History of Berlin

The history of the city of Berlin began in the High Middle Ages with the establishment of two trading centers. Berlin was first mentioned in a document in 1244, but neighboring Kölln was already mentioned in 1237. Both places are probably a few decades older.

In 1309, Kölln and Berlin formed a city union in order to guarantee mutual military and legal cooperation. In 1432 both places merged to form the twin cities of Cölln-Berlin, although the official unification to form the city of Berlin was not to take place until 1709. In 1486 Kölln-Berlin finally rose to the seat of the margraves and electors of Brandenburg from the House of Hohenzollern . Elector Joachim II introduced the Reformation in Berlin in 1539 . The accomplished in 1613 conversion of Elector Johann Sigismund and his court to the Calvinist faithled to long-lasting denominational tensions with the Lutheran population of Berlin.

The Thirty Years War (1618–1648) ended Berlin's cultural and economic boom as a royal seat. Epidemics and troop movements cut the population in half. Only under the Great Elector did the city gradually recover from the consequences of the war. The Great Elector had a fortress built around Berlin and Cölln and made it possible for French religious refugees to immigrate . Berlin experienced a representative structural upgrade, especially of the palace area , at the beginning of the 18th century as a result of the coronation of Frederick I. His successor Frederick William I promoted the building of churches, city palaces and town houses and created parade grounds. In the course of the 18th century Berlin outstripped all German cities except for the imperial city of Vienna in terms of population and size.

Frederick the Great lived in Potsdam , but drove the further expansion of Berlin on Unter den Linden with the Forum Fridericianum and the construction of representative immediate buildings and founded state-owned manufacturers such as the Königliche Porzellan-Manufaktur Berlin . Under his successor Friedrich Wilhelm II , the city underwent its first classical transformation. After two years of French occupation (1806–1808), Berlin developed in the course of the 19th century into one of the most populous metropolises in Europe, an industrial and scientific center and an important transport hub in the railway network. In 1871 the city advanced to become the capital of the German Empire .

Origin of name

The name Berlin is originally Slavic . It goes back to the old Polish Birlin, Berlin and means 'place in a swampy area'. It is based on Old Polish birl-, berl- 'swamp, morass', supplemented by the Slavic suffix -in, which characterizes the location . The documented tradition with the article ("der Berlin") speaks for an original field name that was taken up by the settlers.

The name Kölln is probably a name transfer from Cologne on the Rhine, which goes back to the Latin colonia , planting city in a conquered land, colony. However, a derivation from an Old Polish name * kol'no, which would result in kol 'stake', cannot be completely ruled out .

The city name can neither be traced back to the alleged founder of the city, Albrecht the Bear , who died in 1170, nor to the heraldic animal of Berlin . This is a talking coat of arms with which an attempt is made to depict the city name in a German interpretation (Berlin = 'bear'). The heraldic animal is therefore derived from the city name, not the other way around.

Prehistory (16000 BC to 1200 AD)

The end of the Vistula ice age

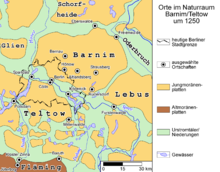

Finds of flint stones and worked bones suggest that the Berlin area was settled from around 60,000 BC. Close. At that time, large parts of northern and eastern Germany were covered by the glaciations of the last Ice Age , which lasted from about 110,000 to 8,000 BC. Lasted. In the Baruther glacial valley , around 75 kilometers south of Berlin, the inland ice reached its maximum southern extent around 20,000 years ago. The Berlin area, whose lowland is part of the young moraine land of the Vistula Glaciation, has been ice-free again for around 19,000 years . Around 18,000 years ago, the flowing meltwater formed the Berlin glacial valley as part of the Frankfurt season , which, like all glacial valleys underground, consists of mighty meltwater sands. The Spree used the glacial valley for its course, in the lower Spree valley a tundra formed in places . To the west, humid lowlands and moor areas dominated the appearance of the valley.

The Barnim and Teltow plateaus formed parallel to the later course of the Spree. As the ice receded, stationary game such as roe deer , deer , elk and wild boar became sedentary and displaced the reindeer . As a result, the people who made their living from hunting began to build permanent settlements. In the 9th millennium BC Chr. Settled on the River Spree, Dahme and Bäke hunters and fishermen , the arrowheads left, scrapers and flint hatchets. From the 7th millennium BC A mask comes from BC, which was probably used as a hunting spell .

Neolithic, Bronze and Iron Ages (4000 BC to 500 AD)

In the 4th millennium BC Cultures formed with agriculture and livestock , using handcrafted ceramics and storage facilities. Three burials in the Schmöckwitz area from this period are the oldest human finds on Berlin soil. A funnel cup culture village was excavated from 1932 to 1934 in the area of the Britz horseshoe settlement.

Most of the Neolithic finds come from the spherical amphora culture around 2000 BC. Around 200 Bronze Age sites attest to an increasingly dense settlement on the Havel and Spree. An estimated 1000 people are said to have spread over about 50 settlements at this time, most of which are attributed to the Lusatian culture and the Nordic Bronze Age . A Bronze Age village discovered in 1955 in Lichterfelde consisted of seven or eight rectangular houses grouped around a village square. The post houses were equipped with clay-clad walls and thatched or thatched roofs. Another village with almost 100 buildings was uncovered during the construction of the clinic in Berlin-Buch .

With the beginning of the Iron Age around 600 BC The Lausitzer was replaced by the Jastorf culture . Since about 500 BC The following Germanic tribes advanced into the Berlin area and settled on the wooded heights of the Barnim and the Teltow. Germanic settlements were excavated mainly in Rudow , Lübars , Marzahn and Kaulsdorf . In the period after the birth of Christ the Elbe German appeared Semnones , a tribe of the Swabians on. Part of the Semnonian population migrated to the southwest in 200 AD. They were followed by East Germanic Burgundies .

In the 4th and 5th centuries AD, large parts of the Germanic tribes left the area around the Havel and Spree and migrated towards the Upper Rhine to Swabia . The population density in the Berlin area therefore decreased, but it remained populated by residual Germanic groups.

Slavs and founding of the Mark Brandenburg (500–1200)

From the 6th century Slavic tribes came to the Lausitz area and at the end of the 7th century also to the largely depopulated Spree-Havel area. They settled in previously uninhabited areas. In the later city center of Berlin there are no Slavic traces. They can only be found on the plateaus of Teltow and Barnim as well as on the banks of the Spree and tributaries.

The tribes of the Heveller (Havelslawen) and the Sprewanen , who belonged to the Lutizen tribal association , settled in the area of Berlin . The Hevellers populated the Havelland up to the Rhinluch and the Tegeler See and had their headquarters on the Brennaburg on today's cathedral island of the city of Brandenburg . To secure their territory to the east, the Hevellers built another Slavic castle wall around 750 a little south of the mouth of the Spree ( Burgwallinsel ) in the Havel , around which a merchant settlement developed thanks to the favorable traffic situation. Further to the east and separated by a wide forest belt was the settlement area of the Sprewanen, the center of which was the Köpenick Castle Island at the confluence of the Spree and Dahme rivers. There was also a Slavic rampart here in the 9th century. Spandau and Köpenick were connected by an important trade route that ran south of the Spree, but was moved to the north bank around 1170.

The Sprewanen founded further settlements in the areas of Mahlsdorf , Kaulsdorf , Pankow and Treptow . The Sprewanen prince Jaxa von Köpenick , attested by numerous coin finds , who presumably had his headquarters at the Köpenick castle, was decisively beaten and expelled in 1157 by the Ascanian Albrecht the Bear (1134–1170) during the conquest of the Brennaburg. Albrecht, who was already in 1134 by Lothar III. was enfeoffed with the Nordmark , then founded the Mark Brandenburg and appointed himself its first margrave . The Spandau castle wall , which was abandoned during the 12th century, was moved as an early town by the Ascanians further north to the area of today's Spandau Citadel , and a new town center developed across from the Spree estuary.

The foundation of the first villages in the area of today's Berlin coincided with the subsequent land development of the Ascanian margraves in Teltow, which was characterized by a skilful settlement policy and a clever inclusion of the internationally active religious orders of the Cistercians ( Lehnin Monastery ) and the Knights Templar ( Komturhof Tempelhof ) .

Trading city in the Middle Ages (1200–1448)

Creation of the twin cities of Berlin-Kölln

At the end of the 12th century, long-distance merchants , who probably came from the Lower Rhine - Westphalian region and traveled through the area, established their first settlement on the Spree lowlands with the Kölln Spree island. At this point between the plateaus of the Teltow and the Barnim, the swampy glacial valley narrowed to four to five kilometers. Berlin emerged on the right, northern bank , on the Spree island directly opposite Kölln .

Recent excavations have shown that the first settlement activities for Berlin / Kölln began as early as the last quarter of the 12th century. Archaeological investigations 1997–1999 came across a beam in the Breiten Straße 28 (Alt-Kölln) which was reused around 1200 and which could be dated to "around / after 1171" with the help of tree ring analysis. In 2007 an oak beam was found in an earth cellar during excavations on the Kölln Petrikirchplatz , the analysis of which showed that the tree had been felled around the year 1212. In 1997 and 2008, settlement remains were found in the area of the palace square under the foundations of the Dominican monastery, which was demolished in 1747 . The most recent date is a remains of wood from 1198 ( edge of the forest ); the entire finding bears scorch marks. This part of the settlement was apparently abandoned after 1198 after it was destroyed by fire, because it was built over by the first Kölln city wall at the beginning of the second half of the 13th century at the latest. The dendro data determined since the political turning point in 1990 can only be used scientifically in different ways. The oldest "resilient" dendro date for Berlin / Kölln is 1198 (forest edge).

It is still unclear who is older: Berlin or Kölln, and who the respective founder was: a cooperative of long-distance merchants (the Berlin Nikolaikirche has the patronage of long-distance merchants) or the margrave (Kölln has the Brandenburg eagle in its coat of arms). The question of whether Kölln had a settlement of the Archbishops of Magdeburg as a predecessor (Rolf Barthel's Magdeburg hypothesis ) is also unanswered .

Berlin and Kölln emerged as the founding cities . In contrast to the Slavic foundations of Spandau and Köpenick (first mentioned in a document in 1197 and 1209/1210) at the western and eastern exit of the Spree Valley, which had more of a strategic importance, Berlin and Kölln were planned as trading centers from the outset in order to exploit the trade advantages ( Customs, defeat ) from Spandau and Köpenick.

The documents with the earliest mentions of Kölln from October 28, 1237 and Berlin from January 26, 1244 are in the Domstiftsarchiv in Brandenburg an der Havel ; the documents are related to a tax dispute between the margraves and bishops of Brandenburg, the settlement of which was an essential source of funding and probably also resulted in the granting of city rights (see Brandenburg tithe dispute ). It should be noted that the Brandenburg Treaty of October 28, 1237, the inter alia. a Symeon plebanus de Colonia ("Symeon, Pastor of Kölln") attests only in a document issued in Merseburg on February 28, 1238. In 1244 the same Symeon appears in another document as provost of Berlin, d. H. At that time Berlin was already the center of an archdeaconate . Berlin was first mentioned as a city ( civitas ) in 1251, Kölln only ten years later.

The development and the targeted privileging of the expansion of the twin town by the two margraves since the 1230s was closely related to the settlement of the Teltow and Barnim plateaus, as described in detail in the Märkische Fürstenchronik . The Ascanian settlements on the north-western Teltow were strategically secured against the Wettin rule on the Teltow with Mittenwalde and Köpenick as well as the very likely planned Wettin development of a rule around Hönow (including Hellersdorf ) by the Templar villages founded in the manner of a locking bar around the Komturhof Tempelhof . At that time, the border between the Ascanian march and the Wettin possessions ran in a north-south direction through the middle of what is now Berlin's urban area. The assertion of an intervening strip by the Archbishops of Magdeburg is largely disputed. The tensions with the Wettins were decided in the Teltow War between 1239 and 1245 in favor of the Ascanians, who finally brought them the entire Teltow and Barnim (apart from Rüdersdorf ) and thus the entire current city area.

- Sources and see in detail: Development of the Berlin area , background of the Teltow war

Berlin-Kölln owes a large part of its ascent from a small bridge to an important Spree crossing to the Ascani, who led the old long-distance trade route from Magdeburg to Posen , which also led via Spandau and Köpenick, through the city. Economically, it was able to stand out thanks to the joint ruling Margrave Otto III. and John I issued Niederlags- or staple rights prevail over the cities of Spandau and Köpenick. This obliged traveling merchants to offer their goods in the city for a few days. In addition, there were duty exemptions , which favored the intermediate trade and export of agricultural products. The trade connections reached from Eastern Europe to Hamburg , Flanders and England as well as to the Baltic Sea coast and to southern Germany ( Via Imperii ) . At that time, the city covered an area of 70 hectares and included the trading post at Molkenmarkt and around the Nikolaikirche as well as the area of the New Market and the Marienkirche . The most important connection between Berlin and Kölln was the Mühlendamm , which dammed the Spree and on which there were several mills.

Although Berlin and Kölln had many common facilities, both cities were run by separate administrations. The councils, which consisted of twelve or six members, included wholesalers and long-distance traders who made up the town's patriciate . At the head of both administrations stood the mayor , who was the representative of the margrave in Berlin and Kölln. Marsilius de Berlin is mentioned as the first known Schulze in 1247, after the city charter was granted at the latest in 1240; the latest state of research (Fritze 2000) assumes a connection with the tithe contract of 1237, as well as the upgrading of the Nikolaikirche to the provost church and the layout of the Marienviertel.

The middle class was made up of merchants, master craftsmen and farmers who organized themselves in guilds . The oldest document of the guild system to confirm a true bakers guild dating back to 1272. From 1284 is a first Guild letter for Schuster handed down, the clothier received 1,289 different rights and the butcher guild was founded 1311th These four most respected trades later formed the four trades .

At the time there was a provost's office at religious institutions , with the Marienkirche, the Nikolaikirche and the Petrikirche (Kölln) three parish churches , the gray monastery of the Franciscan order and the Dominican monastery in Kölln as well as the associated monastery churches. A separate district was created around the Heilig-Geist-Spital , the Georgenhospital was located in the east of Berlin in front of the Oderberger Tor or Georgentor . The Gertraudenhospital , founded in 1406, was located southeast of Kölln. In the monastery road to the House in which temporary residence of the electors was.

In 1307 Berlin and Kölln formed a union in order to pursue a common alliance and defense policy. A third town hall was built on the Long Bridge for the joint council .

Mark Brandenburg and Berlin-Kölln under the Wittelsbach family

After the Ascanians died out in 1320, the Roman-German King Ludwig IV , who came from the House of Wittelsbach and was an uncle of the last Ascanian Henry II , transferred the Mark Brandenburg to his eldest son Ludwig the Brandenburger in 1323 . From the beginning, the Wittelsbach government over Brandenburg was marked by strong tensions. In 1325 the citizens of Berlin and Cologne slew and burned Propst Nikolaus von Bernau , who was a supporter of Pope Johannes XXII. from France against the emperor, thereupon the Pope imposed the interdict on Berlin . As a result, there were further tensions with the Wittelsbach rule. In 1349, 36 Brandenburg towns paid homage to the “ False Woldemar ” in the Spandau citadel in the dispute over the Mark before the Wittelsbacher regained the upper hand.

At the end of 1351, Brandenburg went to Ludwig's half-brother Ludwig the Roman by contract . In 1356 he won the electoral dignity for the Mark Brandenburg through the Golden Bull . In the 14th century (since 1360) Berlin and Kölln were members of the Hanseatic League . Out of hatred of his Bavarian brothers, with whom he had got into a dispute over the cure and the Bavarian succession after the death of his nephew Meinhard, Ludwig the Roman concluded a hereditary brotherhood with Emperor Karl IV in 1363. This was to be named after his and his younger brother Otto's childless Death assures the Mark Brandenburg Karl's son Wenzel . Ludwig then had the estates pay homage to the emperor. When Ludwig died without leaving any children, his brother Otto was his successor. Like his first wife Kunigunde, Ludwig was buried in the Gray Monastery in Berlin.

Berlin-Kölln under the Luxemburgers and early Hohenzollern

In 1373, after a number of disputes between Otto and Karl and the Margraviate of Brandenburg, Berlin fell to the Luxembourgers through another treaty . In 1378 there was a major fire in Kölln and in 1380 also one in Berlin. Among other things, the town hall and almost all churches were destroyed, as well as the majority of the town charter and documents of the towns.

The Hohenzollern burgrave Friedrich I became elector of the Mark Brandenburg in 1415 and remained so until 1440. Members of the Hohenzollern family ruled Berlin until 1918, first as margraves and electors of Brandenburg, then as kings in and of Prussia and finally as German emperors . The residents of Berlin have not always welcomed this change. In 1448 they revolted against the construction of the new palace by Elector Friedrich II. Eisenzahn in “ Berlin indignation ” . However, this protest was unsuccessful and the population lost many of their political and economic freedoms.

Towards the end of the 14th century, which was shaped by the plague in Europe and thus also in Berlin , the population in the twin cities of Cölln-Berlin was severely decimated, so that the food supply for the remaining inhabitants, whose diet was previously mainly plant-based food existed, increased by an increased supply of meat.

Electoral residence city (1448–1701)

After 1448, Berlin-Kölln was increasingly viewed as the residence of the Brandenburg margraves and electors. In 1451 Friedrich II moved into his new residence in Kölln. When Berlin-Kölln became the residence of the Hohenzollern, it had to give up its status as a Hanseatic city (1442). The economic activities shifted from trading to the production of luxury goods for the court nobility. The population rose to over ten thousand in the 16th century. The city also wanted to participate in the lime mining in Rüdersdorf , which is why it bought the neighboring Woltersdorf in 1487. There was no limestone to be found there, but Berlin kept the village until 1859.

In 1510, 100 Jews were accused of stealing and desecrating hosts . 38 of them were burned, two were beheaded after they had converted to Christianity, and all other Berlin Jews were expelled. After their innocence could be proven after 30 years, Jews were allowed to settle back to Berlin - after paying a fee - but were expelled again in 1573, this time for a hundred years.

To the west of Berlin, the zoo was laid out in 1527 as a hunting ground for the electors and in 1573 a bridle path was built as a connection to the castle, which later became the street Unter den Linden . This began the direction of urban development towards the west.

Joachim II , Elector of Brandenburg and Duke of Prussia, introduced the Reformation in Brandenburg in 1539 and confiscated properties of the church as part of the secularization . He used the money he acquired for major projects such as the construction of the Spandau Citadel and the Kurfürstendamm as a connecting road between his hunting lodge in Grunewald and his residence in the Berlin City Palace . In 1539 the first printing company went into operation in Berlin. In 1567, the three-day “ stick war ” between Berlin and Spandau developed from a planned drama , in which the Spandau residents refused to accept the defeat in the drama and ultimately beat up the Berliners. The watchmaker's guild was founded in 1552. Elector Johann Sigismund converted from the Lutheran to the Reformed creed in 1613 .

In the first half of the 17th century, the Thirty Years' War had dire consequences for Berlin: a third of the houses were damaged and the population halved. Friedrich Wilhelm , known as the Great Elector , took over government from his father in 1640. He started a policy of immigration and religious tolerance. The connection of the Oder and Spree by the Friedrich Wilhelm Canal from 1668 onwards brought economic advantages for Berlin due to lower freight costs. (See also: Economic history of Brandenburg-Prussia )

As a result of the Thirty Years' War, the construction of a fortress around the city began in 1658 under the direction of Johann Gregor Memhardt , which was completed around 1683. The city of Friedrichswerder, newly founded in 1662, and the suburb of Neu-Kölln were within this fortification. The old bridle path to the zoo was expanded into an avenue from 1647 and planted with linden trees. North of it, the second city expansion Dorotheenstadt was created from 1674 . The third Neustadt was Friedrichstadt , which was built from 1691. In front of the gates of the fortress was the Spandauer Vorstadt in the north, the Stralauer Vorstadt in the east and the Georgenvorstadt in between , the Köpenicker Vorstadt in the south and the Leipziger Vorstadt in the south- west.

In 1671, 50 Jewish families displaced from Austria were given a home. With the Edict of Potsdam in 1685, Friedrich Wilhelm invited the French Huguenots to Brandenburg. Over 15,000 French came, 6,000 of whom settled in Berlin. By 1700, 20 percent of Berlin's residents were French and their cultural influence was great. Many immigrants also came from Bohemia , Poland and Salzburg . Friedrich Wilhelm also built up a professional army .

To bring the two Protestant denominations in Brandenburg closer together, the Berlin Religious Discussion took place in 1662–1663 . The first church to be built for the supporters of the Reformed Church was the Parochial Church, built in 1695 . The Berlin Huguenot community had the French Friedrichstadtkirche built (consecrated in 1705).

Royal residence city (1701–1806)

Under King Friedrich I (1701–1713)

The desired increase in rank to the Prussian king was achieved by Elector Friedrich III. 1701, Berlin became the capital of the Prussian state . On January 17, 1709, the edict for the formation of the Royal Residence Berlin was issued by amalgamating the cities of Berlin, Kölln, Friedrichswerder, Dorotheenstadt and Friedrichstadt. After a few administrative changes that were necessary for this, the unification took place on January 1, 1710. The residents of the Berlin and Kölln suburbs received civil rights in 1701 and were thus treated as equal to the city dwellers.

Lützenburg Palace, built for Electress Sophie Charlotte west of Berlin from 1696 onwards, was renamed Charlottenburg Palace after her death in 1705 , the neighboring settlement was named Charlottenburg and received city rights.

With the start of construction of the armory in 1695, the representative expansion of the later street Unter den Linden began. Andreas Schlueter redesigned the Berlin Palace. Not the old Berlin main street, the Königsstraße , but Unter den Linden became the “via triumphalis” of Prussia. From now on the urban development shifted the focus to the new towns in the west.

In order to make the royal seat the center of the arts and sciences, Elector Friedrich III. In 1696 the Academy of Mahler, Sculpture and Architecture Art , and in 1700 the Electoral Brandenburg Society of Sciences , its first president was Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz . Both institutions moved into the upper floor of the royal stable ( Marstall between Unter den Linden and Dorotheenstraße , today the property of the State Library ). The Berlin observatory was inaugurated there in 1711 . The Collegium Medicum was established as the highest health authority in 1685 . Outside the city wall, a "Lazareth" for plague sufferers was built in 1710 , which was converted into a community hospital under the name Charité in 1727 . The electoral library was laid out as early as 1661 . The first newspaper in Berlin appeared in 1617 and had a monopoly under a different name until the middle of the 18th century, since 1751 this was unofficially called the Vossische Zeitung . The " Große Friedrichshospital " was founded in 1702 in the Stralau suburb.

Under Friedrich Wilhelm I (1713–1740)

Friedrich's son, Friedrich Wilhelm I , King of Prussia, in power from 1713, was a thrifty man who enlarged the standing army and built Prussia into an important military power. In 1709 Berlin had 55,000 inhabitants, of whom 5,000 served in the army, in 1755 there were already 100,000 inhabitants and 26,000 soldiers. In addition, Friedrich Wilhelm let the excise wall around the town build a wooden wall with 14 gates, where the excise duty levied on imported goods, as well as protective tariffs. The wall also had control functions and was intended to prevent soldiers from escaping. New parade grounds and military buildings were built in and around Berlin. In the Broad Street often punishments found by running the gauntlet instead.

To the northwest of Berlin, Friedrich Wilhelm I had the Royal Powder Factory built from 1717 to 1719 and settled French immigrants, Moabit arose. The entrepreneur and high official Johann Andreas Kraut participated in the founding of the Royal Warehouse , Berlin's largest manufactory. The banking and trading house Splitgerber & Daum was an important large company . The first trading session of the stock exchange , which was founded in 1685, took place in 1739 in the Neues Lusthaus in the Lustgarten. One of the first insurance companies in Germany was founded in 1718 with the fire society. The Chamber Court , which has existed since 1468, moved into the new building of the Kollegienhaus in Lindenstrasse in 1735 , the first large administrative building during the reign of Friedrich Wilhelm I.

The Quarree , Octogon and Rondell gate squares were laid out in the 1730s under the senior building director, Philipp Gerlach . The Gendarmenmarkt was built in 1688 according to plans by Johann Arnold Nering . The new towns were characterized by an orderly street grid with straight streets that offered wide perspectives. The citizens of the royal city extensions were obliged to billet soldiers with their families in their homes. French immigrants settled from around 1716 on the southern edge of the zoo, which later became the zoo district . In front of the previous building of today's Brandenburg Gate, there was a parade ground from 1730, from which the Königsplatz, today's Platz der Republik (Berlin) , later emerged.

Under Frederick the Great (1740–1786)

In 1740, Frederick II , known as Frederick the Great , came to power. Frederick II was also called the philosopher on the throne because he corresponded with Voltaire , among others . Under him, the city became the center of the Enlightenment . The most famous Berlin philosopher of the time was Moses Mendelssohn . The focal points of the Berlin Enlightenment were the literary circle of friends around the publisher and writer Friedrich Nicolai in his house on Brüderstraße and the Monday Club . The Berlin Wednesday Society published the Berlinische monthly magazine. Several associations of Freemasons emerged, and associations such as the Society of Friends and the Society of Friends of Naturalists were founded.

The construction of the Forum Fridericianum began in 1741 with the laying of the foundation stone for the opera house under Knobelsdorff . The Royal Library was built according to plans by Georg Christian Unger . The Royal Porcelain Manufactory was founded in 1763. Sugar boilers emerged. In 1723, Johann Georg Wegely founded a woolen manufacture on Speicherinsel, which is now part of Fischerinsel . The banker and trader Veitel Heine Ephraim had the house built, which has become known as the Ephraim Palais . (See also: Mercantilism ) The Invalidenhaus was opened in 1748 to take care of the war victims . During the reign of Frederick II, new barracks were built in which members of the military and their families were quartered.

Significant buildings for the trade in goods were built on the Spree, such as the old and new Packhof or the share store and the flour house . Goods and building materials were mainly transported with the coffee boats .

The fortress, which was now militarily obsolete, was demolished in 1734. In 1750, when the Spandau Gate was demolished , the city commander in charge, Graf von Hacke , had a square created that soon became Hackescher Markt . In 1712, the Spandauer Vorstadt received its own church in Sophienstrasse . During the Seven Years' War , the Prussian capital was briefly occupied by enemies of Prussia twice: in 1757 by the Austrians and in 1760 by the Russians .

Under Friedrich Wilhelm II. (1786–1797)

The accession to government of King Friedrich Wilhelm II in 1786 meant a phase of cultural upheaval for Berlin. After King Friedrich II had ruled and resided mainly from Potsdam, the court and government under Friedrich Wilhelm II have now been moved back to Berlin. The city became the undisputed capital of Prussia again, which attracted artists, tradespeople and entrepreneurs.

Modernization of the wall ring and the city gates

Despite the new cultural and economic impulses of the court, Berlin with its wall ring still differed significantly from a modern city in which the settlement core can no longer be separated from the surrounding area and the suburbs. In 1793, a 17-kilometer-long and four-meter-high excise wall surrounded Berlin, which was only 13 square kilometers in size. In four hours the entire city could be hiked along the wall. Only the Rosenthal suburb, inhabited by craftsmen, a few bourgeois summer houses and excursion restaurants were outside the city wall. Friedrich Wilhelm II had the wooden palisades of the wall ring replaced with fire-proof brickwork. Construction was completed by 1802, i.e. within 15 years.

The Berlin city gates, which had not been repaired since 1735, also had to be renewed. The first preparatory work had already started under Friedrich II in 1786, but most of the work could only be completed under Friedrich Wilhelm II. The city gates were still necessary, on the one hand, to control travel traffic and the customs duties to be paid on goods and, on the other hand, to make desertion and flight more difficult for soldiers. Berlin could be entered through a total of 14 city gates; the Brandenburg Gate in the west, the Hamburger Tor in the northwest, the Oranienburger Tor in the north, the Rosenthaler Tor in the north, the Schönhauser Tor in the northeast, the Frankfurter Tor in the east, the Schlesisches Tor in the east, the Königstor , the Hallesches Tor in the southeast , the Stralauer Tor in the south, the Kottbusser Tor in the southwest and the Potsdamer Tor in the southwest.

In April 1788, Frederick William II was. With the construction of the Brandenburg Gate today's landmark of the city in order. The previous building - a modest, single-lane baroque gate - no longer met the royal need for representation. This was also due to the significant location. The Brandenburg Gate was within sight of the Berlin City Palace and bordered the Tiergarten, an important excursion destination for the royal family. The Brandenburg Gate was built primarily as a memorial to the victorious Prussian invasion of Holland and the resulting alliance between Prussia, Great Britain and the Republic of the Seven United Provinces . The king demanded that the Brandenburg Gate should be based on the Propylaea of Pericles and the gateway to the Acropolis in Athens. With this he underscored his claim to be the leading power of the new alliance like Athens in the Attic League and to have established a “golden age” of peace on this basis.

Brandenburg Gate in the west

Hamburger Tor in the northwest

Oranienburger Tor in the north

Rosenthaler Tor in the north

Potsdamer Tor in the southwest

Culture and politics

At the end of the 18th century Berlin was one of the centers of the European Enlightenment . Professors, teachers, artists and civil servants developed a way of thinking that was increasingly independent of the court. As a result, salons, reading and theater societies became meeting places for cultural and political debates. The interest in literature that was read and discussed together made members of all classes come together in the Berlin salons. Women and Jews also gained “freedom” that they did not have outside of the salons. Above all, the salons of the writers Henriette Herz or Rahel Varnhagen stand out.

In the enlightened milieu of Berlin, the French Revolution , which broke out in 1789, attracted a great deal of attention. The major Berlin newspapers in particular - the Vossische Zeitung and the Spenersche Zeitung - provided detailed and reliable information about the events in Paris , even about the execution of Louis XVI. Despite the censorship dictation of 1788, the French Revolution was celebrated in the Berlin press as the “victory of reason over aristocratic presumption and royal mismanagement”. Nevertheless, Berlin was not in a preliminary revolutionary stage. The city's readership - mainly members of the educated middle class and the bureaucracy - were financially dependent on the state and the court. With the terror under the Jacobin regime, the positive response to the French Revolution in Berlin finally began to lose its influence. Friedrich Wilhelm II reacted to the publications with rejection. Even before the outbreak of the French Revolution, he wrote to a minister about the practice of "press righteousness" that existed in Berlin.

While Berlin had developed into the largest city in what is now Germany under Friedrich II., The city became one of the leading centers of the Classical era under Friedrich Wilhelm II. The Prussian capital vied for artists, architects and scholars on an equal footing with Vienna and Weimar. Frederick II had called French poets and Italian composers to Berlin, but ignored German cultural greats such as Herder, Goethe, Mozart and Beethoven. In the last years of Frederick II's reign, the theater and opera system had not been adapted to contemporary tastes either in terms of architecture or content. The auditorium of the Royal Opera House Unter den Linden therefore had to be rebuilt in 1787 by the chief building director Carl Gotthard Langhans , the architect of the Brandenburg Gate. The palace theater in Charlottenburg was also built under Friedrich Wilhelm II. The former French Comedy House on Gendarmenmarkt was renamed the German National Theater , where the plays were performed in German for the first time. Another cultural revolution consisted in the fact that, unlike under Friedrich II, modern plays such as Schiller's Don Karlos , Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice and Goethe's Iphigenie on Tauris were allowed to be played in the National Theater.

The professionalization of the Berlin arts and crafts at this time can be traced back to the reform of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts and Mechanical Sciences by Friedrich Anton von Heynitz . As a curator, he transformed the academy into an efficient training institute for painters, architects and artisans. Organized art exhibitions at the academy also created an artistically interested public in Berlin for the first time, to which the king also made some of his art collection accessible. With Friedrich Wilhelm II, the Rococo architectural style , to which Frederick the Great had clung to throughout his life, was replaced by classicism, which had long been established outside of Prussia . Important artists such as the graphic artist and illustrator Daniel Chodowiecki or the sculptors Johann Gottfried Schadow and Christian Daniel Rauch or the architects Carl Gotthard Langhans , Friedrich Wilhelm von Erdmannsdorf , Carl von Gontard and David Gilly worked in Berlin.

Numerous magnificent court palaces were built. The Bellevue Palace was completed 1786th

Infrastructure and social situation

The infrastructure of Berlin was still in its infancy under Friedrich Wilhelm II. It was not until 1789 that the paving of the Unter den Linden boulevard began . The main urban traffic was concentrated here, as the adjacent alleys and streets were hardly passable due to the heaps of dung, bulky waste and rubble. Private toilet pits and livestock farming within the wall contributed to the stink. Sandy street floors were often thrown up by the crowd, so that "clouds of dust" were mentioned again and again in contemporary reports. The writer Marie-Henri Beyle complained about how just someone "had the idea of founding a city in the middle of all that sand". Friedrich von Coelln even noted that Berlin could be “in the sandy deserts of Arabia ”. Because of the lack of a sewer system, the Berliners poured rubbish and faeces into the gutter and emptied their chamber pots into the gutters. The municipal cleaning service could hardly keep up with the quantities of faeces, waste and rubbish. Very few districts were lit by oil lanterns. For reasons of economy, the amount of oil was only enough to keep the lights on until midnight.

Notable progress has been made especially in the expansion and repair of the roads. These previously only consisted of a “pack of uncut stones” over which loose gravel was applied. On April 18, 1792, Friedrich Wilhelm II ordered a paved main traffic route to be laid between the royal cities of Berlin and Potsdam, which later became Berlin-Potsdamer Chaussee . The maintenance of the facility turned out to be difficult, however, as the user fees were far lower than expected by the government.

In the 1790s there was a crisis in the textile industry across Europe, from which Berlin was particularly hard hit, as the textile sector was the largest occupation in the city with 25,000 people. Cheaper production by children and women on the one hand and the relocation of weaving work to the countryside on the other hand depressed wages in the city. As a result, the weavers' guild and guild members organized a strike in 1793, which resulted in violent clashes with the military. Only a fraction of the approximately 13,000 unemployed found accommodation in orphanages and hospitals.

Reforms, restoration period, founding of an empire (1806–1871)

French period (1806-1808)

French capture of Berlin

In 1806 Berlin felt the consequences of the Prussian policy of neutrality that had been pursued since 1795. The royal government entered the Fourth Coalition War almost unprepared militarily and politically . After the devastating defeat against the French Emperor Napoleon I in the double battle near Jena and Auerstedt on October 14, 1806, a successful defense of Berlin was impossible. The unpaved tariff wall was unsuitable for repelling an attack. There were also not enough troops stationed in Berlin. After rumors of a Prussian victory had briefly reached Berlin and were celebrated, the full extent of the Prussian defeat became known on the night of October 16-17, 1806. The deputy governor of Berlin, Count Friedrich Wilhelm von der Schulenburg-Kehnert , was aware that the French capture was only a matter of time. For this reason he tried to maintain the social order by counteracting the patriotism of the Berliners. So he turned down the request to set up a voluntary Berlin citizen militia that wanted to fight the French army in the Brandenburg area. In a famous appeal on October 17, 1806, he announced on walls:

“The king lost a bataille. Now rest is the first civic duty. I urge the residents of Berlin to do so. The king and his brothers live. "

Despite the prescribed calm, there was a confusing hustle and bustle in Berlin. To get news, many Berliners gathered on the streets. The mood was mixed. Some residents expressed their loyalty to the royal family, others scoffed at the escape of the princes, government and officials, while others openly expressed their anger at the politicians. Even expressions of sympathy for Napoleon are said to have been heard. The confusion in the city led to the armory overlapping ammunition and weapons were not taken away. With a time lag, wealthy middle-class families followed the example of the authorities and left for East Prussia. They hoped that their abandoned Berlin apartments would be less attractive for billeting French soldiers.

Between October 18, 1806 and December 23, 1809, Berlin had de facto lost its function as the seat of the Prussian crown, state authorities and the court. During this time Memel and Konigsberg replaced Berlin, which was within reach of the French armies. Balls, exhibitions, festivals, theater and opera performances declined in Berlin without government funding. After the first two French divisions penetrated through the Kottbusser and Hallesche Tor on October 23, 1806 , Napoleon presented himself as the victorious general on October 27, 1806 during his entry through the Brandenburg Gate: the one between the Great Star and the Brandenburg Gate on both French cuirassiers standing on the side of a trellis received Napoleon with “vive l'empereur” calls ( German : “Long live the emperor”), which at least some Berliners joined. The French military commander ordered that all of Berlin's bells should be rung in honor of Napoleon and that women should waving white towels on the windows. In front of the Brandenburg Gate, the Berlin magistrate handed Napoleon the keys to the city.

There are only contradicting witness reports about the mood of the Berlin residents at the beginning of the French occupation. Memoirs in this regard, which took an attitude hostile to France , as a rule did not emerge until more than 40 years after the entry of the French troops, i. H. at a time when a positive assessment of the Napoleonic era was associated with the risk of being accused of collaboration . Especially advocates of reform from the aristocracy and bourgeoisie welcomed French rule at first. The nationally minded Berlin writer Adolf Streckfuß complained about this attitude:

"Was it surprising (...) if a people, to whom no rights had been granted until now, which had only been regarded as a tax-paying mass, had always been treated with impudent arrogance, had no patriotism?"

The economic pressures of the occupation caused a gradual change of mood in the city to the disadvantage of the French. Nationalist ideas of revanchism, however, were still mainly limited to parts of Berlin's educated bourgeoisie.

French occupation

In Berlin, Napoleon pursued two goals: First, he had to secure the financing of his expansion policy through contributions , billeting, army deliveries and art theft. In order to stimulate French industry and trade, too, he was dependent on economically squeezing out defeated Prussia. Second, a possible uprising by the Berliners had to be prevented, which otherwise would have tied up too many French troops, especially since the war in East Prussia was still going on. However, since state authorities that could have collected taxes and payments had mostly fled Berlin, Napoleon had to ensure the establishment of a new administration loyal to him. For this purpose, on October 27, 1806, Napoleon had the Berlin city magistrate and the civil governor summoned to his quarters, the Berlin City Palace. The magistrate was supposed to name 2,000 wealthy citizens, who then elected 60 people from among their number to head the provisional general administration. The general administration in turn had to appoint a seven-person "administrative committee". It was supposed to replace the city magistrate. In addition, on November 3, 1806, Napoleon ordered the formation of a 1200-man civil guard under French command to maintain public order.

Between 1806 and December 1808 there were never fewer than 12,000 soldiers stationed in Berlin, including troops from the Confederation of the Rhine, allied with Napoleon . The barracks in Berlin from the time of Frederick the Great were insufficient to accommodate the 30,000 men at times, which is why most of them had to be quartered in private apartments. In order to secure their supplies for as long as possible, the French military leadership tried to prevent excesses by imposing severe penalties. Nevertheless, there were isolated cases of looting, extortion and violent escalations between residents and soldiers. In dealing with the apartment owners, the French general Pierre Augustin Hullin admonished his soldiers "to share the usual meal (...) and not to ask for it under any pretext". Meat, wine and bread were to be obtained from military supply stores in order to relieve the civilians. Citizens who could not give the soldiers quarters had to pay lodging fees. In the two years, the soldiers' two-year catering devoured 8.6 million thalers. As a result, trade and production fell significantly. Napoleon's trade war against Great Britain hit the “luxury and textile industry” so important for Berlin hard. The poor harvest of 1807 did not improve the economic situation either.

Art theft

As with his previous campaigns, Napoleon did not arbitrarily plunder castles and collections. He systematically transported works of art from occupied countries to Paris. The general director of the Musee Napoleon , Dominique-Vivant Denon , gave him a hand. Denon selected the most important works of art by visiting all of the royal collections in Potsdam, Charlottenburg and Berlin and examining their inventory lists. The meticulous recording made it possible for Napoleon to be returned to Berlin after the defeat. Denon selected 116 paintings, 204 statues, busts and reliefs, thousands of coins, 25 items made of ivory and 23 made of amber. Two ships were needed to get the boxed cargo to the French capital. As early as November 11, 1806, Denon informed the artist Johann Gottfried Schadow in his studio that Napoleon had personally ordered his work, the Quadriga of the Brandenburg Gate , to be dismantled. It was to be set up again on a Paris triumphal arch that had not yet been specified. The complaint by Schadow and other artists, who expressed them in a letter to Napoleon, that the copper work could be damaged during transport, was never to reach the emperor. From December 2 to 8, 1806, the Quadriga was finally dismantled by the Potsdam coppersmith Emmanuel Ernst Jury and loaded onto a ship on December 21, 1806. Until 1814, the only reminder of the Quadriga was an iron fastening rod, which became a visible symbol of the Prussian defeat of 1806 in urban planning terms. From then on, Napoleon was mocked by the Berliners as a “horse thief”.

Only after the ratification of an agreement with France to implement the Tilsit Peace did the French withdraw from Berlin in December 1808.

Reform period (1807-1815)

Formation of an urban self-government (1807-1809)

The reaction to the obvious collapse of the old Prussian state was the Prussian reforms , which, beginning with the October Edict of 1807, initiated a process of transformation from feudal to civil society. Reformers such as Freiherr vom und zum Stein , the philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte or the theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher now campaigned for Berlin issues. One of their concerns was the creation of an urban self-government. State and city administration should be separated from each other. For this, as already indicated in the French period, important prerequisites had been created: The formation of the “Comité administratif”, a municipal administrative committee, forced by Napoleon in 1806, was the result of an election in the Petrikirche . With this, the citizens of Berlin gained legal participation in urban affairs for the first time during the time of the Prussian monarchy. Of course, only the wealthiest citizens of Berlin took part in the election. Probably the act was an acclamation ; H. a vote by shouting. On November 19, 1808, the new town ordinance was adopted under Stein and introduced in Berlin on January 26, 1809. In the future, the city's area of responsibility should include matters relating to schools, churches, poor relief, fire protection, prisons and lighting. Control of the courts and the police remained with the state.

First, the Berlin magistrate was commissioned to prepare the election of a city council . Only homeowners and earners with an annual income of at least 200 thalers had the active right to vote, only about seven percent of the population. According to the 102 city councilors to be elected, Berlin was divided into 102 electoral districts by the magistrate. Each 34 districts should also elect a deputy. The elections took place from April 18-22, 1809 in 22 churches. The magistrate used the street names to inform voters in the newspapers to which constituency and which “electoral church” they were assigned.

The Berlin city councilors were determined by the so-called ballotage procedure . Citizens entitled to vote received a white and a black ball. While the white ball thrown in a ballot box counted as a yes vote, a black ball thrown in was counted as a no vote. With another ballot box, the voters got their inserted ball back so that the next candidate could be voted on. In each constituency, only the candidate with the most yes votes could be elected to a city councilor of Berlin. The magistrate published the names of the elected in the newspapers. Most of the city councilors were self-employed and landowners. Only six agents paid rent. In the session of May 1, 1809, the city council elected the noble Carl Friedrich Leopold von Gerlach , who came from the higher civil service, as the first mayor of Berlin. Gerlach received 98 of 99 valid votes and was on May 8th by King Friedrich Wilhelm III. confirmed in office. On May 16 and 17, a new magistrate was elected , which dissolved the old one from 1806. Of course, most of the members of the new magistrate already belonged to the previous one. On July 6, 1809, the replacement of the old city authorities (magistrate and the Napoleonic “Comite administrativ”) was symbolically celebrated: they were “released” from their offices in the Berlin town hall in the presence of the new magistrate and city councilors. Then the assembly went to the Nikolaikirche , where the new magistrate was solemnly sworn in. The formal appointment of the magistrate was then carried out again in the Berlin City Hall.

Foundation of the reform university and spiritual renewal

The founding of the Berlin University was an indirect consequence of the Tilsit Peace of 1807 dictated by Napoleon. Since Prussia had to cede its territories west of the Elbe, Halle an der Saale, its most important university, fell to the newly created Kingdom of Westphalia . To compensate for this loss, a university was opened in Berlin in October 1810. The facility moved into the former palace of Prince Heinrich . The building had lost its previous function since 1802 or the death of Prince Heinrich , a younger brother of Frederick the Great. The later success of the Berlin University was mainly due to Wilhelm von Humboldt's new “university concept” . As head of the department for culture and public education , Humboldt envisaged a unity of research and teaching. In addition, there was a relatively large freedom of learning and teaching until the Karlsbad resolutions of 1819. This attracted important scientists in the first third of the 19th century. They included the philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte , the theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher , Friedrich Carl von Savigny and, a little later, Georg Friedrich Hegel . Fichte became the first rector. Due to the lack of space, in the first few years the meetings often had to take place in the apartments of the scholars.

The existing numerous schools and small scientific institutions (such as the Academy of Arts, Building Academy, Training Institute for Mining and Metallurgy, schools for training the military or doctors) had to be reformed in order to be more effective. The educational system was reorganized under the direction of Wilhelm von Humboldt.

Berlin's first daily newspaper appeared between 1810 and 1811, the Berliner Abendblätter published by Heinrich von Kleist . Located in the street at the Stechbahn located Volpische cafe (coffee houses were built in Berlin from 1721), later café josty , became a popular public meeting place for the middle class just as well as the wine bar Lutter & Wegner am Gendarmenmarkt .

Further reforms and the time of the "Wars of Liberation"

The Prussian State Chancellor Karl August von Hardenberg continued the reform policy of the Baron vom Stein. In economic terms, at least de jure, the change from state-controlled mercantilism to a free-trade market system took place under him . Together with an edict to introduce trade tax , Hardenberg introduced freedom of trade in Prussia in 1810 . From then on there was no longer any compulsory guild, i. H. the city guilds no longer controlled the training and production conditions in the respective craft branches. From then on, Berlin craftsmen could choose their trade themselves and train apprentices. This was an important prerequisite for the later industrialization of Berlin. For safety reasons, qualifications were only required for 34 occupational groups, for example for chimney sweeps and surgeons. In practice, however , the guilds often maintained an important position in the city's economic life for decades. Above all, the magistrate and the city council were hostile to the freedom of trade. In 1826, all the master craftsmen of the brush binders and tanners belonged to a guild. After all, the guilds offered “social security mechanisms that were no longer applicable ” ( Armin Owzar ). Many skilled trades became impoverished as a result of the ever increasing competition from immigration from the countryside and superior industrial mass production.

In 1812 an edict declared equality for Jews . As full citizens, they were no longer obliged to pay special taxes for their “protection”. Jews should also no longer be excluded from commercial activities. They were given the right to hold municipal and academic offices. However , this did little to change the widespread anti-Semitism . As recently as 1810, the nationalist writer Ernst Moritz Arndt had called in Berlin to allow Jews to enter the country “under no pretext and with no exception”. Between 1815 and 1848, the edict of 1812 was even restricted again. In the pre-March period , access to civil service was closed to Jewish citizens.

Further reforms included the renewal of the army. The king returned to Berlin with his entire court at the end of 1809. When the Napoleonic troops returned to Berlin in the course of their Russian campaign in 1812, there was a temporary standstill. This renewed occupation ended after Napoleon's devastating defeat in 1813, by then even many Berliners had volunteered for the Russian army. When Napoleon was defeated, General Blücher arranged for the immediate return of the Quadriga to Berlin (see also → here ). It was again placed on the Brandenburg Gate, and an iron cross and a Prussian eagle were added to the staff of the goddess of victory based on a design by Karl Friedrich Schinkel . Many Berliners linked the victory over France with the hope that a new path to a democratic future could be taken. Friedrich Ludwig Jahn started the gymnastics events in the Hasenheide in 1811 . The defeat of the French in 1814 also marked the end of further reforms.

The Botanical Garden was built on Potsdamer Strasse in 1809 and was relocated to Dahlem at the end of the 19th century .

Vormärz (1815–1848)

Population growth and the beginning of the industrial revolution

With the end of the Napoleonic Wars , Prussia and its capital began a decade-long period of peace. Social and political development within Berlin was accelerated without any military interference from outside. A major factor in this was the rapid growth of the population. While only about 200,000 people lived in the city in 1816, in 1840 there were already 330,000 and in 1846 even 408,000 inhabitants. Around 1850 Berlin had grown to become the fourth largest city in Europe after London , Paris and Vienna. The doubling of Berlin's population in Vormärz can be explained on the one hand by an annual birth rate of 30 percent (i.e. 300 live births per 1000 inhabitants) and on the other hand by high immigration. With the peasant liberation of 1807 (see the October edict ), the rural population was able to immigrate to Berlin for the first time. As a large city with charitable organizations, diverse work opportunities and leisure activities, Berlin exerted a great attraction on its surroundings. Only every second inhabitant of the city was born in Berlin. The increase in population was only comparable to that of the major English industrial cities and was even higher than in Vienna or Paris. Most of the new Berliners came from the agrarian Prussian provinces of Brandenburg and Silesia . Unused to the city's economic competition, most of the immigrants slipped into poverty. They worked as day laborers, coachmen or house servants.

The Prussian railway network, which has been growing since the late 1830s, laid the foundations for the beginning of the industrial revolution , the second important development in Vormärz-Berlin alongside population growth. In 1840 there were only 185 kilometers of railway line in Prussia, in 1843 it was already 815 kilometers and in 1847 1424 kilometers. Thanks to this emerging transport network, the north of Berlin developed into an important mechanical engineering location. The industrial city of Berlin was the first that a traveler saw when approaching the city. A report in the Spenersche Zeitung from 1840 gives a good impression of the situation :

“When we enter a high point near Berlin, the sight of the obelisk-like chimneys with their towering columns of smoke is a strange sight. These strange colossi are a product of the most recent times and, as they now surround the residence in the north, south, east, west, they appear, as it were, to be the seat of the Cyclops who want to defend the entrance to the city. "

Nevertheless, at that time one cannot speak of a real industrial workforce in Berlin. According to information calculated from contemporary employment statistics, the number of journeyman craftsmen in Berlin was twice as high as that of industrial workers in 1848. As the historian Rüdiger Hachtmann emphasizes, it must be taken into account that the people included in the documents under the term industrial workers were often actually worse-off master craftsmen. Berlin society consisted of three large social groups: the bourgeoisie (including factory owners, large merchants, high officials, teachers, journalists, etc.) made up almost 5%, the middle class (including large craftsmen, private officials, carters, etc.) made up almost 11% and the Lower class (including small craftsmen, journeymen, factory workers and service personnel) almost 85% of the working population of Berlin.

Development of the Berlin railway system

At the beginning of the 1830s there was still resistance to the construction of a Berlin railway network, particularly in the Prussian government and bureaucracy. This was due to the fact that the Prussian government's focus was still primarily on the expansion of highways. The new technology, on the other hand, was distrusted, especially since state lands were affected when the tracks were laid. In 1834, the Prussian Ministry of the Interior refused to build a railway line between Berlin and Leipzig. A turning point only occurred through the efforts of the Berlin lawyer J. C. Robert, who was King Friedrich Wilhelm III. presented a plan that reduced the railway line from Berlin to Potsdam. The king then led an investigation of the plan by the State Ministry, which certified the enterprise an economic benefit. In a cabinet order dated January 16, 1836, the Prussian king confirmed the approval for the construction of the rails. Finally, a number of private shareholders succeeded in founding the Berlin-Potsdam railway company in 1837 , which was supposed to raise the financing with start-up capital of 700,000 thalers. Within 14 months, a single-track line was built from the square in front of the Potsdamer Tor via Zehlendorf to Potsdam . With the exception of rail bolts and car bodies, which were manufactured in Berlin, all technical products such as locomotives and tracks came from England . On September 22nd, 1838, the line was put into operation as the first Prussian railway line.

In the 1840s, the railroad had become an important means of transport in Berlin: in 1847 and 1848, 1.5 million travelers reached or left the city via the rail network. The line to Anhalt, completed in 1841, connected Berlin with the Kingdom of Saxony from then on. The line to Potsdam was extended to Magdeburg by 1844 . Until 1846, Berlin received a connection to Breslau via Frankfurt an der Oder . In the same year the connection to Hamburg followed . As early as 1844, the railway lines connected Berlin with all four cardinal points. This led to an acceleration in communications, commerce, industry and personal mobility. The train stations on the outskirts were connected to each other and to the city by horse-drawn buses . Around 1840 around 1000 cabs and other wagons were in use. As a rule, they were still run by private companies, which, however, could not raise enough capital in the long term and would disappear in the next few decades.

The first locomotive built by Borsig drove from the new Anhalter Bahnhof in 1841 . The Szczecin train station started operating in 1842. In the same year, the Frankfurt train station was opened, which was the only one inside the customs wall . The fifth terminus station was inaugurated as the Hamburger Bahnhof in 1846 . The streets that ran from the city center to the train stations became major arteries. In the decades that followed, Leipziger Strasse changed from a residential street to a commercial street where the large department stores were located.

Side effects of the industrial revolution

The social problems and the housing shortage associated with population growth and the industrial revolution led to a huge building boom. First of all, the open spaces within the wall ring were built on. However, for reasons of space, most industrial companies settled on the city periphery, where they were followed by the workers' settlements. Especially in the area of the Oranienburger and Rosenthaler Vorstadt , Berlin grew well beyond its walls. The first so-called ' tenement barracks ' developed in the Berlin suburbs . In these apartments it happened that several families had to share a room that was only symbolically separated by chalk lines or a string. A contemporary police report shows that 2500 people were accommodated in only 400 rooms in front of the Hamburger Tor alone. Common practice also included the admission of so-called “ sleeper boys ” who were admitted to the apartment for a few hours for a fee. This type of subletting could reduce your own rental costs.

A comprehensive program of business promotion was carried out under the direction of Peter Beuth and the business institute was set up in 1821 to improve business training . The Royal Prussian Iron Foundry began its work in front of the Oranienburger Tor in 1804 . Other companies followed, such as August Borsig's mechanical engineering institute in 1837 . The industrial area in the Oranienburger Vorstadt was soon named Tierra del Fuego . New mechanical engineering factories emerged, such as the works of Louis Schwartzkopff , Julius Pintsch or Heinrich Ferdinand Eckert , and Carl Justus Heckmann's company became the leader in apparatus engineering .

The Prussian state needed faster means of communication for the administration and control of the Rhine provinces far away from the capital. Starting from the Berlin observatory on Dorotheenstrasse, an optical telegraph line via Potsdam to Magdeburg was completed by the end of 1832 , and it was later extended to Koblenz .

From 1825, the central gas supply was set up, especially for street lighting . The English Imperial Continental Gas Association's first private gas works in front of Hallesches Tor went into operation in 1826. Two municipal gas works, which later became GASAG , were built in the mid-1840s on Stralauer Platz and on Gitschiner Straße ( Böcklerpark ).

In 1800 the Berlin Mint moved into its new building on Werderscher Markt. Not far away on Jägerstrasse was the Königliche Hauptbank, founded in 1765 (from 1847 Prussian Bank , from which the Reichsbank emerged in 1876 ). Since 1815, the Mendelssohn banking house has had its headquarters on Jägerstrasse. In the neighborhood was the building of the state sea trading company , which was active in the financing of the railway construction.

The cholera epidemic reached Berlin in 1831, during which around 2000 residents fell ill. Child labor in the industry with high daily working hours was common. Average life expectancy in mid-century Berlin was 54 years for higher occupations and 42 years for industrial workers.

As early as the 1820s, Friedrich-Wilhelm-Stadt was formed as a separate district. By 1841, the city limits were extended beyond the customs wall, the Oranienburger and Rosenthaler Vorstadt were added, as well as the outer Luisenstadt, the outer Stralau district and the outer Königsviertel as well as the Friedrichsvorstadt . Peter Joseph Lenné took over the urban planning from 1840. Building inter alia Based on ideas from Schinkel, in 1840 he presented the "Projected jewelry and border trains from Berlin with the immediate vicinity", in which the expansion of the Landwehr Canal (inaugurated in 1850) was proposed.

Culture and science

As head of the Oberbaudeputation , Karl Friedrich Schinkel redesigned the architectural center of Berlin. In chronological order he had the Neue Wache , the theater , the old museum , the Friedrichswerder Church and the building academy built. The architectural focus on Greek antiquity gave Berlin the nickname Spree-Athens , but the term was coined for Berlin long before Schinkel. The poet Erdmann Wircker used the term 1706 to express praise to King Friedrich I of Prussia. The Berlin cityscape aroused criticism from contemporaries in the 19th century. A largely missing medieval building fabric was criticized. Berlin seems too “sober and without history”. The first public building in Berlin, which emerged after the Napoleonic Wars, was built by Schinkel 1816-1818 New guard at the Boulevard Unter den Linden . Located near the city palace, it served as the headquarters of the royal guards. On July 29, 1817, while the Neue Wache was being built, the theater on Gendarmenmarkt burned down . King Friedrich Wilhelm III. commissioned Schinkel to rebuild the facility in 1818. Three years later the theater could be reopened with the performance of Goethe's Iphigenie auf Tauris . Although there were plans for a museum building in Berlin as early as the 18th century, this ambition could only be realized in 1830 and under Schinkel's supervision: The Old Museum on the edge of the Lustgarten was part of a building ensemble that, according to the understanding of time, was a unity of art (Alte Museum), religion (Berlin Cathedral), military (armory) and state (city palace). At Werderscher Markt, a former riding house that had been converted into a church gave way to Friedrichswerder's church, which was built between 1824 and 1830. The neo-Gothic sacred complex was the first brick building in the center of Berlin since the Middle Ages.

King Friedrich Wilhelm IV relocated the Hohenzollern hunting grounds, which had been in the Great Zoo since the 16th century , to the wildlife park near Potsdam . He donated the vacated area with the local pheasantry and the 850 animals of the royal menagerie , which was located on the Pfaueninsel , to the people of Berlin. On this basis, the zoological garden, the oldest animal park in Germany , was created in 1844 .

In the pre-March period, many important scientists also worked in the city, such as the natural scientist Alexander von Humboldt , the historian Leopold von Ranke of the geodesist Johann Jacob Baeyer , the biologist Johannes Peter Müller , the geographer Carl Ritter , the mathematician Karl Weierstrass , the astronomer Wilhelm Foerster or the Doctor Albrecht von Graefe . From 1840 Heinrich Gustav Magnus set up one of the first physics institutes in Germany in Berlin. The composer Carl Friedrich Zelter , a resident of Berlin, wrote to his friend Wolfgang Maximilian von Goethe in 1817 : “The whole world in honor! But Berlin is a cheerful, free, easy and sociable place where you can live as you want. " Heinrich Heine said in his travel pictures in 1826:" Berlin is not a city at all, but Berlin just provides the place where there is a lot Gather people, including many people of spirit, to whom the place is completely indifferent. "

Relationship between court society and city

In the pre-March period , the royal court was still clearly separated from the industrial and civil city of Berlin. On the one hand, this was due to the lack of social permeability between the stands. The Berlin Palace was still the center of a “military-aristocratic exclusivity”. Access to court life was only granted to the highest levels of the Berlin business and educated bourgeoisie. The majority of academics, artists and writers, however, were completely excluded from it. Since there was still no fully developed communication and transport network and no parliamentary say, the court exerted little influence on public opinion until 1848. In addition, King Friedrich Wilhelm IV. And his court in Berlin in particular did not show any permanent presence. In spring the court loved to stay in the Potsdam City Palace, the early summer was often spent in Sanssouci, in August and September the king retired to Rügen and the Silesian Erdmannsdorf, in autumn he traveled to Potsdam for troop maneuvers and spent the Christmas season in the palace Charlottenburg. The appearance of Berlin as a residential city increasingly faded into the background due to the enormous growth of the urban area. The contemporary Friedrich Saß commented on this in 1846 with the following lines:

"Berlin has become too big for the court and the bureaucracy to control it completely."

Tensions between the government and the capital also intensified politically after 1815: the Prussian reformers were now replaced by conservative advisers to the king who worked towards a pre-revolutionary state and social order. Although the protest in Berlin against the restoration policy was rather small, the government sanctioned the national and liberal-minded gymnastics and student movement. In 1819 the closure of the gymnasium on the Hasenheide and a general ban on gymnastics was initiated. Berlin students and professors in particular were affected by arbitrary arrests, house searches, espionage and public denunciation in the course of the so-called “ demagogue persecution ”. Numerous plays and publications were censored or banned altogether, professors like Wilhelm Martin Leberecht de Wette lost their chair and theologians like Friedrich Schleiermacher were transferred to punishments. The hysteria of persecution ultimately resulted in a creeping alienation between the dynasty and the capital.

An expression of the political and social dissatisfaction in the Vormärz were unrest such as the tailoring revolution in 1830, the fireworks revolution in 1835 and the potato revolution in 1847. As a result of the poor harvest of 1846 and so-called potato rot , there was a critical shortage of food in Berlin. In January 1847, potato prices rose three to four times. Even the abolition of all import duties on flour and grain could no longer stop the price explosions. On April 21, 1847, riots broke out on the Gendarmenmarkt , which began with the looting of potato stalls. The unrest quickly spread to large parts of the city. Bakery and butcher shops were attacked. The fact that not only food was stolen, but windows and doors were smashed, appliances and furniture were damaged or taken away and shop signs were used as firewood shows that the protest was both a "punitive" action and a hunger revolt. Only with the help of military forces was it possible to bring the situation back under control on April 23, 1847.

Possible developments were only dealt with in the smallest of circles, and numerous “debating clubs” emerged.

Revolution of 1848/1849

→ see main article on the March Revolution of 1848 in Berlin

With all the progress, the political tensions were not allayed. The death of King Friedrich Wilhelm III. and the assumption of government by Friedrich Wilhelm IV. hardly changed the existing situation. The growing craftsmen merged in 1844 to form the Berlin Craftsmen's Association and thus also influenced the political education of the middle class. The Covenant of the Righteous was also established. The social problems in Berlin were highlighted particularly clearly by the news about the Silesian Weavers' Uprising. A bad harvest and the increasing persecution of dissidents led to the first unrest in the city.

On March 18, 1848, there was a large rally in which around 10,000 Berliners took part. The troops loyal to the king, however, were deployed and night barricade fighting began. By the end of this March Revolution on March 21, 192 people had died. However, unrest continued after that. On June 14, 1848, the armory was stormed and looted.

As a result of the uprising, however, the king made numerous concessions with his proclamation “To my dear Berliners”; Above all, freedom of the press and freedom of assembly were introduced, and the first political associations emerged from their entourage as forerunners of later parties. At the end of 1848 a new magistrate was elected. The economy had been declining in the previous decades, so that there were now a large number of unemployed. Emergency work was introduced, which led to the rapid expansion of Berlin's waterway system. These small improvements did not last long, however, in the late autumn of 1848 the king installed a new cabinet, on November 10th Prussian troops moved into Berlin again, and on November 12th the state of siege was declared . Many of the achievements of the revolution were thus ruined.

The introduction of electrical telegraphy enabled the Wolff Telegraphic Bureau to be founded in 1849 . The Gerson department store opened in 1849 as the first department store in Berlin on Werderscher Markt .

Reaction Era, New Era and Period of the Wars of Unification (1850–1871)

After a short break, in March 1850 a new city constitution and municipal code were adopted , according to which the freedom of the press and freedom of assembly were repealed, a new three-class suffrage was introduced and the powers of city councilors were severely restricted. The rights of Police President Carl Ludwig Friedrich von Hinckeldey , on the other hand, were strengthened. During his term of office until 1856, however, he also took care of the construction of the city's infrastructure (especially city cleaning , waterworks, water pipes, and the construction of bathing and washing facilities).

Prussia became a constitutional monarchy in 1850 . The two chambers of the Prussian Landtag , the mansion and the House of Representatives , had their seat in Berlin.

The building regulations of 1853 favored the development of the tenements in the following decades . A significant expansion of the city took place in 1861. Wedding with Gesundbrunnen , Moabit , the Tempelhofer and Schöneberg suburbs as well as the outer Dorotheenstadt were added. With the Luisenstadt Canal , completed in 1852 , the new Friedrich-Wilhelm-Stadt district was to receive an attractive open space. Further plans by Lenné for the north of Berlin followed in 1853.

The Berliner Handels-Gesellschaft , founded in 1856 and located between Französischer Strasse and Behrenstrasse, became important in the financing of industry . Disconto-Gesellschaft , founded in 1851 and for a long time one of the largest German banking companies, moved into a building on Unter den Linden. In the following decades the area developed into the leading center of finance in Germany.

In 1861 Wilhelm I became the new king. At the beginning of his reign there was hope of liberalization . In 1861 the urban area was expanded by the incorporation of Wedding and Moabit as well as Tempelhofer and Schöneberger Vorstadt .