Berlin book

|

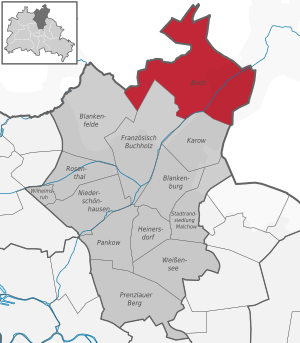

Buch district of Berlin |

|

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 52 ° 38 '11 " N , 13 ° 29' 33" E |

| height | 56.2 m above sea level NN |

| surface | 18.15 km² |

| Residents | 16,868 (Dec. 31, 2019) |

| Population density | 929 inhabitants / km² |

| Incorporation | Oct. 1, 1920 |

| Start-up | 1230 |

| Post Code | 13125 |

| District number | 0309 |

| Administrative district | Pankow |

Buch is the northernmost part of the Pankow district and thus of Berlin . The location on the Panke is characterized by the historic village center, the castle park, extensive hospital facilities and more modern new housing developments.

geography

Book in the Barnim

Buch is located on the Barnim , whose plateau rises quite clearly above the surrounding valleys , in the north and northeast the Eberswalder Urstromtal with the Oder-Havel Canal and the Oderbruch , in the southeast the Buckower Rinne , in the south the Berlin Urstromtal with the Spree as well in the west the Zwischenurstromtal of the Havel . The upper reaches of the Finow and the Panke form the border between the lower western barnim and the higher central barnim.

The northernmost point of Berlin is in Buch . Neighbors, viewed from west to east, are the Brandenburg municipalities of Wandlitz and Panketal in the north and the Pankow districts of Blankenfelde , French Buchholz and Karow in the south.

![]()

structure

The center extends around the Buch train station . This is followed in the east by the historic village center around Alt-Buch. This forms a connection with the largely vacant forest house and with the prefabricated building area Buch III, which continues south of Wiltbergstrasse. In addition, there are loosely grouped around the historical center: the Zepernicker Strasse settlement, Ludwigpark , the Bucher Spitze (municipal headquarters in Buch), the Hufeland clinic campus , the Buch settlement (Siedlungsstrasse) and Buch II. The south-east of the district is taken by the Berlin campus. Book , Book I and IV a. In the east, the Alpenberge settlement (road 4) nestles against the state border. Most of the built-up area is located southeast of the Berlin – Szczecin or Panke railway line . The Buch colony, the Ludwig-Hoffmann-Quartier , the Klinikum-Siedlung (southern part of Röbellweg) and the sand houses are grouped to the northwest. There are two unused hospitals on Hobrechtsfelder Chaussee and the Allées des Châteaux residential park deep in the Buch forest . In the far west there is an industrial park on both sides of the Berliner Ring . The structure of the different quarters is quite diverse. About half of the district is undeveloped.

The development of the area between the Buch Moorlinse and the A 10 is intended to strengthen the central function of the station, but goes against nature conservation .

Surface shape

In the east, an almost continuous, relatively steeply rising ground moraine accompanies the left bank of the Panke . There the Stener Berg marks the highest point at 83 meters. The area west of the ridge shows a lower level of altitude and differences in altitude. A sander fills the majority . The eastern drainage channel of the Wandlitz-Ladeburger Sander joins the Panke-Sander north of Buch. At first like a tube, it narrows in a funnel shape on its way south to the Berlin glacial valley . In the far west lies the Mühlenbeck ground moraine, broken through by the valley of the Fennbuchte. Buch has a small share in both. Overall, the landscape shows a slight east-west waveform and a north-south gradient.

Only at first glance does the Sander appear to be perfectly flat. The lowlands of the Panke and the Lietzengraben and its tributaries have dug into it. The difference in level is sometimes shown by striking edges of the terrain. In addition, a large number of small basins such as the Buch Moorlinse , the Karower Ponds or the Bogensee are deepened in the valleys . To the north and northeast of the latter there are still a few short box valleys . The Panke only flows through a narrow channel. The catchment area of the Lietzengraben, on the other hand, is wider. Its actual valley narrows just before the mouth of the Panke , in the vicinity of the Berliner Ring, to just 50 meters.

Geological history

introduction

The recent history of the earth began 1.8 million years ago with the Quaternary . In Berlin-Brandenburg this system shaped the Quaternary Ice Age, which continues to this day . In the first series of the Quaternary, the Pleistocene , several cold and warm periods alternated. The second series, the Holocene , so far consists of a warm period.

| series | Cold and warm periods |

|---|---|

| Holocene | Holocene Warm Period |

| Pleistocene | Vistula glacial period |

| Eem warm period | |

| Saale ice age | |

| Holstein Warm Period | |

| Elster Cold Age |

During the cold periods, the Fennoscan Ice Sheet expanded from northwest to southeast or retreated in the opposite direction. There were considerable local deviations from this main direction. In addition, the edge of the ice did not form a straight front, but rather resembled a garland. Two different phases occurred during a cold period. During a stadial the ice sheet advanced rapidly, in an interstadial the forward movement was slowed down, stood still or the ice withdrew. Where the glacier stopped there was an ice edge layer . If melting then set in, a glacial series usually formed . Viewed from the ice center, the ground moraine , the terminal moraine , the sander and the glacial valley followed . Therefore, ice edge layers served as the safest method for structuring the cold ages. Deposits of melt water from sand , gravel and / or crushed stone in front of the advancing ice are hot fill, and in front of the thawing ice, refill.

Bucher geological history

The dating of the Quaternary in the Berlin area is in the discussion phase among geologists (status: 2004) and sometimes differs considerably from one another. Therefore, no times are given or should be viewed with caution in this section. The year 2000 serves as the reference point.

The Barnim received its main coinage during the Saale Glaciation . She put u. a. the valleys of Panke and Lietzengraben . During the Eem warm period they flowed through a tree- lined landscape. In the strip from Niederschönhausen - Pankow in the south via Buchholz - Buch in the middle to Ladeburg in the north, drilling took place. The pollen analysis of the drill cores confirmed the Eem forest . The Glaciation of the Vistula used the older forms of the Saale complex, but did not change them significantly.

The Brandenburg phase reached the maximum extent of the last ice age . The edge of the ice roughly described the line Beelitz - Luckenwalde - Baruth - Lübben - Guben . Melt water was already flowing under the thawing inland ice . It was probably already using the drainage lines from Panke and Lietzengraben. When the ice released the Buch landscape around 18,000 years ago, ground moraines and remains of the glacier ice remained in the above-mentioned small basins . These dead ice blocks prevented refilling. The rivers connected small pools in an area almost devoid of vegetation. In their areas, they largely removed the ground moraine from the Vistula period, and the Panke also worked them into a stone base. Both left sand and gravel as refill . The conclusion of the layer package consisting of ice wedges , drifting sands , wind curbs and pollen-bearing still waters - sediments was interpreted as the Karower Interstadial .

At the beginning of the Frankfurt phase, the meltdown paused. The edge of the ice ran on the Barnim from Prenden via Rüdnitz to Tempelfelde , then via Werneuchen to Buckow , with different degrees of severity. After replacing the low-thawing two to five meters of sand and gravel washed over the dead ice, also arose in the subarctic climate , a permafrost . This double protection preserved the glacier remains for around 4,000 years. According to current knowledge, the ice retreated far to the north, perhaps even as far as the southern Baltic Sea region . During the Pomeranian phase , it pushed forward again. The ice edge location in the Joachimsthal - Chorin - Oderberg area later created the Eberswalde glacial valley . Melt water has since played no role in the Buch area.

From the beginning of the Vistula Late Glacial , the permafrost soil slowly dissolved. The loose material above sagged and produced small lakes . In these seasons fine sand and silt were deposited . Meadow lime formed on the flat edge of the basin, e.g. B. in the northern part of the Karower ponds , in the Mittelbruch or in the entire Panke valley. The thawing away of the remains of the glacier also triggered the deep erosion of the Panke and Lietzengraben. The beginning of the valley shifted steadily to the north. Where the permafrost was still present, it prevented lateral erosion, resulting in box valleys with steep valley flanks. The tundra only occasionally interrupted dwarf shrubs . Backfilling of the basins with mud began in the Older Dryas Period . In the Alleröd-Interstadial , mooring and reforestation started with birch and pine trees . The ground moraines and higher areas of the sander mainly influenced wind transport in the late glacial . However, striking dunes only formed outside of Buch.

With the Holocene global warming, today's flora and fauna migrated in stages. Panke and Lietzengraben meandered through valleys with weakly muddy edges. The mostly shallow lakes silted up quickly, until the middle of the 19th century they had become bogs with layers of peat and mudde several meters thick . From the Neolithic Age, humans began to clear the forest for fields, pastures and settlements . During the German East Settlement in the Middle Ages , mill ponds were dammed along the Panke . The resulting rise in the groundwater level caused the moors on the valley edges to grow stronger. The forests, which had become smaller, served as pastures for cattle . In the modern era , drainage systems, fish ponds , river straightening , monotonous pine forests , sewage fields , peat cuttings and more development were added. Despite, sometimes because of human interventions, the Buch landscape holds immense natural value.

Geology and soils

The subsoil is mostly made up of sand , gravel and marl from the ice ages . The sediments of the Elster glaciation are relatively close to the surface in Buch, the main deposits come from the subsequent Saale glaciation . Above this, in sections, there is a Mudde and peat layer from the Eem warm period , e.g. B. developed in the Germanenbad. The Glaciation of the Vistula is not very thick. The till is silted up on the ground moraines . In Sander only 1.5 to 5 meters are provided in place of the evacuated or reclaimed for stone sole moraine to melt water deposits. The peat formation extends into the Holocene .

| Source material | Leitboden | Accompanying floor | use | Danger |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ground moraines with sandy cover layers | Brown earth - pale earth, brown earth | Brown earth gley , brown earth pseudogley , Kolluvisol | Settlements , extensive arable land | Surface sealing , soil erosion from water and wind, partial structural damage from soil compaction |

| Valleys and gullies, partly moors | Brown earth, podsol brown earth, humus gley | Gley, Anmoorgley , low moor soil | Mixed forest , partly alder break , grassland | Peatland degradation when groundwater subsides |

| Former sewage fields | Regosol , Podsol-Braunerde, Kolluvisol , Podsol-Gley | Afforestation , wasteland | Enrichment with pollutants , soil acidification |

The Berliner Rieselfelder left behind a high level of soil enrichment with nutrients and pollutants , particularly due to the improper application of the original concept . The Bucher process developed for ecological remediation was first used in 1998 in the Buch forest .

Waters

The ice edge of the Frankfurt phase during the Vistula glaciation left the Ladeburg-Albertshof threshold zone behind. The terminal moraine in sections represents a main watershed . The northeast side drains to the Oder and thus into the Baltic Sea . The main river of Buch, the Panke rises on the southwest side. This is why it feeds its water to the North Sea via the Spree , Havel and Elbe . Its side stream, the Lietzengraben , emerges not far from the threshold, west of Schönow . The valley of the forest trench also looks back on an Ice Age past. Its water and that of the Seegraben, a junction from the Lietzengraben, unite in the northernmost of the Buch ponds and flow through the entire chain as a ditch 18 and finally merge into the Lietzengraben.

Most of the rivers on the Bucher Sander are of artificial origin and are therefore largely straight and have a barely structured bed . A map from 1876 showed agricultural drainage ditches . When the local Berlin sewage fields were laid in 1898, they were integrated into the network of inflow and drainage ditches for the sewage fields . The legacy of around 80 years of management were u. a. a heavy load of nutrients and pollutants . The main aquifer , from which the drinking water is taken, is well protected against entry . After the irrigation was abandoned in 1985, the groundwater level fell and the surface discharge decreased. Many of the trenches dried up completely, the remaining ones partially dry up in summer. Only Panke, Lietzen- and Seegraben have permanent water. Small weirs and the introduction of purified water from the Schönerlinde sewage treatment plant serve to stabilize the water balance .

The proper names mainly follow a not very prosaic pattern of ditch - number - place, e.g. B. Graben 22 Buch or Graben 132 Lindenhof. The X-Taler digging branches off approximately at the border to neighboring Röntgental on the Waldgraben and drains the mullion . The zigzag ditch was considered the most imaginative , the reason for this choice becomes apparent on site or when looking at a map. The zigzag dance, the spawning ritual of the three-spined stickleback was certainly not the namesake. This and the dwarf stickleback live in almost all sewer trenches. They are adapted to such extreme habitats and find a retreat here .

While in Buch's territory the Panke flows in from the right exclusively the Lietzengraben, twice as many backwaters branch off or join from the left. The canals in the Buch Castle Park were created from 1670 when the Dutch garden was being built and were later changed several times. The Werkgraben already flows into the Schlosskanal in the eastern part of the park. Apparently the work book, a common name for the municipal headquarters book, was named here. The Kappgraben ( Slavic Kopati 'ditch') cuts through the ground moraine and marks the former border with Karow . Its side trenches probably got their names from two institutions from the Weimar Republic , the tree nursery trench from a tree nursery operated by the Pankow Garden Authority and the institute trench from the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Brain Research .

The parts of the Karower Teiche nature reserve along the A 10 belong to Buch, but the ponds themselves belong to Buchholz . The Brende and Buchholzer Graben form the lower part of the Fenn Bay and come from the Mühlenbeck ground moraine. The Lindenhof pond is also on this.

climate

In Buch, the temperate climate that is usual for the Berlin area prevails , which is influenced from the north and west by the Atlantic climate and from the east by the continental climate . Extreme weather such as storms, heavy hail or above-average snowfall are rare.

The mean annual rainfall of 564.3 mm is less than the national average of around 800 mm. Most of the precipitation falls in the summer months of June to August with a peak of 66 mm in June. February has the lowest precipitation with 34 mm. The sun shines an average of 1595 hours per year. The average annual temperature is 8.8 ° C, the average annual relative humidity 78% and the average degree of cloudiness 5.3 ⁄ 8 (66%).

The highest temperature measured in Buch was 38.2 ° C on July 11, 2010, the lowest −24.5 ° C on February 9, 1956. The warmest month of the series of measurements since 1951 was with an average temperature of 23.3 ° C July 2006, the coldest February 1956 with -9.2 ° C. At the third-order climate station (GEMBUS observer), also operated in Berlin-Buch from 1922 and relocated to Bernau-Schönow in October 1933, an even colder monthly mean of −11.0 ° C was recorded in February 1929, with an absolute minimum of −28 , 0 ° C (on February 11, 1929). Most of the precipitation fell with 108.5 l / m² on August 8, 1978. The wettest month was July 2011 with 247.2 l / m². In April 2009, on the other hand, Berlin-Buch was not only the driest station in Germany with just 0.6 l / m², but also recorded the month with the lowest rainfall in the series of measurements. The highest snow cover of 50 cm high was measured on February 16 and 18, 1979. The lowest total monthly sunshine duration occurred in December 1971 and was nine hours; the sun shone the longest in July 1994 with 362 hours.

The uninterrupted regular weather recording began in 1951 with the opening of a research center for bioclimatology on the premises of the Hufeland Hospital . In 1955 it became a research institute, which moved into a new building at Lindenberger Weg 24 in 1961 . The German Weather Service (DWD) - branch of the hydrometeorology department - has been located there since 1990 .

history

The story of Buch can be divided into three phases:

- From the first evidence of settlement in the Mesolithic (8th to 4th millennium B.C.E. ) to the end of the Slavic period ,

- From the founding of the German village (early 13th century), one by the peasants and farmers and basic and landlords dominated era,

- with the emergence of the Berlin-Buch health region (from 1898), embodied by the sanatoriums in Berlin-Buch and the Berlin-Buch campus .

Origin and development of the place name

Martin Pfannschmidt assumed in the history of the Berlin suburbs Buch and Karow that a transfer of the place name from Buch in the Altmark took place. Today the origin is seen in the Slavic language ( Buckow 'Rotbuchenhain' or Buck 'Waldhöhe', also 'beech'). According to the Brandenburg name book , a derivation from Old Polabian ( buk 'beech') was most likely. The Middle Low German word equivalent ( böke 'Buche') was incorporated into this early on .

When it was first mentioned in 1342 as Wendeschen Buk , the name addition Wendisch was used. Likewise in the Landbuch der Mark Brandenburg from 1375, there was in the village register book slavica and in the village register Wentschenbug , Wentzschenbůk and Wentschenbůk . The former referred to older records, the latter partly differed in terms of time and content in the traditional manuscripts , hence the four different spellings in the Landbuch. A loan letter from 1412 named czu windischen Buck ( CDB , main part C, volume I, p. 50, copy), the lap register (fol. 283) from 1450 Wendeschenbuk and that from 1480 Wendisgenbuck . The last time the addition could be found in the Procuration Register of the Diocese of Brandenburg from 1527 to 1529. There was Wendische Marcke or Boeck slauica recorded. In the following years he was missing, so it was called 1570 tzu Bock (CDB, main part A, volume XII, p. 479, original) and 1624 Buck (lap register, fol. 364). At some point the standard German writing style “ book” prevailed. With the formation of Greater Berlin on October 1, 1920, it became Berlin-Buch .

A name transfer took place in the Neu-Buch mentioned in 1927 .

Stone age

At the end of the Vistula Ice Age , the ice sheet gave the Berlin area since the 15th millennium BC. Chr. Free again. A tundra- like landscape emerged on the Barnim , in the area traversed by the lowlands of the Fennbuchte, the Lietzengraben , the Waldgraben and the Panke . Wetlands several hundred meters wide often formed along the water , including some fens . The immigrant large mammals such as reindeer and musk ox followed since the 10th millennium BC. The people of the Younger Paleolithic .

Book one of the archaeologically explored best areas in Berlin with a wealth of ur- and prehistoric finds places. Almost all of them came from the edge of the lowlands from slightly higher and therefore drier sandy soils. So far, no find could be clearly assigned to the Upper Paleolithic. Since the many bodies of water offered the people an ideal habitat, however, settlement must be assumed. The nomads lived in tents or simple huts in order to hunt the game and to be able to collect fruits and roots in larger areas .

In the Mesolithic Age (8th – 4th millennium BC), a dense forest developed in the Brandenburg region due to the Holocene global warming , which displaced the post-glacial flora and fauna. The selection of prey, e.g. B. aurochs , elk , roe deer , red deer , wild boar and bison increased, as did the variety of vegetable food. The hazel bush , which provided nutritious and storable nuts , spread particularly strongly . Fishing also gained in importance. Presumably the people were not yet settled and lived similar to the Upper Palaeolithic.

There are three reliable Mesolithic sites for Buch. In 1935 were to the bird ponds more devices flint excavated, including haircuts , blades , arrow and other tips in the form of microliths . The second site on the west bank of the Lietzengraben also brought microliths to light, but a more interesting core ax made of flint was only about 6.9 centimeters long . In 2007, the third site from the final phase of the Mesolithic on a former field south of the street Am Sandhaus was examined. In the lower part of an oval, about 70 cm × 40 cm large, light brown-beige pit was an extremely well-preserved, polished cylinder ax made of rock . Despite the lack of human bones, organic material decomposes very quickly in the local soil, the find and size of the pit indicated a stool or partial burial . Several flint blades and flakes also suggested a temporary settlement nearby.

From the Neolithic Age , in the Berlin area around 3000–1800 BC. BC, settled farmers settled in Buch . The changed way of life was expressed in stable houses. The technological innovations of the era were called u. a. Clay pot , flint grinding , spinning and weaving of wool , plow , attrition and sickle . In addition to a stone ax made of rock, several flint stones were recovered from two Neolithic sites . Some of the latter were ground on the broad side and had slightly rounded edges. A particularly splendid ax about 17 centimeters long from the edge of the fen bay was attributed to the Middle Neolithic (about 2600–2200 BC) spherical amphora culture.

Bronze age

In the Bronze Age , in the Berlin area around 1800–700 BC. BC, the population in Buch increased significantly. Of the 18 known sites of this epoch, 11 were from the Young Bronze Age (1200–700 BC). Furthermore, the people preferred the slopes of the lowlands , but they also settled down several 100 meters from the waters. One of the Young Bronze Age settlements was on Wiltbergstrasse . It was discovered during the construction of the IV Municipal Asylum . Their extensive excavation in the years 1910–1914 made archeology history. For the first time in Germany, Albert Kiekebusch from the Märkisches Museum was able to reliably record house layouts from the Bronze Age and show the expansion and structure of a village. The methods and techniques for sandy soils he developed during the excavations set the standard for the next few decades.

Without reaching the settlement boundary, over 100 house plots were found, of which were between 1200 and 800 BC during the several settlement levels. BC probably only 10 inhabited at the same time. In addition to the usual, ground-level, small post structures (20–30 square meters, 5.5–7.0 meters long, walls made of wattle smeared with clay), there were also some buildings in block construction . The finds included u. a. Clay plate with twisted rim. These Köpenick plates were typical of the Berlin area. The recovered stone axes were considered to be an indication of a shortage of copper and tin at the end of the Bronze Age. The two raw materials for bronze production became so expensive that the common people had to fall back on the local raw material stone. The urn - burial ground in Alt-Buch 74, which existed at the same time and was examined during the work for the home for breast patients in 1904 and 1912/1913, presumably served the Altbuchers from Wiltbergstrasse as the cemetery . Another Bronze Age village stood in the southwest corner of Buch, on the Dählingsberg .

East of Karower Chaussee , construction workers discovered a bronze hoard in 1984 and illegally divided it among themselves. It was not until 1988 that the state preservation authorities became aware of the finds, which had now been scattered, so their exact scope remained unknown. Some of the pieces could be secured. Michael Hofmann arranged the three swords of the Mörigen type (two completely preserved), the kidney knob sword, the handle of an antenna sword and the broken lance point in the 9th / 8th. Century BC A, Adriaan von Müller reckoned it to the 10./9. Century BC Chr. To. The ornament in the pommel of one of the swords was already made of iron . Presumably the residents of the nearby settlement west of Karower Chaussee made the weapons and buried them as an offering . The Young Bronze Age village on the northern edge of the valley of the Kappgraben built a bridge to the following epochs with its Iron and Slavic Age settlement .

Iron age

The Iron Age began in the Berlin area around 700 BC. BC, around 100 years later than in southern Germany . The early section up to the beginning of the era is known as the pre-Roman iron age . For this epoch, historiography listed the Germanic tribes for the first time as a local national name. Because of a deterioration in the climate , in the 7./6. Century BC BC probably a large part of the population. The settlement west of Karower Chaussee was one of the only four sites, all in the Panke area .

The above has already been examined best. Terrain south of Am Sandhaus . The there in 2006 detected byre-dwelling (about 21 m long and 5 m wide, by partition in 5 m x 5 m large living area and 16 m × 5 m large stable subdivided, alignment in the east-west direction) by means of radiocarbon to the time between 521 and 407 BC Dated. Its classification in the 5th century BC Chr. Closed a chronological gap in the Berlin-Brandenburg house research. A square nine- post granary uncovered in 2007 could also be sorted into the Pre-Roman Iron Age using the same method. Previously, this type of house was only known from the following section.

The late Iron Age between year 1 and the end of the 4th century is called the Roman Empire . The written sources located the Germanic tribes of the Semnones and Burgundies in the Berlin area . The population increased again, the eight known sites were v. a. at Panke, Wald- and Lietzengraben . The systematic recording of the Am Sandhaus area enabled detailed knowledge of the local structure, house construction, economy and material culture of a Germanic settlement of the 2nd / 3rd centuries. Century.

There were three phases of settlement between around 150 and 300. Rivers and swamps offered natural protection in the north, east and west, and to the south there was presumably open terrain up to the Panke, 700 to 800 meters away. The main and residential buildings of a homestead each formed a single-storey long house , surrounded by numerous small buildings. Most of the long structures had two naves and were of different sizes (10.2–20.0 meters long, 3.0–6.0 meters wide) and floor plans, including a trapezoidal one . Nine out of a total of ten recorded longhouses had no subdivision. The subdivision (living area, hall and stable) of the one, its dimensions (four aisles, 37.0 m × 5.0-5.5 m) and the larger number of outbuildings spoke in favor of a socially privileged family. The 31 small buildings discovered in the village varied in size and structure. They served u. a. as work huts, storehouses and stables. In 2005, a paved entrance to a mine house was detected for the first time .

Slaughterhouse waste showed the keeping of geese , horses , cattle , sheep , pigs and goats as well as the hunting of hares , red deer and wild boars . The most important animal food was beef. No statements could be made about the extent and diversity of arable farming , since, as already mentioned, plant remains in the Buch soil rot quickly and a pollen analysis is not available (as of October 2009). The discovery of the bottom stone from a hand rotary mill and several runner stones from attrition mills indirectly proved the grain processing.

In addition to working as arable farmers, cattle breeders and hunters, the people of Buch worked in numerous craft professions: pottery , spinning and weaving of wool , processing of bronze and the production of charcoal , pitch and tar . The production of quicklime occupied five lime kilns . Meadow lime mined near the surface in the wetlands was usually processed in it. However, the raw material for a furnace discovered in 2005 and the clods of the neighboring storage pit were demonstrably Rüdersdorfer limestone , the start of mining was previously dated to the German Middle Ages . Turf iron ore extracted in the area left slag as a waste product when it was smelted in racing furnaces . Their investigation showed that lime was added to improve the process. The iron was probably also processed on site.

Migration and Slav period

At the beginning of the migration of peoples in the 4th century, most of the Germanic tribes left the Berlin area towards the Rhine and Danube . For the 5th / 6th In the 19th century, therefore, no settlement could be proven for Buch. With the immigration of the Slavs in the 7th century from today's Poland and the Czech Republic , the population increased again. The Western Slavs formed two tribal lords in the 8th or 9th century: the Heveller with their headquarters in Burg Spandau and the Sprewanen with their center in Burg Köpenick . Buch probably belonged to the Köpenick reign . Two nearby sites on the left bank of the Panke document the presence of Elbe Slavs between the 9th and 12th centuries . The settlement west of Karower Chaussee examined in 1982 was dated to the 11th and 12th centuries. The fireplaces, storage and waste pits contained ceramic remains and bones from cattle , sheep , pigs , goats and red deer .

Beginnings of the German village

Johann I and Otto III. ruled the Mark Brandenburg together . The two Ascanians expanded it from 1220 a. a. around the Barnim and the Teltow . From this time on, both areas were systematically developed as part of the German East Settlement . Their population increased from about 5,000-10,000 in 1150 to about 35,000-40,000 in 1250.

Book originated in the early 13th century. There is much to suggest that the ancestral Elbe Slavic inhabitants and the German immigrants together formed a village community. According to the settlement geographer Anneliese Krenzlin , it happened several times that in addition to the newly formed German, the older Slavic settlement continued to be inhabited for a while. If this was also the case here, the turning pieces mentioned in 1375 were the left-back farmland of the Slavs. The creation time of book fell into the classic phase of large bathtub . Their length made it possible to use the soil turning plow efficiently and were optimally adapted to three-field farming . The most modern and profitable form of agriculture at the time led to an enormous increase in economic power. Under the guidance of the locator , the farmers measure the land. The Roden of trees and removal of roots came first on the three Zelgen . The number of stripes in each loft originally corresponded to the number of hooves . Then the first tent was immediately ordered. Flurzwang prevailed , which means that each field was used alternately as a summer field, winter field or fallow field. In addition to the field strips, the property included a share in the common land and the farm .

The buildings were not erected until the seeds had been sown, which was essential for survival, here in the form of a street or street perch village . Along the village street (now about Old book and subsequent part of the Walter-Friedrich-Strasse ) is lined up, the farms of full peasants and Kossäten . The latter were not involved in the hoof land and only owned some garden land. On the north side, almost exactly in the center of the village, was the Buch village church and behind it, a little off the village street, the Buch Ritterhof. A watermill rattled on the Panke , the brook was dammed up into a mill pond. That is why the southern part of today's Pölnitzweg was called Mühlenweg for centuries. At its confluence with Dorfstrasse, the forge was perhaps already back then (first mentioned in 1624), and a jug could also have existed right from the start.

Buch was first mentioned in a document in the middle of the 14th century ( BLHA . Pr.Br.Rep.08, City of Prenzlau, certificate 56 or 5b):

"Given on December 13, 1342

Markwart von Lauterbach, margrave of Brandenburg Vogt of the Vogtei Spandau, documents that before him the squire Arndt von Bredow, his wife Anna and their two mature sons Otto and Hans the Jew Meyer zu Berlin and his heirs 16 pounds of Brandenburg pfennigs from the Bede of the village of Gratze and pledged 9 pounds from the bede of the village of Wendeschen Buk against a capital of 125 pounds for a period of 5 years.

The interest payment is to be made for Gratze at Martini and for Buch at Michaelis and Nicolaus. The miners Andreas [von] Sparr and Hans von Bredow are named as guarantors and trustees City of Berlin, if the deposit is refused, the respective Vogt zu Spandau Meyer should be obliged to help with the seizure in the amount of his claim. "

The lending business fell in the time of the Wittelsbach in the Mark. In the case of large payments, the coins were not counted individually, but weighed. 1 pound ( talentum ) was equivalent to 240 Brandenburg pfennigs ( denarii ). A single pfennig minted in Prenzlau between 1334 and 1347 had a fine weight of 0.61 grams of silver . In total, the von Bredow family borrowed 18.3 kilograms of the precious metal (125 pounds × 240 pfennigs / pound × 0.00061 kg of fine silver / pfennig = 18.3 kg of fine silver). Sewing a pair of trousers 1, a male, for comparison, in the year 1346 cost rocks 4 and a woman Rocks 6 Pfennig. In return, the tailor got 2 to 4 loaves of bread or 1 large beer for 1 pfennig. Gratze was and is a village 21 kilometers northeast.

The Landbuch der Mark Brandenburg from 1375 gave more precise information for the first time:

“Wentzschenbůk sunt 40 mansi, quorum plebanus has 4; Smetstorp has 4 mansos ad curiam, tenetur ad servicium. Ad pactum solvit quilibet mansus 7 modius siliginis, 2 ordei et 7 modius avene; ad censum quilibet 2 solidos; ad precariam solvit quilibet mansus quinque solidos den. et 1 ⁄ 2 modium siliginis, 1 ⁄ 2 ordei et 1 avene.

Tabernator dat 10 solidos ad pactum et censum, item ad precariam sicut unus mansus. Molendinum solvit 1 chorum siliginis dictis de Ro̊bel, ultra hoc solvit dictis de Bredow 1 modium siliginis, 1 ordei et 2 modios avene et 10 solidos den. Item ager, qui dicitur Wendestucke, solvit prefecto et dictis de Bredow tantum quantum unus mansus.

Cossati sunt 22, quilibet solvit 1 solidum den. et 1 pullum. Hans et Tamme dicti de Robel have pactum super 10 mansos et 14 solidos ad censum. Smetstorpp has 3 frusta et 8 modios in pacto et censu; Wichusen have 22 modes in pacto; Albertus Rathenow, civis in Berlin, 18 modios in pacto. Item 2 chori et 1 us modius spectant ad altare in Berlin. Fritze and Claus Bredow have frusta in pacto et censu 6. Schultetus habet pactum super 6 mansos et solvit annuatim dictis de Bredow 1 1 ⁄ 2 frustum pro pheudo et 1 ⁄ 2 frustum pro equo pheudali.

Precariam, supremum iudicium et servicium curruum habent dicti de Bredow, habuerunt ultra 30 annos, emerunt a Betkino Wiltberg, milite. "

Wendisch Buch contained 40 hooves , of which the pastor and Schmetstorp each had 4 free hooves. Schmetstorp was required to be a tenant for his knight 's farm . The full farmers had to pay feudal taxes for their land . For each hoof, 2 bushels of barley were to be paid for rent , 7 bushels of rye and oats each, 2 shillings for interest , 5 shillings for Bede , 0.5 bushels of rye and oats each. The same price had to be paid for the turning pieces as for a hoof. The vassal services of the mayor had been replaced by cash benefits. He paid 1.5 counts for the fief , instead of 0.5 counts for the feudal horse. Each of the 22 kossas paid 1 shilling, 1 chicken. The Kruger paid ten shillings for rent and interest, the same for Bede as for 1 hoof. The mill paid to the Röbels of 1 Wispel rye, the Bredows of one shilling, one bushel of oats, 1 bushel of rye and barley.

The rent of 10 Hufen flowed to Hans and Tamme von Röbel, the interest over 14 shillings. At Schmetstorp the rent and the interest flowed over 3 counters, over 8 bushels. The lease went to Ritter Wichusen for 22 bushels. The lease of 18 bushels went to Albert Rathenow, second mayor of Berlin. Likewise, 2 wispel and 1 bushel went to the St. Martin altar of the Nikolaikirche in Berlin . The rent and the interest went to Fritz and Klaus von Bredow for 6 counters. The lease flowed to the mayor from 6 Hufen. The von Bredows received the bede, the income as judge of the higher court and they were entitled to the plowing of the peasants . They had acquired these rights over 30 years ago from Knight Betkin Wiltberg. The payments from the turning pieces flowed to the mayor and von Bredows, the loan payments from the mayor to that of Bredows. All payments listed were to be made annually.

Since the land register did not give the number of full farmers, no statement on the number of inhabitants could be made. In the Middle Ages , the middle and large farmers determined the village life. With the Hans Smides Hoff, the margravial fief register from 1431 handed down the first name. The early landlords lay in the dark of history. The state description of the Mark Brandenburg from 1373 recorded the Bredow main line as castle seated with castle and spots Friesack ( Nobiles de Bredow cum castro et opido Frizsak ). It cannot be ruled out that the Bredows acquired the Ritterhof Buch with the loan of 1342 in addition to the rights and taxes mentioned in the land book of 1375 and that the seller was Betkin Wiltberg. There is no concrete evidence of this. Thus Ritter Schmetstorp was the first owner of the Ritterhof known by name. According to the fief register of 1416, Henning von Krummensee and his brother followed him. The assignment to the archdeaconate of Bernau , which can be seen in the register of the Diocese of Brandenburg from 1459 , was already in effect when the village was founded.

Among the von Röbels to the von Pölnitz (Pöllnitz)

The lords of Röbel were among the leading nobility of the Mark Brandenburg in the 15th century . Tamme and Czander von Robil and their cousins and brothers paid homage to Frederick VI in August 1412 . from Nuremberg . The new captain and administrator of Brandenburg, from 1415 as Friedrich I, the first Margrave of Brandenburg from the House of Hohenzollern , confirmed their enfeoffments . This included 16 counted pieces and the Higher Court in Windischen Buck as well as the 8 Hufen large Ritterhof in Blankenburg , probably the main residence of this Röbellin line.

The lap register of 1450 listed 45 hooves for Wendeschen Buk . Of these, 12 free hooves belonged to the von Röbel men. They also owned land in villages in the area ( Birkholz , Blankenburg, Hohenschönhausen , Schöneiche , Schönfließ and Wartenberg ). Over the following centuries the estate book were nearly all other full-farmers - and Kossäten incorporated courtyards. A document from April 5, 1459 named Tamme Robel to buck , one from September 10, 1475 Tomas Röbel to Buck u. Hanß Röbel to Blankenburch . However, it was not until April 8, 1483, that the mortgage was granted that Thomas, Achim, Diderike, Hansen and Claus von Robel lived here. Buch had become the headquarters of the Röbel family branch.

The late medieval agricultural crisis of the 14th century and the increasing demand for grain since the middle of the 15th century prepared the ground for the emergence of the manor . This characterized the following criteria: a largely coherent estate complex, which was mainly managed independently and in which exclusively the landlord exercised the jurisdiction and the compulsory labor of the rural population exceeded in importance the taxes to be paid in kind and money . The previously free full farmers became subjects. The process began with full force in the early modern period , the beginning of which could be determined in this country with the introduction of the Reformation in 1539–1541. The history up to the end of the 19th century was increasingly shaped by the changing owners of Gut Buch. They expanded the place into a representative seat of nobility . Some of the feudal lords played a prominent role as high officials in the history of the Mark Brandenburg and the Kingdom of Prussia .

In 1540 the general visit began, a recording of the inventory of churches and monasteries as well as the condition of the parishes. This reported that the village church Karow was a branch of the von Buch . It was probably during those years that the villages on the southwestern edge of the Barnims , north of Berlin - Kölln , were assigned to the archdeaconate of the royal seat . From the time of the Reformation, there was information about the offices of von Röbels. The visitation protocol named Hans († 1563) and Valentin († 1559) von Röbel as church patrons of Buch and Karow. Hans also acted as a Brandenburg council. After the last takeover of taxes in 1541 and the death of his brother Valentin in 1559, he became the sole fief recipient in Buch. From then on, the Röbels referred to themselves as heirs or inheritors of Buch.

Hans von Röbel's sons also held important positions: Joachim as field marshal in the service of Kaiser , Kursachsen and Kurbrandenburg and Zacharias von Röbel (1522–1575) as commandant of the Spandau fortress . Zacharias died three years after his brother without leaving children. When the inheritance was divided on October 20, 1587 among the six sons of Joachim, book fell to Zacharias von Röbel (1564-1617). The records of the Bucher Hausstellen for the year 1598 resulted in an estimate of 30 families with 150 inhabitants. Later in the year a plague epidemic ( Latin pestis , 'epidemic', also 'plague') broke out with 152 fatalities. From the note in the church book it was not clear whether the number was only valid for one village or the entire municipality of Buch-Karow. In 1608 Karow was still desolate , as was the nearby Birkholz.

From Bartholomäus Augustin († November 3, 1605), the first documented sexton teacher, the educational system could be proven in book. According to the church visit of 1600 there was a rectory and the construction of a sexton's house was ordered. Since a note from 1672 confirmed the existence of the latter, the building, which also serves as the village school , must have been built sometime between these two years. According to the table The Bucher Höfe in the history of the Berlin suburbs Buch and Karow , both houses were located to the west of the church on the site of the later estate gardening, with the sexton replacing the church barn.

The Thirty Years' War , which broke out in 1618, initially hardly affected the country. It was not until 1626 that the Thirty Years War began to suffer in the Mark Brandenburg . The country moved into the focus of foreign interests and, because of its central location, became a transit area. In addition there was a lavish Georg Wilhelm , Elector of Brandenburg (1619–1640) and a lack of military strength. It made no difference whether enemies or allies passed through. The Danish , Imperial , League , Swedish , Polish , Russian and Saxon troops devastated the march. They looted, robbed, murdered and raped, caused famine and epidemics.

The Barnim was one of the hardest hit areas. If the troops moved in, a contact person was required on site to organize billeting, food and pay. War commissioners were appointed for this, from which the Prussian district administrators later developed. In the Niederbarnim district , the knightly areas of a landscape were called circles from ancient times, one of them was Hans Dietrich von Röbel (1595–1654). But he couldn't prevent the neighboring town of Schwanebeck from lying desolate for several years. According to the church book, there was not a single wedding in Buch for about seven years from 1634 and only four children were born. It should be noted, however, that the influence of the church fell sharply during the war. At first epidemics dead, Hans Utes on Thursday after Bartholomi 1630 at 8 am, followed up in 1638 still 111 more.

| year | dead | Comment from Pastor Weigelius |

|---|---|---|

| 1630 | 23 | |

| 1631 | 17th | |

| 1636 | 11 | Woeful year |

| 1637 | 32 | Misery year |

| 1638 | 29 | Famine year |

| total | 112 |

Hans Dietrich von Röbel had been the heir of Buch since 1617, but lived in his Berlin house at Klosterstrasse 72. Only when the situation stabilized somewhat under Friedrich Wilhelm , Elector of Brandenburg (1640–1688), did he move to Buch. The first wedding after a long time on October 17, 1641 was accompanied by strange circumstances. The widow of the previous owner, Ambrosius Schmedicke and Adam Gottschalk, celebrated at Kossatenhof 5. For the bride and groom to walk to the church, the undergrowth on the village street first had to be removed with a scythe. During the war, George Danewitz held the offices of the village schoolteacher and church leader. The Peace of Westphalia of 1648 ended the Thirty Years War.

After that, the development of the manor gained a new dynamic through the increased peasant laying. Around 1650, 18 of the 26 farm posts in Buch were vacant. The 4 Hufen large farms No. 2 and 3 enlarged Gut Buch to 20 Hufen. Anna Danewitz, the daughter of George Danewitz, married Michael Mewes from Neuenhagen in 1653 . This couple would become the ancestors of the many local Mewes. The church's crypt , donated by Hans Dietrich von Röbel, remained the only remaining architectural legacy of the noble family in Buch. He was buried there on June 19, 1654 as the first and last of his family. His successors Joachim Adolf (1595–1670) and Georg Christoph von Röbel were heirs of Altfriedland and Garzau and continued to live there. The Birkholz, Buch and Karow estates were initially managed by administrators; in 1669/1670 they were sold for 15,000 thalers .

The new squire Gerhard Bernhard von Pölnitz came from the old Vogtland noble family von Pölnitz and had already made a career under Friedrich Wilhelm, the Great Elector. In the eventful year 1670 Leopold I , Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire (1658–1705) appointed him baron , he probably moved straight to Buch and had the then much smaller palace park redesigned in the Dutch style . This corresponded to the zeitgeist, in addition, the baron had been trained in the United Netherlands and had married Eleonora von Nassau (* around 1620, † March 1700) there. As early as 1672, Johann Sigismund Elsholtz in Garten-Baw counted the park among the most beautiful in the Mark Brandenburg. In the same year the church patron had a new rectory built. Gerhard Bernhard died in 1679 and left the property to his wife, Baroness von Pöllnitz, who managed them alone for 21 years. The grandchildren Henriette Charlotte († 1722), Friedrich Moritz von Pöllnitz and Karl Ludwig von Pöllnitz inherited them after the death of the baroness in 1700 and leased the three properties. In 1717 Friedrich Wilhelm I , King of Prussia (1713–1740) declared all feudal estates of the knights and feudal shoulders to be their own .

Under Adam Otto von Viereck to von Voss

Friedrich Moritz and his brother Karl Ludwig von Pöllnitz sold Birkholz , Buch and Karow to Adam Otto von Viereck for 47,000 thalers in 1724 . This entrusted I. C. Albers with the creation of a field register for Buch and Karow. The lieutenant engineer made it in April / May 1725. Of the total of 45 local hooves, 14 knight hooves and 5 farmer hooves belonged to Gut Buch. The latter were among five desolate lying villages of Kossäten . Five still resident full farmers cultivated 3 hooves each, seven Kossaten one hoof each. The remaining 4 hooves were with the pastor . All hooves were within three spaces . Five cottages and the church owned some land outside of it.

The landlord and church patron developed extensive building activity. In 1724 he had the Buch palace park expanded in the French style and commissioned Friedrich Wilhelm Diterichs with the baroque conversion of the manor house into Buch Palace. Viereck, as President of the Kurmärkischen War and Domain Chamber at the same time the superior of the building inspector, Diterichs also entrusted the construction of the castle church Buch between 1731 and 1736 instead of the demolished village church. The renovations that were required at short intervals were mainly due to the leaky church roof. The rectory was built in 1740, the sexton's house around 1750 on the south side of Dorfstrasse. The Orangery Buch, built around 1760, completed the baroque design of the park. The village krug became the property of the estate in the middle of the 18th century, has been called Schlosskrug ever since and has always been leased.

In the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), typhus and smallpox broke out in 1758 , claiming 40 deaths in Buch and Karow. Adam Otto von Viereck died in the same year. On August 12, 1759, the battle of Kunersdorf raged only about 40 kilometers away . When Russian troops under General Gottlob Curt Heinrich von Tottleben besieged the Prussian capital in October 1760 , Buch was also affected. Johann George Ulrici, pastor of Buch-Karow (1740–1773) gave a detailed account of the events connected with it. For a few days, the residents observed the fighting from a distance and kept receiving terrible news from messengers and refugees. The people of Buch bravely opposed the first soldiers and fulfilled their demand for 30 thalers, which eventually turned into 60. The second troop of hussars and Cossacks threatened arson and extorted more than 250 thalers. They beat the pastor and robbed his house. Then the villagers decided to flee to the northern heath and finally to Bernau . On their return, the farmsteads, the castle and the church were looted, the church was damaged and the coffins in the crypt were desecrated.

In 1761, three years after the death of Adam Otto von Viereck, the estate was divided among his three remaining daughters. The father had stipulated that it should be done by lot. Birkholz, Buch and Karow fell to Amalie Ottilie (1736–1767), married to Friedrich Christian Hieronymus von Voss (1724–1784). In the same year, the farmers received four oxen from the king for their war losses, as well as compensation for the horses, the landlord replaced the pillage payments and Pastor Ulrici received 150 thalers from the church treasury in 1763. The Peace of Hubertusburg of 1763 confirmed the conquests of Frederick II , King of Prussia (1740–1786) in the Silesian Wars , but the country was financially and economically depressed. The recovery succeeded with a series of government measures, and Buch profited from the promotion of silk construction .

Hieronymus von Voss was in the Prussian service as secret legation counselor and envoy extraordinary in København (1750/1751), but mainly devoted himself to the administration of the estate. He had the church repaired, its red tile roof replaced by a gray slate roof and the interior completed with an epitaph for his father-in-law Adam Otto von Viereck. Shortly before her death, Amalie Ottilie von Voss donated Buch-Karow as entails . This required the Bucher Gutsfelder to be sorted out, which was carried out by a commission from the Chamber Court . The associated list of the livestock indicated 5 full farmers, 7 full and 3 semi-farms. With the listed 1775 Ziegelscheune, 1801 Brickyard named a new Commercial moved in.

Otto Carl Friedrich von Voss bought the Wartenberg estate , and after the death of his father in 1784, the Birkholz and Buch-Karow estates were added. He thus owned the largest non-governmental goods complex in the Berlin area. Otto von Voss maintained an on-off relationship with the Prussian state and was deep in feudal rooted thinking. At least he initiated from 1795, the separation of rural compulsory labor and natural duties in cash payments, he gave up his ownership of the farm land on. The remaining Buch farmers became owners of their farms . Therefore, scattered in the three fields using Zelgen had separation into larger fields together and the commons are divided. The starting point for this was the map of the Buch field meadows drawn up by Landmesser Thal in 1803/1804 . Theodor Fontane wrote an entire chapter about the fate of Julie von Voss , Otto's sister, in his wanderings through the Mark Brandenburg .

From 1785 onwards, Gut Buch managed the four Pfarrhufen and the church land on a long lease . The contract included the construction of a new rectory by Otto von Voss. The half-timbered building was built in 1788 on the south side of Dorfstrasse (today Alt-Buch ). This was preceded by an exchange of land with the parish in 1786. As a result, as well as by buying up farmsteads in 1809 and 1813, Otto expanded the park in the southwest to Dorfstrasse and in the west to the road to Pankestegen (today Wiltbergstrasse ). Additional areas were added to the east of the Mühlenweg (today the southern part of the Pölnitzweg ) until 1820 . The baroque and new parts were reshaped or designed in the English style . The Dutch garden remained largely unchanged. A pond was dug in place of the nursery moved to the southwest corner. The back of the orangery received a neo-Gothic extension around 1800 . As the patron saint of the church, he had the castle church repaired, and as the landlord, the kitchen house was built around 1810.

During the Napoleonic Wars (1805–1812), Buch experienced the escape of Friedrich Wilhelm III on October 25, 1806 . , King of Prussia (1797–1840) and repeated troop passes on the Uckermärkische Heerstraße . French soldiers quartered in the castle . The occupying power systematically plundered the country through extremely high contributions and requisitions . As a result, as well as because of the continental blockade and the French trade monopoly , the economy collapsed. The Prussian reforms that began in 1807 heralded the end of feudal and the beginning of capitalist structures, enabled the expulsion of foreign rulers in the Wars of Liberation (1813–1815) and the rise of Prussia to a great power.

In 1815 the margraviate was transformed into the province of Brandenburg . Otto von Voss prevented the construction of the Provinzial chaussee Berlin– Prenzlau (today Bundesstrasse 109 ) at the beginning of the 19th century in the middle of Buch in order not to disturb the idyllic village. So it led through Buchholz and Schönerlinde . In founded in 1818 Schäferei book the Guts took sheep farm to. Later called Vorwerk Bücklein , land outside the medieval village limits was settled here for the first time. On October 20, 1822, a fire broke out in the manor barn and destroyed six other buildings, including the sexton's house and the castle jug. The landlord caught a cold while extinguishing the fire, which he died of in January 1823. His wife Karoline Maria Susanne, née Finck von Finckenstein, passed away in the same month.

The heir and son Wilhelm Friedrich Maximilian von Voss (1782–1847) had the castle jug rebuilt in 1823 and the fire damage on the estate removed around 1830, while the kitchen was expanded to include the inspector's house. No information was found on the construction of the sexton's house. The new houses on the street Am Sandhaus , mentioned for the first time in 1839, enlarged the village area again; they were later called Kolonie Buch and then Sandhäuser . Since 1842 the Berlin – Stettin railway line ran from southwest to northeast roughly parallel to the Panke over the district. Friedrich Wilhelm Maximilian 1st Count von Voss-Buch (* May 3, 1782 - † February 28, 1847), who was raised in the counts in 1840 , left the inheritance to his younger brother Karl Otto Friedrich 2nd Count von Voss-Buch in 1847 for lack of children (September 26, 1786 - February 3, 1864). During the March Revolution of 1848 there were no special incidents in Buch.

The land map of the geometer Fielitz from 1857/1858 showed the municipality with 1078 acres and eight square rods . The following were recorded as the proportionate owners: three full farmers, two full and three semi- cottages , three Büdner , Gut Buch with one full farm and three cottages, mill, jug, blacksmith shop , church, pastor and sexton and school post. With the help of the card, Karl von Voss ended the transfer and separation that his father had begun by 1859. As a result, in 1860 the size of Buch Landgemeinde was given as 802 acres, including the Buch colony. As the last remnant of the commons, a drinking trough in the middle quarry and two sand and clay pits on Zepernicker Strasse and Am Stener Berg have been preserved. The areas, each one acre, continued to be used by the cooperative. The pastor and sexton of four farmsteads still received the bushel grain as a contribution in kind . The Buch manor district consisted of a total of 4595 acres including the areas in Karow and the Büchlein sheep farm. The forester's house in Buch managed the associated 2166 acres of forest.

Since Karl also died childless, the property passed in 1864 to the descendants of his uncle Albrecht Leopold von Voss, the family branch of Voss-Buch. In the time of Ferdinand von Voss-Buch (1788–1871) on February 3, 1864 as 3rd Count von Voss-Buch raised to the Prussian count and his wife Julie Karoline Albertine, née von Finckenstein-Madlitz († 1877), fell the construction of new farm buildings in 1865 and the servants' house on the estate in 1870 and the new construction of the Ausspanne around 1870. The Uckermärkische Heerstraße was fortified in 1878 between Prenzlauer Tor and Bernau, the Buch stop opened in 1879. The better transport connections enabled the colony to be built from 1880 onwards Buch northwest of the railway line between Viereck- , Hörsten- and Pölnitzweg. Gustav Leopold Siegfried Otto Hermann 4th Count (1871) von Voss-Buch (born April 11, 1822; † December 23, 1892 in Berlin) joined the estate in 1881 and, unlike his predecessor, lived in Buch. In 1881 he had the side wings of the palace extended by three meters and raised to two floors, with a slate covering replacing the roof tiles. After the sexton's house was rebuilt in 1886, the heavily decaying castle church was renovated in 1891. Gustav Graf von Voss-Buch had an accident on December 19, 1892 in a forest accident. He was followed by his younger brother Georg Richard Hugo 5th Count von Voss-Buch (born June 29, 1831). Through land purchases, Georg became the first representative of the Voss- Dölzig line and the Voss-Buch line came to an end. The water mill and running forge were demolished at the end of the 19th century.

From the sale to Berlin

In 1868 was James Hobrecht by the magistrate of Berlin been recalled in the budding imperial capital, a plan for sewage create disposal. At his suggestion, the area to be drained was divided into twelve individual radial systems , each with its own underground sewer network . The mixed wastewater and rainwater were directed into collecting basins by means of a natural gradient, from there pumped out of the city through iron pressure pipes , pre-cleaned in clarifiers and finally directed to sewage fields . Despite great resistance, the project was implemented from 1873.

In order to implement the last of the twelve sections, Carl Arnold Marggraf , Berlin city councilor and chairman of the sewer deputation, negotiated with Georg Graf von Voss-Buch about the acquisition of Gut und Dorf Buch. In 1898 the city of Berlin bought the approximately 5000 acres of land for 3.5 million marks (today around 24 million euros, adjusted for purchasing power ). The existing manor farmed the Berlin sewage fields west of the village center. The Rieselgut specialized in dairy farming , which is why mainly grass grew in the fields . The northern lands were merged with areas acquired later from Bernau , Schönerlinde , Schönow and Zepernick and worked on from the Hobrechtsfelde, which was completely rebuilt from 1906 .

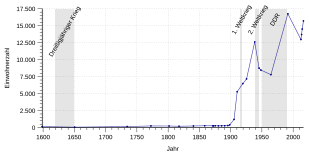

In 1898, the Berlin city council decided to use part of the estate for the construction of the sanatoriums in Buch . A decision that should turn the tranquil rural community into a handsome small town within a short period of time. The population rose from just under 400 to almost 6500 in 1919. Ludwig Hoffmann , Berlin City Councilor for Building Construction (1896-1924) designed five institutional complexes that were opened by 1929. First, the home for male breast patients was built 1901–1905, then the III. Municipal insane asylum 1900–1907, the old people home 1905–1909, the convalescent home for children 1909–1916 and the Buch-West hospital 1914–1916, completed 1927–1929 under the successor Martin Wagner . In addition, there was the municipal headquarters in Buch 1904–1913 as a supply and administrative system for all facilities and the institution cemetery in 1907/1908. Back then, Buch was the largest and most modern healing location in Europe.

Outside of the healing and care facilities, construction activity was lower after the sale to Berlin. Around 1900, the large barn on the estate, some houses for farm workers and the expansion of the castle mug to include a beer garden and pavilion . Because of the increased population, the classroom in the sexton's house was no longer sufficient . A school north-west of the breakpoint , built in 1903, expanded in 1908 and 1915 (today Am Sandhaus primary school) provided a remedy. In 1905 the palace park was opened to the public. Ludwig Hoffmann realized the expansion of the palace from 1905 into the summer residence of the Berlin Lord Mayor , the house for the sheep farm in 1908 and the imperial post office from 1908–1910. The rectory was replaced by a new building in 1911/1912.

Fed by the steam power plant of the municipal headquarters in Buch, built in 1908/1909, the Alt-Buch street shone in electric light for the first time in 1910 , and the volunteer fire brigade was founded in the same year . Between 1909 and 1916, which was Stettiner path from the station Pankow to the station Bernau part to a dam installed and expanded by two tracks. The former made it possible to cross the streets without crossing, the latter the structural separation of the long-distance and freight tracks from the suburban traffic. In the course of the expansion, the Buch train station was built in place of the 1912–1914 stop . The Vorwerk zu Schönerlinde called Kleinerlinde was first listed in 1765. Gut Buch set up a homestead in the neighboring village in 1831 . This was mentioned in the Official Gazette of 1846 and listed a fireplace with ten inhabitants. Before 1920, under the name Vorwerk Lindenhof , it became a book estate district .

The First World War broke out in August 1914 before the IVth Municipal Insane Asylum opened . Therefore, it was hastily rededicated to a reserve military hospital. Of the maximum capacity given as 1,800 patients, only 890 beds were available in October 1914. In addition, there was the problem of a lack of surgical treatment options, since the institution had been planned as a psychiatric clinic . The occupancy rate fluctuated greatly during the course of the war, with a total of around 33,000 people passing through the hospital. During this time, the actress Tilla Durieux worked here , first as a Red Cross helper, then as a nurse . In A door is open, she described what was happening on site, that the war spread its horror outside the trenches. Most of the deceased were returned to their homeland, 212 found their final resting place in the Buch Ehrenfriedhof . There are also locals, 86 Dead demanded of World War II until his death in 1918. The lack of care in the psychiatric hospitals of Berlin during the four years of the war led to an extremely high mortality rate , so the Municipal mental hospital on June 1, 1919, instead of IV. A Convalescent home opened for chronically ill children. For the nursing staff, as for the farm workers, the servants' ordinance applied until 1918 .

From the formation of Greater Berlin

At first Berlin refused to grow beyond the amalgamations made between 1861 and 1881. With the financial strengthening of the suburbs through the influx of better-off people and industry, the tide turned from the 1890s. The surrounding districts also wary of their autonomy. In the 1910s it became clear that cooperation in the Berlin area was necessary. This enabled the foundation of the Greater Berlin Association on April 1, 1912. Due to the oversizing, his work soon concentrated on a smaller area around the Reich capital. The association could not meet the expectations placed on him. The experiences in the First World War and the post-war period as well as the historical time window immediately after the November Revolution in 1918 enabled an administrative reorganization.

The ideas about the expansion of Greater Berlin differed greatly. Hence, the future status of Buch was unclear. In this situation, the residents' assembly of April 29, 1919 in the Groll'schen Saal spoke out clearly in favor of incorporation. Due to the close interweaving, the city council of Berlin already administered the village, estate and hospitals, the people of Buch already felt like Berliners and saw the advantages of merging. The census of October 8, 1919 showed 6479 inhabitants, of which 3917 in Buch- Landgemeinde and 2562 in Buch- Guts Bezirk . The April 27 in 1920 by Parliament of the Free State of Prussia adopted law on the formation of a new township Berlin took a good five months later on October 1 in force. The town of Buch succeeded in what was denied the Zepernick and Bernau who were also willing to join . Previously, the district Niederbarnim in the administrative district of Potsdam the province of Brandenburg, belonging, became of her, a district of Pankow of Berlin.

In order to meet the housing shortage after the war, the Berlin building administration had a new residential area built in Buch as one of the first measures. In 1919–1922, a settlement with terraced and semi-detached houses was built on the Karower Chaussee / Lindenberger Weg triangle based on a design by Ludwig Hoffmann . In the 1920s, the area north of the old people home was opened up with small single-family houses. A first, modest business center developed around the station. Around 1925, the city counted ten grocery stores, four bakers, butchers and hairdressers as well as two drugstores. The restaurants were visited by both locals and day trippers. Together with the railway line, Buch went down in the history of the Berlin S-Bahn , on August 8, 1924, the first (electric) S-Bahn train ran between the Szczecin suburban railway station and the Bernau railway station . The A 42 bus line, opened in 1929 between Ostseestrasse and Lindenhofstrasse (today Wiltbergstrasse), expanded local public transport .

In 1925/1926 Alt-Buch received a new pavement and the Pankebrücke received a repair. In 1927 the extensive construction work continued, the rectory added an extension to the parish hall , the park and the orangery were generously renewed, the castle and the castle church were extensively renovated. To the south of the village center, between Karower Chaussee and Lindenberger Weg, the Second Municipal Central Cemetery opened in 1925, but could not be used as intended. Politicians saw this as an opportunity to keep the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Brain Research (KWI for Hirnforschung) in Berlin and offered the Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science (KWG) a long-term long-term lease for the northern part. In 1928 the KWI temporarily moved into house 231 of the Buch sanatorium . In the meantime, Carl Sattler erected three new buildings on the site by 1930, which were ceremoniously opened on June 1, 1931. Institute director Oskar Vogt and department head Cécile Vogt concentrated on the anatomy of the brain within neurobiology , department head Nikolaj Vladimirovič Timofeev-Resovskij's specialty was genetics . From this point in time, the care of the sick and those in need of care was linked with research and teaching at the Buch medical location. The neurological research clinic for the KWI and the school extension, both from 1932, were among the few new buildings built in the early 1930s .

time of the nationalsocialism

With the takeover of power on January 30, 1933, the era of National Socialism began . The National Socialists quickly subordinated the treatment of patients and staff as well as the research content in Buch's medical facilities to their political ideas. During the twelve years, the hospitals and nursing homes have been subject to a permanent change in uses and names, only shown in extracts. From April 1933 a great wave of purges rolled through the institutions. The law on the restoration of the civil service of April 7, 1933 served to legitimize the injustice. Wilhelm Klein, Berlin State Commissioner for Health Care, was in charge of the organization, while the Main Health Office in Berlin was responsible for the organization. Around one hundred Jewish and / or politically unpopular employees were fired. These included the three medical directors Karl Birnbaum (1878–1950), Lasar Dünner (1885–1959) and Otto Maas (possibly emigrated to Palestine ) as well as the chief physician of the Waldhaus Buch Reinhold Hirz (* 1875). After that there were great difficulties in filling the many vacancies appropriately and at all. The medical director of the children's hospital in Buch , Iwan Rosenstern (1882–1973) was initially allowed to stay as a veteran of the First World War. In the course of the dissolution of the institution on February 28, 1934, he was also released. The Hufeland Hospital, which later became the Prenzlauer Berg Clinic from Prenzlauer Berg , moved into the premises by around October 1934 , and the name also moved with it.

Director Oskar Vogt refused to dismiss Jewish or left-wing employees at the KWI for Brain Research . In March and June 1933, hordes of the Sturmabteilung (SA) broke into the building and arrested employees. House 231 of the Buch sanatorium was used by the SA as a barracks and torture facility, as evidenced for May 1933. Protests by the KWG prevented further attacks. The hostility towards Cécile and Oskar Vogt culminated in 1935 when they were forced to retire . The style of the Catholic Mater Dolorosa Church , built in 1934/1935, still followed the Expressionism of the late 1920s. The last thatched-roof building, the former shepherd's house at the eastern exit of the village, was demolished in the 1930s.

The inhuman distinction between “inferior and superior life” brought u. a. the law for the prevention of hereditary offspring , which came into force on January 1, 1934. The aim was the compulsory sterilization of all people considered to be hereditary, work-shy, alcoholic or drug addicts. First of all, everyone in question and their relatives had to be recorded. For this, every psychiatric clinic in the country received a herbalist. Werner Pfleger , who came from Wittenau , took up the post at the Buch sanatorium . In principle, all of the remaining doctors, starting with the new medical director Wilhelm Bender (1900–1960), showed great enthusiasm for the implementation. The reports went to the responsible hereditary health or hereditary health supreme court, a specially newly created instance. There, a judge and two attending doctors made decisions based on the files; they rarely heard the victims themselves. In the end, hundreds of Buch patients were forcibly rendered sterile by surgery or X-rays.

In the absence of a successor, Oskar Vogt remained provisional director of the KWI until 1937, after which the Vogt couple and some employees moved to Neustadt in the Black Forest . There they founded the private institute of the German Brain Research Society . The new director of the KWI, Hugo Spatz , shifted its focus. In addition to the investigation of neurological diseases and tumors, the scientifically unsustainable eugenics and race research moved into focus. Although these were not inventions of the National Socialists, they served to justify their policies. The Buch hospitals were subordinated to the Pankow district in 1938 .

Wilhelm Bender and the three other directors of the Berlin sanatoriums and nursing homes ( Herzberge , Wittenau and Wuhlgarten ) participated directly in the nationwide preparation of the T4 campaign . One of the corresponding meetings took place in Buch. The circular of October 9, 1939, co-authored by Bender, requested the psychiatric clinics to provide information about their facility and patients. His own institution was occupied by around 2,800 people at that time. In addition, more than 1,500 Buch patients were accommodated in the Obrawalder and in private institutions due to a lack of space . How many of these were reported could not be determined. On the basis of the lists sent to the T4 headquarters, experts decided who would be murdered. From the surviving sources, 731 people are known by name only for book, who were sent to the gas chambers of the killing centers . The real number is likely to be higher. The sanatorium also gave up the patients who were allowed to continue to live. On November 1, 1940, the facility was vacated and closed. By decree of February 28, 1941, the Hufeland Hospital moved here and brought the name with them. From April 1, 1941, the municipal hospital was gradually set up in the former children's hospital .

The Buch sanatorium and nursing home and the KWI for Brain Research worked closely together. Julius Hallervorden , from 1938 professor of neuropathology at the institute, also remained the prosector of the Brandenburg-Görden Provincial Psychiatric Institute . Immediately next to it was one of the murder sites of Aktion T4, the Brandenburg killing center . Hallervorden suggested that the prosecution there send him as many brains of the murdered as possible , which happened in several installments. Hermann Wentzel, Buch section assistant and nurse, took brains from the Hartheim killing center . In total, the KWI received at least 700 organs. After Aktion T4 became public and because of disputes over competencies, it was officially discontinued on August 24, 1941.

The war memorial on the western edge of the palace park, inaugurated in 1933, gave an idea that the fascists had war in mind. The ration cards issued throughout the Reich at the end of August 1939 caused rumors and speculation to swell. On September 1, 1939, the Second World War began with the attack on Poland . Forced laborers , including prisoners of war , were housed on the estate, in the Buch sanatorium and nursing home or its successor facility, and in the barracks at Am Sandhaus . They mainly worked in agriculture and hospitals, in the cemeteries and in the train station . Their misery took place in public and could not remain hidden from the books. The district was initially spared the immediate effects of the war.

In 1943, the Allies launched massive air raids on Berlin . The area bombing was directed against the war economy and the population. The fact that bombs fell on the district at all was probably due to the anti-aircraft guns stationed here . The basement of the orangery and the cellar of the barn on the estate served as air raid shelters . On November 18, 1943, an incendiary bomb hit the castle church , the burnt-out tower fell inside and destroyed it as well. Of the sanatoriums, the Hufeland Hospital was hardest hit. Damage occurred u. a. in a ward block, a laboratory, the chapel and the X-ray house. On May 7, 1944, the bombs mainly destroyed houses in the neighboring suburb of Buch , but some houses also burned down in Buch. On March 23, 1945 in the Ludwig Hoffmann Hospital, the roof trusses of a ward block and the water tower in its entirety, and that of a farm building in part, fell victim to the flames. Compared to other Berlin districts or German cities, however, the devastation in Buch was minor.

Sanatorium and nursing home at Buch Haus 231, a torture center for the SA in 1933

Memorial plaque for the victims of Nazi forced labor, Wiltbergstrasse 37

When I grow up, then ... - In memory of the victims of Nazi euthanasia crimes at the KWI for Brain Research , by Anna Franziska Schwarzbach , 2000

Memorial plaque for Dr. Walter Schönebeck at the Schlosskirche in Buch

1945 to 1990

The Red Army reached the Oder on January 30, 1945 , crossed the frozen river and built a bridgehead in Kienitz . As a result of the approaching fighting, the A42 bus line ceased operations on April 12, 1945. On April 16, 1945, the decisive advance of the 1st Belarusian Front to the Battle of Berlin began . Shortly before the arrival of the Soviet troops, the field gendarmerie shot and hanged so-called deserters . One day after Bernau , on the morning of April 21, 1945, the Red Army soldiers were in Zepernick . An S-Bahn train came under artillery fire between the suburb and Buch, whereupon the entire route ceased. In order not to endanger the sick and wounded in the sanatoriums, Marshal Georgi Konstantinowitsch Zhukov refrained from using artillery when attacking the district. Prisoners of war and forced laborers who had freed themselves in the meantime indicated the last nests of resistance of the Germans. At noon on April 21, 1945, Buch was liberated. Soviet soldiers looted, abused and killed civilians, raped women and girls. On the other hand, they handed over wounded German prisoners of war to the Buch hospitals and provided children with food. Many people committed suicide or were killed by withdrawing German armored troops on refugee treks. On May 2, the German troops surrendered in Berlin, and on May 8, 1945 the war was over.