History of Italy

The history of Italy in terms of human settlement in the Apennine Peninsula and the islands surrounding it can be traced back 1.3 to 1.7 million years, with modern humans appearing in Italy around 43,000 to 45,000 years ago and several millennia alongside the Neanderthals lived. Until the 6th millennium BC Hunting, fishing and gathering formed the basis of its existence. Around 6100 BC . AD brought the first group from outside the peninsula - probably by sea from Southeast Anatolia and the Middle East - the agriculture with; the hunters and gatherers disappeared. In the 2nd millennium BC A development began that made the villages into early town-like settlements, and the societies showed clear traces of hierarchies for the first time .

The history of Italy, as documented by written sources , only begins after the colonization by Italian peoples . Alongside them, the Etruscan culture , whose origin is unclear, experienced around 600 BC. Their heyday. In the 8th century BC The Greek colonization of the southern Italian mainland and Sicily had begun, Phoenicians settled on the west coast of the island . These colonies later belonged to Carthage .

From the 4th century BC BC began the expansion of Rome , 146 BC. Chr. Were Corinth and Carthage destroyed, the conquest of the Mediterranean, and later parts of central and northern Europe brought cultural influences and people from across the kingdom and neighboring areas to Italy. The peninsula formed the center of the Roman Empire and remained so, with some restrictions, until the fall of Western Rome around 476. In the process, the agricultural economic base, which had initially consisted of peasants, was transformed into a system of spacious latifundia based on slave labor . A dense road network connected the expanding cities, thanks to which the exchange of goods, but also the dependence on external goods such as wheat and olive oil from North Africa, increased. In late antiquity , in addition to slavery and the free peasants in the country, forms of attachment to the land appeared, such as the colonate , although a distinction was still made between free and unfree colonies around 500 ( Colon Edict of Anastasius ). In the 4th century Christianity was established as the state religion.

From the 5th century, Italy came under the rule of Germanic tribes , the population decreased drastically by around 650, briefly Ostrom conquered the former core area of the empire in the 6th century. In the 8th century, the north, ruled by the Lombards for about two centuries, was annexed to the Frankish Empire , later to the Holy Roman Empire , while Arabs and Byzantines ruled in the south, and Normans from the 11th century . In most regions continued in the early Middle Ages of feudalism through its relationships with the late Roman Kolonat are extremely complex. The northern Italian municipalities, which found themselves together in the Lombard League, were able to break away from the influence of the empire in the 12th and 13th centuries and establish their own territories. Of this multitude of territories, the most important were Milan , the naval powers Genoa and Venice , Florence and Rome, as well as southern Italy, which was partly French and partly Spanish. The fact that the Bishop of Rome rose to Pope of the Western Church, the separation from the Eastern Church came in 1054 and the Pope got into lengthy arguments with the Roman-German kings , then with the French King Philip IV , played a central role . The latter forced the Pope into exile in Avignon from 1309 , which lasted until 1378. The return of the popes to Rome accelerated the construction of the Papal States in central Italy, the political developments on the peninsula significantly influenced by the 1870th

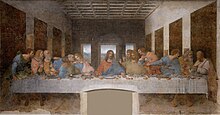

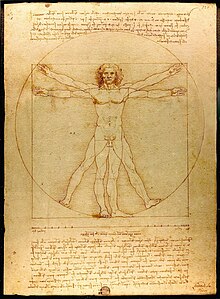

From the 14th to the 16th centuries, Italy was the economic and cultural center of the Renaissance . Five leading powers had emerged, with the Papal States playing a role of their own. From the late 15th, but especially in the 16th and 17th centuries, the major European powers - France, Spain and Austria - repeatedly interfered in Italian politics. They sealed off their markets to different degrees from foreign goods. At the same time, the Ottoman Empire exerted heavy military pressure, especially on the Republic of Venice, from the late 14th century . Nevertheless, the Italian cultural metropolises, above all Rome, Florence and Venice, radiated far beyond Italy and Europe.

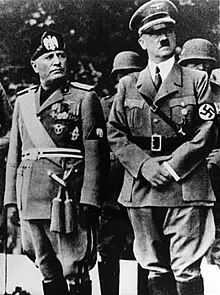

After four centuries of fragmentation and foreign rule, the peninsula was politically united as part of the national movement of the Risorgimento . The modern Italian state has existed since 1861, Veneto and Friuli were added in 1866, followed by Julisch Venetia (Trieste and Gorizia), Trentino and South Tyrol after the First World War . Italy waged colonial wars mainly in Libya (independent in 1951) and Ethiopia ( Battle of Adua in 1896, War of Abyssinia 1935/36). From 1922 to 1943, the fascists ruled Italy under Benito Mussolini ; in the last two years of the war, the German National Socialists controlled large parts of the country until it was liberated by the Allies .

In 1946, the Italian people decided to abolish the monarchy in favor of the republic . For the first time women were also allowed to vote. Since then, frequent changes of government have shaped the political culture, until the beginning of the 1990s with the continuous participation of the Democrazia Cristiana . Up until the end of the Cold War, disputes over Eurocommunism , partly militant political disputes, the contrast between northern and southern Italy, the influence of the Catholic Church , but also corruption right up to the political leadership groups and organized crime all point to some of the central lines of conflict in the Society. The collapse of the old party system and a constitutional change in the wake of the Tangentopoli affair at the beginning of the 1990s marked a political turning point and the transition to the so-called Second Republic.

Prehistory and early history

Paleolithic: hunters, gatherers, fishermen (1.3 million years old)

The excavations of Pirro Nord in Apulia , where the oldest human traces of Italy were found, show that hunters and gatherers lived there 1.3 to 1.7 million years ago. Italy has been inhabited continuously for around 700,000 years. Until the 6th millennium BC Hunting, fishing and collecting formed the basis of existence, with hut-like structures in addition to caves as living quarters near the French-Italian border as early as 230,000 years ago. The use of fire has been archaeologically proven since that time.

In the Middle Paleolithic , all of Italy was inhabited, with the exception of the islands of Sardinia and Sicily. Cro-Magnon humans were first recorded 45,000 to 43,000 years ago . Two teeth from the Grotta del Cavallo were dated accordingly and are considered the oldest evidence of the existence of anatomically modern humans in Europe. A few millennia later, the Neanderthals disappeared . After the end of the Würm Ice Age , sedentariness increased, especially on the coasts, where fishing dominated. In addition, shepherd cultures developed in the high and low mountain regions. The first Neolithic culture in southern Italy was the cardial or imprint culture , which began around 6200 BC. BC by influences from the eastern Mediterranean. By comparison with the land requirements of similar societies, a number of 60,000 human inhabitants could be calculated as a rough approximation. The men were on average 1.66–1.74 m tall, women 1.50–1.54 m tall.

Neolithic: Agriculture and Villages (from 6100 BC)

The first arable farmers settled between 6100 and 5800 BC. In the south of the peninsula. They came from the Greek islands, especially from Crete, from southern Anatolia and the Middle East. Mesolithic and ceramic cultures still existed in the northwest around 5500 BC. Next to each other. Different types of villages arose, with long-distance trade in obsidian and hatchet . In Neolithic Italy there are no signs of a hierarchization of society. Men were smaller than in the Paleolithic and Mesolithic, and they were never so small again afterwards. It was found that women were on average 1.56 m tall, men 1.66 m tall.

Metal Age, Immigration, Cities (from 4200 BC)

Around 4200 BC In Liguria, copper was the first metal to be processed; the Bronze Age continued in the late 3rd millennium BC. A. Proto-urban structures emerged for the first time, in Campania such a "city" was found near Poggiomarino , which existed from the 17th to the 7th century. This "bronze metropolis" apparently managed without defenses.

In the Bronze Age (approx. 2300 / 2200–950 BC) numerous cultures can be identified, whose assignment to the peoples that appear in the earliest written sources is not always certain. Around 1500 BC In addition, there was again strong immigration, the villages were reinforced. Finds such as those in La Muculufa in Sicily (near Butera ) document viticulture. The Iron Age , and occasionally the Late Bronze Age, is considered the formatting phase of the tribes that appear in the written sources . The greater number of weapons additions indicates the increasing power of a warrior elite. At the same time, there is extensive long-distance trade as far as the eastern Mediterranean. Etruscans and Greeks conquered contiguous territories based on cities, a development that soon spread throughout Italy and culminated in the rule of Rome.

In northern Italy lived in the 5th century BC The Celts who had just immigrated (Latin Galli ), then Lepontier and Ligurians , in the northeast Venetians . Central Italy was from Umbrians (in present-day Umbria); Latins , Sabiners , Faliskern , Volskern and Aequern (in today's Latium ) and Piceners (Marken and northern Abruzzo). In the south there were Samnites (southern Abruzzo, Molise and Campania ); Japyger and Messapier in Apulia ; Lucanians and Bruttii . The Sikeler colonized the eastern part of Sicily. Many of these peoples were of Indo-European origin, some were considered Aboriginal . The Etruscans in central Italy were not Indo-Europeans, possibly neither were the Sicans in Sicily. Sardinians lived in Sardinia , which may correspond to the earths in Egyptian sources.

From the 8th century BC The Greek colonization of southern Italy began. Numerous cities were founded both on the mainland (including Taras , Kyme , Metapontion , Sybaris , Kroton , Rhegion , Paestum and Naples ) and on Sicily ( Naxos , Zankle and Syracuse ). The Greek populated areas were called Magna Graecia (Greater Greece). A holdover is the still spoken Griko today .

The Carthaginians , who had developed into an important maritime and trading power, founded colonies on Sardinia as well as on Sicily . They got caught during the 6th and 5th centuries BC. In persistent conflicts with the Greek colonies , especially with Syracuse . On the other hand, they were temporarily in alliance with the Etruscans. It was also with Rome until 264 BC. A good relationship. Carthage and Rome closed around 508 BC. A first treaty, 348 and 279 BC. More followed.

Rome

Italy in the expanding Roman Empire (4th century BC to 2nd century AD)

In the 8th century Rome was a small rural community that grew out of several villages. According to traditional tradition, it shook in 509 BC. From the royal rule and the dominance of the Etruscans. In mythical memory, the expansion began in the battle with the Sabines , then against the city of Alba Longa . The emergence of the patricians and the plebeians , as well as the religious institutions, such as the priesthood of the vestals, can be traced back to this early phase . The Romans attributed the construction of the Cloaca Maxima or the Temple of Jupiter to the Etruscan King Tarquinius Priscus . With the end of the monarchy, the Senate assumed the most important role in the emerging state.

Rome extended his dominion first over central Italy, then to an empire over the entire Mediterranean area , and finally to the North Sea area and the Persian Gulf . Only after three wars (343–341, 327–304 and 298–290 BC) succeeded in subjugating the Samnites . With the victory over the Hellenistic king of Epirus , Pyrrhus I , in 275 BC. Rome began to break the purely Italian framework and to expand its power.

This expansion was already overwhelming in the first two Punic Wars , which with an interruption from 264 to 201 BC. The city's resources continued so that it was dependent on the help of the allies. Rome waged further wars against the Hellenistic empires in the east (200 to 146 BC), the Gauls of Northern Italy, whose territory was in 191 BC. BC became the province of Gallia cisalpina , but also areas in southern Gaul. 175 BC Liguria followed , then the Greeks in southern Italy and the Numidians in North Africa, after Carthage in 146 BC. Had been destroyed. Finally, the expansion to Asia Minor (from 133 BC) and the Iberian Peninsula (until 19 BC) followed. 58 to 51 BC Chr. Was conquered Gaul , advanced the frontier to cross the Rhine, eventually followed (but only in the early imperial period) Britannia .

Neither the centralization on Rome nor the power and administrative apparatus were suitable to control a territorial state of this size. In many cases, social and property relations also brought the empire to the brink of breaking up. Peasant and slave revolts (especially in 135, 104 and 73–71 BC) were the result of the fundamentally changed living conditions and the extreme inequality in the material and legal conditions within society. In addition, there was an increase in the influence of Hellenistic culture , and later also of the cultures of the Middle East, which a conservative Senate group who was reluctant to change perceived as a decline in values.

There was also another problem: Rome's victory was only possible through troops from the allies. However, since Rome refused its allies the legal equality, there were unrest at the end of the 2nd century and 90/89 BC. To the alliance war . Despite their defeat, the municipalities of Italy received Roman citizenship, 42 BC. The previously excluded cities of the Po Valley received this right . With the census of 29/28 BC Finally, all Italians were entered in the citizen lists. This made Italy a unified legal area preferred to the rest of the empire. This state of affairs lasted until AD 212, when all citizens of the empire were granted Roman citizenship and the duties attached to it. In addition, Italy, especially Rome, was an economic area to which almost all provinces were oriented. At the same time, it had to bear less and less the burden of defending the gigantic empire.

However, until the reign of Augustus, Italy suffered from severe power struggles that began with the struggle between Sulla and Marius and that were preceded by social struggles associated with the Gracchian reforms . They reached back to the early 5th century when the office of tribune was created. These civil wars reached a further climax with the fighting, from which first Gaius Iulius Caesar , then Augustus emerged victorious.

Pax Romana, Administration and Economics (1st to 2nd centuries)

The subsequent long peace phase ( Pax Romana ) in Italy allowed economy, arts and culture to flourish. The population density would not be reached again until centuries later. The achievements of Rome in the field of law, administration and art have profoundly shaped Western civilization .

The inadequate organization of the administration and the military was fundamentally changed by the early emperors. Augustus divided Italy into eleven regions . Most of the republican institutions were formally reinstated, but they remained largely dependent on his decisions and changed their character to administrative activity. However, the Senate in Italy retained some privileges, such as the disposition over the minting of bronze coins from 15 BC onwards. BC, the disposal of the temples or the management of the aerarium Saturni . The tribunes of the people retained their rights, but were formally subordinated to the Senate, reversing their previous position, but in fact to the Emperor.

While there was only a rudimentary administration in the republic - there were no principles, apparatus or trained personnel - this changed under the emperors. Claudius relied heavily on freedmen in administration (they lost their influence under the Flavians ), Domitian and Hadrian more on wealthy knights ( equites ) , i.e. the group of traders, tax farmers and the urban middle class for whom the republic never found an adequate job would have. Vespasian already drew more provincials, Trajan drew men from the East into the Senate. In particular in the financial administration there was a professionalization, especially when the Roman fiscus took over responsibility for the income from the provinces. A kind of central administration was created.

From the 2nd century onwards, the consilium principis , which was not easy to grasp, acted as a mediator and advised the emperor informally. Hadrian brought in lawyers for the first time. In the late empire this role was taken over by the consistorium . In addition, the Praetorian Prefect exercised great influence, who was initially responsible for the emperor's security with his Praetorian Guard . He soon received judicial powers that extended beyond the military (under the Severians within a radius of 100 Roman miles around Rome, i.e. almost 150 km) and often acted as a general. Since Nero , he has had his own tax in kind, the annona, to supply troops . Administrative units that were difficult to understand emerged around him. Special areas such as the games or the libraries were only taken over by the responsible procurators . In Rome, a praefectus urbi led the urban cohorts and presided over urgent courts. The praefectus annonae was responsible for the food supply, the market supervision and shipping on the Tiber as well as the bakeries. There was also a praefectus vigilum that organized fire stations. The tasks soon became too complex, so that under Trajan subpraefecti were used, to which narrower tasks were delegated.

In Italy the Praetorians watched over security. Tiberius brought them to Rome, only the prefects in charge of the fleets remained in Misenum and Ravenna . Municipal magistrates were right, and a court of last instance developed in Rome. The censors were no longer responsible for the road construction , but curatores viarum . The often chaotic finances of the cities have been subject to the curatores civitatis since Nerva . Around 120, the jurisdiction in Italy was to be centralized with four consulares , but the system did not establish itself until the end of the century in a weakened form. Overall, the massive self-enrichment that had resulted in republican times from the confusion of political, military and administrative offices and the short-term nature of the offices was reduced to a tolerable level. It was not until the end of the 2nd century that a relatively fixed hierarchy with corresponding salaries had developed.

Each city co-administered its surrounding area. In contrast to most provincial cities, the Italians were not subject to the obligation to pay tribute. Incolae , common residents or foreigners, and attributi who lived away from the cities had lesser rights. The connection to the overarching institutions was established by patroni , local notables.

The greatest relief for the Empire's economy was the end of the civil wars . This turned out to be quite different for Italy, however. There the politically and economically leading group had actually profited considerably from the supply of slaves and the tributes of the provinces, especially the large landowners. The imperial support of the municipia and the extensive imperial domains also benefited the wealth formation of the leading classes in the cities. But it was precisely the latifundia that led to the displacement of the peasants, to the depopulation of the country and to the expansion of pasture farming, which further promoted urbanization. In addition, olive and wheat growers faced stiff competition from Gaul , Hispania and Africa . The emperors, who came increasingly from the provinces since Trajan, for their part promoted the non-Italian regions at the expense of Italy.

The Italian economy was also burdened by the fact that most of the legionnaires still came from Italy and wars like the Trajans led to high losses and to settlement in the eastern provinces. Already Nerva , Trajan's predecessor, had given Italy a special place. Trajan moved the recruiting areas to the Hispanic areas and tried to counteract the emaciation of Italy. He therefore prohibited emigration from Italy, decreed that senators from the provinces had to invest at least a third of their property in land in Italy, and provided for peasants to raise children (alimenta). This alimentary foundation, which existed until the third century, provided monthly support to probably hundreds of thousands of children through interest and loans that Trajan granted to landowners. Ports, roads and public buildings received massive support, especially in Rome.

The insufficient supply of slaves to the latifundia and the low productivity of the goods led in the 2nd century to the fact that the large goods were increasingly divided and leased to coloni . The colonies paid taxes for their land in the form of money, goods or labor. Imperial domains were mainly in the south, but the provincial domains were more important.

Overall, it appears that the latifundia were less the cause of wealth than the fruits of the profits made in trade and production. Mines and quarries played an important role in this, but they were also operated in the provinces and not around Luna near Carrara , as there was fear in Italy of workers being withdrawn from agriculture. In terms of production, Italy remained the leader only in wool spinning, especially in the Po Valley, for example in Altinum and around Taranto . Glass and ceramics, lamps and metal goods, however, lost their leading role. In addition, there was the fierce competition between the country estates, the villae , which were becoming more and more economically independent , against which the small craftsmen who produced the lion's share of the goods could hardly compete. After all, the emperors promoted the brick trade with their building projects.

The barter largely disappeared, coins circulated in every town. For the first time, coin policy was of the greatest importance. Bronze coins were minted by the Senate, gold and silver coins by the Emperor. In 64 there was a first devaluation. Trajan was able to back the coin system with Dacian gold, from which Rome allegedly stole 5 million Roman pounds, i.e. more than 1,600 tons. But he devalued the copper coins by reducing the copper content. Hadrian's peace course stabilized the system in the long term, but even under Marcus Aurelius a significant inflation became noticeable, i.e. an increasing depreciation of the coins. This peaked in the 2nd half of the 3rd century. In addition, the extraction of precious metals was no longer sufficient, that is, it shook the value relation between gold and silver.

Little research has been done into the banking system. Transactions of coins could be arranged on paper, so that the difficulties and risks of transferring coins and bars were reduced. Foreign trade brought considerable income to the peripheral provinces, but the greatest volume was trade between the provinces.

Italy as a province in the Roman Empire, Christianization (3rd to 5th century)

The establishment of Christianity in the 4th century up to the status of the state religion , the founding of a second capital in the east and the division of the empire as well as the incorporation of Italy as an ordinary province, plus the political and military uncertainty that did not stop at Italy, characterized the changing situation in the country. Neither the persecutions, especially under Valerian and Diocletian , nor the pagan counter-reaction to the more Christian-friendly policies since Constantine by Emperor Julian could prevent the spread of Christianity. This religion, albeit often fissured but nonetheless ended in a few forms in the Middle Ages, together with its organs, became of central importance for the early Middle Ages .

The calculation of the number of inhabitants in antiquity causes considerable problems, so that the results diverge greatly. By 200 AD the Roman Empire could have had 46 million inhabitants, Rome at least 700,000, other estimates are considerably higher. For the 1st century, they range from 54 to 100 million for the empire and around 1.1 million for Rome. For the 3rd century, the assumptions vary between 50 and 90 million. Marc Bloch thought it was impossible to calculate the number of inhabitants. According to the older estimates by Karl Julius Beloch, Italy had 7 to 8 million inhabitants, Sicily with 600,000 and Sardinia with 500,000, but this number fell by 500 to around 4 million and by 650 to 2.5 million.

In 212, in the Constitutio Antoniniana, all citizens of the empire were given Roman citizenship, the previous preference for Italy was dropped. During the period of the so-called Imperial Crisis , which was marked by usurpations and increasing power of the military (see also Soldier Emperors ), Italy increasingly lost its role as the heartland of the empire; this development was to continue in late antiquity . In addition, Rome had to be militarily secured again after 270 with a city wall . Between 254 and 259 Germanic tribes reappeared on Italian soil for the first time, such as the Alamanni , who were repulsed in 259 near Milan and 268 on Lake Garda .

Analogous to the rest of the empire, the peninsula was divided into provinces under Diocletian ( list ). The Dioecesis Italiciana formed part of the Praefactura praetorio Italia , two Vicarii resided in Milan and Rome. The Regiones annonariae in the north of the peninsula, administered from Milan, served the maintenance of the imperial household, the Regiones suburbicariae administered from Rome served to supply Rome. The islands were included. A politically active Praefectus urbi administered Rome, which largely lost its function as the imperial residence under Constantine .

Theological disputes after the Council of Nicaea (325) between the Athenian western emperor Constans and the Arian-friendly Constantius II in the east soon also gave the two bishops of the metropolises of Milan and Rome a special position. Bishop Ambrosius of Milan gained considerable influence on imperial politics, while the Roman prefect gradually lost it, especially since many of the imperial incumbents tended to be more paganistic . Conversely, emperors, such as Valentinian I , interfered in the bishopric election in Rome. In addition, the clergy were exempt from duties and services, as well as from military service, with which they finally became a separate estate.

It is true that the first Jews can be found in Italy from the 2nd century BC onwards. The first synagogue was built around 100 AD in Ostia . In the 1st century, the number of parishioners was likely to have been around 60,000, of which 30,000 to 40,000 were in Rome. But around 300 there was a first ban on marriage between Jews and Christians at the Council of Elvira (can. 16/78), with the Codex Theodosianus (III, 7.2; IX, 7.5) this ban was valid throughout the empire Death penalty. In addition, the Jews were forbidden to wear clothing, slavery was forbidden (thus denying access to latifundia property and the manor) and the assumption of public offices. From 537 they still had to contribute to the financing of these offices.

Since Constantinople was founded as the capital of the East in 326 and the actual division into the Western Roman and Eastern Roman Empire in 395, Italy became an increasingly less important province. The western empire dissolved in the course of the migration of peoples under the pressure of the Teutons and Huns , the loss of economically important provinces, the army leadership that the emperor could no longer control and a spatially and socially fragmented society.

In November 401 the Germanic Visigoths of Alaric , who the Romans counted to the Scythians, like Alans and Huns, were in Italy for the first time. However, they failed before Aquileia, then in March 402 before the capital Milan. Honorius resided from then on in the safe Ravenna . On April 6, 402 the Goths almost suffered a defeat , Stilicho managed to withdraw from Italy, defeated them at Verona and later won them as an ally against Ostrom. It was not until 408, when the Rhine border collapsed, that Alaric threatened to move to Italy again, which he did after Stilicho's fall and his execution on August 22nd. In 410 Rome was sacked , but in 412 the Goths withdrew to Gaul .

After Honorius' death in 423, the Eastern Emperor determined politics in Italy. The Roman bishops, especially Leo I , managed to gain prestige both at the court of the West and that of the East. This was demonstrated by the invasion of the Huns under Attila in 452. In 455 , however, the Vandals sacked Rome and occupied Sardinia and Sicily. The Magister militum Ricimer ruled politics in the west for a few years before Constantinople supported Julius Nepos , who marched from Dalmatia to Italy. This in turn was overthrown by Orestes in 475 , who made his son Romulus Augustulus emperor, who in turn was overthrown by Odoacer in August 476 . With this, the Western Roman Empire ended de iure - at the latest with the murder of Julius Nepos in Dalmatia in 480. Odoacer formally recognized the rule of the Eastern Emperor and supplied his troops with land in Italy.

Church organization, diocesan hierarchy and Roman Empire

Without taking into account the differentiation between the official church and the community of the faithful, on the formal level a consolidation of the office structure and an expansion of the episcopate can be ascertained on the formal level , which in late antiquity affected every city. In contrast to many former provinces of the Roman Empire, this elevation of the city compared to the surrounding area remained characteristic throughout Italy. The borders between the Municipia often formed the later diocese borders, with monasteries such as Nonantola or Bobbio also being able to integrate their surrounding area.

The parish in the capital played a central role, traced back to the apostles Peter and Paul , and which enjoyed a special reputation. Between the bishops Damasus I (366–381) and Leo I (440–461) came the idea of a Renovatio Urbis , the resurrection of Rome as the Christian capital. Cyprian of Carthage already points to the legal continuity that refers to the chair of Peter at the church level. However, Ravenna and Aquileia also claimed to be among the oldest bishoprics that date back to the apostles. In the middle of the 3rd century, the first traditional synod of 60 bishops took place in Rome . At the end of the 6th century there were 53 churches in central and northern Italy, and 197 in the more urbanized south. Analogous to the state organization, two church provinces emerged with the centers of Milan and Rome. Aquileia was responsible for the areas up to the Danube . Ravenna was initially assigned to Rome, but under Justinian I , Bishop Maximianus of Ravenna was the first to accept the title of archbishop (archiepiscopus) and around 650 Ravenna was even withdrawn entirely from the jurisdiction of Rome by Emperor Constans II for a few decades .

Germanic peoples and eastern currents

Odoacer, Ostrogoths and Gothic War (476-568)

Even after 476, late antique structures initially continued to exist in Italy . After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476, Italy was first ruled by the rex Italiae Odoacer and was then from 489 and 493 the heartland of the Ostrogoths , who had invaded Italy under Theodoric on behalf of the Eastern Roman Emperor Zenon . Theodoric ruled formally on behalf of the emperor and separated civil and military power much more according to ethnic principles; the civil administration remained in the hands of the Romans, while the Goths exercised the military administration and were allocated land. It seems as if the privilege of the Ostrogoths prevented or even prevented the merging of the Roman aristocracy with the Gothic leadership group. The Ostrogoths were Arians and were therefore far removed from the ecclesiastical organs in Italy, which led Theodoric in his last years to imprison the Bishop of Rome or to have politically suspected people like Symmachus executed: after 519 the schism between Rome and Constantinople had been settled, the aging Gothic king increasingly feared that he might be betrayed to the East Romans. After the death of her father (526), his daughter Amalasuntha attempted a more Roman-friendly policy, but was murdered, which gave Emperor Justinian the opportunity to intervene militarily in Italy in 535. Sicily fell first; the civil administration there was directly subordinated to Constantinople.

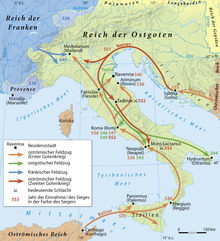

Italy was conquered between 535 and 553 in bloody battles by Eastern Roman troops led by the generals Belisarius and Narses ( Gothic War ). Emperor Justinian wanted to renew the Roman Empire ( Renovatio imperii ), but the fighting led to the impoverishment of large areas. In 554 the administration of Italy was reorganized and most of the senatorial offices were abolished; but the office of city prefect remained untouched. Italy finally became formally part of the Eastern Roman Empire in 554 , and in 562 the last Gothic fortresses also fell. But the Lombards invaded Italy as early as 568 and conquered large parts of the country. This event is generally considered to be the end of ancient times in Italy, whose state unity has now collapsed for 1300 years. The Lombard dominion in northern Italy soon split up into many smaller duchies (ducats). The remainder controlled by Constantinople was combined under Emperor Maurikios around 585 in the Exarchate of Ravenna . In addition to the area between Rome and Ravenna, large parts of the south as well as Liguria and the coast of Veneto and Istria remained Eastern Roman-Byzantine, with Liguria being lost to the Lombards in the 7th century.

Under Pope Gregory I , Sardinia , which was occupied by Ostrom in 534, was catholicized from 599 through the use of force. In 710 Arab troops occupied Sardinia, which had belonged to the province of Africa , but the inhabitants drove out the occupiers in 778 and repelled their last attack in 821. Four judiciaries , independent political units led by judges, emerged on the island , the last of which, the Arborea judiciary , lasted until 1478. As in the rest of Italy, the coastal towns were often abandoned.

The Gothic War, the harsh fiscalism of the imperial administration as well as the invasion of the Lombards from 568, the breakdown of trade relations and increasing insecurity led to a drastic decline in the population, an extensive disappearance of the old senate aristocracy, a shrinking of the cities, the regionalization of agglomerations and an increased agrarianization of the economy with an increase in subsistence farming. The Mediterranean area also changed its function as a trading hub, especially since the south side was conquered by Muslim armies from the 630s onwards, which also conquered Africa , the breadbasket of Italy, up to 700 and from there began to plunder the Italian coastal towns.

Lombards and Byzantines (568–774)

The entire class of the haves was integrated into the military system in the exarchate, and local militia troops strengthened the Byzantine army. This created a military-political hierarchy of regionally different independence. Around Rome it tied itself more closely to the local bishop, around Ravenna to the exarch, in Veneto to the family structures, tribunes and duces that arose there, and in the south to the apparatuses that were more closely tied to Byzantium. Emperor Konstans II. Moved with an army from Constantinople to Italy in 662 to fight against the Lombards and Arabs; he resided in Syracuse, Sicily, until his murder in 668, but could not achieve any lasting success.

The Lombards were not under joint leadership from 574 to 584, but the overarching coordination in the fight against the Franks made the re-establishment of a kingdom necessary. In opposition to Byzantine Ravenna, the Lombards chose Pavia as their capital, with central functions from the early 7th century. In addition, royal palaces were built in Verona (after 580), in Milan and finally in Ravenna. In contrast to the Frankish empire, the kings ruled from residences, especially the Palacium in Pavia, which had been a kind of capital since Rothari , and did not travel through their empire, as was the case north of the Alps for a long time, because its royal power was tied to his physical presence ( Travel royalty ). In contrast to the Frankish empire, there was also no merging of the Roman ruling classes with the Germanic ones, because as Arians they were remote from the Catholic population and acts of violence in the early phase of conquest drove many noble families, especially the senatorial nobility, into Byzantine territory. Around 600, however, the moderating influence of Queen Theudelinde , the daughter of the Bavarian Duke Garibald I. After that, Arian and Catholic kings took turns. King Rothari had the legal customs of the Lombards codified in 643 . Meanwhile, the Lombard dukes of Benevento and Spoleto managed to maintain a high degree of autonomy.

King Liutprand (712-744) managed to unite the Lombards and he took up the fight against Byzantium again. In doing so, he benefited from the fact that the Lombards were now Catholic and therefore more easily connected with the ruling Roman families in order to form a common ruling class. King Aistulf's edict of 750 no longer differentiated according to ethnic or religious background, but divided the population into different military categories according to their wealth and equipment. In 751 he succeeded in conquering Ravenna.

Allied with Pope Stephan II , Pippin , King of the Franks since 751, moved before Pavia in 756 and forced Aistulf to recognize his sovereignty and to cede the exarchate of Ravenna, which Pippin gave to the Pope ( Pippin donation ) and took over the patriciate of the city Rome. Between the Longobard Empire and southern Italy, the creation of a secular area of rule by the Pope (Patrimonium Petri) had come to a provisional conclusion, since Constantinople had only been able to intervene occasionally in the west since around 650 due to the threat from the Avars and Arabs .

Part of the Franconian Empire, "National Kings" (774–951)

From the year 774, Pippin's son and successor, Charles I , conquered the Longobard Empire and crowned himself in Pavia with the Longobard crown as "King of the Franks and Longobards". In the course of the Carolingian divisions, (Northern) Italy became an independent kingdom again, initially under Carolingian kings, from 888 under local kings of Franconian origin such as Hugo von Vienne and Berengar von Ivrea (" national kings ").

Frankish conquest

In the early Middle Ages Italy remained politically divided, and there were always fighting. The Lombards had conquered Ravenna in 751 and forbade all trade with Byzantine subjects since around 750. Because of the Lombard threat, the Pope called on the Franks for help. King Pippin conquered Ravenna, which, however, was now claimed by the Pope. There were similar disputes with King Desiderius , so that Pippin's son and successor Charles I attacked the Longobard capital Pavia in 774 and conquered the Longobard Empire. Charles transferred the former Byzantine territories to the Pope and thus came into conflict with Constantinople. With his coronation as emperor in 800 by the pope, there was a rupture between the empires that lasted until 812 ( two emperor problem ). The Ducat Spoleto was incorporated into the Frankish Empire, but not the Ducat Benevento . The nobility developed there in a similar way to that of the Franks, but the ducat split into the principalities of Benevento and Salerno and the county of Capua.

Karl divided Italy into counties and brands and brought Franconian nobles into the country as rulers. He granted the monasteries and dioceses privileges and equipped them with manors. The Lombard freemen were accepted into the Frankish army as Arimanni . They received greater influence, especially in the dioceses, and were of the same rank as the Frankish feudal nobility. At the same time there are indications from 845 on that the Lombard language disappeared. Nevertheless, the awareness of different origins was not lost, which was reflected in the name Lombardy for the Lombard core area and Romagna for the Roman-Byzantine. Thanks to the Carolingian Renaissance , there was a temporary increase in education, writing and art with recourse to Roman tradition.

Regnum Italicum, external attacks

After the death of Louis the Pious (840), the Frankish Empire was divided and the Regnum Italicum received a higher degree of autonomy with the capital Pavia . Ludwig II (844–875) stayed there at least once a year on his travels through the empire and called a meeting of all the greats. Around the capital, two to three days' journey away, there were royal palaces where documents were also issued. From January to April, the farm mostly overwintered in Mantua , which had been added to the small circle of residential cities since the early Carolingian times. Most of the time the court traveled to the Po valley, only rarely to Tuscany or even to Spoleto . Such trips were combined with a visit to Rome. When Ludwig stayed south of Rome between 866 and 872, this in no way diminished his authority in the north. The main task of the king was to maintain the social order as it was handed down and, above all, to administer justice. This was done by the king or his missi in front of as many witnesses as possible, with occasional greats being punished for wrongdoing against subordinates. But everyone had their position in the social hierarchy, which has always been understood as existing. The free in freedom, the servant in bondage: "liber in libertate, servus iin servitute", as it is called in a document of the Nonantola monastery from the year 852. From Berengar I, the judges (scabini) introduced by Charlemagne disappeared, and their influence on the royal or Paveser judges had long since declined. This escalation to Pavia and the legal education there was supposed to give Italy a completely different course in terms of the role of legal experts in urban development. In contrast to the scabini , they were not dependent on local masters, but on the king, but they mostly stayed away from the court. They were more closely involved in local disputes, at the same time a more complicated legal process developed, which now managed without the testimony of the pauperes (the poor). Also, the judges now almost exclusively dealt with disputes within the local elites, no longer those within the rest of the rural world. The exemption from judicial and thus royal interventions in entire rulership areas led in turn to greater internal independence, which was supposed to compensate for a fixed system of taxes and benefits vis-à-vis the king. At the same time, the lower social groups were excluded from the possibility of calling on the royal authority directly.

Ludwig II led an independent foreign policy, especially in the south, especially towards the Arabs under the Aghlabids , who began to conquer Sicily in 827 and soon established themselves in southern Italy. They managed to conquer the island by 902, the political center now shifted from Syracuse to Palermo . From 843 to 871 there was an Arab emirate in Bari , but its troops were defeated by Ludwig II. After that, Byzantium again took possession of Apulia and even regained influence in Benevento. The now independent Ducat Naples split up into the city rulers of Naples , Amalfi and Gaeta .

From 899 Hungarians in the north invaded Italy from the northeast. They had only been resident in the territory of their present state since 896. From there they traveled to Italy so often that the route they rode was soon called strata Hungarorum . Not only did they come to plunder, they were also used in the dynastic conflicts. In 922 they marched as far as Apulia, in 924 they set fire to the city of Pavia and the royal palace under the leadership of a salard and (possibly) as an ally of Berengar; Bishop John III also came. about life. Only after heavy defeats and with their Christianization ended their war campaigns after 955, which had covered almost all of Central and Southern Europe. In Italy the invasion of the Hungarians is considered the last invasion of the “barbarians” and thus the end of the great migration .

Feudalization, first urban independence

In the north, the territorial lords of powerful families emerged from the Franconian large units (see: Italian nobility ) . In addition, the dioceses gained considerable regional power and new priorities arose in the course of the Incastellamento . The Franconian greats, in turn, brought their allies from Burgundy and other parts of the empire into the battle for supremacy. Wido of Spoleto and Berengar I of Friuli fought for them , Hugo of Arles and Vienne became king from 926 to 941. Otto I finally challenged Berengar II of Ivrea for the royal dignity.

In addition to the feudal rule, the first urban dominions arose in the northern half, such as Rome, which was ruled by the family of Senator Theophylact , and Venice , which was still formally under Byzantium, but led an independent foreign policy under changing Doge families with their permanent seat established in 811. In the Pactum Lotharii , Emperor Lothar I granted Venice extensive trading rights in northern Italy, and his successors recognized Venice's property on imperial territory. At the same time, the cities of the lagoon had to fight off several invasions by Frankish, Slavic (around 846), Arab (875) and Hungarian (899 to 900) armies.

Church organization

The conquests of the Longobards also changed the hierarchy of the church communities. The capital Pavia subordinated itself to Rome and broke away from Milan. The seat of the diocese of Aquileia was moved to Grado , the diocese of Altinum was relocated to the less endangered island of Torcello in the Venetian lagoon .

Major changes in the diocesan borders were only enforced by the Carolingians in the 9th century, who with their reorganization created structures that were more similar to the Roman ones than the previously ruling Lombardy. The Franconian counts , who replaced the Gastalden and dukes , often resided in the diocese towns, but the bishops had to strive for lordly privileges and regalia that secured their comitatus . In many cases, episcopal territory emerged within the counties on the basis of various rights. The external attacks and the relative weakness of the Regnum Italicum contributed significantly to this independence . The bishops were mostly members of the ruling families themselves and were able to secure a following by donating income from the churches, chapels and baptismal churches (Pieven). However, several developments stood in the way of their direct exercise of power. The Carolingian laws gave the Pieven the right to collect tithes, and through the allocation of the rural population they received a kind of territorial rule - a specific feature of Italy. In addition, clerical dynasties from lay families emerged in some areas , which largely deprived the diocese of its rights. In addition, new secular rulers emerged from the bishops' followers in the cities.

From 816, the Constitutiones Aquisgranenses introduced a new element in communal development. A cathedral chapter was created with them , as it was demanded that the clergy should live together according to the monastic model. This clergy , in turn, tried to maintain control over a larger part of the episcopal patrimony . This phenomenon was even more evident in the private churches established by wealthy aristocratic families. The cathedral church and its patrimony were still subordinate to the bishop, but the cathedral chapters now took over the administration of the cathedral. The bishop was limited to his patrimony.

Rome emerged strengthened from the theological disputes with Byzantium in Italy and was considered to be the guarantor of the orthodox doctrine of the Trinity and its Christology . In addition, since Gregory I succeeded in converting the remaining Arians and the last pagans - in Sardinia also by force. A hierarchy of offices was established in Rome, which secured the necessary rights and income. Thus Rome became another important concentration of power in Italy, alongside the Franconian Empire and Byzantium as well as the Aghlabids and the calbites that followed them in Sicily.

In the iconoclasm , Emperor Leo III withdrew . 732/33 the Pope gave the patrimony of Calabria (Bruttium) and Sicily. Otranto rose to the seat of a metropolitan in 986 , with Squillace , Rossano and Santa Severina new bishoprics emerged. The southern churches were organizationally and culturally strongly influenced by Byzantium, which gave the area a Greek character that still exists today.

Imperial Italy (from 951)

In 951 Otto I gained control of northern and parts of central Italy through his marriage to Adelheid, the widow of Hugo I, and established the connection between imperial Italy and the empire . Venice , on the other hand , was not part of the Lombard Empire and the later Holy Roman Empire , which initially only consisted of the lagoon there , but was nevertheless an influential power that spread over the east and central northern Italy from the 14th century, especially in 1405 spread.

Under the Ottonians , their imperial church policy in Italy was continued and the dioceses were strengthened. With this, however, power was severely fragmented, even if the landed nobility were partially reconnected to the empire. The conflict with Byzantium in southern Italy was settled through the marriage of Otto II with Theophanu , but he suffered a heavy defeat against the Saracens at Cape Colonna in 982 . His son Otto III. who succeeded him in office in 983, Rome intended to make the site of the imperial coronations the capital of his empire. In 991 he made Gerbert von Aurillac Lord of the Imperial Church as Pope Silvester II , but the Emperor died in 1002.

Numerous Italian campaigns followed in order to secure rule in imperial Italy. They were connected with the coronation of the emperor by the Pope and were often referred to as the "Rome trip". It was usually preceded by the coronation as King of Italy with the Iron Crown of the Lombards. An “Italian” department of the Reich Chancellery was responsible for issuing documents; The Arch Chancellor assumed political responsibility for Italy , an office that from 965 lay with the Archbishop of Cologne.

Byzantines (up to 1071), Arabs (827-1091)

Southern Italy remained partially Byzantine or Lombard (principalities of Benevento , Capua , Salerno ) until the 11th century . Towards the end of the 11th century, these Lombard princes recruited Norman mercenaries to defend themselves against the Arabs , who ruled Sicily or parts of it from around 827 to 1091 and who ruled around Bari from 847 to 871 , and they then recruited all of southern Italy, including their principalities Clients conquered and founded the Kingdom of Sicily in 1130 in what was once Lombard, Arab and Byzantine territory .

Muslim fleets attacked Syracuse as early as 668 and 703 , but the Arabs failed to establish themselves permanently on the island. In 827, however, Admiral Euphemios defeated the Byzantine governor of Sicily to avoid his arrest and declared himself emperor. He called on the Aghlabids , who had become independent in Tunisia since 800 , and landed at Lilybaeum ( Marsala ) under the leadership of Asad ibn al-Furāt . After protracted fighting, Palermo fell in 831, 841–880 Taranto was Arabic, until 871 they stayed in Bari . There was an attack on Rome in 846 (which led to the walling of St. Peter's Church ) and in 875 on Venice and Aquileia . On Sicily, Cefalù fell in 857, Enna 859, finally Syracuse in 878 and Taormina 902. Around 880 to 915 the Arabs settled in Agropoli north of Naples , and in 900 they destroyed Reggio in Calabria. Rometta lasted until 965, Byzantium managed to occupy Taormina from 965 to 983. In 849 a papal Campanian fleet succeeded in defeating a Saracen fleet off Ostia . In 871 Ludwig II, Byzantium and Venice, supported by troops of Lothar II, Croatian and Dalmatian auxiliaries, advanced in southern Italy and retook Bari. The emir fled to Adelchin of Benevento. The Aghlabids responded with an attack of allegedly 20,000 men on Calabria and Campania, but they were subject to Ludwig's troops in 873 in Capua. In 876 Bari submitted to Byzantium, who succeeded in conquering Taranto in 880. Nevertheless, the power of expansion of the southern Italian-Tunisian Muslims only flagged from 915.

The Arabs were not only active as conquerors and plunderers, often in the service of the southern Italian greats. They also brought new irrigation techniques and crops with them. Lemons and oranges, dates, but also cotton, pistachios and melons as well as silk became important products on the island, whose main markets were now in the south. Palermo replaced Syracuse as the largest city in Sicily. The successors of the Aghlabids, the Fatimids , installed Hassan al-Kalbi as emir in Sicily in 948 , who founded the Kalbite dynasty. Otto II lost to them in 982 in Calabria. When there were disputes within the dynasty around 1030, Byzantium tried to use this opportunity to recapture. General Georgios Maniakes occupied Messina in 1038 and Syracuse in 1040, but the Byzantines had to withdraw again in 1043.

In 1063 a Pisan fleet attacked Sicily, but only the Normans succeeded in conquering the island in a tough battle from 1061 to 1091 - Catania fell in 1071, Palermo in 1072. They had already subjugated the Lombard territories and also expelled the Byzantines, whose last city Bari fell in 1071. Before the end of the conquest, the Normans turned to the heartland of Byzantium, which they tried to conquer from 1081. Byzantium was faced with a simultaneous attack by the Normans in the west and the Turkish Seljuks in the east. In this situation, Venice supported Emperor Alexios I with his navy and in return received trade privileges that exempted its traders from all taxes from 1082 onwards.

Economy, trade, credit and market quota in the high Middle Ages

Around 1000 there was an intensification of trade and an increase in production. This was due to an improvement in climatic conditions, a decline in epidemics such as malaria , but also to the decline in invasions from the east (Slavs, Hungarians) and the south (Arabs, Berbers). The population of Italy, which rose again, is estimated to be 2.5 million by 650 and 5 million by the late 11th century. By the end of the 14th century it was around 10 million.

This increase in population caused or enabled increased internal colonization , which reached its peak during the 12th century. The villication system largely dissolved, the (re-) introduction of citrus fruits, olives, cotton and silk production with only minor technological changes led to an intensification of the exchange. Cities in southern Italy, such as Amalfi , then Salerno , Gaeta , Bari , and the cities of Sicily benefited from the economic lead of the Muslim empires and the Byzantine Empire . They traded wood, slaves , iron, and copper throughout the Mediterranean , for which they bought spices, wine, luxury goods, dyes, ivory and works of art.

In the 10th century, Venice, thanks to its close ties to Byzantium and the Muslim empires, succeeded in not only becoming a trading but also a maritime power. Genoa and Pisa, on the other hand, faced considerably stronger opposing forces in the Tyrrhenian Sea , but were able to gain the upper hand within a century around 1100. These three soon-to-be-dominant maritime powers benefited from technical innovations such as the compass and portolan , but also the enlargement of the cargo space, the improved training of the merchant's sons and the state protection of trade convoys. They also extended trading hours and shortened the winter breaks.

The dominance over large parts of the Mediterranean made the northern Italian fleets a given means of transport for pilgrims and crusaders, which in turn produced enormous fortunes. Ultimately, the Genoese and Venetians succeeded in largely eliminating Byzantine competition and dominating trade to Constantinople and deep into Asia, thanks to privileges granted mainly under external constraints . Both Genoa and Venice initially conquered a chain of bases far to the east, which they expanded into real colonial empires. In addition, they maintained merchant colonies in numerous cities, which received varying degrees of autonomy.

This trading system in the east had to be countered by a corresponding system in the west and north in order to acquire goods and develop sufficient sales markets. This was true on the one hand for Italy itself, whose growing population was supplied with goods through a large number of trade fairs and the expansion of local markets, on the other hand for Western Europe, where Italian merchant colonies developed. They sat in the cities of Provence , Catalonia and Castile , the Rhineland, Flanders and England . Analogous to the Eastern merchants, they formed the switching stations for trade, for information and even for training the next generation. They were also the ones who met the luxury needs of the courts, including those of the Pope.

This rise in connection with the commercial revolution was able to build on the urban continuity, which was greater here than in most other areas of the former Roman Empire, in addition to the favorable spatial location of Italy and the contacts with economically more developed neighbors. The cities were the official seats of bishops and abbots, of royal administrative bodies, whose economic bases were nevertheless predominantly in the countryside, and the cities had markets and fairs, ports and long-distance trade routes and profited from the need for luxury. In addition, they were able to make themselves largely independent of the sovereigns in the north and force the landed gentry to move into the city. With these developments, the dominance of the agricultural over the urban in Italy collapsed. Trade, monetary affairs and commercial enterprise under the aegis of an emerging bourgeois ruling class shaped the country. The urban population is believed to have increased five or six fold between the 11th and early 14th centuries. This growth was largely due to the influx from the countryside, so that alongside the economic revolution, there was a city revolution . On the one hand, this influx caused a massive expansion of the cities, and on the other hand, the emergence of a construction industry that became one of the most important branches of the economy.

The municipal leadership groups consisted of long-distance traders, real estate owners and landowners. They were urged to invest their capital in trade trips and shipbuilding, but also in state welfare tasks, such as the supply of grain and bread, the massive turnover of which played a major role in the creation of large fortunes. The goods on board the ships also mostly belonged to one or more investors who were linked to the skipper by a contract. Business such as banking and exchange companies were soon added to trading and looting . This applied both to the small, local credit market and to long-distance trade credits, which in Venice were more publicly organized and in Genoa more privately organized. From the 12th and 13th centuries, the traders joined together to form companies (compagnie) that emerged from family associations and formed branches. In Venice, brothers were even automatically considered to be members of the same trading company.

The techniques of transferring money and lending were noticeably improved from the 12th century onwards. Much earlier than in the rest of Europe, the risks of coin transfer and the hurdles of changing from one coin system to another were overcome and, at the same time , an extensive credit system based on bills of exchange was developed through hidden interest payments, which were forbidden due to biblical prohibitions . Based on Roman law , maritime and commercial law was also expanded.

By 1250 the commercial revolution had taken hold to the point that it dominated the essence of the Italian metropolises. The mentality of the management layers was based on spatial expansion, such as to Russia , China , India and Africa, but also Norway and the Baltic Sea region, in Italy itself the turnover of goods expanded on the basis of increasing money and market mediation of most economic transactions. In order to pave the way for the greatly increased volume of trade, the waterways that were naturally available were expanded by building canals and improving the roads. The vast majority of the trade, especially that of bulk goods, continued to be done on the water.

Commerce and industry formed a unity that was difficult to define in the cities. The craft guilds (arti) mostly related to the shop (bottega) and only rarely took on "industrial" dimensions. The situation was completely different in mining and shipbuilding as well as in the textile sector. Up to the 12th century Calabria and Sicily were the centers of silk production, from the 13th century also Tuscany and Emilia, there again Lucca and Bologna . Initially, the Italian cloth merchants were mainly active in the intermediate trade between Brabant - Flanders and northern France, but they began to develop a mixture of craft, wage and home work in a kind of publishing system (opificio disseminato) .

Italy's mediating role forced a double coin system of silver and gold coins, which initially operated the southern Italian cities on a small scale as the successor to the Muslim ones, whose tari they took over. In the middle of the 13th century, Florence and Genoa, and at the end of the century also Venice, switched to a double system of gold and silver coins, which brought the cities considerable income and at the same time made it possible to manipulate prices and shift social burdens. So Florence installed a domestic currency and a currency for foreign trade that was kept stable. This made it possible to reduce wages compared to the income from foreign trade without endangering social peace at home.

Around 1200, especially after the sack of Constantinople (1204) in the course of the Fourth Crusade , the supply of capital exceeded the corresponding market. This gave new opportunities to moneylending and banking, with some of the banks specializing in high finance businesses . They financed royal courts and organized the papal finances. Wars were also increasingly being pre-financed by them. The risk, however, was that there was no minimum coverage of the issued capital and, above all, that there was little opportunity for foreign borrowers to force them to repay.

In contrast, the development in southern Italy was completely different. The cities there were on the threshold of a commercial revolution in the 11th century, but after the expulsion of the Byzantines and Berbers, Norman rule brought pronounced feudalization under the dominance of the newly raised nobility. Its latifundia and the peasants' continuing ties to the plaice prevented the development of agricultural diversity, especially since wheat, as an export good that was used to finance war, took up ever larger areas. Both Normans and Staufer, Anjou and the Spanish rulers used this wealth to finance their court rulings and their battles among themselves and their attempts to expand against Byzantium. At the same time, the municipalities were subjected to rigorous tax administration and fiscalism adapted to fluctuating financial needs, and municipal self-organization was largely suppressed. Craftsmen and traders' corporations also played only a minor role.

This led to the fact that the Italian north viewed the south as a raw material country - such as wine, oil, cheese, wood, salt, cattle, seafood, etc. - and deepened the conditions created by the domestic dynasties. The merchants from Genoa, Florence, Pisa and Venice settled in large numbers in the port cities in the 12th century. After the end of the Hohenstaufen dynasty (1268), the Florentines dominated the empire of the Anjou, the Pisans dominated the Aragonese Sicily. They were joined by Catalan merchants in the 14th century, who also contributed to the fact that the capital flowed out and hardly any investments were made in the country.

All efforts of the Hohenstaufen, for example to promote mining, sugar production, handicrafts and trade, to expand the Anjou's road network, and even the establishment of new trade fairs and markets brought hardly any improvements in view of this basic constellation. However, these state control attempts benefited the port cities, as they profited greatly from exports. Naples became important again as the capital for shipbuilding and as a center for luxury goods. After the unification of Naples with Sicily (1442), trade with the Spaniards intensified immensely, but here, too, southern Italy tended to play the role of supplier of raw materials. Silkworm farming took off in Calabria, merino sheep were imported, tuna and corals were increasingly exported.

Attempts at reform by the church and society

In the north, the increasing urbanization was accompanied by power struggles between the land-based captains and the Valvassors , who were more like the towns and who held fiefs and enjoyed imperial rights. At the same time, city lords and local communities fought for supremacy. The Milan Pataria of 1057 also caused the reform papacy , which, like the rebels, fought against simony and Nicolaitism , came into conflict with imperial rule. This was mainly due to the fact that Pope Gregory VII claimed the right to appoint the Milanese bishop, and finally from 1075 that of all bishops. As early as 1024, the Cives Pavias destroyed the royal palace, thereby ending its role as a royal residence. From the 1080s onwards, consular constitutions in the cities became tangible, from 1093 onwards, formal alliances between cities.

In Italy in the 11th century, reform efforts of the church were combined with efforts to reduce dependence on transalpine kingship. In the northern dioceses in particular, the imperial church system had created a strong dependency of the churches, which was also reflected in the fact that Bavarian bishops in particular resided there, such as in Aquileia, in the march of Verona and in Ravenna. In other cities, the bishops often came from the group of feudal Italian captains, and from the 12th century also from the Valvassors. Although the bishops retained a certain degree of independence, they were increasingly integrated into the ruling system of the empire, which was organized on the basis of the manorial system. There was increasing resistance to the submission of bishops to the will of a lay royal. The uprising of Pataria of 1057, which was primarily aimed at the moral restoration of the church, continued to have an effect after its suppression. In 1067 the cardinal legates in Milan confirmed to the bishop the spiritual power exercised out of his office over the entire clergy, the community of believers and in particular over the baptismal churches, regardless of whether the associated benefits were due to laypeople or clergy. In 1075 Pope Gregory VII explicitly forbade the appointment of clergy by lay people to their offices. Up until the Worms Concordat (1122), there was an initial phase of dispute with the German rulers.

The spiritual and social dimensions of the reform movement should not be underestimated in view of the underlying economic and power interests. Around 1034, with the heretics of Monforte in Piedmont, heterodox movements appeared for the first time , groups whose teaching the church leadership considered incompatible with their dogmas. In addition to the Pataria (1057) already mentioned, above all Arnold von Brescia (1155), the Cathars , the Humiliates , the Italian Waldensians or the Passengers should be mentioned, but also Ugo Speroni († after 1198), who opposed hierarchy, Applied priesthood and sacraments.

Initially, reform-minded hermits, such as Petrus Damiani , who wanted to strengthen the life of the clergy in communities, often acted on the edge of the accepted spectrum . Canonical pens, initiated by clerics and laypeople, sprang up everywhere . In the monastic sector, the Virginians , the Order of Pulsano, the Wilhelmites , the Carthusians , the Cistercians and the Floriacians were created by Joachim von Fiore . Against the diversity of movements inclined towards the world, a movement emerged that turned away from the world, practiced contemplation and penance and thus revived Benedictine traditions more strongly. This is how the Congregations of the Coelestines and the Silvestrians came into being .

Lay movements like the Alleluia Movement were equally influential; some of them were antiheretic. In the 13th century the flagellant movement arose, to which the third order of the Franciscans long leaned. Finally, Franciscans and Dominicans were added , and later also Carmelites , Augustinian hermits , Servites and sack brothers . The Pope used the first two in particular in his propaganda struggle against the emperor.

In the 14th and 15th centuries, numerous congregations turned to charitable work, as beguines and begarians had done earlier. The result was an extremely dense network of hospitals and brotherhoods, many of which were in municipal hands or were brought into being by the cities. That the representatives of these movements were by no means satisfied with this is shown by men and women such as Bernardine of Siena , Catherine of Genoa or Franziska of Rome , who gave mysticism new impulses, but above all Girolamo Savonarola , who carried out his ideas from 1494 to 1498 seized political power in Florence.

Italy was largely spared from the persecution of witches. They did exist in the Alpine valleys (the most severe persecutions took place in Valcamonica from 1518 to 1521 and in Como until at least 1525 ), but Andrea Alciati (1492–1550), leading commentator on the Codex Iuris Civilis , wrote reports on the occasion of the persecutions there , in which he spoke of “nova holocausta” with a sharpness that could hardly be surpassed. He accused the Inquisition of creating the phenomenon of witchcraft instead of fighting it, as they claimed. The Franciscan Samuel de Cassini from Milan had already opposed the persecutions in 1505, but they occurred occasionally until after 1700.

The Inquisition was founded by Rome in disputes with the numerous social and religious movements and was based primarily on the Dominicans. The Waldensians, the "poor of Lyon", were in 1184 in the Pope Lucius III. written Edict Ad Abolendam listed as a heretic . Another conviction followed in 1215 under Pope Innocent III. In 1252 the Waldensians were condemned again along with other groups in the bull Ad Extirpanda written by Pope Innocent IV . From the 1230 / 1240s, the persecution started from the Inquisition. While the Inquisition eradicated the Waldensian creed in Calabria and Provence, it survived in some valleys of the Cottian Alps .

Pope, Normans, Staufers (until 1268)

In the high and late Middle Ages, large parts of central Italy were dominated by the Roman Catholic Church and, like northern Italy, were directly affected by the power struggles between the emperor and the pope (beginning with the investiture dispute and ending in the 14th century) and by the battles between the municipalities . The latter usually assigned themselves to the main contending parties as Ghibellines and Guelphs . In addition, there were often strong tensions within the municipalities.

The end of Arab and Byzantine rule in the south played a significant role in this. In 1038 and 1040, Byzantium managed to recapture Messina and Syracuse , but disputes at court and the spread of the Normans brought into the country as mercenaries led to the collapse of both Byzantine and Arab rule.

Henry II intervened in the south in 1021; the southern Italian princes submitted to him and he besieged the Byzantine Troy in Apulia. The papacy, which until 1012 was dependent on the Crescenti , now depended on the Tusculans . However, his son and successor made several long-term decisions with far greater consequences: With the appointment of Suidger von Bamberg as Pope Clement II , Heinrich III. 1046 the requirements for the reform papacy. He also enfeoffed the Norman Rainulf II in 1047 with the county of Aversa and Drogo von Hauteville with his Apulian land that was on Byzantine territory. This was the first time that Norman leaders entered into a feudal bond with the empire. The Pope, in turn, enfeoffed Robert Guiskard in 1059 with Apulia, Calabria and Sicily, which was still to be conquered. Under his leadership, the Normans then conquered Sicily in a kind of crusade from 1061 to 1091

Another important factor was the enforcement of feudal law in northern Italy, in which the emperor stood up in favor of the Valvassors ( Constitutio de feudis , 1037), in order to assert the power of the greats who had become independent in Italy, which the emperors rarely visited Counterbalance. In order to further limit the power of the great , he endowed several cities with privileges. Accordingly, one of the most powerful Capitans, Gottfried the Bearded of Tuscia , became the protector of the reform popes. This was all the more important as the Normans were unreliable allies; so they marched in 1066 into the patrimony of Petri , and despite the ban on him, Robert Guiskard occupied the principality of Salerno (1076), the last Lombard rule. This extremely threatening situation for Pope Gregory VII may have caused his comparatively mild behavior towards Henry IV during his penance to Canossa .

The Pope recognized all conquests of the Normans in 1080 and released Robert Guiskard from the spell. Robert now took a massive stand against Henry IV and freed the Pope from captivity. In addition, the Normans ensured a slow re-Catholicization - in Santa Severina the Orthodox rite was retained until the 13th century - of the once Byzantine dioceses and the establishment of new episcopates. Gallipoli kept the Byzantine rite until 1513, Bova even until 1573 (a Greek dialect still exists there today). In Sicily, the dioceses that had been abolished by the Muslims were re-established. In addition, Robert made preparations to conquer Byzantium , which had been weakened by the conquests of the Seljuks . With this, in turn, he made an enemy of Venice, which no longer tolerated the establishment of power on both sides of the Adriatic in the interests of the freedom of its trade routes.

The Hohenstaufen now laid claim to the Mathildic estates and courted Milan, which had started to create its own territory with the subjugation of Lodi (1111) and Como (1127).

The schism of 1130 - in Rome the families of the Pierleoni and the Frangipani fought each other - which was only ended by the Second Lateran Council in 1139 , on the other hand, weakened the papal side, which was now forced to grant the Normans numerous rights. Lothar III. sought at the request of insurgents to fight Roger II, who had been crowned king since 1130, from 1136 to 1137. Roger was defeated in the Battle of Nocera (July 24, 1132) against the rebels under Rainulf von Alife. Lothar now pulled Milan on his side. As a result, Milan's enemies, especially Pavia and Cremona , almost automatically became his opponents. Pisa, Venice and Genoa in turn supported Lothar in the conquest of Bari . But the army refused to pursue Roger to Sicily, so that by 1138 he succeeded not only in imprisoning Pope Innocent II , but also in regaining all rights in southern Italy after Roger's main adversary Rainulf had died in 1139. In 1143/44 the Pope was also in distress due to an uprising in Rome under Arnold von Brescia .

Conrad III. negotiated with the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I about an alliance against the Normans who had attacked Byzantium. In 1148 they decided on a joint campaign that should lead to the division of the Norman Empire. Roger allied himself with the French king and with the Guelphs . After the emperor's death, his successor Friedrich I pursued a similar policy, but he did not tolerate any Byzantine involvement. He also drew Welf VI. on his side by enfeoffing him with huge estates. In 1154 Roger II died.

The Norman Empire was now an important Mediterranean power (it conquered Tunis in 1146), especially since it now had considerable economic resources at its disposal. In 1155 and 1156 he succeeded in reaching an agreement with the Pope as well as with Genoa and Venice. However, it tried in vain to conquer the Byzantine Empire, and made a last attempt under Wilhelm II in 1185 , which also failed. The crusades had not only led to excessive looting, but also to an intensification of trade relations, especially between southern Italy and later also northern Italian with the entire Mediterranean region. The Norman Empire fought in Italy in alternating coalitions against imperial and papal claims, but was able to grow into the role of protector against the claims to power of the Roman-German emperors through its long-term change to the side of the Pope from 1155 until it was inherited by the Hohenstaufen in 1190 fell. These received the Norman Empire in 1194. Palermo was the capital and residence of Emperor Frederick II , who grew up in the south.

Despite the dynastic connection in the Staufer period, southern Italy was never formally part of the Holy Roman Empire and also represented a papal fiefdom. The popes feared that the Staufers would "embrace" the Papal States and fought against its dominance. In the dispute between Frederick II and the Popes, which his successors continued, the last two Staufers were defeated in 1266 and 1268 by Charles I of Anjou . In 1282 a popular uprising brought first Sicily ( Sicilian Vespers ), then an inheritance in 1442, the mainland southern Italy to Aragón (which became part of Spain from 1492 ).

Communes, signories, imperial politics (11th to 15th centuries)

Communal independence