended on the basis of the status quo with the Maastricht arbitration award, mediated by the Duke of Burgundy. Soest and Xanten came to Kleve-Mark; Kurköln received the Kaiserswerth customs post and the dominions of Fredeburg and Bilstein in the Sauerland , conquered by the troops of the Electorate of Cologne in 1444 and 1445 . This result of the Soest feud prevented a supremacy of the Electorate of Cologne in Westphalia.

Two state parliaments in Wickede decided in the spring of 1486 an extraordinary tax in the county of Mark for the sovereign Johann, Graf von der Mark and Duke von Kleve. The treasure book created for this, the Schatboick in Mark , contained a list of all taxpayers and thus listed many details on individual locations.

Dispute between the city of Essen and the Essen monastery

In October 1495 the abbess Meyna von Daun-Oberstein had to ask her canon Johann II, Duke von Kleve and Graf von Mark for help, because she had lost control of food. Although the Counts of Mark had held the bailiwick of Essen Abbey for decades, the bailiff was only elected for a certain period of time. John II took advantage of the situation and forced Abbess Meyna and her chapter to appoint him and his heirs as bailiffs. In the contract of October 21, 1495, Essen was effectively incorporated into the domain of Kleve-Mark: the abbess retained the rights of jurisdiction and administration, while military and political power passed into the hands of Kleve-Mark.

Early modern age

Urban development

Schwelm received city rights in 1496.

Fire disasters in Recklinghausen and Bochum

On April 4, 1500, a conflagration in Recklinghausen destroyed around 350 residential buildings, around half of the city, in addition to the Petruskirche, school and town hall.

The city of Bochum burned down completely on April 25, 1517. A fire that had broken out in Johann Schrivers's house spread to the surrounding thatched half-timbered houses and destroyed all the buildings in the city within one night. Schriver's assets, which had been confiscated, were nowhere near enough to rebuild the destroyed church and town hall. The reconstruction of the town hall took seven years. Although the church could be used temporarily again from 1521, its reconstruction took decades until the end of the century.

Dortmund

Since the middle of the 13th century, the city of Dortmund had increasingly bought legal titles from the Count of Dortmund. In 1320 the city acquired half of the county of Dortmund from Count Konrad Stecke . After the death of Johann Stecke, the last count of Dortmund, in 1504, the small county became the property of the city of Dortmund. On October 12, 1504, the Roman-German king and later Emperor Maximilian I enfeoffed the city of Dortmund with the county of Dortmund, which covered about 6000 hectares and to which u. a. the villages of Brechte, Körne, Eving, Holthausen and Altenmengede belonged. Since the city thus became sovereign over the county of Dortmund, the inhabitants of the county did not receive Dortmund citizenship, but remained subjects.

In 1508 the " French disease", syphilis, appeared for the first time in Dortmund, from which the entire population, including children, was severely affected. The venereal disease owes its ancient name to the fact that it has been widely spread in Europe by French mercenaries since 1498.

Territorial development in the 16th century

The period from 1500 to 1618 was characterized by considerable population growth, which benefited less the cities than the rural areas. Since the existing farms were inherited undivided to the eldest son, the number of farms remained constant. Due to the growing population, there was a high phase of Kotten formation in the Ruhr area, i. H. Kötter had to cultivate and cultivate a piece of land in the uncultivated Mark. Since the established farmers had no interest in reclaiming the Mark, they tried to keep the individual Kotten areas as small as possible, which meant that a large part of the Kotten was not viable and the Kötter also had to work as day laborers on the large farms. In the course of the sixteenth century the Dutch movement came up, i. H. In the summer Kötter worked in the economically emerging Netherlands in the field of agriculture and shipbuilding in order to support their families with the money they earned there.

Establishment of the United Duchies 1511/1521

After the death of the last Duke of Jülich, Wilhelm IV. In 1511, his son-in-law, the Hereditary Prince of Kleve-Mark Johann von der Mark , who had married Wilhelm's heir, succeeded him in the Duchies of Jülich and Berg and the County of Ravensberg . When Johann's father died in 1521, he inherited the Duchy of Kleve and the County of Mark , which resulted in the United Duchy of Jülich-Kleve-Berg .

The pledge ownership of the Counts of Holstein-Schaumburg-Gemen at Vest Recklinghausen ended in 1576 after 130 years.

Era of upheaval: Humanism and Reformation

The Reformation in the United Duchies

Although Johann III. Jülich-Kleve-Berg did not have the Worms Edict of 1521, which outlawed Luther and prohibited his writings, published in his territory; However, he stipulated on March 26, 1525 that the pastors in his countries were not allowed to spread Luther's teachings, but had to proclaim in their sermons that these teachings were heretical. He ordered that all followers of Lutheran doctrine be arrested and punished. Nevertheless, he was critical of the grievances in the Catholic Church; because on July 3, 1525 he issued a decree u. a. that the pastors of his countries had to fulfill their duties, were not allowed to take any money for church official acts, had to live in the responsible community; In order to prevent the emergence of superstitions, he banned the carrying of images of saints in processions, banned any form of ecclesiastical jurisdiction, banned monks from buying real estate and banned monks from begging in his countries.

Compared to the general development in the Reich and especially on the Reichstag on which Johann III. each from Count Wirich VI. was represented by Daun-Falkenstein , the duke tried to maintain a neutral religious policy. Under the influence of Erasmus of Rotterdam , John III. on July 18 and October 24, 1530 two ordinances on religious policy in the United Duchies, which turned against the grievances in the Catholic Church, but rejected a comprehensive Reformation. In the October version, which underlined this position again, the low level of education of the clergy was cited as the reason for the grievances.

On January 11, 1532, Duke Johann III. a church order for the duchies that reflected this neutral stance on religious issues. However, this church order was criticized by both denominations, the reforms did not go far enough for the Protestants, the Catholics criticized the “watering down” of the Catholic teaching “in the new believing sense”.

Exactly one year later, on January 11, 1533, Johann III. a "Declaratio" as a supplement to the church ordinance, which was published on April 18, 1533. In doing so, he continued to accommodate the Protestants, but fundamentally maintained religious neutrality. The Duke tried to achieve a mutual tolerance of both denominations in his countries and to prevent threatening denominational disputes.

In Mülheim an der Ruhr, the entire congregation is said to have converted to the Reformed faith three days after Easter in 1555, after - according to a list of preachers from 1744 - Johann Kremer became the first Reformed preacher in Mülheim in 1554. The first - historically proven - evangelical preacher was Johann Schöltgen, who died in 1599. The rule of Styrum remained Catholic.

The Reformation in Dortmund

In 1518/19 there was a conflict in Dortmund between the citizens and the city clergy over the privileges of the clergy . In Dortmund there were repeated disputes between traders and traders and the clergy, whose trading activities were to be restricted. As early as 1487, the city council of Dortmund allowed the clergy to import malt and grain only for their own use. In December 1518 the council banned the sale of letters of indulgence in Dortmund. In the course of the dispute that arose between the council and the clergy, the council forbade the churches to engage in trade and commerce. In return, the churches excluded all Dortmund citizens from participating in the sacraments. Easter 1519 the ban of the citizens was lifted by Cardinal Thomas Cajetan .

The disputes between the citizens of Dortmund and the city clergy continued from 1523, when citizens demanded that clergymen should be prohibited from participating in wedding celebrations and child baptisms. A compromise by the council of 1525 was short-lived, as in 1527 the guilds required the city to recruit Lutheran preachers; however, the council succeeded in preventing the guilds from converting to Protestantism.

In 1538 the small Anabaptist congregation was broken up at the instigation of the council. Two citizens of Dortmund were arrested. When one of the two preachers, Peter von Rulsem, refused to revoke the doctrine of the so-called Anabaptists, he was beheaded on January 21, 1538.

As a complement to the ecclesiastical Latin schools founded advice and citizens in Dortmund in 1543 humanistic embossed school , the Archigymnasium than higher education. The teaching facility was influenced by the models of the grammar school in Emmerich and the Paulinum in Münster. The teaching content was humanistically oriented. The first principal of the school, Johannes Lambach, shaped the intellectual and cultural life of Dortmund for over thirty years. Hermann Hamelmann and Johann Heitfeld were among the early students at the Dortmund School .

In 1556 the chaplain of St. Marien, Johann Heitfeld, began to publicly spread the Lutheran doctrine. When he ignored the advice of the council to stop this, he was expelled from Dortmund in 1557.

The "Reformer of Westphalia", Hermann Hamelmann, publicly confessed to the Reformed faith for the first time in 1553 at the Trinity Festival in Kamen; then he had to leave the city.

In 1529 the English sweat was rampant . The disease leads to death within hours of the outbreak. In Dortmund, 497 of 500 people died in the first four days of the epidemic.

Development of printing in the 16th and 17th centuries

Book printing was introduced in Wesel in 1541 and the first book was printed in Dortmund in 1544. Both cities developed into important centers of printing in the 16th and 17th centuries. From 1552 books were also printed in Unna, from 1553 also in Büderich ; however, both printing locations lost their importance in the 17th century. In 1607 the first books printed in Duisburg appeared; from 1613 books were also printed in Essen, albeit to a lesser extent. The first permanent book printing company was established in Hamm in 1650.

The "learned Duisburg" - "Duisburgum doctum"

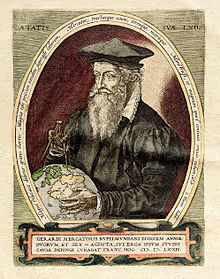

The cartographer Gerhard Mercator , born in Flanders in 1512 , settled in Duisburg in 1552 at the invitation of Duke Wilhelm the Rich , who had offered him a chair at the newly founded university. Previously persecuted by the Catholic Church, Mercator was able to continue his important work in the religiously more tolerant Duchy of Kleve.

On February 11, 1555, the city council of Duisburg decided with only one vote against to remove the statue of Salvator from the Salvatorkirche and to introduce the evangelical catechism for religious instruction. In 1558, Petrus von Benden, the first Protestant pastor, was appointed to the Salvatorkirche.

The Schola Duisburgensis became an Academic Gymnasium in Duisburg in 1559 . One of the teachers there was from 1559 to 1562 Gerhard Mercator; he taught mathematics and cosmography . The Jesuits were very critical of the planned establishment of a university in Duisburg, as they feared a university that was strongly Protestant. They initially succeeded in preventing papal approval for the establishment. Only when Duke Wilhelm V agreed to fill the chairs with Catholic professors only and to withdraw the teaching permit from Johannes Monheim, who taught in Düsseldorf , was the papal founding document issued on July 20, 1564. Two years later, Wilhelm V received the privilege of establishing the university from the Kaiser. The beginning of the Spanish-Dutch War prevented the establishment of the university, which was only founded in 1655 under Prussian rule.

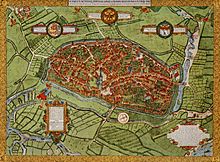

The Mercator student Johannes Corputius recorded the view of Duisburg in an exact plan for the first time in 1566 .

Effects of the Eighty Years War on the Ruhr Area

With the revolt of the Dutch provinces against Spanish rule in 1568, the Netherlands began their struggle for independence, known as the " Eighty Years War " (1568–1648). The fighting repeatedly spread to the Ruhr area, with the western Ruhr area being particularly affected. Parts of the region were occupied by Spanish troops in the winter of 1598/99 . Viewed from the Lower Rhine perspective, the armed conflicts that took place during this period, such as the Truchsessian War or the Thirty Years' War, were only phases within a series of battles in the Lower Rhine and Ruhr area that stretched over almost eighty years.

Truchsessian War 1583–1589

Through the Cologne War, more precisely the Truchsessian War, the Ruhr area was drawn into the military conflicts of the Eighty Years War. On December 5, 1577, Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg was elected Archbishop of Cologne and thus elector against the resistance of the emperor and the Spanish king. His marriage to Countess Agnes von Mansfeld in 1582 and his conversion to Protestantism prompted him - not least due to pressure from the Calvinist Counts of the Rhineland - to attempt to convert the Catholic Archdiocese of Cologne into a hereditary Protestant duchy, which would have led to a two-thirds majority in the Kurkolleg and Influence on the choice of the German king. In edicts of December 19, 1582, January 16 and February 2, 1583, he left the residents of Kurköln free to choose their religion themselves. On March 22, 1583, Gebhard was removed from his office as archbishop by a papal bull, and on May 23, 1583 Ernst von Bayern was elected as his successor. After defeats by the Bavarian and Spanish troops, Gebhard had to flee to the Electoral Cologne Duchy of Westphalia, where he resided in Werl.

In 1583 the Spanish general Francisco de Mendoza advanced with 21,000 foot soldiers and 2,500 riders to Orsoy and set up a camp with entrenchments in Walsum . At the beginning of 1584, the advance of Spanish troops into the right bank of the Rhine began; here in 1584 the villages of Meiderich and Lakum were looted. As they continued to advance, the Spanish troops occupied Essen and the surrounding villages, pillaged and pillaged the Essen area.

Further defeats of his troops prompted Gebhard to flee to the territory of the Netherlands in the spring of 1584 with a few remaining riders, where he found acceptance and support. At the national level, the Truchsessian War was over, but not from the point of view of the Ruhr area; for now this region was drawn into the military conflicts of the Eighty Years War.

The mercenary leader Martin Schenk von Nideggen , who was in the service of the Netherlands at the time, occupied the Rheinberg in 1586 with his mercenary troops, placed a strong garrison in the city and supplied the troops stationed there with ample provisions so that the city against the advancing ones Spanish troops under Alessandro Farnese , Prince of Parma and Spanish governor in the Netherlands, could be defended. Although Ruhrort belonged to the Duchy of Kleve, Nideggen succeeded in smuggling mercenaries into the city of Ruhrort on the night of January 26, 1587 and seizing the city. Afterwards the nunnery in Duisburg-Duissern and the Premonstratensian monastery in Hamborn were burned down by Nideggen's mercenaries.

The Dutch occupied Ruhrort was captured on March 26, 1587 in the Eighty Years' War by Spanish troops after a siege; the Spanish troops stayed until 1589.

The Eighty Years War from 1598 to 1609

After a few years of relative peace, during which it was possible to keep the Ruhr area on the right bank of the Rhine largely out of the fighting of the Eighty Years' War, the war spread to the Ruhr area again from 1598.

In 1598, the Spaniards moved troops to Vest Recklinghausen and the County of Mark. Recklinghausen was captured by General Francisco de Mendoza and his 24,000 soldiers .

In today's Mülheim an der Ruhr, Broich Castle was captured on October 9, 1598 after a siege by Spanish mercenary troops with a strength of 5,000 on the orders of Francisco de Mendoza; the entire castle crew - including the women and children - was massacred, the lord of the castle von Broich, Count Wirich VI , who was captured in Spanish captivity . von Daun-Falkenstein , murdered on October 11th.

Essen was occupied by Spanish troops on December 20, 1598, who sacked the area of the Essen monastery and the Werden Abbey. Spanish troops were quartered in the city of Essen and wintered in the city. In April 1599 the troops withdrew in exchange for payment of “Zehrgeld”. As a result of the occupation of Essen by the Spanish garrison, the plague broke out in the city.

Spanish troops were quartered in the city of Dortmund in 1598 and 1599; the surrounding area was looted. Castrop , for example, suffered badly from the looting. Because of the Spanish troop accommodation, there was a food shortage.

In the course of a state-Dutch campaign on the Lower Rhine led by Moritz von Orange, Moers and Rheinberg were captured in 1601; the Dutch mercenaries also judged in the Ruhr area on the right bank of the Rhine. B. in Walsum , damage.

In the course of the Eighty Years' War, a Spanish army of 20,000 mercenaries under Ambrosio Spinola camped at the mouth of the Ruhr near Ruhrort in 1605 . From there Spinola had the town of Mülheim and Broich Castle occupied by troops. The state troops camped at Wesel under Moritz von Oranien attacked the Spanish troops and defeated them in the battle of Mülheim . At the news that the main Spanish army was approaching, the state troops withdrew, and Mülheim remained under Spanish occupation until 1609, when state troops drove the occupation out in the second battle .

On April 12, 1609, the Netherlands and Spain agreed in Antwerp on an armistice that lasted twelve years, until the Eighty Years War flared up again in connection with the Thirty Years War.

Jülich-Klevian succession dispute 1609–1614

After Duke Johann Wilhelm died on March 25, 1609, the Jülich-Klevische inheritance dispute began , the dispute over his inheritance, which consisted of the duchies of Kleve, Jülich, Berg and the counties of Mark and Ravensburg. On June 10 , after their troops had occupied the states , Brandenburg and Pfalz-Neuburg jointly took over the administration of the areas in accordance with the Dortmund Treaty . With the interference of Emperor Rudolf II, who did not recognize the annexation of the countries, and the resulting interference by France, Spain and the Netherlands, the regional conflict threatened to escalate into a European war at times. The conflict was defused by the conversion of Wolfgang-Wilhelm von Pfalz-Neuburg to Catholicism and his marriage to the sister of the Bavarian elector. In the Treaty of Xanten on November 12, 1614, an agreement was reached on a division of the inheritance: the Duchies of Jülich and Berg came to the Palatinate-Neuburg family, the Duchy of Kleve and the Counties of Mark and Ravensberg became Brandenburg-Prussian .

Thirty Years War 1618–1648

From the point of view of the western Ruhr area and the Lower Rhine, the Thirty Years War was only a new phase of the Eighty Years War, which had been fought for decades in the western Ruhr area. In the course of the Thirty Years' War, the central and eastern Ruhr areas became theaters of war. So the rich Dortmund was taken repeatedly and forced to pay large amounts of money to the Catholic and Protestant armies. The city will no longer reach its old size until industrialization. On the Lower Rhine, Duisburg and Wesel were alternately occupied by Dutch and Spanish troops. Essen was no different . Hamm was first occupied by Spanish troops of the Catholic League in 1622, replaced by Protestant Hessians and Swedes in 1633 and finally again conquered by imperial troops in 1636 .

Even before the Thirty Years War were in Essen muskets made. While 2700 muskets were produced in 1608, rifle production, the most important branch of industry in Essen at that time, flourished during the war, production rose to 14,800 in 1620 and even in the decade 1632 to 1642 the annual production was always between 5000 and 7000 pieces.

In 1621 the armistice, which had interrupted the Eighty Years War between Spain and the States General, expired and in the spring of 1622 Spanish troops began their attack down the Rhine. The first war taxes began. General Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba and his 10,000 soldiers moved into winter quarters in the northern county of Mark. Christian von Braunschweig appeared with 10,000 men. After Tilly's victory on July 27, 1623 at Stadtlohn over Christian von Braunschweig's troops, the state troops withdrew from the County of Mark and only occupied Lünen, Unna and Kamen.

Dortmund was in a particularly difficult situation because it was a Protestant city, but as an imperial city it was directly subordinate to the Catholic German king. The city tried to pursue a neutral policy between the denominational camps, which went so far that in 1625 the city council threatened all citizens with the loss of their civil rights if they were to be recruited as mercenaries.

In the years 1621 to 1624 Duisburg was occupied one after the other by Spanish or Spanish service Italian and various German mercenary troops as well as by Palatinate-Neuburg troops, who had to be fed by the city and tried to enrich themselves at the expense of the city and the citizens .

After Maria Clara von Spaur, Pflaum and Valör , the abbess of Essen, who fled the Protestant troops to Cologne in 1627, obtained an edict from Emperor Ferdinand II that the city of Essen should come under ecclesiastical sovereignty again April 5 Italian mercenaries deployed by Spain entered the city to assert the interests of the abbess. The citizens of Essen were disarmed on May 1st, and on May 6th the abbess symbolically took possession of the market church, which had been Protestant until then. After the citizens of Essen had received an edict from the emperor on August 27th that the foreign troops were to be withdrawn and the damage caused to the city to be compensated, the abbess deposed the council of Essen on September 9 and appointed catholic ones instead Council members who officially declared on November 13th that Essen would renounce the status of an imperial-free city. The Italian troops withdrew in April 1629.

In October 1628 state troops under the command of the Count of Styrum conquered Ratingen and sacked the city. In June 1629 the Spanish troops massed in the Duchy of Berg, 30 companies alone were billeted in Mülheim. After the Dutch troops had succeeded in conquering Wesel on August 19, 1629, the Spaniards withdrew and state troops occupied the Duchy of Berg.

In 1632 the fighting again spread to the Ruhr area. Gottfried Heinrich Graf zu Pappenheim occupied Dortmund with Catholic troops and waived the burning down of the imperial city in return for a ransom. 70 noble houses were looted on his way through the county of Mark. The troops of the league were stationed in Dortmund until January 17, 1633, when the city bought itself free from the occupation in return for payment of 20,000 Reichstalers. No sooner had the troops of the Catholic League left the city than the citizens opened the city to troops from the Protestant Landgrave Wilhelm von Hessen. During the more than three years of occupation of the city by Hessian troops, the population suffered from constant attacks by soldiers. After a week-long siege, imperial troops captured the city in 1636. The citizens were disarmed, all grain stores were confiscated and the city had to pay high contributions, which caused many residents to leave Dortmund.

From Dortmund, the Hessian troops advanced westward in 1633 and occupied Dorsten, which was their main base of operations until 1641, and Ruhrort. The city of Duisburg was able to buy itself free from an occupation through deliveries in kind and cash payments. In the meantime, Dutch troops, who had already controlled the Lower Rhine from Wesel onwards, occupied Orsoy in 1632 and Rheinberg in 1633. In order to better control the Lower Rhine, the Dutch occupied Duisburg in February 1636, whose neutrality had previously been accepted by the warring parties. When the Dutch occupation had not yet withdrawn in 1638, Spain canceled the neutrality agreement, which meant that the years 1638 to 1645 were the most difficult for the Duisburg area during the war. Since the Dutch occupation was too weak to repel a surprise attack, let alone to control the area around the city, only one city gate was kept open. Since the Spaniards controlled the area around Duisburg, agricultural activities in the immediate vicinity of the city could only take place under the protection of larger military units. When the Dutch troops withdrew in June 1644 and Brandenburg troops occupied Duisburg, the Spaniards declared Duisburg a neutral area again in early 1645.

Hattingen was taken in 1635 by the Swedish Colonel Wilhelm Wendt zum Crassenstein with 3,000 soldiers.

The Peace of Westphalia was signed in 1648. This formally ended both the Thirty and the Eighty Years War.

In order to secure the payment of a total of 5 million thalers across the empire to Sweden, the imperial city of Dortmund, which had signed the peace treaty, remained for two more years until large sums of money were paid by Swedish troops who were quartered in the county of Dortmund and imperial troops who were based in the City of Dortmund had occupied. After the demands were met, the Swedish troops withdrew on April 4, 1650 and the imperial troops on July 27, 1650. In Duisburg, which was occupied by Brandenburg troops, Swedish troops were also billeted from April 1649 to November 1650 through the enforcement of the fixed payments to Sweden.

Dutch troops were also present on the Lower Rhine for a long time.

Witch hunt

In Dortmund in 1451 a woman was buried alive under the gallows as an alleged sorceress . In 1513, eight people were burned as magicians near Walsum . In 1514 a woman accused of witchcraft was executed on the Segensberg in Hochlar . Drost Graf von Schaumburg had the defendant accused of causing a cold winter.

In Duisburg a witch trial in 1536 took a fair course. When a woman Wetzel was accused of milk magic , she was a Molketoeversche , the denouncer, Mrs. Angerhausen, was condemned as a slanderer. She therefore had to carry 3,000 stones to the market. In Duisburg in October 1561 Agnes Muiseltz was suspected of witchcraft, tortured and subjected to a water test in the Ruhr .

The witch trials in Vest Recklinghausen reached a high point in 1580 and 1581. Places of execution were on the Segensberg in Hochlar and on the Stimberg in the Haard near Oer . 44 people, mostly women, were burned at the stake. In 1650 Trine Plump resisted torture.

At the same time, six women and one man fell victim to the witch craze in Märkisches Witten . In 1647, the farmer Arndt Bottermann from Witten was found guilty and executed in a sorcery trial . The case of Arndt Bottermann is one of the few trials that took place in Grafschaft Mark .

Anna Coesters from Dortmund was subjected to the water test at the Kuckelkenmühlenteich in 1581. Because she was floating on the water, she was charged with sorcery, tortured, and eventually burned. In the same year four other people in the county of Dortmund were beheaded for alleged magic.

In 1593, for the first time since 1581, there was another chain of charges and executions for sorcery and witchcraft in Dortmund, which killed 15 people in the course of the year. From the end of 1593, no further witch trials took place in Dortmund.

In the freedom Horst an der Emscher - today a district of Gelsenkirchen - there was a witch trial in 1609, which would have killed almost an entire family. The daughter of the farmer Johann Notthoff and his wife Hille reported to the responsible judge at Schloss Horst that her father was accused of sorcery in rumors circulating in the village. Johann Notthoff volunteered, along with some other accused, a short time later for a water test in the mill pond. Two residents who had spread the rumors also had to undergo this test. Despite being tied up, all swam on the surface of the water, which was taken as evidence of witchcraft. As a control, a bystander was also thrown into the water, which sank but was rescued. In order to free themselves from the accusation of witchcraft, Johann Notthoff's wife and children immediately reported for a water test; everyone swam upstairs and was taken to the cellar dungeons of Schloss Horst for further interrogation. This interrogation was initially amicable, then “embarrassing”, that is, with torture. The parents as well as the 13- and 14-year-old children confessed to witchcraft, dance and fornication with the devil. They also named a number of accomplices. Hille Notthoff's attempt to escape failed; it was picked up again a day later. She and the other accused were sentenced to death. Johann and Hille Notthoff were first strangled, then their bodies were burned. The underage children were pardoned by the lord of the castle Dietrich von der Recke and entrusted to a Christian family for care and re-education. Four years later, Röttger Schniering, a farmer from neighboring Brauck , whose name had been mentioned during the interrogations in 1609 and who has therefore also been exposed to numerous rumors since then, volunteered to take a water test at Horster Richter. He also swam upstairs and was arrested and interrogated under torture. He too confessed and was executed.

In the Thirty Years' War, which began a little later, the witch hunt in Central Europe reached a climax. Many witch trials took place in Westphalia too. In 1629, 30 people were victims of the witch hunt in the Werne office .

The last of a total of 130 witch trials since 1514 took place in 1706 in Vest Recklinghausen in Cologne . Trine Plumpe resisted torture in a witch trial in 1650 and thus contributed to the end of the witch hunt in the immediate jurisdiction of the Vests Recklinghausen.

Beginnings of mining

The earliest regulation of mining in the Ruhr area is the Jülich-Clevische Bergordnung, which was issued on April 24, 1542 and remained in force until around 1750. Since the sovereign had the mountain shelf, it was stipulated that this right could be granted for certain mine fields against payment of the mountain tithe.

For Steele , high-yield coal mines were named in the town book of Bruyn and Hugenberg in 1576 .

The oldest mention of mining in Witten comes from the year 1578, when the landlords of Haus Berge and Burg Steinhausen agreed that coal mining should be restricted because of the devastation that had been caused and that no more coal should be extracted than the city of Witten consumed.