Electorate of Saxony

|

Territory in the Holy Roman Empire |

|

|---|---|

| Electorate of Saxony | |

| coat of arms | |

|

|

| map | |

|

|

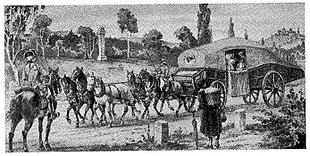

| The Electorate of Saxony after the division of Leipzig in 1485: The "Ernestine" countries are in red, the "Albertine" countries in yellow. From 1485 to 1547 the electoral dignity lay with the Ernestine line, so that only their countries (red) constituted an electorate during this period. Although the rule of Beeskow and Storkow and the Duchy of Sagan were designated as common property in the Leipzig Treaty , the Ernestine Elector denied the rule for himself until 1518; the Albertine ruler had been the Duke of Sagan since 1472. The Sorau rule was lost in 1512.

|

|

| Consist | 1356-1806 |

| Arose from | Hzg. Saxony-Wittenberg |

| Form of rule | Electorate |

| Ruler / government | Elector |

| Today's region / s | DE-SN , DE-ST , DE-BB , DE-TH , DE-BY , PL |

| Parliament | Elector Council & Imperial Council |

| Reichskreis | Upper Saxon Imperial Circle |

| Capitals / residences |

Wittenberg until 1547, then Dresden temporarily Meißen (15th century), Torgau (16th century) |

| Dynasties | Ascanians , Wettins |

| Denomination / Religions |

Catholic until 1525/1527, then Lutheran

|

| Incorporated into |

Kingdom of Saxony , Saxon duchies

|

The Electorate of Saxony , also briefly Electorate or Chur Saxony , was a territory of the Holy Roman Empire .

In 1356 the Duchy of Saxony-Wittenberg was named one of the Courlands by Emperor Charles IV in the Golden Bull . From then on, the Ascanians provided an elector. After the Saxon-Wittenberg line of the Ascanians in the male line died out in 1422, the Roman-German King Sigismund enfeoffed the Meissnian Margrave Frederick the Quarrel from the Wettin line with the duchy in 1423, whereby the Saxon electoral dignity also passed to them in 1423. Due to the electoral dignity of the ruler, the name was subsequently usedElectorate of Saxony also used for the Meissnian and Thuringian possessions of the Wettins, although the electoral dignity was only linked to part of the electoral territories, the Kurlande. In the case of the Saxon Electorate, this was the Kurkreis , the area of the former Duchy of Saxony-Wittenberg.

In the Leipzig Treaty of 1485 , the division of the Wettin noble house into the Ernestine line and the Albertine line was agreed, with the Kurkreis going to the Ernestines . In 1547, during the Wittenberg surrender, the district and electoral dignity fell to Duke Moritz of the Albertine line. The Albertines remained electors until the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 and then achieved the dignity of Saxony through an alliance with Napoleon . The Electorate of Saxony became the Kingdom of Saxony , a member state of the Rhine Confederation .

The country developed an administration that was strong and effective for this period ; it had a diversified economy and high prosperity at the same time . Socially, the bourgeois structures remained behind in comparison to the western states at that time, for example in the states- general , and were restricted in their development by the nobility and the administration. In return, the Reformation that emanated from Saxony provided important humanistic and educational impulses. Culture and the arts flourished in the 18th century.

In the early modern period the electorate was the second most important territory and protective power of the Protestant principalities in the Holy Roman Empire for about 200 years until the end of the 17th century . At the time of its greatest expansion in 1807 (a year after it was made a kingdom), Saxony was 636.25 square miles , which is the equivalent of 34,993.75 square kilometers , and reached a population of 2.010 million.

Historical geography

Political geography

There has never been a territorially consolidated Electoral Saxony. The territorial structure was constantly changing through the purchase and sale of offices, the division of inheritance and inheritance , war losses and gains. From 1356 to 1422 the electorate consisted only of the area around Wittenberg. By assuming the electoral dignity of the Meissen margrave in 1422, the territorial area of the Electorate of Saxony expanded and extended into the Vogtland and the Elbe Sandstone Mountains. In the Thirty Years' War the two Lausitzes were incorporated into the state association. As a result, the state area expanded again considerably and included the areas further east along the Oder and Neisse rivers. In 1547, after the Wittenberg surrender in Thuringia , larger parts were permanently lost to Electoral Saxony.

According to the political borders of 1550, Saxony was bordered in the south and east by the Kingdom of Bohemia , which was ruled by the Habsburgs , by the Margraviate of Niederlausitz , the Margraviate of Upper Lusatia and in the north by the emerging Brandenburg. In the southwest, Saxony bordered the Principality of Bayreuth and the Bamberg Monastery . In the west it bordered the Landgraviate of Hesse and the Principality of Anhalt . There were also some smaller counties and principalities in the border area. Saxony itself had a very irregularly structured border in the west. There were also individual enclaves within Saxony. In 1635 a closed territory was annexed with the two Lausitzes, since then Saxony bordered on the Habsburg ruled Silesia .

Landscape structure

The landscapes of Kursachsen ranged from the North German lowlands to the German low mountain range , the vegetation from barren heather vegetation to mixed forest . The natural spatial structure divides the Saxon state into three large zones:

- the Saxon mountainous and low mountain range ,

- the Saxon loess area including today's southern Saxony-Anhalt

- and the north Saxon plains including today's south Brandenburg and east Saxony-Anhalt areas .

A large part of the population lived in the low mountain range, the area around Annaberg and Freiberg in the Ore Mountains was the most densely populated . The soil was not very productive for agricultural use. Instead, trades, factories and mines dominated. In southern Saxony, the historical Vogtland , and Upper Lusatia with the Zittau Mountains , the Lusatian Bergland , and Saxon Switzerland are spatially striking differentiations of the Electoral Saxon territory.

Central Saxony is divided into the Leipzig lowland bay , the Saxon Elbland and the central Saxon hill country . The middle zone of Saxony was very heavily used agriculturally and was a supra-regional traffic hub with the centers Leipzig and Dresden. The Leipzig area developed into the second center in Saxony after Dresden.

Historic landscape zones and natural spaces in the northern area of Kursachsen are the Fläming , the Spreewald , the Lower Lusatia with the Lusatian border wall . The former center of Saxony around Wittenberg to Torgau was initially just as densely populated as the Elbe basin, for example, but after 1547 it fell significantly behind in development, while the Dresden area increased significantly in population. The northern area was therefore not very productive, both agriculturally and commercially, and was generally less populated than the southern parts of the country. Larger settlements were rare.

The main river of the Electorate of Saxony was the Elbe with the Saale as the longest tributary. Other waterways were the Black Elster , the Neisse and the White Elster .

Anthropogeographical influences

Electoral Saxony has been a country rich in natural resources, so that a heterogeneous production division in mining along the low mountain range in the south of Electoral Saxony, the Ore Mountains , was formed at an early stage . In addition to silver, copper and tin ores , iron , cobalt and tungsten have been mined there since the end of the Middle Ages . Lime has been mined in the Lengefeld lime works since 1528, limestone has been mined in the Maxen lime mining area since 1546, and in Borna lime mining has been produced since 1551. From there, marble was also made, among other thingsfor the expansion of the Dresden Residence. The Crottendorf lime works had been supplying marble since 1587, and the Hammerunterwiesenthal lime works and the Hermsdorf lime works also produced marble. The importance of mining for the Saxon economy rose sharply in the 16th century, so that Kursachsen had one of the most important mining areas in Europe after a long period of growth . Negative effects on the landscape from mining were mainly evident from logging in the forests of the Ore Mountains. The wood was used to fire the smelters in order to extract ore and silver from the ore rock of the mines .

The Elbe Sandstone Mountains were an important supplier of building materials for the Saxon residences. Sandstone has a significant impact on Dresden's old town and new town . The table mountains were also used as a fortress. The fortress Koenigstein is one such example. Lusatian granite was mainly extracted in many quarries in Upper Lusatia, especially West Lusatia. The anthropological impact of the Electoral Saxon period was significant in terms of landscape, as were the many artificial ditches such as the Pechöfer ditch, which were built to operate the many mines. Other important infrastructure buildings from the time of the electorate that still exist today are:

- Ore Canal in the Freiberg northern district

- Neugraben (large gallows pond)

- New dig rafts

- Elsterfloßgraben

- Cross trench

- Altväterbrücke

The soil values and also the moderate Central European climate made a generally extensive agriculture possible in the course axes outside the southern mountain zone.

The traffic-side penetration of the area was problematic in the premodern times, as paths and river crossings and precise directories had only low standards. To overcome the rivers, an officially regulated bridge was built in Saxony at an early stage . Many of these bridges are still in use today.

Territorial inventory changes

The Wettins made it possible for their later sons to form secondary lines within the entire house. These so-called secundogenitures did not mean a division of the country , because after the extinction of the favored line they fell back to the main line . In Saxony there were at times the following branch lines:

- Saxony-Weißenfels from 1656/57 to 1746

- Saxony-Zeitz from 1656/57 to 1718

- Saxony-Merseburg from 1656/57 to 1738

In this list, these countries are not included in the overall heritage of Saxony in terms of area.

- In 1697 the Quedlinburg inheritance , the Petersberg and three offices were sold to Brandenburg-Prussia (circumference 2 geographical square miles of 7,420,439 meters, 110 square kilometers).

- 1718 the succession of the lands of the Zeitz line followed (circumference 62.28 square miles, 3429.3 square kilometers).

- In 1736, Saxony received the offices of Landeck , Frauensee and the Hessian part of Treffurt (area 5.10 square miles, 280.8 square kilometers) to compensate for its claims on Hanau .

- In 1737 the lands of the line from Merseburg to Saxony (circumference 96.90 square miles, 5335.6 square kilometers) fell by inheritance .

- In 1743 Landeck and Frauensee were sold to Hessen-Kassel (circumference 5 square miles, 275.3 square kilometers).

- In 1746 the states of the Weißenfels line fell to Saxony (circumference 60.75 square miles, 3345 square kilometers).

- In 1780 half the Mansfeld was added (circumference 8.50 square miles, 468 square kilometers).

Already as a kingdom:

- In 1807, as a result of the Fourth Coalition War , Saxony received the Cottbus District of Prussia (circumference 20 square miles, 1101 square kilometers).

- In 1808, Saxony ceded most of Mansfeld, Treffurt, Dorla , Barby and Gommern to the Kingdom of Westphalia (6.5 square miles, 357.9 square kilometers).

In 1807, Albertine Saxony, which was elevated to a kingdom a year earlier, comprised the territorial maximum of 636.25 square miles, 34,993.75 square kilometers.

| unit | 1694 | 1733 | 1763 | 1807 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Square mile | 398.22 | 458.5 | 616.25 | 636.25 |

| Square kilometre | 21,902.1 | 25,217.5 | 33,893.75 | 34,993.75 |

population

The article section on the population of the Electorate of Saxony is divided into a statistical complex of topics and a social-historical section.

The statistical section evaluates the changes in the population based on numbers and analyzes the formation of the classes and social structures . The relationship between the city and the surrounding area, the regional distribution of the inhabitants, the social gradient, population increases or decreases are also examined in the article section.

In the social history section, the areas of education, research, health and social issues are considered. These topics have become policy fields in today's world. In the early modern period, these social issues were not in the focus of government considerations, as there were no formal rights of co-determination of the masses. At the same time, these soft fields caused the development of the population and thus of society, since they had a direct impact on people's daily life and stimulated the development of more humane forms of life, which resulted in changes in life forms .

Population development

Since the High Middle Ages, the state area has been increasingly populated by German-speaking people as part of the eastern settlement . The Sorbian - speaking pre-population was linguistically assimilated in most areas over time. Settlement increased rapidly and urban structures formed. Economy and trade developed. By 1600, Electoral Saxony had around 750,000 inhabitants. Compared to other imperial territories of this time, Kursachsen was in the front area with its population number. The most heavily populated areas were the Habsburg lands, which had a total population of 5.8 million, of which two million were in the Habsburg hereditary lands alonelived. The second largest territory in terms of inhabitants was the Electorate of Bavaria with one million inhabitants. Saxony followed in third place, ahead of the Electorate of Brandenburg and the Duchy of Württemberg , each with 450,000 inhabitants.

During the early modern period, external environmental influences led to sometimes drastic fluctuations in the population. War casualties among the civilian population occurred primarily in the Thirty Years' Warcaused by fighting, epidemics, hunger and acts of violence by armies passing through. Saxony actively participated in the Thirty Years' War in 1631, as a result of which foreign armies also crossed the country and engaged in combat operations. The population losses of the Thirty Years War are estimated at around 400,000 people. This affects the losses actually incurred and the resulting loss of birth. It took 90 years for Saxony to regain its pre-war population. In the Seven Years' War from 1755 to 1763, Saxony was occupied by Prussia and again a theater of war. This also led to high casualties among the civilian population. Further fluctuations were caused by short-term events such as epidemics. These occurred during the entire time of the electorate and led to high mortality rates in the population. The last plague, which also claimed the most victims, raged from spring 1680 to January 1681.

Such fluctuations were partially offset by migration movements. A large part of the Protestants expelled from Bohemia during the Habsburg Counter-Reformation emigrated to neighboring Saxony. An estimated 50,000 to 80,000 exiles settled in the Electorate of Saxony between the start of emigration in 1620 and Emperor Joseph II's patent of tolerance in 1781. Despite the high mortality and the effects of the war, the population increased and doubled from 1600 to 1805 to two million inhabitants. Of these, 1,849,400 were considered to be German-speaking. About 160,000 Sorbs lived in Lusatiawho cultivated their own culture and language. The number of Jews who were only tolerated in some cities is given as 600 for this year (1768: 459).

The population density of Saxony was around 50 inhabitants per square kilometer in 1800, which was considered a densely populated area at the time. Alongside Württemberg, Kursachsen was the most densely populated German state, with a population density similar to that of the Netherlands. While there were 2,150 inhabitants per square mile in the Netherlands, this was around 1,700 in Kursachsen in 2017. Brandenburg-Prussia had only 919 inhabitants per square mile.

| year | 1755 | 1763 | 1772 | 1780 | 1795 | 1798 | 1799 | 1802 | 1805 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residents | 1,686,908 | 1,635,000 | 1,632,660 | 1,843,260 | 1,925,695 | 1,962,790 | 1,980,790 | 1,997,508 | 2,010,000 |

According to other data, the population developed as follows (in round thousands):

| year | 1608 | 1612 | 1630 | 1645 | 1720 | 1755 | 1772 | 1790 | 1800 | 1805 | 1810 | 1814 | 1815 | 1820 | 1829 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residents | 845 | 932 | 1500 | 1000 | 1500 | 1695 | 1633 | 1885 | 1976 | 2052 | 2055 | 1946 | 1179 | 1249 | 1397 |

Corporate structure

The society of the Electorate of Saxony was premodern . Many medieval structures and orders lasted until the end of the electorate. The most important form of social structure was the division of society into classes of different sizes. The smallest in number was the second estate, which in 1805 had 7600 people. It was made up of nobles and the civil servants of the Electoral Saxon administration. In addition to the high nobility , which was formed in Saxony by the Wettins, there was the land nobility and the court nobility . The landed gentry continued to maintain manors. Around 1750 there were about 800 manorial and official manors. As of August 2017, a total of 233 Saxon noble families have been recorded and categorized in Wikipedia (see category: Saxon noble family ). In 1805, 16,706 people belonged to the next largest first estate, made up of spiritual dignitaries and teachers of the lower clergy . The exact size of the third estate, made up of citizens and free farmers, is not known exactly, but around 1805 the number of citizens and townspeople was 592,000, and that of peasants and country people was 1,342,703.

Socially, Saxony was far superior to its neighbors in the north, but also to the Habsburg territorial complex in the south. It had an economically active citizenry, a high level of education compared to the time, and very heterogeneous social structures. In the north of the state territory the conditions were more similar to those of Brandenburg. There was a powerful manorial rule and an extremely strong medieval feudal and religious system in the country. Cities in Saxony did not have an easy time with the landlords either, but they were able to develop at least partially autonomous structures and assert themselves if they obtained patrimonial jurisdiction .

The social development in Saxony was pushed more directly from above and not from the middle. The middle formed the citizens. In this way Saxony differed from England or Holland, where a strongly developed bourgeoisie could defy feudal professional rights. The Leipzig merchant class did not succeed in this with respect to the aristocratic associations. The bourgeoisie remained integrated into the feudal state and got involved in its structures. Saxony was superior in the area of social liberalization and stimulated the European East in its own development, especially Poland-Lithuania . Opposite the progressive centers of the 18th century, the Île-de-France, Holland and England, but Saxony also lagged behind. However, it quickly adapted the developments there and adapted the models to its own needs. This applied to all social issues.

Settlement structure

The territory of Saxony was unevenly populated regionally, but was criss-crossed by a network of cities since the end of the Middle Ages. Several trade , production and agricultural centers were formed. There were trading cities mainly at transport hubs or along important trade routes. Leipzig was such an early, large trading center with supraregional importance. The most important urban centers of Upper Lusatia, which were incorporated into the electorate in 1636, had been formed in the Upper Lusatian Six- City League since the Middle Ages . The city of Görlitz stood out from this alliance as the largest and most important trading city. Immigration andPopulation growth took place mainly in the Ore Mountains in the area around Freiberg , Plauen and Annaberg .

There the economic activity opportunities through mining were higher than, for example, in North Saxon areas, which had unproductive soils for agriculture. In addition to the production and commercial towns, small farming towns formed everywhere , such as Annaburg , Prettin , Schweinitz , Bad Schmiedeberg or Seyda, all of which were located in the Kurkreis and in the early modern period had between 800 and 1500 inhabitants. They were often official seats and contact points for several dozen settlements, farms or colonies. The five agricultural towns mentioned were each 10 to 15 kilometers apart. From the 16th century onwards, there was a dense and closed city network of basic centers throughout Saxony.

Around 1500 there were around 150 places with city rights in Saxony , in which around a third of the population lived. From this number, however, no corresponding form of urban settlement for these places can be derived, because at the time of the Reformation there was no city with more than 10,000 inhabitants in Saxony. The cities had a closed settlement core and usually an external fortification. The market square , a town hall and a princely residence building were among the basic forms of urban planning structures. These formed the basis of the urban architecture , on which the buildings of the often representative town houses were based .

Approximately exact figures for the individual cities can be reconstructed via the tax register. Around the year 1550 Leipzig and Freiberg had around 7500, Zwickau 7000, Dresden 6500, Annaberg 5500, Chemnitz 4000 and Marienberg 4000 inhabitants. 95 so-called cities had fewer than 100 inhabitants and around 50 cities had more than 1,000 inhabitants. These figures show how small-town the urban landscape of Saxony was. The effects of the cities on their surrounding areas were not yet very large. Transport and relationships between cities were far less pronounced than during the industrialization period.

In 1805 there were 20 cities with more than 5000 inhabitants in Saxony. The largest cities in the Electorate of Saxony around 1800 were firstly Dresden with 55,181 inhabitants, secondly Leipzig with 30,796 inhabitants. Chemnitz follows in third place with 10,835 inhabitants. These numbers are not very high in comparison to Western European cities such as Flanders , Holland or England . With the exception of Dresden and Leipzig, around 1800 there were only small towns in the Electorate of Saxony. Nevertheless, there has been a demonstrable growth in the urban landscape of Saxony, because at the time of the Reformation only five cities in Saxony had larger than 5000 inhabitants.

education

In the course of taking over church administration in the 1540s after the introduction of the Reformation, the emerging state was assigned a new field of activity, education , which had previously been the competence of the church. Three Saxon princely schools emerged from secularized monastery property to prepare for the newly founded universities. The school authorities Pforta , Grimma and Meißen were formed, which served to maintain the three state and princely schools. In 1498 the Zwickau Council School Library was founded, the first public academic library in Saxony.

The first area-wide visitation to implement the Reformation in Electoral Saxony took place from 1528 to 1531. As part of these examinations, the sexton and pastor in the parishes also took stock of the lessons . A comprehensive Saxon school plan within the emerging Saxon church ordinance was concluded in 1580 in the Electoral Saxon church and school ordinance . This regulated the establishment of urban Latin schools and rural sexton schoolswhich encouraged both boys and girls to read, write, and sing hymns. As a result, the number of classrooms and school locations increased in Saxony within a few decades. In the 16th century, Saxony's cities had a high density of around 100 schools. Around 1600 there were only a few parishes that did not have their own sextonry. The visitors also encouraged the formation of girls' schools. The provisions of this order remained decisive until the end of the 19th century and ensured that the level of education was raised and previous reforms in church, universities and schools were completed.

For another 300 years the schools that were created in this way were the parishes and cities or private educational institutions. Comprehensive educational institutions for the third class that went beyond the level of simple country schools were lacking in the Electorate of Saxony. An increase in the level of education to the general public with the formation of state educational institutions did not take place until the 19th century at the time of the kingdom. The first two universities in the Electorate were the Leucorea in Wittenberg in 1502 and the University of Leipzig, founded in 1409. In 1764 the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts and the Leipzig Academy of Graphics and Book Art were founded . In 1765 theTechnical University Bergakademie Freiberg founded.

In the first half of the 18th century took place in the course of education , the formation of academies of science in many European countries. In Saxony it didn't exist until 1846, more than a hundred years later.

Health and welfare

A comprehensive, centrally organized health system and social services did not yet exist in the Electorate of Saxony. Since the Middle Ages, caring for the poor and the sick has essentially been a task of church institutions. Benefits for the poor or the sick fell to the family or the guilds for guild members. With the Reformation, caring for the poor also became a communal task. There were three large hospitals in Dresden that were responsible for health care. These were the Maternihospital , the Bartholomäus Hospital and the Jakobshospital . In Leipzig there was the Jacobshospital , the Johannishospital and theHospital St. Georg . In the country there were also poor and elderly care institutions, which were supported by the church but also financed by princely pensions, such as the Hospital of the Holy Spirit in Zahna . Other cities in Saxony also had hospitals, such as the Heilig-Geist-Hospital in Görlitz .

In the reform movement of Pietism , the Moravian Brethren acquired more far-reaching importance. The Protestant Free Churches increasingly came up with a not inconsiderable share for the population in need of care. By developing social entrepreneurship , they were able to generate the funds themselves. The most important pioneer in the field was its founder Nikolaus Graf von Zinzendorf (1700–1760).

The basic level of medical and social services remained generally low in the 18th century and the level of training of health workers was poor. It was not until November 18, 1748 that the Collegium medico-chirurgicum was founded in Saxony as the first medical training center in Dresden, based on the example of other countries.

Culture

The Saxon leaders of the early modern period attached great importance to appropriate consideration of cultural concerns. This basic attitude favored a strong differentiation of society and an increase in the civilizational level of the population. Over time, it is a big city and sophisticated embossed developed educated middle class in several Saxon cities. The functional elites in Saxony at the time formed and led society. By forming international networksthey found connection to the elite of the pioneering societies in the west, took over important innovations from them and implemented them in Saxony. The social structures changed constantly and remained open to cultural innovations. This enabled Saxon society to keep pace with western developments throughout the early modern period and not fall behind.

Promoting civilization

During the Renaissance, a regional form of Renaissance architecture called the Saxon Renaissance developed . The Cranachhöfe in Wittenberg were, at the same time as Albrecht Dürer in Nuremberg, a place of cultural creation that, like the Nuremberg painter, gained national importance. The Saxon court painter Anton Raphael Mengs was a pioneer of classicism and was considered the greatest painter of his time.

Saxony experienced a flourishing of civilization in the 18th century. In Dresden and Leipzig, but also in the smaller official and mansions, very fine manners developed in the Baroque era. This also radiated internationally. Numerous representative buildings in Dresden, but also in the entire state, met the need for representation of the Saxon electors. The Dresden court became known throughout Europe for its opulent court parties. The age went down in history as the Augustan age. The Baroque Dresden was materially from Matthew Daniel Pöppelmann designed, in addition to numerous homes, church buildings as the Epiphany Church , the Zwinger ,Pillnitz Castle (1720) and the Moritzburg Hunting Lodge (1723–33) created. In Dresden a unique ensemble of cultural forms and goods was created, which were brought together in the Dresden State Art Collections .

The regional commitment and the formation of cultural life differed in a high culture formation and a broad culture . Through Johann Sebastian Bach's work, Leipzig became a city of music and thus a place of high Saxon culture, carried and developed by the bourgeoisie. Georg Philipp Telemann directed the Oper am Brühl , the second civil choir in Germany. In the Ore Mountains, significant handicrafts developed in the artistic and creative area, which are more likely to be assigned to the broad culture. The Schwibbogen from the Erzgebirge or the Nutcrackerare such cultural products. Other forms of culture of daily life from this period are the development of certain goods and forms of food in the various regions. The development of the Dresden Christstollen , for example, goes back to a political event, prompted by the Dresdner Butterbrief .

Art collections

Vacuum Pump by Jacob Leupold from 1709 in the Mathematisch-Physikalischer Salon in Dresden

The art collections of the electors were used to accumulate and disseminate technical knowledge . The Kunstkammer , created by Elector August around 1560 , was the second of its kind north of the Alps after Vienna . The collection was designed primarily for technical education. Three quarters of all exhibits were tools. It was possible to borrow tools, instruments and books.

research

The high level of culture in Saxony meant that innovations in technical and social life could arise and that repeatedly gave individual impulses for improvements in all social fields. Porcelain was invented by Johann Friedrich Böttger . The first daily newspaper in the world, Die Einkommenden Zeitung , was published in Leipzig by Timotheus Ritzsch from 1650 , Adam Ries wrote arithmetic books and developed mathematics. Gottfried Silbermann built famous organs in Saxony. The oldest technical university in the world is the Bergakademie in Freiberg, founded in 1765 by the Saxon General Mining Commissioner Friedrich Anton von Heynitz. The homeopathy was 1796 Samuel Hahnemann developed. Also important were the mineralogist Georgius Agricola , who is considered the founder of modern geology and mining, and the philosopher, mathematician and experimenter Ehrenfried Walter von Tschirnhaus , whose work promoted the development of laboratory research methods, materials research, foundries and metallurgy and optical device construction . Other inventors were the mechanic and master craftsman Jacob Leupold , the court mechanic and model master Andreas Gärtner and the hydraulic engineer and chief miner Martin Planer .

Political history

The period from 1180 to 1356 marked the institutionalization process of the Saxon electorate. In addition to the formation of the Courland, the gender classification was also subject to fluctuations and was by no means guaranteed. The written granting of the cure rights from 1356 to the extinction of the Askanians in 1423 formed the next development step towards what the Electorate of Saxony should one day become. With the assumption of the electoral dignity, the Wettins gained connection to the highest imperial politics and thus formed a larger territorial complex, which they held together in the empire until 1806.

Beginning of the institutionalization of the electorate in the early 13th century

From the end of the 12th century to the middle of the 13th century, a narrower circle of special royal voters (electors) had formed, who succeeded in excluding others from being eligible to vote. At the beginning of the institutionalization process, the electoral college consisted of only four princes, two secular and two clerical. The Duke of Saxony was, along with the Count Palatine, one of two secular princes who were allowed to claim the right to vote. This circle was expanded in the 13th century to include the three Rhenish archbishops of Mainz , Trier and Cologne as well as the Count Palatine near Rhine , the Duke of Saxony, the Margrave of Brandenburg and the King of Bohemia .

The allocation of the spa rights to individual territories took place in the early 13th century and was consolidated from then on.

Transformation of the Duchy of Saxony (1180-1260)

The consolidation process of the electoral dignity took place at the same time as the formation of the Saxon duchy. The Duchy of Saxony, which emerged from the Saxon people , has experienced a continuous and multiple transformation process since the end of the 12th century. The Saxon ducal dignity remained, but the territory that defined the Duchy of Saxony was constantly changing and only found temporary stabilization with the formation of the Duchy of Saxony-Wittenberg after around one hundred years. This territory no longer has any cover with the eponymous predecessor, both population-based and territorial.

The actual tribal duchy of Saxony (also known as the Old Saxony) roughly corresponded to today's territory of Lower Saxony . But in 1180 the powerful Saxon prince, Duke Heinrich the Lion, was ousted and his duchy was divided: the western part of the country was subordinated to the Archbishop of Cologne as the Duchy of Westphalia . The Ascanians were enfeoffed with the eastern part of the country, which continued to be called Saxony . Bernhard III.became the first Saxon duke. However, this did not succeed in building extensive territorial rule over the area of the old Duchy of Saxony assigned to him, so that the new Ascanian Duchy of Saxony was only formed by the title and some imperial fiefs (Lauenburg, Wittenberg). As Duke of Saxony, Bernhard III belonged. one of the most distinguished princes of the empire and in this dignity he was one of the most important royal electors in 1198 and 1208.

He was followed by Albrecht I. After his death in 1260, his sons Johann I and Albrecht II divided his land according to the principles of the Ascan family, which only introduced primogeniture in 1727 . The Duchy of Saxony was then divided into the Duchies of Saxony-Wittenberg and Saxony-Lauenburg. Initially, both brothers ruled together, but after the acquisition of the Burggrafschaft Magdeburg in 1269, it was finally divided into two duchies of Saxony-Lauenburg under the rule of Johann I and Saxony-Wittenbergproven under the reign of Albrecht II. The separation was formalized in 1296. The latter duchy succeeded in permanently claiming the electoral dignity for itself. As a result of these divisions, the name Saxony crossed the old cultural border of the Elbe-Saale line in the course of the historical change of name .

Saxony-Wittenberg becomes Electoral Saxony (1260–1423)

|

Saxony-Wittenberg line (dukes and from 1355 electors of Saxony) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Albrecht II. | 1260-1298 | Son of Albrecht I. |

| Rudolf I. | 1298-1356 | Son of the predecessor |

| Rudolf II. | 1356-1370 | Son of the predecessor |

| Wenceslaus I. | 1370-1388 | Brother of the predecessor |

| Rudolf III. | 1388-1419 | Son of the predecessor |

| Albrecht III. | 1419-1422 | Brother of the predecessor |

The Wittenberg Ascanians Albrecht I , Albrecht II and Rudolf I ruled for a very long time as dukes of Saxony, secured the continuation of the dynasty with several sons and asserted themselves as heirs to the Saxon electorate. The electors mainly took care of external conflicts with other territorial rulers and promoted the development of the still sparsely populated area. In 1290 this duchy was expanded to include the Burggrafschaft Magdeburg and the Grafschaft Brehna . There was still further area expansion. The Duchy of Wittenberg in association with the County of Brehna formed Saxony-Wittenberg . This was roughly the same as todayDistrict of Wittenberg , the district of Elbe-Elster , Bad Belzig and Wiesenburg / Mark .

The electoral dignity was not institutionally regulated until 1356. Customary law had reached a quasi-legal status, which was additionally documented in the Golden Bull . As a result, Rudolf I, as Duke of Saxony-Wittenberg, was granted permanent electoral dignity by Emperor Charles IV . The indivisibility of the territory was also established. As a result, Saxony-Wittenberg secured the previously exercised right to elect a king and many other privileges, which made the dukes rise to the rank of the highest-ranking princes in the empire. The duchy on the middle Elbe and the city of Wittenbergthus experienced a gain in importance, because Saxony-Wittenberg had finally risen to one of the seven German electoral principalities. In terms of size, however, it remained a rather insignificant territory in the empire. The area was around 4500 to 5000 km². There were no major urban centers. The strategic location along the middle course of the Elbe made the area interesting.

The Saxon electors also held the office of Arch Marshal of the Holy Roman Empire.

The Ascanians of Sachsen-Lauenburg then finally lost all claimed rights of claim of the vote, which were transferred to Sachsen-Wittenberg alone. This also included the right to carry a sword in the Reichstag .

Renewal of the electorate

The Ascanian house of Saxony-Wittenberg was hit by an astonishing number of accidents after 1400. In November 1422 Albrecht III died. , Elector and Duke of Saxony-Wittenberg from the Ascanian family, without descendants entitled to inheritance.

The German king withdrew the duchy as a completed imperial fief. This happened on the basis of the provisions of the Golden Bull of 1356. After that, when a Kurhaus became extinct, the land was to be reassigned by the king with the voting vote. Saxony-Wittenberg had little power, but as an electorate it was endowed with a high rank. Therefore, the replacement of the Saxony-Wittenberg area was also in great demand.

As a result, both the Lauenburg Ascanians under Duke Erich V and the Meissnian Wettins in the person of Friedrich I. claimed Saxony-Wittenberg and the electoral dignity associated with it. As part of the German medieval eastern settlements east of the Saale and Elbe, the Wettins had come to larger territorial complexes in their margravial positions, which bordered on the south and east of Saxony-Wittenberg.

Frederick I's claim was based on his involvement in imperial affairs in the fight against the Bohemian Hussites . In 1423 King Sigismund announced the political legacy of Albrecht III. as a completed imperial fiefto the Wettin margraves of Meißen and granted them the electorate of Saxony, with which the electoral dignity passed to them. As a result, the Margraviate of Meissen became part of the Electorate of Saxony and lost its status as an independent principality. The transition took place with the further binding of the electoral dignity to Wittenberg. This means that whoever owned Wittenberg also held the title of elector and the electoral vote of the arch marshal. Electoral Saxony remained limited to the area of Saxony-Wittenberg. The former duchy was incorporated as a spa district into the dominion of the Wettins and was able to maintain a quasi-dominant position in the state of Wettin until 1548.

The Wettins, expanding their holdings of Landsberg and Brehna , had already been Margraves of Lusatia in 1089 and Margraves of Meißen in 1125 and were now able to gain a strategically important area in the north of their territories with Saxony-Wittenberg. This enabled them to have traffic connections to important northern German cities such as Magdeburg and a stronger integration into the central Elbeland up to the Harz foreland , which at that time was already densely populated and provided important economic impetus. Access to the Elbe made it possible to participate in trading activities with the Hanseatic Leaguewhich had incorporated several cities along the river into the network. The former colonial land between Saale and Elbe found connection to the old settlements in the west through this empire-political upgrading, almost at the same time as the re- electoral state of Brandenburg by the Hohenzollern . From then on, the Wettins rose to become a hegemonic power in Central Germany. Politically, the Wettins proved to be committed administrators of the empire in the future and formed a coherent territorial complex, primarily through purchases in the 15th century.

The name "Saxony" gradually migrated from the area around Wittenberg, which later became the Kurkreis, to all Wettin areas on the upper Elbe.

Among the Wettins from 1423

The political development in the Electorate of Saxony was influenced by three events between 1423 and 1485: the Altenburg partition , the Saxon fratricidal war and the Altenburg prince robbery . In the newly created Electorate of Saxony, the aristocracy, clergy and cities developed and distinguished themselves into influential classes that took a growing part in politics and administration. From 1485 Saxony was again separated into an Ernestine and an Albertine part of the country.

Formation of the territorial complex in the late Middle Ages

Ruling Electors:

|

On January 6, 1423, the Meissnian Margrave Frederick IV. Was provisionally and on August 1, 1425 formally enfeoffed in Budapest by the later Emperor Sigismund with the Duchy of Saxony-Wittenberg ; as Friedrich I he was now Duke and Elector of the Empire . He prevailed against several competitors. A trial by Duke Erich V of Sachsen-Lauenburg against this decision at the Council of Basel was unsuccessful.

Around 1430, during the Hussite Wars, the Hussites invaded Saxony, which led to the destruction of cities. Elector Friedrich II had already concluded a separate peace with them on August 23, 1432 for two years, but it was not until 1436 that the acts of war ended everywhere. The former power center of the Wettins, Meißen with its Albrechtsburg castle , gradually lost its political importance. Since representation and residence also gained in importance in the early phase of the Renaissance , the Wettins created Dresden in the Elbe basina new residence at the end of the 15th century. It became the permanent abode of the elector, his councilors and administrative officials. There was a warmer microclimate there, which made it possible to grow wine , and an attractive environment close to the Elbe Sandstone Mountains.

The elector's increased expenses for equipping and maintaining the army, or for his own court, could no longer be covered by his own rulers alone. The solution was to levy new types of taxes. However, this also required the approval of the stands. The meeting of the estates organized under Friedrich II in 1438 is considered the first state parliament in Saxony . The estates of Saxony were given the right to come together for innovations in taxation even without being convened by the ruler. As a result, parliaments took place more and more frequently and formed the Wettin corporate state, which existed until the 19th century.

As is customary in other German houses, the Wettins regularly divided their possessions among sons and brothers, which often led to tensions within the family. After the death of Frederick IV. Landgrave of Thuringia, in 1440, came on a wettinischen escheat the land county Thuringia back to the electorate. Disagreements between his nephews, Elector Friedrich II. And Wilhelm III. initially led to the division of Altenburg . In the Altenburg division in 1445, Wilhelm III. the Thuringian and Franconian part, Friedrich the eastern part of the electorate. The mines remained common property.

Despite the power of Halle in 1445, the conflict escalated because Friedrich chose Thuringia in Leipzig on September 26, 1445 and not Meissen. Then the Saxon fratricidal war broke outout. After five years of war, the same state as in 1446 was finally achieved, but large parts of the country were devastated. The war finally ended with the Peace of Pforta on January 27, 1451. The treaty confirmed the division of Altenburg, which temporarily divided the Wettin sphere of influence into an eastern and a western part. The western part of Saxony, which had been ruled by a branch line of the Wettins since 1382, fell after the death of its last representative, Duke Wilhelm III. of Saxony, back to the Wettin main line in 1482, restoring the unity of the country. As a result of the war, the prince robbery Ernst and Albrechts zu Altenburg occurred in 1455 .

The agreement reached in 1459 between Elector Friedrich II and Georg von Podiebrad , King of Bohemia, in the Eger main settlement , which resulted in an inheritance and a clear demarcation between the Kingdom of Bohemia and Saxony, was of great importance for the development of the country .

Beginning of the joint rule of Ernst and Albrecht

| Ruling Electors: |

When Elector Friedrich II died in Leipzig on September 7, 1464, the eldest son Ernst took over at the age of 23. This began an almost twenty-year period of joint government with Duke Albrecht . Both ruled in unison at first, favored by a long-lasting economic upswing that began and increasing urban development in the country. The agreement of all political actions and decisions was secured by holding the two families together in the Dresden Palace. From 1471 both had a new French-style castle built on the Burgberg in Meißen. In their policy, the brothers pursued a further settlement with Bohemia and provided the empire with active military aid against the Ottoman Empireand against Burgundy .

During the time of the joint rule of Ernst and Albrecht, extensive silver finds were found in the Ore Mountains , which stimulated a sustainable economic upswing with the so-called Second Big Mountain Scream. Since the 1470s, the focus of silver mining has shifted from Freiberg to the central and western Ore Mountains. The lavish princely dividends from mining enabled the Saxon princes to have a broad domestic and foreign policy agenda. The existing financial strength was reinvested in the purchase of dominions within the Wettin dominion and in the expansion of the territory to the north and east.

Leipzig became an important economic center of the Holy Roman Empire after the emperor gave it the right to hold annual fairs three times a year . At these imperial fairs , the electors were able to convert the silver finds into cash, thus had full household coffers and began a brisk construction activity. Due to the imperial granted market and stacking rights of the city of Leipzig , the traffic frequency on the Via Regia Lusatiae Superioris , the most important traffic route between Western and Eastern Europe, which crossed the Via Imperii in Leipzig . Leipzig thus became a major continental trading center for all of Europe. From theFree imperial city of Nuremberg , which was an important economic center in Europe at that time, more than 90 merchants and their families moved to Leipzig between 1470 and 1650. The trading network expanded as a result and encompassed all of Europe, dealers from all over Europe from then on offered their goods in Leipzig. Leipzig became a hub for all parts of Europe. The customs revenue along the route benefited the electoral treasury. In 1480 the printer Konrad Kachelofen from Nuremberg settled in Leipzig and established the Leipzig tradition of printing with his printing press.

The state organization was expanded based on the state order of 1384. The state order of 1482 regulated the maintenance of the peace, the legal and social conditions in the state and partially standardized public life. In 1483 the Elector Ernst and his brother Duke Albrecht set up a court with a permanent seat in Leipzig as the Oberhofgericht . It was occupied by nobles and commoners. It was the first independent authority in Electoral Saxony, detached from the prince and court. An effective local and central administration secured the rule of the electors. Internal security was also restored after robber baronism in Germany had led to unrest and insecurity. The feudwas removed, the streets secured against robbery and an efficient legal system established. Compared to the other German states, Saxony became a state that was culturally, economically and state-advanced at that time.

The western part of Saxony, which had been ruled by a branch line of the Wettins since 1382, fell after the death of its last representative, Duke Wilhelm III. of Saxony , in 1482 back to the Wettin main line under Elector Ernst . In his hands there was now a territorial complex that was also important on a European scale. This made Saxony next to HabsburgSphere of power to the second power in the Holy Roman Empire. The Wettiner family network had expanded. There were Wettin family members as clerical dignitaries from Magdeburg, Halberstadt and Mainz. Other entitlements existed for the Lower Rhine duchies of Jülich and Berg, Quedlinburg and Erfurt. The dynastic inheritance and family policy indicated further expansion efforts. However, this favorable family position could not be maintained.

Renewed division of the country

The tensions, which had their origin in the family relationships, increased between the two brothers and escalated from 1480 when Albrecht gave up the common court and moved with his family and his court to Torgau in the Hartenfels Castle. On August 26, 1485, the two Wettins in Leipzig agreed to divide their property, which was carried out on November 11, 1485. As a younger Albrecht could choose his own part of the country, while Ernst determined the division. It went down in the history of Saxony as the main division of Leipziga. The majority of the territories were now governed separately. The division of Leipzig, which was not originally intended to be permanent, weakened the previously very powerful position of the Electorate of Saxony in the Holy Roman Empire. The amicable relationship between Albert and Ernst, which ensured a close connection between the two parts of the country, turned into an open confrontation between the two ruling houses after a few decades.

| Ernestiner - Electorate of Saxony | Albertiner - Duchy of Saxony (1485–1547) |

|---|---|

|

With his residence in Torgau, Ernst had the focus in the north and had the prestigious spa district in the north. Its controlled territory consisted of 14 other exclaves in addition to the main complex . The Ernestines retained the title of elector, which could be transferred to all male members of the family. In the Ernestine Electorate, Frederick the Wise founded the University of Wittenberg , which was the starting point for the ecclesiastical Reformation . In 1505, Elector Friedrich called the painter Lucas Cranach the Elder to his court in Wittenberg. He worked in Wittenberg for decades and created lasting works that carried the Reformation period from Wittenberg into the world. Elector Friedrich expanded the district of Kursachsen as a territory and expanded the castles in Torgau and Wittenberg, among others, into representative residences. From the posting of the theses in Wittenberg in 1517 to the end of the Schmalkaldic War, the Kurkreis and the Ernestine possessions of Saxony were the focus of world public opinion, as the first phase of the Reformation was anchored here, which spread worldwide. The Ernestine Elector Friedrich the Wise (1486–1525) protected Martin Luther . As a result, however, the Ernestines also came into conflict with their Albertine cousins, who initially remained loyal to the imperial-Catholic side in the erupting religious wars. The Ernestine side was committed to the Reformation across the empire, with the Schmalkaldic League they formed a counterweight to the imperial-Catholic side and openly challenged them. |

Albrecht resided as Duke of Saxony in Dresden and had the focus in the east. He had the strategically better territorial complex because it consisted of only two main territories and had four other exclaves. The two largest Saxon cities Leipzig and Dresden were in this ruling complex.

Financial development:

In the Albertine camp, Dresden was expanded as a residence . The Saxon renaissance , which was pushed on by the princely side , was also shaped in the Albertine part of the country. The Albertine Duke George the Bearded (1500–1539) fought Martin Luther and refused to take open action against the emperor. Only after George's death was the Reformation introduced in the Albertine part of the country. |

The events of the Peasants' War of 1525 only touched Saxon territories at the edge of the Vogtland and the Ore Mountains. The pressure on the peasantry was lower in Saxony than in the south-western regions of the empire. This is explained by the strong sovereign position and administration, which imposed restrictions on arbitrary forms of the wealthy nobility.

Rise of the Albertines to the Protestant protective power in the empire

In the battle of Muhlberg in the Schmalkaldic War of the Albertine Duke Maurice defeated of Saxony (1547-1553) as an ally of Emperor Charles V. his cousin, the Ernestine Elector Johann Friedrich von Sachsen-Wittenberg . After the defeat, the Wittenberg surrender of the Ernestine took place on May 19, 1547 . On June 4, 1547, the Albertine Moritz was enfeoffed by Emperor Charles V in the field camp in front of Wittenberg, at the Augsburg Reichstag on February 24, 1548 the solemn enfeoffment with the Duchy of Saxony-Wittenberg followed.

The Ernestine line lost half of its property and only retained the offices of Weimar , Jena , Saalfeld , Weida , Gotha , Eisenach and Coburg . However, the offices of Dornburg , Camburg and Roßla came in 1547, the offices of Sachsenburg , Altenburg , Herbsleben and Eisenberg through the Naumburg Treaty in 1554 to the Ernestine Saxony. The remaining Ernestine duchyAs a result of inheritance divisions, divided into different lines, the Ernestine duchies . In 1572 the continual fragmentation of the Ernestine possessions into numerous small states began. Two main Ernestine lines emerged in 1640: The House of Saxe-Weimar and the House of Saxe-Gotha . While the former had only a few branch lines, which were eventually united to form Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, the House of Saxe-Gotha had a large number of branch lines that mostly ruled over their own country. The last three of these duchies, like Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach, became part of the Free State of Thuringia after 1918 .

The Albertine territories largely became the traditional bearers of today's Saxony. Saxony once again became the second most important German state in the Holy Roman Empire after the Habsburg states, with the ability to have a decisive say in imperial politics. Electoral Saxony now formed a closed Upper Saxon-Thuringian territorial state along the middle course of the Elbe , which, however, did not have a closed territorial structure. Elector Moritz and his successor, his brother August, were anxious to fill in the gaps . The cities and councils that were acquired from Dresden for the Albertine line paid homage to the new Prince Moritz. Melchior von Ossa took part in the Kurkreisthe homage to the new Elector Moritz. On July 13, 1547, a state parliament was convened in Leipzig for two weeks, in which the estates of the old and new territorial area, counts and lords , knights and cities came together and formed a state representative .

Contrary to the emperor's promises, Moritz did not receive all of the Ernestine territories. Moritz succeeded in clearing the way for the recognition of the new faith in the empire. "Since then, the Electorate of Saxony has been the most important protective power of the Protestant faith in the stately and denominationally fragmented German Empire." On July 9, 1553, the Elector, who was only 32 years old, died of the consequences of a war injury sustained in the battle of Sievershausen . After the conclusion of the Augsburg Religious Peace in 1555, Saxony was firmly on the Habsburg side. Elector August saw himself as the leader of the Lutheran imperial estates , in whose interests the status quo achieved between Protestants and Catholics was to be preserved.

After an attack on the diocese of Würzburg by Wilhelm von Grumbach on his own behalf, the latter fled via Lorraine to Weimar and found refuge with the Ernestine Duke Johann Friedrich the Middle, with whom he allied. The duke continued to claim the electoral dignity that had been revoked from his father. On the Imperial Deputation Day in Worms in 1565, Emperor Ferdinand I entrusted the Saxon elector with the enforcement of the imperial ban on Grumbach. After the imperial ban against the Ernestine Duke was pronounced in 1566, Elector August began military action. At the head of an army of 5,489 riders and 31 FähnleinHe began the siege of Gotha on December 24th, 1566 . The city capitulated on April 13, 1567. Duke Johann Friedrich the Middle surrendered to his Albertine relative. The successful execution of the Reichsacht strengthened Electoral Saxony's position in the Reich. After the Grumbach feud , the Albertine electoral dignity and the Naumburg Treaty were never again questioned by the Ernestines.

Land expansion

Ruling Electors:

|

Comprehensive administrative reforms followed after the incorporation of the new territories into the Albertine domination, which rearranged the newly created territorial complex. Ludwig Fachs was an important advisor to the elector on these issues . Moritz “divided his territory into five administrative districts. They were each headed by a captain who was responsible for general and military security as well as for the financial affairs in his district. ” From then on, the court councilor formed the central highest administrative authority, followed by the middle instance, the district administration , represented by the chief officers. The lowest state administrative level or agents of the elector formed the offices, represented by theBailiffs . Thus, shortly after the end of the Middle Ages, a functioning body of authorities emerged in Europe, which is comparable to today's administrative structure. In addition to the administration, the judiciary was also reformed and on December 22, 1548, the Court of Justice regulations were issued. In 1550 the court in Wittenberg was restored. Circular letters to the cities and offices asked them to record all incomes and income relationships and send them to the Councilor. That was the beginning of the official inheritance books , a comprehensive nationwide cadastre for orderly financial management. The writing of the exercise of power by Barthel Lauterbach was decisivepromoted. Further specialist authorities have been set up in the areas of church and justice, mining and coinage . In 1547 the new electoral state had two universities ( Leipzig and Wittenberg), each with a law faculty and, in addition to the two court courts, also two lay judges . An effectively functioning territorial state emerged.

In 1559 the Protestant dioceses of Meißen , Merseburg and Naumburg and in 1596 the Vogtland became part of the Electorate of Saxony. This territorial consolidation made it possible for the sovereign to continue expanding the country . The electorate earned 865,000 guilders a year in average state income. This profit came mainly from the mountain shelves and not from coinageearned. The Wettins had the sole silver monopoly. The cash supply was high, but the national debt amounted to 2,400,000 guilders. Administrative reforms and an active economic policy in the second half of the 16th century were successful. According to Michael Richter , Saxony "became the richest German state of the time on the basis of its trade, industry and mining."

After the establishment of the Dresden mint in 1556 for better control, Elector August (1553–1586) ordered the closure of all state mints . In 1586 the first Saxon state survey was carried out under the direction of Matthias Oeder . In 1572, the Electoral Saxon Constitutions followed , which consisted of civil, state, feudal and inheritance law as well as contract law. With this, Elector August created for the first time a compilation of applicable law based on Roman law , after contradicting judgments by various courts had increasingly led to complaints.

Second Reformation

Despite the Augsburg Religious Peace of 1555, the anchoring of the Reformation had to be actively pursued. In the 1560s and 1570s, a movement originating from Zwingli and Calvin to ward off the Counter-Reformation after the Council of Trent in 1564 began to spread across Europe. The Calvinist movement reached Electoral Saxony in the second half of the 1580s. When Elector Christian I took office by taking over the presidency of the Privy Council on January 24, 1581, the attempt to introduce the Second Reformation in Electoral Saxony began. Nikolaus Krell, Hofrat in the Dresden government since 1580, and Andreas Paull , member of the Privy Council, were the co-determining political forces and represented the Reformed party at the Dresden court, which soon prevailed against the Lutheran Orthodox Party. The new church order was implemented nationwide. With the death of Christian I after a serious illness on September 24, 1591, the attempt to introduce a reformed church system in Saxony ended abruptly. Since the successor Christian II was only eight years old, there was a guardianship government under Friedrich Wilhelm von Sachsen-Weimarused from 1591 to 1601. The Calvinist currents were violently fought from then on in Saxony, Calvinist supporters were removed from all offices and the houses of wealthy Calvinists were stormed and set on fire. After the persecution of the Calvinists, especially by Elector August's personal physician Caspar Peucer (1525–1602) and his secret councilor Georg Cracau , the concord formula drawn up in Torgau in 1577 was the last confession of the Lutheran church , which was ultimately included in the concord book, an all-encompassing body of canon law. The visitation was an electoral instrument for the implementation of the Reformation and the order of religious life in Electoral Saxony . To this end, individual visitors traveled to the individual church locations. The first area-wide visitation in Electoral Saxony took place from 1528 to 1531. The theologian Jakob Andreae (1528–1590) was the general organizer. His goals were based in particular on the implementation of the concord formula and the realignment of the management staff as a result of the waves of persecution of 1574.

The growing differences between Reformed and Orthodox Lutheranism reinforced the influence of the Counter-Reformation that was pursued by the emperor again. Electoral Saxony tried to mediate between the parties in the Reich. Nevertheless, in 1608 the Regensburg Reichstag was demolished by the reformed imperial estates and then the forces were further polarized. In 1608 the Union was founded as an alliance of the evangelical imperial estates and in 1609 the amalgamation of the catholic imperial estates to the league followed. During this time of polarization, the Jülich-Klevian succession dispute took place. Electoral Saxony asserted hereditary claims to the area from the emperor and received the contract from him. Despite the electoral enfeoffment with the Lower Rhine territories, Brandenburg and the Elector Palatinate-Neuburg occupied the duchies, which left Saxony empty. On the Elector's Day in Nuremberg in October 1611, the young Elector Johann Georg I, who had headed the affairs of state as Elector since 1611, brought charges in the Jülisch-Clevischen inheritance matter. Since the emperor died in 1612, the imperial vicariate re-entered after 93 years . The Saxon elector exercised it from May 1613 until the election of Matthias as the new emperor at the Electoral Congress in Frankfurt am Main.

Thirty Years' War

Governing Elector:

|

The outbreak of the Bohemian uprising, initiated by the second lintel in Prague , ended the long period of peace. The elector Johann Georg I sided with the emperor in 1618. In doing so, on the advice of his government, he continued the Saxon imperial policy that had been in effect for decades. Its aim was to preserve the status quo achieved in the Augsburg religious peace. In 1618 Dresden was aware that the Bohemian unrest could trigger a nationwide war. Initially, Johann Georg tried to mediate between the Bohemian estates and the emperor together with the Elector of Mainz. After the death of Emperor Matthiasin March 1619 the situation came to a head. When the Bohemian estates deposed their already crowned successor Ferdinand II in the same year and elected Elector Friedrich V of the Palatinate as their king, Johann Georg gave up his wait-and-see attitude and declared himself ready to take part in the war against Bohemia. It was agreed with Ferdinand II that Saxony should recapture the two neighboring Bohemian states of Upper and Lower Lusatia for the emperor. Formally, Johann Georg was commissioned by the Emperor to execute the Reich against the Bohemian rebels.

In September 1620 the Saxon troops marched into the two Lausitzes. The two margravate could be occupied without major resistance. Because the emperor could not reimburse the Saxon elector for the war costs as agreed, he had to give Johann Georg the two Lausitzes as pledge in 1623.

In the period that followed, Saxony's relations with the emperor deteriorated more and more, partly because the imperial troops under Albrecht von Wallenstein hardly respected Saxony's neutrality . Albrecht von Wallenstein led several pillaging troops into Lusatia. Also ruthlessly practiced recatholizationin Silesia and Bohemia displeased the Saxon elector without being able to do anything about it. In 1631 Johann Georg I finally saw himself compelled to join the Swedes in the war against the emperor. The decisive factor for this radical change in Saxon politics was the military situation, because the Swedish king's troops were already on Saxon territory at that time. Electoral Saxony was mainly affected in its western part. The Battle of Breitenfeld took place near Leipzig in 1631 and the Battle of Lützen in the following yearinstead of. Saxony was militarily active on the side of the Protestant countries and during the battles as an ally of the Swedes. Leipzig was besieged several times during the war, its population fell from 17,000 to 14,000, while the other urban centers, especially Dresden / Meißen, were spared. Chemnitz was badly damaged by the war, Freiberg lost its importance. On the other hand, many smaller towns and villages fell victim to massive looting, especially after General Wallenstein had given his Field Marshal Heinrich von Holk a so-called diversion order, with the execution of which primarily the Croatian light cavalrywas commissioned. From August to December 1632 the Croatian horsemen attacked numerous places (including Dippoldiswalde , Stolpen , Hinterhermsdorf , Saupsdorf , Neukirchen , Reichenbach , Oelsnitz , Penig and Gnandstein ), robbed them, mistreated and killed the inhabitants and left a trail of destruction.

In 1635, Saxony made the Peace of Prague with the emperor and, with the traditional recession, finally came into the possession of the Lusatia. This increased the country's area by around 13,000 km² and almost reached its final limits. The devastation of the country by the Thirty Years' War continued, however, because the fighting against the Swedes continued in central Germany for more than ten years. Electoral Saxony withdrew from direct combat operations for the time being with the armistice of Kötzschenbroda in 1645 and finally with the peace of Eilenburg in 1646.

After the Peace of Westphalia was concluded on October 23, 1648, the Swedish troops had reluctantly left Electoral Saxony. The last Swedes left Leipzig only after payment of the fixed contributions of 276,600 Reichstaler on June 30, 1650. Life increasingly normalized after the recruited mercenaries were released.

Early baroque

Ruling Electors:

|

As a result of the war, the Saxon population was weakened primarily indirectly through epidemics and economic losses as a result of the stagnation of trade, but troop movements and war garrisons also caused a not inconsiderable proportion of losses in the urban and village population. According to Karlheinz Blaschke , the population in Saxony is said to have been reduced by around half due to the war. Other authors point out that this cut may very well apply in individual regions, but cannot be applied to the entire population. However, the losses were largely mitigated by religious refugees, of whom around 150,000 came to Saxony from Bohemia and Silesia. After the complete devastation of Magdeburgits importance as a metropolis in the east of the Holy Roman Empire passed on to the up-and-coming Berlin as well as the cities of Leipzig and Dresden in the Electorate of Saxony.

When Johann Georg II succeeded his father in 1656 at the age of 43, Electoral Saxony was still suffering from the economic consequences of the Thirty Years' War. Only in the reign of Johann Georg III. From 1680 the consequences of the war and war damage as well as the social neglect could be overcome. The repopulation of village farms and municipal household chores was the most difficult. A first sign of the upswing was the increasing tax revenue. Mining, metallurgy, craft, trade and transport recovered slowly but steadily. The mining of silver in the Erzgebirge was no longer dominated by iron, tin, cobalt, bismuth, lead, copper and serpentine. New huts and hammers were built. In 1668 theErzgebirge sheet metal company and in 1659 the Saxon blue color works with headquarters in Leipzig. In addition, the first manufactories were founded at the end of the 17th century as a new form of production that was able to meet the increased demand for textile products in particular better and faster than the manual production method. The Saxon estates had regained their influence during the war due to the high demand for money from the princely treasury. In the second half of the 17th century, the electors had to convene the state parliament far more frequently than was the case at the beginning of that century, and in 1661 the estates were even able to enforce their right of self-assembly.

Saxony had the previous peak reached its territorial expansion, mainly through the 1635 of Bohemia devolved Lusatias . Johann Georg I used the peace to regulate the situation in the country. A new regulation related to the division of the country to his four sons in his will of July 20, 1652. He thus defied the paternal order issued by Albrecht in 1499 , which was supposed to prevent an inheritance from being divided. The will of Johann Georg I , opened on October 8, 1656, provided for smaller parts of Electoral Saxony to be bequeathed to his three sons August, Christian and Moritz and then to be given a secondary education in Electoral Saxonyset up as independent duchies. The duchies of Saxony-Zeitz, Saxony-Merseburg and Saxony-Weißenfels emerged, but fell back to Electoral Saxony in 1718, 1738 and 1746 respectively. During this time, the electoral state was economically, financially and politically weakened by the divisions, even if, from a cultural point of view, new centers with palace buildings, cultural institutions and scientific institutions emerged in Weißenfels , Zeitz and Merseburg . The development of the absolutist way of government, which was also growing in course matters, was hampered by the secondary lines striving for independence.

In the European state system of the late 17th century, medium- sized states such as Saxony, as so-called threshold powers, could hope for advancement into the ranks of the great powers between 1648 and 1763 . In terms of foreign policy, Electoral Saxony, like other states, therefore pursued the goal of promoting its own advancement in a state system determined by competitive struggle. In terms of foreign policy, Saxony remained at the side of the Austrian imperial family until the end of the 17th century. With the death of Emperor Ferdinand III. on April 2, 1657, the imperial vicariate entered, which was carried out by Johann Georg II and exercised for more than a year. On the Electoral Dayin Frankfurt am Main he and the Brandenburg elector pushed through the election of the Habsburg Leopold as German king and prevented an election of Louis XIV of France as German king. A few years later, Saxony became involved in the Second Northern War . In 1664, Saxon troops fought against the Turks in Hungary on the side of the Habsburgs in the Turkish War of 1663/1664 . In the same year Saxony became a member of the Rhenish Alliance for a limited period of four years and allowed French advertisements and troop passes in its area. In 1683, Elector Johann Georg III took part. personally with the Saxon Army at theBattle of the Kahlenberg , which ended the second Turkish siege of Vienna and ensured the liberation of Vienna.

Augustan age

Around 1700 the Age of Enlightenment followed , which stimulated intellectual growth in the population across Europe at all levels of society and promoted education and culture as well as trade and economy. The absolutism prevailed on the continent, only England , Holland and some territories Empire withdrew from the centralization trend. Under these conditions, which were very favorable for Saxony and the ruling family, Friedrich August I (the Strong) took over the electorate in 1694. He shaped the epoch in a contemporary way, so that his time in Saxony went down in history as the Augustan age.

The time stands for the heyday of the Saxon state, in which it was able to develop its highest position of power, cultural achievement and economic strength and this radiated throughout Europe.

The era began in 1694 with August the Strong's coronation as Elector of Saxony and ended in 1763 with the Peace of Hubertusburg.

Absolutism and Saxony's glamor

Painting by Samuel Theodor Gericke, to be seen in Caputh Castle

On April 27, 1694, the prince, who had hardly appeared until then, took over the affairs of state of the Electorate of Saxony as Elector Friedrich August I. During his reign, festivals, baroque splendor, art and patronage as well as lavish splendor and opulence shaped the character of this time. The pompous pomp of this time should take into account the growing European political importance. Court life ranged from ballet performances, Italian and French comedy and opera performances, court balls , banquets , and masked ballssuch as a Turkish masquerade in the Turkish Palace, sleigh rides, hunts and water hunts on the Elbe, ladies' parties with “ring races”, a knight's game on horses and shooting festivals , the inauguration of the kennel with a festival of the four elements , sea battles on the waters near Moritzburg Castle , Fireworks, revue-like elevators, Mercury festivals with improvised fairs.

In addition to the court, the hustle and bustle also included the residents of the residence and the surrounding area as spectators or participants. Purveyors to the court and wage laborers benefited from the electoral orders. Saxon society diversified and continued to develop through the development of an upper-class culture. Overall, the courtly baroque festival culture became an integral part of Augustan government policy. The most important events of this period were the first carnival in the reign of August 1695, the festivities on the occasion of his royal coronation in 1697, and the carnival of 1709 in the presence of King Frederick IV of Denmarkin Dresden, the festivals of 1719 on the occasion of the marriage of Prince Elector Friedrich August to Maria Josepha von Habsburg , the festival of 1727 on the occasion of the convalescence of August II, the festival of 1728 on the occasion of the visit of Friedrich Wilhelm I in Prussia and the Zeithainer pleasure camp of 1730. During a year at August's court, 50 to 60 days were firmly planned festive days. The other days at court were used for political work, planning, administration and government. During the first loss-making years of the Great Northern War, the festivities were less. Even during the presence of the Spanish King Charles III. 1703 or Queen Maria Anna of Portugal There were hardly any celebrations in 1708.

The luxurious life at court exceeded the economic capacity of the country and was ultimately financed at the expense of military strength. The financial problems led to the abandonment of important positions in Central Germany. In addition to Kurhannover , the excessive demands of Electoral Saxony favored the rise of Brandenburg-Prussia to become the second major German and Protestant supremacy in the empire. In connection with court life, a system of mistresses, which can be understood as a kind of court office, was also maintained at the Saxon and Polish courts, which is typical of the time. Important mistresses of August were Aurora von Königsmarck and Ursula Katharina von Altenbockum . The most distinguished mistress at the Saxon court was thatCountess Cosel . After the long-standing and influential mistress fell out of favor with August the Strong, she was brought to Stolpen fortress in 1716 .

Economic boom