Charles Abresch Company

| Charles Abresch Company | |

|---|---|

| legal form | Corporation |

| founding | 1871 |

| resolution | 1966 |

| Seat | Milwaukee , Wisconsin , USA |

| management | Charles Abresch, Louis Schneller |

| Branch | Carriages , automobiles , commercial vehicles , bodies , motorcycle sidecars |

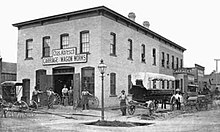

The Charles Abresch Company was a carriage and wagon manufacturer as well as an automobile, commercial vehicle and body manufacturer in Milwaukee ( Wisconsin , USA ). Brand names were Abresch and, for trucks, Abresch-Cramer ; there is also evidence of Abresch-Kremer's spelling .

Charles Abresch (1850-1912)

Charles Abresch was born on May 12, 1850 in Dierdorf (today the district of Neuwied , Rhineland-Palatinate ). His parents were the trained carpenter and cabinet maker Louis and Elisabeth Abresch born. Cutter. The mother died a few months after he was born. Louis Abresch emigrated to the United States in 1854 and settled in Milwaukee . Charles and his older brother Wilhelm (1844–1879) remained in the care of aunt Christine Schneller . Wilhelm completed an apprenticeship as a carpenter, Charles one as a blacksmith . The two brothers also emigrated to the USA , probably together and possibly with their cousins Louis and Wilhelm Schneller . Charles is known to set out on the journey in 1868. Her father had now remarried. His association with Elizabeth Leibrecht (born in Bavaria in 1833) produced five children.

Charles took a job at John Meinecke's Wagon and Carriage Works in Milwaukee, William - now William - worked as a carpenter in Kenosha ( Wisconsin ).

As early as 1871 Charles Abresch went into business for himself and founded the Second Ward Carriage & Wagons Works, C. Abresh, proprietor . In 1873 he married Katherine Gerard (1847–1926). In 1876 their only child, Amanda, was born. In 1884 the company was converted into a corporation. In the following years it grew into a market leader for brewery vehicles, was active nationally and exported to Mexico , the Philippines and Australia . Charles's father Louis Abresch died in 1887. In 1889 Charles tried to organize a company that would control the US motor vehicle market. This failed, and ten years later the Electric Vehicle Company in Hartford, Connecticut , equipped with the Selden patent , was in that position. In 1894 the Charles Abresch Company was capitalized at US $ 220,000 and employed over 800 people.

In 1899 Abresch experimented with a drive set invented by WF Davis , which could be retrofitted to any horse-drawn vehicle and turned it into an "automobile". Such avant-Trains found a limited distribution in the early days of motorization. Twice, in 1898 and 1902, the plant burned down completely and was rebuilt by Charles Abresch. Industrial disputes with strikes or lockouts are documented for 1900, 1910, 1911 and 1916. Abresch visited his relatives in their old homeland twice, in 1897 and 1906. In 1910 he organized his own truck production, which was given up shortly after his death.

Most recently Charles Abresch held the position of company president and chief financial officer in his company. He fell ill in early 1912. His condition worsened and he was treated at the Battle Creek Sanitarium in Battle Creek, Michigan, and then at the Sacred Heart sanitarium in Milwaukee. Two weeks before his death on April 27, 1912, he was released home. Obituaries appeared in the Milwaukee Journal on April 28, 1912, and in the May issue of Carriage Monthly , which emphasized that employees who had worked at Abresch's company for over 20 years carried the coffin. Accordingly, the burial took place on May 1, 1912 in the Forest Home Cemetery in Milwaukee.

In his obituary, Commercial Vehicle called him one of the “most progressive and successful vehicle manufacturers in the Midwest ”, and the Milwaukee Journal called his company “one of the largest plants of its kind in the country”, which he had built up through “constant and persistent work”.

Louis Schneller Jr. (1874–1939)

Louis Schneller Jr. was Charles Abresch's 2nd cousin ; the Abresch sons grew up in his grandmother's household in Essen . In an obituary on September 9, 1939 , the Milwaukee Sentinel stated that Louis had emigrated to the United States at the age of seven and had been associated with the Charles Abresch Company for almost 50 years. It is mentioned that he emigrated with his brother Wilhelm, so it is obvious that the entire family emigrated around 1881. A sister is also known, Paula, married. Paul , who is mentioned in the above obituary as a bereaved.

Accordingly, Louis Schneller jr. about 15 years old when he joined Charles Abresch's company. A Louis Schneller was already employed as plant manager in 1884. Louis Schneller jr. have acted; Obvious is his father of the same name. In Milwaukee: A Half Century's Progress, 1846–1896 , Louis Schneller, Jr. listed as plant manager.

After Charles Abresch's death, Louis Schneller led the company as President and Chief Financial Officer. He managed to lead the company through the difficult years of prohibition. He was a Freemason and a good friend of Republican Julius P. Heil , whose first campaign for election as governor of Wisconsin he supported. After Heil's successful candidacy, Schneller worked for him as a consultant. Heil, like Abresch and Schneller, was of German descent and an entrepreneur before he went into politics. The Wisconsin State Journal noted in another obituary that Schneller was president of the Washington Park Zoological Society . Louis Schneller was married to Wilhelmine "Minnie" Eissfeldt Schneller (1872–1959). He suffered a stroke at the end of August 1939 , which he died on September 7th.

Company history

Charles Abresch Company (1884-1893)

The company was founded in 1871 by Charles Abresch as the Second Ward Company and was run as a craft business (car manufacturing) for the next few years. In 1884 it was reorganized as the Charles Abresch Company as a public company. Charles Abresch continued to run it, Andrew Hofherr , a cigar manufacturer, became Vice President, Harry P. Ellis became Chief Financial Officer and Secretary ; Abresch's cousin Louis Schneller Jr. was won as plant manager . The address for the plant is 392 to 398 Fourth Street and 407 to 415 Poplar Street; it was later changed to 1242, 1246, and 1254 North Fourth Streets.

The company held various patents, including a closed van with sliding doors for transporting crates . It became a mainstay of the company, which sold its vehicles across the United States and exported to Mexico . In 1892 Abresch invested US $ 35,000 in expanding the facility.

Plans for an automobile monopoly

Charles Abresch went public in the fall of 1889 with a plan to found a US $ 5 million company to control automobile manufacturing in the United States. This project failed because the funding did not come about. In 1895 the notorious Selden patent became legally effective, granting the owners a monopoly on road vehicles with internal combustion engines. After that, Abresch seems to have postponed his plans in this regard.

Charles Abresch Company, Inc. (1893-ca. 1945)

A name change to Charles Abresch Company, Incorporated took place in 1893, whereby it is unclear whether the entry in the commercial register was made at this time or existed earlier and was only added. It was capitalized at US $ 220,000 in 1894 and employed over 800 people. The company continued to exist in this legal form for the next few decades.

The following list of customers from 1895 shows how strongly Abresch was oriented towards brewery vehicles:

- Danville Beer & Ice Company, Danville, Illinois

- CL Centlivre Brewing Company, Fort Wayne, Indiana

- Indianapolis Brewing Company, Indianapolis (Indiana)

- Dubuque Malting Company, Dubuque, Iowa

- EC Peaslee, Dubuque, Iowa

- Koppitz-Melchers Brewing Company, Detroit (Michigan)

- A. Fitger, Duluth, Minnesota

- Excelsior Brewery, St. Paul, Minnesota

- GS Fanning, Auburn (New York)

- CA Koenig, Auburn (New York)

- Iroquois Brewing Company, Buffalo (New York)

- H. Zeltner Brewing Company, New York City

- Rochester Brewing Company, Rochester (New York)

- Ph. Liebinger Brewing Company, Brooklyn (New York)

- Crystal Spring Brewing Company, Syracuse (New York)

- Fitzgerald Brothers, Troy (New York)

- P. McGuinness, Utica (New York)

- Foss-Schneider Brewing Company, Cincinnati, Ohio

- L. Hosier Brewing Company, Columbus, Ohio

- M. Mason, Hamilton, Ohio .

- New Philadelphia Brewing Company, New Philadelphia, Ohio

- Jackson Koehler, Erie (Pennsylvania)

- Weisbrod & Hess, Philadelphia (Pennsylvania)

- Columbia Brewing Company, Shenandoah, Pennsylvania

- Galland-Burke Brewing Company, Spokane (Washington)

- S. Kappler, Vancouver , British Columbia , Canada

Abresch cars were delivered to Australia in 1891 .

On April 13, 1898, the plant, which had only been built six years earlier, was hit by a devastating fire, which fortunately did not claim any human lives. The fire broke out very quickly in the engine room of the building at 10 p.m. and was not extinguished by midnight. The extinguishing work was made more difficult by strong winds of up to 50 km / h. Most of the six-story brick building was in flames; 20 families in the neighborhood had to be evacuated. The event was reported in the national press. The damage to the Abresch Company was initially estimated at US $ 140,000, of which US $ 50,000 was due to building damage, US $ 30,000 to the destroyed machines and US $ 60,000 to the burned warehouse. A few days later, Charles Abresch was quoted with slightly lower figures. He estimated the damage to be around US $ 100,000, 80% of which was insured. 100 employees temporarily lost their jobs until a new building could be put into operation. This was erected immediately afterwards in the same place.

WF Davis

In the late 1890s there were several attempts by Abresch to gain a foothold in motor vehicle construction. They overlapped in time and an engineer named WF Davis appears to have played a role in all of them. This was an acknowledged expert on internal combustion engines and a co-founder of Davis Gasoline Engine Company in Waterloo ( Iowa produced), which mainly stationary and marine engines. The company was registered for the Chicago Times-Herald Contest in 1895 , but could not take part in this officially first car race in the USA because the vehicle was not ready in time.

After Davis left the company, he worked for the newly founded farm equipment manufacturer Jaimey Manufacturing Company in Ottumwa ( Wapello County , Iowa), 180 km south of Waterloo. There he tried to go into series production with an automobile he had designed, which apparently failed.

A mysterious runabout

Apparently, Davis approached Charles Abresch around 1898 in search of investors for his vehicle. The plan was for Abresch to produce a small runabout designed by Davis . No further information is available for this vehicle.

On September 9, 1899, the Milwaukee Journal reported in a preview of the Wisconsin State Fair , which took place in West Allis, Wisconsin in the second week of September , of a planned, now somewhat strange-looking double event. On the one hand, an automobile exhibition was to be held - with only 2,500 automobiles manufactured in the USA in 1899, it was an extraordinary event in itself. On the other hand, an Abresch car was supposed to compete in several races against the trotter King Allar on the racecourse in West Allis . The outcome of this first competition of its kind in Wisconsin is unknown, but the vehicle is interesting. The newspaper reported that it was only built at Abresch and tested in Chicago. It was built up to 30 mph (48 km / h) and except for the engines in Milwaukee.

The highwheeler

A little more is known about a highwheeler that Davis also designed for the Charles Abresch Company . This vehicle was significantly larger than the runabout and designed as a brake for 7 people. It had a Davis two-cylinder engine with water cooling and an output of 10 HP using an unknown measuring method. The power transmission took place with belts on the differential , which was attached to the countershaft . Gears at both ends of this shaft were connected to sprockets by means of drive chains , which in turn were firmly attached to each rear wheel. These rotated around a fixed axis . The vehicle weighed 2,300 lb. av. (approx. 1040 kg) and is said to have reached 12 mph (approx. 20 km / h). It appears that only one was built as a prototype . One source suggests that this highwheeler could have been built around 1895.

In April 1900, the Automobile Revue reported that the Charles Abresch Company was planning to start manufacturing heavy trucks and beer trucks and would later also produce passenger cars on the side. There was such a production in the episode, but it was minimal. In contrast, the construction of horse-drawn commercial vehicles continued to be very successful. Abresch supplied the US Army with horse ambulances, which were apparently stationed in Cuba during the Spanish-American War in 1898. Abresch exported his cars to Manila ( Philippines ), as the Milwaukee Journal noted on January 10, 1900. Abresch was awarded the contract for this government contract for eight different types of wagons against strong national competition; The decisive factor was the quality of the ambulances.

The lack of automobile revolution

In November 1899 Davis and Abresch made headlines again. The Milwaukee Journal reported abundantly on the 7th that Davis was preparing to start a business in Milwaukee. Generously endowed with a capital of US $ 1 million, motor vehicles were to be manufactured according to Davis designs. The sensationally presented article promised that Milwaukee would become the center of automobile manufacturing in the USA and was full of praise for the inventor, who had "removed all obstacles" that had hitherto "stood in the way of general use of the horseless carriage". The start of production at “one of the largest car manufacturers in the city” is imminent; the vehicle will be presented to the public in December.

Davis "invention" was a drive kit that could be retrofitted to any horse-drawn vehicle, making it an "automobile". According to the definition, it is about an avant train and therefore by no means a new invention. In the press at the time it was called the Automobile Motor . The said article in the Milwaukee Journal promised true miracles. She called a top speed of - hard to imagine - 50 mph (80 km / h) and expected that the drive unit could be produced so cheaply that it would have become "affordable for everyone". In addition, the paper made a very simple calculation: an automobile usually weighed 1,800 to 2,400 lb. av. (approx. 820 to 1090 kg), Davis invention, however, only 75 (34 kg). The weight of the carriage to be motorized was not taken into account. Typically, such a retrofitting of a carriage consisted of exchanging the turntable and drawbar for another one that contained the axle, front wheels, the engine, the power transmission and the steering. Such a vehicle inevitably became heavier, not lighter, as a result of the conversion.

Just a day later, Davis' hometown newspaper took up the subject, the Waterloo Daily Courier . The visibly euphoric newspaper wrote on November 8th that Davis had founded a public company worth one million dollars in Milwaukee to manufacture and market a motor vehicle. This invention is the best of its kind that has ever been presented to the public. Davis accepted an "entrepreneurial" man's invitation to Milwaukee. Apparently Charles Abresch was meant.

These reports are almost an example of one of the reasons why the young automotive industry in the USA was received with skepticism. The announced events did not materialize and most of the information proved to be inaccurate. As we have seen, Avant-Trains were neither new nor promising. They were by no means cheap and a conversion was only worthwhile for high-priced vehicles. Its main disadvantage, however, was inadequate steering. There is no evidence of a greater influence on the development of passenger cars, and they disappeared as soon as the number of carriages and wagons that could be converted was reduced.

For WF Davis, the collaboration with Abresch probably ended shortly afterwards. The Abresch-Cramer truck built by Abresch 1910–1912 was created without his support. There is no known association with the engine manufacturer Davis Manufacturing Company in Milwaukee. This company was led by Frank Davis and manufactured the Cyclecar Vixen from 1914 to 1916 . Although various American manufacturers have produced vehicles with the Davis brand name , I do not associate any with WF Davis and none were based in Milwaukee.

Setbacks

In April 1900 a labor dispute broke out between the National Carriage Maker's Association (NCMA) and an unidentified union . This tried to enforce a ten percent wage increase. Several NCMA-affiliated companies with a total of 285 workers were affected, 85 of them at Abresch . Were on strike Theodore Habhegger Company , John Miller & Son , Stehling & Blommer Company , Joseph Heinl & Sons , Stumpf & Company , John Knoll Company and John Knapp Company . In Abresch it came to lockout the workforce after plant manager Louis Fast from the planned out walk and strike had learned. Schneller told the press that his company practically consistently paid wages that were above the minimum wage. Accordingly, a blacksmith at Abresch earned up to US $ 2.60 a day and a Wagner US $ 2.25. The minimum wage was US $ 1.75. At that time there were five forging furnaces in operation in the company. 20 employees worked in painting alone.

In the early morning of December 31, 1902, the company was again hit by a massive fire; in turn, the entire system was destroyed. The Oshkosh Daily Northwestern printed a report from the Associated Press that same day . According to this, the fire broke out in the repair shop in the back of the building and had spread so quickly that the fire brigade could not save a single car. Seven firefighters were injured during the fire fighting when a wall collapsed above them. The property damage amounted to US $ 100,000 and was partly covered by insurance.

The fire risk was high in many industrial companies at that time. With their wood, paint, upholstery and delivery warehouses and the attached forging ovens and boilers for the machines, which are often powered by steam, the manufacturers of wagons were particularly at risk.

New building

A new building was already in operation in October 1903 and was presented in the industry magazine National Bottlers Gazette . Accordingly, it was a four-story brick building with a stone foundation on a floor plan of 100 × 150 feet (approx. 30 × 46 meters). It was electrically lit and heated with a hot air blower. The delivery warehouse for the completed wagons on the ground floor had a cement floor. On the first floor were the building services, the wheel building with electric welding systems and hydraulic presses as well as cutting and punching machines and 15 forging furnaces, which were apparently already in full operation again.

The car and body shop was set up on the second floor. Their production apparently took place side by side; the division of space into a machine room on the south side and 24 workplaces on the north side suggests this at least. The third floor was reserved for the paint shop and painting. According to the report, the company attached particular importance to high-quality paints and varnishes and careful execution by trained specialists.

The article shows that Charles Abresch was President of the company and that Vetter Louis Schneller was in charge of business and plant management.

Body shop for passenger cars

Automobile and commercial vehicle bodies were introduced to the Charles Abresch Company around the turn of the century. The area developed from occasional one-offs to series production for smaller vehicle manufacturers. Series production from 1903 is documented. In the description of the new factory building already mentioned, the National Bottlers Gazette mentions that Abresch received orders for automobile bodies every day; some orders were for up to 500 units. In 1903, 11,235 automobiles were made in the United States. Small series for passenger car manufacturers can be proven for Fawick / Silent Sioux , Ford , Great Western , Kissel and Mitchell .

For Silent Sioux and its successor, Fawick Flyer , Abresch produced Touring bodies using a method developed by Thomas L. Fawick , in which aluminum sheet was attached to a wooden structure. Abresch was one of the first companies to use this construction method, which later became common. The process was time-consuming and required a great deal of specialist knowledge.

Special bodies were manufactured on request until the 1930s.

Kissel representation

In 1908 Abresch took over the representation of Kissel vehicles in Milwaukee. It should have been interesting for the company that this then respected manufacturer of mid-range and upper-class automobiles also produced commercial vehicles. With the sale of chassis and superstructures from a single source, the Charles Abresch Company was able to use its business contacts even more profitably.

In November 1914, the Automobile Trade Journal reported that the Greek government had ordered 50 Kissel chassis with Abresch ambulance superstructures.

Body construction for commercial vehicles

The body department was expanded at about the same time as the car bodies were added at the turn of the century. This business grew rapidly as customers increasingly switched from carts to motor vehicles. This is also the reason for starting our own commercial vehicle production, described below. These were geared towards the needs of the existing clientele. It is therefore not surprising that increasingly standardized superstructures for breweries and bottlers were to be found among them; Most of the company's own trucks were also bodied. Carriages remained on offer for a while, but by 1920 they probably no longer played a role

Abresch commercial vehicle bodies can be found next to the Abresch resp. Abresch-Cramer also on chassis from Atterbury , Diamond T , FWD , Kissel, Sterling and White . Abresch was also a concessionaire for Hercules bodies for light commercial vehicles. These superstructures were delivered as CKD kits and assembled at Abresch . This expanded the company's own program for heavy trucks downwards. Such bodies were popular and were offered by various regional manufacturers and often in cooperation with Ford branches.

Kissel beer truck with Abresch body for Chester Beer in Chester, Pennsylvania (1912).

1918 White beer truck with Abresch body for the Primator Brewery in Garden City (1918).

More labor disputes

The introduction of a wage system based on the number of items processed led to a strike in the paint shop in September 1910. It appears that the strike led to the creation of the Carpenters' Local 1053 of the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America . The strikers demanded a nine-hour day and employment at the previous wages of 24¾, 27½, 30 and 32½ cents per hour.

The Milwaukee Sentinel reported on June 8, 1911 about another work stoppage, which the workforce was able to resolve after just three hours.

The longest and most difficult labor dispute at Abresch broke out when the management decided on March 1, 1916 not to extend the current agreement with the unions on a closed shop employment policy and thus also to employ non-unionized workers. The company went on strike for over three months. More than 200 car and body builders were involved. The industrial action attracted national attention, and Motor Age magazine reported on June 8, 1916 that the strike had been brokered and that work had resumed. Abresch prevailed with the desired, open employment policy.

Commercial vehicle manufacturing

In 1909 the company started its own commercial vehicle production. The construction was provided by Robert Kremers , who called himself Cramer . He was a Milwaukee engineer who had studied in Europe and previously worked for Allis-Chalmers . At the time, Charles Abresch was President and Chief Financial Officer of the company, Cousin Louis Schneller was Vice President and General Manager and Edmund Paul was Secretary. Production began in 1909 and was soon relocated to a new subsidiary.

technology

These vehicles were identical to the corresponding models from Abresch-Cramer. There were three technically very similar series with payloads from 1 to 4 shillings. tn. (900 to 3600 kg). A five-tonne truck is mentioned, but does not seem to have been built.

- Abresch-Cramer Model A with 3.6 liter displacement; Payload 1.0 to 1.5 sh. tn.

- Abresch-Cramer Model B with 6.4 liter displacement; Payload 2.0 to 3.0 resp. 4.0 sh. tn.

- Abresch-Cramer Model C with 7.7 liter displacement; Payload 3.0 to 4.0 sh. tn .; at least this model was also available as a forward control .

These commercial vehicles were bulky, water-cooled four-cylinder - four-stroke engines with T-head - valve control .

Power was transmitted by means of a three-speed gearbox and shaft drive to the countershaft in front of the rear axle. The rear wheels were driven by chains from the countershaft .

Abresch-Cramer Auto Truck Company (1910–1912)

The Abresch-Cramer Auto Truck Company was organized as a corporation in early 1910 . The company was a subsidiary of the Charles Abresch Company and was founded to manufacture the Abresch-Cramer trucks. It was financed with US $ 20,000. The board of directors included Charles Abresch, Robert Crawley and Louis Schneller . "Robert Crawley" seems to be a misspelling of "Robert Cramer", who was also documented as managing director. Shortly thereafter, the company moved to the Stehling building on Third and Poplar Streets in Milwaukee. It was only a few blocks away from the motherhouse.

The vehicles corresponded to the types previously manufactured in the parent company. The annual production was designed for 100 vehicles and should soon be doubled. Cramer had the ambition to become one of the largest commercial vehicle manufacturers in the USA, but these plans could not be realized. Shortly after the death of Charles Abresch in 1912, his successor Louis Schneller gave up commercial vehicle production entirely and concentrated on body construction.

prohibition

The Prohibition in the United States was introduced 1919th For Abresch, with his customer base consisting largely of breweries, distilleries and bottlers, it had a serious impact. Many small breweries disappeared from the market. The bigger ones like Blatz , Miller , Pabst or Schlitz switched to other markets and produced near beer , soda , malt syrup , beer or extract , fruit juices , ice cream , yeast or cheese. Louis Schneller downsized the company. Part of the lost commercial vehicle business was compensated for by occasional special bodies for passenger cars. A patent from 1924 for a foldable device that turned a roadster or coupé into a pickup truck does not seem to have held its own. The device could be folded up in the trunk when not in use.

As early as 1929, Abresch advertised repairs and improvements to automobiles, but especially with repainting with the new, "weatherproof" DuPont Duco paints.

Prohibition in Wisconsin was relaxed in 1926. The legislative initiative with which it was abolished nationwide in December 1934 also came from this state.

Motorcycle sidecar

The diversification into the construction of delivery van bodies for trikes and especially in motorcycle sidecars proved to be promising for the future . Customers included the Goulding Manufacturing Company and, from around 1923, primarily Harley-Davidson . In 1936 Abresch brought out an all-steel sidecar for Harley-Davidson and from 1942 supplemented it with a medium-sized cargo box , also made of metal, for transporting goods. It replaced the two boxes previously manufactured by Harley-Davidson. This business relationship only ended when the motorcycle manufacturer started producing its own sidecars made of GRP in the former Tomahawk boat yard in 1966 .

Abresch survived the difficult years of the Great Depression by downsizing. Mainly vehicles were now repaired.

Bennett Coachworks

After the Second World War , the company was renamed Auto Body Ltd. reorganized. It remained in this form until 1965. After losing the sidecar contract with Harley-Davidson, it changed hands several times and has been known as Bennett Coachworks since 1980 . The company specializes in the construction of hot rods and the restoration of classic automobiles.

Remarks

- ↑ The source names Louis Schneller Jr. but he was only ten years old at the time and joined the company in 1889 at the earliest.

- ↑ It is obviously not about the Swiss Automobile Review, founded in 1906

-

↑ Excerpt from the report in the Milwaukee Journal of November 7, 1899 in the wording:

“Within the month it will be known in the land that the erstwhile modern automobile has brought Milwaukee again to the fore, for this city is soon to be the center of the automobile industry in the United States. “Some three weeks ago there came to this city a man from Iowa whose fertile brain had overcome the obstacles which have heretofore hindered the general use of the horseless carriage and at present one of the largest wagon concerns in the city is busy getting out the first machine, which will be put on exhibition some time in December. “The automobiles now in use weigh 1,800 to 2,400 pounds, while the invention of the Iowa man, WF Davis, weighs only 75 pounds and can be attached to any vehicle now drawn by a horse. More than that, it is capable of reaching a speed of fifty miles an hour, and its cost will be so small that it will be within the reach of everybody. -

↑ Excerpt from the report in the Waterloo Daily Courier dated November 8, 1899 in the wording:

“CAPITAL TO BE $ 1,000,000. “Owing to its extreme lightness, the cost of propulsion will also be greatly reduced, and the fact that a stock company backed by $ 1,000,000 is soon to be formed in this city to manufacture the new machine and put it on the market indicates that it is all the inventory claims for it. "WF Davis, formerly vice president of the Davis Gasoline Engine company of Waterloo, Ia .; Inventor of the new auto, is very well known among machine men as the inventor of the Davis gasoline engine. Some nine months ago he sold out his interests in the Davis company and devoted his time to the perfection of the new machine, which has now been finished. Capitalists in Kansas City made him flattering offers to locate there to manufacture his new invention, but through the influence of JA Warnken, of Milwaukee who was employed by the company as a traveling salesman, he was induced to locate here. “ABRESCH COMPANY INTERESTED“ The Charles Abresch company, wagon manufacturers, of 398 Fourth street, became interested in the plan and have since come into possession of the right to manufacture the new vehicles, paying a considerable sum and a royalty besides. “For three weeks Mr. Davis has been busy at the Abresch plant building the first machine, and within a month a public exhibition will be given at which makers of automobiles all over the world will be challenged to compete. “CAPITALISTS ARE INTERESTED“ Although the plans of the inventor and the Abresch company have been carefully kept from the public, several prominent Milwaukee capitalists have been approached with a view to forming a corporation for the exclusive manufacture of the motor, and the matter has so far progressed that backing to the amount of $ 1,000,000 is said to be in sight. The name of the man who will be at the head of the new corporation is known to The Journal, but cannot be made public at this time. However, he is so well known throughout the United States that his name in connection with the new manufacturing enterprise insures us stability at the outset. “Mr. Davis has moved to this city with his family and will remain to take charge of the manufacture of his invention. “A REVOLUTION PROMISED. “The horseless carriages now in use are cumbersome affairs at best, and it is declared that the neat, light and speedy invention of the Milwaukee man will of a certainty revolutionize their manufacture and mark Milwaukee as the center of one of the greatest improvements of modern times. "

literature

- George Nick Georgano (Ed.), G. Marshall Naul: Complete Encyclopedia of Commercial Vehicles. MBI Motor Books International, Osceola WI 1979, ISBN 0-87341-024-6 .

- Albert Mroz: Illustrated Encyclopedia of American Trucks and Commercial Vehicles. Krause Publications, Iola WI 1996, ISBN 0-87341-368-7 .

- Beverly Rae Kimes (Ed.), Henry Austin Clark Jr.: Standard Catalog of American Cars 1805-1942. 3. Edition. Krause Publications, Iola WI 1996, ISBN 0-87341-428-4 .

- Association of Licensed Automobile Manufacturers (Ed.): Handbook of Gasoline Automobiles / 1904–1905–1906. Introduction by Clarence P. Hornung. Dover Publications, New York 1969.

- National Automobile Chamber of Commerce : Handbook of Automobiles 1915–1916. Dover Publications, 1970.

- Consolidated Illustrating Company: Milwaukee: A Half Century's Progress, 1846–1896: A Review Of The Cream City's Wonderful Growth And Development From Incorporation Until The Present Time. 1896. (Reprint: Nabu Press, 2011, ISBN 978-1-178-49035-0 )

Web links

- Mark Theobald in Coachbuilt.com: Charles Abresch Co. (accessed August 16, 2017)

- Bennett Coachworks, website. (accessed August 16, 2017)

- Wisconsin State Fair Park: History Of the Wisconsin State Fair ; Website, memento. ( Memento of April 6, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (accessed on August 9, 2017)

- csgnetwork.com: cubic inch calculator (accessed August 16, 2017)

- findagrave.com: Louis Schneller (1874–1939). (accessed August 13, 2017)

- findagrave.com: Wilhelmine "Minnie" Eissfeldt Schneller (1872–1959). (accessed August 13, 2017)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Georgano, Naul: Complete Encyclopedia of Commercial Vehicles. 1979, p. 22 (Abresch-Kremers)

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Coachbuilt: Charles Abresch Co.

- ↑ a b c d e f Milwaukee Journal, April 28, 1912; quoted in: Coachbuilt: Charles Abresch Co.

- ↑ a b c Commercial Vehicle, May 1912; quoted in: Coachbuilt: Charles Abresch Co.

- ↑ a b Milwaukee Sentinel, September 9, 1939; quoted in: Coachbuilt: Charles Abresch Co.

- ↑ findagrave.com: Louis Schneller (1874–1939).

- ↑ Consolidated Illustrating Company: Milwaukee: A Half Century's Progress, 1846-1896. 1896/2011.

- ↑ a b c d e National Bottler's Gazette, October 5, 1903; quoted in: Coachbuilt: Charles Abresch Co.

- ↑ a b Wisconsin State Journal, September 8, 1939; quoted in: Coachbuilt: Charles Abresch Co.

- ↑ findagrave.com: Wilhelmine Eissfeldt Schneller (1872–1959).

- ↑ a b Milwaukee Weekly Wisconsin, April 16, 1898; quoted in: Coachbuilt: Charles Abresch Co.

- ↑ a b Fort Wayne News, 14 April 1898; quoted in: Coachbuilt: Charles Abresch Co.

- ↑ a b Waterloo Daily Courier, November 8, 1899; quoted in: Coachbuilt: Charles Abresch Co.

- ^ Wisconsin State Fair Park: History Of the Wisconsin State Fair.

- ↑ a b Merkert: Passenger cars, buses and trucks in the United States. 1930, p. 14 (Table 7).

- ↑ Milwaukee Journal, September 9, 1899; quoted in: Coachbuilt: Charles Abresch Co.

- ↑ a b c d e f Clark Kimes: Standard Catalog of American Cars 1805-1942. 1996, p. 13 (Abresch)

- ↑ Milwaukee Journal, January 10, 1900; quoted in: Coachbuilt: Charles Abresch Co.

- ↑ Milwaukee Journal, November 7, 1899; quoted in: Coachbuilt: Charles Abresch Co.

- ^ Clark Kimes: Standard Catalog of American Cars 1805-1942. 1996, p. 417 (Davis)

- ^ Clark Kimes: Standard Catalog of American Cars 1805-1942. 1996, pp. 1503-1504 (Vixen)

- ^ Clark Kimes: Standard Catalog of American Cars 1805-1942. 1996, p. 1611 (Wisconsin automaker)

- ↑ Milwaukee Journal, April 11, 1900; quoted in: Coachbuilt: Charles Abresch Co.

- ^ Oshkosh Daily Northwestern, December 31, 1902; quoted in: Coachbuilt: Charles Abresch Co.

- ^ Automobile Trade Journal, November 1, 1914, cited in: Coachbuilt: Charles Abresch Co.

- ↑ Milwaukee Journal, September 28, 1910; quoted in: Coachbuilt: Charles Abresch Co.

- ↑ Milwaukee Sentinel, June 8, 1911; quoted in: Coachbuilt: Charles Abresch Co.

- ^ Automobile Trade Journal, June 8, 1916; quoted in: Coachbuilt: Charles Abresch Co.

- ↑ a b c d Commercial Vehicle, August 1910; quoted in: Coachbuilt: Charles Abresch Co.

- ↑ a b c Abresch-Cramer: Abresch Gasoline Commercial Cars. Advert, circa 1909

- ^ A b Charles Abresch Co: Abresch Model C 3-ton Truck in use for Jung brewery, Milwaukee. Advert, 1911.

- ^ Bennett Coachworks, website.